Yves here. People are skilled at making themselves and others miserable and now at wrecking the planet. We do get some of what we consider good art, but is it worth it? E.O. Wilson attributed a lot of human planetary destructiveness to our being meat-eating primates. But could our intellects be the real problem?

Where we are may illustrate Dollo’s Theory of Evolution. This is made up, a device at the start of a novel that I barely got into as a house guest, and I don’t recall the name of the book or the author. Nevertheless, Dollo posited that species developed characteristics that gave them competitive advantage. So far, so goo.

But Dollo went further and claimed species continued to develop those qualities beyond the point of maximum advantage. Saber-toothed tigers had massive teeth and jaws that enabled them to kill prey like mastadons. But when they died out due to their predation and other factors, their dental equipment was ill adapted to smaller prey, so they went hungry. Dinosaurs got so big that pretty much nothing could kill them. But they also outgrew their ability to manage their bulk. They developed second brains in their stomachs to cope and died of anatomical schizophrenia.

By Rachel Nuwer, a science journalist whose writing has appeared in The New York Times, National Geographic, Scientific American, BBC Future, and elsewhere. She is the author of “Poached: Inside the Dark World of Wildlife Trafficking.” Originally published at Undark

The German philosopher Friedrich Wilhelm Nietzsche was, by all accounts, a miserable human being. He famously sought meaning through suffering, which he experienced in ample amounts throughout his life. Nietzsche struggled with depression, suicidal ideation, and hallucinations, and when he was 44 — around the height of his philosophical output — he suffered a nervous breakdown. He was committed to a mental hospital and never recovered.

Although Nietzsche himself hated fascism and anti-Semitism, his right-wing sister reframed her brother’s philosophy after his death in 1900 as a rationale for subjugation of people that the fascists saw as weak, contributing to the moral bedrock of the Nazi Party and justification for the Holocaust.

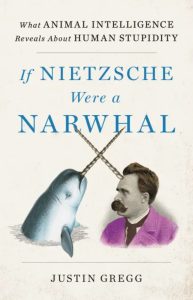

BOOK REVIEW — “If Nietzsche Were a Narwhal: What Animal Intelligence Reveals About Human Stupidity,” by Justin Gregg (Little, Brown; 320 pages). Visual: Hatchette Book Group

Would Nietzsche have been happier — and would the world overall have been a better place — had the philosopher been born some other species other than human? On its face, it sounds like an absurd question. But in “If Nietzsche Were a Narwhal: What Animal Intelligence Reveals About Human Stupidity,” scientist Justin Gregg convincingly argues that the answer is yes — and not only for Nietzsche, but for all of us. “Human cognition and animal cognition are not all that different, but where human cognition is more complex, it does not always produce a better outcome,” Gregg writes. Animals are doing just fine without it, and, as the book jacket says, “miraculously, their success arrives without the added baggage of destroying themselves and the planet in the process.”

Gregg — who holds a doctorate from Trinity College Dublin’s School of Psychology, teaches at St. Francis Xavier University, and has conducted research on dolphin social cognition — acknowledges that human history is marked by incredible breakthroughs that hinge on our intelligence. Yet, nonhuman animals do not need human-level intelligence to survive and be evolutionary successful, as Gregg points out, which is why this trait isn’t more prevalent across species.

He builds his often hilarious, sometimes unsettling, case against human superiority across seven chapters. Each one deals with a unique aspect of our psyches — from our capacity to conceive of our own mortality to our ability to communicate about “a limitless array of subject matter” — and provides ample evidence showing that not only are these mental attributes unnecessary for survival, they’re oftentimes more a liability than a gift.

Our species stands out first and foremost, Gregg begins, for our tendency to ask “Why?” “Of all the things that fall under the glittery umbrella of human intelligence, our understanding of cause and effect is the source from which everything else springs,” Gregg writes. “Why” questions arguably spurred innovations such as agriculture (“What causes seeds to germinate?”), fields of study such as astronomy (“Why is that star always in the same place each spring?”) and the advent of religion and philosophy (“Why am I here? And why do I have to die?”).

Asking “why,” however, is not necessary for success on either an individual or evolutionary scale, Gregg writes. Other species presumably flourish without it, and many have arrived at similar life hacks as humans, but without seeking a deep understanding of causation. Chimpanzees, birds, and elephants know how to self-medicate with plants, clay, and bark, for example. They do not need to know why these remedies work, Gregg writes, only that they do.

For all the good asking “why?” has done us, Gregg argues, it has also had negative repercussions, by justifying biases such as racism (“Why do humans from different parts of the world look different?”) and, as he writes, by leading us to create technologies that can threaten to destroy us — internal combustion engines, for example. The solution to climate change and other existential threats that we’ve created for ourselves, Gregg points out, will come from the same why-based system of thought that brought about these problems in the first place. However, “it is an open question whether a solution will arrive in time, or if our why specialist nature has doomed us all,” he writes.

Our obsession with morals — “not just that we should behave a certain way, but why we should,” as Gregg puts it — has also generated untold amounts of suffering. Norms that dictate how one should and should not behave within one’s social world exist throughout the animal kingdom. Chickens have pecking orders, for example, but they do not ruminate on whether that system is fair or just, Gregg points out. On the other hand, some species do have sensitivity to social inequity. In one famous experiment, scientists offered Lance and Winter, two capuchin monkeys in side-by-side cages, different rewards for completing the same task. Winter received a grape (a preferred treat), and Lance received a slice of cucumber. As Gregg recounts it, when Lance saw Winter repeatedly receive a grape for the task, she violently threw the cucumber back at the researchers and banged on her cage. “This is evidence that Lance felt as if it was unfair that she was given the lesser food reward for the same task,” Gregg writes. “Lance was responding to the violation of a fairness norm.”

But humans take such social norms to an extreme, Gregg argues. We attempt to enforce universal standards for “right” and “wrong” and spin up elaborate justifications, monitoring systems, and punishments to ensure that others follow those made-up rules. A major problem with morals, however, is that they are subjective and can easily lead to justification for one demographic or cultural group’s oppression of another. From 1883 to 1996, Gregg writes, 150,000 First Nations children in Canada were forcibly removed from their homes and sent to residential schools, where they were subjected to abuse, trauma, cultural genocide and even death. The prime minister under which the atrocities began viewed forced assimilation as a “moral imperative, the best solution for bringing Indigenous children in line with modern Western values,” Gregg writes.

Moral grounds have been used to condone the persecution of minority groups; rationalize genocide; and to advocate for eradication of entire cities, including by dropping nuclear bombs: “The history of our species is the story of the moral justification of violent acts resulting in the pain, suffering, and deaths for billions of our fellow humans who fall into the category of ‘other.’” This stands in contrast to every other species, Gregg continues, which lack “the cognitive capacity to systematically kill entire subgroups of their same-species populations resulting from a formal claim to moral authority.”

Humans, therefore, might be succeeding not because of, but in spite of, our moral aptitude, he writes, having taken the social norms that govern and constrain social behavior in most species to self-destructive lengths.

But the most damning chapter of the book — and my favorite — concerns a special brand of cognitive dissonance Gregg calls prognostic myopia, or “the human capacity to think about and alter the future coupled with an inability to actually care all that much about what happens in the future.” This happens on an individual level all the time. Prognostic myopia is at play, for example, when you decide to stay up late drinking with friends, knowing you have to be up early the next morning. The consequences of that decision only fully hit the next morning, when the alarm goes off and the hangover begins. This is because our brains, like those of other animals, are wired to deal primarily with the here and now.

The real problem, however, is that unlike other species, “our decisions can generate technologies that will have harmful impacts on the world for generations to come,” Gregg writes. Spread across billions of people and coupled with modern technologies, our tendency to live in the moment today is condemning future generations and the world at large to increasingly dire prospects with each passing year. According to the Global Challenges Foundation, as of 2016, there was a 9.5 percent chancethat humans will go extinct within the next 100 years. And even if we do survive, we’re looking at a potential warming of 2.7 degrees Celsius by 2100, on a scale that “will render most of the planet uninhabitable,” Gregg maintains. Yet we seem to lack the political will to stop this from happening, he adds, because “the further into the future we go, the less we care.”

As Gregg points out, “It is the greatest of paradoxes that we should have an exceptional mind that seems hell-bent on destroying itself.”

Yet evolutionarily speaking, our slide toward extinction isn’t outside the norm. Countless species have come and gone since life began on the planet some 3.7 billion years ago. As Gregg writes, “Our many intellectual accomplishments are currently on track to produce our own extinction, which is exactly how evolution gets rid of adaptations that suck.”

Top review.

I am tempted to buy the book.

Thank you for sharing the it.

Well done!

As I see it, the problem is not so much in the asking why? as in answering the question by, as Yves would put it, making sh!t up. Words are good for that. Ask any salesman.

We very much underestimate other creatures.

But these types of essays/books also seem to underestimate humans.

If you work in construction, you see a very normal group of people, of no particularly great intelligence build some pretty crazy stuff. With supplies coming from factories also manned by some very normal people, and transported by very normal people using personal specialized experience and recorded collective wisdom of how to do it.

It is kind of like an ant colony squared – but ants are pretty amazing.

Yeah, ordinary human animals can do “pretty crazy stuff” by “using personal experience and collective wisdom,” just like all other sorts of animals. But..But..But unlike the other sorts the “stuff” they do tends to lead them rather irresistably to destroy each other and a great deal more besides. They are, you see, “not just animals.” They are, as some great helmsman or other might put it, “Animals With Human Characteristics.”

You hit the nail on the head when you wrote “crazy stuff”. Crazy stuff like automobiles, and nuclear weapons, and toxic chemicals.

“Normal people” may have built those things, but the plans and knowledge of how to build that stuff were probably made by a person of above average intelligence. Engineers, architects etc.

from Wikipedia:

If evolution were not reversible, hereditary blindness would not have been a successful adaptation for fish living in perpetually dark caves.

Evolution has no direction whatsoever; so the question of “reversability” is meaningless. Of course, adaptation possibilities are limited by physical and biochemical constraints, some of which are influenced by the genomic histories of previous evolution. But adaptation to new circumstances (such as cave dwelling) are stochastic, and may or may not show up as “reversals” of genomic changes.

I would think Evolution would be subject to entropy, which would give it a certain direction, so to speak.

Mixing evolution and entropy in the same sentence is risky without a whole lot of background context, kind of like, I dunno, taking lessons from the subprime meltdown and applying them to the Covid pandemic. Useful ideas in very separate contexts. In particular, entropy is an observed property of closed systems. Evolution occurs in an open system (the sun is shining – unless you zoom out to cosmology, in which case talking about biological evolution quickly turns into science fiction.) To your point – evolution has been described as a local reversal of entropy.

It is common to say that “Evolution has no direction whatsoever…” but there is a flaw in this thinking, and that is complexity. The first organisms were simple, latter ones increasingly complex. Human consciousness should be considered as a step in complexity, a profound step in that direction. The ultimate results of that step have yet to be seen. Maybe a New Cambrian period defined by a blossoming of AI coinciding with the sunset of biological evolution towards “intelligence” and higher levels of biological consciousness? After all, given the inherent imperatives of biological evolution, can any biological organism be truly sustainable for any significant length of time, specially highly complex organisms? Maybe AI was the “ultimate goal” after all. (Not in reality, but in the same fashion that we humans think that we were the ultimate goal.)

If evolution is not reversible, then human beings will not be capable of returning to an earlier period of existence; that is, they may not be able to live as we did in the 1920s which, I think, would be one way to deal with and maybe change the climate from its destructiveness. Human beings will realize that no matter what they do to prevent climate change, it won’t happen because we ourselves aren’t able to change to a former existence.

Oh, I looked years back and found nothing when I searched for Dollo + evolution. Thanks!

This feels like the noble savage trope applied to animals, and it seems weird from someone who’s done dolphin research since it’s pretty well known that dolphins are raging assholes amongst themselves. What with the gang raping and sexual slavery to gangs of male dolphins. Chimps are just as bad and of course probably more comparable to us. It’s just that gangs of chimps going monkey hunting for fun and then skinning the captured monkey alive doesn’t make it into the popular primatology programs on National Geographic.

In the end the thesis that humans are pretty terrible is both true and supportable, I’m just not sure this is the appropriate way to support it since our problem is that we tend to take behaviors that are fairly common in the animal kingdom and scale them up.

David Graeber and David Wengrow’s The Dawn of Everything has an interesting angle on the origin of the “noble savage” trope in the 1600-1700s, when it was a hot topic,

“The men, they [early French observers in America] noted, were primarily occupied in hunting and, occasionally, war, which meant they could in a sense be considered natural aristocrats. The idea of the ‘noble savage’ can be traced back to such estimations. Originally, it didn’t refer to nobility of character but simply to the fact that the Indian men concerned themselves with hunting and fighting, which back at home were largely the business of noblemen.”

So more like ‘savage nobles’ rather than ‘noble savages’. They’re still backwards barbarians, but they get to live like nobility.

Don’t other social species war with each other over territory and dominance? True it’s instinctive rather than “congnitive” but perhaps that’s true in our case as well. Indeed some of us would contend the problem is not that humans think too much but rather don’t think nearly enough. When we do get attempts at social “science” as in economics it’s just as likely to be a rationalization for the instinctive dominance of one subgroup or another (i.e. capitalists).

One could also argue that the article is nibbling around what this whole blog is about: socialism–the virtues of sharing and cooperation–versus American style capitalism which depends on our “human nature” of competition and dominance to theoretically produce better survival chances for all. The problem with the socialists is that they think an appeal to reason is all that is needed and try to wish away that other part of us that is so powerful. There may indeed be no way to reconcile this other than “events.”

I would say Mr. Gregg doesn’t live by his own arguments. He seems to be very moralistic in making judgments of humans. He seems to ask why we make messes. So apparently he doesn’t take his own conclusions very seriously. Also, why does he think animal lives are so wonderful? Most animals die before maturity, in most species overwhelmingly so. (E.g., birds have two or three broods a season. They have to have so many offspring because most die. Lions are a pretty high up species; about one in eight male cubs lives to adulthood. Right now, young moose in a lot of parts of the east are infested with thousands of ticks, and really dying a lot, miserably.) Darwin often got depressed because animals’ lives are so miserable. What is it animals do that is so great, then? And well actually, according to Gregg, making moral judgments about the quality of animals’ lives is another of our mistakes. Gregg in other words spends a lot of time doing what he says we shouldn’t do (think, evaluate, as why), he adopts a moral criterion for what makes a species worthwhile (survival as a species), which is more of what we ‘re not supposed to do, and does not, I believe think seriously about the quality of animal lives, unlike, say, Darwin. I have a lot of worries about our species, too, but I don’t think that deciding we’re a waste of time is a particularly good solution, especially if one doesn’t even act according to one’s solution.

Also, why does he think animal lives are so wonderful? Most animals die before maturity …Right now, young moose in a lot of parts of the east are infested with thousands of ticks, and really dying a lot, miserably. Darwin often got depressed because animals’ lives are so miserable. What is it animals do that is so great, then

Werner Herzog couldn’t make it, I guess.

What I can say in response to you is in North America, before humans arrived, the continent was resplendent with a wide variety of flora and fauna. It seems they fared pretty well on their own. They weren’t miserable and dying off in large numbers. This is most likely true in every part of the planet, sea, land, and air. Humans came along and screwed up everything.

While it’s true that humans have poisoned the world, just because some species are successful in propagating themselves it doesn’t automatically follow that their lives are “good” or free of stress. Ecological balance isn’t good or bad, it just is. Nature can be cruel — animals are torn apart by predators, the big fish eat the little ones, etc.

Of course. Morals are more of a metaphor for attitudes that help us survive as a group–scientifically speaking of course. And if one is going to be scientific humans are just as much a part of nature as the elephants or the polar bears. We have screwed up the environment but I think many are too quick to assign villainy. As we are seeing with the current energy crisis turning such a massive system–once thought virtuous–in a different direction is not so easy in only a few decades.

I’m not so sure about that: mass extinctions we’re plentiful long before humans. I’d often wondered if the future paleontologists will think if the mass extinction that ended of mammals could possibly have been caused by mammals themselves.

As Lambert might say, “we” and “our” do a lot of work in this argument’s lazy nihilism. The distance between “we are doomed” and “we have doomed ourselves” is one littered with usurpation of power, exploitation of the many by the few, and so many other historical contingencies that this author (as interpreted by the reviewer, at least) seems content to ignore.

As mentioned above, Davids Graeber and Wengrow offer a far more honest and useful historical analysis in their _The Dawn of Everything_. Instead of feckless resignation, how about “we” use all of “our” capacities to take power from the ghouls running everything into ruin?

Perhaps you are over-analyzing a bit. The author didn’t put forth a grand theory. He merely makes the point that in simple terms goes like this: Humans may be too smart for their own good. Or, humans are too smart for their own good.

And what if we all are the ghouls and thinking that we personally are not is the “downside of exceptionalism”? One aspect of the Humans=nature argument is that, as with the creatures around us, our behavior is often all too predictable.

Christianity has some good ethical precepts one of which–not often lived up to in practice–is that “all are sinners” in need of redemption. Such redemption may not consist of a dunk in the baptismal pool but a good look in the mirror is always useful.

Reading this review I can’t help but be reminded of the novel “Blindsight” by Peter Watts. In short, aliens enter the solar system and uses its ability to imitate intelligence to prey on humans. Highly recommend it.

Gregg is right to point out that intelligence is not the pinnacle of evolution it is often billed to be. But at the same time, Michael’s comment is spot on – less intelligent animals aren’t exactly living in paradise either. Regardless, I think there’s a bigger insight Gregg’s framing sort of acknowledges but falls a little short on.

Evolution is often misconstrued as a process that is progressive in the sense that weaknesses are weeded out so that increasingly “strong” specimens emerge over time. In reality, evolution does an excellent job of selecting organisms suited for a particular niche. Niches, however, are extended both in space and time, thus the giant fangs of the sabre tooth tiger may have given it a huge advantage when the mammoths were around, but soon came to cost the species once its prey ceased to exist. Of course, organisms can change their niche as well. Human intelligence is particularly well suited for adapting a particular niche to human beings. While advantageous in some respects, it also seems to blow up in our face quite a bit.

Anyways, back to Gregg’s book. It seems like its doing good by challenging the “progress is always good” myth that seems so ingrained in our society (Pinker, looking at you). But the aside on morality seems off – though genocides are sometimes conducted in the name or morality, we shouldn’t lose track of the fact that many humans will see through these lies and recognize the horror of the genocide in part due to their own moral reasoning. The question worth asking, in my mind at least, is why so many people embrace of some sort of abstract notion of human “progress”. The answer to that question has more to do with ideology than evolution.

Liberal morality is a scam but far from unique. Mill’s ideology of moral progression is the alibi that ruling and managing classes use to obscure, enable, and protect their acts of capitalist systemic reproduction (disinformation, violence, etc.) as mere personal failings, which can be redeemed when enough innocent children scream about them, and which under no circumstances should be corrected through direct action.

Contrary to the public beliefs of the useless propertied classes that construct norms and deviance, discipline is not cost-free. In private, they know it’s a deliberate waste of our energy and attention.

Interesting, assuming that human type cognition is detrimental to a species survival, one wonders if this would be true for any species where ever they may be found. In other words, maybe it is a factor in explaining the Fermi Paradox.

This goes against the Darwin’s evolution theory without much supporting evidence imho.

If conscience is bad for us, why didnt evolution in the struggle of the fittest got rid of it?

The most interesting take on the origin of our conscience I think is from Julian Jaynes, I havent seen a rigorous rejection of his theory yet.

I thought Jaynes was on about consciousness, not conscience.

“A major problem with morals, however, is that they are subjective and can easily lead to justification for one demographic or cultural group’s oppression of another.”

A feature, not a bug. Morality provides justification for collective violence–right makes might. Morality subjective, no, arbitrary, yes, driven by the political as well as long-term selective pressure (e.g. the Shakers). If morality were not underdetermined, it would not be useful as a tool of politics.

Humans are what happens when you combine primates with insect social structures–and most of human civilization mirrors complex insect hive behaviors, as well as the nasty stuff like genocidal warfare. There can be no doubt that language and human cognition are integral to creating the human hive consciousness, and hive insects are pretty successful evolutionarily.

Starting from the top: you have entropy, everything is doomed the die and the sun to burn out.

Next, life consumes life in a constant struggle for existence.

When you get human collectives, human collectives are in perpetual struggles against each other, this struggle is created for structural reasons due to the inherent anarchy in the state of nature/international system.

Moreover, human collectives operate somewhere between parasitism and symbiotic, with elites gradually becoming more parasitic over time until the collective collapses or convulses.

No matter how smart or good intentioned you may be, you are not going to change any of the above.

Further, to the extent that we look for a fundamental ethics, it would have to be life-boat ethics, as any other ethics is expendable in a time of crisis.

Elites don’t have to exist. They were a bad idea we came up with 6000 years ago and we could shake them at any time, Diderot-style. Priesthoods such as the bourgeois middle class do have a tendency to not only project but enforce their own incapacities on others. Obviously priesthoods can’t exist without a ruling class (which have, at times including now, been one and the same).

Self-identity, that thing which supposedly makes intergroup violence necessary, is also a bad meme that we can shake off any time, but that one takes longer.

In a large group, you have to centralize decision making and this leads to elites.

Intergroup violence, while not necessary, is inevitable because groups invariably do not trust each other unless they are faced with a common and more threatening enemy. World peace would probably be possible if the Earth was invaded by space aliens in a war of conquest.

Extinction schmextinction! I want to know more about the dinosaur butt brains! [Healthy dose of irony intended] For those interested, after looking into it a bit more a found several good explanations including this one from the Smithsonian:

https://www.smithsonianmag.com/science-nature/the-double-dinosaur-brain-myth-12155823/

Alas, it wasn’t to be.

The article refers to “the misapprehension that all dinosaurs were huge.” A “misapprehension” only of those who are ignorant of the fact that every dinosaur (as far as we know) spent much of its existence inside of or newly hatched from an EGG, and even the biggest dinosaur eggs were “huge” only in comparison to those of chickens et. al.

Whether or not dinosauers had butt brains, there has been some indication that there are mini-clusters of nerves much like what one might call “mini brains” at different locations around the human body. In particular, it has been argued that there is such a cluster supporting the heart as well as the process of digestion.

The nerves around our gut has been called a second brain being as it is so complex and some of our physical reactions such as the physical responses to pain are partially in the spine. Just because an animal has clusters of nerves outside the brain does not make it defective or stupid.

The fundamental human problem is consciousness rather than intelligence. I agree with George Carlin — the first person on Earth woke up, looked around, and said “This can’t be it”. And we’ve been trying to escape or remodel the place ever since. All religion, philosophy, science, art, technology are efforts by consciousness to get to a better world, either by rising above this one or changing it to something that seems more suitable.

Welcome to Samsara, the endless, recurring, charnel house of existence characterized by old age, disease, and death.

The title of this post : “Downside of Human Exceptionalism” uses the term ‘exceptionalism’ — which has become a pejorative and acquires poison from its usage in the construct “American Exceptionalism.” Is “Human Exceptionalism” any more accurate than “American Exceptionalism”? Neither Americans nor Humans are especially exceptional — no matter how they may regard themselves. Humankind is not the only intelligent species on this beautiful blue planet. Humankind is not adept at understanding or communicating with the other sentient life of Earth. Of all capacities, I believe in the incomparable capacity of intelligence as a tool for adaptation. The present flaws of Human Society are not flaws inherent in intelligence … they are flaws in the present construct of Human Society, particularly its propensity to give power to some of its most flawed members. I cannot believe this is a flaw inherent in the quality intelligence. This is a flaw in Society as present Humankind has allowed it to be constructed. I cannot believe it must be a fatal flaw.

The idea that humans are inherently defective and a more animalistic mode of cognition produces superior beings occasionally appears in science fiction novels like Hellstrom’s Hive and Missile Gap, where it is supported by monsters (in the latter book, literally). Gregg turns this sinister position into a parody of progressivism by citing the supposed absence of racism and lack of climate change denialism in the animal kingdom as proof that they live a qualitatively better life. How are normal people supposed to react to this galaxy brain argument?

By submitting to their middle-class manager-masters. Managerial subjectivity is the whole object of the PMC, Wilsonian (“Our”) Democracy.

Human intelligence as a mistake. Maybe, but without, the proto hominids of three million years ago would have died out. Human intelligence is a tool created for the monkeys to survive the thenrepeated and unusually rapid climate change and being the prey of the many deadly predators of the time, many of whom were much larger than the current predators. The climate and ecology kept changing from dry to IIRC, monsoon, from open savanna to jungle, from waterholes, small streams, rivers, swamps, large lakes and back again. At the time, it was evolve or die, so the tool using abilities and social aspects then approximating chimpanzees were used not to die. I don’t know if they have found the causes, yet, but the evidence is there.

Maybe, tool using is a dead, but hominids and their immediate ancestors have been using tools for over three million years with the last non Homo sapien, Homo erectus, dying out about one hundred thousand years ago after being on the planet for over two million years. Interestingly to me, the great cultural awakening that happened around a hundred thousand years ago, happened just when H. erectus went extinct.

If I had to speculate, I think that the last of at least two genetic bottlenecks, aka, near extinction events, when humanity got down maybe to ten thousand or less people Earth wide forced us to power up the intelligence and tool making to survive. Maybe whatever caused the last bottleneck also killed Homo erectus after two and a half million years (and they have been found into the Caucasus, maybe a bit further north and out to most of Asia.

The book sounds really interesting. Will add it to my always-growing list of ones I want to read, although I am more into weeding out books right now because of a planned move. Of all the “things,” books are the hardest to get rid of. Even the not great ones, it seems wrong somehow to not preserve them. I am donating them for an annual book sale, though, so they will have a second chance.

This book review also makes me think of the excellent The Myth of Human Supremacy by Derrick Jensen.