Yves here. Please welcome seasoned finance and economics practitioner and commentator Satyajit Das, who is provided a three-part series on how major world geopolitical and economic structures are fragmenting as the US throws what is left of its imperial power on aggressively contesting the rising influence of Russia and China.

By Satyajit Das, a former financier whose latest books include A Banquet of Consequences – Reloaded (March 2021) and Fortune’s Fool: Australia’s Choices

Ordinary lives are lived out amidst global economic, social and political forces that they have no control over. Today, multiple far-reaching pressures are reshaping that setting. This three-part piece examines the re-arrangement. This part examines current great geopolitical divisions. The second and third part, which will appear on Thursday October 27 and Friday October 28, will look at key vulnerabilities and possible trajectories respectively.

There are decades where nothing happens; and there are weeks where decades happen“. The pithy phrase (the attribution to Lenin is contested) encapsulates periods when established orders are challenged and sometimes overturned, often violently. The question is whether this is one of those times.

Today, there is a sharp division between the ‘West’ – the US and its Anglosphere acolytes (Canada, Australia, New Zealand) supported unenthusiastically by Europe and Japan- and the rest of the world. While a simplification, the categorisation is helpful in understanding key contemporary events and potential changes to the current global order.

Points of Difference

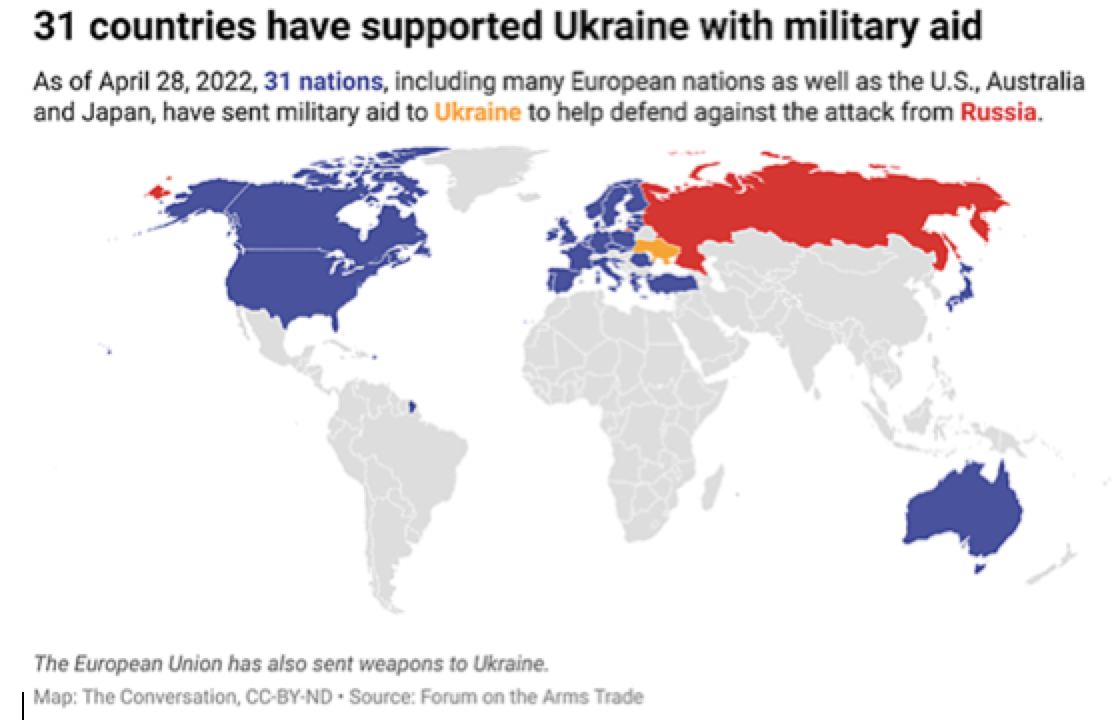

Positions on the Ukraine conflict highlight the schism. Support for Ukraine is primarily Western, representing around half of global GDP but less than 20 percent of world population.

Couched in platitudes about shared values and unity, Europe and Japan’s tepid support of the Anglosphere reflects competing priorities. Like the Anglosphere, they benefit from American military protection which lowers defence spending allowing resources to be used more productively. Despite a 2006 commitment to defence spending of 2 percent of GDP, NATO members average only 1.6 percent, with Germany, Italy, the Netherlands and Spain spending 1.3-1.5 percent. At the same time, geographic proximity to Russia and China as well as greater economic connections complicate allegiances.

Relationships between Germany, Japan and the West bear deep scars. The former has fought two world wars against its Western allies. The US and Britain reduced much of these countries to rubble. America deployed nuclear weapons against Japan with the ancillary objective of intimidating potential rivals. The rehabilitation of Germany and Japan served US post-World War 2 interests, creating bulwarks against the threat of communism. It reversed the original plan of reducing both to agrarian pasts unable to compete with America globally.

While urging a rapid end to hostilities, the majority of nations have been reluctant to condemn Russia’s actions, often professing neutrality. With an eye to its own regional territorial claims, China acknowledges Russian grievances. China and India along with most nations are sensitive about foreign intervention in their internal affairs. The West has highlighted recent public expressions of disquiet by Chinese and Indian leaders. However, there was no direct reference to or support of Ukraine. The comments mainly focused on the conflict’s impact on food, fuel and fertiliser supplies. Most nations prefer the benefits of maintaining relationships with all.

The conflict has unified the West against Russia and given NATO renewed focus. But Ukraine has also created a common cause for those with long standing grievances against the West. Countries such as Iran, a US branded member of the “axis of evil”, have sought to exploit the widening gulf between global factions. They have become suppliers of military equipment to Russia. This opportunistic co-operation exacerbates the global split.

The non-Western position reflects history. Associations are complicated by racially charged, exploitative colonial pasts, and experience of Western hypocrisy. There are legitimate questions about the support for Ukraine, especially the provision of generous financial and humanitarian aid, compared to that offered to forgotten victims of conflicts and disasters in the Middle East, Asia and Africa. The favoured treatment of white, Christian refugees has not gone unnoticed.

A Sea of Troubles

The avoidable Ukraine conflict, with its unnecessary destruction and human suffering, is best seen as a catalyst.

Unwillingness to recognise core interests of parties, increasingly entrenched positions, and lack of interest in negotiations means a spiral into a wider confrontation is not impossible. With escalation difficult to calibrate, the evolution from a proxy into a real war between the US and Russia, which might draw in China, all nuclear-armed, remains possible.

The West’s expressed desire for engineering regime change within Russia is dangerous. Any new regime may not be more amenable to Western pressure. History, most recently the Arab Spring and Colour Revolutions, shows that a dangerous political void is more likely than liberalisation.

Whatever the length, dimensions and outcome, Ukraine has exposed already present major differences in the world. In particular, the West’s response -trade restrictions, sanctions and asset seizures- will outlive the military actions and prove more damaging.

The weaponization of trade and finance, modern gunboat diplomacy, has a long lineage. Sanctions and blockades were used in World War 1 and influenced Japan’s entry into World War 2. Western embargoes against communist bloc countries were common during the Cold War. Since 1979, the US has sought to isolate the Islamic Republic of Iran established by a popular revolution which overthrew the Shah, who had been installed by an American coup d’état. Measures against Russia commenced in 2014. The US has imposed progressively more stringent restrictions on China covering exports and sales of critical technologies since 2018.

In the short term, the measures have affected Covid19 disrupted supply chains, aggravating shortages and price inflation, especially in food, energy and raw materials. In the longer-term, the interaction with other stresses may prove significant.

The effects of climate change driven extreme weather – droughts, floods, storms, wildfires- on food production and transportation links is accelerating. A triple dip La Niña alone threatens large scale disturbance with a potential global cost of $1 trillion (around 1 percent of global GDP). Resource scarcity – water, food, energy, raw materials- is simultaneously rising due to natural limits.

The decisions by major producers to increasingly stockpile or limit foreign sales to ensure domestic supply and control local costs are adding to disruptions to food production,. As of mid-2022, 34 countries had imposed restrictive export measures on food and fertilizers contributing to surging prices of key staples.

Energy shortages are not purely the result of sanctions on Russian oil and gas exports. Underinvestment, due to ESG compliant investors limiting funding for traditional energy sources, has affected supply. The necessary but over-hyped transition to renewables is a contributor. Proponents have overestimated its speed and underestimated the challenges of substituting existing generation capacity, reconfiguring electricity systems and converting industry and heavy transportation to non-fossil fuels. Shortages of critical metals and minerals, many non-recyclable, will retard conversion to new energy sources.

Given the world’s high energy needs, availability and cost will remain a major issue. Progress on controlling climate change, already inadequate, will reverse, perhaps fatally. Concern about emissions has been replaced by focus on energy security. A reversion to fossil fuels to lower prices and the cost of living is already apparent.

Slowing globalisation, which previously drove global growth, is another factor. Despite its benefits, greater economic integration has drawbacks. It reduces national sovereignty. Sharing of benefits and costs are frequently unequal. The 2011 Thai floods, the Tohoku earthquake, tsunami and resultant Fukashima nuclear plant disaster, and multiple episodes of extreme weather have illustrated the fragility of just-in-time production and tightly coupled global supply chains. The Ukraine conflict is the latest chapter in this history.

The 2008 Global Financial Crisis and Great Recession played its part. It exposed a key globalisation funding mechanic – large financial imbalances (China-US and intra-Europe). Germany and China needed the US, the world’s consumer of last resort, the Southern Eurozone and the Anglosphere to absorb their surplus production. The resulting large current account surpluses financed deficits in the consuming countries. 2008 underscored the risk of this strategy for savers – primarily Chinese, East Asian, German, Japanese and oil exporters. China’s Premier Wen Jiabao spoke for all when expressing concern about the safety and security of their capital.

The Western response to the financial crisis added to the disquiet and fed global division. The beggar-thy-neighbour monetary, fiscal and currency policies of advanced economies were destabilising for many countries.

China, Russia and India, to different degrees, saw the events of 2008 as signalling Western weakness and validation of their state controlled political and economic systems. It encouraged a distrust of the West and strengthened the belief that evolution into more open economies and societies was risky. Resistance to greater globalisation was the result.

While these pressures are likely to persist, complete deglobalisation and a retreat to autarky is unlikely in the short run. It is simply too difficult to replace intricate connections created over several decades overnight. More importantly, the effect on availability and cost of products would be great, reducing living standards. Instead, a dollop of decoupling is the most likely course. Increased re-, near- or friend-shoring of goods and services production is possible. Digital or e-globalisation may continue. But the retreat into distinct groupings or trading blocs – a us-and-them world- will be difficult to arrest.

Changes in the electoral dynamic are reinforcing the shift. Financial crises, economic stagnation, inflation, shortages, war and pestilence (the Covid19 pandemic) generate anxiety and fear. Politicians in all countries have exploited the instability.

Without tractable solutions, mainstream parties have largely lost their dominance. The appeal of strong, populist leaders has increased. Increasingly, the strategy is to put a reasonable face and emollient gloss over often unpalatable views in order to get elected.

Like traditional parties, the populists, both of the left and right, do not have answers to the major problems of the day. Instead they parade nationalist credentials and strong leadership. They target globalisation, elites (Davos Man), foreigners, immigration and overseas interference in domestic matters.

For democracies, the crisis is deepening. For existing authoritarian nations, it has strengthened latent instincts for centralised control, one party systems and repression.

The combination of these stresses have set up feedback loops which are now reshaping existing economic and power relationships.

Winners and Losers

All nations are affected by these changes, but not equally.

Functioning as an isolated entity or bloc requires a sizeable population, large internal market, self-sufficiency in key resources (food; water; energy; raw materials), necessary technologies and skills, and ability to ensure your security. The alternative is assured access to these elements from within your trading bloc or allies.

The sanctions imposed following the Ukraine conflict illustrate the dynamics. The limited effect, to date, of restrictions reflects the fact that Russia possesses many of the identified characteristics to operate as a near autarky. The absence of universal compliance also reduces the effectiveness of measures like sanctions.

Non-West countries, such as China and India, have an incentive to defy sanctions. They benefit financially from the ability to purchase oil and gas at significant discounts, sometime re-selling it raw or as refined products. Attempts at more complete enforcement, such as oil and gas price caps, may not be successful. It would require exclusion of all violators from global payments and insurance or imposition of secondary sanctions. But preventing access to insurance for shippers carrying Russian oil will disadvantage poorer countries but not large nations, like China and India, able to self-insure.

Jenga games of balancing cutting off Russian energy sales and ensuring adequate supplies to control prices was always going to be beyond the capabilities of economically-challenged bureaucrats and politicians.

China illustrates a different approach. It lacks self-sufficiency in food and raw materials, such as iron ore and energy. Strategic overseas investments, the Brick and Roads Initiative and leasing farmland target these deficiencies. Interestingly, Russia can supply a significant part of the Middle Kingdom’s food, energy and mineral needs although this would require reconfiguration of infrastructure. This process is already observable in global energy markets with Russian output being redirected East while Gulf and Australian supplies going to the West.

Having been relatively isolated until the 1990s, countries like Russia, China and India are not fully integrated into the global market system. Legacy structures are capable of reverting to a more closed economy.

In recent years, these countries have increasingly redirected policies and investment towards their home markets, abandoning reflexive globalism. The objective is the greatest possible independence and control over strategic sectors and essential products. For example, China has developed and sought to force businesses and population to adopt its Beidou satellite navigation system instead of the US GPS satellite system and Europe’s Galileo. In parallel, it seeks to export technology to build networks of client economies and governments frequently incorporating them into aid packages, soft loans and commercial transactions.

The West is more reliant on global commerce, although individual positions differ.

The US is substantially self-sufficient in food and energy. However, it has outsourced large components of its manufacturing and would have to re-skill its workforce to re-shore activities. It also requires export markets for its products – around 40 percent of S&P 500 companies’ revenue originates outside the US.

Canada, the UK, Australia and New Zealand enjoy varying degrees of food and resource self-sufficiency. Canada, Australia and New Zealand are exporters of food or raw materials. The UK is a significant exporter of services. All depend on imports of manufactured goods, a significant proportion of which is from China.

Europe and Japan are oriented to manufacturing exports, with significant reliance like the Anglosphere on Chinese demand. Both are reliant on imported raw materials, especially energy. Japan has a growing reliance on imported foodstuffs, with its food self-sufficiency rate having fallen to around 38 percent of calories consumed from 73 percent in 1965 because of rising demand for foodstuffs it cannot supply, like meat.

The West’s major disadvantage is its high cost structures, which have been offset in recent decades by imported cheap labour and raw materials. Europe, especially Germany, has tied its economic fortunes to the availability of low-cost Russian gas. If forward prices prove correct, then Europe’s gas and electricity cost would reach nearly €2 trillion ($2 trillion or around 15 percent of GDP). The high operating leverage in the case of Germany equates to around $2 trillion of value added production from $20 billion of imported Russian gas.

Attitudinal differences are important. Asiatic patience and memory breed resilience. A fatalistic acceptance of life’s constraints and caution about progress makes the non-West more resistant to setbacks and reversals.

In his 1933 work In Praise of Shadows, Japanese writer Junichiro Tanazaki captured this divergence: “We… tend to seek our satisfactions in whatever surroundings we happen to find ourselves, to content ourselves with things as they are; and so darkness causes us no discontent, we resign ourselves to it as inevitable. If light is scarce then light is scarce; we will immerse ourselves in the darkness and there discover its own particular beauty. But the progressive Westerner is determined always to better his lot. From candle to oil lamp, oil lamp to gaslight, gaslight to electric light – his quest for a brighter light never ceases, he spares no pains to eradicate even the minutest shadow.”

Changes in the existing global economic structure threaten Western living standards. The disruption of global trade and mobility during the Covid19 Pandemic and resulting shortages provided a window into these susceptibilities.

Mutual Misunderstandings

The fracture reflects fundamental differences in belief and values. Western thinkers, as varied as Montesquieu, Adam Smith, Voltaire, Spinoza and John Stuart Mill, were wedded to the idea that trading between nations could overcome tribalism, national identity and ideology reducing the risk of conflict. There was also an implicit confidence about the dominance of the West.

Late twentieth century globalisation, with its espousal of free trade and capital movement, was indivisible from this political end and propagation of certain values. Integrating previous antagonists like China, Russia, India and others into global trading arrangements would bring about political change helping strengthen the West’s position. The end of history would produce the suzerainty of a carefully crafted internationalist economic system which favoured the West. Under chancellors from Willy Brandt to Angela Merkel, Germany exemplified this policy of “change through trade” which created the now troublesome energy dependence on Russia.

But Chinese, Russian and Indian engagement with this Western agenda was always superficial. China was effectively bankrupt when Deng Xiaoping assumed power in the late 1970s. India and Russia faced penury in the early 1990s. Embrace of globalisation was driven by necessity not conversion to Western values or economic tenets.

Liberalisation, allowing greater private ownership and a modicum of free enterprise, was designed to boost living standards to placate a restive population. There was never any great desire for fully opening up and wholesale reform of the economic or political system. At best, it was marginal changes to the basic planned economy model. The central idea of an insulated system capable of existing in isolation from the West was never abandoned.

President Xi has repeatedly emphasised the Chinese Communist Party’s traditional leadership in government, military, economic, civilian and academic matters. He has preached self-reliance and rejected competitive democracy, the rule of law and the separation of powers as foreign ideas. Far from being reformers, President Xi, President Putin and Prime Minister Modi see themselves as restorers of their country’s proper place in the world.

As their economies grew stronger, the necessity for real change became even less paramount. The political threat, especially for China and Russia, was exemplified by Western orchestration of and support for regime change, such as the Arab spring and colour revolutions. It encouraged disengagement and reversion to centralised control.

In 1910, in The Great Illusion, Normal Angell famously argued that war was impossible because of economic interconnections. World War 1 undid those illusions. Today, the Ukraine conflict and related stressors are, in a similar way, challenging established geo-political and economic arrangements.

© 2022 Satyajit Das All Rights Reserved

This piece draws on an earlier series published in the New Indian Express.

Small quibble: #BRI stands for Belt and Road Initiative (not Brick). Glad to see references to “gunboat diplomacy” and “beggar-thy-neighbor” policies: exactly right. Further thought: China is referred to in the West as “the Middle Kingdom” which leads one to think there might be a kingdom above and below it (either figuratively or literally). A better translation would be “the Central Kingdom” as China views itself as being the center of the world, creating its own gravity.

The German term for China is “Das Land per Mitte.” The land in the Center.

There was a long ideology: The “tic-tac-toe” square. The number in the middle is always 5. It was the layout of archaic landholding, with the middle square being the commons on which pigs and other animals were pastured.

The reference to ‘In Praise of Shadows’ highlights the attitude of the Collective West as assumed by Adam Smith, Voltaire, Spinoza, et al and echoed by the lesser lights who lead today. Discontent with things as they are coupled with insistence that TINA to western leadership, dominance. Thus we find ourselves hearing with disquiet the reckless hints and references to the use of nuclear weapons. These scarcely veiled threats of annihilation trump the disgruntled child, who upon not getting its way, says I’ll take the bat and ball and go home.

I look forward to parts II & III.

In addition to being vague, orientalist stereotyping, I’m shocked anyone thinks this kind of resigned passivity is a virtue. ‘Shikata ga nai’ is a useful philosophy to have if it’s something genuinely outside human control, eg, constant earthquakes (though that also shouldn’t stop you from taking whatever steps you can to build more earthquake resistant buildings), but it’s a disastrous, and in fact reprehensible and irresponsible, attitude to have toward human affairs. We can debate the exact nature of ‘progress’, but not pushing forward is why China became prey for the West, and that’s a fact that was so blatantly obvious to Meiji Japan that they fell all over themselves importing western ideas so that the same wouldn’t happen to them.

There are many, many problems with modern Japan, China, and South Korea, but it is objectively better, by orders of magnitude, to be an average person in them now than it was a couple centuries ago. Junichiro Tanazaki was born into a privileged merchant family well into the Meiji Restoration. Make him a peasant born in, say, 1800, and see if he would have been so sanguine about the supposed virtues of passive stoicism.

It’s baffling to me that anyone can look at China in particular and see any kind of passive acceptance going on. Have you seen their infrastructure projects?

Or the vociferous protests for every single local or non-local issue that affects the Chinese population?

an aside: the Western political ideas since the Enlightenment about the importance of the individual in relation to the collective (democracy, bill of rights, etc) , are different from Eastern philosophies that promote both the importance of the collective over the individual and the passive acceptance of that relationship by individuals, imo.

Not all Eastern philosophical schools advocate that. It’s just that the ones that do ultimately got the most state and elite support, for obvious reasons.

Agreed. I was also stuck by this weird racial essentialism, especially in the form of a quote from an almost 100 year-old book. It seems unnecessary in what is otherwise an interesting and well-written article.

I think its striking how many people assume that greater international trade is a historical straight line continuum. In reality, there have been multiple cycles of opening up and closing on a regional or global scale. The world was highly globalised at the end of the 19th Century up to WWI, in many ways we are just catching up. If you go back further, its remarkable just how interconnected the Roman world was, not just internally, but elsewhere, including the east and China. In many ways, the opinion up of China (in particular) to western trade is just a return to older patterns. And as happened in the past, these can reverse.

Just one point on China. Das rightly points out how dependent the west, especially the anglo sphere has become on Chinese trade, but it works both ways. China has a very distorted economy (typical of new, rapidly developed nations) which is disproportionately dependent on its export sector to displace internal demand. China can theoretically become a near autarky (with Russian help) and prosper. But it would require as radical a set of internal economics changes to pull this off – at least as radical as needed in the West. From what I can see, Russia is in a much stronger position to prosper in a more fragmented world. Maybe India too.

Challenges to Chinese autarky, absent a catastrophic demographic implosion, include food and fuel dependency.

As well as the taxation system.

Thank you and well said, PK.

Within reach of where I’m sitting, I have a family heirloom that was sent from France to Mauritius in the mid 19th century, a wedding present that has been passed down. I know (Franco-)Mauritian families with similar from China going back to the late 18th century.

PK’s second paragraph has been noted by HSBC and Standard Chartered, firms that have operated there since the mid 19th century. Concern has been echoed by the UK regulators of these two, but of other UK banks, too. Much of that money is indirect and goes via Hong Kong and Singapore.

A study of early neolithic tombs in Ireland (I can’t find the link right now, but it was based on isotope and DNA studies on bone remains) showed a remarkably broad range of connections with what is now an isolated rural area of north-west Ireland. Some of the bodies were very local, others were from much farther afield in Ireland, and some showed clear evidence of originated from Sardinia and eastern Anatolia. These people almost certainly wandered regularly by boat from the Shetlands to the most distant parts of the Mediterranean and considered each others cousins (and given the evidence of elite level interbreeding even in the early neolithic), more than just cousins).

Many years ago I was camping (a very long story as to how I got there) on the Chinese/Mongolian border, by a salt lake on the fringes of the Gobi. The area was riddled with odd shaped mounds. On breaking them open, they were charcoal – the remains of generations of Silk Road travellers stopping by this brackish lake to camp. I was reluctant to be a vandal of these amazing remains, but even a little sorting around revealed little bits of metal and stone, including what appeared to be an Indian amulet, but could easily have been Persian or even Greek (sadly, a companion claimed it as a souvenir and I never got a chance to get it fully identified). Humans have been trading very long distances for a very long time.

Incidentally, I had a guest from HK stay with me over the summer – a student. He introduced me to a few of his family – the usual cosmopolitan HK/English mix. If even a fraction of the stories they are telling me are true, then HK is truly finished, along with many of those historic connections. I doubt if this is good news for the traditional English/HK banks.

“If even a fraction of the stories they are telling me are true, then HK is truly finished, along with many of those historic connections.”

Please tell a few of the stories you heard from your HK guest. I have a peculiar affection for HK after a brief visit there, many years ago, before it was absorbed by China.

To Satyajit Das – G’day. In reading this article, I am not sure whether it is a fracture or maybe an inflection point. Anyway, I have been trying to get a 10,000 foot view of some of the major factors that are behind this disordered world and maybe I have been reading too much Doc Hudson but could it be that the economic and financial system that our world uses just does not work anymore which is the root cause of all this chaos? I’m being serious here. Last I heard for example, world debt was north of $300 trillion and climbing. The stock market is packed with derivatives like so many cases of forty year-old, sweating dynamite and less than 1% of the world population is siphoning up the wealth of the other 99%. None of this is sustainable and yet nobody is really saying that maybe it is time for a new economic system. Consider this example. The present NATO-Russia war is actually an attempt by the West to crash and loot the Russian Federation to bail out the ills of our present financial system. So if this is true what I said, then it is an example of how a root cause of this disrupted world is an economic/financial system that just does not work anymore.

Rev, yes. Our current economic/financial system is out of balance. We are out of balance.

A chance remark the other day, by someone, somewhere: When the first Europeans arrived on the shores of Turtle Island (now called North America,) the indigenous inhabitants had no money, or what we now call money or currency. In the next 500 years, money has consumed the world. US GDP is composed mostly of money …. trading it, loaning it, securing it, creating it out of thin air. Much of the remaining GDP comes from extraction, destruction of our home.

Money allows us to distance ourselves from our fellow humans: we can buy them, instead of having to spend years nurturing bonds of interdependence.

It also allows the creation of great inequality, great power imbalances. Billionaires versus the 99%.

The Dine (known as Navajo) belief centers around a system of balance and harmony. A person, or a culture, that is ‘out of balance’ is sick. We have become lopsided with a love of money that overshadows our love and concern for our fellow travelers, and our concern for our dwelling place, in our brief sojourn on a planet that is all we will ever know of Paradise.

FWIW, where I’ve got with this is “super sociability” first set pushed us off from our primate cousins, after which “symbolic reason” gave us language, supercharging the speed of separation.

Math, to my mind at least, is a “spandrel”, inadvertently co-evolved with the capability for language. Language can say anything, math reduces everything to zero. Concomitant with settled agrarian civilization, math started taking on the characteristics of money and, where used as an abstraction of generalized real wealth, created the recurring debt traps for which Michael Hudson has described near eastern Bronze Age defensive adaptations.

Christianity temporarily reimposed a version of the near eastern debt trap accommodation that broke down when Leo X needed a war loan from Jacob Fugger. At about the same time, Spain began looting the Americas creating a loose money protocapitalist investment boom in shipping and military technology that when combined with coal at the dawn of the Industrial Revolution turned “the love of money” into a death cult.

Since the dawn of civilization money has bedeviled us with its false representation of wealth, empowering sociopaths to domesticate the heard of humanity into what the psychotic mind views as an extractive resource, periodically interrupted by spells of super sociability, like the Axial Ages universalizing and humane religions, that ameliorated the worst exploitations.

AGW now challenges us to a new height of super sociability, or extinction. We tell ourselves stories about how we collectively are, but in truth for the last 5000 years we’ve let ourselves be governed by math, granting money the absolute power Zero suggests and with it the coercive power of almost uniformly antisocial, predatory States.

Great perspective. Any notable groups pre-Pythagoreans that have contributed so actively/somewhat consciously to this pernicious movement?

I just read that story about the Europeans reaching North America in David Graeber’s recent book The Dawn of Everything, and how when the French arrived in Nova Scotia in the 1700s and they tried to change/convert the local indigenous population but the locals looked at the French society as degraded and savage. They said we are happy, we have no poverty, look at your society, look how you treat people, look at all your poverty and people just walking past needy people, you are the savages not us. And the local population soon realised it was the French concepts of money and property was at the root of their problems.

I concur, capitalism has simply run its course and is running on fumes, every last bubble you can think of has been attempted and every one of those markets is oh so toppy, with no buyers at these highfalutin levels, with the bubble that effects most all of us being worldwide in housing, where homes might be worth 25% of the previous high water mark.

I know lots of people who are home rich, but have a dickens of a time coming up with long green, cold cash, semoleons, etc.

If you have money in the bank and it just sits there receiving niggardly interest rates, kinda boring but safe. Yeah-lets not do that, was the theme since the turn of the century.

Through the magic of compound interest you can double your money in time to pay for your burial expenses, maybe.

Imagine a Los Angeleno whose abode is worth $200k after the dust clears. They were counting on the First National Bank of their Home to provide for them in their golden years, and the goods were odd but odds were good it’d come through.

I’m seeing a Max Mad future, and freedom’s just another word for nothing left to lose, and I sadly imagine lots of people losing it.

The bigger questions is what would replace western hegemony, er hypercapitalism should it go away similar to the Communist bloc party’s curtain call…

…is it time for 1 worldwide currency yet, in some guise?

Well said. Can’t help seeing the paradox of the west. On the one hand our “quest for the brighter light never ceases”, but out determination to maintain the status quo with respect to our economic/financial system, which is clearly failing all but a small minority, is in stark contrast to that notion.

Well, Doc Hudson has been saying just this, and it’s nothing new in history. He points to the ancient notion of Jubilee as an example of the conundrum past societies have wrestled with, when “this can’t go on anymore.”

A near example of “this can’t go on anymore”, it seems to me, was the dissolution of the British Empire after 1945. The Brits had a solution, though, which was another anglo power to pass the baton to: the U.S.

Today, the U.S. has no liberal Western power to pass the baton to. We are not even at the point, as a country, of recognition that we need to pass the baton. We’re like the Tory’s and Churchill who were “shocked, shocked” by the loss of the 1945 (1?) election of Attlee by a landslide. Everyone knew the jig was up but the incumbent leadership. Might November 2022 be a similar shock to today’s Democratic Party?

My sense is that we’ll need to pass the baton because this country is incapable of impartial leadership of the world. It will need to pass it to a multi-national entity that will administer a global trans-national reserve currency (like Keynes’ bancor) in a way that smoothes structural trade imbalances equitably, and that will be the final repository of the world’s nukes, submarines and aircraft carriers, retaining a modest peace-keeping force. My nominee for this entity is a much empowered U.N. or equivalent. And no UNSC veto.

A key assumption (which economists like me always make) is that humans are rational. We know that rationality comes only with great pain. As Churchill once quipped “You can count on the Americans to do the right thing–but only after they’ve failed at trying every alternative.”

I believe that there was probably never a chance for a “multi-national entity that will administer a global trans-national reserve currency”. The nearest the world ever came to multi-national entities to run the world were the UN and things like the World Bank and IMF, but these were mainly Western attempts to run the world under Pax Americana.

The possibility of this happening again is zero in the medium term. Large sections of the West’s own population are anti-globalization and they now have political power through anti globalist , and the split in the great powers caused by the Ukraine war means that this is not even on the table anymore.

The problem with the West is that mainstream political parties are captured by elite interests – and the managerial class (public and private) are bought into that system. Perhaps post WW2 there was some nod of the head towards the wider population. But now it is full on plutocracy, with just sufficient crumbs to the rest to keep them quiet. However, as the East / Global South grow stronger, there is reducing scope for exploitative trade, and consequently less crumbs to go around.

The majority of the population are worse off and know it. But they don’t know the causal factors because the mainstream political parties and mainstream media are too corrupted and indoctrinated to inform them. So they instinctively vote for “populist” parties etc: there is no functioning socialist movement, and “socialism”, “left -wing” are bereft of meaning, having been inappropriately deployed by both mainstream parties and by the media.

The growing chasm between the west and the east, can only be good long term for the east as they hopefully reduce elite control (both global and domestic).

Living in the London, one cannot but be depressed by the utter lack of awareness of a deeply propagandised society ignorant of the chaos that incompetent US / EU / UK elites have and are reaping, with Russia / China scapegoating and provocations, and decades of economic mismanagement.

Spot on!

globalization has not lifed living standards in the west, its reduced them. bill clinton said a intergrated world, no one would want to upset the apple cart. he was wrong of course, he mostly knew it was a lie. if anything, it creates massive imbalances, slower real growth, massive inequality, friction at all levels of society, debts, strife, starvation than war.

“Slowing globalisation, which previously drove global growth, is another factor. Despite its benefits, greater economic integration has drawbacks. It reduces national sovereignty. Sharing of benefits and costs are frequently unequal. The 2011 Thai floods, the Tohoku earthquake, tsunami and resultant Fukashima nuclear plant disaster, and multiple episodes of extreme weather have illustrated the fragility of just-in-time production and tightly coupled global supply chains. The Ukraine conflict is the latest chapter in this history.”

the quicker any western country gets it, what was done to them in the 1990’s, the quicker they can avoid strife, starvation and war.

The idea that free trade — globalization — increases living standards for all and somehow leads to greater mutual stakes in continuing amicable relations between nations and might somehow reinforce domestic reform and lead participating nations to play an increasingly constructive role in world affairs … makes a pretty story for globalization. I believe the reason motivating globalization is a much more mercenary desire to exploit labor arbitrage as means to break what remains of the greatly weakened, co-opted, and corrupt u.s. labor movement.

Rightly so!

Improved living standards have been brought by better technologies and better designs, which would have come anyways. Much innovation was in fact stifled by oligopolies.

The camera market, one I follow, is a good example. Digital cameras got very good and somewhat affordable in the 2010s, meaning they could shoot high quality stills and video, with good lenses. People started noticing that and bought a lot of cameras and lenses, myself included. Over the last decade+ the prices have quadrupled, and the technology has gone maybe 1.5x. And the cameras all lose value right away. And the companies are all failing.

Stupid managers. Kill them all.

JG has mentioned the two essential ideas that drove neoliberalism from the depression to the end of the war. This is discussed exhaustively in Quinn Slobodians’s book, Globalists This is the best source that I have found for the discussion of neolibralism.

i have always viewed free trade as being unconstitutional, this article touches on just that.

https://jacobin.com/2022/10/rich-rule-capitalism-us-constitution-political-economy-anti-oligarchy-book-review

“The center of this substantive constitutional vision is anti-oligarchical: a constitution of “We the People” that aims to “promote the general Welfare” and guarantee a “Republican Form of Government.” The Constitution, in other words, was meant to secure freedom for “the People” from the arbitrary authority of the powerful, who include not just public officials but more particularly powerful economic actors. Political freedom requires certain economic conditions, and, in that sense, politics and economics cannot really be separated. Fishkin and Forbath thus insist on the need to return to political economy in our constitutional discourse.”

The Way Magna Cart was for the nobles getting rights for themselves and diminishing the power of the Kings, US Constitution was drafted with the landowners in mind as “We the People”.

While in the Roman Republic, the long struggle between the plebs and patricians have curtailed the power of the senate and created a framework for tribunes of the people and other perks (hundreds of years of struggle), that is not the case in the US (maybe except the amendment regarding slavery).

“Without tractable solutions, mainstream parties have largely lost their dominance. The appeal of strong, populist leaders has increased…”

I’m going to be contrarian here.

I think it tends to go like this:

People start organizing for greater control over their lives and fairness (attempts at big “D” democracy, for lack of a better word at the moment))and then some faux “strong, populist” leader is bankrolled by the elite and hoisted in front of the people as one of the only alternatives – which always includes maintaining the status quo’s wealth and privilege.

I find it incredibly hard to believe leftists with strong ideological foundations have no answers to current predicaments; rather they’ve only got the answers the ruling elites do not want to hear. If you think left populists don’t have sufficient answers, it’s likely because they are actually left liberals, who are ideologically bound to the structure which exacerbates the disordering we are seeing.

The difference would be between, for example, Corbyn and Starmer. One is a man (in theory) for the moment, the other is a future loser-in-waiting.

I recall reading that Russian oil is expected to slowly decline in about 10 years. The fracking gas and oil in the u.s. is already in decline, probably a much steeper decline than that for Russian oil. The u.s. sanctions on Russian Petroleum and natural gas offers a nice vignette of the way that future diminished Petroleum resources could affect trade and patterns of our daily lives. We will see the impacts of large step increases in the cost of gasoline, diesel, heating oil, and natural gas.

I do not know enough about the problems Europe faces to comment on them. In the u.s. gasoline prices will impact all the suburban commuters and the current systems of distant retail. Areas with cold Winters will need to turn down their thermostats — a lot. The increased costs of diesel will affect the entire supply chain from origins to outlets. I believe the costs of electricity will increase. The higher costs for shipping have and will continue to lead to higher prices for the goods at retail. If we in the u.s. are fortunate, some of these impacts and the changes they work in re-structuring the u.s. supply chains will remain in place after sanctions are lifted and trade relations substantially return to a pre-Ukraine war status — if they ever do return to something close to what they were.

I doubt the u.s. will ever recover its national stature or former place in the world. I doubt the world economic structures will return to what they were before — but I cannot guess how they might evolve.

“But the retreat into distinct groupings or trading blocs – a us-and-them world- will be difficult to arrest…”

The tensions being described are exactly because the inclusiveness of the global economic order being described as disrupted was a fantasy of inclusiveness.

There is more recognizing that the global order led by the USA has always been about USA interests first.

US foreign policy and economic policy has always been “us and them.”

1948 memo by George Kennan spells out US foreign and economic policy.

When Satyajit writes, I read carefully.

I first got to know of him around 2000. I had got into the Bonds and Derivatives, seemingly by accident with absolutely no formal education in Financial Engineering So picked up Risk Management and Financial Derivatives: A Guide to the Mathematics (1998) and got myself some of the theory.

Not quite accidental, because in 1998 Weather Derivatives was a brand new field. I had an academic background in Oceanography/Climate and self taught computer skills. So got hired by a Weather Derivative startup on Wall Street to develop/code Pricing Models. The partners cum Traders, the Silverstein brothers got me upto speed on the Practical aspects of Pricing Derivatives. Around 2001 with WTC destruction the company went bust (long story). Then got the opportunity to move into Bonds and Derivatives including Credit Derivatives.

Anyway back to Satyjit Das. Very incisive thinking. He was also one who cautioned about a possible Financial crash as early as 2006 or so. Another was Raghuram Ranjan, with his 2005 paper “Has Financial Development Made the World Riskier”. I read them both and others such as Tanta (Doris Dungey) on Calculated Risk, and it all made sense because I was in the thick of it. I dont do stock market or bets, but this seemed sure. So made small bets (which I could afford to loose) against the market by buying out of the money PUTs. In the crash made 10X of the bets.

Incidentally Raguram Ranjans international high profile positions, he is still an Indian Citizen.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Satyajit_Das

It is very common to hear every day American’s say things like “take our Putin” . They took out Saddam and Gaddaffi …American world view is myopic , dangerous and barring Trump( irony) every president Republican and Democrat share this view of American Exceptionalism….even in a changing world.

Interesting platform where comments are equally interesting as the article.

I think the left (not the so called liberal left) has still some word to say but their voices are not heard in the mainstream media. I am 52 and I have not witneessed anytime so restricted debate on any matter on the mainstream media untill last couple of years. Personally, I follow news and opinions from alternative media sources like this platform but opinions of the majority is shaped by the mainstream media though I see weak signs that this is likely to change. If there will be a chance to solve the problems of the world, it will be only after more people realize that indeed there is no real debate especially in the western media, just a monologue, a propaganda. Or we will hit the bottom and “may be” learn the hard way, if we will learn. Pain may be teaching.

Looking at viewership numbers paints an even more terrifying picture of an almost forced apathy where people are aware of how bad mainstream is but don’t care to find other sources beyond the occasional tik tok news byte.