By Conor Gallagher

The longest-ever factory occupation in Italian history is taking place in Florence where the 300 workers are now making progress at turning it into a non-profit community cooperative that would pay the employees and produce products that would benefit the community. Should the workers succeed, it could provide an inspiration for others.

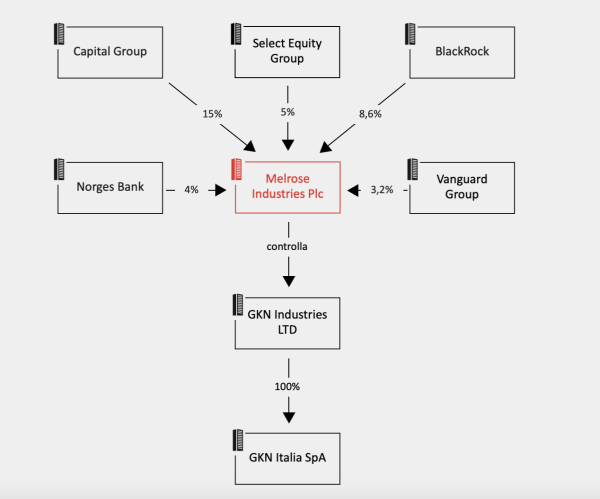

For three years workers at the former automotive parts factory, GKN Florence, were in limbo. According to Investigative Reporting Project Italy, in 2018 GKN was purchased by the British hedge fund Melrose, which went about enacting its motto of “buy, improve, sell.”

Investigative Reporting Project Italy

And in 2021 it was preparing to do just that when it abruptly announced the termination of the entire workforce. Instead the workers occupied the factory and have been there ever since.

Since the occupation, Italian labor judges have condemned GKN for its anti-union practices (in Italy a negotiated settlement is supposed to precede a business closure) for a lack of dialogue in the firings, and cases are open at the Ministry of Enterprise and Made in Italy, but importantly the workers did not rely on the government.

While workers are still demanding back pay, they’re also now trying to make “ex-GKN” a community cooperative factory – one that produces photovoltaic panels and batteries that do not involve the use of rare earths, as well as a cargo-bike painted in the same purple as the Florence soccer team. The idea is that the factory will serve the community and potentially the surrounding region. Francesca Gabbriellini and Giacomo Gabbuti write at Jacobin:

Parallel to the technical issues surrounding industrial plans and labor organization, the work groups focused on the issue of ownership structure, including by studying the possibility of a worker buyout. In Italy such operations are regulated by the Marcora Law of 1985, which provides for public funds to safeguard workers affected by attempts at industrial relocation or liquidation and who intend to take over ownership in a cooperative structure. Usually, with such processes, the startup capital is built up through workers investing their severance pay. But in the GKN case, the idea is that local supporters should play a leading role in reactivating production, as in the struggle itself. Thus the idea of the popular shareholder campaign was born, and dialogues began with Banca Etica (an Italian ethical finance body, which has been in solidarity with the GKN struggle since the opening of the Resistance Fund) and other such institutions.

The first steps are promising as they’re blowing past initial fundraising targets. In the second phase, to begin this summer, ex-GKN will launch an “equity crowdfunding” from small, medium and large investments.

The group says “the workers are directly involved in the management of the new production project.” Additionally, the plan is to include all “public and private investors, representatives of the region and all participants in the equity crowdfunding” on the board of the cooperative.

How Has the GKN Occupation Been So Successful?

First off, the workers who were already unionized made preparations early. As soon as they recognized that ownership was “boiling the frog” – or preparing to sell off the machinery and shutter the factory – they began to make plans to occupy. They realized striking or other forms of protest wouldn’t be enough as Melrose would arrange to have the machinery removed from the factory. They also did not rely on judges, elected officials, or any other outside group to save them.

The workers involved the community by partnering with other unions, green and other local groups, including including organizing the first Italian Festival of Working-Class Literature March 31 – April 2 in the occupied factory:

Dal 31 marzo al 2 aprile siete invitat3 al Festival internazionale di letteratura working class organizzato assieme agli operai del collettivo di fabbrica GKN di Firenze. Diffondete la notizia e aiutateci a sostenere il progetto: https://t.co/xDXPM0bDMq pic.twitter.com/nwFFuZ4jm4

— Alberto Prunetti (@alprunetti) February 14, 2023

Those connections were so strong that within a few days of the occupation, there was a general strike in Florence and more than 10,000 people took to the streets in support of the workers’ cause. Last month – nearly two years after the occupation began – roughly 15,000 came out to show their support.

Firenze, in 15mila al corteo ex Gkn: “Siamo una marea. Ci tengono a bollire a fuoco lento ma noi abbiamo idee e progetti per ripartire” https://t.co/qWr68BxwDe via @fattoquotidiano #26marzo

— Siciliano (@Siciliano741) March 26, 2023

Occupation is also maybe the most effective tool workers have. From Socialist Worker:

The main reason why sit-downs are so effective is that it is impossible for management to use strikebreakers to defeat a strike, since the workers are literally sitting on the means of production.

Secondly, whereas police customarily inflict violence upon picket lines–only to turn around and blame the strikers–it is much more difficult to do the same thing to workers occupying a plant. For one thing, it is somewhat difficult to attack the occupying strikers without damaging the company’s property. But also, it is much more difficult to charge sit-downers with starting the violence.

In contrast, the closure of a GKN plan in Birmingham was announced at the same time as the one in Florence. Despite strikes, negotiations, and angry condemnations, the factory closed, moved to Poland, and 519 people lost their livelihoods.

Ex-GKN Florence could become another Birmingham – albeit one that put up a longer fight, or it could become an inspiration in how to fight back against precarious work and build something run by workers and for the benefits of the community.

Could It Happen in the US?

While Italy has some current built-in advantages – namely unions that are still strong despite decades of conservative and liberal efforts to weaken them – both countries share a strong history of occupying workplaces at different points in the 20th century.

The Italian Biennio Rosso (two red years) saw more than half a million workers run their workplaces for themselves in 1919 to 1920 – although that eventually led to the fascist reaction of the Biennio Nero (two black years).

In 1936 and 1937, sit-down strikes and occupations spread across the US. It started in Akron, Ohio, when all the rubber workers at the Goodyear truck tire department sat down and refused to work in protest of a wage cut. Management quickly restored the old wage rates. Socialist Worker on what happened next:

By January 1936, 2.500 Firestone workers struck to protest the firing of a union member, in a sit-down that lasted several days. Against the strike ended in victory.

Soon the sit-down trend had spread to the auto industry and on December 28, 1936, more than 1,000 workers at Cleveland Fisher Body occupied the plant, demanding a national auto contract.

Within two days, the strike spread to Flint, Mich. Within three weeks, the strike would shut down GM operations not only in Flint, Detroit and Toledo but also at plants as far away as Kansas City and Atlanta.

By the end of the strike, 140,000 of GM’s 150,000 production workers had been involved in either a work stoppage or a plant occupation, making demands that included union recognition and a signed contract, the 30-hour week and six-hour day, a seniority system and union input into the seed of the assembly line.

In the first 10 days of February, GM produced only 151 cars in the entire country.

The 44-day Flint sit-down strike, which was led by shop floor militants and socialists, has become legendary–for its outstanding rank-and-file solidarity, which drew in thousands of workers from nearby cities, as well as its shrewd execution, which repeatedly outsmarted GM management in their attempt to force the strikers out of the plants.

After battles with police and the calling in of the national guard, the workers won a new contract.

It wasn’t that long ago (2008) that workers occupied the Republic Windows and Doors factory in Chicago. From Libcom.org:

On Tuesday 2 December 2008, officials informed the 300 workers of Republic Windows and Doors that the company would be shutting down in three days. Employees would not receive severance pay or accrued vacation pay. On Friday morning ownership also informed workers that they would be immediately cut off from their health insurance providers.

Two hundred and forty union members (Local 1110 of the united Electrical, Radio, and Machine Workers of America) voted to have a sit-in later on Friday. The sit-in participants carefully organized and orchestrated the action, dividing into three groups to manage and clean the factory equipment, provide security, and communicate with the media and supporters.

(Occupy Wall Street was influenced by Republic Windows and Doors, but we know how that turned out. Thanks Obama.) After six days, the negotiated settlement by Local 1110 with Republic and Bank of America provided the workers with the eight weeks of pay they were owed, two months of continued health coverage, and pay for all unused vacation.

Maybe next time, workers will go a step further and try to accomplish what ex-GKN is doing in Florence.

A little additional info on the workers from the old Republic Windows and Doors – they not only occupied their factory, they also started working for themselves, under the name New Era Windows Cooperative. Anybody in the market for windows in the Chicago area should definitely look them up. I’ve met a few of the workers, and they were all cool as hell.

https://www.newerawindows.com/

Thank you, so good to hear.

Great article. Bravi Italiani!

Great piece, Conor! Very encouraging to see this happening in Italy. And you also reminded us about the Flint sit-down led by the Reuthers and Republic Windows. I have one more source to add: a documentary by Naomi Klein’s husband about plant occupations in Argentina. “The Take“

Thanks for the shout out to the Goodyear and Firestone strikers. Those were bits of history I didn’t know about my former industry but mostly thanks for a positive article about factory workers. Stories like this are rare, and reporting on them even more so [the Republic Windows and Doors story being one of those rare instances].

Also in 1919 in the US there was the Seattle General Strike – https://depts.washington.edu/labhist/strike/

Strikers planned ahead and made sure food was delivered and hospitals were supplied during the strike. The take of one account I read years ago was that the usual suspects were so adamant about ending the strike precisely because of how effective it was – people were starting to realize pretty quickly that life went on just fine without the bosses needing to be in charge.

Solidarity!

My impression of u.s. labor law is that most/all actions by strikers that might be effective are unlawful and unlawful strikes are not protected by the National Labor Relations Board. I have little doubt that the u.s. courts would be easily swayed/nudged/bribed to declare strikes unlawful, hence unprotected by the National Labor Relations Board. I can only imagine the way ‘law’ enforcement might be implemented. Our police and Corporate private police get away with quite a lot and I doubt they would prove kindly or act gently toward ‘unlawful’ strikers.

I have not read the Patriot Act or the mission statements of the Department of Homeland Security, but my impressions of the definition of a ‘terrorist’ is fairly broad and probably applicable to ‘unlawful’ strikers and their leaders. The War on Terror is as over as the continuing spread of the Corona flu Biden declared over.

Perhaps I am mistaken in my impressions?

I think the Italians have the right idea, and workers in the US should take note: relying on the government to somehow support workers is a path leading to rapid defeat. If coordinated action by the workers is illegal, the law is probably (>95%) the problem.

With my previous comment, I am suggesting effective unionizing and effective strike actions have been outlawed — even re-categorized as ‘terrorist’ acts. The government and Corporate forces of coercion — the ‘Armies of the Night’– are better funded, better supported by intelligence operations, and far more ruthless than those of the 1930s, and probably more than those of the 1960s.

I also did not explore the problem that much of the manufacturing of the last century, along with machines and facilities to sabotage or sit-down at and occupy, are long gone and far far away. Perhaps u.s. unions, if — any remain worthy of the name — might attempt to establish networks of secret brotherhoods across the oceans. I believe globalization changes things somewhat.

Good occasion to recall The Take 2004 Occupy, Resist, Produce!

its a good article, and i am proud of the Italian workers. will they be successful? with free trade capitalism, discipline is the key, will capital go all out to make sure this fails?

in the U.S., the die was cast in 1993 for a Ayn Rand capitalist utopia. to late to reverse now, if it can be that is.

the unions stood a better chance with trump, not much better, but better. trump worked with the U.A.W. to make respirators and protective clothing. joseph biden broke the railroad workers unions.

Happy May Day!

The goal of this beautiful occupation is NOT a “worker-owned, non-profit factory” as Conor states. If you go to the link those words highlight you will NOT find a single mention of “worker-ownership.” The workers are forming a worker cooperative which is a MEMBERSHIP formation not one of ownership. A worker cooperative is like a common, not like a piece of property to be bought/sold/profited from.

The use of this phrase for cooperative structures has crept into common usage in the 80s by US (should be noted!) advocates of cooperatives (mainly non-profit developer organizations) to directly confront the rise of ESOPs that promoted themselves (incorrectly) as “employee-owned.”

If we are serious about a radical transformation of the economy, we need to disabuse ourselves of the language of domination and emphasize the language of freedom. Lotta Continua!

That said Thank You for this report!

Thanks akaPaulLafargue, While I do believe one of the goals is a non-profit, you’re right about “worker-owned.” Socialmente integrata would be better described as something like a community cooperative. I believe I was thinking more of Italy’s Marcora Law which helps workers take over ownership in a cooperative structure.

Thanks for your graciousness. Profits are a capitalist term – actually more the raison d’être of the system! Co-ops according to accepted terminology: “The co-op returns margins (net earnings) each year to users as patronage refunds, based on the amount of business each user does with the co-op.” https://www.thebalancemoney.com/how-a-cooperative-business-works-4800835#toc-cooperative-businesses-and-taxes

In worker-cooperatives (I was a member of one for two decades) funds remaining after essential costs and savings for future use were met were distributed to all the members in one fashion or another. Sometimes those funds are placed in a retirement account and sometimes distributed annually, or whatever the by-laws state.

Today, it seems to me, the historic utopian vision of cooperative ventures is diminished in an attempt to make them appealing based on entrepreneurial values (sic). This lack of vision works to support capitalism. Instead co-ops should be providing a radical cultural alternative to the inevitable collapse of capitalism. I have expounded these ideas here — http://www.ztangi.org/

Thank you, very important distinctions.