Yves here. This post makes a point with respect to commercial real estate (and private equity lending) that is not sufficiently well appreciated. While particular banks may has significant commercial real estate loans, many of these loans are syndicated and sold, either to CRE CDOs (which even in the 2008 crisis were vastly better structured than residential subprime CDOs) which are mainly sold to investors, or to credit funds (run by private equity firms) or to investors like life insurers, pension funds, sovereign wealth funds, and as Wolf points out here, REITS that focus on commercial real estate loans.

So while a CRE crisis could severely impair some banks (and therefore could create broad based concerns), there’s reason to think the level of risk varies considerably across banks.

By Wolf Richter, editor at Wolf Street. Originally published at Wolf Street

Four Class B and Class C apartment complexes, built before 1981, with 3,200 apartments in the Houston area – the Reserve at Westwood, Heights at Post Oak, Redford Apartments, and Timber Ridge Apartments – were sold at a foreclosure auction on April 4 in Harris County by the lender, Arbor Realty Trust, a publicly traded real estate investment trust that specializes in commercial real estate lending. Arbor Realty’s shares [ABR] have fallen by about half since November 2021.

Investors took the loss, not banks, and are still on the hook. As often in CRE, it wasn’t a bank that took the losses on the debt, but investors. We just discussed banks’ exposure to CRE debt, that 55% of CRE debt was held by investors of all kinds, such as Arbor Realty Trust, and/or guaranteed by the government; and we discussed just prior the huge losses some office towers dished out, mostly to investors and not banks.

The debt on the properties amounted to $229 million. According to Bisnow Houston, which confirmed the deal with Arbor Realty, the four properties were sold for $196.5 million in total, that’s $32.5 million below loan value, to Fundamental Partners, a New York-based private-equity firm.

Arbor Realty took the $32.5 million loss on the loan so far, plus foreclosure expenses. According to Bisnow, it continues to be the lender for Fundamental Partners. So it’s still on the hook for what’s left of the loan.

Variable rate mortgages taken out just ahead of Fed’s rate hikes. The former owner that lost control of the properties, Applesway Investment Group calls itself “a privately held investment firm focused on acquiring stable, income producing multi-family properties in emerging U.S. markets,” and pitches “passive income from high-yielding multifamily investment opportunities” to retail investors.

It had gone on a multifamily buying spree focused on lower-income properties during the free-money era, and funded projects with variable-rate mortgages. According to the Wall Street Journal, Applesway took out most of the loans in the second half of 2021.

This was perfect timing for variable rate mortgages: on the eve of the steepest rate hikes by the Fed in decades. According to data by Trepp, cited by the WSJ, the interest on one of the mortgages had jumped from 3.4% at origination to 8%. The purchase of at least two of the properties was financed with about 80% debt. Applesway’s losses amount to the equity portion of these properties.

In addition, Applesway was facing a $1.6-million lawsuit for unpaid work at those properties, according to Bisnow.

The Big Multifamily Default in San Francisco Hit CMBS Investors, not Banks

CMBS investors, not banks, were hit by Veritas’ default on a $448 million loan on 62 older apartment buildings in San Francisco. On the maturity date in November 2022, the joint venture between San Francisco-based Veritas Investments and affiliates of Boston-based Baupost Group refused to make the $448 million balloon payment. And they didn’t exercise their one-year extension option. They just defaulted on the loan. The loan has since then been in special servicing.

The floating-rate loan with a two-year term and a one-year extension was originated in late 2020, during the free-money era. The idea of much higher rates didn’t occur to investors, and they eagerly piled into it when the loan was securitized into two CMBS by Goldman Sachs: $344 million in GSMS 2021-RENT and $104 million in GSMS 2021-RNT2.

The loan is non-recourse; if investors eventually foreclose on the 62 apartment buildings, that’s all they would get, and the losses could be substantial. Given the condition of the San Francisco rental market, it would likely be the worst option for lenders. They really really don’t want to have to sell those buildings in a foreclosure auction, which would make a huge mess for other landlords too. Veritas has said that it is in talks with the special servicer. And according to Fitch, which rates one of the CMBS, it is looking for a partner to recapitalize the properties.

Floating-Rate Mortgages and New Supply

The special servicing rate of multifamily CMBS – an early indicator of trouble – has steadily increased since interest rates began to rise last year. In March, it rose to 3.0%, up from 1.7% in March last year, according to Trepp, which tracks CMBS.

Floating rate mortgages taken out during the free-money era are now causing all kinds of havoc beyond multifamily, including the defaulted Veritas loan, the foreclosure of the Houston apartment properties discussed above, and the default by PIMCO’s Columbia Property Trust on $1.7 billion in office loans, including two towers in San Francisco.

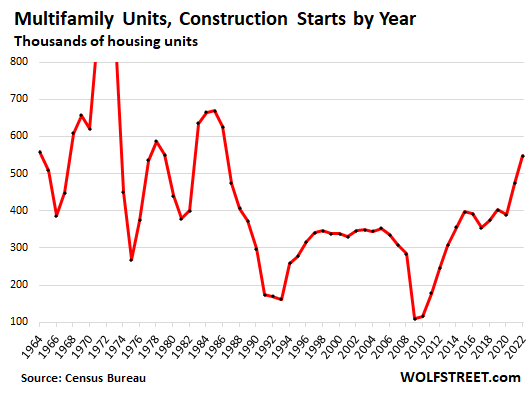

Boom of multifamily construction pressures older apartments. In 2022, construction started on 547,400 units in multifamily buildings of two units and larger, the highest since 1986, when the last multifamily boom ended. And it was up by 55% from the peak this millennium in 2005. And it followed the 473,800 units that were started in 2021, the most since 1987.

The construction boom has been driven by sharply rising or spiking asking rents and cheap money. But now, asking rents are no longer spiking and the cheap money is gone, and those units are coming on the market. These latest and greatest apartments with the modern amenities that people are looking for – much of it is higher end, because that’s where the money is – will find tenants if the rent is right, which triggers a flight to quality that pressures buildings down the line.

I’m not exactly sure if these are the example of problems in lending and property markets, but investor Barry Sternlicht has been quite vocal about the underlying issues in the property markets where his firm operates. If memory serves his firm is the landlord / property owner on many units in cities like Austin or Denver.

It will be curious if the above can perhaps, somehow, drive market rents down over the coming 6 to 18 months.

This link was posted in comments on water cooler late yesterday by wuzzy. Relative and worth reading. wuzzy’s comment: “An in depth discussion of real estate bubbles and climate change by weather guru Jeff Masters:” Bubble trouble: Climate change is creating a huge and growing U.S. real estate bubble

“…which would make a huge mess for other landlords too.”

A huge mess for S.F. landlords? That’s a damn shame.