Yves here. Depressing, but not entirely surprising. Military Keynesianism is making arming Ukraine less costly than it seems due to its impact on GDP growth. But this beneficial-only-in-the-eyes-of-economists spending does not include the direct subsidy of the Ukraine government budget, which has also become a very big ticket item.

By Mariia Chebanova, Manager for issues of financial system digitisation National Bank Of Ukraine; Oleksandr Faryna, Head of Research Unit, Monetary Policy and Economic Analysis Department National Bank Of Ukraine; and Slavik Sheremirov, Economist in the Research Department Federal Reserve Bank Of Boston. Originally published at VoxEU

Following Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022, many countries have supplied military assistance to Ukraine. This column discusses early evidence on the recent fiscal multipliers in donor countries. While it appears that the multiplier did not change materially following the first invasion of Ukraine in 2014 or in 2022, in the short term, an expansion of military spending due to the war in Ukraine may have a stimulative effect on output in donor countries. The economic cost of military assistance to Ukraine may be materially smaller when this domestic output effect is taken into account.

Following Russia’s unjustified full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022, 32 countries have supplied military assistance to Ukraine, with some dedicating almost 1% of their 2022 GDP. While military support for Ukraine is motivated primarily by international security and peace considerations, the fiscal expansion related to this war may have economic effects on the donating countries. In this column, we discuss early evidence on the recent fiscal multipliers in donor countries.

The idea of exploiting variation in military expenditures has long-standing support in economic research (e.g. Barro 1981, Hall 1986, Rotemberg and Woodford 1992, Nakamura and Steinsson 2014, Ramey and Zubairy 2018, Miyamoto et al. 2019, Auerbach et al. 2023). Much historical evidence indicates that the fiscal expansion driven by military spending is motivated primarily by geopolitical factors. The military support for Ukraine is a testament to this principle. Thus, by isolating the component of government spending that is independent of current and expected future economic conditions, it is possible to identify the output effects of government spending.

In our ongoing work (Chebanova et al. 2023), we estimate government spending multipliers for the period influenced by the war in Ukraine and the countries that provide military assistance to Ukraine. The government-spending multiplier measures the amount, in currency units, by which real GDP changes in response to a one currency unit increase in government spending. We find that, following the first Russian invasion of Ukraine in 2014, the government spending multiplier remained in line with the estimates obtained over longer historical periods. Moreover, the multiplier associated with military spending in 2022, a year that saw a dramatic rise in global geopolitical tensions, changed little relative to previous years. We also do not find significant differences between the multipliers for countries that provided military donations to Ukraine in 2022 and those for countries that did not.

How Much Military Support Was Provided to Ukraine in 2022?

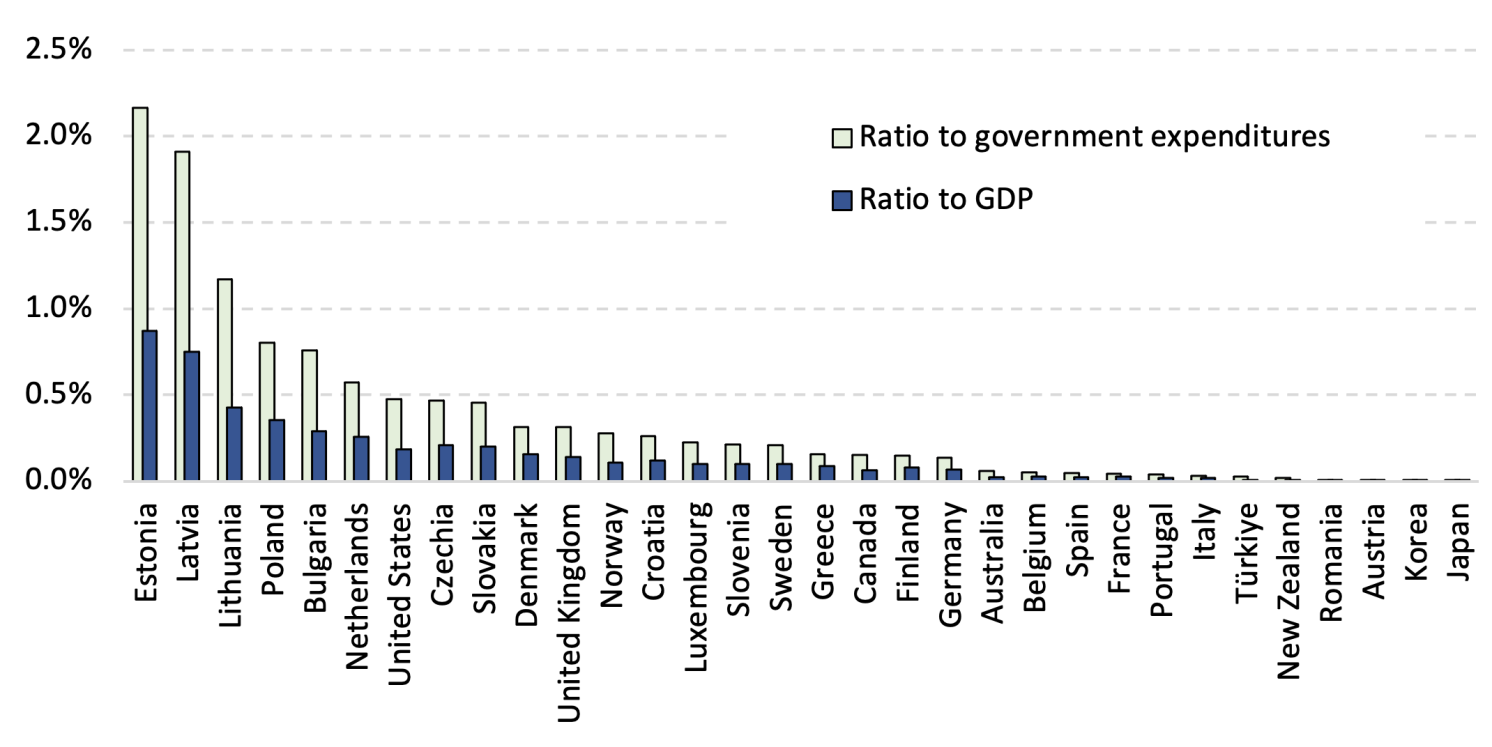

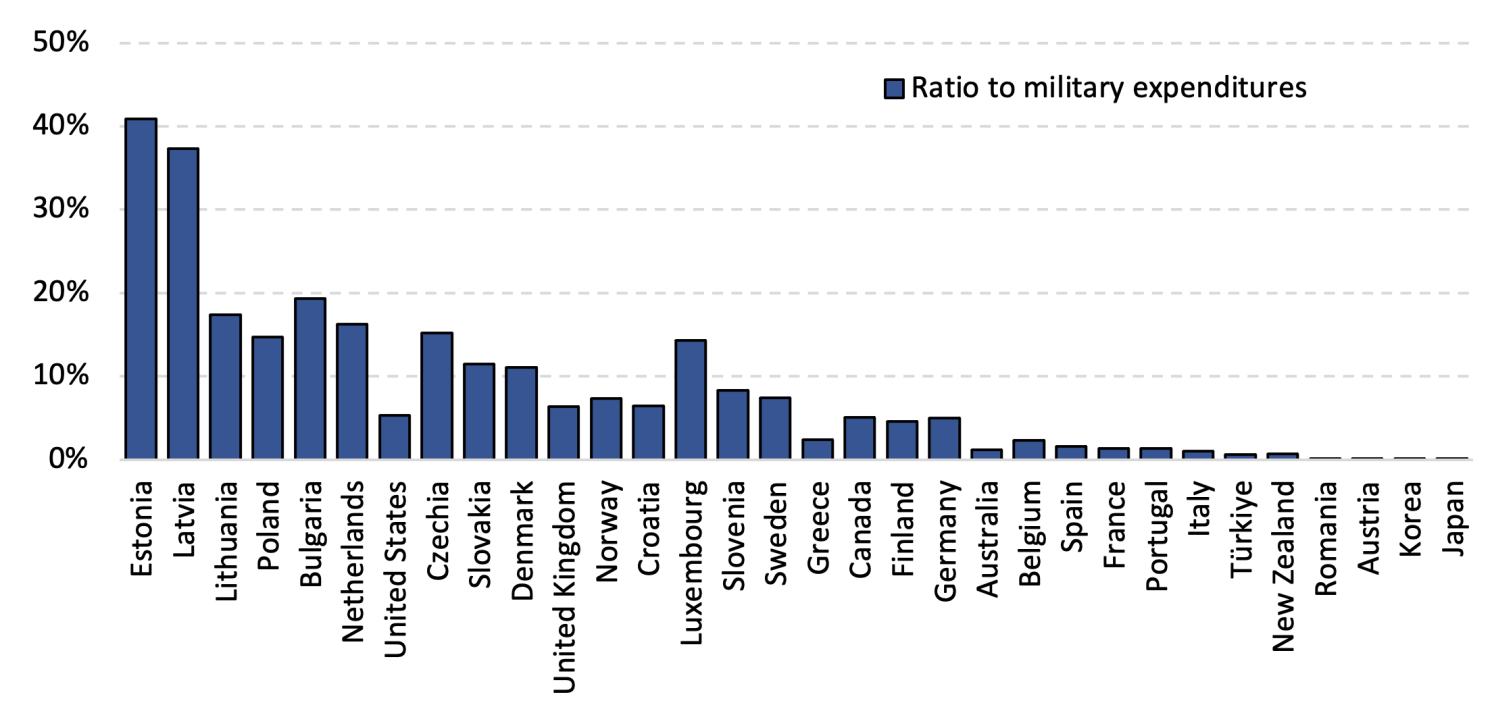

Prior to the full-scale invasion, military assistance to Ukraine was relatively small. The situation changed dramatically in February 2022. According to estimates by the Kiel Institute for the World Economy, total commitments of military aid to Ukraine over 2022 amounted to approximately $66.5 billion. This sum encompasses the cost of promised weapons, training, auxiliary services, and financing for the purchase of military goods. While this figure appears quite large in relation to Ukraine’s economy and past assistance packages, it constitutes no more than 5% of the combined 2022 defence spending of donor countries. At the same time, there is significant heterogeneity across these countries in the amount of military assistance to Ukraine relative to their domestic production, total government expenditure, and defence budgets (Figures 1 and 2). Countries that perceive a more immediate threat from Russia have committed a significantly larger portion of their resources to support Ukraine.

Figure 1 Military support to Ukraine as a ratio to GDP and government expenditures

Source: Ukraine Support Tracker from Kiel Institute for the World Economy; IMF World Economic Outlook.

Figure 2 Military support to Ukraine as a ratio to military expenditures

Source: Ukraine Support Tracker from Kiel Institute for the World Economy; Military Expenditure Database from Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI)

Fiscal Multipliers and Military Assistance to Ukraine

We find that, for the sample of 101 countries during the 2006–2022 period, the government spending multipliers are in line with those for the earlier period. We reach this conclusion by following the estimation procedure in Sheremirov and Spirovska (2022), whose sample ends in 2013. Specifically, we employ local projections (Jordà 2005) and instrument total government consumption expenditures with military spending. We normalise real GDP, total government consumption, and military spending by country-specific trend GDP and control for country and time fixed effects as well as the lags of normalised real GDP, total government consumption, and military expenditures.

We estimate that a $1 increase in military spending by the countries that supported Ukraine in 2022 is associated with a $0.65 increase in output within a year and a $0.79–$0.87 increase over the following two years. The cumulative multipliers decline at longer horizons but remain positive and significant for five years.

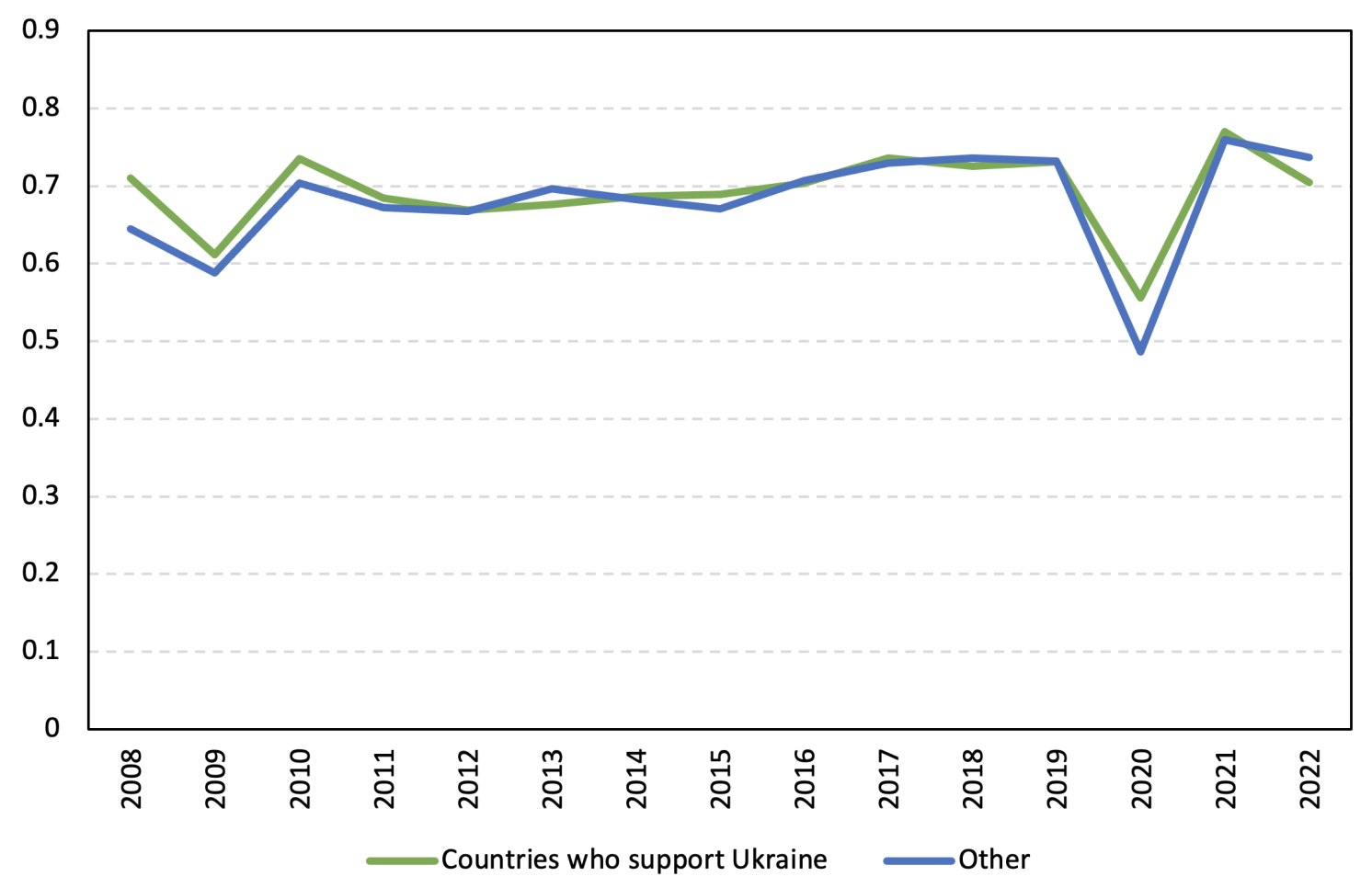

While the multipliers for donor countries are slightly larger than those for countries that provided no military assistance to Ukraine, the differences between the estimates for the two groups are small and not statistically significant at conventional levels. The multiplier appears to be remarkably stable over recent years, with the only noticeable dip occurring during the Covid-19 pandemic (Figure 3). Thus, it appears that the multiplier did not change materially following the first invasion of Ukraine in 2014 or in 2022.

Figure 3 On-impact government spending multiplier over time

Is This Time Going to be Different?

Because fiscal expansion tends to have stronger output effects over longer horizons, and military support for Ukraine is ongoing, these early estimates will be reassessed as more data become available. There are, however, reasons to believe that they may indicate the lower bound for the output effects of military support for Ukraine.

One such reason is that in 2022 much of the military support provided to Ukraine took the form of transfers of existing military equipment and ammunition. As domestic production in donating economies ramps up over the next few years to replace that equipment, a rising proportion of military spending could be directed to durable capital goods. Furthermore, the effects of public spending on military research and development can spill over into other sectors (Moretti et al. 2023) and stimulate aggregate demand and aggregate supply simultaneously.

The government spending multiplier could be much larger in recessions than in expansions, because in recessions labour and capital are underutilised (Michaillat 2014). Some forecasters (e.g. IMF 2023) predict a slowdown in economic growth and more economic slack. If their predictions materialise, a stimulus to aggregate demand stemming from military support for Ukraine may come for many countries just at the right time.

Some of the fiscal expansion due to the recent rise in defence spending could be offset by fiscal consolidation elsewhere. But history teaches us that in most cases total government spending rises following the onset of an unexpected external war. Moreover, some influential studies (e.g. Auerbach and Gorodnichenko 2012) document that the government spending multipliers associated with military expenditures can be larger than the multipliers associated with other types of public spending. Thus, even if rising defence spending has a limited effect on total government spending, its effect on output could still be stimulative in the short term.

Finally, the means through which defence spending is financed can substantially affect the size of the multiplier. Recent analyses (Rathbone 2023) indicate that taxes typically change little in response to defence spending associated with short wars but tend to rise if a country needs to finance a prolonged war. While this suggests that the short-term stimulative effect of defence spending may eventually evaporate, defence spending could pay a ‘peace dividend’ in the long term through increased global cooperation and national security.

Conclusion

Following the full-scale Russian invasion of Ukraine in 2022, many countries provided substantial military assistance to help Ukraine defend its sovereignty and territorial integrity. The long-term geopolitical benefits from promoting global peace and security as well as the cost of assistance have been discussed widely following the invasion. Based on our ongoing research that focuses on estimating government spending multipliers, this column discusses an overlooked point: in the short term, an expansion of military spending due to the war in Ukraine may have a stimulative effect on output in donor countries. Our analysis implies that the economic cost of military assistance to Ukraine may be materially smaller relative to the case when this domestic output effect is ignored.

Authors’ note: The views expressed herein are those of the authors and do not indicate concurrence by the National Bank of Ukraine, the Federal Reserve Bank of Boston, the principals of the Board of Governors, or the Federal Reserve System.

See original post for references

Not only in the eyes of the economists, I think. Also in the eyes of Western politicians who could use this to defend their policies.

Which I take to be the reason that this article was written — further justification, feeble as it is.

The obvious counterfactual being what if these countries spent an equal amount on investment in the wellbeing of their own people? The question in late capitalism is, I realize, absurd as far as these authors or their paymasters are concerned.

Somebody needs to interject, “Excuse me, but I don’t think you realize that time itself is a finite commodity; when it runs out productivity implodes.” After many war-cycles the political resolutions cannot ever be efficient enough to repair the environmental damage and the earth becomes exhausted and polluted. And the politicians all pretend there’s nothing to see here. War is the laziest, filthiest, most wasteful and irresponsible way to run a planet, yet militaries are the most disciplined and single-minded of any industry. There is a huge disconnect here – at the nexus of human determination and denial. I’m just a dummy but even I can think of some good ways to turn this oxymoron around. Before it’s too late.

Oh, definitely. But it makes a sort of sense. They would never do that, but they could spend on war and perhaps a little bit will trickle down to some of the population.

This is just about the stupidest so-called economic analysis I have ever read. I am reminded of what my freshman economics professor told us regarding GNP and such statistics. He introduced us to the ideas of Thorstein Veblen before Michael Hudson´s work made them popular (it was one of the many universities at which Veblen had taught). He would note that the practice of manufacturing stuff and then shooting it all off into outer space (these were the days of the space race) was a great way to increase GDP. Manufacturing all the wonder weapons to ship off to Ukraine is the same kind of stupidity. Shooting off all the automobiles we build into outer space would be about as wise. No worry about lack of demand!

The second idiocy the authors try to slip over has been noted below by Piotr Berman. Estonia´s expenditures on military aid does nothing for their economy as they do not mmanufacture it. Treating the whole 101 countries as if they were one economy is more than ordinarily deceptive. The economic impact on the countries that ¨contribute¨ to the carnage needs to be looked at individually.

Finally, I have seen estimates of the skim that these ¨contributions¨ are subjected to – not just by corrupt Ukranians, but by corrupt EU, NATO, and US actors. The deluded authors of this mish mash would be better advised to study the negative impact of these billions of dollars/euros in regards to the increase of crime, corruption, violence, death, destruction of infrastructure, and so on.

Does anybody know which ‘donations’ are actually to be billed to Ukraine ?

“in the short term, an expansion of military spending due to the war in Ukraine may have a stimulative effect on output in donor countries. ”

I guess the best way of testing this hypothesis is to collect the data on the impact on Estonia and Latvia where the expenditures related to the war in Ukraine are the highest when divided by GDP. I do not expect arms makers to significantly increase work places there etc. while on the civilian side, they lost a lot by participating and initiating sanctions, loosing transit revenue, market etc.

Any “stimulus” of that nature would be greater if it were directed at the civilian economy, with possible exclusion of boondoggles. Boondoggles hire people, need supplies that are often local etc. Well designed public expenditures can have vastly higher multipliers.

I am in Spain this week and happened to ask a local realtor who is an acquaintance whether British people were still buying property here. He said not really but there are plenty of buyers from the Baltic countries.

Anecdotal obviously, but money would appear to be washing through the system to the benefit of certain neighbouring countries in east Europe.

Thank you, John.

Anecdotal, too, in the Thames valley and Cotswolds.

I’m going to Normandy in late August and will ask there.

Fiscal consolidation, which was a priority, has gone nuts with Ukraine spending of which military spending is only a part and probably not the largest (about €20 billion by some accounts). There is a part that might have greater societal stimulus which is that of the “energy independence plan” with about €75 billion but other parts such as costs for Ukrainian migrants (€30 billion) and to reduce impact of fuel prices (€50 billion) sound more like money transfers without stimulus. (Source in Spanish)

What is for me very important to note is how this shows that “fiscal consolidation” presented as the great economic virtue and value is an arbitrary thing that can be forgotten when it is considered convenient, in this case to support a proxy war. Interesting also that this article focuses only on military spending and it looks very much as whitewashing precisely those kinds of expenses.

Note also that this being true, the stimulus effect, might create a “vicious” stimulus in countries like Estonia and Latvia which quite possibly have become economically motivated to support the proxy war.

Summed up in two words.

Broken windows.

I was just about to make the same point ;) What’s the multiplier effect of nuclear weapons?

Creative destruction?

Yep. War is a racket. Note, though, that the countries to the left of the USA in the two graphs all are small. So how much money are we talking about from Estonia, population 1.5 million + an enormous grudge?

Look at the right on the two graphs: Spain, France, Portugal, Italy. Looks like no appreciable economic effects to me.

Noting: ” We find that, following the first Russian invasion of Ukraine in 2014, the government spending multiplier remained in line with the estimates obtained over longer historical periods. ”

Did I miss something? No one is talking about 2014 as a Russian invasion. It the year of the cookies coup d’etat and beginning of open season on the Russian minority.

Yet consider the source: I remain skeptical of a bunch of Ukrainians zelenskysplaining us about how their scam is just the best thing for the world.

I saw the same thing. The 2014 invasion was Ukraine invading itself.

I have seen a lot of articles since 2/24/2022 that refer to Russia invading in 2014. And they will show maps of Ukraine in which the area occupied by the people of the Donbas fighting Ukraine in the civil war is referred to as “territory held by Russia prior to 2022”. However no one ever gives a date for when Russia left Ukraine (to reinvade in 2022) or an explanation for how they invaded in 2014, never left, and then invaded again in 2022.

I remember Western articles circa 2015 claiming that the uprising in the Donbass was a fake – just a cover for Russian special forces, which were supposedly doing all of the fighting. Locals were not really in the picture according to this take. I don’t think Ukrainians themselves were ever under such illusions, but it could be useful to pretend.

I believe this is a reference to the annexation of Crimea. The Russian troops who left their base in Sebastopol to protect the referendum from Ukrainian interference was an ‘invasion’.

It is common for western writers and pundits post 2022 to refer to Russia occupying parts of the Donbas prior to 2022. In looking for one I found the Wikipedia article Russian-occupied_territories_of_Ukraine doing it. That article does something I haven’t seen before. It makes an attempt to explain how Russia could have invaded the Donbas in 2014 and occupied it since then, and then invaded in 2022. It does this by referring to the 2022 invasion as a “full-scale invasion”.

Does that economic “multiplier” work if all of a sudden major European cities, even US cities, major supply centers and factories are reduced to smoking, or even radioactive holes in the ground due to bombings, possibly nuclear strikes?

There is no multiplier.

It seems Mariia consulted Chat GTP to spew indecipherable bullshit.

Note that $1 spent after one year only generates $0.65, so a loss of 35 cents and then ambiguously uses the word “and” to insinuate that the next two years increases the gain by $0.79-$.087 on top of the 65 cents when, in the best case scenario after three years the loss is 13 cents. At least that’s how I read this, because I don’t see how spending a buck to lose 35 cents over a year is going to make you 87 cents in the next three.

Basically the post is, demented groaf uber alles. What about the opportunity cost of killing and maiming huge numbers of your children? Were they not supposed to be functioning economic units generating surplus value for the country?

I forgot to add the sarcasm tag at the end of my post.

Since this is a Ukrainian study justifying sending money to the Ukraine, allow me to be dubious about this whole idea. Consider this. The EU is borrowing the money that they are giving the Ukraine and if you think that the Ukraine is ever going to pay that money back, well, I have a bridge to sell you. This means that not only will the EU have to pay back the money borrowed but also the interest that is levied on this loan. And this means that those EU countries will have to make savings elsewhere in their budget. Since an expanding military budget is locked in already, this will have to come from social spending expenditures. What will this mean? Austerity. This idea never works but ends up crippling a country’s ability to generate an economy so that it can pay for its expenditures and will also have the added effect of narrowing the tax base. The end of cheap energy was bad enough for the EU but austerity will hobble it.

Military spending in any case only benefits a narrow portion of the economy and generate little employment. And unlike economic activities like building infrastructure to expand your economy with, military spending is devoted to building weapons that for most of the time is left in storage where more money has to be spent to maintain it. The fact that so much of NATO’s military equipment that was sent to the Ukraine was basically junk as it had not been maintained or updated show this to be not a very good way of spending resources. In any case, military spending is rife with fraud in most countries and as an example, I read today that Boeing is charging the US government $52,000 for a trash can in a plane. So now you are talking about lost opportunity costs here. If that trash bin actually cost $20, then that means that $51,980 was not available anymore to spend on roads or hospitals or ports and the like.

OPPORTUNITY COSTS had been a mysterious term to me until recently, and I hope lotsa others in “the part of the world that counts” begin to see what the young people in Extinction Rebellion viscerally understand.

Rather than mild disappointment in the downside of the war economy being portrayed in upbeat econospeak, it’s time to pry the glossy veneer off the squalid future this piece defends.

Right… it’s OK to drown a thousand years of coastal development because the rising sea will force replacement of vast quantities of construction, boosting “beneficial” numbers while millions are displaced and CO2 emissions run wild.

This is a rerun of the satirical “benefit” of a 50 year old divorcee whose heart attack and cancer boost business while joining in a five car pile-up on the interstate.

“zelenskysplaining us,” indeed!

Opportunity costs always have sacrifices and I learnt this through a story from the Vietnam war. This guy was visiting some Aussie troops at a small base and they were complaining and moaning that they had not had a beer in ages. The guy asked them what they were talking about as they were having packs of Aussie beer delivered to them at their base. So this “digger” explained that yeah, they were delivered beer but they were selling them on to the Yanks up the road. At the high prices offered for that beer, they could not resist selling it on rather than drinking it themselves. :)

Gideon Rachman in the Financial Times has written an article headed:

Europe has fallen behind America and the gap is growing

That fits with Professor Hudson’s take that the Ukraine war is a war on the EU by the US.

I agree with your assessment that Ukraine will default on the budget support. On top of that I think that not all of the military “aid” is aid – in fact it will also come at the price of future debt that Ukraine – or whatever is left of it – won’t be able to repay.

Coupled with the staggering losses among the active male population and the emigration of a large share of the rest it simply amounts to NATO-sponsored dismantling of an entire country.

Exactly. I am waiting for the other shoe to fall.

Absolutely yes! You got it the way it is: a “smart” way to stole EU money by US and their east controlled fake republics!

Agree. This study is junk propaganda

Most of the countries to the left of the USA in these graphs border Russia and have in the past been invaded and dominated by Russia (excepting the Netherlands). There are a few to the right with a similar history spending perhaps a bit less but nonetheless trying to or successfully getting into NATO, including Finland and Sweden.

While economics play a large role in the European/global response … there is more in play than that. People also care about their sovereignty and are indicating a choice about the type of future they prefer — cost them what it may.

Hungary is not even on the graph, given its refusal to provide any military help to Ukraine. And it was invaded by USSR in 1956 and had a chunk of its territory passed onto Ukraine at the end of WWII.

Romania has also potentially a big bone of contention with Russia. R of Moldova was taken from it, taken back, re-taken by Russians, etc. After WWII, Northern Bukovina and the Snakes Island was passed to Ukraine from Romania.

But the Hungarians nor Romanians think themselves as necessarily superior to the Russians, and thus carrying a deep hatred for being bested by some inferior peoples. And them being neighbours to Ukraine, they know the lot as being worst than the Russians, being an infatuated lot, like the Poles, especially the Ukrainians from the west, many Catholics…

An article written by academic Ukrainians translated into good English presumably by the Boston Federal Reserve member of the authoring team. How is it possible to read this with a straight face? I tend to heavily discount its premise and entirely predictable conclusion — which is that spending money in the West on Ukraine is an economic boost to economies supplying war materiel to the country. Because ramping up production of new replacement weapons and ammo spurs economic growth. Wow, thanks, Ukraine! What would we in the West do without you? You’ve handed us a rare opportunity indeed! Now, let’s bring on a war with China, because that necessary economic expansion will dwarf the piddly-ass increases needed to supply Zelensky and company.

I don’t know, after 75 years on this planet, I’m now surrounded by “modern” BS palmed off as serious. Excuse me, I have to get ready for Pride Month(s) coming up in our small city. Mud-wrestling between drag queens and lesbians is one event. Suitable for all ages, of course. Have to widen the horizons of children, don’t you know. Oh, but remember to hate Russians and Chinese — Russia is trying to take away these freedoms from us with outdated unenlightened social mores and unjustified invasions, while China has stolen all our jobs and we want them back.

Apparently a mixed-market social democracy, the idea of which I first treasured six decades ago and retained as a way to keep capital honest, and the pursuit of peace in international relations, all of it has turned me into a raving conservative old fogey with out-of-date values. Now we need war! We need bullsh!t gender tropes and in my face proselytizing of same! We need zombified children! Screw the blind and disabled! Screw the poor and homeless! Screw the blacks and Latinos! Screw the environment! Instead promote niche concerns as incredibly important. We also need to further rape the Earth’s resources as fast as possible to generate jobs! C’mon, you know it makes sense. It’s the economy, stupid. And if we do all that, why everything will be fine. Except for individual wealth inequality, which will remain as a fundament of the ruling class. I have so much to thank America for.

In the background as I type, a CBC Radio newsreader intones : “Ukraine is still trying to kick Russian invaders out of its territory.” You don’t say? Well, we’ll all have jobs for a while until the “still trying” stops, I guess. Paradise. If you can afford the rent. No, I’m not bitter. /sarc

Talk about putting lipstick on a pig.

If this sort of thing works for donor countries, should not the Russian economy be white hot?

What needs to be added here is the support for reconstruction, which is already barely 1% of the money spent on destroying the country. From this comparison, the purpose of war is clear, it is to profit war makers, the cost of peace and reconstruction is always given less priority. NATO needed another war after Afghanistan and the Middle East color revolutions to keep the arms inudstry growing and Ukraine was next on the list.

As Nuland said ‘fuck the Europeans’

Isn’t this just a bigger version of Bastiat’s ‘Broken Windows’ fallacy?