By Lambert Strether of Corrente.

Loper Bright Enterprises v. Raimondo (Loper), to be decided in this Supreme Court term, is an even bigger case than United States v. Google Inc (Google). Google has indeed been brought by the FTC against a ginormous and heinous Silicon Valley monopoly; but Loper could strike at the heart of the “administrative state” itself, hence at the FTC’s rule-making authority (or even at its very existence).

Unfortunately for both of us, IANAL, and the conservative war against the administrative state has generated an enormous literature, replete with grudge matches, which it’s beyond the capacity of this humble blogger to master (at least in one post). I am tempted simply to reduce the petitioner’s views to the beastly frothing and stamping of the monied classes and their public relations service providers — law firms, think tanks, economists, and such-like — because somebody’s trying to drag a bit of profit away from their jaws and claws (with very little justification other than pique, I might add[1]). But I don’t want to be more unfair than necessary; sadly for both liberals and the left, it’s clear that all the passion and the intellectual energy is on the right, so it’s necessary to examine at least some of their arguments.

As a sidebar, I should, before proceeding, point to the current liberal assault on the corrupt and repellent billionaire’s boy toy, Clarence Thomas, and the subsequent moral panic, which has — and I know this will surprise you — turned out to be motivated:

I’m calling on Justice Thomas to recuse himself from consideration of Loper Bright v. Raimondo.

He hid the extent of his involvement with the Koch brothers’ political network, which has spent tremendous capital to overturn longstanding legal precedent before the Court next term.

— Senator Dick Durbin (@SenatorDurbin) September 23, 2023

I agree with Durbin, but where is the argument on the merits? Surely, stare decisis is not the most effective defense in the political arena? That is, the assault on Thomas is also an assault on a vote for Loper, as was, some would urge, the moral panic during Kavanaugh’s nomination, another case of refusal to argue on the merits. (Why not just say that Kavanaugh’s views make him unfit for the Court?) The head-counting is even more dicey given that Ketanji Brown Jackson, a reliable liberal vote, has recused herself because she was part of the circuit court that first heard the case. Hence only eight justices will hear the case, unless Thomas caves, which he won’t. End Sidebar.

First, I will look at the cause of action in Loper (herring, if you can believe it). Then I will look at the “Chevron Doctrine” (Chevron), which Loper‘s advocates seek to overturn, and its role in undergirding the administrative state, which conservatives seek to overthrow[2]. Next, I will look at the separation of powers issues raised by Loper (none, to my simple mind). Finally, I’ll look at a few tendentiously selected amicus briefs, and conclude.

The Cause of Action in Loper

Herring, I said. From Harvard’s Environmental Law & Energy Program, “CleanLaw — The Loper Bright Case and Fate of the Chevron Doctrine with Jody Freeman and Andy Mergen“:

[ANDY MERGEN] [Loper] arises under the Magnuson-Stevens Act, an act enacted in 1976, to regulate fishing and federal waters…. The act is a complicated statute. It envisions a role for the regulated community in the development of the regulatory regime, a really unique role, in that fishery councils and there are regional councils for New England, for Alaska, for the Western Pacific, those councils develop the rules, and present them to the federal government, to NOAA, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, and the National Marine Fishery Service [NMFS] an agency within NOAA, to accept the council’s proposal.

The councils’ membership consists of state fishery officials appointed by the governor, and fishermen themselves. They come up with the rules, and present them to the federal government. The federal government makes a decision about them.

This particular regulation relates to observer coverage in the herring fishery in New England. The pursued fish is the Atlantic herring, fish really good for you, not a super important economic fish, but an important one.

So (this is the “jaws and claws” part) who pays for the observer, and how is that decision made?

[ANDY MERGEN] [M]onitoring and observers, the placement of an individual to record the catch and develop information about the catch that the fishermen are taking in, has long been part of the regulatory regime. It actually predates the act. NOAA started using observers in 1972, and there’s no dispute that the statute authorizes the placement of observers in fisheries.

Often, NOAA itself will pay for the observers. In this particular case, what has made this controversial is that the rule requires the fishermen to pay the freight for the observers. The fishermen must have room for the observer on the vessel, and pay costs that are estimated to be around, everyone uses the figure of around $700 a day. That’s somewhat unusual in the sense that often, the agency itself pays the freight on the observers.

Here, the question presented is not whether you can require observers. Plainly, the statute has long contemplated that. The question is, does the statute authorize the council and NMFS to adopt a rule that requires industry to pay for the observers?

The reason why this is a Chevron question, if you will, and why we went into the long description of Chevron is, the statute doesn’t precisely address this question. There’s no specific provision in the law that says, “Yes, industry can be required in some instances to pay for these onboard observers.”

(I highly recommend a full reading of piece, for a real nuts-and-bolts perspective in lay language.) With that, let’s turn to the Chevron Doctrine (“Chevron”)[3].

The Chevron Doctrine and the Administrative State

The Chevron Doctrine was formulated in Chevron U.S.A., Inc. v. NRDC, 467 U.S. 837 (1984) [breaking out calculator, 39 years ago. There’s a good deal of motivated whinging from the usual suspects about how difficult the Chevron Doctrine is, but it seems straightforward enough to me. Chevron is about as close to algorithmic as you can get:

Chevron’s two-step review

The U.S. Supreme Court’s 1984 ruling in Chevron U.S.A., Inc. v. Natural Resources Defense Council, Inc. provided federal courts with the following two-step process for reviewing an agency’s interpretation of a statute:

Step one

A court must determine whether Congress expressed intent in the statute and, if so, whether or not the statute’s intent is ambiguous.

- If the intent of Congress is unambiguous, or clearly stated, then the inquiry must end. Agencies must carry out the clearly expressed intent of Congress.

- If, however, the intent of Congress is unclear, or if the statute lacks direct language on a specific point, then a federal court must decide whether the agency interpretation is based on a permissible construction of the statute—one that is not arbitrary or capricious or obviously contrary to the statute.

Step two

In examining the agency’s reasonable construction, a court must assess whether the decision of Congress to leave an ambiguity, or fail to include express language on a specific point, was done explicitly or implicitly.

- If the decision of Congress was explicit, then the agency’s regulations are binding on federal courts unless those regulations are arbitrary, capricious, or manifestly contrary to statute.

- If the decision of Congress was implicit, then so long as the agency’s interpretation is reasonable, a federal court cannot substitute its own statutory construction superior to the agency’s construction.

Preliminary review: Chevron step zero

In 2001, the U.S. Supreme Court’s ruling in United States v. Mead Corporation narrowed the scope of application for Chevron deference and shed light on a preliminary step in the Chevron process that scholars later described as Chevron step zero. Under Chevron step zero, a federal court asks the initial question of whether or not the Chevron framework applies to the situation. In other words, a federal court must determine whether or not Congress intended for agencies or courts to possess interpretive authority over a statute before embarking on the Chevron two-step process.

Sure, plenty of semantics blah blah blah. That’s why we have legislators (to leave in the requisite “ambiguities”) and regulators (to winkle them out and resolve them), and advocates, too, whether citizens or highly paid lawyers from Alexandria and environs. In this case, I believe that Loper stopped at Step One in the lower courts.

However, judicial deference to agencies’ “reasonable” “constructions” is the space that gives the administrative state room to breathe and live. As the Heritage Foundation, “3 Supreme Court Cases Could Shake Up the Administrative State“:

In practice, Chevron deference enables agencies to often overstep their authority by treating vague language or doubtful gaps in a statute as authorization for actions that the agencies favor but which Congress never intended.

And the Wall Street Journal, “No More Deference to the Administrative State“:

Chevron deference allowed the EPA to set national carbon-dioxide standards, the Transportation Department to prescribe automobile safety features and numerous other agencies and departments to regulate virtually every aspect of American life.

But this approach corroded democratic accountability by freeing lawmakers from the duty to legislate clearly. Chevron also dramatically weakened the judiciary’s ability to check agencies’ regulatory overreach. Before [Chevron], the judiciary took a “hard look” approach in assessing the legality of federal regulations. Chevron was more of a rubber stamp. Judges blessed specific regulations and countenanced agency actions that Congress had never authorized. It made a mockery of Chief Justice John Marshall’s declaration in Marbury v. Madison (1803): “It is emphatically the province and duty of the Judicial Department to say what the law is.”

(I don’t agree that regulations are law, but we’ll get to that.) Or, if you’re really hungry for red meat, Gary S. Lawson, “The Rise and Rise of the Administrative State,” Boston University School of Law, from 1994:

The post-New Deal administrative state is unconstitutional,’ and its validation by the legal system amounts to nothing less than a bloodless constitutional revolution. The original New Dealers were aware, at least to some degree, that their vision of the national government’s proper role and structure could not be squared with the written Constitution: The Administrative Process, James Landis’s classic exposition of the New Deal model of administration, fairly drips with contempt for the idea of a limited national government subject to a formal, tripartite separation of powers. Faced with a choice between the administrative state and the Constitution, the architects of our modern government chose the administrative state, and their choice has stuck.

Just so we’re clear on the stakes.[4]

The Separation of Powers

Some claim that Chevron violates the separation of powers because it encroaches upon the legislative branch. From the Regulatory Review:

[R]ule-making power gives agencies the ability to create secondary legislation. Agency rules should not make primary policy choices. So, when Congress writes statutes in very broad terms, it may not be properly fulfilling its constitutional role.

And from the American Action Forum:

Agencies ask not what Congress has clearly authorized them to do, but what interpretations of statutes could achieve deference and elude courts’ scrutiny. As then-Judge Brett Kavanaugh explained, everything, “unless it is clearly forbidden,” becomes fair game. Agencies risk seizing powers properly understood to belong to the legislative branch, and Chevron deference limits judicial remedies. As Justice Clarence Thomas has noted, Chevron conflates Congress’ neglect to meticulously spell out the precise statutory bounds of an agency’s mandate with an affirmative delegation of expansive authority to the bureaucracy.

Others claim that Chevron encroaches on the judicial branch. Cato:

Chevron is unconstitutional for several reasons. It gives judicial power—the power to interpret the meaning of the law—to the administrative state within the Executive Branch. The Constitution, however, grants all judicial power to the Judicial Branch.

Still others urge that Chevron encroaches on both. Heritage:

To be effective, an agent needs some flexibility to carry out the principal’s commands. But the greater the latitude, the greater the risk that the agent decides to follow his own agenda over the principal’s. The more that agencies reinterpret laws to make room for their own policy judgments, the more agencies appear to act like judges or legislators, though, under the Constitution, they are neither.

In a case so important both doctrinally and to policy — and after decades of collective labor by legal scholars — one would expect conservatives to speak with one voice. Instead, one hears a chorus!

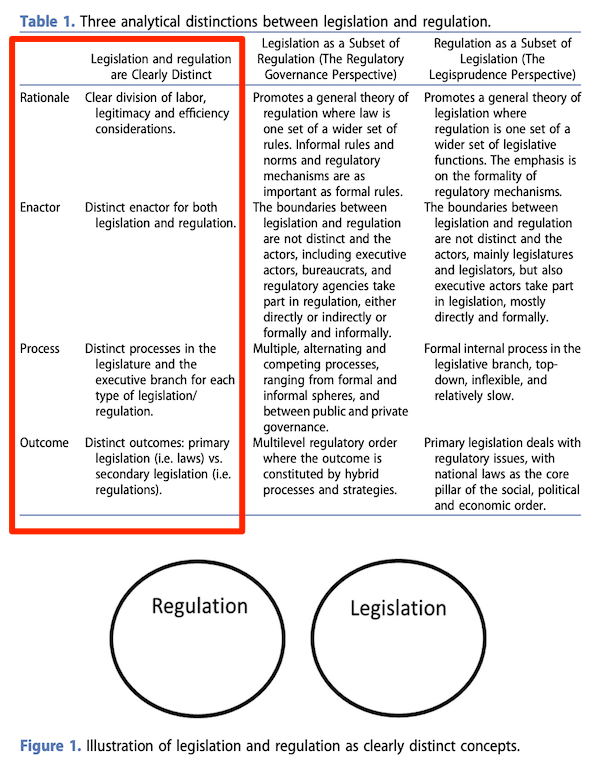

But to my simple mind, the separation of powers concern is the reddest of red herrings. Why? Regulations are not laws! Hence, neither the legislative nor the judicial branches are being encroached upon in the first place. This handy chart from The Theory and Practice of Legislation, “Legislation and regulation: three analytical distinction” (PDF) shows my view, at left, outlined in red:

The simple minds at FindLaw take the same view:

Laws are the products of written statutes, passed by either the U.S. Congress or state legislatures. The legislatures create bills that, when passed by a vote, become statutory law.

Regulations, on the other hand, are standards and rules adopted by administrative agencies that govern how laws will be enforced. So an agency like the SEC can have its own regulations for enforcing major securities laws. For instance, while the Securities and Exchange Act prohibits using insider or nonpublic information to make trades, the SEC can have its own rules on how it will investigate charges of insider trading.

Like laws, regulations are codified and published so that parties are on notice regarding what is and isn’t legal. And regulations often have the same force as laws, since, without them, regulatory agencies wouldn’t be able to enforce laws.

Workers with actual skin the game agree. From Safety Line, “Lone Worker Legislation vs Lone Worker Regulation: What’s the Difference?”

Legislation is synonymous with statutory law; the laws that have been enacted by the legislature as well as those still in the process of being enacted. Legislation is both the description of the legal requirements, and of the punishment for violating the law.

Regulations, by comparison, are the ongoing processes of monitoring and enforcing the law: so not just HOW the legislation is being enforced, but also the very act of enforcement. Where the confusion comes in is that regulation is also the name of the document itself that details the act and description of regulation.

Anybody who has dealt with a legislature and an agency on the same project — as we did, long ago, fighting the landfill — knows in their bones that laws and regulations are not the same. Why, then, do the firms and service providers backing Loper treat them as identical? Leaving aside bad faith, I would speculate that they treat laws and regulations as identical because from their standpoint they are: Both take away their profit (“jaws and claws” once more). But neither voters, nor citizens, nor legislators, nor the courts need to accept that highly motivated view.

Selected Briefs

Finally, I said I’d look at a few of the amicus briefs in Loper. There is, of course, an enormous number (listed here at SCOTUSblog, and hat tip to them for the public service). I needed some selection principle, which in this case was easy. The principle: “Whenever you hear the word ‘Freedom’ it’s some kind of con.” Ditto “America,” “Business,” “Commerce,” etc.; filings encumbered with such verbiage are underlined. Then I eliminated all the filings from trade associations, under the Mandy Rice-Davis (MRD) doctrine; those filings are italicized. Then I eliminated all the think tanks and law firms, also under MRD; in roman. So I’m not going to look at any of these filings:

Advance Colorado Institute, Advancing American Freedom, America First Policy Institute, American Center for Law and Justice, American Cornerstone Institute, American Free Enterprise Chamber of Commerce, American Sustainable Business Council, Buckeye Institute, Businesses for Conservation and Climate Action, Cato Institute, Center for Constitutional Jurisprudence, Chamber of Commerce of the United States of America, Christian Employers Alliance, Competitive Enterprise Institute, Electronic Nicotine Delivery System Industry Stakeholders, FPC Action Foundation and Firearms Policy Coalition, Goldwater Institute, Gun Owners of America, Independent Women’s Law Center, Landmark Legal Foundation, Liberty Justice Center, Main Street Alliance, Manhattan Institute, Mountain States Legal Foundation, National Federation of Independent Business Small Business Legal Center, National Right to Work Legal Defense Foundation, National Sports Shooting Foundation, New England Legal Foundation, Ohio Chamber of Commerce, Pacific Legal Foundation, Relentless, South Carolina Small Business Chamber of Commerce, Southeastern Legal Foundation, Strive Asset Management, TechFreedom, The Foundation for Government Accountability, Third Party Payment Processors Association, and the Washington Legal Foundation.

That list of filers gives a good idea of Loper‘s supporters.

I picked two other briefs to glance at. First, from Public Citizen (PDF):

Congress may legitimately grant agencies discretion to address statutory gaps and to implement broadly worded statutory mandates, consistently with statutory language and structure and the policies they reflect. And “[i]t is quite impossible to achieve predictable (and relatively litigation-free) administration of the vast body of complex laws committed to the charge of executive agencies without the assurance that reviewing courts will accept reasonable and authoritative agency interpretation of ambiguous provisions.” Coeur Alaska, Inc. v. S.E. Alaska Conservation Council, 557 U.S. 261, 296 (2009) (Scalia, J., [Ouch!] concurring in part and in the judgment).

Accordingly, leaving the determination of such details of administration, in the first instance, to the agency charged by Congress with carrying out the statute is not only more workable than letting judges fill in regulatory gaps, but also more consistent with the statutory scheme enacted by Congress. Abandoning Chevron would both fail to yield better results in the run of cases and disregard Congress’s choices to delegate authority to agencies to implement regulatory statutes.

In both litigation and regulation, scientists have a strong interest in assuring that their findings are understood and properly used by others in society, not least by America’s courts of law. For that reason, AAAS submits this amicus brief in support of Respondents.

As the Court recognized in American Electric Power Co. v. Connecticut, “[f ]ederal judges lack the scientific, economic, and technological resources an agency can utilize in coping with issues of this order.” 564 U.S. 410, 428 (2011). They “may not commission scientific studies or convene groups of experts for advice, or issue rules under notice-and-comment procedures inviting input by any interested person, or seek the counsel of regulators in the States where the defendants are located.” Id. Agencies can hear from all concerned stakeholders and elicit expert input, studying an issue—and the various state attempts to resolve an issue—in a way a court cannot. While some study and dialogue arises organically, some was initiated directly by Congress, such as the EPA’s Science Advisory Board, established in 1978 pursuant to the Environmental Research, Development, and Demonstration Act, 42 U.S.C. § 4365. Indeed, Chevron deference is predicated upon the agency’s compilation and analysis of relevant data and its use and explanation of its choice precisely so there can be adequate judicial review.

Conclusion

For the last two briefs, I can only say that I wish all scientists were like aerosol scientists and no agencies were starved for funding or captured MR SUBLIMINAL Isn’t it pretty to think so. Still, it’s always possible to make things worse, and it looks to me like Loper, if indeed it overturns Chevron, would do just that. Imagine, for example, a more dysfunctional CDC. Do we want that? Or a crippled FTC? Or a crippled SEC? I understand the “jaws and claws” crowd disagrees. But firms are hardly part of the Constitutional order. Comments from lawyers — jailhouse and otherwise — very welcome!

NOTES

[1] Without much good reason, I might add. Jodi L. Short, “In Search of the Public Interest,” Yale Journal on Regulation:

This Article seeks to move beyond the rhetoric surrounding regulation in the public interest by conducting a grounded inquiry into how agencies implement public interest standards in the statutes they administer. Using data from agency adjudications under four different statutory schemes dating from the early twentieth century to the present, the study investigates how agencies define the public interest, whether agencies use public interest standards with unfettered discretion based on whatever criteria they wish (as some fear), and whether agencies apply public interest standards in ways that infuse policy making with common good or community values (as some hope).

The study’s findings will surprise many and please few. First, it demonstrates that agencies applying statutory public interest standards exhibit rational and predictable patterns that comport with rule-of-law values of transparency and consistency. Second, the study finds that agencies rarely consider what might be characterized as “common good” or “community” values in their public interest analyses unless such considerations are mandated by statute, and that agencies tend to discount such considerations even when statutorily required. Third, in terms of substantive conceptions of the public interest, the study reveals that in most contexts studied, economic arguments are the most-raised and most-accepted justifications for why a particular outcome is in the public interest.

No problems there!

[2] I paint with too broad a brush, here. After all, overturning the “Chevron Doctrine” is not exactly a small-c conservative thing. (Here is an originalist defense of Chevron). From “Supreme Court To Hear Case Endangering the Chevron Doctrine,” The Regulatory Review:

Over 19,000 judicial opinions cite Chevron, making it one of the most important decisions in federal judicial history. Especially after the Court’s momentous decision to overturn Roe v. Wade, disposing of Chevron would solidify the justices’ willingness to reverse longstanding legal precedent.

The future of Chevron deference also holds considerable political weight. Throughout Chevron’s history, Democrats and Republicans alike have employed the doctrine to defend environmental, labor, and other administrative rules. More often than not, courts have upheld agency interpretations, regardless of the party in power.

In the last six years, however, agencies lost 70 percent of Supreme Court cases addressing Chevron. Instead, the Court has applied a more rigid approach to statutory interpretation, giving agencies less leeway.

Yet leaving the doctrine in place.

[3] Not that I’m cynical, but it occurs to me that the real issue is not the cost of the observer, but the presence of the observer. Overfishing is a thing, and a thing the Magnuson-Stevens and the NMFS attempt to prevent. So this is “jaws and claws” from another angle.

[4] Conservatives off and on the court have a substitute for Chevron lined up, called the “Major Questions Doctrine.” From the Yale Journal of Regulation:

The era of “Chevron deference” will have been displaced by what ought to be called the era of “West Virginia skepticism.” The latter label would refer to West Virginia v. EPA, the decision in which the Court crystallized what has come to be called the “major questions doctrine” (MQD)….

Everybody clear on what “major” means? No?

The West Virginia two-step does not start with the statutory text [(!!)], but rather with an examination of the agency action under challenge. Step One determines whether an agency initiative raises a “major question” as to its legality. The Court has not much clarified how this determination is to be made, and a recent study by Natasha Brunstein of the Institute for Policy Integrity found that lower court “judges have taken vastly different approaches to defining and applying the doctrine—even within the same circuit—illustrating that many judges view the doctrine as little more than a grab bag of factors at their disposal.” Prominent among the common considerations is the “economic and political significance” of the challenged action, although the benchmarks for judging that significance remain unclear. (One disquieting possibility is that contemporary political opponents who lacked sufficient clout to influence the original legislation can now stir up enough protest to activate the “political significance” trigger.)

So, a direct line through the major questions doctrine to the courts via entirely spontaneous citizen action conservative moral panicking and dogpiling, plus the musical stylings of the Mighty Wurlitzer, all funded by the usual suspects, including the Koch Brothers. Handy!

Thank you for putting on your waders yet again. I think you might want to consider first donning a HAZMAT suit and then the yellow waders. This is the Stupidest Timeline, after all, and we all know layered protection is best.

Lambert, thank you for taking a deep dive into the Loper case and the doctrine of Chevron preemption.

While I am no longer an active member of a bar association, in a prior life I was a lawyer, and did work for a federal Judge (albeit not a Supreme Court Justice).

A few observations:

1. Several Justices, most notably Clarence Thomas and Neil Gorsuch, have signaled that they would like to see Chevron reversed or cut back. Over the course of the last 5-7 years litigants have tried to bring cases to the Court that would give the Justices a chance to address Chevron directly or perhaps overrule it. But the Court didn’t decide to take on Chevron directly until Loper came across their transom.

2. It is always speculative to guess why the Supreme Court agrees to hear a case (aka grants a Writ of Certiorari or Cert for short). There are a few things we do know. One is that it takes four votes to grant Cert, meaning at least two justices in addition to Thomas and Gorsuch agreed to hear this case.

3. We also know that this case came through the District of Columbia Circuit where a three-judge panel voted 2-1 and applied the Chevron doctrine and decided that it should defer to the agency’s interpretation. Specifically, The D.C. Court of Appeals concluded that the agency made a reasonable interpretation when it decided that the statute allowed them to charge the company for the on-board monitor.

4. Because the court below ruled in the agency’s favor, the fact that Justice Brown recused herself won’t make a numerical difference. The general rule in the Supreme Court is that, if the Supreme Court is evenly divided, the decision below stands. Thus, it will take at least five votes for the Supreme Court to overrule the D.C. Circuit. If Justice Brown had not recused herself, it would require a 5-4 vote or something more lopsided. Now it will need a 5-3 vote or something more lopsided.

5. We also know from the very helpful ScotusBlog.org website that, when the Supreme Court agreed to hear this decision, the losing side before the D.C. Circuit asked the Supreme Court to answer two questions- one involving the specific statute and one more broadly about whether to overturn the Chevron doctrine. Notably the Supreme Court only granted Cert (aka agreed to hear the case) relating to the Chevron question.

6. One relevant question therefore is: Why did the Supreme take this opportunity to address Chevron when it didn’t agree to take on prior requests to review Chevron. Again, this is speculative. One possible reason is that the change of personnel (namely the addition of Justices Barrett and Kavanaugh) means that there are more receptive voices to overturn or pare back Chevron.

7. I also think there is something specific about this case that makes it an attractive vehicle for examining Chevron, especially if you are a Justice who isn’t enamored with the current state of the law. The last thing Justices try to do is vote for certification (and only four votes are needed) only to lose the decision 5-4 or in this case a 4-4 tie. There is a fair amount of anecdotal evidence that in some cases Justices look for specific facts to make it more likely that they will get the desired result (from their point of view).

8. Here, the nature of the decision made by the administrative agency might be significant. Administrative agencies have issued thousands of decisions over the years about regulations that interpret federal statutes. But in this case, the agency decided to impose direct increased costs. And that is why the facts in Loper raise separation of powers concerns more directly than a vast array of agency decisions. If agencies can directly impose additional costs, does that subvert the role of Congress to do that? That is how Justices like Thomas are likely to see this issue. And that is one reason why I think they are taking this case now.

9. It is likely that Justices Kagan and Sotomayor will not want to overturn Chevron. But they are unlikely to rely on the argument that regulations are not laws. Chevron cases raise the issue of who is entitled to interpret an ambiguous law, and I believe all the Justices will take the position that a regulation promulgated by agency constitutes an interpretation that could in theory create constitutional issues.

10. While the Court has agreed to hear this case, it doesn’t necessarily mean that it will render a sweeping decision. I think justices Thomas might want to strike down Chevron wholesale. But Justice Robers and perhaps others may want to take a more incremental approach. Justice Roberts often tries to get the Court to avoid major doctrinal changes (e.g., he voted to uphold Mississippi’s 15-week abortion ban but didn’t want to overturn Roe v. Wade).

11. This case also raises practical and logistical issues for the Supreme Court. The more sweeping a decision they render relating to overturning Chevron, the more work they create for themselves. If Courts don’t give as much deference to agency interpretations of ambiguous rules, who will decide what the law means? Increasingly the Supreme Court itself. And that would run counter to a decades-long pattern of having the Supreme Court decide fewer decisions in a given term. In the 1970s and 80s, the written decisions were shorter (perhaps because they didn’t have computer software), and the Court issued 150 or more full decisions a year. During Justice Roberts’ tenure as Chief Justice, the Court often publishes something closer to 80-90 full written decisions a year.

12. I suspect that at the end of the day, the Justices will overturn Chevron but not in a sweeping way. I think there are probably five votes for that outcome and the more narrowly drawn the Court’s reasoning the more likely Justice Robers becomes the sixth 6th vote. We will know more when the Court hears oral arguments on this in the next several months. And this is likely to be one of the last decisions it finalizes and makes public when its term ends next June. The courts term begins on the first Monday of October, so there is a long way to go.

Hope this is helpful.

The semantic argument of regulations vs. laws does not work for me. Any rule enacted by an institution of the state requiring citizens or other entities to do something is a law in the purest sense of the word.

Rationale for both are to impose some form of order. Enactor is the state for both. Process doesn’t matter. Outcome matters the most, and it is to impose order and the will of the state in the case of laws and regulations.

And “capitalists” (who generally hate competition, property rights, and free markets) love regulations by the way, because they usually write them.

> And “capitalists” (who generally hate competition, property rights, and free markets) love regulations by the way, because they usually write them.

Indeed … one of my favourite “Not The Onion” headlines (via CNBC):

“Hard lesson for U.S. investors: Chinese companies don’t make the rules in China”

Bonus: check the URL (for the buried lede)!

They love property rights. Just not yours.

They love competition and free markets, from the box seats.

> is a law in the purest sense of the word

Whatever “purest sense of the word” means. If one believes that all exercises of state power are the same, one will be unlikely to succeed in dealing with any particular exercise (assuming the state isn’t completely decrepit).

“We have got onto slippery ice where there is no friction and so in a certain sense the conditions are ideal, but also, just because of that, we are unable to walk. We want to walk so we need friction. Back to the rough ground!” –Ludwig Wittgenstein

> they usually write them

And nothing says that they cannot write them to advantage themselves even more efficiently and faster, which is exactly what the effect of Loper would be. As I wrote in the Conclusion: It’s always possible to make things worse.

As far as I understand, the OP and others it cites appear to treat the word ‘law’ as a synonym of ‘statute’ (something enacted by the legislative branch), whereas their opponents regard it as expressing a broader concept that includes both ‘statutes’ and ‘regulations’. In any case, whether you call regulations ‘laws’ or not, the simple fact remains that the executive needs to be allowed to issue regulations, otherwise government would become impossible.

Your last remark sounds like a product of the usual libertarian mythology. ‘You see, “crony capitalists” actually love socialism. (In spite of what they appear to be lobbying for and doing at every opportunity, they actually love being forced to limit employees’ working hours and to maintain decent labour conditions and being prevented from polluting the environment. They would probably like it even better to just have their property expropriated by the state and to have a communist system instead, but thankfully righteous conservatives are preventing their dastardly Marxist plots to despoil themselves from materialising.) We can tell that crony capitalists love the state, because they do their best to make the state do what they want. Therefore, we should do the exact opposite – we should hate the state and stop trying to make the state do what we want. The state is, by its nature, a weapon of Satan and only Satan can use it; Satanic means can only lead to Satanic ends. If only the state didn’t impose decent labour conditions and limits on working hours and didn’t ban polluting the environment, everything would be great and the holy Free Markets would take hand of everything.’

It’s incredible that anyone can still fall for these twisted and absurd sophisms which are so transparently lab-designed to serve the interests of capital and the moneyed elite. I agree with the OP about most of the passion and energy being on the right – energy comes from resources and the more resources the elite has sucked out of other members of society, the more energy it has to propagate its ideological mind viruses – but I definitely wouldn’t call that energy especially ‘intellectual‘.

Thanks Lambert! A veritable

CorporationsCitizens United Part Deux. Usurping the power of government to function on behalf of the capital holding class instead of the interest of public good is a violent and virulent undertaking. Sadly, a lot of work has been done to ensure that when “public interest” is defined, it really means “what’s good for entrepreneurs”.I don’t see why the Judiciary needs to get involved at all. If Congress feels that an Agency is enacting it’s laws poorly it can pass clarifying legislation.

And of course neither Congress nor the Courts have the staff and expertise to write detailed regulations, which is, of course, the point of Capital’s onslaught against effective regulators.

Which it has. For starters, consider Congress’ emasculation of Glass-Steagall.

I gave this post another round of copy edits. It’s better than ever!

(And check for the “herring” Easter egg :-)

Lambert this is a terrific post and thank you for taking the time and energy to lay all this out so clearly. My initial reaction has been personal – namely that I am growing damn OLD. I had no idea the foundation for this critical case was the 1976 Magnuson Stevens Act. I was a commercial fisherman 1969-1984, east coast, and deeply involved in the fight for the 200 mile limit, fishing on boats that battled the Russians over lobster gear and then meeting with Gerry Studds many times as he worked with Senator Magnuson on the legislation. The act used to be called the Studds Magnuson Act, one legislator and one Senator but then the powerful and rich Alaskan and west coast interests somehow wiped Studds’ name from the act, years ago. (Might have been because he was gay, known in the early 1970s when he ran, and the Massachusetts voters did not care). So I was there, right there, when the law was being crafted, developed, and then later on implemented, during that time in the 1970s when all these environmental laws were passed – Clean Water Act, Clean Air Act, Coastal Zone Management Act, Environmental Policy Act – and each one needed a time of “rule making” translating the language of the legislation into actual things the responsible agency had the power to do to make sure the purpose of the legislation was met. In the case of the 1976 law, it was to rebuild and then maintain the fish stocks which had been decimated by foreign fleets in the 1960s and 1970s. Of course, once we threw out the foreign fleets we built boats of our own, big ones, and easily had and have the capacity to overfish everything – hence all the rules and regulations to limit harvest. Things like giving each boat a set quota of fish to catch, and closing spawning areas, and regulating gear types, and boat size, and fishing seasons, and, as you write about, adding observers. At first the observers were placed on foreign boats fishing in US waters, then placed on the large American factory trawlers, but now, nearly a half century later, it seems even guys running little 40 foot gillnetters in the Gulf of Maine are expected to have people on board. That $ 700 a day is an accounting error on a 260 foot factory vessel, but might be the full day;s profit on that small gillnetter. And, yeah, overfishing is a thing, everyone wants to catch as much as they can, make the most money they can, and its all about somehow balancing that drive to take it all with the need to hold enough back for next year. Those Fishery Management Councils are a unique arrangement and some would argue they don’t work that well, and others that they do, but the whole point was to somehow meld the regulator with the fisherman as a way to build a system that works for all, year after year. I would argue the model has been and continues to be successful. Lambert is in my opinion quite right in the suspicion that all this legal flurry is about those with the capital and power making all the rules and deeply resenting rules and powers that pull away any of their profit.