Yves here. This post provides a much-needed antidote to fixation on green energy wunderwaffen as the way to combat global warming. We’ve stressed the need for radical conservations, as in using a lot less energy in the first place. One approach, particularly in America, is reducing car use. That may not be as radical an idea as it sounds.

By Sarah Wesseler, a writer and editor with more than a decade of experience covering climate change and the built environment. Originally published at Yale Climate Connections

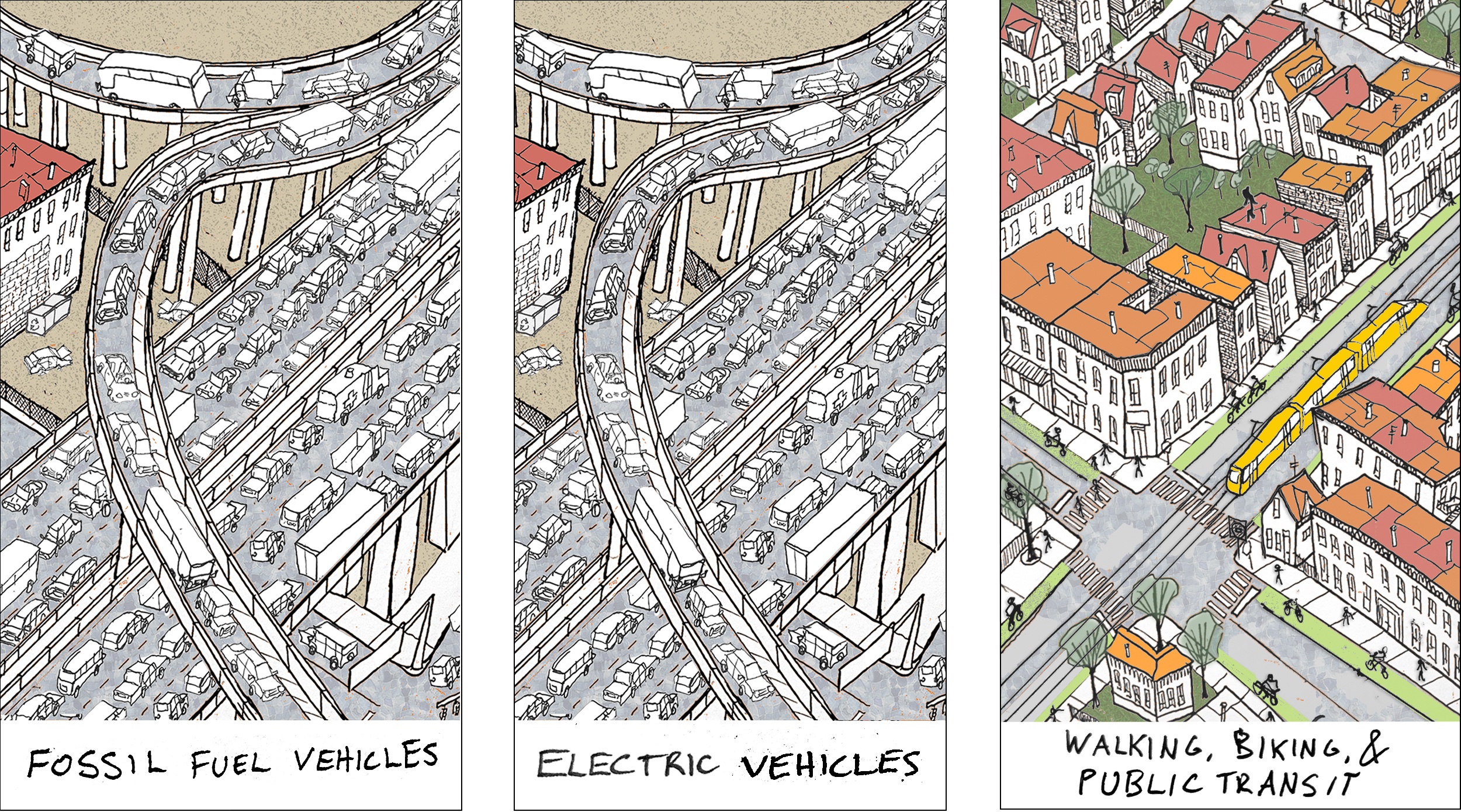

Transportation is the largest source of planet-warming gases in the United States, and passenger vehicles are the top emitters within the sector. To reduce car emissions, authorities ranging from the UN to the U.S. EPA and Department of Transportation say that people need to drive less. But this message is often lost in the excitement over electric vehicles, which overwhelmingly dominate the conversation about decarbonizing ground transportation.

The heavy emphasis on car-based climate solutions seems grounded in the assumption that driving is the only realistic form of transportation in most of the U.S. and that Americans, with their innate love of car culture, wouldn’t have it any other way.

Not everyone agrees with this assessment, however. Increasingly, many policymakers, transportation advocates, and urbanists are making the case that America’s future doesn’t need to be built around the car.

A Radical Revision of City Streets

One prominent skeptic of transportation fixes that rely solely on cars is historian Peter Norton, a professor at the University of Virginia. He has spent years working to understand the role of cars in American society — and pushing back against truisms about the national love affair with automobiles.

Early in his career, Norton’s perspective on the U.S. transportation system was fundamentally shaken by a sentence he came across in a 1920s engineering magazine. “It stopped me in my tracks — it made my pulse race,” he said. “I couldn’t believe what I was reading.”

In the magazine, editor Edward Mehren outlined a proposed remedy for the high numbers of pedestrian fatalities being seen in U.S. cities as cars became more common. Norton can still recite the core of Mehren’s argument today: “The obvious solution … lies only in a radical revision of our conception of what a city street is for.”

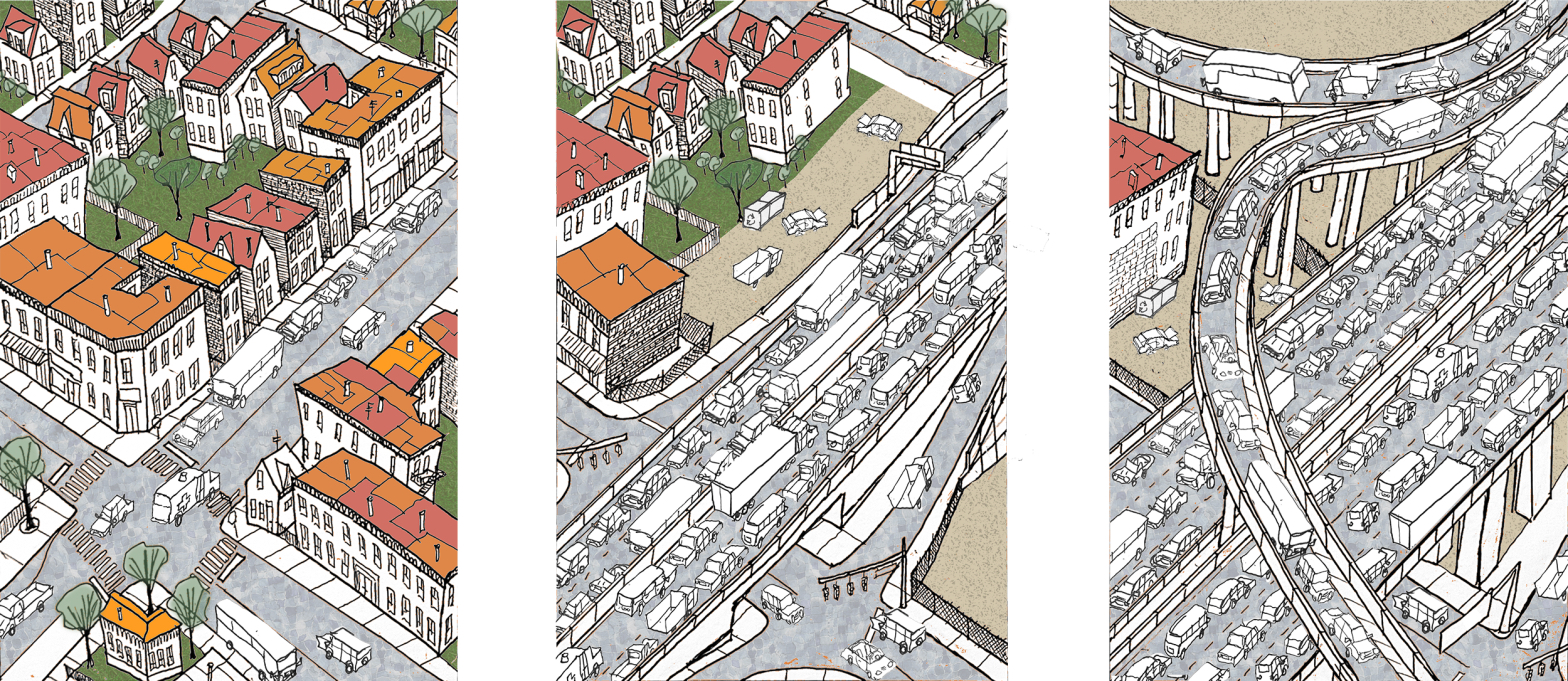

In the early decades of the 20th century, American streets regularly played host to a varied jumble of users, from pedestrians and cyclists to streetcar passengers, frolicking children, and horse-and-buggy drivers. But as more cars entered the picture, their high speeds created new dangers for all present.

Image credit: Antonio Huerta

As Norton documented in his 2008 book “Fighting Traffic: The Dawn of the Motor Age in the American City,” different groups proposed different solutions to this problem. The police focused on developing and enforcing traffic rules, with an emphasis on keeping speeds low to protect pedestrians. Schools started teaching lessons on traffic safety to help children protect themselves on roadways. But Mehren went further, offering a vision of U.S. streets in which cars were the unquestioned principal user.

Before long, this vision had become a reality in much of the nation.

The Myth of America’s Love Affair with Cars

For Norton, Mehren’s Engineering News-Record editorial was an important piece of evidence that the car-centric transportation system now found throughout the U.S. can be traced in part to a deliberate revolution led by a relatively small group of people with a personal stake in the automotive sector. (Mehren himself served as president of the Portland Cement Association, which benefited from the rapid growth of paved roads to facilitate driving.)

The question of how cars came to dominate U.S. transportation is of far more than academic interest. For Norton, lessons from the past offer a useful corrective to the idea that car-centered mobility is the only logical fit for the U.S. History is often used to legitimize the status quo, he said, and the history of transportation is no exception.

“The predominant history tells us that the status quo with car dependency is because that’s what ‘Americans’ — as if that’s a thing — have always wanted,” he said. “And what makes my jaw drop when I look back at the historical record is that that was never true … There was never a moment when lots of Americans weren’t fighting car domination.”

In “Fighting Traffic,” Norton argued that car culture was largely forced on an unwilling public by car dealers, manufacturers, automotive clubs, and others who banded together to promote automobile use, calling themselves “motordom.”

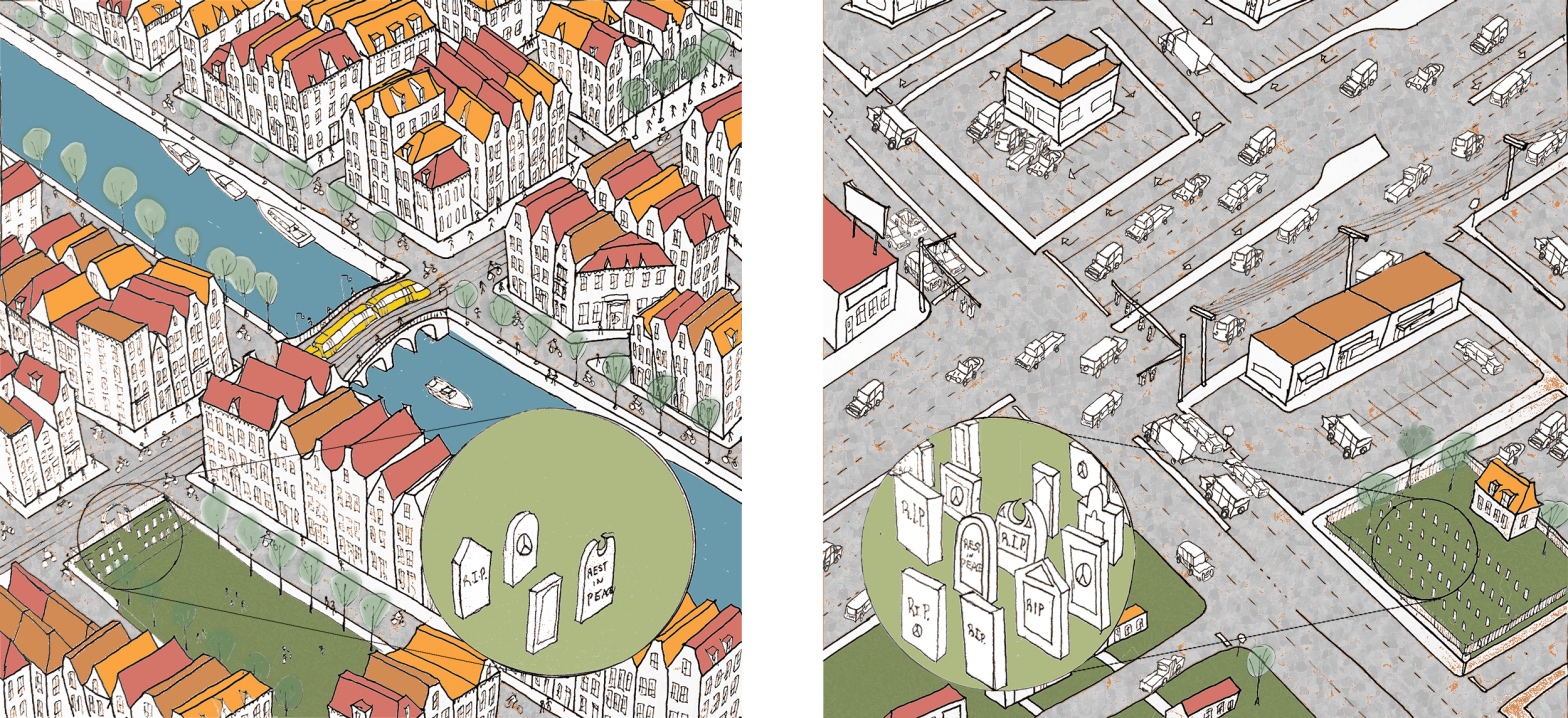

On the other side of the debate, groups including, at various points, the police, pedestrians, women, and business people took action to defend traditional uses of the street. Parents were a particularly key constituency in this group, as many of those killed by cars were children. In 1922, a parade during New York’s “safety week” featured a march by 10,000 children, 1,054 of whom were designated as a “Memorial Division” commemorating the same number of their peers who had died in accidents (mainly traffic) the year before. “White star mothers” — those whose children had perished — were also honored during the parade. Similar events occurred around the country. In 1922, Baltimore held a dedication ceremony for a 25-foot-tall memorial to the 130 children killed in accidents, many involving cars, the year before; that same year, more than 5,000 people attended a Pittsburgh ceremony honoring the 286 local children killed, many of them by cars, in 1921.

The popular discontent shown in these events doesn’t sit well with the narrative that U.S. residents have always embraced car culture. As Norton wrote in “Fighting Traffic,” “Mass demand for automobiles cannot alone explain the automotive city. Even in the United States, there is little evidence in cities in the 1920s of a ‘love affair’ with the automobile … [But] Motordom, far from leaving the future of city transportation to the natural consequences of mass demand for automobiles, fought a strenuous campaign to defend the motoring minority’s legitimacy and to redefine traffic problems.”

Pro-Car Bias

For Norton, the fact that the U.S. transportation sector experienced a dramatic, deliberate shift toward cars in the 20th century offers hope for a second revolution today — one that reduces the primacy of cars in American cities.

“If that sounds far-fetched, that first radical revision was incredibly far-fetched, and it was deeply resisted,” he said. “I think the best thing that we can do to make [a second shift] possible is to recognize that we need it and to recognize that [car dependency] itself is not normal, in the sense that it was the product of a deliberate effort to overturn ‘normal.’”

But recognizing that car-centered transportation is a problem worth solving isn’t always easy. Research led by Ian Walker, an environmental psychologist at Wales’s Swansea University, showed that people in car-heavy nations like the United Kingdom tend to habitually overlook the negative effects of auto-centric transportation. (The peer-reviewed study, which has been published online, is forthcoming in the International Journal of Environment and Health.)

Walker and his co-authors, Alan Tapp and Adrian Davies, developed five statements about driving behavior and risk, then developed a parallel set of statements in which a few words were changed to take cars out of the picture; for example, “There is no point expecting people to drive less, so society just needs to accept any negative consequences it causes” became “There is no point expecting people to drink alcohol less, so society just needs to accept any negative consequences it causes.” They then presented one set of the statements to more than 2,000 adults in the UK and asked them to rank their level of agreement with each; 1,053 randomly selected individuals received the car-based statements, while 1,104 got the non-car version.

When the survey results were calculated, they clearly showed that respondents were much more willing to overlook problems from cars than from other sources. In one case, just 4% of respondents strongly agreed with the statement “People shouldn’t drive in highly populated areas where other people have to breathe the car fumes,” while 48% strongly agreed with its nonautomotive analog, “People shouldn’t smoke in highly populated areas where people have to breathe the cigarette fumes.”

The report’s authors created a term for this pro-car bias: motonormativity. “The way we defined motonormativity in our paper was as a shared automatic assumption that travel is fundamentally a motor activity and must remain that way,” Walker said. Government policies that prioritize EVs at the expense of other low-carbon forms of transportation are clear examples of this kind of bias, he believes.

In the paper, the researchers note that a large-scale transition to EVs would leave many problems related to auto-centric mobility unresolved. They highlight public health as one key area of concern: Car dependency is associated with “an epidemic of physical inactivity,” they write, which significantly increases the risk of cancer, heart disease, diabetes, and strokes, among other health problems.

Car crashes present another pressing public health challenge. Road crashes kill approximately 1.3 million people globally each year, making them the leading cause of death for people aged 5 to 29. In the U.S. alone, 42,916 people died in road deaths in 2021, according to the Department of Transportation. Although this is close to the number killed by guns in the U.S. during the same year (48,830), the issue of systemic car fatalities barely registers in political debates when compared to debates over firearms.

Meanwhile, the average person receives countless messages each day reinforcing motonormativity, Walker said. “Everything from the street designs to the legal system to media reporting to film and television — all of those things push in the same direction of saying that motoring comes first and the harms of motoring are not important.”

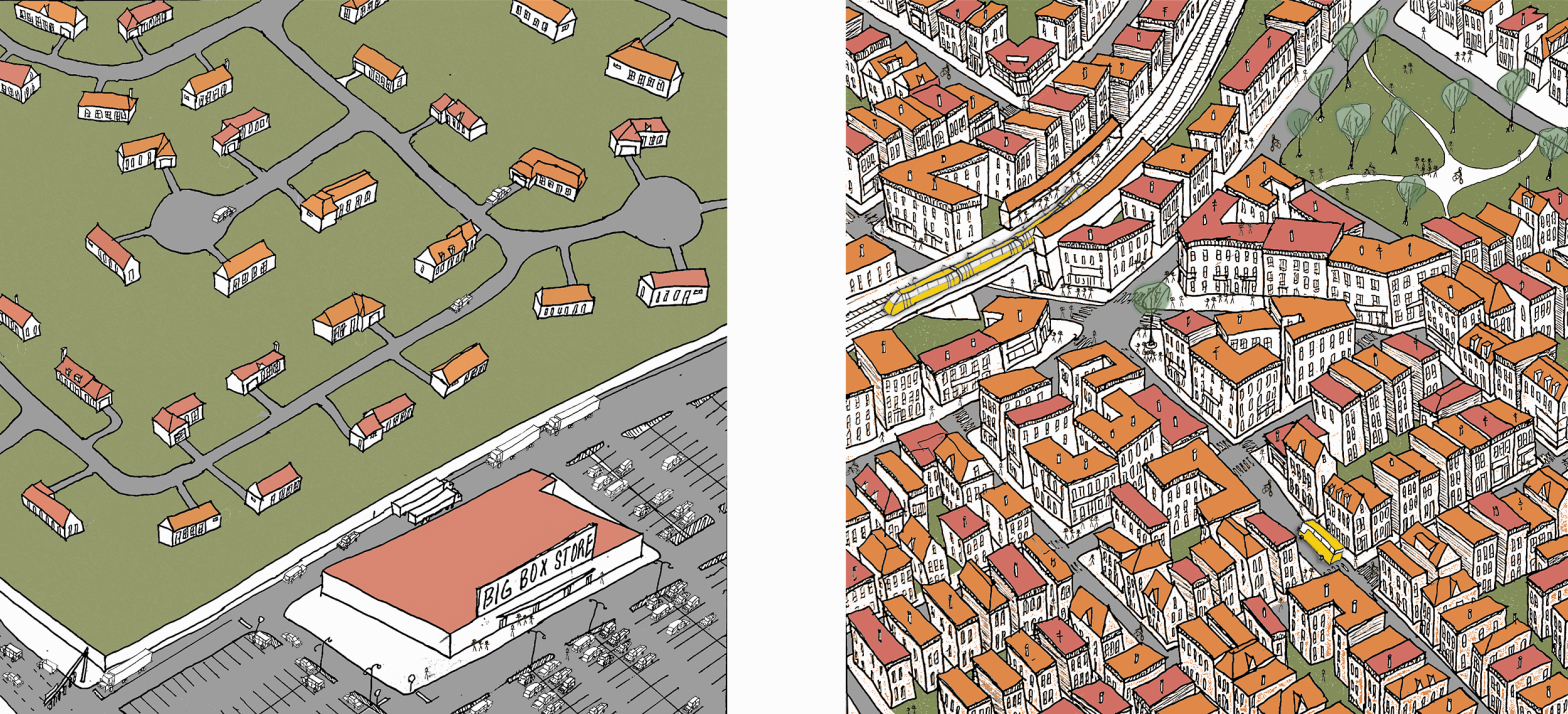

Even less well-understood than the health risks of car-centric transportation may be the fact that, in many ways, it does a poor job of helping people go about their daily business in an efficient, pleasant, and cost-effective manner. Accepting the premise that virtually all adults need two-ton private vehicles to accompany them everywhere they go necessarily implies devoting a vast amount of space exclusively to driving and parking, leading to sprawling, inhospitable concrete landscapes. And when traffic congestion inevitably occurs, the knee-jerk solution — building more roads — often doesn’t work. Through a phenomenon known as induced demand, expanding roads simply attracts more drivers, causing new traffic jams. And as Norton documented in his 2021 book “Autonorama: The Illusory Promise of High-Tech Driving,” there’s good reason to be skeptical of promises that shared, automated vehicles, high-speed car tunnels, or other fixes promoted by the private sector can solve these problems.

Auto-centric transportation is also extremely expensive. According to the U.S. Department of Transportation, the average U.S. household spent $12,295 on transportation in 2022 — more than any expenditure other than housing, with most of these funds going to cars. Vehicle prices are also increasing: Kelley Blue Book, an automotive research company, said that the average price paid for a new car in the U.S. hit an all-time high of $48,000 in 2022.

Building and maintaining the vast infrastructure systems needed to support large-scale car use also consumes massive amounts of resources. In 2019, the U.S. federal government spent $46 billion on highways alone.

A Need for Better Choices

According to Walker, the motonormativity study was motivated by the desire to help individuals grapple with their role in perpetuating car dependency. “The reason we wanted to do it, more than anything, was, what’s the first step in handling addiction? It’s admitting you’ve got a problem,” he said. “And this was intended to get people to ask themselves that question: ‘Do I have a problem here?’”

But the point of helping people recognize their blind spots when it comes to cars isn’t to make them feel guilty about needing to drive — a condition that they probably don’t have the power to change on their own, short of moving to a less car-dependent area. A more productive goal is to help individuals demand more from policymakers and industry, pushing for transportation options that will lead to better outcomes for the planet and people alike.

Fortunately, many government officials are increasingly receptive to this idea, as seen in states like Oregon and California, where agencies are taking steps to make it easier for people to walk, bike, and use public transportation.

“One of the biggest obstacles is the message that people sometimes hear: ‘You need to drive less,’” said Norton. “I think the message that needs to be told is, ‘You need more choices.’ If we could get that message out, and if the public policy could prioritize it, that would really, really help.”

Antonio Huerta is a digital creative engaged in activism for climate change, quality urbanism, and social justice.

The perfect set-up is WFH in the barn with Mr. Ed.

I wish I ‘got’ WFH. I need better coffee.

Kunstler has a great acerbic read on land use planning, development, the auto, and sprawling suburbia in

” The Geography of Nowhere”.

Also good information on historical development patterns in one of the best books I have ever read,

“The Pattern Language”, by Christopher Alexander et al.

WFH=Work From Home.

I’ll add Suburban Nation: The Rise of Sprawl and the Decline of the American Dream by Duany, Speck and Plater-Zyberk.

Duany came to talk to the Folsom planners in 1989 and basically shredded their sprawl plan as the useless tripe it was. Of course the powers that be ignored him and continued to build sprawl.

Nevertheless, Developer (actually “Land Speculator”) Phil Angiledes paid attention noting that pedestrian-friendly mixed-use commands a market premium among buyers and, even though he had the entitlements to build sprawl, he courageously redesigned his Laguna West development using Peter Calthorpe’s “Transit-Oriented Development” (TOD) concept–heavily reliant on building density to provide enough customers for neighborhood commerce and transit. The banks sabotaged the design by refusing to lend construction money for multi-family building. So…what remains is half-assed TOD with three-car garages, without enough people to make either neighborhood commerce or transit economically viable.

The good news is that the State now mandates pedestrian- and bicycle-friendly “Complete Streets” and rather than maximizing auto access, developers have to minimize VMT. I’ve detected not much difference, but at least policymakers are giving lip service to these concepts.

Meanwhile, in England, even small highways have grade-separate footpaths. We USians have a long way to go to catch up with past building practices.

Christopher Alexander’s “Pattern Language” has been adapted by former students to address urban settlement patterns: “A Pattern Language for Growing Regions.” Download a copy or click through to the WIKI. Great visuals to accompany the patterns. Then go out and find them in your own area.

Jeff Speck’s “Walkable City” and ”Walkable City Rules“ add useful info to the topic of reorienting our cities and towns away from cars and trucks and toward people.

Always bemused, however, at all the sites who — like the Pattern Language people here — wish to spark movement toward a better, more sustainable world, yet nevertheless partner with Amazon.

Isn’t that kinda working at cross-purposes? Amazon is a hugely powerful socio-economic actor linked to and benefiting from many of the ugly trends characterizing our present way of life.

</kvetch>

“bank sabotage”…hear him, hear him. A prominent New Urbanist who I met back in the day opined that banks had seven development templates that they would consider development loans on. TOD was not one of them. Prolly still isn’t. No cars? No loan!

Colour me skeptical but this sounds a lot like that ‘You will own nothing and be happy’ work in that it is ALL about inner cities. Nothing about those who live in suburbia much less the countryside. The key here is having people give up their yards and go back to living in apartments again. Trouble is that I would have zero faith in modern developers doing it right like you see in Europe but they would likely be a repeat of similar projects in the 20th century that, through ill-planning and lack of maintenance, turned into high-rise slums. And remind me again what the plans are for poorer people and the homeless are in this set up lest it be turned into a giant gentrification project.

Yes. And there’s another difficulty with the concept. If you look at the various “before” and “after” pictures, you’ll see that a lot of roadway and low-density housing would have to be ripped up and replaced with walkable high-density housing. Unfortunately, we’re already in a housing crisis where we can’t seem to build enough housing of any kind (whether it be low-, medium-, or high-density) and the resulting shortages have pushed housing prices to horrifying highs.

If we start tearing down a bunch of housing because we don’t like the fact that living there requires automobiles, the housing crisis will surely get worse. We’re not remotely prepared to build new high-density “walkable” housing for the 150+ million people who currently need cars for their daily lives.

[And I really don’t care for the idea of pulling people out of rural communities and forcing them into high-density urban housing. Why? Because those “country bumpkins” (with their darned pickup trucks) grow most of our food.]

I know many people prize their lawn, but the truth is that people pay premiums to live in such traditional, transit-friendly neighborhoods, ranging from 40% (like relatively dense Orenco Station in Portland, Kentlands in Maryland) to 600% (Duany-designed Florida development Seaside lots). People love such neighborhoods. And they can be virtually any density. (See here for a diagram). Working neighborhood commerce and transit to which people can walk, however, requires a minimum of 11 dwellings per acre. Duplexes are 10/acre.

The big problem is that the US believes in “rugged individualism,” and configures public policy around that concept. News flash: John Wayne didn’t even sew his own clothes.

Living together requires managing the societal detritus inevitable to large assemblages of humans–things like homelessness, alcoholism, mental illness. The US is singularly unskilled at such management, and if the political right has its way, the immiseration will continue.

We all got the idea that we were English lords and ladies with our manicured lawns.

Poor old Klaus provides a lot of cover for people who are in denial about our society consuming way too much given the size of this planet.

The US, at one time, had the largest passenger train and electric trolley system in the world…all dismantled bit by bit by cities and corporations who bought up the tracks and dismantled them, and encouraged by politicians in the clutches of the auto, rubber and gas corporations. Most people do not want the headache of going into debt to buy a car, getting it registered, getting it insured, keeping it maintained, driving on substandard and dark roads, risking their lives to go from point A to point B. It is absolute nonsense.

Lots of empty lots, extant sewers, and an urban street grid within 5 miles of downtown Detroit or Buffalo. Just look at Google Earth.

neo-urbanists can move there and be the change that they want to see.

No takers for the past 30 years though.

Just saying.

…and yet people pay premiums to live in such neighborhoods where there are jobs and good transit. Never mind property prices in Manhattan, or Hong Kong, I suggest you take a look at Orenco Station in Portland, or Andres Duany’s Kentlands development in Maryland.

After subsidies to the suburbs suck all the life out of civic revenues (and are roughly twice as expensive to maintain as infill) inner cities are, of necessity, underfunded and neglected. The continuing presence of good maintenance, security, clean water (cf. Flint) are all questionable in the areas you mention.

Of course this is a perfect scenario for vulture capitalists to pick up property cheaply, then extort their subsidies for (high end) mixed-use development in those decrepit downtowns. Donald Trump made his fortune, such as it is, taking advantage of the early ’70s period when NY was broke and Gerald Ford refused to bail them out.

Recent HGTV show of people buying mostly very cheap derelict houses in Detroit and fixing them up to sell.

https://www.hgtv.com/shows/bargain-block

Cars aren’t going away, but city centers will likely push to limit congestion like what London has been doing for a while.

I live in the burbs and with most things in the US, our elected officials are delusional in thinking we’re getting rid of cars. We have a local shuttle for anyone wanting a ride to/from shopping, but with the increase in crime, who in their right mind wants to risk that. So no, I’m keeping my car. Since my fellow Angelenos want to keep electing the dregs of society to mooch off the public teet while blowing off their job, I have no interest in taking the risk. My family’s safety will always trump whatever word salad rationale they mime. Maybe if they did their job I wouldn’t feel this way, but if the queen had balls, she’d be the king.

I’ve come to the conclusion too many highly educated don’t know how things work. All ideas are considered in isolation from other competing claims or ideas. “Woke” is the most flamboyant example of this bubble-world think.

For an example: everyone in my area is thrill ed da new car and light equipment lithium battery manufacturing plant is opening. EV’s! Green New Deal! Jobs! did I mention Jobs?! Great, I’m for it. However, our current electricity grid and power production can’t produce enough new capacity to power this manufacturing facility right now without bringing back online a coal-fired power plant that’s been offline for a few years. OK, makes sense to me. However, the local virtue signalers are furious the coal-fired plant (bad!) is being brought back online to power – at least for a time – the power needs of the new Green battery (good!) production facility.

Like I said, a lot of these highly educated folks have no idea how things actually work, how they are interrelated and interconnected. / meh

“All ideas are considered in isolation from other competing claims or ideas.”

Yes! This is definitely a problem with a significant portion of our “elite” population (whether activists, academics, politicians, members of the media, etc.), and it seems to be getting worse with time. Now there are obviously people out there who are capable of “seeing the big picture” and evaluating the real-world trade-offs that would occur if certain changes were made, but their voices seem to get drowned out by the voices of those who “have no idea how things actually work.”

It results in an awful lot of noise, and it occasionally results in policymakers pursuing changes that are certain to fail and cause a lot of disruption before the failure is ultimately recognized.

The issue I see with your framing here is that ‘how things work’ ultimately is still a choice, preference, decision et all.

I don’t have any illusion that utopia awaits by significantly shifting towards organizing societies differently but it’s apparent that the structures of ‘how things work’ is fraying at the seams and there’s this trend of trying to go around the issues or just flat out doubling down.

I live in a predominately rural area and I know what a lift it’d be to reorganize transportation infrastructure to accommadate rural residents as to not leave them abandoned. On the other hand, attempting to maintain this status quo until the tide comes is not tenable but I fear that’s the likely outcome.

Yep, it’s “how things work” that have brought us to the edge of the cliff.

Poor old Klaus ends up being cover for a lot of denial of the seriousness of our situation.

Bring back industrial manufacturing, with large scale industries in specific locations – think Detroit and Pittsburg back in the day – and people will flock to places with jobs, and public transportation will again be a thing.

Until then, with people driving long distances to scattered jobs or gig jobs, good luck with making the US not car-centric.

So, I work in a field classified as ‘light industry’. When I entered it 25 years ago there were probably 40-50 employers of various sizes in this field in the core city area; I am guessing there are maybe a dozen now. Lots of reasons for this, upshot though is the employers who can afford to pay me are now all located in the suburbs, where there is room for the giant footprint needed for their equipment and warehouses.

Now, when I bought my house, I was working in the city, didn’t have a car, and purchased where I did because all essential services (groceries, pharmacy, good coffee, good weekend breakfast, etc.) were maybe 10 minutes away on foot or by bus.

Then there was a job change, and another, and now my office is 45 minutes away by car with no bus service that far out (and the people who live out there really like it that way). COVID saved me from that commute as my employer seems to have been one of the few afterward to have decided that butts in seats wasn’t worth the cost of the extra building they needed to lease just for the office staff. Otherwise, my choice would be to keep the car or move and still keep the car because again, what I do is now done in the suburbs.

So yes, please, let’s find ways to bring industry back to the core Midwestern cities, one of which will, I think, mean finding ways to do industry in smaller spaces.

The idea is great. It is also putting me–voluntarily–out of business: I’ve worked as a semi-pro musician for many years. I carry a lot of stuff: instrument, amp, speaker cabinet, mic stand, various electronic doo-dads. Until very recently, most of my work took place on weekends at venues at least an hour (by car) from home. I’ve finally had it with the commute. I’d like to keep working, if only I didn’t have to log so many hours on I-91. And if I-91 weren’t so plagued by “freedom-loving” drivers who express their daily frustrations with life by driving like maniacs.

From the EPA website;

“The largest sources of transportation-related greenhouse gas emissions include passenger cars, medium- and heavy-duty trucks, and light-duty trucks, including sport utility vehicles, pickup trucks, and minivans. These sources account for over half of the emissions from the transportation sector. The remaining greenhouse gas emissions from the transportation sector come from other modes of transportation, including commercial aircraft, ships, boats, and trains, as well as pipelines and lubricants.”

Transportation is the largest source of emissions (31%). However, only half (at most) are from passenger vehicles. All of the actions in this article will;

1. take decades to have any impact, and

2. will only make a dent in the half of passenger vehicle emissions.

doesn’t make them a bad idea, but they are not a panacea

Thanks for unveiling the big picture. How about shrinking our military footprint (and a few others).

I am in Sicily the last 10 days and people here love their cars like everywhere else on the planet. It’s freedom and control. Let’s reinvigorate our small towns and spread out the population before densifying further as a textbook solution.

Because “freedom fries” and markets, one trick pony America will have a car centric public transportation system for a while longer. Then I suspect it will have extraordinarily wide bicycle paths. The EV unicorn fairy will end up being the EV bike, if we’re lucky.

We could be building out a comprehensive and varied public transportation system, like the Chinese, but that would be too smart for Mr. Market.

Shame.

I just used my “Edit: Find in Page” function and entered the word “military” into the box. No hits.

Nothing.

No one with even a cursory idea of the overall pollution menace would do a write-up that doesn’t include the United States military. Hell, an argument can be made that the conversation should begin and end here.

Instead, the little people are again at fault.

Peoples cars?!

https://duckduckgo.com/?q=us+military+biggest+emissions+&ia=web

Shame.

Don’t you think things are a bit past the whataboutism stage? Yes, the military contribution to environmental destruction is abominable, but it will also be necessary to bring an end to Happy Motoring. It’s an “all of the above” situation at this point.

Thank you Melissa! Along with earl’s comment above, this is I believe the correct context in which to view attempts to green-up transportation, along with an eye to the geopolitical implications of the specific resources necessary, and the industrial requirements and social effects of individual cars vs. mass transit.

Yes, I think we should drive less; I also think we shouldn’t have an empire overthrowing popular governments in the ‘lithium triangle’ whenever necessary to make sure folks can buy a new EV every few years.

I tried to get into land development and my observations haven’t changed much.

I live in an old streetcar suburb in Charlotte. The land practically screams for urbanism. Yet for year after year, the city said ‘It’s a single family neighborhood’. I couldn’t be bothered with going through the rezoning process.

So I watch multiple time as old houses are torn down and replaced with McMansions.

I saw a beautiful corner lot that would of made a great site for five townhouses. No, no, no says the city. So a 1.2$ million dollar home goes up. No rezoning required.

A home builder recently tore down an old duplex, bought the neighboring corner lot and replaced it a single duplex. So even less density now.

This housing bubble combined with terrible zoning policies are crippling cities. I see social stagnation and conflict arising from this for years.

Mutiply this phenomenon with every neighborhood in the area. It’s pushed some of my views really far left.

To paraphrase Jane Jacobs’ Life and Death of the Great American City: Modern planning is positively neurotic in its willingness to embrace what doesn’t work and ignore what does…It’s an advanced superstition, roughly like 19th century medicine when Doctors believed bleeding patients would cure them.

…

My 2¢:

The city of Houston literally has only minimum lot sizes and road standards. Zero “planning.” If your subdivision private restrictions don’t forbid it, you can open a commercial bar in your residential neighborhood living room.

I would defy anyone to detect a significant design difference between Houston and any sprawl city. “But what about that Houston flooding in Katrina times?”… The Sacramento Region is replete with the racket called “planning” and is second only to New Orleans in flood risk. It’s a racket. Period.

That’s the problem with HOA’s though. Naturally more wealthy enclaves will be ready to defend their restrictive covenants to the death. If they don’t and forget and let a duplex be built without filing a suit, the covenant is cancelled.

Land developers are given a big tip to stay away from wealthy enclaves as they will be litigious. The neighborhood I grew up in for example. 50′ front setbacks to maintain ‘neighborhood character’. Easily fit a house in that setback.

It’s Life in the Jungle, Nature red in tooth and claw. Riches don’t want to live next to Poors (often conveniently identified by skin color), and vice versa. If only the West had a political party that represented the rights of the Poors…

When we lived in England, my wife & I didn’t have a car. We went from Liverpool to London quite often, always by train.

One day we went to London with a friend, who wanted to take her car. We were astonished at how cheap the trip was. The gas cost less than one train ticket (and gas in Europe is expensive). Her car was an old beater, which had cost her very little.

So while these are good ideas, for them to work it will be necessary to rethink public transport and its currently exhorbitant costs. In the UK and Europe, that will mean renationalizing the railways and buses, and introducing price controls.

Agreed, neolibral privatization of the commons needs to go. Free/highly subsidized public transport has been tried in a few places recently with decent (not flawless) results. Free municipal transport is a fraction of base infrastructure construction and maintenance costs.

Spending a week in the Netherlands tends to opens minds on the safety and effectiveness of bicycles as legitimate transportation.

To the skeptical…don’t let the comfort of status quo close your mind. There are win win win solutions out there. More options/carrots less mandates are the way. Cars are great but not for everyone, the lack of viable alternatives in the US is sufficating. Rural/suburban lifestyles are currently subsidized beyond the cost of free buses or safe bike paths and pubilc funding drives behavior. Change is slow but small adjustments can snowball into new urban landscapes as people see and experience quality of life improvements. Opposing urban transport projects because you’re pro car is as unproductive as punishing drivers with taxes or forcing EVs. The intangibles of getting out of a vehicle has wide ranging mental, physical and societal benefits not easily explained or invisioned yet convincingly felt. Happy people with affordable life options make better safer civilizations.

That is hoq it is in Germany aa well

As I live in a very rural area, I’m pretty pro car, which is different from the majority here, but in the near future I’d expect that the opposite will happen.

Fewer Americans are going to want to live in the urban areas after the pandemic.

https://www.pewresearch.org/social-trends/2021/12/16/americans-are-less-likely-than-before-covid-19-to-want-to-live-in-cities-more-likely-to-prefer-suburbs

Among white collar workers, although there has been a push back to the office, hybrid work has become the new normal.

The general public wants space – having their own backyard and a larger home. That’s only possible with lower population densities facilitated by the automotive sector.

While I agree with the conclusion that the public rather than the pirvtae sector or rich people should drive conclusions and that the US should be more involved in manufacturing, a genuinely democratic society in the US would be one that be one where the suburbs and rural voters outnumber the urban downtown core voters, which are seeing their population decline.

In addition, the article doesn’t discuss how although automobile ownership is costly, living in denser areas tends cost more per square foot or meter. Apartments are more costly and that more than offsets the cost. Hence, why the urban cores of cities such as New York City, which is probably the most close city to what the article wants, has a reputation for being a high cost of living city.

http://www.newgeography.com/files/fanis-housing-3.jpg

This statement: “The general public wants space” is B.S. Consistent with Brandolini’s law, it takes orders of magnitude more energy to debunk than to create.

If the “public” is so averse to living in urban areas, why are big city prices for real estate so high? San Francisco, Hong Kong, Manhattan, etc. all contradict this assumption. Someone not only *desires* to live there–and talk is cheap–they spend their money, paying a premium, to do that. Urban living is about as costly as suburban living with mandatory car ownership, too, even if the property prices are higher. Transportation costs less in cities and has lower environmental impact when transit is available.

Cities bring other problems, but not the ones you think. For example crime per capita is higher in (sprawling) Phoenix AZ than in NYC. Services for the unhoused, the mentally ill, etc. are not optional in higher densities. Naturally this is what the US underfunds, so misery abounds.

One thing not mentioned in the article: the “tax” of having to own a car is one of the most regressive, keeping the poor poor since every driving age adult must own a car in sprawl. Children and the elderly are relegated to being chauffeured by Mom or elder warehouses where the last of an old person’s fortune is sucked out of their bank account. No possibility of aging in place–the overwhelming preference of those who age out of driving.

Incidentally, take a look at the New Urbanist Transect. All densities, from farms to dense downtowns can work. No need to feel you’re trapped into doing urban living. Of course, if you’re lucky, you’ll live long enough to be unable to drive. Then you’ll pray for traditional neighborhoods where you can walk to shopping or parks for those elder years.

One big problem avoided: seniors on the road, if you have working transit (and you need enough riders within a walk of the stops to have that). The fastest growing demographic: over 85 years old.

The polling data clearly indicates that a clear majority of Americans have a preference for living in lower population density areas. Americans also have negative perceptions of dense urban areas.

https://today.yougov.com/politics/articles/42102-high-density-worse-environment-traffic-and-crime

https://www.pewresearch.org/short-reads/2023/08/02/majority-of-americans-prefer-a-community-with-big-houses-even-if-local-amenities-are-farther-away/

The same is also among young people ,a demographic that pre-pandemic, was associated with urbanism.

https://www.redfin.com/news/millennial-homebuyers-prefer-single-family-homes/

In fact, even before the pandemic, Generation Y was leaving the large US cities for suburban areas.

https://www.cnbc.com/2019/09/29/millennials-are-fleeing-big-cities-for-the-suburbs.html

So no, it’s perfectly rational to state that there’s a clear preference for suburban single family housing among Americans.

If the US is to be a democracy, then the policy will be set by the majority of Americans, rather than say, a small minority, whether they be rich people, the upper middle class / PMC (effectively an aristocracy), or the urban planning profession.

An increase in urban density by 1%, on average, increases wages by 4%, whereas housing costs go up by 19% and 21% for renters.

https://tomorrow.city/a/the-cost-of-high-density

In regards to why housing costs are costly in cities such as Hong Kong, San Francisco, part of the reason is because of land. Hong Kong is on an island and San Francisco is on a peninsula. What’s driving this is a large amount highly paid employees in industries like finance and technology, along with the costs of high density as stated earlier.;

San Francisco at time of this writing is actually seeing its housing costs decline, so I’m not as sure that is going to be valid and indeed, the city is in danger of facing the same fate as many of the Midwestern cities hurt by free trade. Manhattan too appears to be a city that is in a state of decline and NY state recently lost a Congress seat.

In regards to NY, here:

https://finance.yahoo.com/news/york-city-lost-5-3-100000482.html

Does that mean New York is doomed? Nope. But does it mean that the city and state will play a smaller role in the US as a whole, having lost population?

Certainly, the city will recover from the rock bottom (as testified here):

https://www.nakedcapitalism.com/2020/06/some-thoughts-on-new-york-city-and-the-dim-prospects-for-american-cities.html

But it will not be the world of 2019. It will however be a world where the cities like NYC play a smaller role in governing the US and the suburbs / exurbs / rural areas play a larger one, simply because they have a larger percentage of the population.

It looks like my comment earlier vanished. Take a look at the polling data. There’s a clear preference for rural areas. The source of this is from a Gallup poll.

https://arc-anglerfish-washpost-prod-washpost.s3.amazonaws.com/public/LBTRQFSYSZAQ7DZ6K5AOOVEP6E.png

There’s a clear public preference for lower density and American public opinion has a negative association with urbanism.

https://today.yougov.com/politics/articles/42102-high-density-worse-environment-traffic-and-crime

The polls show the American people do clearly prefer space with lower population density.

As far as why cities are costly, that’s a function of high density resulting in wages growing slower than housing costs, limited land (San Francisco is a peninsula, where as Hong Kong and New York are on islands) and a large number of highly paid individuals in Finance and Technology.

There are of course, very expensive suburbs too where highly paid professionals exist, but not quite as expensive, owing to the lower density.

Currently, San Francisco is seeing a decline, as is NYC in population.

Kurt Vonnegut was all over this 50 years ago in “Breakfast of Champions”, about a science fiction writer whose most popular book was named “Plague on Wheels,” which described

“life on a dying planet named Lingo-Three, whose inhabitants resembled American automobiles. They had wheels. They were powered by internal combustion engines. They ate fossil fuels. They weren’t manufactured, though. They reproduced. They laid eggs containing baby automobiles, and the babies matured in pools of oil drained from adult crankcases. Lingo-Three was visited by space-travelers, who learned that the creatures were becoming extinct for this reason: they had destroyed their planet’s resources, including its atmosphere. The space-travelers weren’t able to offer much in the way of material assistance.”

Car person from Michigan:

Cars made you “not poor”. You could do something with cars in MIchigan & have a middle class life. This dating back to the beginning of cars.

Then, name me something that is produced by the economy that creates more economic value that automobile production. It takes cheap raw materials, labor, and capital, and produces 16 million $48,000 cars per year ($768bn). You can argue airplanes, or the military. But their customers are limited. Anyone can buy a car. Anyone can sell cars. Anyone can make cars.

Cars took over mostly rural Michigan, Ohio, Illinois, Indiana and turned cheap, worthless farmland into factories and turned farmers into factory workers (who then built the UAW).

What do you replace a trillion dollars of auto economic activity with? Not saying you shouldn’t, just throwing out things we have to consider. Personally, i would argue to convert all those factories to building space shuttles & rockets & such. But those r a niche product right now & would not have the “on the ground” visible results (I built that car you are driving).

And think of poor John D. Rockefeller & Standard Oil! What will his decedents do without all those cars buying oil & gasoline? Rockets use hydrogen & oxygen.

This mistakes the symbols of wealth for actual wealth. The diversity of species on that “worthless farmland” may prove more valuable than what (eventually) ends up rusting in some junkyard.

Mistaking “economic activity” for wealth is so common that Alfred North Whitehead called this kind of thinking the “fallacy of misplaced concreteness.” Imaging going to a restaurant and devouring the (paper) menu.

Another name for it: “Midas disease.” A bigger plague than COVID, if you ask me.

The ten commandments call giving one’s devotion to a symbol rather than the genuine article “idolatry.”

A job guarantee could handle the transition away from our current extractive industries, at least in part. You can be sure that the transition is inevitable, too. Mother Nature always has the last word. Odds are we’ll avoid the simple solutions rather than engaging in the most difficult of tasks: changing our minds…so there’s that.

Well, my lifetime will likely bookend the “car-opia” era in the US. Grew up in San Francisco when there were no freeways; most families had one car and many used the trolleys to get around. Getting to Yosemite took all day, with not a freeway in sight. Max speed limit on the highway was 45MPH. Gasoline was 25cents/gal. (19cents during Gas(station) Wars). The post-War(II) growth of industry and income for America led to bigger families and bigger houses in the borderlands (Ukraine?).

The freeway construction began mid-50’s and satisfied both suburban housing and potential military transport. The freeways were designed for 65MPH and the car industry satisfied consumers with fast gas guzzlers amenable to the freeway design and cheap gasoline. As the urban areas became congested with cars, air pollution made living there hazardous. More people to the suburbs. More people driving cars. Eventually even the freeways became congested during Rush Hour.

Imminently the California air resources control board mandated cleaner engines. Most auto manufacturers complied and the price of cars went up. Higher travel speeds led to more fatal crashes and insurance coverage became mandatory and expensive.

Today we have freeways that are worn out and their general maintenance slows travel speeds to 25MPH , or less. Gasoline is now $6/gal. and everyone buys EV’s to travel in the fast carpool lanes. Driving a car has become very expensive.

Thank you for this. Every time the EV discussion comes up, I either think or express my frustration with the dialog. My diatribes on “walkable communities” virtually always fall on deaf ears, or else are met with canards and gotchas like “what about elderly people who can’t walk?”

I think unfortunately this is one problem that will only be addressable with outright and total fall of the American government, as so many problems are.

A lot of skepticism about this in the comments today and me too. I’d say the appeal of car culture is a way more tangled topic than the simplistic “people were talked into it.” And now that we have car culture not having it is also complicated and, as we are seeing, even daunting.

It’s not like people haven’t been making these criticisms for a long time and well before global warming became a prime topic. On a personal level I’ve had spells where I barely drove a car at all. The result was I blew out my knees with so much bike riding (although all better now–I walk a lot instead). In a young, fit society ideas on paper may sound perfectly sensible. America is often, increasingly often, not that.

https://www.construction-physics.com/p/how-fast-can-a-city-grow

The above from this excellent site talks about how Los Angeles suburbanized before cars were even much of a factor. In this chicken and egg discussion the impulse to spread out was always there and then came the means.

Big crowded cities are hardly Eden and have many of their own sets of problems. Meanwhile in a late 19th century America, where most were still farmers, cars were a huge boon. The way Americans live is a product of circumstances, not big business propaganda although without a doubt that is a factor.

I grew up in the suburbs. I commuted by personal motorcar 75 miles round-trip every working day for 34 years.

I am now spending my well-earned retirement in the countryside, where I can live at arms-length from the petty human conflicts that I spent my working life mediating. I must happily drive a mile to the paved county road and another five miles to town for victuals. Today I traveled 150 miles round-trip to look at trees for my orchard and garden at multiple tree nurseries.

Perhaps I live a privileged life, but I’m grateful for my 2 cars and my pickup truck. I’d hate life in a crowded city, even if the pavements were reserved for flaneurs and break-dancing. From where I sit, the problem is too many humans. Traffic is but a symptom of their pestilence, not it’s cause.

Again, like the battery electric vehicle article, an article that focuses on a pseudo-problem and pseudo-solution that nobody could object to but will never happen rather than the real problem and the unpalatable but certain solution: raise the cost of energy with energy taxes and of land with a land value tax, ban greenfield development and spend the money on public transport and, in the interests of fairness, a compensation fund to buy out stranded exurbs (and either densify them or raze them) and to subsidise rents for the poor. Inner suburbs will see soaring land prices but the land value tax will recapture these and motivate plot subdivision or gentrification.

American “suburban” living, in the sense of wanting gargantuan single family homes with the benefits of the city without the costs, is unsustainable with expensive energy and land. Heating large houses, driving long distances, paying extra costs embedded in labour and freight on all goods and services and local taxes etc. Developers would soon switch to densification and the local governments they co-opt would soon switch to supporting them. Running high speed bus lines (like Curitiba in Brazil) on existing road infrastructure could be done overnight and tram and rail lines could subsequently be developed on the highest ridership routes.

This article puts the cart before the horse. The car-suburb is simply the symptom of two economic drivers, cheap land and cheap energy. Fussing over walkable cities is like trying to cure obesity by insisting everybody uses smaller plates and eats with cutlery like Europeans do, when the problem is cheap grain-derived calories.

But this it is never going to happen because the American dream is built implicitly on cheap energy and explicitly on cheap land (and continual expansion into virgin territory, so that failures can be left behind rather than fixed and one needs never “cultiver son jardin”).

The wholesale re-architecting of the US city cannot be achieved as a goal in itself, only as the side effect of a radical change in the boundary conditions of US life. That is how it was achieved in the first place. It is likely that, given the incentives, even if urban planning had retained pedestrian primacy and tamed the motor car in city centres, suburbs would have been invented anyway, in reaction to the strictures, with freeways connecting them and depositing their occupants into congested towns.

On a separate point, the research described, of offering people statements about negative externalities of smoking and of car use, is ridiculous. Perhaps the actual research was better than described but on what is presented, the method is clearly flawed. Only a minority of people smoke, the majority view will be for control of something that inconveniences them. A majority of people drive or realise that they depend daily upon driving for their material wellbeing, so they will not justify any controls on driving because its costs are largely externalised and the private benefits immense. This does not mean people give driving a free pass, it means that people value their best lives and that in today’s world, includes driving but not smoking.

There’s no great surprise in this result, the only surprise is the fact somebody bothered to run a halfarsed experiment to validate it, which suggests that these planning policy researchers have no idea what actual people want or need or how they reason!

Have you ever seen a horse take a piss? I grew up in a city where there were still some horses like those used by the police. My grandparents knew when there were hundreds, if not thousands, of horses in the city. If you think about the piss and horse shit, which was a full time job to collect, together with the smell and flies, you might easily imagine that the auto was once welcomed as a healthy alternative to horses.

Another fact from Inc., and other sources, is that 10% of Americans consume 50% of the alcohol, and 20%-30% drink 70%-80% of it. Thus, when talking death and destruction on the road, alcohol and drug use, no doubt, play a role.

Cars were once the solution but times change and they became the problem. The dangers from leaded gasoline and subsequent coverup was a major scandal. Cars are also inefficient as in nearly all the fuel is needed just to move the car itself. We already have an efficient electric transportation system called trains and service can and should be vastly improved.

Redesigning large and small cities in order to minimize the use of autos should not be difficult and, no doubt, would make life better for everyone.

When I see the images on the right, with stacked living, it reminds me of the time I lived in a towering twenty six story hovel over run with cockroaches.

I sold my car in 2010 and have definitely diverged from all the people who take driving for granted. The ‘get distracted for more than three seconds and you’ll die’ part really stands out for me whenever I do drive now. Biking is so much more laid back, and the parking is fantastic.

Don’t forget parking spaces. Here in the USA we now have more than 2 billion parking spaces. The city council where I live has a big fight every few years about adding more parking space. And yes it’s paid for by government. We built a $16000000 parking garage using city, state and federal money to accommodate the plethora of restaurants and tourists.

Singapore charges a heavy fee just to get a permit to own a car. then come the costs of buying the car, registration etc. For a entry level car the fee is USD 75000 and it goes up from there.

Of course USA is not a city state. Never the less this model could be adopted by large cities around the world .