Yves here. Richard Murphy provides a fine takedown of the pernicious role neoclassical economists have played by overstating the risk of inflation and using it as a pretext to cruch wages. However, Murphy, no doubt due to space constraints, understates the scope and nature of damage done by neoclassical economics, which has become the foundation of mainstream thinking, Neoclassical economics tells a huge lie, that economies have a natural propensity to arrive at stability and full employment. As we wrote in ECONNED:

In 1776, Adam Smith published The Wealth of Nations. In it, he argued that the uncoordinated actions of large numbers of individuals, each acting out of self-interest, sometimes produced, as if by “an invisible hand,” results that were beneficial to broader society. Smith also pointed out that self-interested actions frequently led to injustice or even ruin. He fiercely criticized both how employers colluded with each other to keep wages low, as well as the “savage injustice” that European mercantilist interests had “commit[ted] with impunity” in colonies in Asia and the Americas.

Smith’s ideas were cherry-picked and turned into a simplistic ideology that now dominates university economics departments. This theory proclaims that the “invisible hand” ensures that economic self-interest will always lead to the best outcomes imaginable. It follows that any restrictions on the profit-seeking activities of individuals and corporations interfere with this invisible hand, and therefore are “inefficient” and nonsensical.

According to this line of thinking, individuals have perfect knowledge both of what they want and of everything happening in the world at large, and so they pass their lives making intelligent decisions. Prices may change in ways that appear random, but this randomness follows predictable, unchanging rules and is never violently chaotic. It is therefore possible for corporations to use clever techniques and systems to reduce or even eliminate the risks associated with their business. The result is a stable, productive economy that represents the

apex of civilization.This heartwarming picture airbrushes out nearly all of the real business world. Yet uncritical allegiance to these precepts over the last thirty years has produced a world in which corporations, especially in finance, are far less restricted in their pursuit of profit. We show in this book how this lawless environment has led the financial services industry to pursue its own unenlightened self-interest. The industry has become systematically predatory. Employees of industry firms have not confined their predation to outsiders; their efforts to loot their own firms nearly destroyed the industry and the entire global economy. Similarly destructive behavior by other players, often viewed through a distorted lens that saw all unconstrained commercial behavior as virtuous, added more fuel to the conflagration.

Some economists have opposed this prevailing ideology; indeed, comparatively new lines of inquiry focus explicitly on how economic actors can fool themselves or others into making poor, even destructive, choices. But when the economics profession has used the megaphone of its authority to dominate discussions with policymakers and the public, it has spoken with one voice, and the message has been the one described here.

Back to the current post. One issue that does not get the attention it warrants is despite the Fed and other central banks being vocal opponents of inflation, they are even more eager to avoid deflation, which hurts everyone but cash holders and the owners of extremely safe investments. The cost of servicing debt rises in real terms. That along with the with the typically depressed economic conditions that generate deflation, leads to business and consumer defaults and then potentially a self-reinforcing contraction in activity.

By Richard Murphy, part-time Professor of Accounting Practice at Sheffield University Management School, director of the Corporate Accountability Network, member of Finance for the Future LLP, and director of Tax Research LLP. Originally published at Tax Research

Chris Giles, the FT’s main economic commentator has said this morning has said this morning:

There is a fair chance that by the time the trees come into leaf in Washington, Frankfurt and London, this decade’s inflation crisis will definitively be over.

He added:

In the six months between May and November last year, for example, the annualised rate of consumer price inflation was only 0.6 per cent in the UK and 2.7 per cent in the eurozone. Excluding volatile energy and food prices, annualised core rates of inflation were 2.4 per cent in both economic areas over the same period.

And then he said this:

It goes without saying that the rapid demise of inflation on both sides of the Atlantic in the second half of 2023 was as surprising as its prior increase. Last summer, the Fed, European Central Bank and Bank of England all expected inflation to remain above target until 2025 at the earliest.

At which lint, I groaned with dismay that someone in such a position can have been s9 unfamiliar with the evidence. As I wrote in August 2022:

Danny Blanchflower had a longish discussion yesterday in which we agreed that the inflation that is dominating economic discussion about our economy at present is a passing phase. That does not mean it is not important. Far from it, in fact. But what it does mean is that when discussing inflation we have to remember that this is a temporary phenomenon, and what is just as important is to discuss what happens after it.

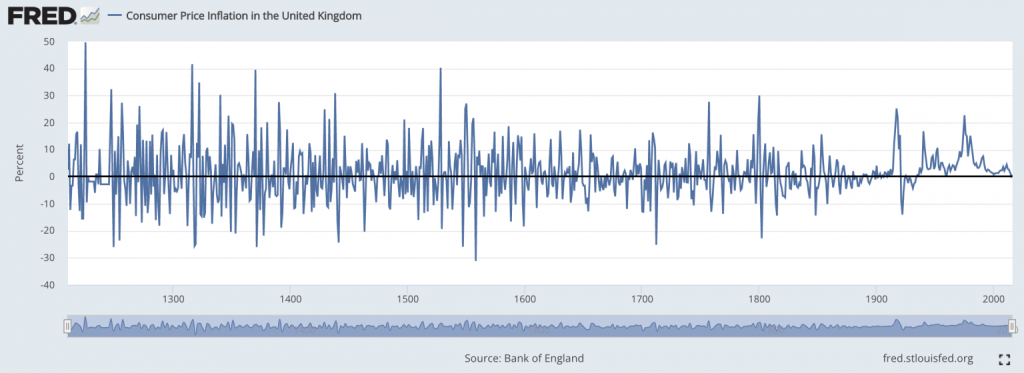

There is a lot of evidence to support this opinion. First, take this St Louis Fed chart which summarises data from the Bank of England on inflation trends in first England and then the Uk over a period of more than 800 years:

After a period of inflation there has, historically, always been been deflation, and even if the latter has been rare of late, there is always a return to more normal rates. Inflation does not persist.

The evidence is unambiguous. There never was going to be a struggle to bring inflation under control. Its return to mean, low, rates was always inevitable, and it is happening.

In that case the question is, what has been the cost of the mistaken belief of the likes of Chris Giles and the world’s cohort of central bankers who believed otherwise, contrary to all available evidence, and who have demanded and then unleashed economic mayhem on the world via totally unnecessary and utterly destructive interest rate rises in the meantime?

Rarely in the field of human endeavour has one rather small profession caused so much harm to humankind as neoclassical economists do now.

In the end the problem is that economists act as soothsayers for the rich and powerful.

Those that toe the line of their paymasters gets prestigious positions in academia and get to write influential columns in the press.

It is really sad that they have stuck with equilibrium thinking for so long, when the rest of of science, at least those that lean on predictive modelling, have embraced “chaos theory” (how, say, weather forecasts has become so good).

I am frankly amazed that this video where Samuelson admits his lot were peddling religion because they don’t trust us is still up on YouTube. (He also betrays the fact he doesn’t understand MMT but that’s another issue…)

Exactly, they are the courtiers of the rich and powerful. To go against mainstream economics is to kiss goodbye to tenure, private job positions etc. Just another bunch of willing careerists who accept the brain damage required to get a PhD in mainstream economics.

The function of economists in our society formerly performed by priests until gods became extinct is to explain to the unwashed masses why the people have to suffer.

3 myths that perpetuate the rapine:

1. gov debt is just like your household debt.

2.the water you swim in is of no consequence, little fish(and yer on yer own, btw)

3. the above rendering of the habit/conspiracy of treating a half sentence in Smith’s mighty tome as if it were the whole enchilada.

all 3 were topic in the feedstore parking lot during the 15-16 campaign.

Inflation is over? Not convinced. I am still seeing the cost of fuel, housing, and food go up.

I think the better question is who benefits? Inflation benefits the already wealthy who own assets that are increasing in value, while deflation benefits the savers as they are able to purchase more. We have had generations who have benefited from rising prices, but in the end, we have a cohort of people are on the wrong end of the asset inflation (those who do not own). These people would benefit from deflation….

By not allowing deflation, we now have a situation where when deflation occurs we will see massive numbers of people wiped out when they go underwater. (owe more in debt than the value of their asset) In the end, by not seeking equilibrium the end will be incredible hardship and pain as the whole system falls apart.

Richard Murphy is in the UK. Energy prices really shot up there and have come back. And the country is suffering from low growth.

Why is it that low growth makes us “suffer?” Who is “us?”

Um, inflation favours debtors and hurts lenders, and on balance the former are both poorer and more numerous than the latter.

Modern states avoid deflation because it’s a source of political instability. The only people who think deflation is a good idea are those who have never experienced it.

Taken in context of the opinion expressed by the author of this article (that man), the guiding principles of the Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 (spend more money to bring prices down) makes perfect sense.

After a period of inflation there has, historically, always been been deflation, and even if the latter has been rare of late, there is always a return to more normal rates. Inflation does not persist.

If that’s true why does everything cost more? And what scheme to measure inflation does the BofE use? Since so many of the great practices and ideas put into practice on in North America were first devised in Europe, I wouldn’t be surprised to learn that the good old BofE is not beyond massaging price data to prove that inflation is under control when that is how they want it look. But the larger point is that in economics, and sadly in so much of what now passes for science, data and statistics are used primarily not shed light but to be manipulated.

Um, did you miss that gas prices have dropped? And some food prices?

But yes, I should have been more pointed in the intro on my bit about central banks actually being in the business of fighting deflation more than inflation. If you look at US prices in the 1800s, you; regularly see a year or two of large increases (as in over 10% each year) followed by sharp declines.

It is important to be transparent about whether we are talking about indices using hedonic price correction or not. Once again, the tricky problem is that as society and technology change, there are changes in price related to how we use certain goods. It’s really a surprisingly difficult thing to calculate (I know you know this but just stating for the comments section). For the sake of argument you can use the example of whale oil price history to show how price is affected by a lot of factors. Or the price of slaves, to be more outrageous.

Is there a basket of goods whose use and availability has been steady enough to compare during the adoption of the hedonic substitute methods that began several decades back? That’s always the kernel of the argument saying CPI numbers are underreported.

Sadly these days, unbiased arguments are extremely rare, and some would argue they are impossible. Does anyone suggest a good source?

It had not occurred to me that hedonic price correction could apply to common vegetables except _in_extremis_. The exclusion of food and energy is also amusing, as if no one needs to go to work, travel, heat their dwelling, buy, make, or find clothing, and so on. But anyway, as a person who buys a lot of food for redistribution, and moves it around, I am acutely sensitive to the price of food and energy, and where I live (east coast of USA) it is not going down yet. However, I am encouraged to hear that it is going to do so any day now.

Would there be a ” hedonic premium” for high-nutridense common vegetables grown on highly mineralized, mineral-ratio-balanced bioactive counter-mainstream soil as against mainstream nutrient-free virtual vegetables grown on demineralized nutrient-depleted mainstream soil?

You can see that in the graph he uses as evidence. That graph is a very poor choice, it makes you wonder if it’s the best thing he had available, since it more or less contradicts his argument. There is a clear change in the data starting around 1900 – the inflationary periods last much longer, and after the depression, there has been no deflationary periods. With rates of change data, the cumulative effect is shown by the area under the graphs. Before 1900, there is almost no white space, and about as much of the graph is below the line as above, so prices stayed about the same over the long run. Not so much since 1900…..

Inflation is the rate of increase of prices, not the level. Zero inflation means prices stay the same. Prices going down is deflation.

So everything costs more because we had some inflation but no deflation. As the graph shows, deflation is no longer allowed.

While I agree with the general thrust of the article, I’ve always had a suspicion that ‘inflation’ was an excuse for the BoE to raise interest rates, not the reason. I believe the reason was to shore up sterling and to help capitalize domestic banks (rising interest rates were not passed on to savers to any significant degree). There is plenty of reason to think that the BoE is privately genuinely terrified that a significant fall in sterling with a consequent exodus of investment capital in UK property could cause a chain of bank failures.

Don’t forget the deaths caused by the Chicago Boys in Chile either.

Wondering if the threat of deflation to the token-power of money (because as prices come down, money is in less demand) is behind the push for destructive growth, mindless convenience, manufacturing-pollution, etc. And maybe even the primary reason why circular, energy efficient, recycling economies never get off the ground. Just too deflationary.

I could argue it being just the other way around – money being in higher demand – since only cash holders benefit from deflation as the real value of money is rising along with savings for future investments as expectations in deflationary environment project further price decreasing and rising real value of money – also reflected in the rising cost of debt servicing. Is there any theoretical foundation or empirical evidence that there is a connection between deflationary obstacles and recycling economics?

The entire field of matthematical economics is filled with indices manipultaed using questionable mathematical techniques. Most of the indices are poorly defind “averages.” For example, “inflation” is (defined(?) as an increase in the price of a represetative bag of commodities and services. ( “Inflation is a rise in prices, which can be translated as the decline of purchasing power over time. The rate at which purchasing power drops can be reflected in the average price increase of a basket of selected goods and services over some period of time. The rise in prices, which is often expressed as a percentage, means that a unit of currency effectively buys less than it did in prior periods. From Investopedia)

So what does this mean? What period of time, what is the basket made up of, where is this basket produced, etc.? Similarly, how is ‘growth’ defined? (Look it up!) And we go on and on.

Then the various “formulae” used to manipulate these averages all seem to be linear. Of course linear relationships are easier to manipulate and don’t go haywire when variables change. So much for sophisticated mathematics. Also, there are various kinds of “averages.”

And as for science, well what can one say. Science involves testing hypothesees for failures and anomalies whereas economics seems never to admit that predictions in economics are oftern simply wrong or irrelevant. How often do economists admit that they are wrong? And do ecomics departments ever admit that what they teach is more philospohy than reality?

The whole topic is a hopeless and continuous discussion by soothsayers over the disposition of dead chicken legs. I’m sorry. I am becoming incoherent while attemting to be honestly critical

Leaving aside the technical aspects of devising an economic “bundle” (which you mention and of which I’m well aware but don’t want to touch with a 10-foot bargepole), most people don’t realise how many strict mathematical properties must hold for various quantities to be “averaged” or manipulated. My bugbear when in academia was the rating scale (used in sooooooo many contexts that the average human encounters, like Rotten Tomatoes, Happiness scores, etc etc).

For my own personal scores on a (say) 0-10 scale to be manipulated, they must be cardinal. 4 must be twice as good as 2, yada yada yada. So if I give “Captain Marvel” a score of 1/10 and Catwoman 4/10 then the usual rules of mathematics (and odds ratios which any fan of betting will instantly know) must hold in terms of a choice between those 2 movies in a hypothetical choice in a hypothetical movie theatre regarding how often I’d choose Catwoman over Captain Marvel. Yet “real” choice data consistently disagrees with these ratings. Ergo, the ratings are…..the “s” word. In short, no human has ever been shown to use a rating scale according to the properties it must hold in order for “averages” and other mathematical manipulations to hold.

And don’t even get me started on the fact that in certain cultures, certain numbers have connotations (death, a…..hard member,…..a….soft member…..ahem). Rating scales mean nothing. (Plus why do some countries with very high happiness scores also have high suicide rates? Yeah yeah yeah maybe the low score people “unalived themselves” if we want to use the YouTube enforced vernacular).

But the bottom line is you really need to look at the whole picture, do what people like PlutoniumKun said elsewhere about looking at medians, not means, but also go a lot further in thinking just how many mathematical rules must hold for an average to be meaningful. But. more worryingly, how often we accept these because the quantity of info thrown at us has become so large that we can’t physically devote enough time to mentally say “STOP! I need to think”. It’s kinda why forums like this help us contextualise things.

The above plot only shows the percent change per year, some years inflation, some deflation. You need to integrate to actually see the trend. I know a candy bar cost a nickel in the fifties, an ice cream cone a dime. Most prices always rise over time. Although I will say the price of computers has come down since the 1950s.