By Hanhui Guan, Associate Professor at Peking University, Nuno Palma, Professor of Economics in the Department of Economics, and Director of The Arthur Lewis Lab for Comparative Development at University Of Manchester, and Meng Wu, Postdoc Fellow in Economics at University Of Manchester. Originally published at VoxEU.

In early-13th century China, the Mongols introduced the silver standard, the first paper money in history to be backed by a precious metal. This column studies the rise and fall of paper money in 13-14th century China over three stages: full silver convertibility, nominal silver convertibility, and fiat standard. Military pressure in particular led to the over-issuance of money, especially under the fiat standard. Eventually, over-issuance led to high inflation as the dynasty collapsed. China’s historical experience underscores that economic prosperity hinges on the effective execution of sound policies, a process influenced by the political landscape.

China’s economic performance over recent years has raised global concerns. Compared to its past four decades of miraculous growth, the country is now facing an economic slowdown. A property market crisis, stock market slump, consumer price fall, and currency depreciation have triggered anxiety about whether the world’s second-largest economy is entering a recession. The uncertainty about the country’s future also prompts Chinese policymakers to recalibrate some of its policies and seek new sources for growth (De Soyres and Moore 2024). In a recent talk, President Xi emphasised high-quality financial development. According to Xi, an array of elements will accelerate the construction of a modern financial system with Chinese characteristics: a strong currency, a strong central bank, strong financial institutions, strong international financial centres, strong financial regulation, and a strong financial talent pool (Xinhua 2024).

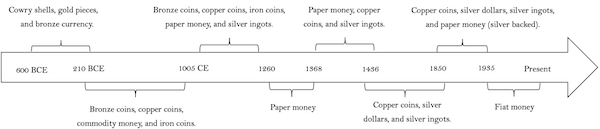

Looking back to Chinese history, we can find that when managing the state, Chinese rulers and their ministers have often been innovative in developing monetary policies and designing financial instruments. As early as the sixth century BCE, the famous philosopher and politician Guan Zhong noted that regulating the quantity of light money (debased coins) in relation to heavy money (fine coins) was a “mutual relationship between child and mother”. Later, in the 11th century, the first paper money, called jiaozi, appeared in parts of China. In the early 13th century, following the conquering of North China, the Mongols introduced the silver standard, the first precious metal standard backing paper money in history. When Kublai established Mongol dominance over Mongolia, China, and Korea, founding the Yuan Empire in 1271, he announced that silver-backed paper money was the sole legal tender. From then on, a paper money economy, backed by silver, replaced a previously chaotic monetary system that mixed various types of paper money with copper coins, iron coins, and silver ingots (Figure 1).

Figure 1 The evolution of currency formats from 600 BCE to the present

Source: Based on von Glahn (2016: 1–294).

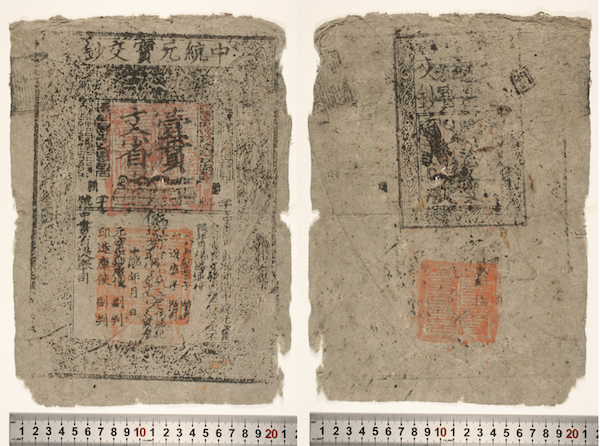

In a recent paper (Guan et al. 2024), we study the rise and fall of paper money in Yuan China (Figure 2 shows an example). Based on a wealth of printed primary sources, we constructed a new and comprehensive dataset of the Yuan Dynasty’s annual money issues, price indices, imperial grants, population, taxation, warfare, and natural disasters. The data series, substantiated with qualitative historical evidence, enables us to study the evolution of the Yuan Empire’s monetary regimes, examine the relationship between paper money issues and the government’s fiscal constraints, and investigate the factors that explain the over-issuance that eventually led to high inflation as the dynasty collapsed.

Figure 2 A 1 guan note zhongtong yuanbao jiaochao 中统交钞 issued by the Yuan

Note: Size: 34x20cm. Preserved in the China Numismatic Museum in Beijing. Reproduced with permission.

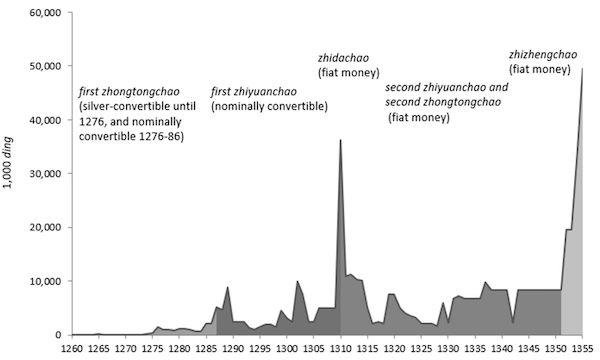

Figure 3 plots the annual nominal money issues. It shows the Yuan government issued four paper monies in total, namely, the zhongtongchao (1260–86), first zhiyuanchao (1287–1309), zhidachao (1310), second zhiyuanchao (1311–51), and zhizhengchao (1352–68). Despite its initially modest quantities, the issuance of the zhongtongchao increased steadily over time. The issuance of the second paper money, zhiyuanchao, was intended to tackle the depreciation of the zhongtongchao. During its 23 years in circulation, the annual issuance of the zhiyuanchao remained relatively stable.

The third paper money, the zhidachao, circulated for only one year, but, compared with the first and second paper money, the size of the issuance was striking. The issuance was a fiscally motivated response to a regime change: it followed the enthronement of the third Khan, Külüg (r. 1307–1311), who seized power through a military coup. However, he died suddenly only one year later, and the zhidachao was abandoned.

From 1311 to 1350, both the zhongtonchao and the zhiyuanchao were reintroduced, and the issuance of paper money varied from 2 million to 11 million ding. The last paper money type, the zhizhengchao, was issued in 1352. Compared with the previous issues, the annual issuances were even more striking. Within two years, the annual issuance soared from 20 million to 50 million ding. Contemporary scholar Wang Yun wrote that unrestrained printing of paper money made it into nothing but empty script (von Glahn 1996: 61–3).

Figure 3 Annual nominal money issues, 1260–1355

Notes: The ding 錠 was the unit of account of silver, with 1 ding of silver being equal to 50 liang of silver. The Yuan government used ding as the unit of account to record fiscal revenues and expenditures, and regulated that 1 ding was equal to 50 guan zhongtongchao. Our last year is 1355 because no data exists after that year.

Sources: See Guan et al. (2024).

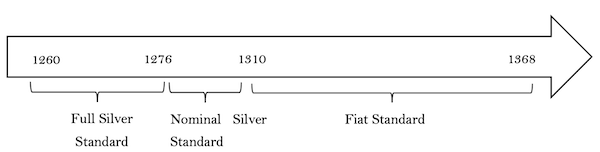

Based on historical narratives, we divide the Yuan’s monetary regimes into three stages: full silver convertibility period (1260−75), nominal silver convertibility period (1276−309), and fiat standard (1310−68). During the first of these, the issuance of paper money was backed by a quantity of silver at a fixed exchange rate. Throughout the nominal silver standard, the new issuance was no longer fully backed by reserves and was only convertible when the local exchange bureau had silver. When the Yuan government began to print the third paper money, zhidachao, in 1310, silver did not play the reserve role, and thus, the monetary system changed to de jure fiat money after 1310 (Figure 4).

Figure 4 Monetary standards during the Yuan Dynasty

Source: Our figure, based on the information in Peng (2020: 501–28).

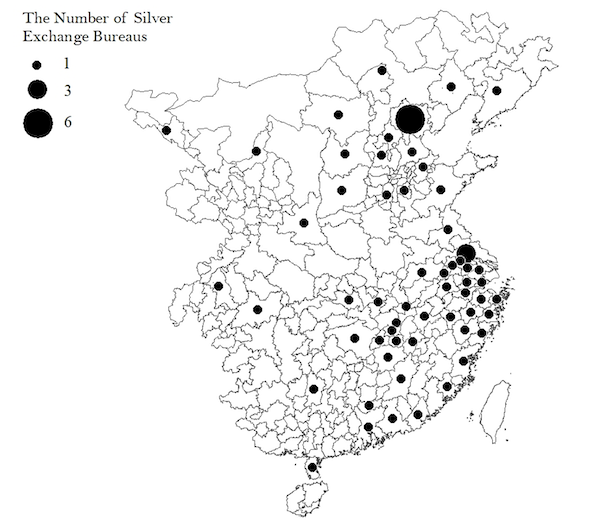

Figure 5 plots the locations of silver exchange bureaus in the 1290s. It shows that the government set up exchange bureaus at provincial-level cities, lu 路, or prefecture-level cities, fu 府 and zhou 州. People could exchange paper money for silver at a discount of 70% to 80% of face value, bring damaged notes, and obtain new notes in exchange by paying a small commission fee of 3%. For people who lived in west or central China, there were fewer places for them to redeem silver. Given the size of China, it would have been costly for people who lived in the remote parts of the west or those who lived in smaller towns to travel to cities to exchange silver.

Figure 5 Location of silver exchange bureaus, around the 1290s

Notes and source: See Guan et al. (2024).

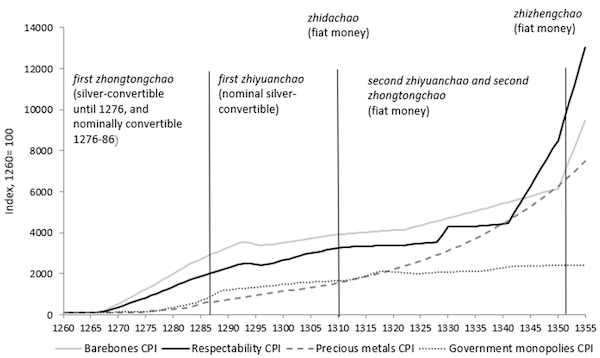

To assess the value of real money issues over time, we construct four price indices: a barebones consumer price index (CPI), a respectability CPI, a government monopolies CPI, and a precious metals CPI. As Figure 6 illustrates, the empire began to experience inflation in the 1270s, when the issuance of zhongtongchao began to grow. The price level also indicates that the 1290s to the 1330s enjoyed price stability. Besides this, we find that during the last decade for which data is available, 1346–1355, the compound inflation rate was 12.7%, corresponding to an approximate doubling of the price level from 1346 to 1355. All four price indices increased over these 96 years but at different magnitudes, as seen in the figure.

Figure 6 Four price indices, 1260–1355

Notes: For methodological details, see Guan et al. (2024).

Source: Our calculations are based on the underlying data collected by Li (2014).

Contemporary observers and scholars documented that warfare, imperial grants, and natural disasters were major causes of the fiscal actions observed. Using econometric analysis, we explored how these factors correlated with the quantities of paper money issued and studied the role of the silver standard in regulating paper money issues. We find that military pressure, particularly civil war, generated fiscal demands that led to the over-issuance of money. By contrast, natural disasters and imperial grants did not trigger the over-issue of money. Warfare was much more likely to increase paper money issues under the fiat standard than during the silver standard period.

Our findings echo studies of the classical gold standard (Bordo and Kydland 1996, Eichengreen 1987, Obstfeld and Taylor 2003). We show that similarly to the classical gold standard, the full silver standard (1260–1275) in Yuan China proved a commitment mechanism that constrained the over-issuance of paper money – while it lasted. The nominal silver standard proved successful given that the price level remained stable into the first half of the fiat standard period. However, by the time the Ming toppled the Yuan Dynasty in 1368, paper money was close to worthless, and towns and cities were resorting to a barter economy (von Glahn 1996: 70). Following the definite collapse of paper money under the fiscally weak Ming regime, China would have to wait several centuries to return to paper money, influenced by Western technology and institutions (Palma and Zhao 2021).

China’s historical experience underscores the notion that sustained success cannot be assumed, both throughout history and in contemporary times. Economic prosperity invariably hinges on the effective execution of sound policies, a process profoundly influenced by the dynamic political landscape.

Fascinating article. One might be tempted to extrapolate this to the US dollar, but of course it’s different this time.

A major difference being the outsourcing of money printing to the private banks via debt creation.

When I was pushing old metal and banknotes, China was very much the sick man of numismatics & notaphily-frankly few cared about it-thus I never delved into their monetary history as I did in countries where coins & banknotes were valued and sought after.

…which makes for interesting reading, this article!

China was very much a silver-based economy, not gold. There were only a handful of gold coins ever issued in say the past 300 years until 1949, and none in the vast past previously.

To compare it to our Silver Certificate banknote era (1878 to 1968) might be instructive…

I never quite understood the need for Silver Certificate banknotes as all of the coins from a Dime to a Dollar were 90% silver until 1964, and it wasn’t as if you wouldn’t receive silver coins for exchanging a Federal Reserve Note, United States Note or Legal Tender Note, as there was no alternative.

The Federal Government decreed that for a 1 year period starting from June 24th 1967 to June 24th 1968, you could exchange Silver Certificate notes for actual physical silver and the rush was on!

A brisk trade was being done by coins dealers buying them up from the public and each $ worth of Silver Certificate was worth around $2.50 in physical silver, and the only place the exchange could be done was the U.S. Assay Office in San Francisco.

After June 24th 1968, they were no longer redeemable and became worth only a smidgen over face value-nobody cared.

p.s.

Just noticed that our Silver Certificate notes went away exactly 600 years after China’s, what are the odds?

The book Empire of Silver: A New Monetary History of China by Xu Jin may interest you.

Nice article, and thanks!

A few items of note:

a. War caused the government to rapidly increase the issuance of fiat

b. The CPI indexes were showing inflation at all times; only the rate of inflation changed

c. The CPI indexes accelerated rapidly as the issuance of currency accelerated

I wonder:

a. Why the always-increasing CPI? There appear to be no instances of deflation.

b. Always-increasing CPI, during times of relatively small money-supply increase … makes you wonder: why are prices increasing? Is it because:

1. cost of inputs (relative scarcity) is rising?

2. more people are chasing relatively static inputs (population increase while underlying productivity of natural and tech world stays static)

One other thing I wonder about. My understanding of China is that it never really did the empire thing. The battles were interior battles over power, not exterior battles to acquire resources.

In the Empire setting, war is a relative constant, so you’d expect to see inflation. There was inflation around the time of the first world war, and a little after WWII. See this link, and scroll down a little for the chart.

But U.S. inflation didn’t really get going until the late 1960s, and by 1971, President Nixon announced that the dollar was no longer convertible into gold.

So there are some parallels between this instructive history of Chinese money, and our modern situation here in the U.S.

If you look at the inflation chart above, you see that inflation really got hot in the U.S. during the 1980s.

What was the driver of all that inflation? No big wars were happening. Costs of inputs rose (oil crisis), and that certainly had an effect. But deficit spending at the Federal level didn’t really take off till the early 2000s.

Can anyone comment on what caused the inflation to rise so much during the 1980s here in the U.S.?

80’s? That doesn’t match what I remember. Inflation was bad during the 70’s, and was the reason for the Volker interest rate shock treatment. I suspect you’re the victim of poor graph design, with the slanted decade labels at the bottom axis located under the previous decade, where they are intended to mark the beginning of each decade. If you hover over the individual data bars, you’ll see that the peak year was ’81, with a sharp dropoff in ’82 thanks to the interest rate spike.

Thanks for the tip.

I revisited the graph, and … realized I didn’t pay close enough attention.

https://fred.stlouisfed.org/graph/?g=1iSvs

January 15, 2018

Consumer Price Index and Consumer Price Index Less Food & Energy, 1968-1987

(Percent change)

Milton Friedman: It is always and everywhere, a monetary phenomenon. It’s always and everywhere, a result of too much money, of a more rapid increase in the quantity of money than an output.

Anything else is a smokescreen to confuse the uninitiated.

QE is money printing as Fed will never reduce her balance sheet.

I define inflation as CPI + asset prices and velocity of money more or less stable over time.

I read somewhere that Kissinger had asked the Saudis to jack up the oil price…

Wasn’t the oil price the main driver of the inflation?

Volcker IIRC was Rockefeller man just like Kissinger and of course he used the crisis to basically break the back of Unions and the Blue Collar class.

Maybe someone else can comment

Take it from Keynes: There is no subtler, no surer means of overturning the existing basis of society than to debauch the currency. The process engages all the hidden forces of economic law on the side of destruction, and does it in a manner which not one man in a million is able to diagnose.

That is precisely the smoke screen, 1000 economists will come up with 1000 different reasons for it , but it’s mathematically impossible for all prices to increase in aggregate provided a +/- stable velocity if money supply is not increased or output hasn’t changed. It’s as simple as that.

Oldtimer: thanks for these posts. I’d like to emphasize that inflation isn’t _necessarily_ a monetary function, and you pointed that out yourself when you said “or output hasn’t changed” above.

There are many causes of output change that don’t involve the money supply, like a supply shock (oil embargo) or foreign tariffs applied to a country’s exports, for ex.

So inflation can still happen if the money supply stays static, or even falls, _if output is falling faster_.

Output isn’t monetary policy. It’s (possibly) economic policy, but it isn’t centered on money supply mechanics.

And what if people (vendors) just raise their prices? Money supply might well be constant, and supply is constant, but people raise prices anyway. We saw that during the Covid “here’s your chance to raise prices, you can use Covid as the excuse” episode just a few years back.

And at the same time, people got free money, and even though prices were going up, they bought even more, and bid up the prices for everything. Expectations had a role in the inflation. And yes, some (by no means all) of that was the vastly increased money supply via helicopter money.

Lastly, you said something very interesting, and I hope you’ll elaborate on this quote from your post above:

What are “the hidden forces of economic law” you’re speaking of?

Clearly some prices will go up or down based on supply but if my understanding is correct Friedman is talking about aggregate prices, so if some people will get away with high prices for some time but eventually if money supply is not increasing, people simply have no money left to buy other stuff so a balance will be restored. It’s only because supply of money is increasing that price levels set up permanently higher.

You are falling for the quantity theory of money. MV=PQ itself is true (by definition) but the assumption that V is constant is false. The assumption that Q is constantly at capacity is also false. The assumption that these four variable are all independent is dubious. One could imagine an increase in M might encourage an increase in V and thereby Q all without increasing P, until Q is maxed out.

In general, a good rule of thumb is that if Friedman said it, it’s wrong.

Friedman was aware of it and he expressly says provided velocity is constant in his writing. Granted velocity is not constant but as someone posted the chart, it’s variation isn’t wild. It has stayed between 1.5 and 2 over the last 100 years.

It also assumes that all money is spent which is false. It assumes banks operate by fractional reserve lending which is false. It assumes money is simply a medium of exchange which is false. It assumes the money supply is controllable which is false.

Whilst Milton Friedman peddled this nonsense long after it had been comprehensively debunked, it was actually invented by Irving Fisher.

https://fred.stlouisfed.org/graph/?g=BkzA

February 25, 2015

Velocity of M2 money stock, * 1960-2014

* https://krugman.blogs.nytimes.com/2015/02/25/monetarism-in-winter/

The velocity of M2 — the ratio of nominal Gross Domestic Product to a broadly defined version of the money supply — has turned out to be hugely variable.

Paul Krugman

I guess Friedman never had to try to buy bread during a famine. For some reason those prices tends to go up unconnected to the money supply.

I think Friedman’s statement is a smokescreen to confuse the uninitiated.

Basically war is an insatiable hole of demand.

The almighty buck has lost 99% of its value since 1971 when measured against the value of all that glitters, but everybody agrees that last 1% is gonna be a hard get.

The unquestioned reliance on a quantity theory of money makes it hard to frame and ask important questions about the state of banking institutions or the fiscal taxation capability of the state.

Paper money has historically proved to be a curse in the end to all nations that adopted them.

You can just as easily say metallic money has historically proven to be a curse. Certainly in the US experience, hard money was a big factor in impoverishing the little people and kickstarting our oligarch overlords.

It is largely correct as government and emperors have always tinkered with coins as well.

The difference is one of degree, as metallic money will not prevent recessions, deflations and some time inflations, its only paper money that can generate hyperinflations which are “end of society” events.

Here are 760 years with the Pound, and still the Pound and United Kingdom continue:

https://fred.stlouisfed.org/graph/?g=1iSBO

January 4, 2018

Consumer Price Inflation in United Kingdom, 1250-2010

(Percent)

Monetary policy is always difficult. Having your money supply controlled by the amount of precious metal, or oil, or wheat disconnects it from the monetary needs of the society. And hard money isn’t safe from inflation. Spain developed horrible inflation when silver from the New World flooded in. And if the society grows, but the money supply does not, debtors get crushed in the deflation.

Ideally the money supply grows with growth in the economy, but it is always tempting to crank up the presses. It does seem the the temptation eventually becomes too much in all cases. In the US is is requiring more $$$ in debt to fund $ in growth, a bad sign.

European countries issued very little in the way of paper money in the 19th century…

The action really gets going after WW1, when most every country was stony broke from the war.

Good article, thx.

I’d note that Fractional Reserve Banking is one of those rare things *not* invented by China, so it makes sense that the Monetary Theory of inflation would apply more strongly (signal not amplified/distorted by feedback in the banking system).

Questions:

– What is “Respectability CPI”?

– and why does it take off 10 years before the fiat money shock of 1350? (when the zhizhengchao cranked up the Barebones CPI). I’d guess that “respectability CPI” relates to interest rates, which would rise when lenders start to lose faith in the stability of the political system?

As to why it takes off 10 years before 1350, I would guess it has something to do with the decline of mongol power in the 1340ies. As state power declines, its currency loses value (because the value is backed up by state violence).

I think it is likely that the printing in 1350-1355 is more in response to decline of state power, then the cause of it. Printing new money, offering a limited window to trade in old money, and then declaring old money to be worthless is a way for states to redistribute power. And if the government is already losing control, redistributing power away from people and territories you are already losing is a reasonable move.

I notice that the article does not mention withdrawal of currency. Considering the spike in issuance in 1310 and the lack of inflation, I would figure the chinese emperors did withdraw money.

I interpreted respectability CPI to be the deflator for the basket of goods required for a respectable, i.e. middle-class life. A scribe or minor official or local merchant. Probably requires a horse and house and some decent threads, rather than the CPI for subsistence living with gruel and hovel and rags. Intra-elite competition as the state declined into looting or press ganging resources may have resulted in these positional goods showing higher inflation than peasant commodities.

I think the article jumps to its conclusion that rampant money printing led to military collapse. The history of hyperinflations (Weimar Germany, post WW Hungary etc) is that they arise when the populace loses faith in the currency / state (I.e. the opposite causation than that claimed). They are rarely associated with a lack of real resources.

My guess is the Yuan subjects could see the regime was doomed and ceased to accept the currency, preferring silver which they knew would be accepted by the new bosses…. The currency implodes as a symptom of the state imploding.

It would interesting to know what data exist as a measure of state capacity and plot thus against the CPI – I suspect square miles under effective control / taxation plummets in lockstep with the currency, as lands succumb to warlordism or banditry or are seized by the enemy. It would be instructive to plot availability of real resources collapses as the alternative argument.

And on this topic, let’s watch what happens in Ukraine. I wonder if there is a graph of their CPI?!

This schematic overview of the experience of paper currency in China from 1260 -1368 does not mention any monetary or fiscal policies or tools used by the Chinese administrators to stabilize their political economy: how were new issues released into the market and how were dated issues collected and destroyed; what were the uses, limitations and impact of paper currency for trade (foreign) and commerce (internal); how did the paper currency relate to taxation; how did it assure the existing social relations and the redistribution of resources, etc.

The fiat ‘Assignat’ currency issued by Revolutionary France from 1792 – 1796 was significantly modified when it was required to bankroll the institutions of the War Economy inaugurated on August 23, 1793. Despite legislation to the contrary, barter and truck exchanges in the domestic economy continued to take place and were permitted alongside the Assignat. More importantly, even after the collapse of the Assignat, the emerging bourgeoisie of France recognized that fiat currencies were inevitable for financing the imperial ventures that would enable them to assert new and traditional commercial trade routes and to centrally support the necessary transition to a market economy, hence the push to persuade Napoleon to create the the Bank of France in 1800 and the “Mandat Territorial” and to continue to depend on the Bank of France to issue and guarantee the currency and credit required to re-animate the expansion of trade.