Yves here. This is an elegant and persuasive analysis that shows how foreign aid donations reflect donor state self-interest. It would be nice, but also a lot to ask, to see how US aid correlates with our military presence in various recipient states. Israel alone tends to prove out that assumption but it would be useful to see how well that relationship holds elsewhere.

By Rabah Arezki, Senior Fellow Foundation for studies and Research on International Development (FERDI); Director of Research French National Centre for Scientific Research (CNRS); Senior Fellow Harvard Kennedy School; Youssouf Camara; Frederick Van Der Ploeg, Professor of Economics University of Oxford; and Grégoire Rota-Graziosi. Originally published at VoxEU

Critics of foreign aid are often quick to point out the faults of recipient countries. This column looks at the motives of the donor countries themselves. Examining the flow of foreign aid following major discoveries of natural resources, the authors find that aid flows tend to increase following a discovery despite the recipient country becoming wealthier. The finding suggests that donor countries are not entirely altruistic, but prioritise access to valuable natural resources and their strategic interests above recipient need.

Critics of foreign aid often focus on deficiencies in recipient countries. In this column, we explore whether foreign aid from donor countries is self-interested. We provide empirical evidence that recipient countries that experience major natural resource discoveries receive more, not less, bilateral aid (all else equal). This is a paradox, considering that major discoveries are associated with an effective relaxation of international borrowing constraints. Given the role of critical minerals in the energy transition, foreign aid is likely to continue be used to further the interest of major powers at the expense of poorer countries.

Critics of foreign aid often focus on deficiencies in recipient countries and related aid ineffectiveness (Bauer 1972, Easterly 2003, Edwards 2014, Frot et al. 2012, Fuchs et al. 2012, Galiani et al. 2016, Lohmann et al. 2015). The criticism is especially salient in the case of bilateral aid as donors stand to benefit from a potential quid pro quo with recipients. This quid pro quo may centre around access to markets, but perhaps more importantly, also around access to natural resources in developing countries. Indeed, developing countries are less industrialised and tend to consume fewer natural resources than they produce. That situation lends itself to influence over these resources by foreign economic powers given (known) reserves. Yet, there has been little systematic analytical or empirical exploration of whether foreign aid donors pursue their own self-interests when giving aid (Fuchs et al. 2012).

Throughout the 19th century, Western European powers competed to secure access to natural resources such as cotton, copper, iron, and rubber, which were critical for their industries. These colonial enterprises were undertaken through coercion and military might. In the modern era, a new race between major economic powers to secure critical resources for their industries is at play. The race between these economic powers is especially acute nowadays given the two main technological transformations taking place today, namely, decarbonisation and digitalisation. To dominate the new industries emanating from these transformations, it has become vital for major powers to secure access to critical minerals such as lithium, cobalt and rare earth.

The Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) is rich in mineral resources. It has the world’s largest reserves of cobalt, a critical component for batteries in electric vehicles, and is responsible for 68% of the world’s production. It is no surprise that DRC has become the darling of major economic powers such as China, the US, and the EU. The latter are simultaneously committing to foreign aid and signing major mineral contracts. Other anecdotal evidence of the concomitance between foreign aid and natural resource abundance plays out in Guyana, Mozambique, Mongolia, Namibia, and Papua New Guinea. Rather than using coercion, as was the case in the 19th century, bilateral foreign aid can be viewed as ‘greasing the wheels’ for the signing of lucrative mining contracts – for exploration, extraction, and ultimately trade flows. In other words, traditional donors as well as non-traditional donors such as China are in a contest to secure natural resources located in developing countries by granting aid.

Identifying Self-Interest of Donors

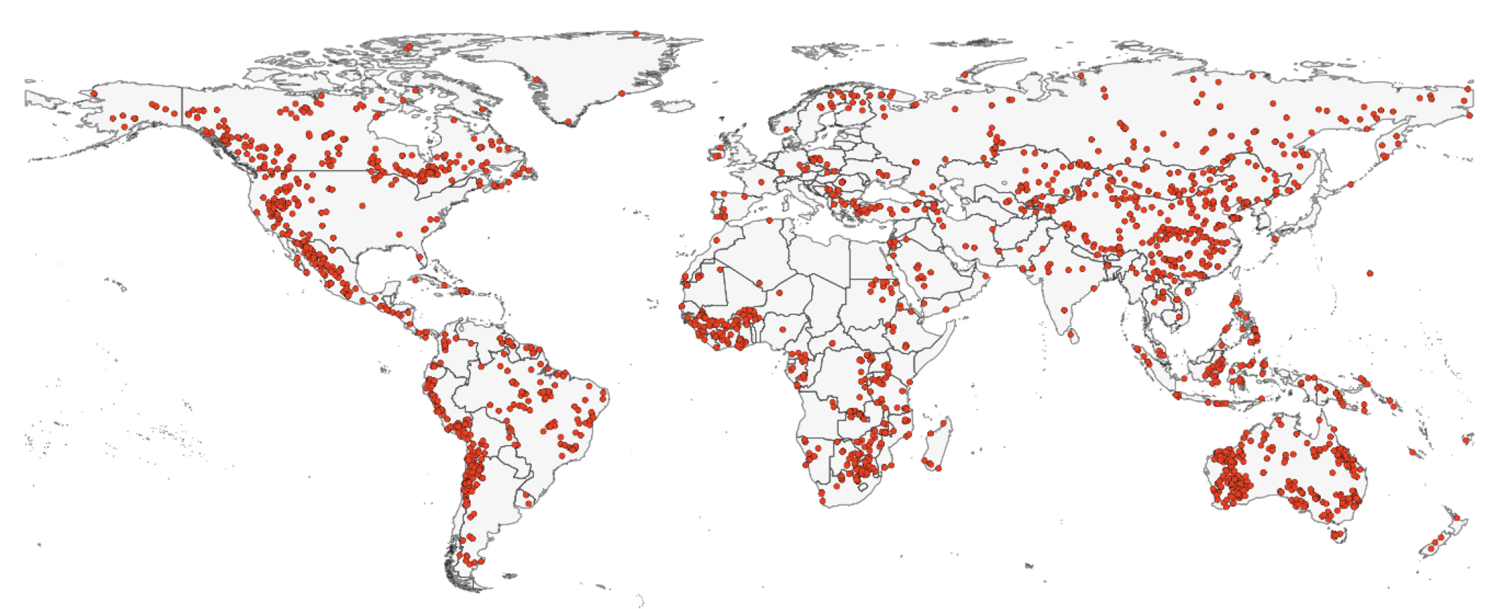

In a recent paper (Arezki et al. 2024), we explore more systematically whether foreign aid is self-interested. To identify elements of a self-interest motive in donors’ decision to allocate foreign aid, we exploit the timing and size of major discoveries which can be argued to be plausibly exogenous (see Figure 1). Major mineral discoveries are salient shocks: the median discovery is 29.81% of GDP. Such discoveries are also frequent and widespread: over the past decades, there have been hundreds of discoveries of mineral (and hydrocarbon) resources all around the world including South Asia, Latin America and most notably sub-Saharan African countries.

Figure 1 Mineral discoveries have become a salient feature in the developing countries

Source: MINEX

A consequence of a major discovery is an immediate increase in (known) wealth. In this way, the discovery raises the value of the collateral countries could use to borrow internationally, alleviating potential external borrowing constraints – even before the resource is effectively extracted. Considering the above, countries experiencing major discoveries should receive less rather than more foreign aid.

Consider a mental experiment where donors are given the choice to provide aid to two otherwise identical countries that differ only along one dimension, namely, the occurrence of a discovery. The choice of aid allocation should be directed towards the country without a discovery if donors are exclusively ‘altruistic’ (i.e. poverty reduction in recipient countries is their primary objective). If donors are also sufficiently motivated by ‘self-interest’, however, aid may go towards the country which discovered resources. Indeed, self-interested donors attempt to secure access to the newly discovered resources. In a simple two-by-two donor-recipient model with a contest success function, we formalise the intuitions from this mental experiment to analyse the effect resource discovery on foreign aid.

A New Paradox of Foreign Aid and Natural Resources

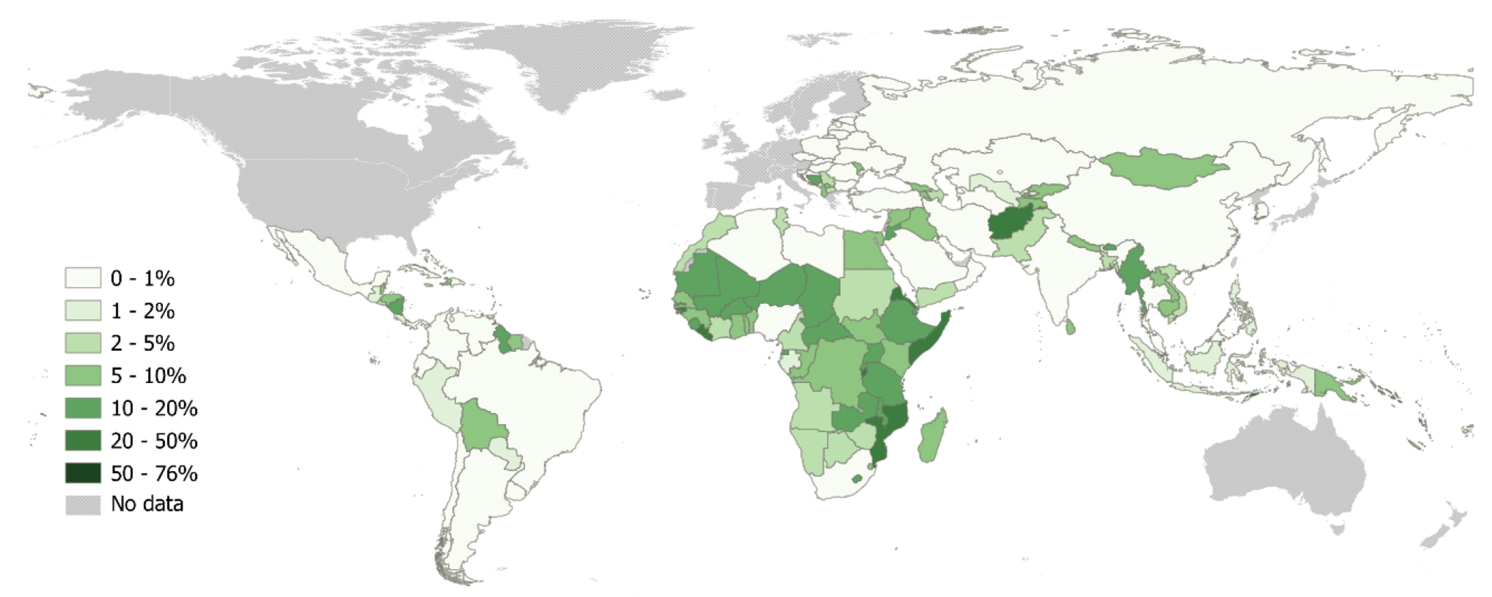

The paradox we explore is that as developing countries become (relatively) ‘richer’ on account of major discoveries, they tend to receive more rather than less foreign aid. Foreign aid – as defined by the official development assistance as recorded by the Development Assistance Committee – is a drop in the bucket for traditional donor countries, at about $214.4 billion, or 0.37% of their combined gross national income (GNI), in 2023. But foreign aid is a major source of funding for most developing economies. Moreover, exporters of mineral resources such as DRC, Mongolia, and Zambia have remained as recipients aid, with historical peaks reaching 67%, 17% and 57%, respectively, of their GNI (see Figure 2).

Figure 2 Foreign aid remains significant portion of income in developing countries

Source: OECD (2024)

Our empirical estimates are consistent with the predictions of the theoretical model when adding a donor self-interest motive. Our core estimate suggests that following a mineral discovery, recipient countries obtain on average 36% more aid than countries without such a discovery. Results show that recipient countries that discover major resources receive more aid, more quickly, everything else equal. We verify that the grant and not just the loan components of aid increase following a discovery and that the flow of bilateral aid increases more from the country of the nationality of the discoverer. Results are robust to a wide array of checks including accounting for the nature of discovery, the heterogeneity of donors and recipients, and using different estimators.

Consistent with the predictions of the theoretical model, estimates show that after a major mineral discovery, the current account and saving rate decline for the first five years and then rise sharply during the ensuing year. These results suggest that countries experiencing giant discoveries borrow from the rest of the world well before extraction starts. We document that major mineral discoveries lead to a deterioration of the current account implying the country borrows from the rest of the world. Mineral discoveries imply that a country is richer than previously thought and hence tending to relax external borrowing constraints. The increase in foreign aid following major mineral discoveries thus suggest that donors are self-interested.

Conclusion

These results have important policy implications. Although several traditional donors in advanced economies have announced they would limit the amount of foreign aid, it is likely that foreign aid could continue to play a key role in helping securing access to critical minerals. The extraordinary growth in demand for critical minerals is putting upward pressure on prices and stimulating new critical mineral discoveries all around the world. In developing countries, this new bonanza presents opportunities but also important risks (Arezki and van der Ploeg 2024). Absent governance system shifts, the rush for critical minerals risks could create a ‘new curse of critical minerals’. Given the role of these critical minerals in the energy transition, foreign aid is likely to continue be used to further the interest of major power at the expense of poorer countries.

Erratum:

Here’s the missing map of the global distribution of ‘foreign aid’ :

https://cepr.org/sites/default/files/styles/flexible_wysiwyg/public/2024-11/arezki13novfig2.png?itok=2DD3FXu4

Thank you.

Ok, so the author is obviously not a chemist.

Nice to see some data validating a Captain Obvious analysis.

It would have been interesting to see how the aid is used and provided between China and the West. How much of the aid was used for military? For Debt service? For hospitals, schools, and light rail? no mention, not even in the discussion.

But then again, EU de-risking China likely indicates a third and dangerous rail best not to think about or discuss. Is the Overton window shrinking WRT China?

It’s hard to know how to evaluate an argument that doesn’t define “aid” and doesn’t really provide any detailed figures for anything.

The first thing to understand is that “aid” hasn’t involved giving money to governments for a long time now. If you take “aid” to be the development budgets of major donor nations, the EU and UNDP etc. then a significant part of those budgets goes in running costs and project costs. Much of the remainder is recycled domestically in things like consultancy fees, secondment of national experts, conferences and visits to the donor country etc. Rory Stewart, who was Development Minister is the last Tory government recounts the story of a project with a budget of £50,000 where all but £2000 was consumed by the Departments own costs, consultants, travel costs, project management etc. This is admittedly an extreme case, but in my experience not a unique one. The tendency these days is to work with local and regional authorities rater than central government, and to work through local NGOs and “civil society” organisations funded by western donors. Such initiatives (especially the latter) don’t buy any favours from government, who consider, with some justice, that they are just a disguised form of neocolonialism, setting up centres that have a considerable amount of influence but are not subject to any democratic scrutiny.

In addition, aid donors prefer safe projects which play well at home. In a country like the DRC, which is the one I know best from this list, you can get money for human rights and gender-sensitivity training for the Army, for example, but not to pay the soldiers properly or train them correctly. You can get money for civil-society engagement but not to improve the police, because the latter is too controversial politically. But until the government in Kinshasa can actually get a grip on the country, and chase out the Rwandan-backed militias in the Kivus, it can’t get control of the resources and it can’t develop the country.

For decades now, scholars have talked about the “resource curse” in Africa. The discovery of raw material deposits creates instability, not stability, because it encourages a political and economic system based on rent extraction, and conflict between different groups to control revenue streams. The authors really should know this.