Yves here. US popular mythology puts taxation without representation as the driving force behind the American rebellion against England. This article contends that high and uneven taxes, particularly imposed without consent, were central to the French Revolution. Trump’s tariffs are the poster child for arbitrary taxes imposed without citizen or legislative approval. And the US’ level of inequality is higher than that of pre-Revolutionary France.

By Tommaso Giommoni, Gabriel Loumeau, and Marco Tabellini. Originally published at VoxEU

Extractive taxation is considered one of the main causes of the French Revolution. This column exploits regional variations in the French salt tax, which accounted for 22% of royal revenues in 1780, to document that areas of France burdened by a higher tax rate experienced more revolts in the years leading up to the Revolution. These effects were amplified by droughts that increased food prices and activated latent discontent. It suggests that when taxation is imposed without representation, it can become a catalyst for popular unrest, especially after negative economic shocks.

The French Revolution dismantled the Ancien Regime and ushered in a new political order, redefining state power and institutional structures. Its transformations – from the abolition of feudal privileges to the creation of modern bureaucratic and legal frameworks – extended far beyond France, shaping institutions across the world. Although the causes of the French Revolution are complex and multifaceted, one widely recognised factor is extractive taxation (Norberg 1994). However, despite its prominence, to the best of our knowledge, no systematic evidence exists on the hypothesis that extractive fiscal institutions were an important determinant of the French Revolution.

Our recent paper (Giommoni et al. 2025) seeks to fill this gap, exploiting geographic variation in the incidence of the salt tax – considered one of the most “iniquitous institutions of the Ancien Regime” (Sands and Highby 1949). First introduced as a temporary measure in the mid-13th century and then made permanent one century later, the salt tax in 1780 accounted for 22% of royal revenues (Touzery 2024). The salt tax varied across regions, along multiple tax borders – creating large discontinuities in tax rates, which we can exploit in our analysis. Because public goods provision was minimal and centred around royal prerogatives, such as national defence and justice, a higher tax burden did not correspond to higher redistribution.

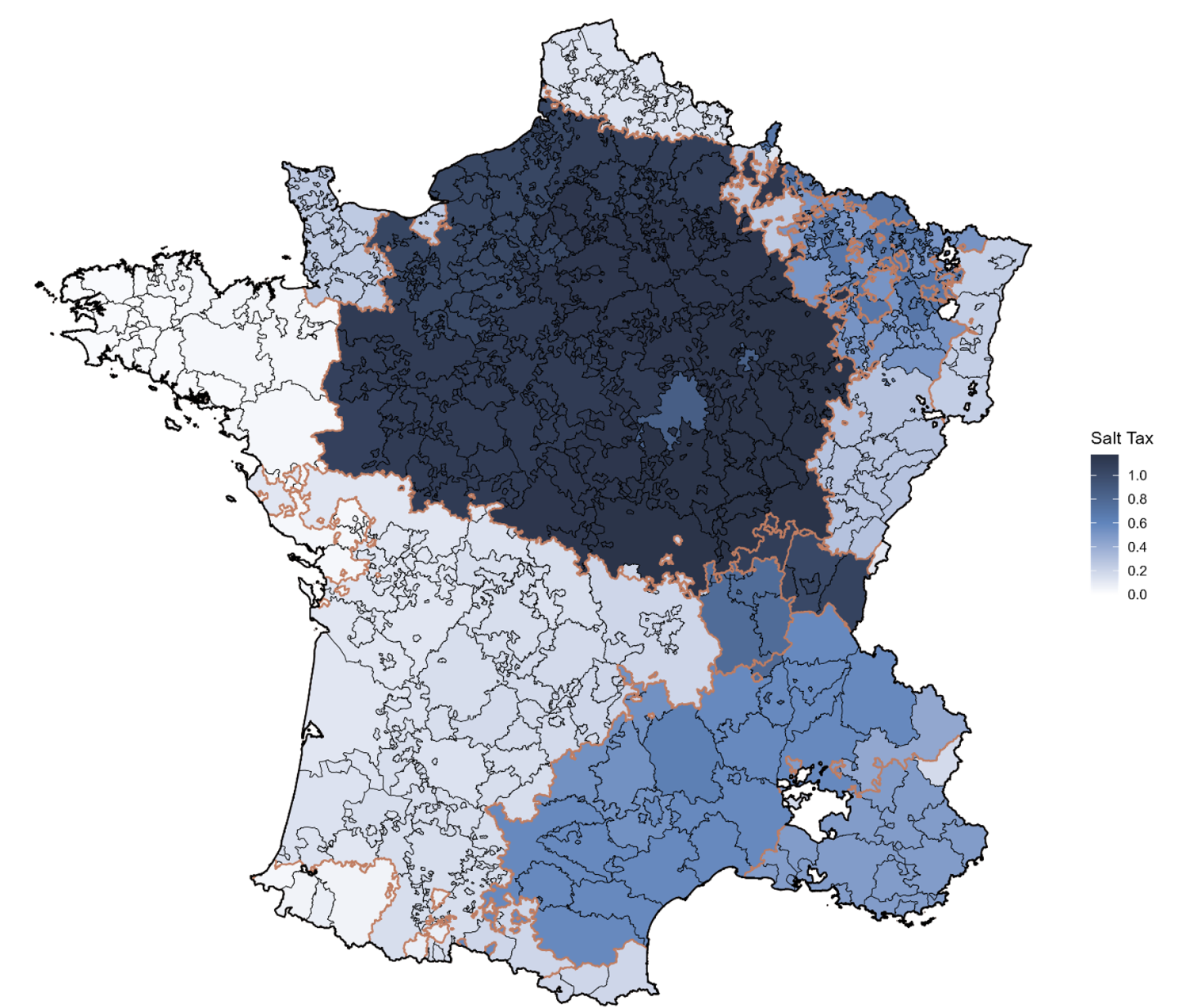

We retrieved and geolocalised data on all historical salt-tax borders from the digital archives of the National Library of France, which we cross-referenced with newly hand-collected information on the salt tax rate prevailing in each jurisdiction on the eve of the French Revolution. The resulting map is plotted in Figure 1 (darker shades of blue correspond to higher salt tax rates). We combine these data with a comprehensive dataset assembled by Chambru (2019) that provides a fine-grained localisation of uprising events before, during, and after the French Revolution.

Figure 1 Salt tax map

Notes: The figure plots the salt tax, expressed in pounds per litre, at the bailliage level, together with the salt-tax border highlighted in orange.

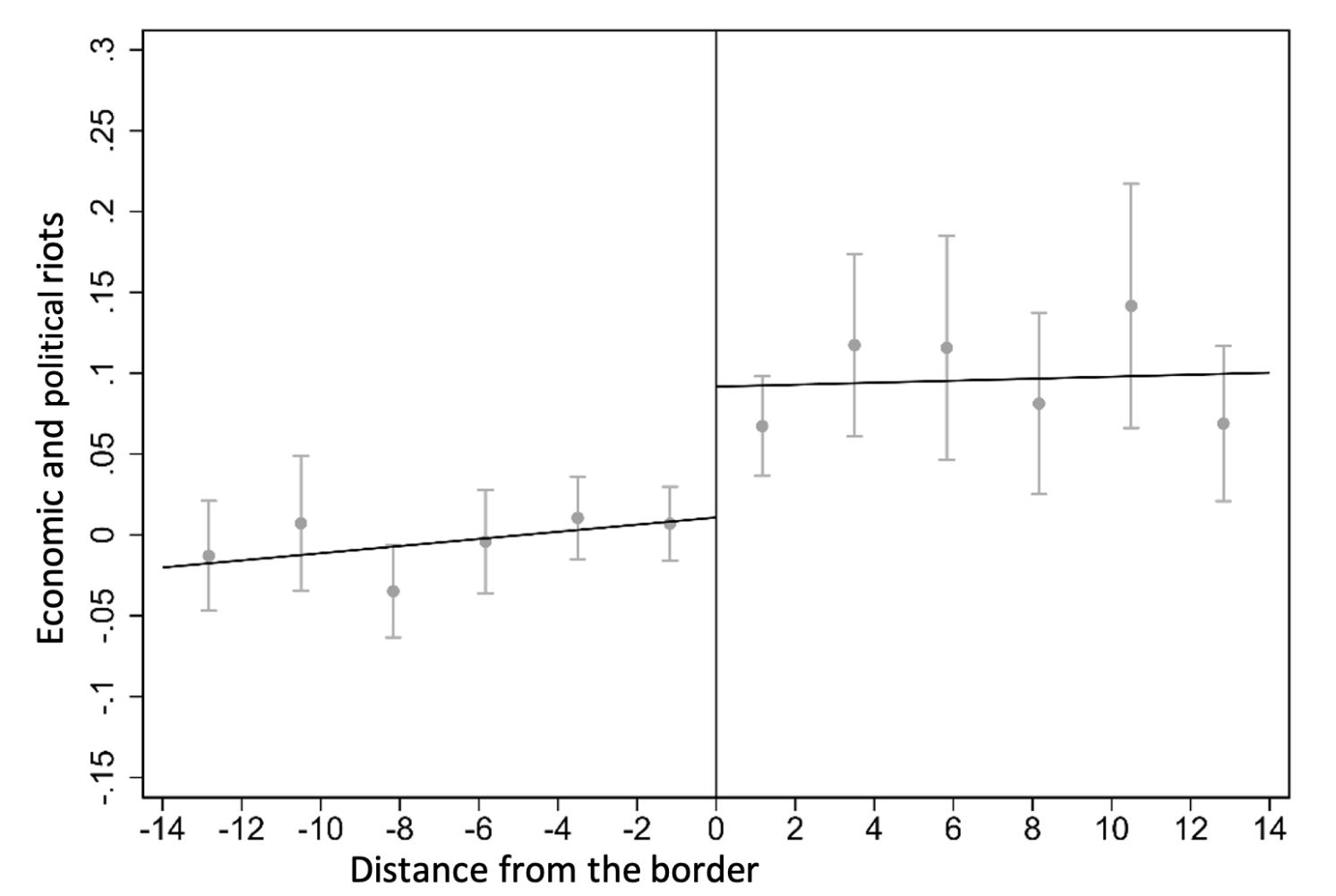

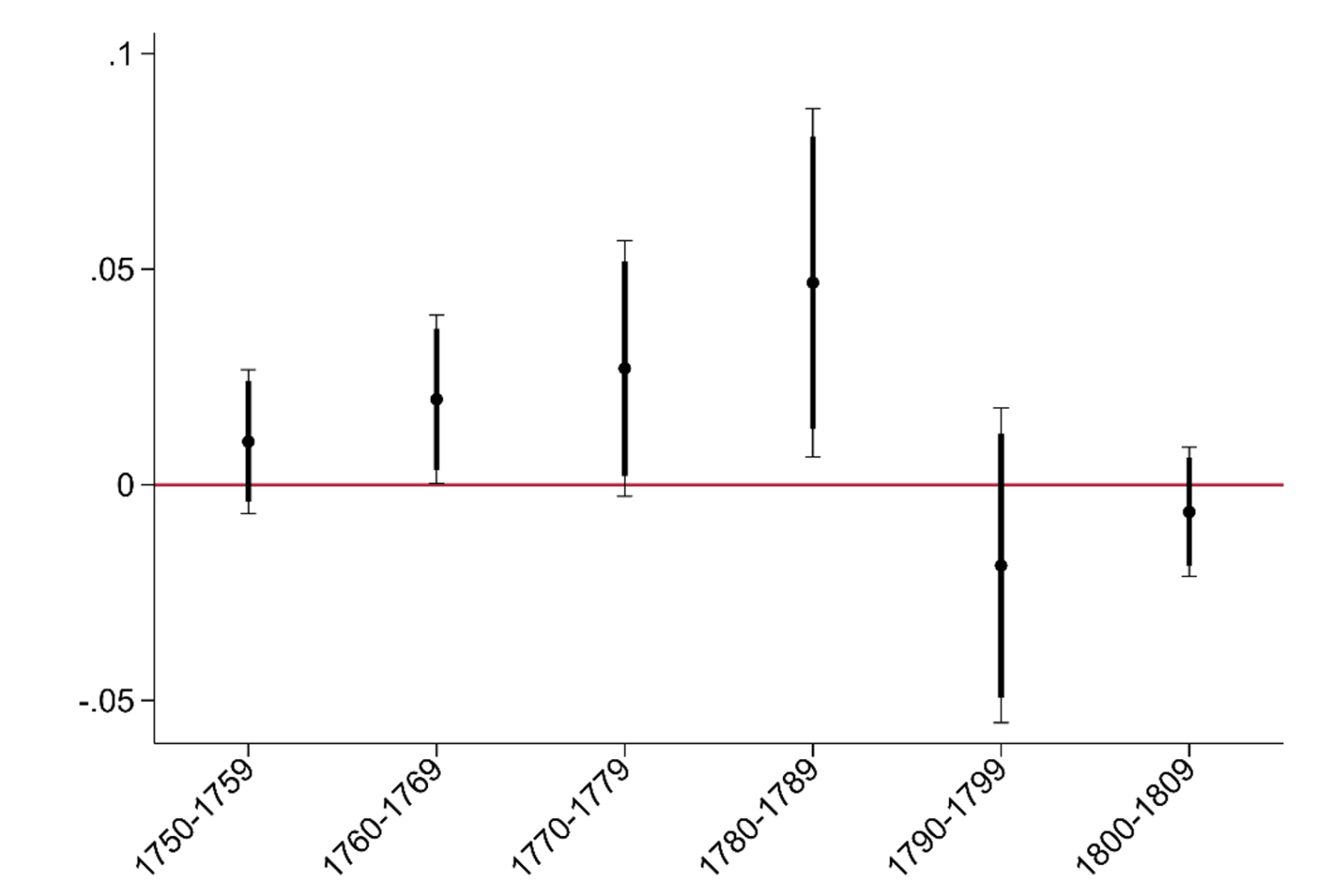

We deploy a non-parametric regression-discontinuity approach with optimal bandwidth and polynomial order selection following Calonico et al. (2014) around the salt tax borders. We find that crossing the salt-tax border leads to a discontinuous increase in the number of riots (Figure 2, Panel A). The effects of the salt tax begin to appear in the 1760s and grow over time, peaking in the 1780s (Figure 2, Panel B). According to our estimates, crossing the border from a low- to a high-tax municipality increases riots over the 1780–1789 decade by 73% relative to the sample mean. These effects are due to both the intensive (more riots in a given location) and the extensive (more locations experiencing at least one riot) margin.

Figure 2 Riots around the tax border

a) Number of riots, 1750-1789

Notes: The plot shows non-parametric regression-discontinuity estimates following Calonico et al. (2014) under optimal bandwidth and polynomial order selection. The dependent variable is the number of economic and political riots between 1750 and 1789. The treatment equals one for municipalities in the area with a higher rate. The specification includes border fixed effects as well as a set of municipal controls (population in 1780, coordinates, and soil fertility). The sample includes all municipalities in contiguous France, except those in the bottom quartile of the tax gap distribution. The coefficient is 0.104, and standard errors, clustered at the bailliage level, are 0.045.

b) Regression-discontinuity estimate, by decade

Notes: The plot shows non-parametric regression-discontinuity estimates following Calonico et al. (2014) under optimal bandwidth and polynomial order selection. The dependent variable is the number of economic and political riots for different periods of time (bins of 10 years). The treatment equals one for municipalities in the area with a higher rate. The specification includes border fixed effects as well as a set of municipal controls (population in 1780, coordinates, and soil fertility). The sample includes all municipalities in contiguous France, except those in the bottom quartile of the tax gap distribution. Standard errors are clustered at bailliage level.

The salt tax had been in place for centuries. Why, then, did its effects peak after 1780? Historians have pointed to several structural factors that heightened tensions during this period, such as the spread of Enlightenment ideas and the rising indebtedness of the French government. Historians and economists have also stressed how a series of droughts that hit France in the 1780s destroyed the harvest, increased wheat prices, and fuelled revolts throughout the country (Lefebvre et al. 1947, Waldinger 2024).

We conjecture that the eruption of discontent was stronger in places historically burdened by a higher salt tax, where weather shocks activated citizens’ frustration and opposition to the state. Combining our baseline regression-discontinuity analysis with temporal and spatial variation in growing-season temperatures, we confirm this hypothesis and show that droughts amplify the effects of the salt tax on revolts.

We then more directly connect our analysis to the French Revolution. We first test whether the salt tax favoured the spread of revolts across space and over time. We focus on the wave of riots that swept through France shortly after the storming of the Bastille, also known as the Great Fear. Between mid-July and early August 1789, rumours that the king sought to suppress the Third Estate triggered widespread violence that caused panic and led to the abolition of feudal privileges on 4 August 1789 (Lefebvre 1973). Exploiting newly geo-referenced data, we document that high-tax areas are more likely to host an initial revolt that was subsequently followed by many other riots. We also show that, during the Great Fear, revolts propagate more in high-tax areas.

Next, we verify that parts of France burdened by a higher salt tax express more complaints against the salt tax in the list of grievances collected by the king in the spring of 1789, ahead of the General Estates (Shapiro et al. 1998). We also collect data on newly elected members of the National Assembly (the legislature of the Kingdom of France from 1 October 1791 to 20 September 1792) and document that legislators representing areas subject to a higher salt tax are more likely to support the abolition of the monarchy.

Using newly digitised data on the votes cast in January 1793 by members of the Convention Nationale, 1 we further document that legislators originating from high-salt-tax regions are more likely to vote for the death penalty for the king. Comparing two legislators representing high- and low-tax areas, respectively, the former is 50 percentage points (or 79.5% relative to the mean) more likely than the latter to vote for the death penalty for the king.

The notion that extractive taxation was one of the main causes of the French Revolution is widely recognised in the historical literature (Marion 1921, Sands 1949, Touzery 2024). However, our paper is the first to provide systematic evidence in support of this idea. More broadly, our findings shed light on the relationship between taxes and revolutions and resonate with the well-known maxim ‘no taxation without representation’. While Angelucci et al. (2022) have documented how fiscal autonomy and local tax collection enabled medieval English towns to gain representation, our findings emphasise the risks of political exclusion: when taxation is imposed without representation, it can become a catalyst for popular unrest and regime change, especially following negative economic shocks.

See original post for references

They vote on that in France? We need that here, maybe as a ballot initiative.

Does anyone know how the vote came out?

Musical tribute (posted in Links a couple weeks ago with some lines in a different order):

GUILLOTINE

Parody of “Tangerine”. Info:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tangerine_(1941_song)

Frank Sinatra version (2:04):

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8V3larewcTo

Guillotines, for our kings and queens

And the oligarchs who rule behind the scenes,

Put the swords, to our overlords

With their hearts of coal and wealth beyond obscene.

Guillotine, when it slashes by,

All the peasants stare and rabble-rousers sigh

And I’ve seen, toasts to guillotine,

Raised in every bar from Texas to Racine.

Bridge:

Yes we have them all on the run,

For their heads belong to just one,

Their heads belong to guil-lo-tine!

They found him guilty with 683 to zero, and then voted on the punishment and:

It may have been the French taxation system that brought on the French Revolution as they simply could not get it together. For a contrast, the British reformed their tax system, fought several major wars and managed to pay their debts. The French were never able to do so, fought several wars and went broke. They knew about the British system but could never get in introduced into France. The French taxation system was extractive but only selectively so. The Nobles never had to pay any taxes and would oppose the thought of doing so. And it got worse. Under Louis XVI the rate at which certain people were being added to the Pension List grew at a rate faster than defense. And it wasn’t poor people being added to the Pension List.

That Salt Tax map may need another factor to be considered. The darker colours look like the old French heartlands including up to the coast where they fought the British for control over the centuries. But as one paper explained-

‘More “recently” absorbed territories such as Brittany, Burgundy, Provence, Artois (fifteenth century), Bearn, Foix, Bigorre (sixteenth century), Franche-Comte, and Flanders (seventeenth century) negotiated their global tax dues with the king through the provincial Estates, which met regularly and were charged with collecting tax monies.’

Macroeconomic Features of the French Revolution

http://piketty.pse.ens.fr/files/capitalisback/CountryData/France/Other/PublicDebtFR/SargentVelde95.pdf

So perhaps that salt Tax map should also be mapped against these ‘recent’ acquisitions over time.

I have the feeling that you are jumping the horse here a bit.

“For a contrast, the British reformed their tax system, fought several major wars and managed to pay their debts.”

Yeah, after a Revolution/Civil War caused by taxation issues. Thomas Hobbes mentions the fact in his “Leviathan”. The rise of the merchant class and their fortunes and their outrage at the royal taxes imposed on them…

And the funding of wars and the subsequent payment of debt it wasn’t that easy peasy. The story of Bank of England is pretty murky and for instance, the debt incurred for the Napoleonic Wars was repayied in full only 150 years later. And of course, the rich benefited…

I think by the 18th century that had worked it out. Think of the wealth used to fund the generational war against Napoleon, the funding of the Royal Navy all those decades to block the French and Spanish ports, the money and support given to foreign governments to prop them up and helping them to keep fighting, the money to outfit army after army to be sent abroad. You would think that in 1815 England would be prostrate & destitute but instead they quickly went on to expand the British Empire to all corners of the world. That paper that I linked to talks about the British system and how it compared to the French.

Rev Kev: You would think that in 1815 England would be prostrate & destitute but instead they quickly went on to expand the British Empire to all corners of the world.

In fact, the UK at this time, besides beating Napoleon, also burned down the White House in the US in the War of 1812; saw off the last of the Dutch empire; had the Industrial Revolution; and, if you want to close this period at 1839, sent two Royal Navy ships to sink 29 Chinese warships and kick off the First Opium War, which ended in China ceding Hong Kong to the UK.

Simultaneously, the Royal Navy West African squadron was shutting down the Transatlantic slave trade — it was a massive effort costing 3% of British GDP — and doing whatever else the British were doing in India, Africa, South America, and Australia.

The interesting thing if if you look at the figures is that it was so much an maritime empire that the British army was strikingly small — and disliked and distrusted by the general British public after it was used at Peterloo to put down the Chartists — so that it needed to bulk up for the Napoleonic Wars and WWI.

Thus, forex, the British ran India with only 3,800 British administrators and sepoy armies, and their colonies elsewhere in Asian, the ME, and Africa with armies largely drawn from the native populations under British officers, and, of course, used Hessian mercenaries in the American Revolutionary War.

So you are saying it took over 100 years to work it out, eh?! Still at the cost of a bloody civil war/oligarchic revolution, etc.

The point remains, the title could be used to write an article called Taxation and the English Revolution, no?!

Good idea.

The English Civil War had a very large impact, down the ages.

The Bank of England has run a debt pretty much continuously since 1694 and this reached £850m in 1815. Bank surpluses have been rare events.

Like many UK banks it was established to fund the Atlantic Slave Trade cash flows and channeled foreign investments and their profits into trade and the industrial revolution.

The British Empire’s territorial maximum was in 1920, with the final expansions in Africa actually post WW1. Wealth extraction (or profiteering, depending on your point of view) from the colonies, and especially slavery, had initially funded the Industrial Revolution but continued to supply much of the UK’s wealth and hence capacity for wars.

However, there was continuous destitution during that period, including the 1840s famines and Highland Clearances, and then during the 1870s economic slump down to policies at that time, arguably laissez faire considerably worsening that depression, as well as wider global events.

Life expectancies during the Industrial Revolution were such that Manchester as an industrial centre at the time of Peterloo actually had lower lifespans than the rural areas from which migration fed its growth – with the push for that from the major rural poverty created via the Enclosure Acts. So urban destitution was prominent throughout the 19thC, but it was the working class that was prostrated.

“Like many UK banks it was established to fund the Atlantic Slave Trade cash flows and channeled foreign investments and their profits into trade and the industrial revolution.”

In fact, the purpose and scope of the Act establishing the Bank of England that received royal assent on the 25 April 1694 was to fund the War against France as was clearly stated in its title: “An Act for granting to theire Majesties severall Rates and Duties upon Tunnage of Shipps and Vessells and upon Beere Ale and other Liquors for secureing certaine Recompenses and Advantages in the said Act mentioned to such Persons as shall voluntarily advance the sūme of Fifteene hundred thousand pounds towards the carrying on the Warr against France.” [5 & 6 Will. & Mar. c. 20]

The Act meticulously detailed the rates to be charged upon “the tonnage of ships and vessels importing goods and merchandise through English ports and excise duties to be levied on beer, cyder, vinegar, brandy and mead,” with rates dependent on the place of origin for the goods or the location of the brewery. [https://www.magicmoneytree.org/2020/04/the-bank-of-england-by-ways-means-1694.html]

Yours,

AH

Regardless, the Bank of England, like Lloyds of London, Barclays etc., was essential in sustaining the Atlantic Slave Trade and processing profits.

Of course the BoE was also influential, even instrumental, in suppressing the Darien scheme, so yes it did have a wider political purpose from the outset, and not just France.

Regardless!

The BoE was established in 1694 as a financial credit institution to facilitate the raising of loans for the Crown so it could carry on a war with France for global colonial supremacy; a war that would continue, with short interruptions, until 1815. The Act integrated and, in essence, “guaranteed” the loans through the already existing Navigational Act of 1650. By the 1690s, the Navigational Act had become the basis on which the British Merchant Marines was built and its enforcement lead to global British Naval and Commercial supremacy.

When in 1793 the French Navigational Act was pushed through the National Conventional by Bertrand Barère and Gaspard Ducher, it’s purpose was to obstruct British trade from entering Europe through the Free Ports operating on territories formerly under the jurisdiction of the Bourbon Regime and now nationalized under the Republic. The French Navigational Act was an attempt to undermine the British Commercial System and its financial institutions. In the early 1800s, Barère was asked by Napoleon Bonaparte to construct a plan to further obstruct British Trade with Europe, which lead to the elaboration of the Continental System.

Given this, you are correct, the British banks also sustained the Atlantic Slave Trade as well as the plantations and monopolies of the East India Company at the behest of the British ruling elites by processing their profits.

AH

This is very interesting stuff but the duplicity of the English crown was such that the intent in the creation of the BoE in pursuing wider trade objectives, whatever the claimed initial loan guarantee goal, was not going to be directly advertised in any enabling legislation.

The contemporaneous denial of the sabotage of Darien, when the English even feared competition from the Scots, (who were pally with France anyway) let alone other continental nations, is a typical example of this diplomatic approach, rooted in mercantilism.

Yes, the crown needed to fund war, and guarantee loans, but an essential purpose of the English banking system, at that time and for much of the 175 years thereafter, was primarily colonial trade expansion, and the Atlantic slave trade was largely funded through their activities, with the profits then providing capital for much subsequent industrial development and then its growth, from the mid 18thC onwards.

Just as the USA subsequently did, the UK was highly protectionist in terms of tariffs during that period, only becoming committed to free trade once its infant industries were well established. Ha-Joon Chang’s ‘Bad Samaritans” is very apposite in looking at 47s current mindset.

In the spirit of explaining the differential salt taxes, it’s apparent that the salt tax rates on the map were lower in the western coastal areas, which are where France produced the salt and where I imagine the local population would have been able to evade the tax anyway by physical access to salt production. Further, of course France would want to start taxing salt consumption in the late middle ages since it doubled as an export product per Anton Howes. https://www.ageofinvention.xyz/p/age-of-invention-the-dutch-salten

The system became far more extractive because of the financial ruin which more than a century of war had visited upon France (chiefly due to the need to settle the north-eastern border and to forestall ‘encirclement’ by the Habsburgs and their proxies or legatees): https://global.oup.com/academic/product/the-financial-decline-of-a-great-power-9780199585076?cc=gb&lang=en&

Britain, under William III and his successors, frequently led the charge against France and underwrote the cost of its allies (notably the Habsburgs themselves), and so financial innovation was driven by necessity, given Britain’s much more slender resources. This remains the best single account of the process, led chiefly by Godolphin, Halifax, Lowndes and Henry Pelham: https://www.taylorfrancis.com/books/mono/10.4324/9781315239668/financial-revolution-england-dickson (the late Peter Dickson also wrote the definitive study of the finances of the Habsburg lands under Maria Theresa).

Your remarks about the regional application of the gabelle are interesting, not least because the map in the article shows the most oppressive levies covering most, though not all, of the jurisdiction of the parlement of Paris (with whom successive Bourbon monarchs were frequently at loggerheads), whilst the lightest levies were in the jurisdiction of the parlement of Rennes. Might this explain why the counter-revolutionary rebellion in the Vendée in 1793-96 had such extensive popular support?

Yeah, to your point about the Nobles this article strikes me as odd in its silence about who was NOT taxed — isn’t this “inequality” of taxation itself a function of whose interests are “represented” and whose are not?

And it’s arguably the state’s failure to tax the Nobles which leads both to the imposition of crushing tax burdens on the poor and the state’s chronic fiscal problems, since the rich were the class denying the state access to sufficient resources which only they held (primarily in the form of land and land rents).

OP: The notion that extractive taxation was one of the main causes of the French Revolution is widely recognised in the historical literature (Marion 1921, Sands 1949, Touzery 2024). However, our paper is the first to provide systematic evidence in support of this idea.

I’m not sure systematic evidence was necessary, though this data is interesting. How systemic was tax farming — parasitic taxation by elites — in Pre-Revolutionary France? This systemic —

Wall of the Ferme générale

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wall_of_the_Ferme_g%C3%A9n%C3%A9rale

…Unlike earlier walls, the Farmers-General Wall was not intended to defend Paris from invaders but to enforce payment of a toll on goods entering Paris (“octroi”). It was commissioned by the nobleman and scientist Antoine Lavoisier on behalf of the Ferme générale (General Farm), a tax farming corporation that paid the French State for the right to collect (and keep) certain taxes. Lavoisier was a shareholder and Administrator of the Ferme générale and determined that the cost of building, staffing, and maintaining the wall would be compensated by better revenue collection. The wall’s tax-collection function made it very unpopular: a play on words of the time went “Le mur murant Paris rend Paris murmurant” (“The wall walling Paris keeps Paris murmuring”)There was also an epigram:

Pour augmenter son numéraire (To increase its cash)

Et raccourcir notre horizon (And to shorten our horizon),

La Ferme a jugé nécessaire (The Ferme générale judges it necessary)

De mettre Paris en prison (To put Paris in prison).

The Wall was five meters high and 24 km long, following the then-boundaries of the city of Paris. No buildings could be erected within 98 meters of its exterior or within 11 meters of its interior. The outside of the wall was flanked by boulevards….

Me: It was a big, beautiful tariff, in short.

The wall is in a scene in Eric Rohmer’s The Lady and the Duke (L’anglaise et le Duc), which I highly recommend for its portrayal of the Revolution and Terror unfolding, sometimes almost in the background. Rohmer is a conservative and here somewhat reactionary. The French critics did not like it but then they wouldn’t, would they.

Worth mentioning the Great Hedge of India — set up by colonial authorities to mark a customs border for the taxation of… salt.

vao: Worth mentioning the Great Hedge of India — set up by colonial authorities … for the taxation

Thanks. Interesting.

As you may know, archeologists and anthropologists today believe the first Mesopotamian walled city-states in the third millenium BC and China’s Great Wall in the seventh century BC were constructed to keep those states’ subject populations inside those walls, producing surpluses — grain and wealth — for the elites there, as much as to keep enemies out.

Ironically, the main progenitor of the hedge, A. O. Hume (son of the great radical parliamentarian, Joseph Hume) was one of the founders of the INC.

I’m curious to see if Alexis deTocqueville’s the “Ancien Regime” will be mentioned. He asserts the theme of continuity of an increasingly centralized and powerful state between the pre- and post-revolutionary eras. A difference between the inequality of pre-revolutionary France and us now, is that the French were intensely angry about hereditary and institutional inequality. So far, although there is grumbling, there is little serious popular push back against inequality. In fact, inequality, in America is excused and even justified as necessary for the economy.

It seems to me that poverty is the worst fear of Americans. Even the poor see those who have less than they do and live in fear of greater poverty.

‘The Nobles never had to pay any taxes and would oppose the thought of doing so.”

I see a parallel to the oligarchs in the USA passing their projected 68 trillion dollars on to their heirs in the coming 20 years and paying little taxes. They will exert an even greater influence on government which will only further widen the gaps between they haves, almost have and have nots.

As G.K. Chesterton pointed out. “The poor have sometimes objected to being governed badly; the rich have always objected to being governed at all.”

The Church also didn’t have to pay taxes. IANAH(istorian)… The nobility and the Church together owned most of the land and most of the wealth, leaving the rest of the people to pay the whole of the tax.

There was also a forced labor law, which required local governments to provide labor and materiel (again, nobles and church were exempt) to maintain roads and canals whuch further extracted time and resources from the local populations.

Now add widespread famine atop that and riots happen. IIRC there was a military adventure in there that added conscription to the already volatile mixture.

Maybe an actual historian can confirm or correct me. Those events and what is happening in the US now might rhyme. I’m afraid that we won’t know until confirmed by bloodshed.

Just to add some data to this presentation.

For decades, French anthropologist Emmanuel Todd has been studying family systems and their impact on political mentalities. One of the numerous family types he identified is the nuclear egalitarian family, which, at the end of the 18th century had had for centuries an extremely egalitarian view of the status of its members: thus, all children, male and female, in principle inherited the same share of their parents’ legacy.

You can see a map of European family systems from Wikipedia. In France, the region where the nuclear egalitarian family historically dominates is also the one whose population drove the French revolution.

Compare it to the salt tax map (figure 1 above): this is pretty exactly the region where the salt tax was the highest. Hence, there is a significant confounding factor not taken into account in the analysis.

Because the regions where the salt tax was higher were also those inherently more averse to the sheer inequity imposed by then social system, the following statements cannot be considered as a strong evidence of a correlation between “high salt tax” and “opposition to the Ancien Régime” without a more refined analysis (just replace “high salt-tax area” with “sociologically egalitarian area” to see the point):

“crossing the border from a low- to a high-tax municipality increases riots over the 1780–1789 decade by 73% relative to the sample mean.”

“high-tax areas are more likely to host an initial revolt that was subsequently followed by many other riots.”

“parts of France burdened by a higher salt tax express more complaints against the salt tax in the list of grievances”

“legislators representing areas subject to a higher salt tax are more likely to support the abolition of the monarchy.”

“legislators originating from high-salt-tax regions are more likely to vote for the death penalty for the king.”

It is probable that the relative level of taxes had an impact, but there was also an ideological/mentality factor intrinsincally linked to regional sociological configurations (derived from family structures) — configurations that are by now well-studied, but ignored by the authors (they being economists, I am not entirely surprised about that). A deeper investigation is required to untangle the contribution of those two factors and determine their relative importance.

Good point, vao. An implication would seem to be that egalitarian family structures shaped community power structures. Is that accurate?

I cannot answer. Perhaps the works of Emmanuel Todd & others may provide insights at that level of detail.

I’m disappointed that this article doesn’t explain the REASON for the salt tax and other extractive taxes. The reason was to pay rising war debts (many of which the Revolution wiped out).

A similar phenomenon occurred in Britain. Kings needed parliamentary approval for “normal” taxes on income and property. But by the 14th century, merchants explained to them that kings did NOT need parliamentary approval for excise taxes. So Edward and subsequent kings raised money to pay their bankers by creating a monopoly on England’s wool trade.

Other kings followed suit in order to bypass parliamentary controls. Hence, France’s salt tax.

You do have to wonder what the people that lived near the French coastline did. All that free salt. Come to think of it, the British imposed a Salt Tax in India – which helped spark the Indian Independence movement. And this led to Ghandi’s Salt March-

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Salt_March

https://www.britannica.com/topic/ship-money

Ship money, in British history, a nonparliamentary tax first levied in medieval times by the English crown on coastal cities and counties for naval defense in time of war. It required those being taxed to furnish a certain number of warships or to pay the ships’ equivalent in money. Its revival and its enforcement as a general tax by Charles I aroused widespread opposition and added to the discontent leading to the English Civil Wars.

Is there data about the distribution of inequality? GINI indexes of the different regions, or something like that.

The gabelle or salt tax was very unevenly applied and implemented across regions. The Wikipedia article on the gabelle explains this quite well. A lot of smuggling followed from the regional disparities in the price and cost of salt.

The crisis of the French Revolution arose from state bankruptcy, which was less about tax revenue per se than about inefficient collection. The immediate issue presented to first the Assembly of Notables and the the Estates General was getting consent for broadening the tax base to include the wealthy and privileged and church properties.

Another big problem was that France lacked a central bank, or really anything like a domestic banking system. The Crown was dependent on Swiss and Dutch bankers in Paris.

“The Crown was dependent on Swiss and Dutch bankers in Paris.”

Ah yes, I alluded to this in two comments here and there.

If you want a much much deeper dive, and you’re into podcasts, the Revolutions podcast has like 50 ~ 35 minute podcasts about the French Revolution, it’s like season 3 or 4?

It would take a revolution. One problem is that the US is under a one party dictatorship. If one doesn’t think that a POTUS like Trump couldn’t round up 500,000 ICE ala Brown Shirts or SS; by giving them a badge, a mission, an identity, a gun, a salary, & power; think again, they will come. For an opposition party to arise, it would require the Democrats to reinvent themselves by dropping: the old guard, the supporting oligarchs, the neocons, and the fianaciers of Wall Street and offering a program that addressed the need of , say, 60 to 90% of the people in the US , i.e. the working class , instead catering to the 1%. Address fair opportunity, real affordable health, improved infrastructure, and better education for starters. As it is, the people in the US seem to be content being indebted wage serfs or dreamers speculating on making million in bitcoin. This is not the fodder for a revolution.

I think the working class threw in the towel a good 30 years ago. It’s been clear, for a long time, that the Democrats were no longer interested in them. Indeed, they have now morphed into ‘deplorables’ who should be shunned. I sometimes wonder if all that fentynal flowing into desolate areas, like Youngstown Ohio, is intentional.

Fentanyl, intentional? Wouldn’t be the first time.

As Peter Coyote sang at the Whole Earth Jamboree in 1978: “Now their selling my kids the fifties again in every kind of way / As if they were afraid of what the kids just might invent today / They’re not telling ’bout zip guns and gang attacks / Or how the heat cooled it all by giving out smack [= heroin] / They’re greasing that away / I heard a crazy lady say.”

Source: pages 117–118 here:

https://wholeearth.info/p/coevolution-quarterly-whole-earth-jamboree-1968-1978

The reason French taxation scheme was uneven had to do with the legacy of feudalism: there were all sorts of privileges that could not be removed without consent of the privilege holders. These were not just class dependent: they were, for example, granted as part of the deal in which a region accepted direct rule by the French king. So the taxation wound up falling heavily on the regions that, for some reason or another, could not get such a good deal centuries ago.

Incidentally, this was actually considered a serious problem even (or, especially, really) by the royal government: there were many attempts, especially during Louis XIV’s reign, to find legal loopholes to tax even privileged regions and classes–it was not actually true, for example, that the nobles did not pay taxes–they just paid “other” taxes, created via these loopholes. But it still meant that the French tax scheme under the monarchy was a complicated mess–too many loopholes, loophole busters, and secondary loopholes. (Being a tax lawyer in pre Revolutionary France would have been–and I think it actually was–very lucrative business) The political crisis that preceded the Revolution should be seen in this context, with the king’s advisors trying hard to shift the tax burden to the privileged folks while these attempts were resisted (successfully) by those who were privileged in the name of liberty and all that–obviously, things turned out a bit differently when the dust cleared.

This goes directly to the argument Tocqueville made about the Revolution: it allowed the French state to create a more uniform system of administration (including taxation), which French kings wanted to accomplish for centuries. This is a little different from the popular perception of the kings, “nobles,” and the “bourgeoisie” in course of the Revolution.

Well, circumstances might be similar but there are many other factors that “pacify” the population: Netflix, digital surveillance and enhanced repression apparatus, being sold on a dream to get rich rather than have a fair society…

Reminds me of my favorite Steve Biko quote:

“The most potent weapon in the hands of the oppressor is the mind of the oppressed.”

https://africacheck.org/fact-checks/meta-programme-fact-checks/yes-mind-oppressed-quote-south-africas-steve-biko

Interesting how long a shadow the past can cast. The area of heaviest taxation seems to centre on the Ile-de-France, which was the original power base of the Capetians when they took the throne in the tenth century.

Also, in the fourteenth century, during the Hundred Years War, the French Crown had great difficulty imposing its authority on the furthest-flung parts of France because of the distance from their main power base. So the English were able to stir things up in Gascony, Brittany, Flanders taking advantage of local resentments towards the centre. These areas appear to be relatively lightly salt-taxed four hundred years later. And of course Alsace-Lorraine was a recent acquisition.

I wondered if anyone was going to mention de Tocqueville. IIRC it is all pretty much in there. Great historian.

Tocqueville’s insights have been making a big(gish) comeback not too long ago in making sense of how political institutions evolve, but without making much impact outside certain niches. What was it that AJP Taylor said about Tocqueville? Daring thinkers don’t make good policymakers? (wrt Tocqueville’s tenure as, I think, the foreign minister)

The issuance of Assignat currency coincides perfectly with the start of the French Revolution, it was quite similar to our Continental Currency efforts of a decade or so prior, with the difference being we had no official specie in circulation, whereas France did.

It became a race to the metal exits…