Yves here. This post is useful by virtue of giving some detail on how the Smoot Hawley Act made the Great Depression worst. However, it also takes an absolutist view against tariffs, when some well-regarded development economists like Dani Rodrik would beg to differ with some of its claims. In the last 15 years or so, this cohort has argued that tariffs are beneficial to less advanced economies when implemented so as to protect certain industries so they can get to be big and efficient enough to have a hope of competing in world markets.

It is also worth noting that non-tariff trade barriers can be very effective….and hard to curb. The poster child is Japan in the 1970s and 1980s. Aside from the difficulty of navigating a very fragmented distribution system serving as an impediment to foreign vendors, at least as big an obstacle was the strong Japanese preference for Japanese products. They regarded US wares as inferior, and the proof went beyond cars. I would see Japanese women in stores turn garments inside out to count the number of stitches per centimeter, and American clothing fell short.

The Plaza and then Louvre Accords demonstrated the doggedness of these preferences. The Plaza Accord was G-5 agreement to engage in coordinated currency manipulation to increase the value of the yen v. the dollar. The program succeeded too well, leading to a big overshoot in the value of the yen, resulting in the Louvre Accord to bring the yen back down.

The US expected the Plaza Accord to reduce the level of Japanese imports into the US, particularly cars, by virtue of making them more expensive, and also increase US exports to Japan because, conversely, their price would be lower.

While Japanese exports to the US did indeed drop meaningfully, US exports to Japan barely budged.

By Deniz Torcu, Adjunct Professor of Globalization, Business and Media, IE University. Originally published at The Conversation

Imagine waking up in 1932, in any US city. Upon ordering your morning coffee, you realise that its price has doubled since last year. This isn’t because of a coffee shortage, but rather because new trade barriers have caused the price of importing Colombian coffee beans to shoot up. The same thing has happened to sugar, tea and cocoa. Everyday items have suddenly become a luxury.

This dramatic change stemmed from one of the most harmful decisions in modern economic history: the Smoot-Hawley Act, enacted in June 1930. This law, championed by senator Reed Smoot and congressman Willis C. Hawley, aimed to safeguard US agricultural interests in the wake of the 1929 stock market crash.

However, pressure from industry lobbies meant it quickly expanded to cover over 20,000 products, including manufactured goods. Tariffs averaged around 40%, but in some cases were as high as 100%.

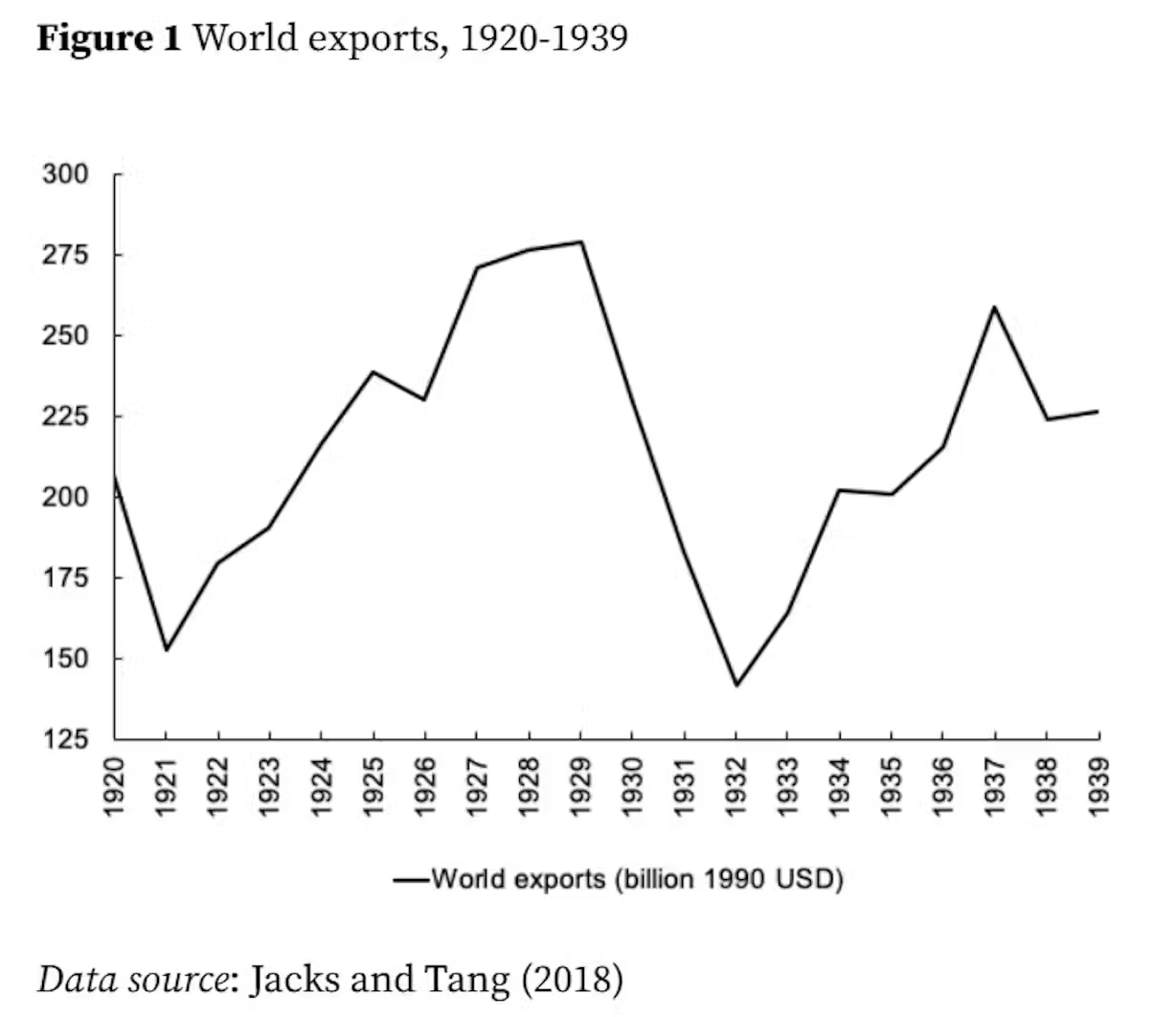

Far from helping the economy, this measure contributed to the collapse of international trade, as countries like Canada, France, Italy, Germany and the UK imposed harsh retaliatory tariffs on on US products. This set off a chain reaction: international cooperation weakened, US exports fell by 61% between 1929 and 1933, and global trade shrunk by over 60%.

This further aggravated the Great Depression. It hit economies who depended on international trade especially hard, and exacerbated geopolitical tensions throughout the 1930s.

Skyrocketing inflation, mass job destruction and falling living standards became stark testaments to protectionism’s failure. The contraction of global trade not only crippled key industries, but also destabilised entire economies that depended on exports to sustain growth. Currencies were devalued, deficits soared, and financial systems collapsed one after the other.

The 1930s therefore witnessed not only an economic crisis, but also a transformation of the international system fuelled, in part, by misguided political and trade decisions. This historical lesson, as the current case of Trump’s tariffs demonstrates, continues to be ignored by leaders who prioritise short-term populist measures over global economic stability.

Why Do Tariffs Fail?

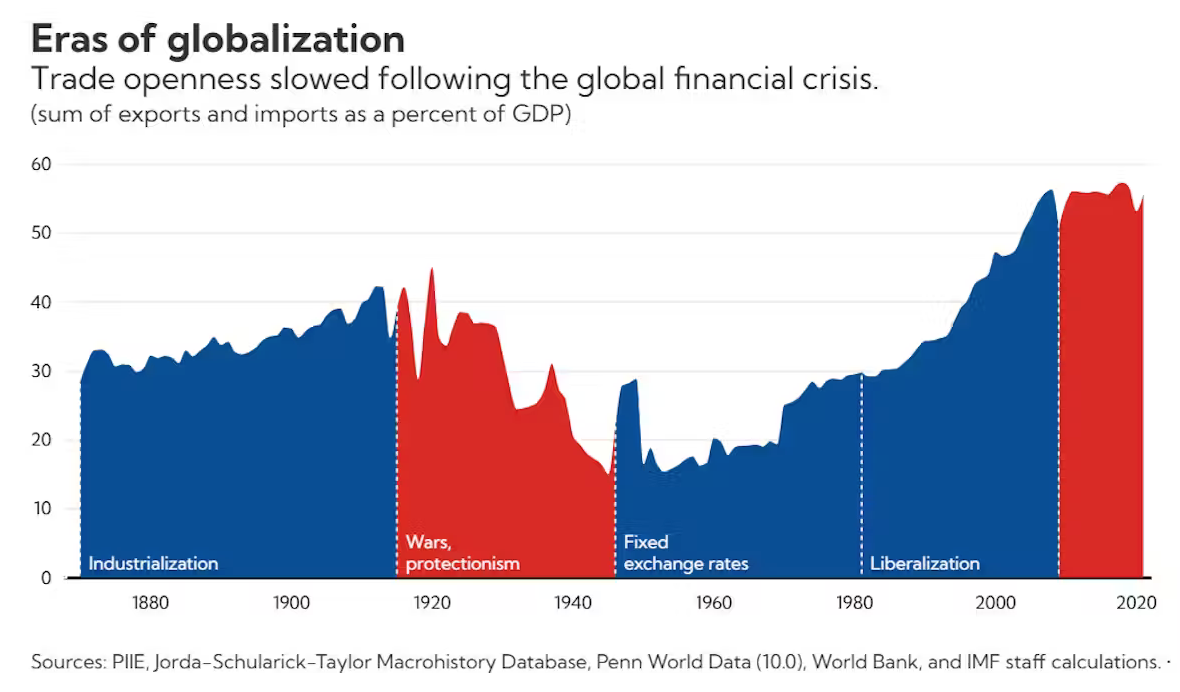

After decades of progress in trade liberalisation – driven by multilateral organisations like the World Trade Organization, the United Nations and the OECD – it seemed that lessons had been learned. However, Donald Trump’s second presidential term has revived disturbing parallels with Smoot-Hawley.

Historical and contemporary evidence clearly shows that tariffs rarely function as an effective tool of economic protection. In an interdependent global system, supply chains cross multiple borders before reaching the final consumer. Higher tariffs raise production costs, hurting both consumers and businesses, even in the countries that implement them.

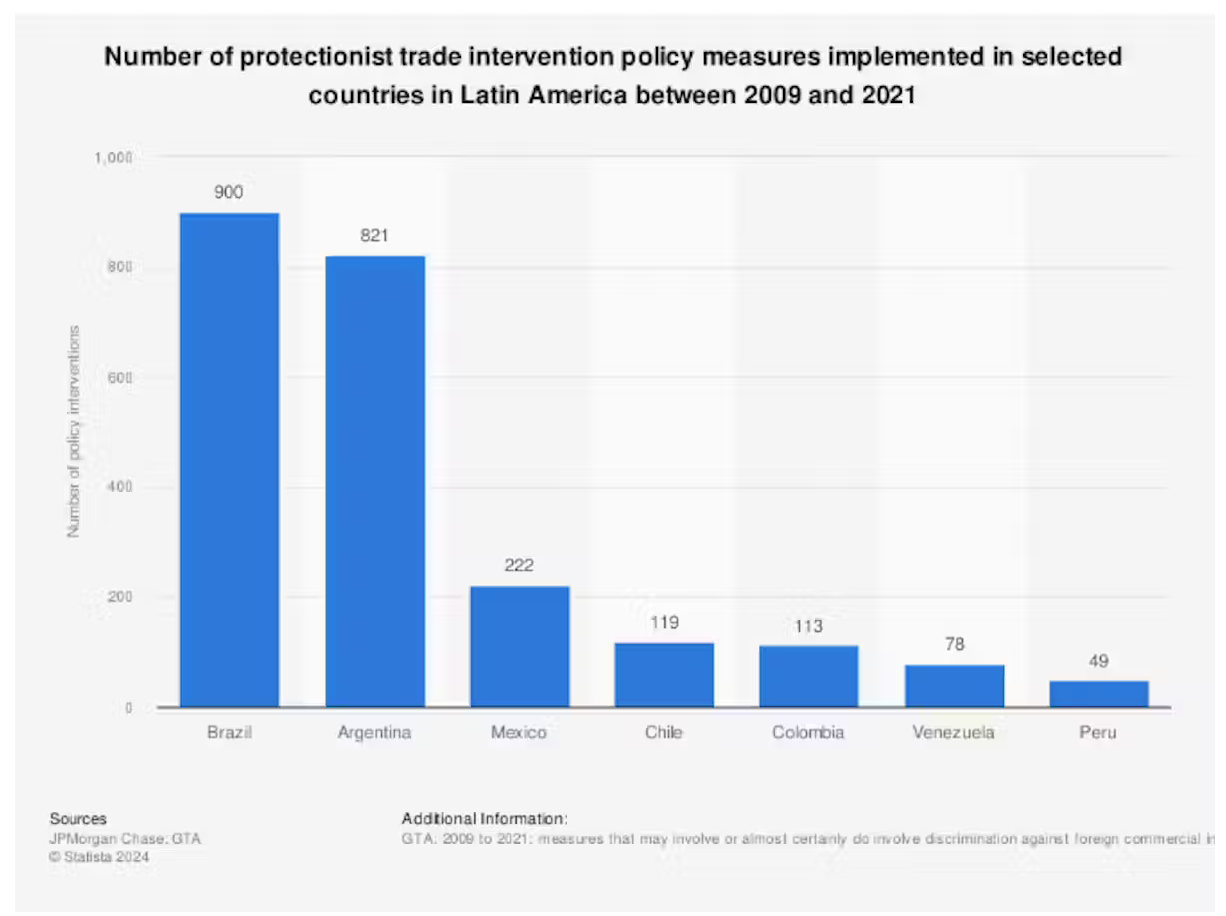

In addition to the US, other countries have also felt the adverse effects of protectionism. Argentina, for instance, implemented an import substitution policy with high tariffs and trade restrictions for decades. Although it initially stimulated industrial development, in the long run it led to a loss of competitiveness, high inflation and dependence on the state to prop up inefficient sectors.

Brazil had a similar experience in the 1980s and 1990s. Its tariff barriers temporarily protected certain industries, but also reduced product quality and stifled technological innovation.

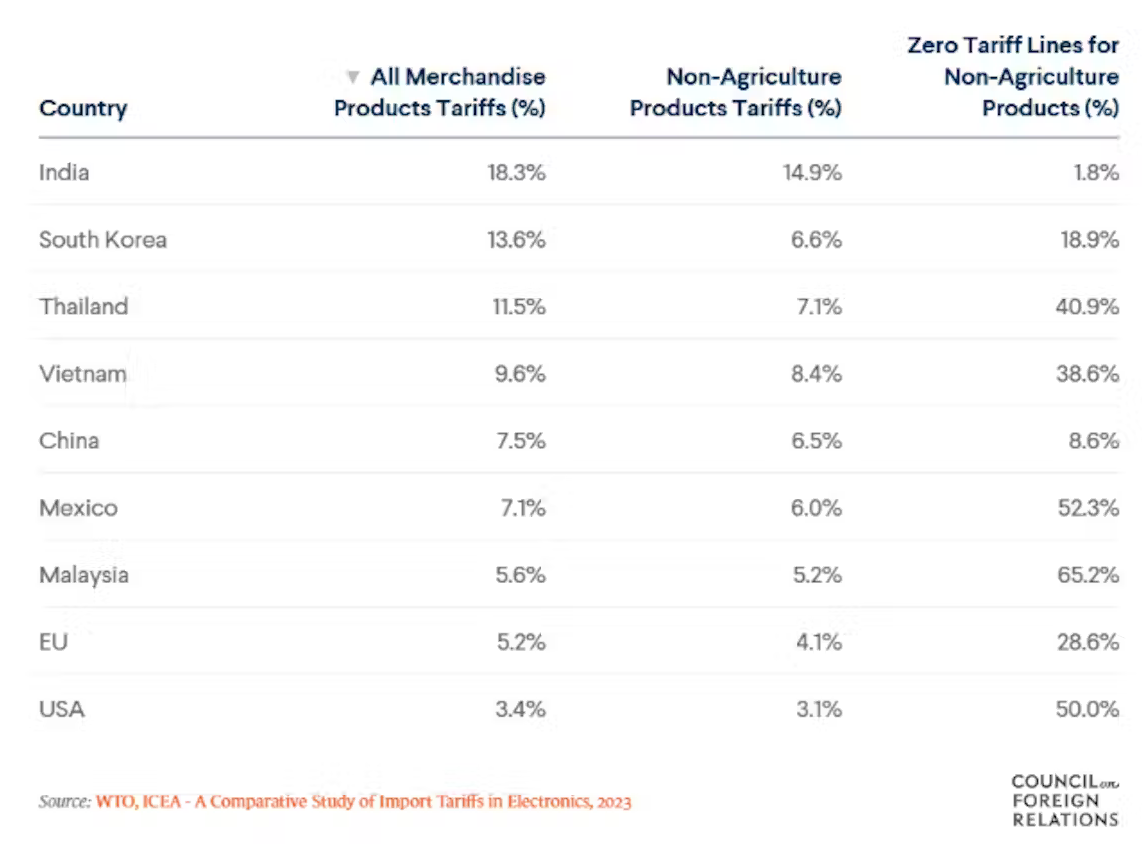

Until its 1991 economic reforms, India had one of the world’s most protectionist tariff regimes, which limited its integration into global trade and slowed its economic growth.

From these examples we can see that protectionism often causes a chain reaction of negative, escalating impacts:

- Rising prices for consumers

- Loss of economic competitiveness and job destruction

- Reduction of global economic growth due to uncertainty and diminished international trade.

Making Economies More Cooperative and Resilient

From the Smoot-Hawley Act to Trump’s current trade war, economic history clearly demonstrates that protectionism is not only ineffective, but counterproductive. In a world where value chains are global and innovation depends on transnational cooperation, closing economic borders weakens collective resilience.

Protectionism may seem like an immediate solution to economic crises and domestic pressures, but its long-term consequences are almost always more costly than its apparent benefits. Instead of strengthening domestic industries, it isolates them. Instead of protecting jobs, it destroys future opportunities.

The aforementioned cup of coffee in 1932 became a symbol of an economy locked in on itself. In 2025, it could be electric car batteries, medicines or basic foodstuffs that remind us of the high cost of negatively interfering in global trade.

Now more than ever before, international cooperation, market diversification and investment in sustainable competitiveness are the only smart way forward.

o many things went wrong or broke down in the early 1930’s… bursting property/credit bubble; localized collapses of the banking payment system; mass financial, commercial & industrial insolvency; collapse in trade and production… it’s difficult to say what caused more damage to the economy. The Smoot-Hawley Act is just one of those pieces.

A key thing that should have been learned is that actions have consequences and often unplanned consequences. As Yves pointed out the Plaza Accord was successful in reducing the Japanese exports to America, but it also led to extremely low interest rates in Japan which is often said to have been the fuel thrown onto the already growing property bubble fire that eventually caused Japan’s lost decade.

The Trump administration is breaking so many things all at once that it will only be a matter of time before the unplanned consequences reek real havoc and I doubt they have the brainpower or care enough to be able to react in time before real economic and or social chaos takes over.

Trump’s in a hurry. He has got to have everything done and preferably irreversible by November 3d, 2026. On that date you have the US Midterms and the way that things are going, support for the Republicans may very well collapse big time putting the Democrats in charge of Congress. For him the clock is ticking.

Monetary policy impacts during the Depression era would be interesting to review relative to tariff impacts.

As Hegel said, “the only thing men learn from history, is that they learn nothing from history”…the selfishness and greed of humans is no different fromt hat of governments or institutions…there will always be tariffs and protectionism, in fact, look for new versions of it as the US slowly collapses….

One thing completely different from the Great Depression is the idea that there was literally no money* available to much of the population in a decidedly deflationary period versus now where manna flows like honey, albeit with inflationary pressures up the yin yang.

How scarce was money?

No Dimes minted in 1932 and 1933

No Quarters minted in 1931 and 1933

No Halves minted in 1931 and 1932

No Dollars minted in 1929, 1930, 1931, 1932 and 1933.

* in the book The Great Depression-A Diary the diarist related that he could buy a bushel of apples for 25¢ in 1932, that’s about 125 apples, or 1/5¢ per.

People running out and panic buying won’t exactly help the situation either.

Some businesses made out like fat cats with the ability to raise prices in 2020 and the aftermath.

It’s like they get to do Covid again…without lockdowns and subsidies for people.

And not only are, “tariffs are beneficial to less advanced economies when implemented so as to protect certain industries so they can get to be big and efficient enough to have a hope of competing in world markets.” …. but also, in the case of so called “less advanced economies”, in order to protect the self sufficiency of subsistence provision.

Unlike 1932, there is a coffee shortage in 2025. Combined with the impact of tariffs, real coffee will be a luxury item that only the wealthy can afford.

I don’t want to transgress any site policy here but it seems a basic exercise to consider the source. An “adjunct professor of globalization” at an institution calling itself “Universidad Istituto de Empresa” is unlikely to wander too far afield ideologically. I am taking a wild stab that as an “adjunct professor,” our author lacks tenure. Similarly, I am guessing that protecționiste, dirigistes, socialists, and so on neither aspire to nor receive positions as “professors of globalization.” Much less in a “University Institute of Business.” I cannot pretend to any sophisticated knowledge of economics, trade, finance, etc. But I do know a bit of history and have not come across any postwar historian who thought Smoot-Hawley a good idea. What does seem reasonable to me is that a globalized world lacks redundancy and is therefore fragile and vulnerable and there are places for protectionism to make a safety net of sorts when global supply lines go bonkers. Pharmaceuticals down to stuff as simple as saline and LRS. Food. Fertilizer. For those inclined to military adventurism, maybe all the stuff you need to run a military, ships, planes, etc. And the stuff that goes into them. I also wonder, in my economic ignorance, whether the low costs of global trade and supply chains aren’t artificial due to calling anything inconvenient an externality.

“In a world where value chains are global and innovation depends on transnational cooperation, closing economic borders weakens collective resilience.” Yes, his argument seems to be in a world where we have globalized trade, anything that now decreases globalized trade is bad. Especially for the country that starts the counter-trend. But value chains being global is an artifact of the trade agreements that forged the global system; and there is no necessary reason for innovation to require transnational cooperation, other than mutual recognition of the “intellectual property rights” of the innovators, which is a separate thing from innovation itself. And the just-in-time global production system is the opposite of resilient. Its raison d’etre is efficiency, not resilience. So here we are. Clearly a country which wants to go to war with the country from which it sources critical parts for its weapons systems is just plain stupid. And that’s the problem. Stupid, short-sighted decisions by the corporate leadership, stupid legislation by a corrupt Congress, stupid employment of all-at-once big tariffs without any industrial strategy by the Executive branch. There is probably a step-wise way to unwind and then recalibrate and change some of the less than satisfactory aspects of globalization, but it would have to take at least as long as the process that got us into our current mess. And be done intelligently via negotiations with all stakeholders (including the ones left out of the original globalization decision-making), not via a week long reality TV episode. Good luck with that.

Trade between two economies that have similar cost curves can generate benefits like economies of scale and comparative advantage, as long as the benefits are distributed through things like lower prices, higher wages, or profits that are invested in expanding production. Trade between two economies that have different cost curves, like the US paying labour 20 times more than its competitor and the competitor not having to follow environmental rules, leads to unbalanced trade where capital flows to the low-cost jurisdiction. The end result is a trade deficit in the high-cost country and surpluses in the low-cost one, along with downward pressures on wages and anything like taxes or regulations that add to the cost of production. Historically the higher cost jurisdiction will feel pressure on its currency causing imports to be more expensive and eventually there would be that wonderful, long-run equilibrium. The exception to a currency adjustment is when the high cost jurisdiction has both a reserve currency and a habit of pumping-up the economy with deficit spending. This will lead to the country to eventually having a huge federal debt and an economy with a perennial trade deficit. Sound familiar?

US companies decided to move factories offshore and they used both political parties to assist them. These took the form of tax cuts, free trade, deregulation and a high-dollar policy. People who had been stepped on by deindustrialization supported candidates that told them they were getting scr^wed. Bernie didn’t get through nomination and Trump did so they threw their support behind Trump. His approach is too bombastic and scattered to fix the trade problem, but a lot of people are happy he is trying.

Those people who think Trumps bombast, bumbling, and butchery of other peoples livelihood will make their lives better will soon discover otherwise. Politically, there have been no good choices for years.

the graph cited debunks the authors claims. you will notice that world trade collapsed in 1929, well before smoot-hawley. smoot came along well after the depression began.

the countries that immediately dropped out of free trade and dumped the gold standard like the U.K., did better than the ones who did not, like germany.

america was well on its way to the great depression by 1928,

http://www.huppi.com/kangaroo/Timeline.htm

1928

The construction boom is over.

Farmers’ share of the national income has dropped from 15 to 9 percent since 1920.

Between May 1928 and September 1929, the average prices of stocks will rise 40 percent. Trading will mushroom from 2-3 million shares per day to over 5 million. The boom is largely artificial.

1929

Herbert Hoover becomes President. Hoover is a staunch individualist but not as committed to laissez-faire ideology as Coolidge.

More than half of all Americans are living below a minimum subsistence level.

Annual per-capita income is $750; for farm people, it is only $273.

Backlog of business inventories grows three times larger than the year before. Public consumption markedly down.

Freight carloads and manufacturing fall.

Automobile sales decline by a third in the nine months before the crash.

Construction down $2 billion since 1926.

Recession begins in August, two months before the stock market crash. During this two month period, production will decline at an annual rate of 20 percent, wholesale prices at 7.5 percent, and personal income at 5 percent.

Stock market crash begins October 24. Investors call October 29 “Black Tuesday.” Losses for the month will total $16 billion, an astronomical sum in those days.

Congress passes Agricultural Marketing Act to support farmers until they can get back on their feet.

1930

By February, the Federal Reserve has cut the prime interest rate from 6 to 4 percent. Expands the money supply with a major purchase of U.S. securities. However, for the next year and a half, the Fed will add very little money to the shrinking economy. (At no time will it actually pull money out of the system.) Treasury Secretary Andrew Mellon announces that the Fed will stand by as the market works itself out: “Liquidate labor, liquidate stocks, liquidate real estate… values will be adjusted, and enterprising people will pick up the wreck from less-competent people.” (More)

The Smoot-Hawley Tariff passes on June 17. With imports forming only 6 percent of the GNP, the 40 percent tariffs work out to an effective tax of only 2.4 percent per citizen. Even this is compensated for by the fact that American businesses are no longer investing in Europe, but keeping their money stateside. The consensus of modern economists is that the tariff made only a minor contribution to the Great Depression in the U.S., but a major one in Europe. (More)

The first bank panic occurs later this year; a public run on banks results in a wave of bankruptcies. Bank failures and deposit losses are responsible for the contracting money supply.

Supreme Court rules that the monopoly U.S. Steel does not violate anti-trust laws as long as competition exists, no matter how negligible.

Democrats gain in Congressional elections, but still do not have a majority.

The GNP falls 9.4 percent from the year before. The unemployment rate climbs from 3.2 to 8.7 percent.

————————-

if this time line looks eerily like today, its the results of the same form of crank economics, free trade economics.

smoot was simply self defense.

other wise america would have been flooded with cheap imports, as industrialized countries ravaged by free trade crank economics, would desperately export their unemployment, poverty and deflation onto america.

I am tired of your straw manning and the fact that you come here only to natter about “free trade” in a manner so extreme as to be inaccurate.

The post never said Smoot Hawley caused the collapse in trade. It said it contributed.

I am done with you. GYOFB

Well said. Smoot Hawley was a response to the depression not a cause. We don’t hear much about inequality and the Great Depression, I did a quick search and found this: https://www.history.com/articles/roaring-twenties-labor-great-depression

I just read that currently the top 10% of income earners form almost 50% of US consumption. https://www.wsj.com/economy/consumers/us-economy-strength-rich-spending-2c34a571 They also own 93% of American stocks. https://markets.businessinsider.com/news/stocks/stock-market-ownership-wealthiest-americans-one-percent-record-high-economy-2024-1?op=1 While the bottom 50% hold 1% of stocks. The one change that governments have made compared to the 1920s is that for the past 8 years they have been pumping 6% to 8% of GDP into the economy through deficit spending.