Through its selective lending to struggling economies in Latin America, the IMF is helping Washington, once again, to reassert its strategic influence.

A couple of weeks ago, Argentina’s Milei government signed a $20 billion loan agreement with the IMF to help stall a run on the peso and allow it to keep servicing the $41 billion of debt it already owed the Fund. The deal included an unusually large $12 billion chunk upfront. The Washington-based World Bank and Inter-American Bank threw in additional emergency loans of $12 billion and $10 billion a-piece.

As we reported at the time, the IMF loan was granted despite fierce opposition from senior staff at the Fund. Even before the new loan, Argentina, which represents only 0.6% of global GDP, was already the Fund’s biggest debtor by a country mile — accounting for more than one-third of its entire global lending.

Pressure to Sign on the Dotted Line

Bloomberg has since revealed that half of the IMF’s board of directors was opposed to granting the new loan, presumably out of fear that: a) the loan would be used by the Milei government to fund its electoral campaign in the upcoming mid-term elections, just as the Macri government did in 2018; and b) Argentina would once again fail to meet its debt obligations, leaving the IMF in an even more dangerous place.

However, the board ended up buckling to pressure from the IMF’s President Kristalina Georgieva and the Trump administration, and signed on the dotted line. Days later, Georgieva urged Argentines to “stay the course” in the midterm elections in October, sparking accusations in Argentina of electoral meddling.

Siempre lo hizo, pero nunca el FMI había expuesto tan obscenamente su intención de influir en las elecciones de un país miembro, que además es por lejos su principal deudor. Esto es totalmente inaceptable y lesivo de la soberanía argentina. pic.twitter.com/ZvrkY6ajCJ

— Alejandro Bercovich (@aleberco) April 24, 2025

Georgieva’s words were also seen as confirmation that the $20 billion loan was indeed intended to help the Milei government reach October with the economy more or less intact, so that it could “stay the course”. Hours later, Georgieva had to qualify her words, insisting that she was not telling Argentines who they should vote for in the elections but rather emphasising the need for a continuation of economic policy.

Hours later, the photo below went viral showing Georgieva wearing a chainsaw brooch, in homage to Milei’s famous campaign prop. The man to her right, who gave her the accessory, is Federico Sturzenegger, Argentina’s minister of deregulation and government transformation. Sturzenegger, a graduate of the WEF’s Young Global Leader program and former central banker, apparently inspired Elon Musk’s Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE) and was recently appointed to the IMF’s Advisory Council on Entrepreneurship and Growth.

Kristalina Georgieva, la nueva dueña del país, posando con su empleado del mes, el arrastradísimo lamebotas Federico Sturzenegger. Argentina colonia: Macri trajo al FMI en 2018; Massa y el peronismo lo mantuvo en 2022; Milei solo lleva las cosas hasta el final. pic.twitter.com/qrPEkJxc6A

— eduardo castilla (@castillaeduardo) April 24, 2025

A Risky Relationship

However, Washington’s cosying up to Milei’s Argentina is not without its dangers. As the Bloomberg article notes, the more money the Fund throws at the serial defaulter, the more risks it heaps onto its own balance sheet:

There are risks for the lender in handing over so much cash upfront in a program that’s essentially refinancing large existing debts, according to Brad Setser, a former senior official at the US Treasury.

“The Fund would be raising its exposure when the peso is clearly overvalued and the country is repaying bonds,” he said. “It looks like the Fund is positioning itself as, de facto, the junior creditor.”

However, Argentina still has some valuable assets that have no doubt been pledged as collateral. They include its vast deposits of both lithium and unconventional oil and gas.

But this is as much about politics and geopolitics as it is about finance and economics. As we reported a couple of weeks ago, the fact that Milei was visited by the US Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent just three days after the IMF deal was signed speaks volumes about Argentina’s growing importance to the US’ geostrategic ambitions.

On the one hand, it is on the doorstep of the Antarctic, with its vast stores of unexplored and unexploited resources, including the largest freshwater reserve on the planet. It also shares the “Triple Frontier” with Brazil and Paraguay, a key border in South America in terms of population, movement of people and international relations, making it an enticing prospect for a Trump administration looking to reassert US influence throughout the Americas.

The same goes for Argentina’s proximity to the Drake Passage, a wide waterway connecting the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans between Cape Horn (the southernmost point of South America) and the South Shetland Islands off Antarctica. If the US could control both the Drake Passage and the Panama Canal, it would control the two bi-oceanic passages on the American continent.

US Southern Command Pays a Visit

On Tuesday, the new chief of US Southern Command, Admiral Alvin Holsey, paid Buenos Aires a quick visit to discuss issues of “regional security” with Milei and his Minister of Defence, Luis Petri.

El Presidente Javier Milei recibió en Casa Rosada al Comandante del Comando Sur de los Estados Unidos, Almirante Alvin Holsey, junto a su comitiva. Participó también de la reunión el Ministro de Defensa, Luis Petri. pic.twitter.com/bgio4Rx1Up

— Oficina del Presidente (@OPRArgentina) April 29, 2025

On Wednesday, Holsey and his entourage went to Ushuaia, the capital of Tierra de Fuego, to inspect in situ the joint US-Argentine naval base and logistics hub being developed on the shores of the Beagle Channel, a privileged access route to the South Atlantic. The project was initially proposed by the former Alberto Fernández government as a joint Chinese-Argentine initiative, paid for with Chinese funds, until the US got wind of the plans.

#SOUTHCOM Commander Adm. Alvin Holsey & @EmbajadaEEUUarg Charge d’Affaires Abigail L. Dressel traveled to southernmost Argentina today & engaged with @Armada_Arg’s Southern Naval Area Command leaders in Ushuaia to get a firsthand look at the critical role they play in… pic.twitter.com/1ZIOalvS5j

— U.S. Southern Command (@Southcom) April 30, 2025

When Milei took over in December 2023, he switched Chinese participation with the US’. In April 2024, he travelled the 1,860 miles separating Buenos Aires from Ushuaia to meet with the then-US Southern Command Chief, Laura Richardson, to announce the creation of the joint naval base.

“This is a major logistics centre that will constitute the closest development port to Antarctica and will make our countries the gateway to the white continent,” Milei said at the time.

The late Henry Kissinger once described Latin America as a “dagger pointed at the heart of Antarctica” (nice imagery). He also said the following, of course — a lesson Milei is yet to learn:

If Latin America is indeed a dagger, it is growing in value and importance to Washington as the Trump administration seeks to retrench from certain parts of the world back to the American continent as well as assert control over the continent’s two bi-oceanic passages. As El País explains in an article from yesterday, the main goal is to push back against China’s growing presence in Latin America:

Ushuaia is 620 miles from Antarctica. The Chilean base at Punta Arenas is 870 miles away. These are shorter distances than those of other countries in the Southern Hemisphere: South Africa, New Zealand and Australia.

The official purpose of [Admiral Holsey’s] visit was to “supervise firsthand the role of Argentine forces in protecting key maritime routes for global trade,” according to the statement issued by the Southern Command. The Trump administration is also interested in the Ushuaia bi-oceanic passage, in parallel with the pressure it is exerting on Panama to secure control of the Canal. In both cases, Trump’s move seeks to displace Beijing from strategic spaces in Latin America following the Asian power’s advance on the continent in recent years.

Through its lending to struggling economies in Latin America, the IMF is once again helping Washington to reassert its strategic influence in its backyard. It is probably no coincidence that three of the four countries in the region that have outstanding debts with the IMF — Argentina, Ecuador and El Salvador — all have governments that are not only completely aligned with Washington but are also completely on board with Israel’s genocide.

But these countries are currently in a very small minority. Of the four largest economies in Latin America — Brazil, Mexico, Argentina, and Colombia — the only government fully aligned with President Trump is Argentina’s. The others are led by progressive leaders largely critical of the Republican leader’s policies and broadly determined to set their own course on domestic and foreign policy.

Dark Memories

Both the current governments of Brazil and Mexico are determined never to have to use the IMF’s lending services again. Dark memories of the structural adjustments of bygone years remain fresh. During the Washington consensus years of the 1980s and 1990s, both countries went through multiple IMF interventions following currency and debt crises.

In Mexico’s Tequila Crisis (1994-5), a crisis concerning the Mexican peso led to a “bank run,” threatening the stability of Mexico’s private banking sector. The IMF, Bank for International Settlements and the Clinton Administration, clearly panicked by the potential contagion risk, quickly assembled a huge package of funds, ostensibly to bail out the Mexican financial system. However, as I wrote in my 2013 article for WOLF STREET, “The Tequila Crisis: The Prelude to Europe’s Economic Storm”, the real beneficiaries were Wall Street banks and investors:

The fact that Clinton’s then Treasury Secretary Robert Rubin was also a former co-chairman of Goldman Sachs, the vampire squid of recent lore, which just so happened to have aggressively carved out a niche for itself in emerging markets, especially Mexico, is obviously mere coincidence.

According to a 1995 edition of Multinational Monitor, Mexico was “first and foremost among Goldman Sachs’ emerging market clients since Rubin personally lobbied former Mexican President Carlos Salinas de Gortari to allow Goldman to handle the privatization of Teléfonos de México. Rubin got Goldman the contract to handle this $2.3 billion global public offering in 1990. Goldman then handled what was Mexico’s largest initial public stock offering, that of the massive private television company Grupo Televisa.”

But it wasn’t just the US government that seemed determined to lend a helping hand to Mexico’s banks and, indirectly, their all-important creditors. The IMF also extended a package worth over 17 billion dollars – three and a half times bigger than its largest ever loan to date. The Bank of International Settlements (BIS) – the central bankers’ central bank – also got in on the act, chipping in an additional 10 billion dollars.

With such vast sums flowing in and out of Mexico, one can’t help but wonder where the money went and who ended up having to pay for it. In answer to the first question, Lawrence Kudlow, economics editor of the conservative National Review magazine, asserted in sworn testimony to congress that the beneficiaries were neither the Mexican peso nor the Mexican economy:

“It is a bailout of U.S. banks, brokerage firms, pension funds and insurance companies who own short-term Mexican debt, including roughly $16 billion of dollar-denominated tesobonos and about $2.5 billion of peso-denominated Treasury bills (cetes).”

Between 1995 and 2001, the IMF would intervene in multiple debt crises around the world, from Russia to South Korea, to Thailand, Brazil and, last but by no means least, Argentina. This period marks the peak influence of the IMF and, not coincidentally, neoliberalism as a whole. As an article last year in the Monthly Review documents, the IMF bailouts were followed by “a strong redistribution of income in favor of large national and international capital groups that would not have been possible without the deliberate intervention of the IMF”:

[After the Fund’s bailout of Argentina in 2001 and the savage austerity policies imposed on the country, new] progressive governments were elected [in Latin America that were] strongly critical of the neoliberal doctrine, the role played by the IMF, and the withdrawal of the state from providing public health, education, social services, and housing.

Another key element in the relationship between Latin American countries and the IMF occurred in 2006 when Brazil and Argentina, in an organized manner, decided to prepay the debts they had with the international organization.18 This was especially significant, both in terms of the amount involved (for instance, for Argentina it represented 34 percent of the country’s reserves), but also for ending the IMF’s long interference in domestic policy through the imposition of all kinds of conditions. The words of then-President Kirchner announcing the debt cancellation reflected this reality: “This debt has been a constant vehicle for interference because it is subject to periodic reviews and has been a source of demands and more demands, which are contradictory and opposed to the objective of sustainable growth. Moreover, denatured as it is in its purposes, the International Monetary Fund has acted, regarding our country, as a promoter and vehicle of policies that caused poverty and pain for the Argentine people, hand in hand with governments that were proclaimed exemplary students of permanent adjustment.”19

The discredit of the IMF due to the impact of the economic policies it promoted was so extensive and profound in the region that the central (North Atlantic) countries initiated a process of “rebranding” the IMF. Thus, certain “organic” intellectuals began to posit the existence of a new IMF, one that had learned from its mistakes and had modified and rectified some technical errors. As a result, discussions arose regarding the existence of this reimagined IMF, which proposed the emergence of a “new” and “revised” Washington Consensus. However, in practice, no substantive changes occurred in the organization, and its recommendations continued to align with a mainstream view of the economy, supporting financial capital.

Fast-forward back to today, countries in Latin America, like most areas of the so-called “Global South”, are once again facing the looming spectre of currency and debt crises. And as Yves noted in her preamble to yesterday’s cross-posted article, “Global South and Multilateral Financial Institutions: Where Does BRICS Stand?“, the BRICS have failed to create an alternative financial institution that could realistically compete with the IMF as a multilateral lender of last resort.

Washington is clearly aware of this fact. On April 23, Scott Bessent said the Trump administration, “far from stepping back, […] seeks to expand U.S. leadership in international institutions like the IMF and World Bank.” As an article in Africa Watch cited by Yves explains, it’s not hard to see why:

[T]here are very few, if at all any, multilateral institutions that have delivered a “return on investment” for the US like the Fund and the Bank. This is why Bessent yesterday reaffirmed his country’s commitment to the two institutions.

Unlike other multilateral organizations, the US, on its own, has effective veto power when it comes to the most consequential decisions of the World Bank and the IMF. No other country has this power. And in no other multilateral setting does the US have this singular power. Not even in the UN’s Security Council where the US has to contend with the veto powers of the other four permanent members.

Clearly aware of this fact, Washington is once again looking to use the Fund as a weapon to further not only its economic interests in Latin America but also its geopolitical goals. The irony is that Trump’s global trade war, by weakening international trade precisely at a time when countries are grappling with currency and debt crises, makes it even more likely that countries will need the IMF’s assistance.

But that support should not be taken for granted, Bessent recently said:

“Argentina deserves the IMF’s support because the country is making real progress toward meeting financial benchmarks. But not every country is so deserving. The IMF must hold countries accountable for implementing economic reforms. And sometimes, the IMF needs to say ‘no’.”

Presumably, one of the financial benchmarks of which Bessent speaks in relation to Argentina is the cancellation of Argentina’s currency swap with China, with the long-term goal of gradually eroding and perhaps even supplanting Chinese influence in the country. In recent weeks, several Trump administration officials, including Bessent himself, have criticised the currency swap.

One of the countries that appears to have failed to meet the IMF’s new lending criteria is Colombia, whose left-leaning but weak Gustavo Petro government was one of the first in the region to clash with the Trump administration’s policies on deportations. It has also been highly critical of Israel’s genocide in Gaza and has officially applied to join the BRICS’ (largely ineffectual) New Development Bank. Earlier this week, the Fund announced the temporary suspension of a credit line for Colombia that has been in place since 2009.

Prime Target: Mexico

The biggest target, I believe, is Mexico, whose left-of-centre MORENA government has consistently pursued policies aimed at redistributing income, achieving greater energy and food security and, as much as possible, foreign policy independence from Washington.

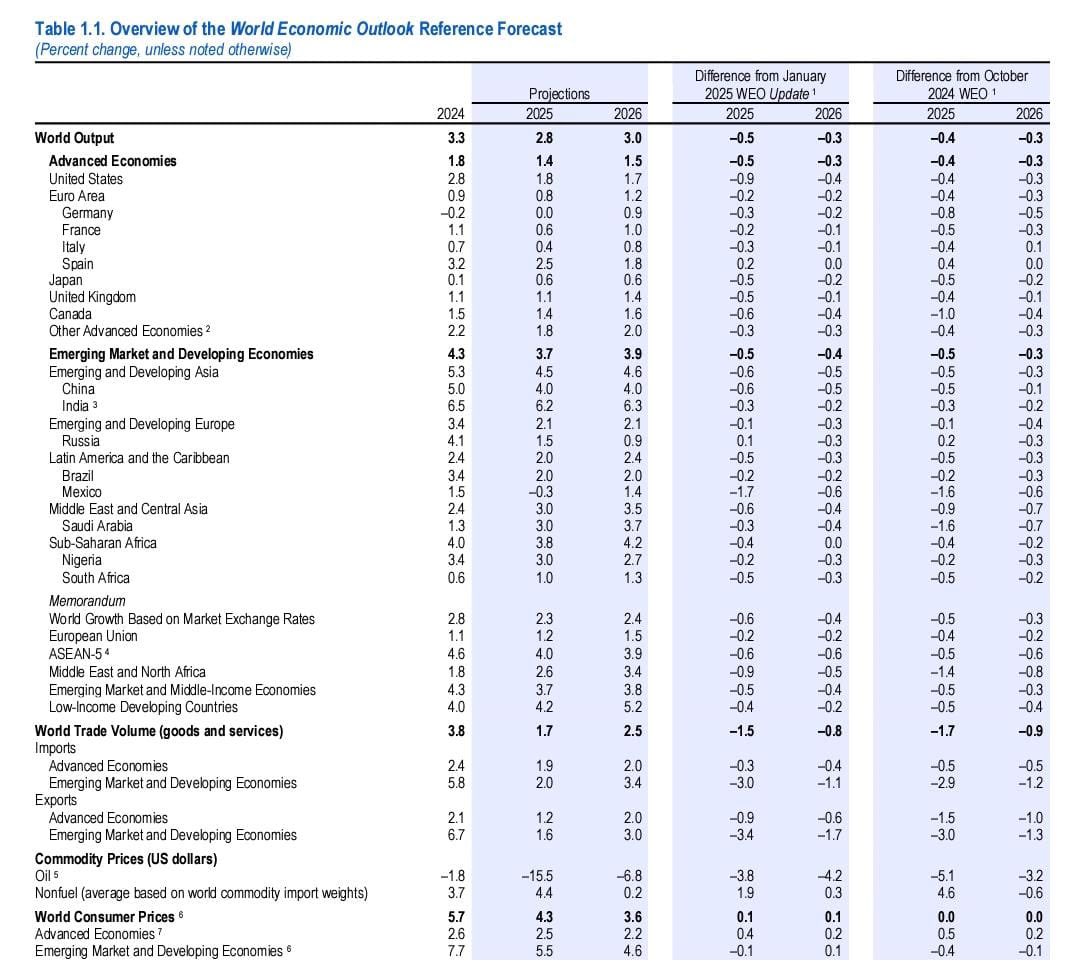

When the IMF released its latest round of economic growth forecasts, something glaring stood out: the Fund had predicted that only one major economy would enter recession this year despite the clear evidence that Trump’s tariff tantrums were already shoving a big stick in the global economy’s spokes. That country was Mexico, whose economy the Fund expects to contract by 0.3% in 2025. As you can see in the table below, it was the largest growth forecast cut of all the major world economies.

The Fund predicts “weaker-than-expected activity in late 2024 and early 2025, as well as the impact of U.S.-imposed tariffs, associated uncertainty and geopolitical tensions, and a tightening of financing conditions,” in part due to the large fiscal deficit AMLO left behind in his final year.

Given that a staggering 83% of Mexico’s exports go to the US, which in turn account for just over a quarter of Mexico’s GDP (26%), it is perhaps unsurprising that the Fund forecast negative growth for Mexico this year. What is surprising is that it expects no other large economy to suffer a similar fate this year.

Even Germany, a country that is already suffering its worst bout of economic stagnation since the Second World War after cutting itself off from its largest energy provider and whose export model is almost certain to be impacted by Trump’s tariffs, is expected to experience zero, as opposed to negative, growth.

The IMF’s forecast and warnings elicited an angry response from Mexico’s President Claudia Sheinbaum.

“That is their vision, they have not understood that in Mexico the Fourth Transformation has arrived and corruption and privileges have ended,” Sheinbaum told the left-wing news magazine Proceso. “The resources of the people are back with the people.”

Sheinbaum was speaking from the Yucatan Peninsula, where she inaugurated the Mayan freight train. It’s worth noting that it was in the aftermath of the Tequila Crisis and the resulting IMF bailout that then-President Ernesto Zedillo, who would later go on to hold senior positions at the World Bank, privatised Mexico’s train network, which essentially put an end to passenger train travel in the country — until the election of Andrés Manuel López Obrador in 2018.

🧵Yesterday, at the annual ceremony commemorating the Mexican Revolution, AMLO announced the signing of an executive order to return passenger train service to 7 routes in Mexico, covering some 17,484 km. (10,864 miles).pic.twitter.com/vF4AN4mBd9

— Kurt Hackbarth 🌹 (@KurtHackbarth) November 21, 2023

🇲🇽🚄 These are the train lines that Claudia Sheinbaum will construct by 2030.

Following the ~1,500 km built by AMLO, Sheinbaum is aiming to surpass 3,000 km of new tracks.

Mexico City will connect to Texas and Arizona, as well as to most major cities inside Mexico. pic.twitter.com/mwuCvquDWc

— Samuel 🇲🇽 (@resisres) October 7, 2024

Zedillo has tried to reassert himself into Mexican politics by lambasting AMLO’s flagship infrastructure projects, including the Mayan train railroad, and accusing AMLO and Sheinbaum of turning Mexico into an authoritarian police state with their judicial reforms. Day later, audio tapes surfaced purportedly linking Zedillo’s wife to the Colima drug cartel (h/t Gregorio).

So far, Mexico’s economy has narrowly averted a technical recession (two successive quarters of negative growth). In the final quarter of 2024, the economy shrank by 0.6% on a quarter-by-quarter basis and was expected to fall into recession in the first quarter of 2025. But instead it clocked up quarterly growth of 0.2% and year-on-year growth of 0.6%. The US economy, by contrast, contracted 0.3% quarter on quarter — from a prior 2.4% rate in Q4-2024.

So far, the Mexican peso has also withstood the vagaries of Trump 2.0’s economic policy surprising well, and is actually somewhat stronger than it was when Trump returned to the White House on Jan 20. The country also currently boasts the highest level of foreign currency reserves it has ever had on record ($235 billion).

In a statement a few weeks ago, Sheinbaum insisted that Mexico’s economy is “doing very well” from a fiscal perspective while also (somewhat ominously) recalling that the country has a $50 billion credit line with the IMF, if ever, ahem, needed. She did, however, criticise the structural conditions imposed by the IMF and World Bank in past bailouts, in particular their demands for sharp cuts to public spending on health and education and the privatisation of state-owned industries. That, she said, will not happen during her government.

If we were to need a loan from the Fund, we would never accept those conditions, because it would be renouncing what we are.

In the table in this essay, how can the 1, 3 and 4th largest economies on PPP basis in the world be classified as ’emerging and developing’?

That’s a part of weaponising the IMF.

The classifications have nothing to do with size. They are generalised categories developed by Morgan Stanley and Moodys back in the 1980s for the purpose of comparing different national markets for international investors, mostly relating to the liquidity of the domestic equity markets and the openness to foreign investors. The IMF and other organisations use them to distinguish different markets because raw GNP figures give an inaccurate comparison between countries with very different types of markets and/or stages of development. PPP adjustments can, if anything, be even more misleading.

I can think of no better advice to give to a country in an economic crisis than inviting in a team from the IMF to report what they see and their recommendations. And after they have boarded the flight back to DC, to take that report and do the exact opposite. Cut pensions? Increase them instead to encourage consumer spending. Don’t let the Chinese in? Ring the Chinese Embassy and ask them what they can do in the way of infrastructure. Sell off infrastructure like water, transport and electricity? Get local corporations to help keep them going on the grounds that if they get privatized, then they are going to have to pay their workers more as the costs of those will no longer be government subsidized. And the surprising thing as that the lower rungs of the IMF probably would agree to these ideas but those at the top of the IMF have agendas instead. And helping countries is not one of them.

I couldn’t help but notice that after the neoliberal U.S errand boy, Ernesto Zedillio recently attempted to reassert himself into Mexican politics criticizing Morenas’s judicial reform, audio tapes surfaced linking him to drug cartels.

https://www.elimparcial.com/mexico/2025/05/01/filtran-audios-de-la-familia-de-ernesto-zedillo-con-presuntos-narcotraficantes/

Thanks for the reminder, Gregorio. Have added a couple of extra sentences and a little hat-tip your way.

Meanwhile we have to endure no end of warnings about Chinese “debt diplomacy.”

Every accusation a confession …

After the Asian Financial Crisis, many Finance Ministries adopted the slogan:

“A Billion a Day Keeps the IMF Away.”

The whole experience of being subjugated by the IMF was so repellent that these countries were determined to never have it happen again. What solution did they come up with? A permanent Trade Surplus.

By running a Trade Surplus, medium-sized countries do not need to apply to the IMF for a bail-out. Problem solved.

Of course, if everybody gets alienated from the IMF and decides that they must have a Trade Surplus because it is a National Sovereignty Imperative, then somebody has to be the big Trade Deficit country. (That seems to be the USA, in today’s world.)

It is all connected.