Yves here. Even though this is a case study, Cape Town’s drought, which came perilously close to having municipal tap water run dry, illustrates what seems like to happen when climate stresses become acute. The short version is the rich took steps that helped themselves but not others, leaving the community in key ways less able to cope.

By Alexander Abajian, Cassandra Cole, Kelsey Jack, Kyle Meng, and Martine Visser Originally published at VoxEU

A growing number of urban areas around the world face water scarcity. Focusing on the prolonged drought that Cape Town experienced from 2015 to 2018, this column examines how adaptation shaped outcomes for the city’s residents and for its municipal water utility. While policy measures including higher prices and usage restrictions saved the city from running out of water, they reduced demand more among wealthy households who were able to substitute away from municipal water, undermining the utility’s ability to cross-subsidise lower-income households’ consumption. Post-drought tariff reforms led to a more efficient pricing scheme that maintained support for low-income households.

Climate change is no longer a distant threat – it is shaping economies across the world. As a result, responses to climate change are increasingly shifting towards adaptive measures to dampen its immediate impacts (Kala et al. 2023). An increased focus on adaptation raises two challenges for policymakers (Carleton et al. 2025). First, how can public adaptation policy be better designed to account for its effects on private actors’ own adaptation decisions? Second, given inequities in access to adaptation across people and communities, what are the implications of climate-driven shocks for inequality and how are these shaped by both existing and new policies?

A protracted water crisis in Cape Town, South Africa provides a striking example of both of these challenges. From 2015 to 2018, the city experienced a prolonged drought that brought the city perilously close to ‘Day Zero’ – the moment when municipal water supplies would fall below a critical level and residential water service would be cut off (Booysen et al. 2019). In a recent paper (Abajian et al. 2025), we examine how adaptation – both before and after the drought – shaped outcomes for Cape Town’s residents and for its municipal water utility. While policy was successful in reducing demand and Day Zero was avoided, we show this policy response to the drought also induced dramatic adaptation among wealthy households, including drilling groundwater wells and substituting away from municipal water. In addition to destabilising the financial viability of the utility, this reduction in demand from better-off households undermined the utility’s ability to cross-subsidise lower-income households’ consumption. The municipal government ultimately responded by reforming tariffs after the drought towards a more efficient pricing scheme that maintained support for low-income households.

The Day Zero experience is both an optimistic story about the efficacy of adaptation as well as a cautionary one about private responses to climate change and the public provision of climate-sensitive goods and services. Similar to the public provision of roads, schools, or electricity, the availability of private substitutes can have important impacts on financing and the distribution of costs across users. A growing number of urban areas face water scarcity, including Mexico City and Beijing (Werner et al. 2013), making these issues front and centre for climate adaptation policy.

Day Zero: The Drought in Cape Town

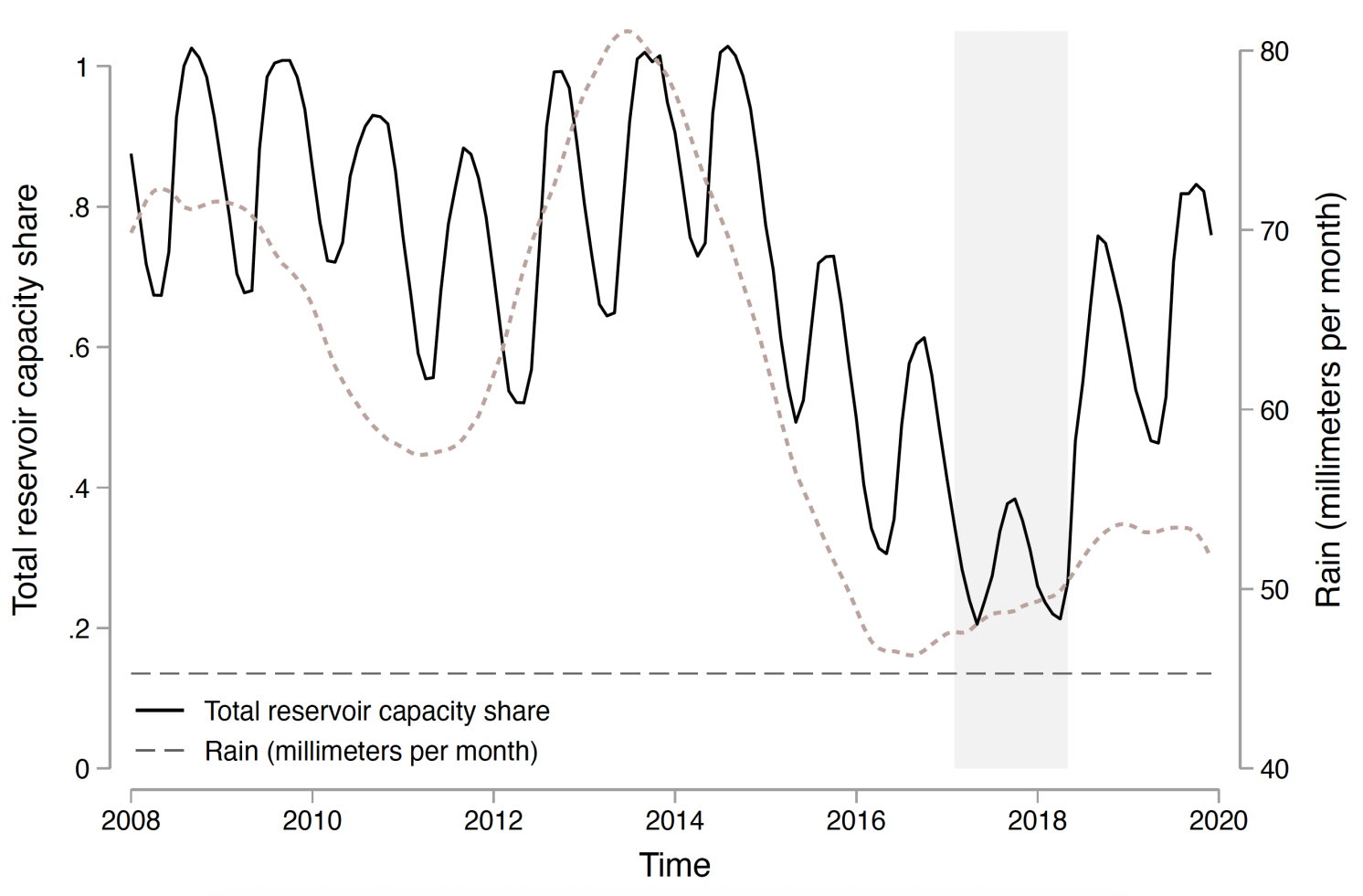

Cape Town is the second largest city in South Africa, and relies heavily on natural rainfall as a source of municipal water supply (City of Cape Town 2020). The city uses an increasing block tariff (IBT) pricing model for municipal water to cross-subsidise the consumption of low-income households. The IBT allows these consumers to pay subsidised rates while charging high consumers above marginal cost to cover the subsidies. However, as shown in Figure 1, a multi-year drought beginning around 2015 began to render existing consumption patterns unsustainable. During the drought (the shaded region in Figure 1), the city’s reservoirs were depleted to near the critical level associated with Day Zero (the horizontal dashed line at 13.5 percent). Starting in 2017, the municipality began to take unprecedented measures to reduce consumption, including steep price increases, usage restrictions, and public information campaigns.

Figure 1 Reservoir levels declined sharply during the drought, leading the city to take emergency measures

Dodging Day Zero

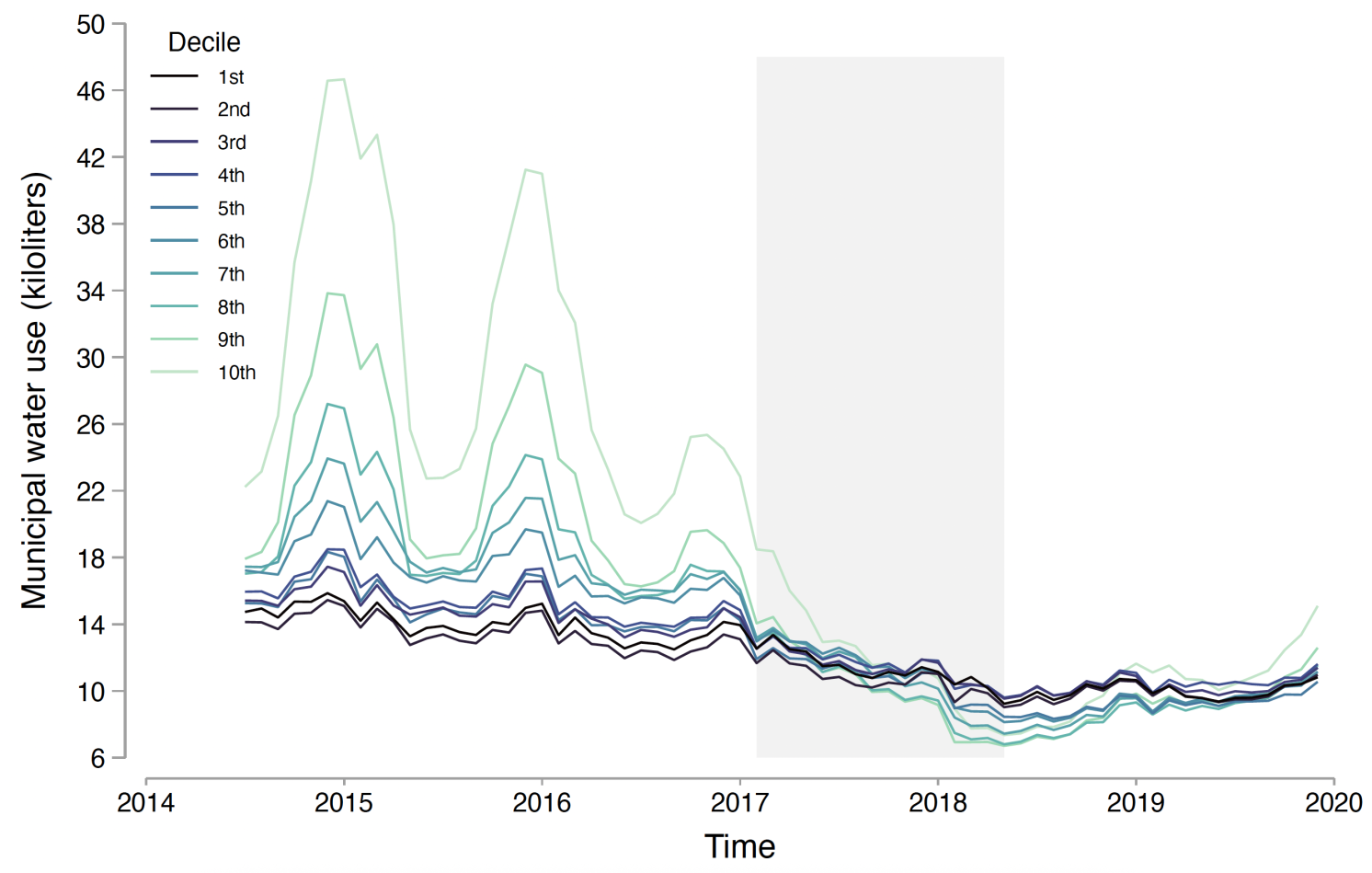

The policy measures – conservation campaigns, higher prices, and usage restrictions – ultimately saved the city from Day Zero. Aggregate residential usage declined by about 50% from pre-crisis levels (Booysen et al. 2019, Brühl and Visser 2021). However, these reductions were highly uneven across the household wealth distribution (proxied by property value in our paper). Wealthier households consumed twice as much water as lower-income households before the crisis (Cook et al. 2021) and saw the steepest declines (Figure 2).

Figure 2 Average municipal water use by household income decile (proxied by home value) before, during, and after the crisis

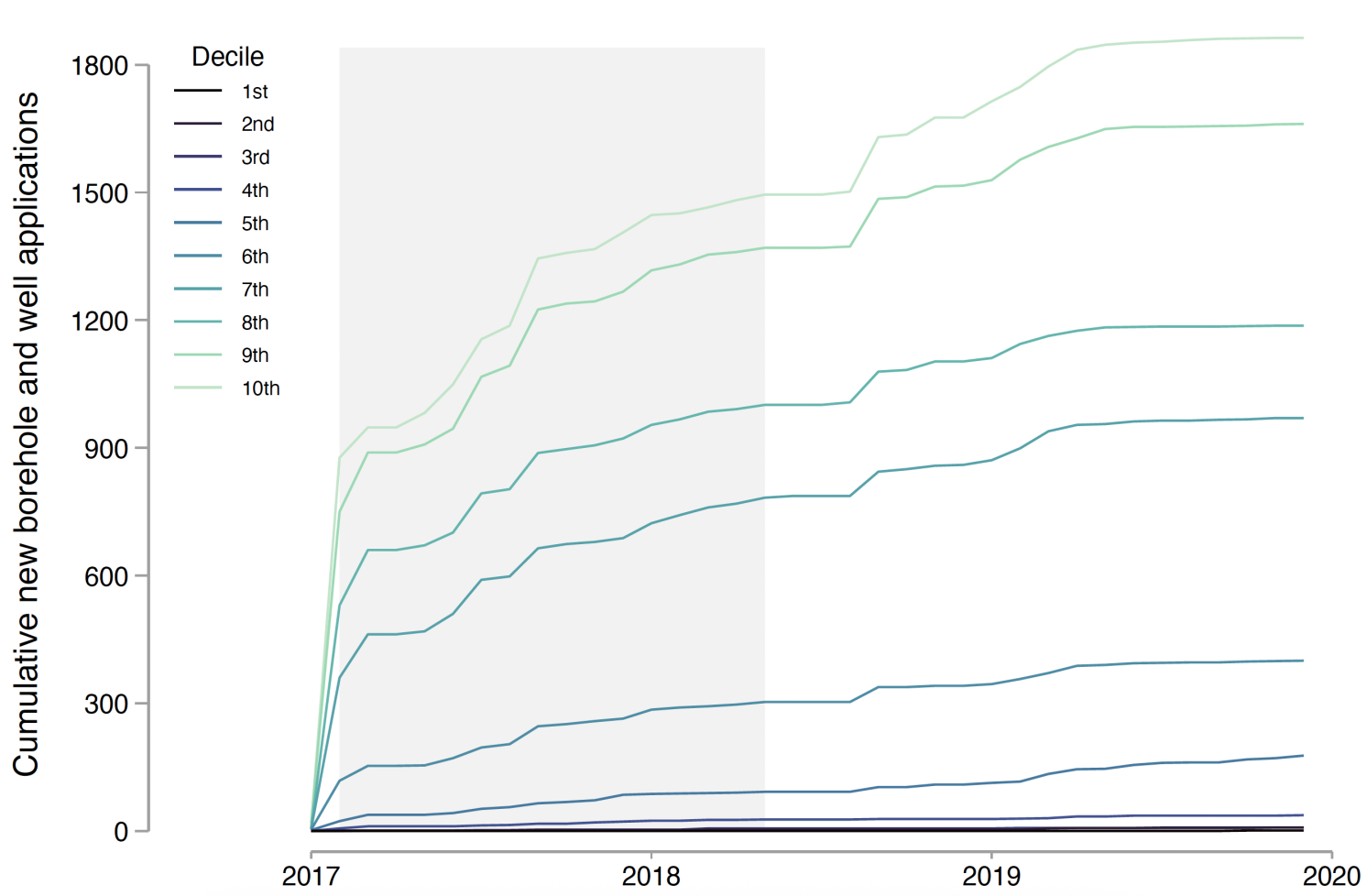

While this was in part a story of behaviour change (Booysen et al. 2018, Bruhl et al. 2020, Brick et al. 2023) resulting from conservation campaigns, public pressure and the price sensitivity of demand, we show that disparate access to private adaptation likely played a critical role. Many affluent households substituted towards private groundwater by drilling wells or boreholes. Figure 3 shows the number of drilling licenses over time; underreporting means that the actual number is likely to be much greater. The ability of wealthy households to substitute away from public water contributed to the steep decline in their consumption shown in Figure 2, and led to them actually consuming less publicly provided water than poor households at the peak of the crisis. Private adaptation had broad implications: it eroded the revenue base of the municipal utility and shifted supply costs onto those unable to afford private alternatives. The cost shift induced by private adaptation meant that the overall share of the cost of water supply borne by the lowest-income households was actually higher than the wealthiest households at the peak of the crisis.

Figure 3 Groundwater drilling applications surged among wealthier households during the crisis

Note: The figure shows the cumulative count of groundwater projects that were registered with the municipality and likely undercounts the actual number by a factor of ten.

At the same time, the city’s water tariff structure, previously reliant on high-volume users to cross-subsidise lower-income households, became unsustainable. To overcome the revenue shortage due to wealthy households’ substitution towards groundwater, the utility introduced a fixed charge component to the water tariff. Total (including both fixed and volumetric) charges increased by around 4% over pre-drought levels in the wake of the drought after fixed charges were added. Fixed charges were also targeted by connection size, meant to proxy for wealth, which offset some of the regressive cost shift caused by wealthier households’ substitution towards groundwater. To further address distributional concerns, low-income households also received a larger allocation of free water each month. Without these policy changes, the distribution of costs would have been highly regressive post-drought.

While policy changes induced by the shock ultimately moved the municipality onto a more efficient pricing regime, changes in consumption patterns across wealth deciles persisted up until the start of the COVID-19 pandemic (when our analysis ends). Wealthier households that had invested in groundwater wells likely continued to rely on them, keeping their demand for municipal water lower than before the crises. This highlights a critical issue in climate adaptation: without carefully designed policies, private adaptation can have persistent effects that exacerbate inequality and threaten the financial viability of essential public services.

Utility Policy in the Face of Climate Change

Our study shows how several features of Cape Town’s experience may help guide utility policy in other climate-sensitive settings. First, the crisis demonstrated the vulnerability of volumetric pricing models to decreases in demand (Borenstein 2022), which will be necessary as scarcity increases. In Cape Town, this was addressed by introducing fixed charges to the tariff structure. While this is an encouraging sign of the potential for crises to induce policy innovation (van der Straten and van der Ploeg 2024), not all policy responses will be as well-informed as those in Cape Town. Second, Cape Town’s experience highlights the efficacy of targeted subsidies for vulnerable populations. During and after the crisis, Cape Town adjusted its water subsidies for low-income households, ensuring they received a free allocation that met requirements stipulated under existing law (Muller, 2008). These households still faced standard price schedules at consumption levels beyond the amount necessary for basic needs, encouraging conservation while ensuring equity.

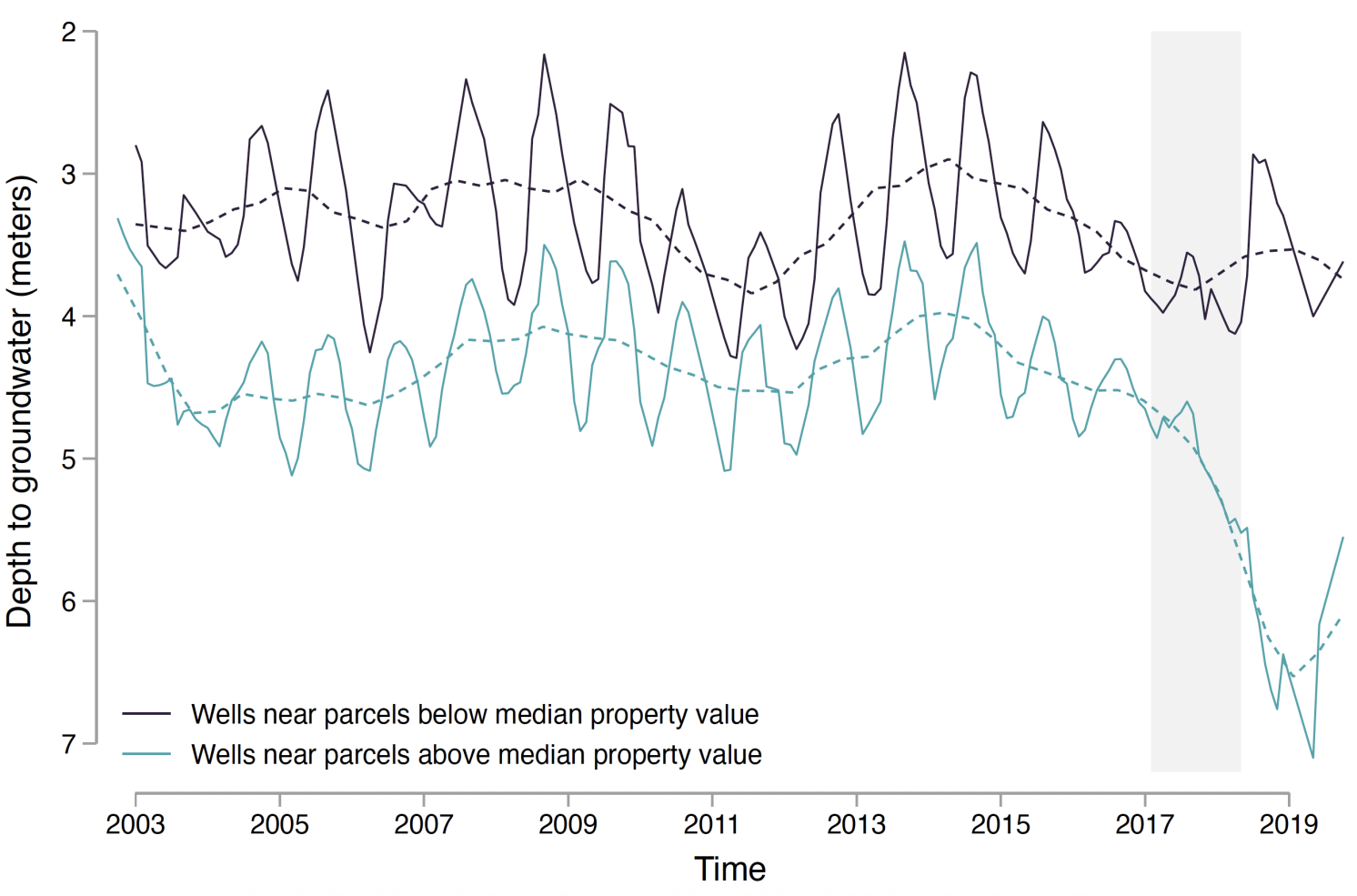

Finally, by studying both the policy response to drought and household responses to policy, our analysis of Cape Town’s experience underscores the interplay between public and private adaptation. An increased dependence on private groundwater extraction raises broader concerns about the long-term sustainability of private use of aquifers, as groundwater levels near wealthier neighbourhoods dropped dramatically during the drought (Figure 4). At the same time, the resulting reduction in demand for public water affects utility revenue and creates pecuniary externalities across users. Similar patterns are unfolding with, for example, the adoption of private rooftop solar in response to rising electricity prices and decreased grid reliability (Brehm et al., 2025). Future climate adaptation policies should anticipate behavioural responses as well as how they may differ across income groups.

Figure 4 Groundwater levels fall during the drought near wealthier Cape Town neighbourhoods but not in other neighbourhoods

<

Cape Town’s near-miss with Day Zero provides a cautionary tale for cities facing climate-induced public resource scarcity. While policy adaptation is necessary, it has the potential to deepen inequality or undermine public service provision unless managed carefully. The key takeaway for policymakers is clear: climate adaptation should balance concerns for equity and resilience. Otherwise, the burden of climate shocks will continue to fall disproportionately on those least able to bear them.

See original post for references

<

Cape Town’s near-miss with Day Zero provides a cautionary tale for cities facing climate-induced public resource scarcity. While policy adaptation is necessary, it has the potential to deepen inequality or undermine public service provision unless managed carefully. The key takeaway for policymakers is clear: climate adaptation should balance concerns for equity and resilience. Otherwise, the burden of climate shocks will continue to fall disproportionately on those least able to bear them.

See original post for references

Reduction in usage only goes so far. At somepoint you need more water than you have due to lack of rain, migration causing more demand and the list goes on.

The fix is hardware. In this case it could be long distance pipelines draining some other aquifer or river moving the problem. Or it could be desalination of sea water and or brackish subsurface water.

You just can’t live without water.

Municipalities in California (drought-exposed) implement several programs to reduce consumption of potable water: low-flow devices, drought tolerant landscaping, drip-irrigation, and water re-use (tertiary treatment at sewage plants and re-use through a separate delivery system) irrigating public grounds. There is also a program of shaming and fines for wasteful practices.

In California most municipalities don’t allow tapping groundwater with a well.

One would think that the “geniuses” in the ANC would have been all over this and taking care of business years ago. Have they? Of course not! Those corrupt idiots are all about lining their pockets and leaving everyone else high and DRY.

The majority party in Cape Town has been the DA for years. Of course, they are now in an alliance nationally with their fellow-neoliberals in the ANC, so it’s six of one, half a dozen of the other.

There is a lot to be said about this. I spent a fair amount of time in Cape Town during the drought crisis and one of my friends is an environmental manager in the city.

Basically, Cape Town’s drought was not so much a drought as a crisis of overconsumption. The citys financial strategy is based on attracting rich people through massive, uncontrolled upper-class property development, without spending anything on infrastructure. Eventually this led to water shortages.

The principal response, apart from shaming people and denouncing the african and coloured townships which actually use far less water than the ruling class, was to pursue the most expensive and/or environmentally destructive practices available. Thus the city invested hugely in desalination plants, despite the fact that the country was facing an electricity crisis artificially promoted to encourage privatization of the national power system. The problem with these plants was that apart from being expensive they were inadequate to provide the needed water, and the water they provided was unsanitary because Cape Town has not invested in its sewage system and the seawater surrounding the Cap’e Peninsula is massively contaminated with bacteria. Eventually the plants were abandoned after vast amounts had been given to the corporate providers.

Apart from this the authorities decided on an extremely expensive deep-drilling programme into the local aquifer. This was slightly less destructive than the private boreholes, which were sucking water up from the Cape Flats aquifer which is also contaminated with sewage in many places and, because the aquifer is open to the sea along the coast, liable to contaminate the aquifer with salt if much pumping were done. However, the water drawn up from the deeps (intended to be pumped into a mountain reservoir) turned out to be non-potable because of large mineral content, and this costly programme was also eventually abandoned.

It does seem that Cape Town’s problem was generated by its subservience to corporate interests and that the solution to the problem was to give money to corporations regardless of the merits of any project.

So the private boreholes sucked up sewage contaminated water? Did the private boreholers prepare for this with their own private borehole water disinfection or did they drink their sewagey water all unknowing?