Yves here. We’ve repeatedly argued that one of the reason immigration has gotten a bad name, particularly officially-sponsored refugee initiatives such as Germany and other EU members accepting large numbers of Syrians in 2015 and 2016, is the lack of planning (including basics like temporary housing) and little to no thought about how to get them employed and otherwise integrated into their new home countries. Keep in mind that nations like Germany accept the proposition that they need migrants to compensate for below-level birthrates. And Syrians in particular were seen as a potentially desirable group due to the high caliber of public education in Syria.

This article looks at some of the nuts and bolts of facilitating refugee integration. Contrary to the common practice of giving new entrants language and job training before trying to place them in jobs, it seems the better way is to get the refugees into work settings and provide instruction in parallel. This makes sense; if you’ve ever tried learning a language, a lot of daily exposure (even if you can’t yet grasp much of what is said), speeds becoming competent. A second advantage of putting refugees with an employer is that they will acquire industry-specific vocabulary early. And making personal connections is a big plus in getting settled in a strange country.

An important factoid is in the headline: this approach is not expensive.

By Giovanni Abbiati, Associate Professor of Sociology University Of Brescia; Erich Battistin, Faculty Associate at the Maryland Population Research Center and Professor of Economics University Of Maryland; Paola Monti, Research Coordinator Ing. Rodolfo Debenedetti Foundation; and Paolo Pinotti, Dean of the Faculty, Professor of Economics at the Department of Social and Political Sciences, and Endowed Chair in the Economic Analysis of Crime Bocconi University; Coordinator Ing. Rodolfo Debenedetti Foundation. Originally published at VoxEU

The number of people fleeing war and persecution worldwide has nearly tripled since the early 2010s, challenging European policymakers to ensure swift integration of asylum seekers into the labour market. This column assesses a pilot programme in Italy that provides early, personalised labour market support to asylum seekers. Even in resource-constrained settings, the early targeted support led to a 30% net increase in employment, improved the quality of employment, boosted language proficiency, and fostered greater social integration with the local communities.

As European policymakers revisit migration policy amidst rising political pressure and renewed arrivals across the Mediterranean, one of the most pressing questions is how to ensure that asylum seekers can integrate swiftly into the labour market. The challenge is not new, but it has become urgent. Since the early 2010s, the number of people fleeing war and persecution worldwide nearly tripled, from 11 million to 36 million. Across Europe, asylum systems are widely seen as too slow, disconnected from economic realities, and poorly equipped to support newcomers’ transition into employment. Finding ways to improve integration for asylum seekers in their new countries can reduce the global tensions around this vulnerable population.

A growing consensus points to early labour market access as a key ingredient for successful integration (e.g. Fasani et al. 2018). Rather than placing asylum seekers in prolonged language or vocational courses before they are allowed to work, fast-tracking them into jobs with targeted support can prevent long periods of inactivity that often erode skills and motivation (Schuettler and Caron 2020). Delays caused by asylum procedures and bureaucratic hurdles to obtaining work permits hinder both economic independence and social inclusion (Fasani et al. 2020). Thus, shortening the ‘waiting period’ and providing employment support services early on can yield significant benefits, for both individuals and host communities.

Despite being one of the EU’s main entry points, Italy has long been an outlier when it comes to timely support. Its asylum system remains fragmented, heavily reliant on emergency accommodations (the so-called CAS centres), and often provides little or no help with job readiness. Asylum seekers are legally permitted to work after 60 days, but few receive meaningful assistance in finding employment. As a result, many spend years in limbo: legally able but practically unable to integrate into the labour market.

It is into this policy vacuum that the FORWORK pilot stepped in (Abbiati et al. 2025). Implemented between 2018 and 2021 in Northern Italy, its core idea is simple: offer early, personalised labour market support to asylum seekers, even before their refugee status is officially recognised.

What sets the FORWORK pilot apart is not just its early intervention model, but its implementation in one of the first-arrival countries, where such initiatives are rare and urgently needed. Most of what we know about refugee integration comes from Northern Europe and focuses on recognised refugees (e.g. Irastorza 2016 and Foged et al. 2022 for reviews of the evidence in Sweden and Denmark, respectively). By contrast, FORWORK tested whether entry-point countries can start building integration capacity from the outset, offering support before refugee status is even granted.

FORWORK offered a concrete model for active labour market policies tailored to refugees’ specific needs – rather than one-size-fits-all educational training or passive support – and was designed to assess if such a model can be timely and effective.

An Early-Integration Experiment

The pilot launched in Italy’s Piedmont region and was born from an ambitious alliance between public institutions, NGOs, and academic researchers. 1 The pilot targeted a critical phase in the asylum process: the period soon after arrival, when most asylum seekers in the country receive little more than food and shelter. It focused on residents of CAS centres, where services are minimal and employment support is virtually nonexistent.

Participants were offered a tailored bundle of services: job mentoring, vocational guidance, language and civic education, and paid internships with local employers. The intervention began with a one-on-one session with a job mentor, who helped assess each asylum seeker’s skills and prior work experience using the EU Skills Profile Tool for Third Country Nationals. Together, mentors and mentees crafted a personalised plan aligned with the participant’s aspirations and occupational background. Mentors remained a steady point of contact, offering guidance, encouragement, and help navigating the Italian labour market.

The programme design allowed for a gold-standard evaluation. CAS centres were randomly assigned to treatment and control groups, making it possible to rigorously measure FORWORK’s impact. A total of 622 asylum seekers were offered participation, and two-thirds (409) accepted. Outcomes were tracked using administrative data, supplemented by two dedicated surveys conducted before and after the intervention.

Benefits: Employment, Language Proficiency, and Trust

In a recent working paper (Abbiati et al. 2025), we show that FORWORK participants were more likely to gain formal employment and stable contracts, and gains were larger for those who participated in subsidised internships. Despite disruptions from COVID-19 during the study period, remote one-on-one mentoring preserved much of the programme’s intended support, suggesting resilience even in other constrained or emergency contexts, not just in ideal conditions.

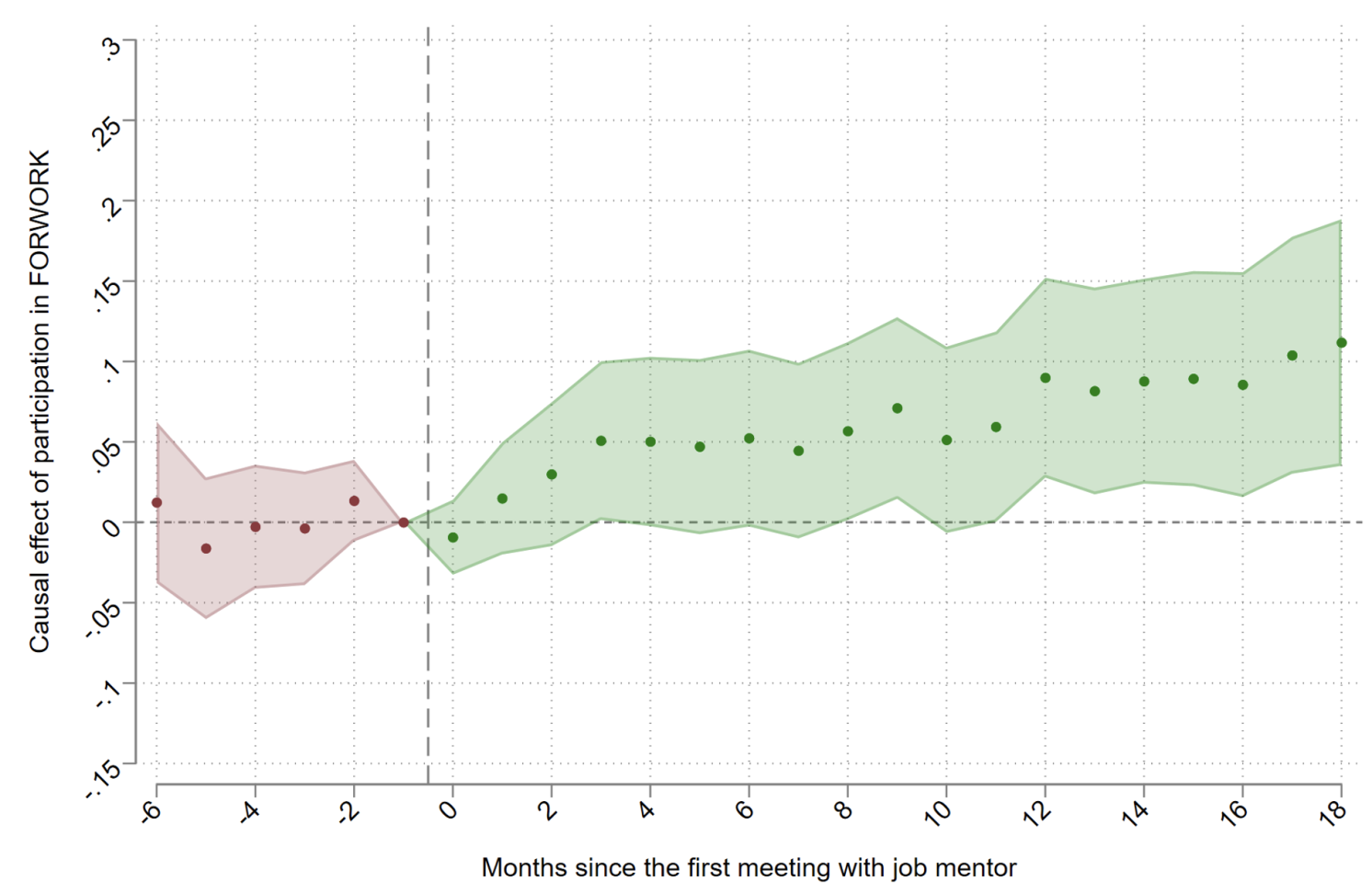

Over an 18-month follow-up period, the pilot led to a 30% net increase in employment. Figure 1 shows that participants’ employment rate was 10 percentage points higher than the control group (43% versus 33%), a striking 30% relative increase. Among men, employment rose by 15 points. Among women, who are typically harder to reach in such labour market interventions, employment rose by 8 to 10 points, nearly doubling their baseline rate. Women, African nationals, and individuals with no prior work experience were especially likely to engage with and benefit from mentoring.

Figure 1 Effects of job mentoring on employment

The quality of employment also improved. Participants were more likely to hold fixed-term or permanent contracts and reported higher monthly earnings (a 30% increase relative to the control group). Paid internships, offered to about 20% of participants, appeared to play a catalytic role, easing the transition from job search to regular employment. Crucially, these gains reflect real increases in employment and not just a shift from informal to formal jobs.In the absence of FORWORK, the data show that over 8% of asylum seekers in the target population would be working under verbal agreements or without contracts, leaving them exposed to exploitation and outside the protections of labour law. This is a striking figure, especially given how little is known about the extent to which newly arrived migrants are absorbed into informal labour markets.

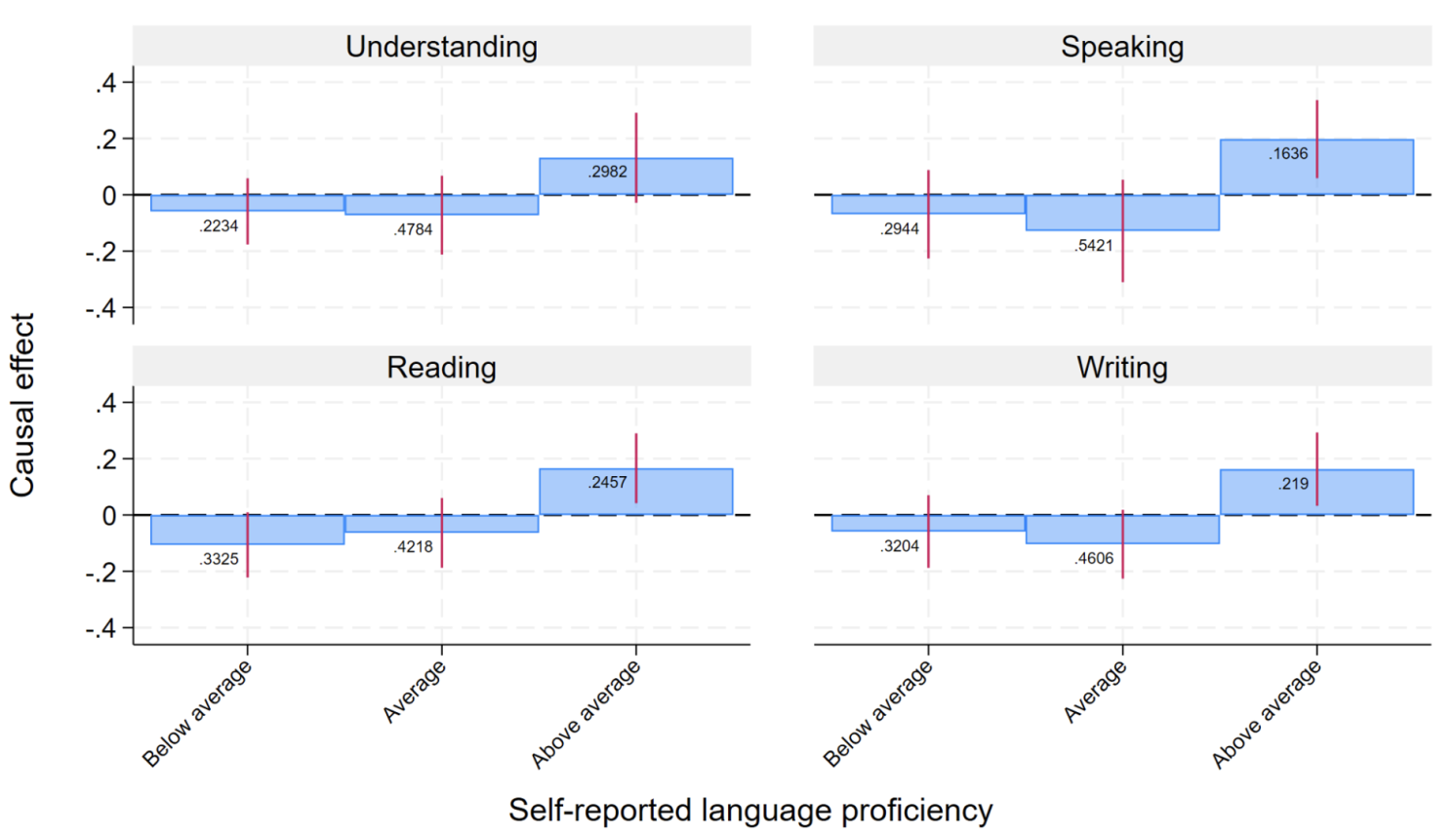

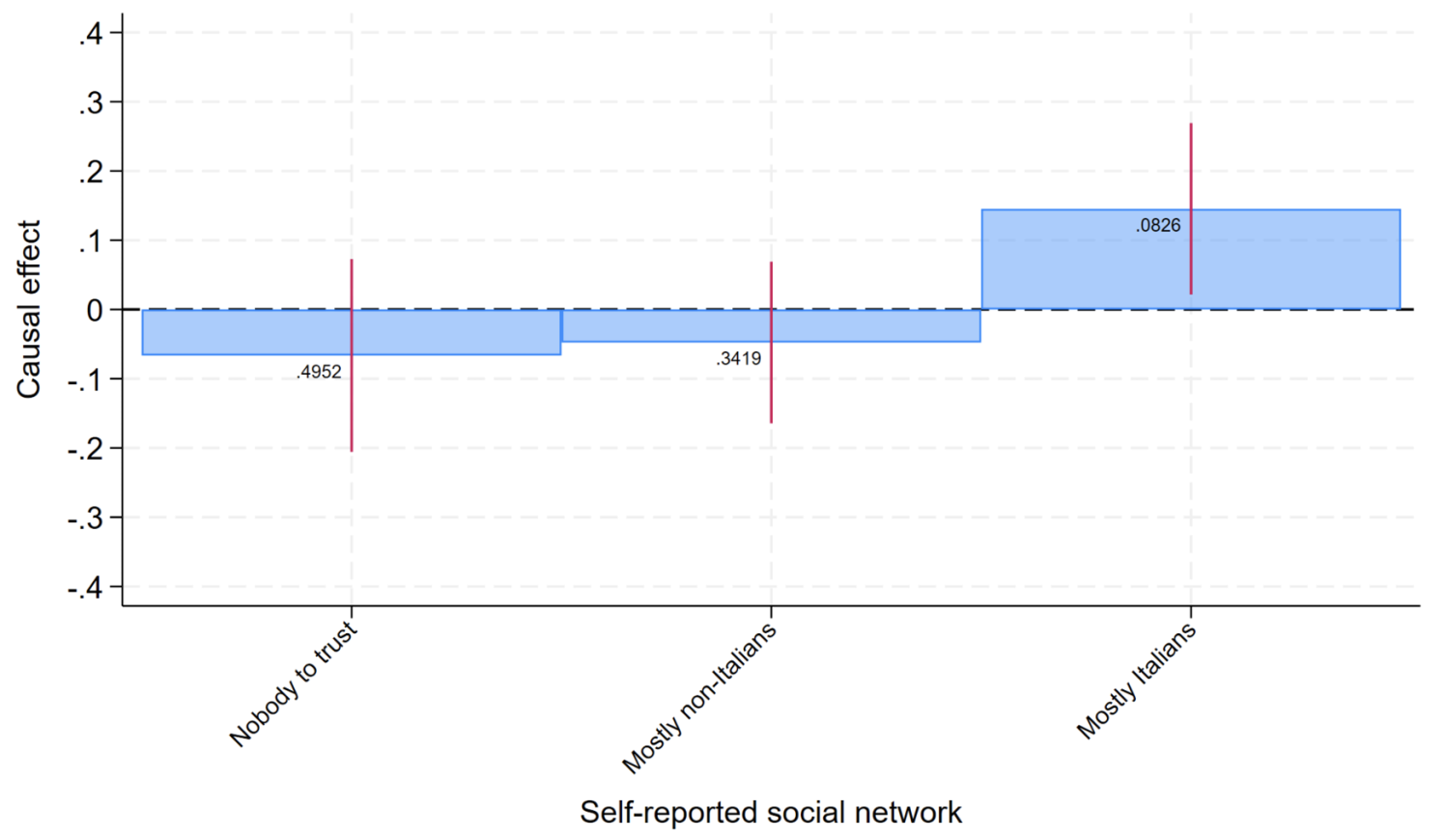

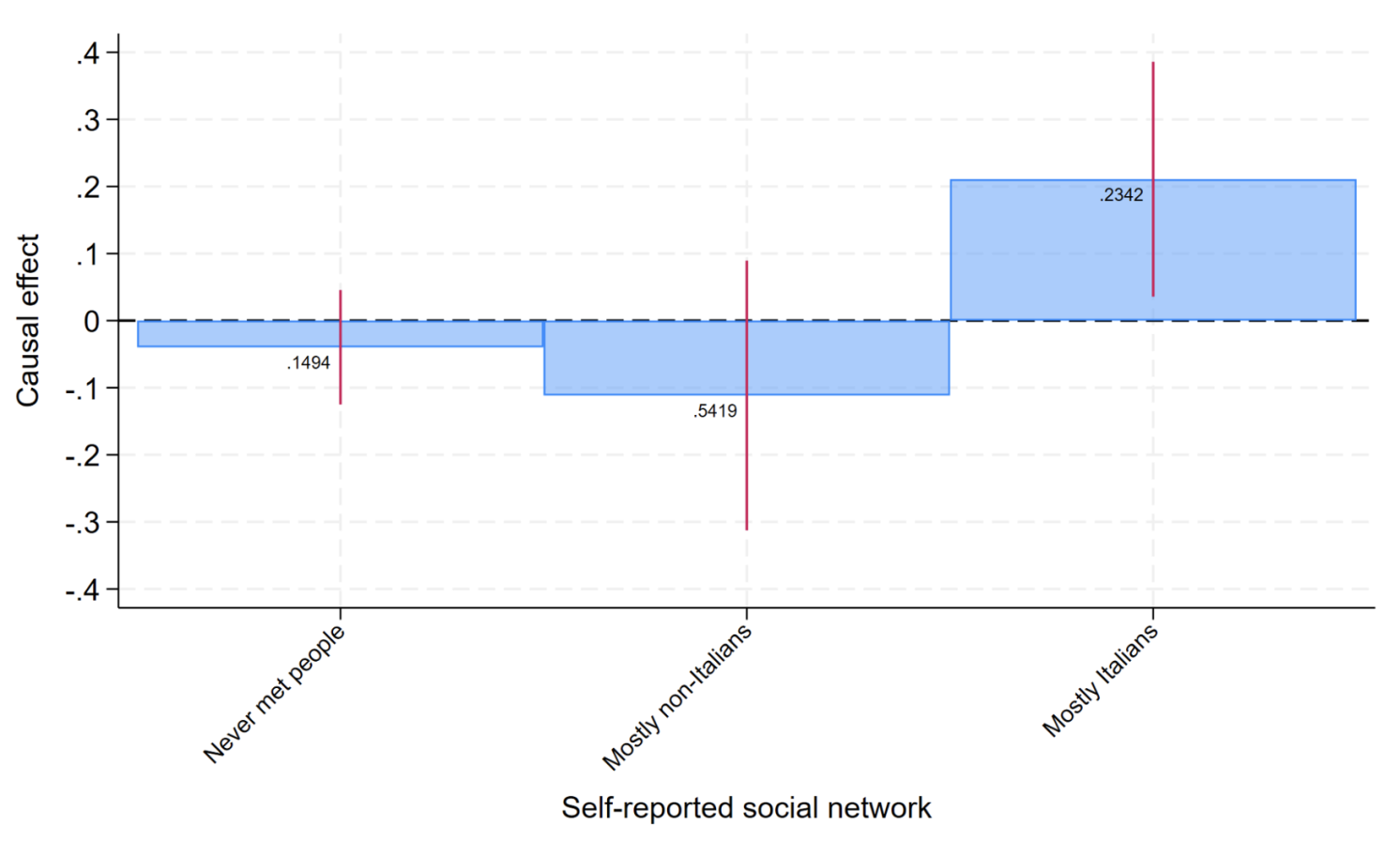

There is more: the benefits of FORWORK extend beyond paychecks. As shown in Figure 2, language proficiency rose by 15 to 20 percentage points across comprehension, reading, and speaking. Participants also reported greater trust in Italians and more frequent social interaction with locals, as demonstrated in Figure 3. These are all signs that early labour market inclusion can also foster broader social integration in the new communities.

Figure 2 Effects of job mentoring on language proficiency

Figure 3 Effects of job mentoring on social integration

A) Trusting people

B) Meeting people

Costs and Scalability

One of FORWORK’s greatest strengths was its cost-effectiveness. The average cost per participant was just over €3,000, a figure in line with standard Italian labour market programmes for unemployed citizens. Nearly 80% of that spending went directly to services and staff, while only 6% covered internships. In other words, FORWORK did not require a new infrastructure or an extraordinary injection of public funds into subsidised employment. It leveraged existing local employment centres and trained job mentors to work with asylum seekers. The model is practical, replicable, and scalable in other countries, provided there is political will and minimal institutional coordination.

What Policymakers Should Know: ‘Early’ Matters

For policymakers looking to reduce the fiscal and social costs of asylum reception, the case for early labour market integration is compelling. The FORWORK pilot stands out as one of the few randomised evaluations of refugee labour market interventions in Europe. While not a silver bullet, it offers a practical, evidence-based model for doing better with modest means. Its core lesson is simple but powerful: early, targeted support can dramatically improve employment outcomes for asylum seekers, even in resource-constrained settings.

This challenges the status quo in many EU countries, where integration services are often delayed until after refugee status is formally granted. But these delays carry real costs: prolonged inactivity erodes skills, dampens motivation, and fosters perceptions of dependency. Worse, it can deprive local economies of much-needed labour, particularly in sectors facing persistent shortages. Delayed integration also raises the risk of informal employment and, in some cases, involvement in criminal activities. These outcomes feed public resentment and fuel political backlash against asylum policies.

We have learnt from FORWORK that these outcomes are not inevitable. With relatively modest investments and thoughtful design, it’s possible to accelerate integration and deliver tangible benefits for both asylum seekers and host communities. Better services don’t necessarily attract more arrivals: they may just improve the prospects of those already present, helping them become self-sufficient sooner. And they may offer a more sustainable alternative to costlier, less effective approaches, such as long-term housing subsidies (Tamin et al. 2025).

See original post for references

This article jumbles Refugees and Economic Migrants together. It fact, it completely ignores any distinction.

The harsh reality is that Third World countries are very poor, and First World countries are relatively rich, which means that a lot of people who were born in a Third World country want to move. I estimate that something like 1 Billion people would move to a First World country next week, if they had the chance.

This article also ignores the lack of a consensus in most countries about the question “What are we going to do about this situation?”

This is an abject misrepresentation. The article is clearly about asylum seekers. The EU attempts to be more rigorous about it than the US:

https://home-affairs.ec.europa.eu/policies/migration-and-asylum/asylum-eu_en

Lets suppress wages then.

I’ve never seen such programs for workers who where forced to emigrate to gain a good salary.

Generally we are not keen about lots of immigration, particularly of unskilled workers, since per your comment, the usual reason is to suppress wages.

However, your reaction is knee jerk. If an economy has a low birthrate, a certain level of immigration is necessary to prevent contraction and a fall in service/social welfare levels (such as not enough people to care for the elderly and young).

Arguing for doing immigration “right” as in having training and getting people into jobs, is not the same as creating a bigger army of the unemployed so as to suppress wages and discipline workers. I trust you are sophisticated enough to see the difference.

Doing immigration “right” would mean adopting the DDR model: no family reunification, repatriation at the end of contact or at the commission of a crime and no renewal of contact until a period of various years.

Of course there should be no access to the social state.

Sorry, do you have a reading comprehension problem? This article is about programs for asylum seekers (I admit that is not in the headline but commenters are required to read the entire piece before piping up, per our site Policies, to which you consented as a condition of commenting). Asylum seekers are allowed in because they are in danger in their home country. Here is a fictionalized example, clearly melodramatic, but it seems you need to see something this blunt, since the concept seems to elude you:

I did not make myself clear, I apologize. I don’t have a problem with reading comprehension, I even read the original in Italian. Refugee and immigrant are a distinction without a difference; in Italy we use these terms as synonyms.

The concept of the “asylum seeker” is ludicrous: the notion that they have a “right” to be in Italy or any other european country because they are “in danger”should be eliminated.

Sorry, the EU has clear rules and procedures for asylum seekers, which is the what the article references. You are trying to pretend these EU legal definitions do not exist. That is what we call here Making Shit Up.

Used as synonyms by normal people.

Since there are 130.000 of these the effects are the same.

I’m not preteding that these defenifitions don’t exist, I’m saying they should not exist and that they should be treated as any other immigrant.

This is grounds-shifting and straw manning of the article and the post. That is bad faith argumentation and a violation of site Policies.

The issues are:

Your views of EU policies are not germane.

I’m arguing for doing immigration right, as you said.

No, you are arguing for doing it right wing.

Gosh mate … you have have yonks of foreign policy to contend with, its neoliberal blow back due to it. Per se the whole GDP argument over costs via the social state is a misnomer due to how where these people come from and why they immigrate to developed nations.

Crying in ones own beer and extenuating it on others is a bad look mate.

My objection is also to the fact that these professors spend there time, energy and taxpayers’ money to help foreigners getting employed while there is a 20% unemplyment rate among the young, while there are low salaries, while in cities like Milan immigrants receive 50% of payments from the social state, while of the more than one hundred thousand “regular” immigrants of the decreto flussi only six thousand found a job and the other “disappeared”.

This is a straw man, as indicated above.

1. The Italian program is for asylum seekers, which the EU treats as legally obligated to receive when they can prove their status.

2. Those lessons can be applied to other countries.

3. Italy’s youth unemployment is due in significant measure to problems with public education. From what I can tell, >20% lack adequate numeracy, writing, and computer skills.

Determining effective ways to integrate asylum seekers into the labour force seems to be a highly economic use of professorial time, and developing and implementing similar comparative programmes to draw young people into employment by providing them with mentors and the opportunity to access soft and hard skills training designed to help them deal effectively with a lifetime of shifting technologies and changing task structures and thereby to make positive contributions to economic and social life seems to me to be a very sensible idea.

In the pre-Thatcher years, local education authorities, local government social services, the various industrial training boards and central government agencies like the Manpower Services Commission did create and execute effective programmes for migrants and young people who had been failed by their schooling and/or their familial or personal situations to help them into employment in those parts of the country with labour shortages even as in other parts of the UK unemployment crept up amongst the over forties. As well as overseas immigration we also experienced internal migration by the better educated young from towns and cities whose industries were in decline to Greater London and Southern England,

Government’s interest in developing empoyment skills first drifted and then skidded and crashed to an end during the 1980s and the UK settled on a policy of doing very little other than increase the prison population, tut-tut at rising drug abuse whilst doing as much as they could to kill our manufacturing industries whilst throwing our North Sea oil and gas revenues into an ever faster flowing river of unemployment and social benefits – along with what Case and Deaton have since termed “deaths of despair”.

I rather like the idea of adapting FORWORK to the current situation in the UK and finding out what traing support systems are most effective at bringing our diverse population into a labour market offering high quality/high wage/high productivity jobs

Interestingly, this integrative approach of newcomers originates from Northern Italy, which seems to have inherited something from the Romans. (Not all imperial legacy is BS after all.)

Labor economist George Borjas has shown that a sudden increase of 10% of the labor force comes with a 3-4% decrease of wages (and a displacement of the local labor force). Borjas suggested an adequate compensation for those suffering from the situation.

That said, refugees must be integrated, one way or another. And this approach seems to minimize suffering for individuals, while being cost-effective. Who could be against that?

And it could be extended to economic migrants with proper planning, so as to avoid popular backlash and demagogic eye-catching operations.