Yves here. I am generally not keen about disagreeing fundamentally with the author of an article, but here I feel compelled to. Thomas Neuburger attempts to find a silver lining in modern society’s pretty much baked in collapse. Perhaps some, even many, readers will take comfort in what Neuburger says below. I find this line of thinking unfathomable.

Neuburger focuses on the supposed advantage of a collapse where a somewhat or very centralized system “collapses” by fragmenting so that lower levels of organization are no longer directed and dominated by the core but instead operate with more autonomy. And in a leap of logic, that is depicted as less oppressive. This is at best a Rousseau-ist assumption, that the state of nature is peaceful.

First, in some genuinely authoritarian societies, the reverse has been the case. Most Iraqis came to lament the ouster of Saddam Hussein. Even though he was brutal, he kept a divided society together and functioning. There was no lower level rebuilding. Iraq is a failed state. Ditto Syria under Assad.

Second, this discussion completely omits what the circumstances of this collapse are likely to be. We will see mass migration due to climate change and more wars over diminishing resources, particularly water and likely agricultural production. The interests that can wield the most force will generally fare less badly as this brutal scramble progresses. The idea that a less hierarchical, less power-driven system will emerge seems remote, at least in the intermediate phases.

The increased primacy of war-making will also increasingly relegate women to secondary status. The greater strength of men will matter again.

Trump is bizarrely accelerating the breakage of production systems which would have become on its own a driver of collapse, if disease and climate change damage didn’t get there first. Just about everything we regard as fundamental to how we live, from the Internet to transportation systems to telecommunications to our power and water systems to medicine depends on highly complex organizations and governments. For instance, our world depends on chips. What happens when their output contracts due to fights over resources? And remember, we have foolishly committed our knowledge to non-durable electronic media (save perhaps optical storage). What happens when our successors can’t readily access it?

Thomas Hobbes deemed life to be nasty, brutish and short in 1651. Future society will be lucky to descend to the level of civilization he knew. Our heirs are likely to shoot past that to an even less advanced state, in terms of application of technologies and tool production and use.

And these societies were not kind to the weak. Sickly babies were often left to die. And that’s before getting to the high toll of childhood diseases. How many of you are confident you would have lived to adulthood in a world with the medical knowledge of say, 1500? Even with our understanding of germs and the importance of cleanliness, how easy will it be to keep that up if municipal water systems are a thing of the past?

Which is all the more reason that it’s so distressing to see our supposed betters accelerating the arrival of bad outcomes with planet-destroying energy hogs like AI and Bitcoin. And I hate to see the supposedly more socially aware cohort going from Green New Deal hopium to collapse hopium.

By Thomas Neuburger. Originally published at God’s Spies

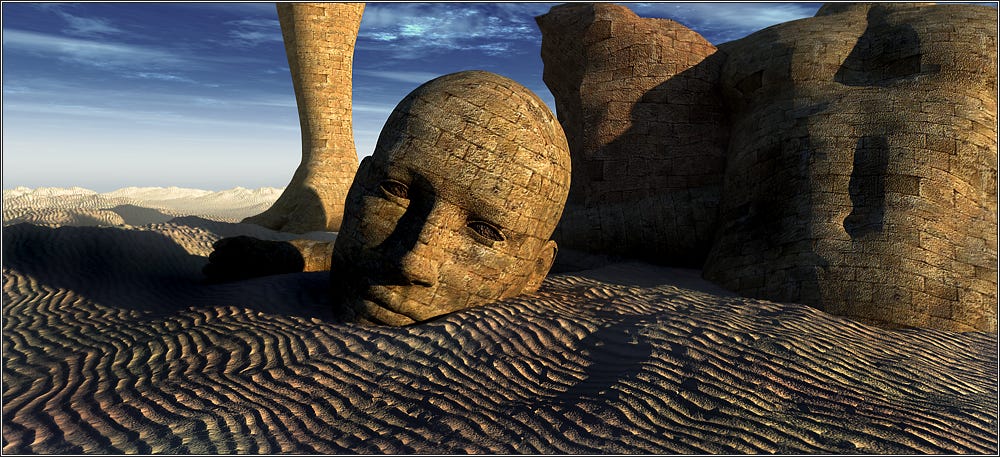

My name is Ozymandias. Miss me yet?

My name is Ozymandias. Miss me yet?

“Those who make peaceful revolution impossible will make violent revolution inevitable.”

—John F. Kennedy

“The state and early civilizations were often seen as attractive magnets, drawing people in by virtue of their luxury, culture, and opportunities. In fact, the early states had to capture and hold much of their population by forms of bondage”

—James C. Scott, Against the Grain

I’ve been writing about how hunter-gatherer and early neolithic lifestyles are both different from the lives most in the West “enjoy” and also are viable alternatives to it. That is, there’s nothing inevitable about kingdoms and empires as a method of organizing society — it’s just what our European ancestors settled into, or were forced into by the ethnic group that overran their lands millennia ago.

For more on that, see here:

Many readers have since asked, “OK, we’re stuck with our rulers — so what do we do? If living controlled in hierarchies is simply a choice made by our ancestors, how do we get out of it now? What is the mechanism of change?”

Valid questions all. I think the answers start with the ideas below.

Three Roads Home

If we think of tribal, hunter-gatherer, or small village life as “home” — after all, as a species we spent almost 95% of our time adapted to smaller, low-hierarchy communities — what’s the machine that breaks these states, these giant engines of control, so we can free our lives?

Keep in mind, those of our species who pathologically love control, will not give it up easily, no more than an emperor would change place with a salt mine slave. Not a normal abnormal emperor at least, not Jamie Dimon, say, or Elon Gates.

This means that control will have to be torn from their grasp. How? I see three ways.

• Electoral decapitation and system restructuring, whereby those in control are removed from power by organized peaceful means and the system rebuilt to be much more fit for the purpose. A transition, in other words, of both leaders and systems from oppressive and predatory engines to egalitarian and nurturing ones.

I’m not sure this option is likely, but this is the “theory of change,” as it’s called, of most sincere, progressive, Party-aligned Democrats, voters and operatives alike. Sanders supporters in his two failed runs were driven by this idea — reform the system using the system’s rules.

• Forceful overthrow and system restructuring, whereby those in control are removed against their will using unapproved means and the system rebuilt. This is the “tell, don’t ask” approach. People in control are told or made to leave, and the place is remodeled when cleared of their debris.

As the Kennedy quote above makes clear, this method often occurs when the first method fails and people have reached their limit. When asking fails, eventually telling takes over, even if it takes a while, years or centuries. All empires fall; all king-controlled states break down; all corrupt big city machines eventually lose power. Often the reason for these failures is forceful revolt — overthrow outside of constitutional means.

Marianne, the symbol of liberty, leading the French to freedom, by Eugene Delacroix (1830)

Marianne, the symbol of liberty, leading the French to freedom, by Eugene Delacroix (1830)

But we can’t say this happens all the time. Yes, all empires fall, but not always from revolt. That brings up the third reason for things to change.

• Collapse, whereby a system fails on its own, brought down by its own inadequacy or felled by an external force. A drought will do kingdoms in. Disease does the same. A meteor shattered the rule of the dinosaurs, collapse on a global scale.

And needless to say, we’re on the verge of it now — collapse of an empire that’s arguably in its last throes, by which I mean the rule of the West over all of the rest of the globe; plus collapse of a climate system that sustains every species adapted to Holocene temperatures.

The Sumerian empire fell for a combination of reasons — population shift and drought being two of them. The Aztec empire was overthrown by Western expansion — the Spanish and Portuguese hunt for global colonies — but the Mayans fell much as the Sumerians did, through drought and social exhaustion. A Greek Dark Age ended the Mycenaeans — the world of Agamemnon and Achilles — just as a Roman Dark Age ended, well, Rome.

Can Collapse Be a Good Thing?

And here’s the rub: we think of collapse as a tragedy. It’s almost built into the name. A “lapse” is a fall from something, often religion (“lapsed Catholic”), and “co-lapse” first meant a group that falls together.

“Falling” is never thought good, and we often think of temples and monuments, ruined and abandoned, romantically, as though a good thing had died.

>The Grand Plaza with the North Acropolis and Temple I (Great Jaguar Temple) at Tikal, Guatemala

We think of the building of large and oppressive social structures as accomplishments, things to desire, and we mourn their passing as though the move away from that life is a loss.

But what if that loss is a gain?

Collapse As Gain

A book we’ll be taking a longer look at shortly is James C. Scott’s Against the Grain: A Deep History of the Earliest States. I first mentioned it here.

One of his theses is that these large and oppressive structures — kingdoms and empires, giant cities and states — were not good, nor were they inevitable in the sense that they represented inescapable social advances. We don’t, in other words, “move forward” to life in large states, nor do we “turn into savages” when those states collapse. That’s a romantic notion, and an illusion.

Here’s Scott on the surprising (to most) four millennia span between the rise of sedentism (small village life) and the oppressions of “civilization” (life ruled by kings).

Note the “We thought … but it turns out” structure of the passage below. There are several of these pairs. From the Preface, all emphasis mine:

The astonishing advances in our understanding over the past decades have served to radically revise or totally reverse what we thought we knew about the first “civilizations” in the Mesopotamian alluvium and elsewhere. We thought(most of us anyway) that the domestication of plants and animals led directly to sedentism and fixed-field agriculture. It turns out that sedentism long preceded evidence of plant and animal domestication and that both sedentism and domestication were in place at least four millennia before anything like agricultural villages appeared. Sedentism and the first appearance of towns were typically seen to be the effect of irrigation and of states. It turns out that both are, instead, usually the product of wetland abundance. We thought that sedentism and cultivation led directly to state formation, yet states pop up only long after fixed-field agriculture appears. Agriculture, it was assumed, was a great step forward in human well-being, nutrition, and leisure. Something like the opposite was initially the case. The state and early civilizations were often seen as attractive magnets, drawing people in by virtue of their luxury, culture, and opportunities. In fact, the early states had to capture and hold much of their population by forms of bondage and were plagued by the epidemics of crowding. Finally, there is a strong case to be made that life outside the state—life as a “barbarian”—may often have been materially easier, freer, and healthier than life at least for nonelites inside civilization.

Each of those pairs deserves its own expansion — the surprising 4,000 year span between the first sedentary villages and plant and animal domestication; the place of wetland abundance, not irrigation, in pre-state sedentary lifestyles; the fact that fixed-field agriculture long preceded kingdom and state formation; and the fact that the agricultural life was not a step up in leisure, but exactly the opposite, a life lived as slaves to the land.

But for now look at the last point — The early states had to capture and hold much of their population by forms of bondage and were plagued by the epidemics of crowding.

There’s nothing romantic or desirable about living in crowds and filth (think Medieval cities and towns). I’ll add without citing for now David Graeber’s similar observation, that many hunter-gatherer tribes who tried fixed-field agriculture abandoned it later, just as the shepherds forced into British industrial hell-towns and factories would have loved to go back, if only their masters had not taken their fields away along with their freedom.

Escaping Civilization

This leads us to think about collapses differently. From Scott’s Chapter 1:

In unreflective use, “collapse” denotes the civilizational tragedy of a great early kingdom being brought low, along with its cultural achievements. We should pause before adopting this usage. Many kingdoms were, in fact, confederations of smaller settlements, and “collapse” might mean no more than that they have, once again, fragmented into their constituent parts, perhaps to reassemble later. In the case of reduced rainfall and crop yields, “collapse” might mean a fairly routine dispersal to deal with periodic climate variation. Even in the case of, say, flight or rebellion against taxes, corvée labor, or conscription, might we not celebrate—or at least not deplore—the destruction of an oppressive social order? Finally, in case it is the so-called barbarians who are at the gate, we should not forget that they often adopt the culture and language of the rulers whom they depose. Civilizations should never be confused with the states that they typically outlast, nor should we unreflectively prefer larger units of political order to smaller units.

Collapse as re-fragmentation. Not death, but rebirth, reconfiguration. The United States un-united, regionally governed. China the same. De-growth and de-globalization. Local control. More choices.

I’ll stop for now, but please consider that thought. Collapses aren’t always terrible tragedies, with fires and armies and death. They’re often just places abandoned because no one wanted to stay. The city collapses, yes, but its people now thrive, living separately, simply and well. No big screen TVs perhaps, but supportive communities replace heartless billionaire kings intent on their own aggrandizement at others’ expense. Fair trade? You’d get to choose.

Of course people will die, especially if the inevitable climate rears its head, but those consequences are, frankly, already baked in. We’ll have them whatever we do. What will come out of that may be a blessing, not “collapse” in the tragic sense, but a wipe of the slate, a chance to construct a much more humane life.

If orderly restructuring fails (it’s failed so far), is “collapse” as considered above worse than violent revolt? I think I might choose the former, however hard, over the kind of great civil war we would otherwise get.

Hopefully degrowth will happen slow enough to be a controlled demolition of the existing system. Not likely with our financial system though. Of course the Russian and Chinese civilisation based nations don’t see it this way and their education systems will stand them in better stead now that Russia has rejected the European based system they were conned into.

What is forgotten is how little time this has taken to become unsustainable, I am in my early seventies and only in the last 30 years has it got out of control, truly an example of the human incapacity to understand the exponential process.

Very true, as Professor Albert Bartlett was known for saying that the greatest failing of the human race is not understanding the exponential function.

As an example, I was looking at a kitchen antiseptic spray that claimed to kill 99.9% of all germs and viruses. Impressive yes? E.coli, a particularly nasty bug, replicates every 20 minutes (the doubling time). Now 99.9% means that out of every 1000 E.coli bacteria, only 1 will survive. It will take just 200 minutes (in ideal conditions with sufficient food, etc – 10 doublings) to get back to 1000. How many of us spray our kitchens every 3 hours or so?

Then I wondered how long it would take 1 E.coli bacterium cell to grow to the weight of the Earth. It worked out as around 44 hours! Forget about 48 weeks later!

What makes you think Russia and china are anymore sustainable? Or there populations are capable of withstanding collapse better?

Russia has enormous ammount of resources, and relatively small population. They can sustain on what they have, longer than anyone else.

Russian population have shown capability of withstanding collapse in the 1990s, when it withstood a collapse. It wasn’t that long ago. People ate potatoes grown by themselves by their dachas. Late industrialization in Eastern Europe meant that lot of people did not lose connection to the countryside. Those that can grow their own food are capable of withstanding collapse better.

Russia has plenty of resources. But it’s political and economic system is no less wasteful. And russia still hasn’t recovered from the damage it suffered population wise during that period. I agree that being more likely to grow some of their own food will help. But it is a matter of degree.

Saying that someone is no less wasteful than USA sounds like a joke. The thing that instanly comes to mind is food waste.

https://www.rts.com/resources/guides/food-waste-america/

The second thing that comes to mind is public transport vs everyone driving a car (a big car, an SUV, a damn truck, all that as a substitute for a small wiener or whatever). There’s also hIgh speed railroad vs airplane, not to mention private jets.

The third thing that comes to mind is appartment building vs everyone having a house. And on top of that, there is centralized heating, and even centralized hot water (meaning no boilers in the appartments). That’s textbook energy efficiency. What USians pejoratively call “commie blocks” is what not-being-wasteful looks like in reality.

Being wasteful is ideological thing in USA, because the alternative is much hated communism/socialism/whatever. It is also closely related to hegemony that USA works so hard to maintain, because the rest of the World is needed in order to pay for the waste. Others can not be “no less wasteful”, because there is not enough stuff for everyone to waste equally.

Another note on Russia that gives its people much more breathing space: she is not exhausted by debt, nor a hereditary nobility or quasi-nobility parasitizing the economy with rent (except for the odd oligarch or two remaining). The ensuing vigor allows Russia to beat the pants off NATO in the Ukraine, for instance. The same is true with China and was the case in Germany postwar.

My personal version of collapse hopium is that it will be quick and complete enough that the rest of the biosphere will have enough diversity left to rebuild itself, as it has after five previous mass die-offs. Inevitably, as Civilization goes down the drain, it will take a lot of the rest of life with it. The two real dangers are that the current climate degeneration will be prolonged long enough to turn Earth into Venus (the Guy McPherson nightmare), or the planetary climate may survive but so much genetic diversity will be lost that only a depauperate biology can survive.

That’s where I’m at as well. It’s all very tragic since it’s really a few hundred ruthless and insane people preventing us from “landing the plane,” but that’s the system we allowed them to build.

Neuburger is yet another Bernie progressive who has reached this position. Jem Bendell, who was once an eager-beaver WEF-er, has come to the same conclusion. Nate Hagens, a Chicago MBA and Wall Streeter, who saw the resource problem first with Peak OIl, has reached this point. There are others, like Daniel Schmachtenberger, who talk of bringing down Moloch before it’s too late. Jason Hickel is an example of someone who still seeks to work within the current institutional framework, perhaps pleading with those in power to relent and land the plane. Kate Raworth works with more enlightened local leadership to try doing the same with local, not Hickel’s global scope.

I wish I could believe that Hickel’s way was a real possibility. I try to cite him here as often as I can to expose people to his ideas, but the hold of “comfort and convenience” and fond if fuzzy memories of some Golden Era are still seductive.

I don’t see how anyone can deny Yves’s depiction of the horrors that await us: warlordism; loss of critical, lifesaving skills and infrastructure; famine. While Neuburger may be sanguine about this drifting away collapse (surprised he didn’t mention the Chaco->Mesa Verde move), others, like Bendell, are not. They see the terrible death and suffering coming. And for him, it’s not that he desires collapse. He just finally reached the point where he had to admit it’s inevitable. Yves’s point:

left me wondering what else there was. Managed degrowth is hopium from a political standpoint. Ecomodernism is technological hopium. When everything is hopium, it’s best to get ready for collapse, isn’t it?

We’ve changed the Earth. Now the Earth is going to change us, our children and our grandchildren. The thing to remember is that what we’re already experiencing with the floods and fires is not Gaia’s wrath unleashed upon us even though that might be deserved. Gaia works to protect life and foster its amazing diversity and complexity. That’s how we arrived at the stable Holocene. But we’ve been so foolish as to sicken our benefactor. We’ve poisoned her with our industry and farming. We’ve overheated her with our Happy Motoring and flights to see our ashram in India. We’ve devoured her forests and plowed her prairies. Now we’re going to experience what living in a damaged biosphere is like as Gaia seeks a new equilibrium, a process that’s likely to be as violent as the planet was in the distant past.

In any case, thanks to Yves for posting this. It’s a view that more and more people are reaching, not because it’s desirable, but because it’s inevitable.

That is an awful article. In the first paragraph alone apparently hunter gatherer lifestyles are viable now. I’d suggest 7 billion people doing that would result in no wild life in about a year.

Followed by the implication that kingdoms and Empires are they fault of Europeans. They came along pretty much everywhere else as well.

Well some of us are a broken record when it comes to the assertion that human behavior is far more a result of biology and practical reality than culture. For example the Noble Savage crowd like to point to Polynesia as some kind of peaceful paradise but the reality was that those island dwellers were constantly fighting each other. As Yves says dividing societies into smaller units will merely result in the same hierarchical setups writ small. Hunter gatherers had to maintain territories and fight with other tribes to keep those territories from being stripped of resources. So the practical reality is that a) biology has us constantly striving to make greater numbers of us and b) only industrial civilization can keep all those new individuals alive. Collapse will inevitably mean depopulation as it always has.

Of course that’s what many of the billionaires want but their fallacy is the notion that they are the ones worth preserving. Our leisure class doesn’t do much other than produce green pieces of paper. They need to get their heads straight about who are the “useless eaters.” At the moment I’d say the top among that last group would be one Donald Trump and his bizarre government.

We share this “hopium”. Unfortunately, I voted for Obama and have a reasonably good memory.

“The planet’s not going way — “WE’RE going away – George Carlin

We have had many periods when the poster board individuals with ” the sky is falling” messages were prevalent. Just as with school shootings, such messages meld into the background for most people as such crises keep reappearing. We do not heed them, especially since we have lives to live on another plane, and solutions are muddled. This reflects our lack of knowledge, lack of depth, and lack of critical thought and timely action during the best of times, when critical thought could help prevent crises. Our society has spawned such ignorance for its own protection from tumult and desire for political stasis in those empowered at the moment. It is sold to us in educational/media driven fantasies. Fantasy has created most of our narrative, and dreams of wealth covered it with icing for comfort. Is it too late to change this script?

Per your point, the Permian–Triassic took hundreds of thousands of years to set in fully:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Permian%E2%80%93Triassic_extinction_event

The current human civilization could collapse much quicker than the animal life of P/T extinction. As you have pointed out, cities/towns rely on municipal water/sanitation services to control communicble disease. These services require massive amounts of electricity to operate. Without abundant electricity the human population will diminish rapidly. (I’m contemplating absconding with a few PV panels to an agricultural hinterland ;).

It sounds like the old “it has to get worse before it gets better” idea, when we actually need to stop actively making things worse.

The middle management martinets such as the uk chance-llor prefers not to believe that beneficial growth requires a healthy specimen to start with.

Placing some faith in death and resurrection doesn’t look a great bet to me.

What we need to do is not what we’re gonna do. My hopium is that governments will learn to dig. The only way a diminished civilization is going to survive is underground. I’m not sure how far, but there is a level where the temperature is pretty constant. I think a couple of billion people are going to die before TPTB realize they can’t survive without servants and start devoting resources to saving the proletariat. Don’t worry about life, or the ecology. You think in too short a time period. In a billion years even the longest-lived nuclear fallout goes away. Heat is not going to kill every cockroach before a couple evolves to survive. The Permian die-off was only about 250 million years ago. The meteor strike that killed 90% of all species was only 65 million years ago. Give it 20 or 30 million years and Gaia will heal herself. Of course human beings aren’t going to be around that long, even if we survive this crisis.

Collapse enables those who are prepared and especially those who nudge the timing, to pick up assets cheaply.

All systems contain their own demise.

Nepotism corrupts, making those, who should manage well, into idiots who invite subversion.

There is also a natural collapse that occurs every 500+ years. We had another Bethlehem Star event in December 2020.

I’m with Yves, freedom isn’t free.

My 4th great-grandfather lived most of his adult life on the wilderness frontier of colonial America. In 1773 he moved from civilized Enfield, CT to the newly settled areas in modern-day New Hampshire along the Connecticut River. In 1800 he moves his family to CNY which at that time was also the frontier.

While he lived to be in his 60’s his life had its fair share of tragedy (and I have dozens of other ancestors who suffered as such)… his first wife died at about the age of 39 during child birth. He lost a 30 year old and 35 year old daughters to child birth as well. He lost at least 5 grandchildren to various childhood illnesses as well.

Most of his family is documented in the probate file of his second oldest son, but in those papers include the realization that such freedom also comes at the cost of staying connected… one sister who is presumed to be living has actually been dead for 5 years; one sister is named but they have forgotten her married name; one deceased brother is recalled but not his name (but he’s listed because he is believed to have had children); another sister is listed but her name too has been forgotten although the name of at least one of her sons was remembered.

Wow, that is intriguing. Thanks.

For full disclosure and added info… the wife and 2 daughters are presumed to have died from childbearing complications. In reality I only know their timing of death relative to when a child was born. It is quite possible they died of something completely unrelated and the timing is coincidental, however absent modern medical capabilities it was not uncommon for women to die during childbirth or acquiring an infection during childbirth that killed her days or a few weeks later.

My original post only infers it, but my 4GGF had a large family and that was normal then because modern birth control didn’t exist. While much of my family is pre-American revolution… I do have some family that arrived later and families were equally as large in England, but my observation was that the death rate was far higher… fewer children made it to adulthood and many adults died by their mid 40’s if not earlier.

Frontier colonial America was probably a lower disease risk environment (for European whites), but the current world has a LONG ways to go before we get to that population density. A civilizational collapse now would, I suspect, quickly pass into a phase that looks like the 14th century plague Europe on steroids!

Interesting.

A few years ago I did some family research based on extensive notes and relationships (and stories) I came across written by a maternal great aunt 70 or 80 years ago. All of my ancestors came from Ireland, most during the famine. Even though she was second generation, names were forgotten, multiple childhood deaths, war, and work deaths were mentioned, and entire descendants, second cousins of hers, lost to memory through lack of communication after moving away to other States (and Australia). And these people were grateful to be living in a safer and better organized society than 19th and early 20th century Ireland.

I know little about the paternal side. Whenever I asked all I was told was that it wasn’t a happy history, just forget it (I traveled to Ireland to look around, all I found on the paternal side – documented through birth records – was a foundation and partial chimney close to the central west coast).

I imagine that collapse would guarantee that the amount of information on family ties and relationsips I dug up over a year would be nearly impossible to find.

Moving is huge and absent even our creaky USPS or the internet you don’t have to move super far by today’s standard.

The sister I mentioned who had been dead for 5 years… She was living on the west side of the Connecticut River in VT when she died (and had been there for decades; She and several of the older siblings didn’t move to NY in 1800 with their father). In today’s world I could drive from Fabius, NY to where she lived in VT (Waterford) in about 6 hours. And yet when her brother died in 1844 they hadn’t shared communications in at least 5 years! AND Roswell was one of the siblings who remained in the VT/NH area until about 1816 when he came to CNY. Of note, he lost his only child and son (one of the deceased grandchildren) to illness or accident at the age of 13.

As for your personal paternal genealogical side… have you considered a DNA test? It won’t tell you who your direct ancestors are and even though Ancestry and the like may suggest who your ancestors are take any and all suggestions with a pound of salt. That said, you may have other, unknown to you, branches of the family who have more complete history that is available to you once you know where they are. If you are interested in doing more on your paternal side and would like some directional help, you can email me at (remove the spaces) arhill 1989 @ gmail .com.

In terms of an imagining of a post apocalyptic world, covering the fall of western civilisation, there is no better SF novel than George R Stewart’s “Earth Abides” from 1949.

It covers both the massive loss of human knowledge and skills, and interactions between survivor groups.

I have no idea whether the TV series matches the book, but I doubt it.

I am much more inclined to look favourably on the anthropological and sociological studies that James C Scott (who defines himself as almost an anarchist) and Karl Polanyi (very much a liberal socialist historian) outlined of non-capitalist societies than those of most political economists.

You might just include them in a grouping that includes Tawney, E.P. Thompson and other left historians, but they are more anthropological in choice of subject matter.

Their background tends to be more empirical research based and not predicated on imaginings of collapse, though they may hold some messages for future non-capitalist survivability, this is not their primary purpose.

Cormac McCarthy’s “The Road” comes to mind.

Thanks I’ll get a copy.

“Earth Abides” covers 2-3 generations, (though we don’t really know how old Ish is at the end), and slow regrowth of a village life, so an interesting timescale. There is also a journey across the apocalypse from California to the Mississippi, though that is a sub plot.

Octavia Butler’s Parable series, written in the 90s, is quite prescient about our current circumstances of California fires and the decline of central authority. She pictures a world where there is an intense, high stakes battle to establish the dominant worldview because the worldview that dominates our thinking now had crashed and burned.

Yes, I read that recently. One thing that must be noted, both Parable and The Road feature a livable climate.

In both the books and our reality, it is a polycrisis. Climate is an aggravating factor now, but it’s only in the early stages.

I don’t think Butler’s interstellar goal has aged well, though. We’re less in need of a goal than a new story.

Good point. Searching for food and evading malice are shared features. The endings are somewhat similar as well. In both cases oasis of sorts is obtained.

I was chatting with DeepSeek recently about this topic area, and it surprised me by pointing out how the terms “polycrisis” and “The Great Simplification” are competing framings – one emphasizing the complexity of the situation we face, and the other the postulated necessity for civilizational contraction.

Eliot Jacobson has reposted at the former twitter a graph with a variety of types of ideology with regard to beliefs about collapse and political orientation.

I read lots of science fiction sixty years ago – Earth Abides among hundreds of others – as a junior high schooler I kept a list. Orestes and Conway’s restoration of global civilization in just a few hundred years in Collapse of Western Civilization – A View from the Future seems too optimistic to me now. But one never knows when something surprising might happen.

I feel that Neuberger’s argument, that a collapse of a society will lead to a better one, does not work for an individual country, but, hesitantly I wonder if it would work on a global scale. That is, a collapse of all countries as they are today. Because, we’ve already seen what happens when a country collapses – other countries basically pluck the failed state of all its worth, and eventually the natives (with or without foreign help) rebuild a fairly identical state (Afghanistan, Iraq, Haiti, Syria, etc.)

But, if a major natural, or man-made, catastrophe were to affect the entire globe, where all the states collapse, there are no armies left, and the human population has been almost decimated, then the remaining humans would be forced to revert to a more “primitive”, sedentary/agricultural way of life. Though, I suspect, eventually, they’ll progress to the same form of rule as exists today.

The main missing point in this argument is a definition of what is a better form of government: democracy, communism, anarchism, Star Trek-like altruism, something else? Without a goal, how could humanity rebuild into something better? Aren’t today’s states emulating/borrowing from ancient greek and roman states, Demokratia 2.0?

The collapse of a state will simply redefine the winners and the losers. So, to me, it doesn’t make sense to argue that a collapse will lead to something better without stating what that “better system” will be. But, if a better system is envisioned, then the question becomes “how do we get from here to there?”.

The coming collapse is not going to be the mere failure of a state apparatus within the more or less normal functioning of the rest of the world.

I was remiss in not reminding readers that it will be like the Jackpot…without William Gibson’s techno hopium. From his novel The Peripheral:

One of my favorite Gibson novels. I wish they hadn’t cancelled the TV series.

The Jackpot does lead to a future where the dominant political economy is kleptocracy and in that way we’re already ahead of the game

“how do we get from here to there?”

With the possible exception of some very isolated communities with a lot of luck, this is not a valid question assuming collapse. If you could on some larger social level plan how to get from here to there then you are not talking about collapse but transition.

But in a collapse scenario, even on the global scale you describe… the armies only disappear in an accounting perspective. All the weapons and trained soldiers just don’t evaporate. Someone will put them to use for their perceived good or advantage and that someone probably does not care about getting “from here to there” or we would already be there or in transition to there.

Just look at history… there are plenty of examples where a strong central authority loses its grip/control and in many if not most cases the outcome is a bunch of smaller warlord states. Even if you fall further down the civilization ladder than that there are an awful lot of weapons and ammunition to be expended before armies disappear that someone thinks they can organize.

Thinking about civilizational collapse in this way, as a third option for social change, after reform and revolution have failed, strikes me as characteristic of a type of intellectual who wants to rule. In current circumstances, the Machiavellianism of The Prince might be more in order for political thinkers who want to influence the current order for the betterment of general social circumstances.

Unfortunately, many intellectuals have not come face to face, in their own lives, with material scarcity, and many are in positions from which they would rarely see systems breakdown, except in the abstract, which effects how they think about the topic. Having lived poor in one of America’s ghettoes during the early years of covid, where supportive systems are technically in place, but in practice, don’t work, there is nothing romantic about social breakdown. I can understand where that type of thinking comes from, I believe, and can sympathize with it, but it’s this kind of gap between expectation and reality in which privilege consists, and its not conducive to accepting facts and working with what you have towards a goal.

There are enough cushions and moats around sufficiently privileged sectors of society to soften many blows. Barring something like total electrical failure or nuclear war, the form our in-progress breakdown may take could be the spreading of the conditions of the ghetto to rest of the society. Unevenly, as one or another sector of the economy is proletarianized or as regions face disaster. I worry for those who have an unrealistic or even romantic picture of social breakdown.

We have to change our material circumstances, collectively. Where we can’t, we’ll adapt by changing our minds. Its understandable, but the one is not a real solution to the other.

The cold hard truth is that we can’t go back. Those much smaller earlier communities had population sizes limited by carrying capacity. There was unused land that people could expand into by cutting down the trees and turning the area into productive farms to feed themselves and a little more to trade for goods but we don’t have that anymore. Remember, in the year 1000 AD there were only about 35 to 55 million people living in Europe. Now? About 745 million. We are way, way above our carrying capacity. On a planetary scale, there are over 8 billion humans alive in the world right now but the carrying capacity of our planet has been reckoned as about only 500,000,000 and it is only complex societies with the ability to trade with countries around the world that enable this massive population to survive. If they collapse, we may be sitting around a campfire singing Kumbaya alright but we would be eating long pig while we did so.

I once contemplated what would happen in a local community meeting after a general collapse and you want to know one of the first things that I thought of that should come up? Opium. No, I’m not a druggie but after a collapse I figure that it would be a good idea to have access to some pain medicines for accidental injuries, women in labour, etc. After all, where are all the needed pharmaceuticals going to come from. You need to take tablets to keep you alive that come from a chemist? Then you are going to be all out of luck after a collapse. A large chunk of the population will go away from just that within a year or two of a general collapse. The media like to point out how it will be the survival of the fittest in such a scenario but that is just Hollywood bs. I will be in real life the survival of the fittest communities. Those able to adapt. But it is going to be hard for all those regional managers and technical consultants to learn that the only place they will have in the new world will be as farm labourers.

Here I am reminded of a chapter from “World War Z” where millions of Americans fled to Canada as they figure Zombies can’t stand the cold. One father, who has never been camping in his life, takes his wife and kid there saying that they have plenty of food in the car and will live off moose burgers and berry pie. Half the food is used just getting there and in one of the camps things slowly fall to pieces as the game is long shot out and resources dwindle. People die by the ten of thousands due to the cold and influenza which ends in unofficial cannibalism. Any comradery is long gone and people painfully realize that most of the stuff that they brought with them is just useless junk. The world that followed was one that resembled more an early 20th century one but there they might have been lucky.

And there ain’t going to be no topless chick to lead us into this new world.

“there ain’t going to be no topless chick to lead us into this new world.”

Except maybe in your opium dreams while the camp “dr” tries to amputate your gangrenous leg.

My rising senior read WWZ his freshman year for Honors lit. His project/story for this book was a description of how to escape the zombies by going to his grandmother’s and aunties ranch because the sisters had gardens, animals and water. He said it was too difficult to get there and native Americans would be suspicious of white people. He also said that it was fun taking the horses and the other animals down the mountain with his grandfather and uncles to the winter camp.

Riding down 7000 feet with all the animals is pretty amazing for a little kid. I picked up the baby half way through but the older one made it down although he had to ride with Grandpa for the really steep part.

Those hoping for a better life post catastrophe should hope for a pretty complete catastrophe that leaves no functioning state standing. Even just one remaining state, even if its no more than a better organized group of thugs, will inevitably grow through graduated or accelerated conquest, the speed of which will be determined by the availability of whatever lethal technologies remain. Remember that the Romans managed to get pretty far without gunpowder. Well organized phalanxes proved quite adequate for the task.

Humans suck. Too much?

Yes. Human exceptionalism in a nutshell.

I think so. Humans in the rich world of the Global North are living in a world that is radically different from the world that selected our species to survive. This world has been constructed over the past century using what’s been learned about our evolutionary “buttons” like dopamine to install, like software, a worldview that has little to do with reality, especially in its elevation of humans, at least powerful and wealthy humans, into gods who imagine their own near omniscience and who seek omnipotence as they busily torture Nature for her secrets.

Humans are capable of refraining from exercising the power of technology over Nature when employing that technology would disturb what Edward Goldsmith, author of The Way: an Ecological Worldview, the vernacular worldview:

Goldsmith goes on to provide many examples of vernacular peoples who still refrain from using modern technologies because they see how they will disrupt the natural order and their own society. While Goldsmith’s examples are drawn from what we Westerners call “primitive,” we see Anabaptists like the Mennonites and Amish who follow the same practices in the midst of our technological society. They eschew insurance not only because, for them. that evinces a lack of faith in their God, but also because calamity for one individual, like a barn burning down, requires the whole community to assemble to rebuild.

While I often criticize the never-ending drive for more stuff and comfort and convenience, it is with the goal of awakening the Bernays-shaped consumer to the madness of their behavior. I don’t consider that Taker behavior (from Quinn’s Ishmael), even though it’s been around at least since agriculture, as an immutable aspect of humanity. Too much money has been spent to shape us into such destructive creatures for it to have been innate.

The late James Hanson and his Dieoff dot org work cured me of such hopium a good while ago. A version of what Neuberger hopes for might possibly occur after a massive die off of 95% or so.

John Michael Greer has devoted a lot of words to this topic, much of it in his now defunct Archdruid Report blog but also now on his Ecosophia site. Much of is summed up in the phrase “Collapse now and avoid the rush” meaning the time to make preparations for surviving a greatly lowered standard of living is now. Think Amfortas attempting his own private autarchy.

Truth to tell people have been talking about this since the industrial and medical revolutions made rapid population increase a thing. One could suggest that socialism–a lot more popular a hundred years ago–was thought of as a way out of inevitable collapse by appealing to the social side of our natures.

So of course capitalism with its love of status and overconsumption is a big part of the problem. Long range people like Trump and the tech bros are anarchists pretending to be libertarians. Greed is not good.

So yes culture and ideas do play a role but how to fight the human tendency to revert to the lowest common denominator? It may take the palpable threat of collapse and as Grier says by then it may be too late.

The biggest population increase has occurred since rather unlimited fiat money took over, there was 2.1 billion of us in 1933, now 90 years later there’s almost 4x as many of us.

I would also recommend another James C. Scott book: Seeing Like A State: How Certain Schemes To Improve The Human Condition Have Failed.

David Hackett Fischer – The Great Wave. Excellent history of previous societal overshoots and subsequent stressful “retrenchments.” Focused on European history since he could access significant documentation for his analysis.

John Gray in Straw Dogs:Thoughts on Humans and Other Animals states: “Epidemiology and microbiology are better guides to our future than any of our hopes and plans.” Sounds about right.

In our corner of southwest New York State, and the adjoining areas in Pennsylvania and Ohio, the many expanding Amish communities might have the best chances of survival. That assumes a slow collapse, not a nuclear holocaust.

They are not totally dependent on infrastructure: electrical, sewage, water. They have no cars or computers. More importantly, they have developed a strong and functional social network over the past 300 years. They have systems in place to provide mutual aid: farming, firewood cutting, help for new mothers, support for elders. And everyone knows how to do stuff and make things. From local sawmills, to growing food, to building houses, to raising animals, to sewing, to cooking, to bow hunting (they can gut and process a deer.) Yeah, their life spans will be shorter and they will have ‘supply chain’ problems; for example, all the glass chimneys for the kerosene lamps are made in china. And, of course, what happens to the kerosene supply? And, lids for canning jars rely on modern industrial and transportation systems: they disappeared during CoVid!

I am cleaning out my father-in-laws large workshop, filled with lathes, drill presses, bandsaws, giant belt sanders, etc. In addition, there are all HIS father’s hand woodworking tools. An Amish friend and his two oldest boys are doing the hard work of moving stuff and, in return, they will be taking the machines and the non-power tools: the clamps, wood planes, drill bits, files ….. and the many many buckets of nails. They are already being distributed among the local Amish community.

Collapse,in and of itself, is neither tragedy nor farce. it has no moral component. it is not a punishment or a reward. nor is there necessarily an exit strategy, or a happy, or even marginally acceptable, end point. the reality is, i think, that all species ultimately reach their expiration date. it is fatuous to insist that unlike all other species,homo sap is immune to the forces of evolutionary extinction.

in the phrase famously coined by larry niven and jerry pournelle:

“just think of it as evolution in action”

I’m with the commenters who see Neuberger as a would-be elite on the outs with the actual elite, fantasizing about their displacement. Revolution and collapse are never gentle.

“Of course people will die…” This mindset is how people continue to turn their backs on the 2014-22 genocide in Donbass, the 2016-present genocide in Myanmar, the 2023-present genocide in Gaza, etc. How is it ever OK for the person doing the dying?

Over half of the 8 billion current lives in being are urban dwellers. We are completely reliant on petroleum and electrical infrastructure for survival. “Collapse” is no water, no food, excrement and garbage rotting all around us, while armed gangs rob and torture at will. No thanks.

What a wonderful conversation. I need to leave and do errands. Thanks ALL!

I just finished reading Greer’s “Decline And Fall”. He covers this topic quite well. A few of the chapters cover localization after collapse and there is little “rah rah” praise. As with present society there may be advantages regarding some areas of society, but serious disadvantages, too, like highly authoritarian local governance.

Think Puritan Society in mid 17th century Massachusetts. Yuck.

It would be foolish to rule out the possibility of a collapse; it strikes me as equally foolish to characterize such an outcome as a positive one.

If it must happen, I certainly don’t want to be around to experience it.

Cue the opening monologue in Mad Max II: The Road Warrior …

“My life fades. The vision dims. All that remains are memories. I remember a time of chaos. Ruined dreams. This wasted land. But most of all, I remember the Road Warrior. The man we called “Max”.

To understand who he was, you have to go back to another time. When the world was powered by the black fuel. And the desert sprouted great cities of pipe and steel. Gone now, swept away. For reasons long forgotten, two mighty warrior tribes went to war and touched off a blaze which engulfed them all. Without fuel, they were nothing. They built a house of straw. The thundering machines sputtered and stopped. Their leaders talked and talked and talked. But nothing could stem the avalanche. Their world crumbled. The cities exploded. A whirlwind of looting, a firestorm of fear. Men began to feed on men.

On the roads it was a white-line nightmare. Only those mobile enough to scavenge, brutal enough to pillage would survive. The gangs took over the highways, ready to wage war for a tank of juice. And in this maelstrom of decay, ordinary men were battered and smashed.“

What an exciting and necessary debate/discussion.

It should always be kept in mind that Rousseau’s Social Contract was formulated in opposition to contemporary absolutism and took the form of an imminent critique of the theories of sovereignty that were then used to legitimate such theories.

Rousseau brilliantly showed that their arguments, in fact, presupposed the existence of the people as a coherent and sovereign political entity. He argues on page 49 of the Social Contract the following:

“A people, says Grotius, can give itself a king. So that according to Grotius, a people is a people before giving itself a king. That very gift is a civil act, it presumes a public deliberation. Hence before examining

the act by which a people elects a king, it would be well to examine the act by which a people is a people. For this act being necessarily prior to the other, is the true foundation of society.”

The people are both prior to and implicitly superior to any and all forms of government. Roussesu argues

that the people thus constitute the “true foundation of society.”

What about Cuba?

What about the entire “Global South”?

In past empire collapses of note, they all happened in a vacuum pretty much, but that was then and this is now.

None of them were connected via money, as it either didn’t exist or some other empire scooped up the largess which was always precious metals, typically minted into other peoples’ money.

When the deal goes down it’s gonna be epic in oh so many ways with every country utilizing the same sort of money, a fiat accompli.

I’m more of a voyeur in regards to such things and find it utterly fascinating living in a time where a global turning point is about to occur, and unleash mayhem.