Yves here. The post below summarizes an important post published by the European Investment Bank, which estimated climate risk for 170 countries. Needless to say, this is a very important exercise and one hopes other experts will seek to refine it. Even using a pdf compressor, the study proper was too large to embed, but you can find it here. We have included the juicy part, the country rankings, at the end of this post. Update: Reader Tim H kindly sent a sufficiently compressed version of the full article, so you can now find that below.

I have not read the report in full but was surprised at some of the findings, per the country ranking. 1 = global average risk, so higher figures are worse.

I find some of the results to be curious:

![]()

I have seen Bangladesh cited, for nearly two decades, as in even in early Pentagon-connected reports about the geopolitical risks of climate-change mass migration due to flooding. That is confirmed in a 2023 paper by the LSE:

Nearly 60% of Bangladesh’s population is exposed to high flood risk, a greater proportion of the population than in any other country in the world other than the Netherlands, and around 45% are exposed to high fluvial flood risk, the highest figure in the world.

Consider also:

![]()

Huh? The UK is not even remotely self-sufficient in food. Frequent flooding and unexpected heat waves have further reduced farm output. We posted that UK dairy farmers are using grain they had planned to use for winter feeding now due to not being able to graze them. From the BBC earlier in the week in Farmers face crisis as drought causes grass to fail:

Dairy farmers are facing a crisis, spending thousands of pounds feeding their cattle grain that should be saved for the winter.

This year’s long, dry spring – the warmest and sunniest on record – has forced many farmers to take unprecedented action.

Sarah Godwin, a dairy farmer in north Wiltshire, has had to take feed out to her cows for the first time in her life. She said she had “never known a season like this, never known the heat, the lack of rain, and for so long”…

“The grass is completely dried up,” Mrs Godwin explained.

“There’s no goodness in it, it’s just completely stalky with no nutritional value at all.”

I have not read the methodology carefully, but a quick search showed no reference to “food” in the main text (there were studies in the references that did include “food security” in their titles, and only one paragraph that had the word “water” in it.

This seems to be the source of the blind spot about the necessity of feeding populations:

To quantify the impact of climate change, we first collect structural information about the economy (e.g., the economic contribution of agriculture, population) and climate-related information (e.g., temperatures, share of the population exposed to sea level rise). We then typically resort to results of empirical studies and the academic literature to transform the data into economic impacts. Finally, adaptation capacity, also expressed in percentage points of GDP, is accounted for. The various physical risk factors are discussed below, the underlying variables are shown in Table 1 and Table 2, and Appendix A.1 contains the methodological details

So the focus seems to be entirely on economic effects, and not broader survival.

That may explain these ratings:

![]()

![]()

But this score makes intuitive sense:

![]()

Uruguay has produced nearly all of its electricity from hydropower (although there is some risk long term of water scarcity). It is not only self-sufficient in food but is a significant exporter given its size. It was very high on my list of possible expat destinations due to being well positioned in light of climate change.

By Matteo Ferrazzi, Senior Economist European Investment Bank, Fotios Kalantzis, Senior Economist European Investment Bank, and Sanne Zwart. Originally published at VoxEU

Climate risk is at ‘code red’ level for the entire of humanity, prompting investors and policymakers to focus not only on the risks but also on the opportunities related to the green transition and on strategies to enhance countries’ resilience to climate change. This column presents new climate risk scores for more than 170 countries, distinguishing between physical and transition risks. The scores reveal that emerging and developing economies are the most exposed to physical risks, mainly due to acute physical events, sea level rise, and high temperatures. Transition risks are more relevant for fossil fuel producers and wealthier countries.

Interest in country-level climate risks has grown in recent years, in particular in the years following the 2015 Paris Agreement, which outlined clear decarbonisation pathways for each nation. Investors are also progressively aware about the long-term risks of climate change. Indeed, the exposure to physical climate risk can have negative implications for, among other things, sovereign debt (Zenios 2022, Bernhofen et al. 2024), the cost of debt and sovereign ratings (Beirne et al. 2021, Standard & Poor’s 2015, Agarwala et al. 2021, Revoltella et al. 2022), fiscal sustainability (Agarwala et al. 2021), and even on political stability (Moody’s 2016, Fitch 2022, Volz et al. 2020). Transition risk, by contrast, is linked to three main factors: policies, shifts in consumer preferences, and technological breakthroughs (Semeniuk et al. 2020). Reputational effects and legal actions due to failure to comply with environmental standards are also relevant.

In practice, three broad approaches are used to assess climate risk at the country level: modelling, scenario analysis, and (index-based) scores. Multidimensional macroeconomic models aim to evaluate the macro impacts of climate change. Some organisations are regularly developing scenario analyses, often based on the output of the models, to sketch multiple plausible and consistent representations of the future (not forecasts) under different policies and circumstances. In general, such scenarios project the possible future outcomes of climate change over the (very) long run (60-80 years from now). In addition to modelling and scenario analysis, index-based scoring help assess climate risk and rank countries (for example, the Notre Dame Global Adaptation Initiative (ND GAIN) and Germanwatch). Ratings agencies have started to develop their own assessments to complement their rating methodologies (Volz et al. 2020, Gratcheva et al. 2020). Typically, they combine environmental, social, and governance (ESG) criteria to support investors in making informed investment decisions.

New Climate Risk Country Scores

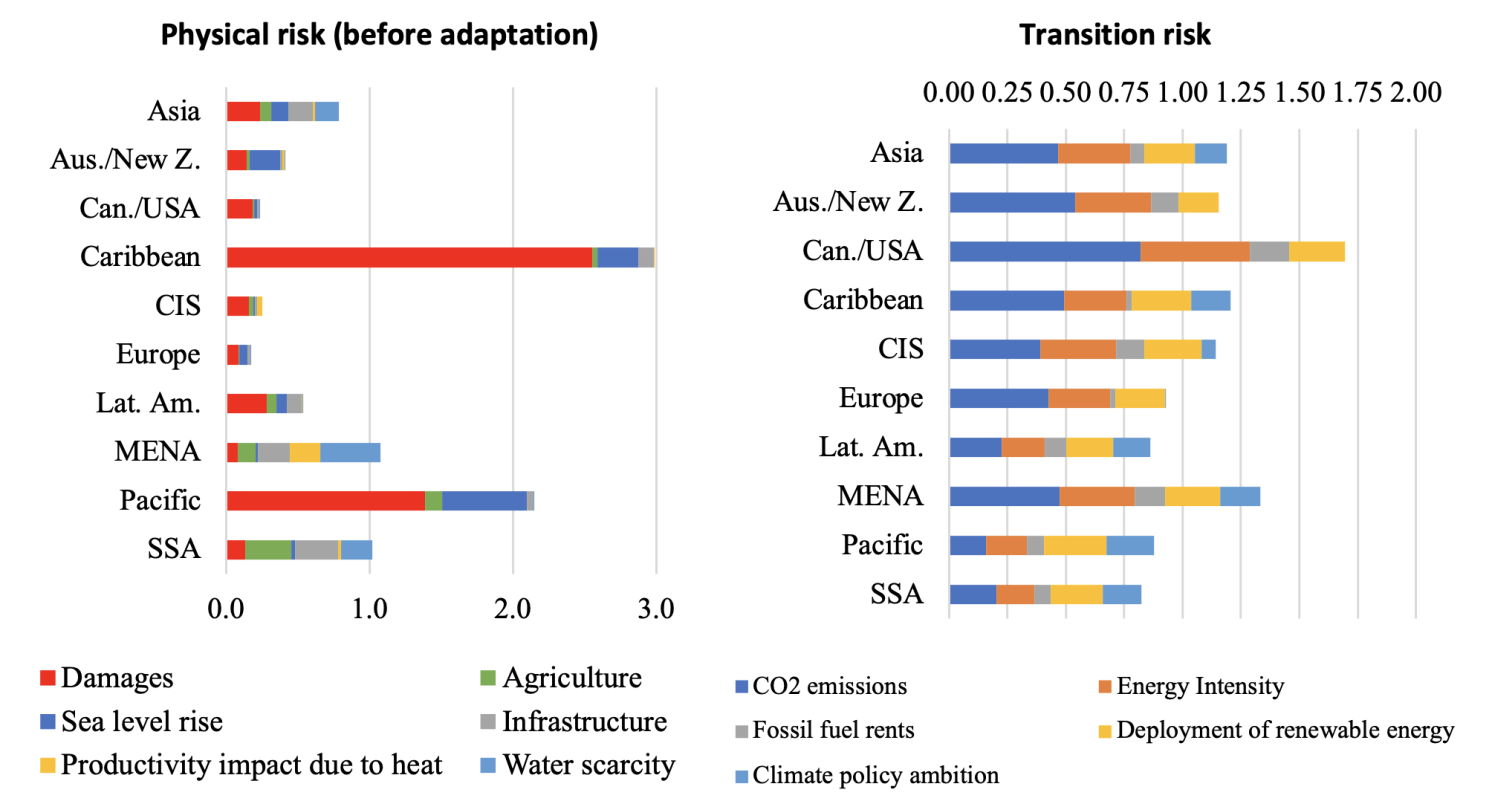

In a recent paper (Ferrazzi et al. 2025 ), we present an index to measure climate risk for over 170 countries, separately assessing physical and transition risk (on a relative basis – relative to other countries and relative to the size of their economies) while accounting for adaptation and mitigation capacity. The most relevant risk factors are carefully selected, and the related weights are assigned based on the literature and empirical evidence. Physical risk scores combine the following:

- acute risk: damages from extreme weather events, based on historical realisations (as a percentage of GDP, thus relative to the size of the economy);

- chronic risk: impact on agriculture, sea level rise, impact on infrastructures, impact on labour productivity due to heat, water scarcity (also as a percentage of GDP); and

- adaptation capacity, based on the economic ability to respond to shocks and the institutional capacity of the country (including rating, fiscal revenues, and governance indicators).

This approach, based on the relevance of impacts as a percentage of GDP, automatically provides the relative importance of each risk factor for each country, solving the issue of finding adequate weights.

Transition risk scores reflect the performance of countries in the past, today, and in the near future in the following:

- CO2 emissions, and the commitments to mitigate emissions;

- fossil fuel rents from coal, gas, and oil (as a percentage of GDP);

- deployment of renewable energy (as percentage of final energy consumption);

- energy intensity of economic activity; and

- climate policy ambition, based on the Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) required under the Paris Agreement.

The (very few) existing rankings use a large number of equally weighted indicators, implicitly assigning equal importance to numerous risk factors. Our approach, in contrast, is to select the relevant variables and assign proper weights, focusing on the next 5-10 years as the time horizon. Moreover, our approach incorporates factors that go beyond those typically considered in existing methodologies (chronic risk for physical risk or mitigation for transition risk, for instance) and relies only on publicly available data.

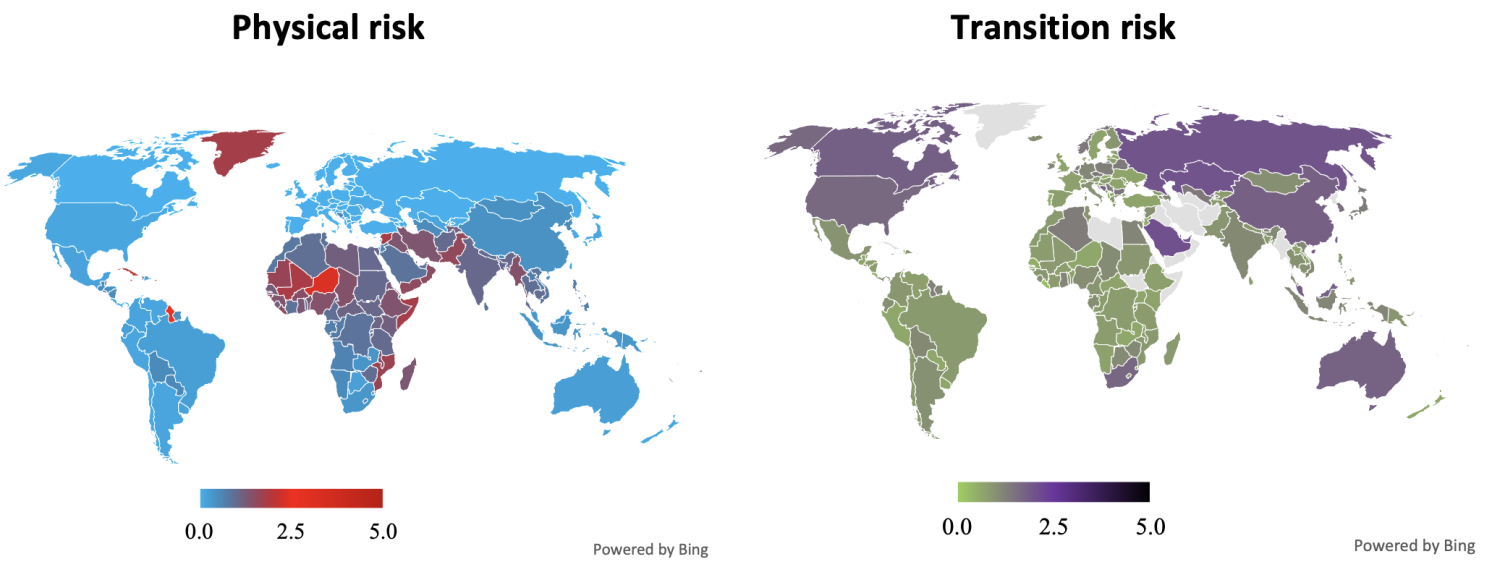

Who Is Most at Risk?

Despite climate change being at ‘code red’ level for the entire of humanity (IPCC 2021, Guterres 2021), each country is exposed to different risk intensities. Our climate risk country scores indicate that emerging and developing economies are most exposed to physical risk – in particular, to acute physical events (hurricanes and storms, floods, fires), sea level rise, and high temperatures. In general, emerging and developing economies are more exposed to higher temperatures (as additional increases of temperatures in already hot environments impact human activities) and to agricultural losses (which are the most dependent on weather conditions). These countries are also less able to adapt (i.e. to protect themselves from the effects of weather). Transition risk is more relevant for fossil fuel producers and wealthier countries which need to reduce emissions, and for those countries that are less prepared for the transition to net zero in terms of energy efficiency and deployment of renewable energy.

Figure 1 Contribution of risk factors

Note: Non-weighted average across countries. Global average of the scores (including adaptation) is 1.

Figure 2 Physical and transition risk by country

Note: Caribbean and Pacific (not clearly visible in the above map due to the size of the countries) face high physical risks and, respectively, high and elevated transition risks. Global average of the scores is 1 for both physical and transition risk.

Conclusion

Summarising a country’s climate risks into a score is a complex task that requires careful decisions regarding the objective, time frame, risk factors, and level of granularity. The few climate change indices available rely on a large number of equally weighted factors (‘as much as you can find’) and assume they are all equally relevant. Our climate risk country scores instead identify the main risk factors and calibrate the weights based on the literature and econometric analysis.

Our climate risk scores for 170 countries confirm that climate risks are not evenly distributed. Emerging and developing economies are the more vulnerable to physical risk and hence need relevant investments in adaptation capacity. In contrast, we find that transition risks are higher for wealthier and fossil fuel-producing countries.

Our country-level climate change risk scores have a wide range of uses and implications. First, as climate risks intensify and regulatory requirements evolve, banks and international financial institutions can use these scores to support their risk management processes. Indeed, using an earlier vintage of our scores, Cappiello et al. (2025) confirm the relevance of climate risks – in particular, physical risks – for sovereign credit ratings. The scores can serve as a risk-management tool for sovereign counterparts but also as starting point for evaluating climate-related risks faced by firms and banks within a given country.

Second, our scores can also represent an opportunity to identify mitigation and adaptation priorities and related financing needs to enhance climate resilience.

Third, the results highlight the importance of international cooperation, as climate change is a broad-based phenomenon affecting countries across the globe and requires collective efforts.

Authors’ note: The views expressed here do not necessarily reflect the opinion of the European Investment Bank.

See original post for references

20250135-120625-economics-working-paper-2025-06-en

A fascinating post.

“Climate risks” is fine as a catch all, and there is definitely a need to evaluate climate change impacts over successive timescales.

As a highly generalised piece this Economics Working Paper does have some useful stuff, but I gave up two thirds of the way through as it is all too speculative, and places contestable numerical values on vague numbers.

The authors note :- ” In practice, to assess the climate risk for countries three approaches are followed: modelling, scenario analysis and (index-based) scores. Multidimensional macroeconomic models aim to evaluate the macro impacts of climate change.”

The authors are all economists not geographers, climate scientists, or environmental scientists, any of whom would be able to contribute more specialised and detailed knowledge, and certainly more methodological rigour.

The chosen criteria for physical climate change effects are mostly measured as GDP impacts.

Assessing ‘transition risk’ and placing a value on it using an indicator of “well-below 2°C” seems stunningly vague.

I do wonder whether the nation state provides the best boundaries for this impacts type of work. For example, loss of Himalayan glaciers and meltwater into the great Indian sub-continent’s river basins seriously affects Pakistan, India and Bangladesh in terms of their agriculture, but how Pakistan and India might negotiate their future competing water resource demands is unknowable.

The authors seem to agree:-

“Without a very detailed underlying local analysis, country-wide risk measures are necessarily a proxy.”

The authors then heavily qualify their report themselves:-

“At first sight it may be reasonable to believe that including more risk factors could provide a more accurate assessment. In practice, however, the value of additional risk factors is likely to diminish beyond a certain point, and once the most relevant ones are identified, gains in accuracy are minimal. Moreover, assigning equal weights to all risk factors lowers the relative weight of each factor, including the major ones, which beyond a certain point is bound to reduce the quality of the index.” Aye, right

Their third summary conclusion is an obvious trusim:-

“climate change is a broad-based phenomenon affecting countries across the globe and requires collective efforts” but is so anodyne it wouldn’t even get you close to a pass mark in the Scottish Higher Geography exam.

Personally, I would be more inclined to refer to the IPCC Climate Change Sixth Assessment Report of 2022 on Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability. for a general summary of where we are.

That working group had a more comprehensive range of environmental expertise and is much broader, looking at ecosystems, biodiversity, and human communities at global and regional levels.

The report moreorless just states the bleedin’ obvious, and I think it entirely appropriate that NC have filed this piece under ‘dubious statistics’.

When a paper requires this many assumptions and workarounds it seems largely pointless to me. I mean what does it actually add to the debate? If anything it is just an easy target for sceptics and those who want to push back against any change.

Regarding whether nation state boundaries is the appropriate boundary for analysis – I see in the graph above that “US/Canada” has zero, or as near to it as displayable on a graph, risk for water scarcity…. That might be true when you lump in the Great Lakes into the whole, but tell that to anyone in the US southwest.

And note Yves on national food self sufficiency as an unaccounted for factor of climate risk in the study.

I suppose as economists who focus on finance, they don’t realize that food unlike money does in fact grow on trees and other vegetative life forms utterly dependent on climatic conditions.

I am reminded of the prominent economist who a decade or so ago claimed that since climate change mostly affected outdoors activities and most of the GDP generating activities in rich countries takes place indoors, it would be more economic to do nothing. Just pay for the future costs out of the GDP increase!

Tried to search for it, but fuzzy memory of it and the state of search today conspired against it. But it was a thing seriously argued at the time. (My memory of the economist is USian with a long, Scandinavian name starting with an “N”. If it jolts someone elses memory.)

That would be William Nordhaus, who got a “Nobel” prize for this work.

That’s the one, thank you!

To refresh:

Nordhaus model is called DICE and is apparently quite popular among economists. So something to look out for in papers.

A number of European countries, some large, bordering or near the Mediterranean are not assessed in Appendix B of that report: France, Italy, Spain, Greece, Croatia, Slovenia, Cyprus, Malta — as well as Portugal — while just a few small others, such as Albania, Bosnia, and Montenegro — as well as Andorra — are. On the other side of the sea, the study also excludes Turkey, as well as Morocco.

Quite an odd choice, given that the Mediterranean region is undergoing quite a rapid climatic disruption.

Not an odd choice to exclude the Mediterranean if you look at this paper as a targeted sales pitch.

I’m not sure who the target is or what they intend to sell,perhaps virtual can openers…

I wonder how many can openers were assumed when writing this report?

“Don’t worry rich countries, it’s just the poors that will be affected by climate change.” -Exxon, BP, Shell & co.

Literally