This is Naked Capitalism fundraising week. 742 donors have already invested in our efforts to combat corruption and predatory conduct, particularly in the financial realm. Please join us and participate via our donation page, which shows how to give via check, credit card, debit card, PayPal, Clover, or Wise. Read about why we’re doing this fundraiser, what we’ve accomplished in the last year, and our current goal, supporting our expanded daily Links

Yves here. Sometimes I feel like a dope. While some types of workers clearly have uncertain overall pay, like taxi drivers, gig workers, and employees who have tips as a significant portion of their earnings, it did not occur to me how many other hourly workers also suffer from having their employers often change how much time they want them to put in for a given week or month. The fact that precarity of income is that significant even among those who look like they have “regular” jobs also helps explain why the near-poor are so close to desperation. In the old days of my youth, a low wage worker who was careful about his spending could rent an apartment cheaply enough that he could save enough to buy a used car in well under a year. Now the fact that rents are high and most cars are purchased with loans give most workers a much high base level of expenses that they are only a bad income month away from living in their car or on the street.

By Peter Ganong; Pascal Noel Patterson, Assistant Professor of Economics Booth School Of Business, University Of Chicago; Faculty Research Fellow National Bureau Of Economic Research (NBER); Joseph Vavra, Assistant Professor of Economics at the Booth School of Business University Of Chicago; and Alex Weinberg. Originally published at VoxEU

Over the past decade, cities and states in the US have enacted ‘fair workweek’ laws to stabilise worker schedules. This column uses administrative data on US workers’ paycheques and firms’ payrolls to document considerable monthly fluctuations in earnings. Pay instability is widespread, disproportionately hits lower‑paid hourly workers, and is largely driven by firms’ labour demand rather than worker-related determinants such as childcare demands. These fluctuations represent genuine, welfare-relevant risk that materially shapes household decisions and has attendant effects on the economy.

Over the past decade, cities and states have enacted ‘fair workweek’ laws to stabilise worker schedules. New York City’s 2017 Fair Work Week Law requires employers in the fast-food industry to provide regular schedules at the start of employment and give two weeks’ notice for any changes, with worker consent and premium pay required for modifications (Pickens and Sojourner 2025). Chicago requires employers to provide 14 days’ advance notice of employees’ schedules but provides exceptions for events outside of employer control, such as supplier delays or unexpected demand surges (City of Chicago 2019). Los Angeles, Philadelphia, San Francisco, Seattle, and other local governments have enacted or are considering similar regulations.

These policy debates turn on empirical questions: how prevalent is pay volatility, and do workers view these fluctuations as harmful? If earnings instability is widespread and unwelcome, regulations on scheduling practices could improve worker welfare. If fluctuations are rare and operationally necessary, such rules could harm business efficiency without helping workers.

In Ganong et al. (2025), we document that pay volatility is not only pervasive but also profoundly unequal – concentrated among lower-paid workers. Hourly workers, who tend to be lower-income and more financially vulnerable, face far greater earnings swings than their salaried counterparts. For the 60% of the US workforce paid by the hour, these fluctuations shape spending decisions, drive job turnover, and fundamentally alter the experience of work.

Prior research using annual data has documented earnings risk over workers’ careers (Song et al. 2015, Moffitt and Zhang 2018, McKinney and Abowd 2023, Pruitt and Turner 2020). Our study highlights the causes and consequences of monthly income fluctuations, which are invisible in the annual data.

Payroll Data Show Workers Experience Considerable Monthly Fluctuations in Earnings

We use comprehensive administrative data from workers (via paycheque deposits into Chase bank accounts) and firms (via a payroll processor) to document considerable monthly fluctuations in earnings. Monthly earnings volatility is substantial. In about three-quarters of months, workers receive a different amount of pay than they received the prior month. The median month has a change of 5%, and in one-quarter of months, the change in pay is at least 17%.

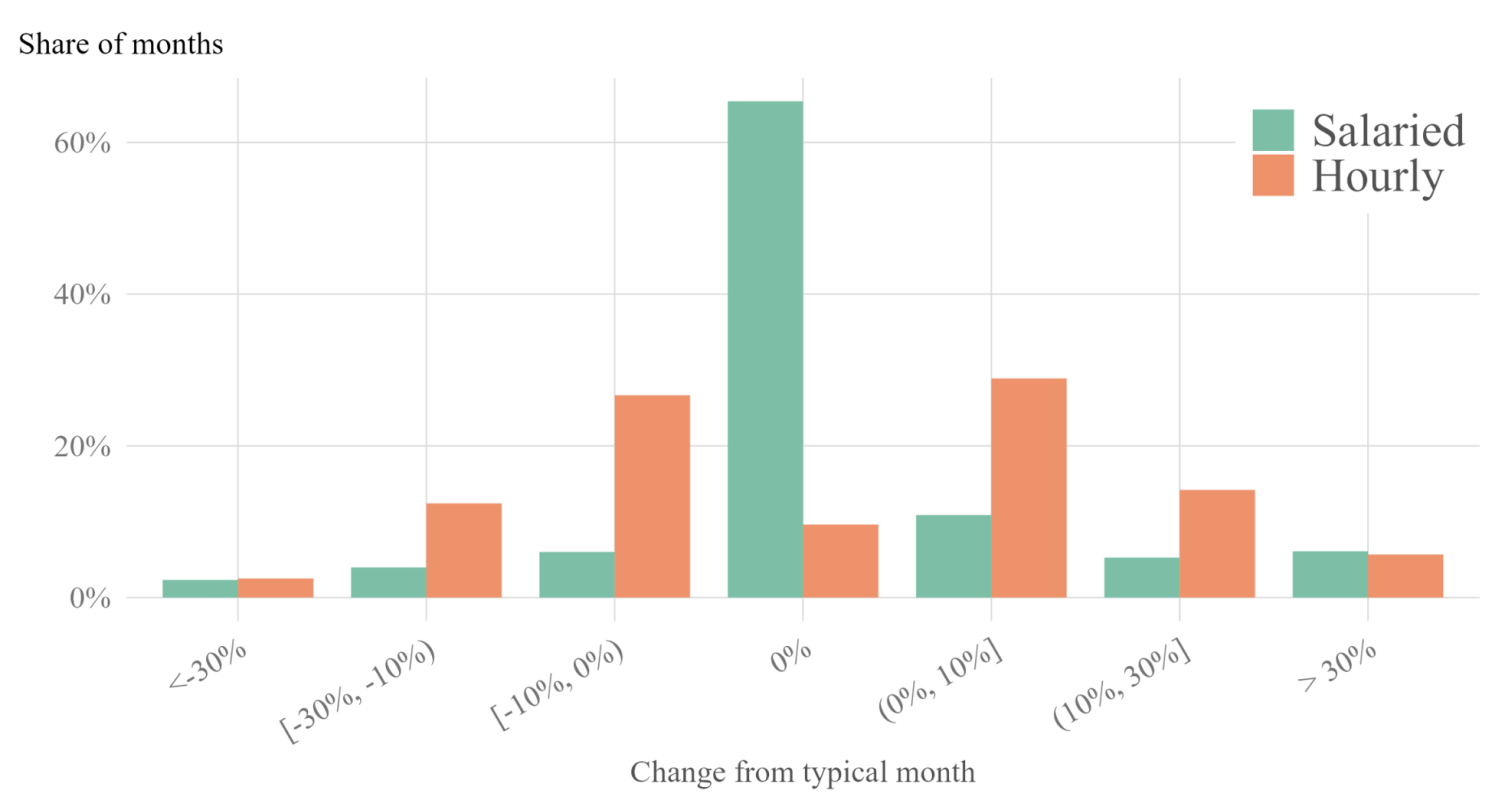

This volatility is concentrated among hourly workers. Figure 1 illustrates this heterogeneity in earnings volatility between salaried and hourly workers. For the majority of months, there is no change in earnings for salaried workers. In contrast, for hourly workers, no change in monthly earnings is a rare outcome.

Figure 1 Heterogeneity of earnings volatility

Notes: This histogram shows the distribution of the change in earnings for salaried and hourly workers with continuing employment. Because the number of paycheques varies from month to month, in this plot, the change in earnings is measured in terms of average monthly pay per paycheque. Specifically, the volatility estimate is calculated as the per-cent change in earnings in the current month from the median of the earnings in the three months prior.

These findings raise two further important questions. Why do hours move from month to month? And does this instability matter for worker welfare?

Firms Play an Important Role in Driving Monthly Earnings Volatility

We provide evidence that worker-related determinants such as temporary unpaid leave, childcare demands, and seasonal fluctuations do not explain earnings instability; rather, firms are the key to explaining changes in worker hours. Consequently, a meaningful share of this instability is imposed on the worker and is outside their control.

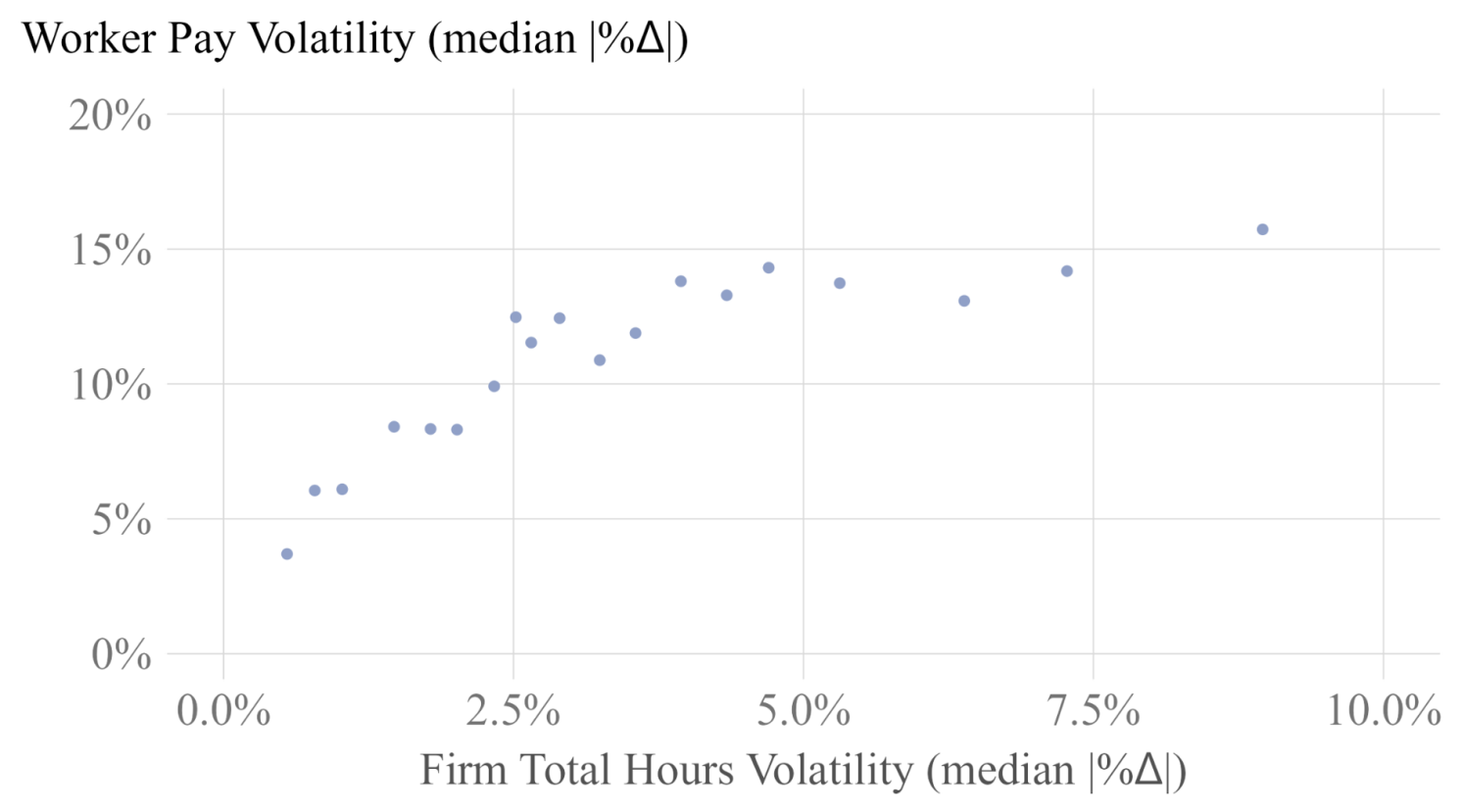

The relationship between the volatility of the firm’s demand for labour – measured as the change in total firm hours – and the volatility of worker pay is shown in Figure 2. There is a positive relationship between firm labour-demand volatility and worker pay volatility; in other words, larger changes in the total amount of hours worked by all employees are associated with larger changes in individual worker pay.

Figure 2 Relationship between firm-level volatility and individual worker volatility

Notes: This figure shows the relationship between firm total-hours volatility and individual worker pay volatility. Firm total-hours volatility is measured by taking the sum of hours for all workers at the firm and computing the median absolute monthly change. Individual worker pay volatility is measured by taking the median absolute monthly change for each worker at the firm. Each dot represents the average individual worker volatility for a group of firms with similar firm-hours volatility.

Income Volatility Causes Spending Volatility

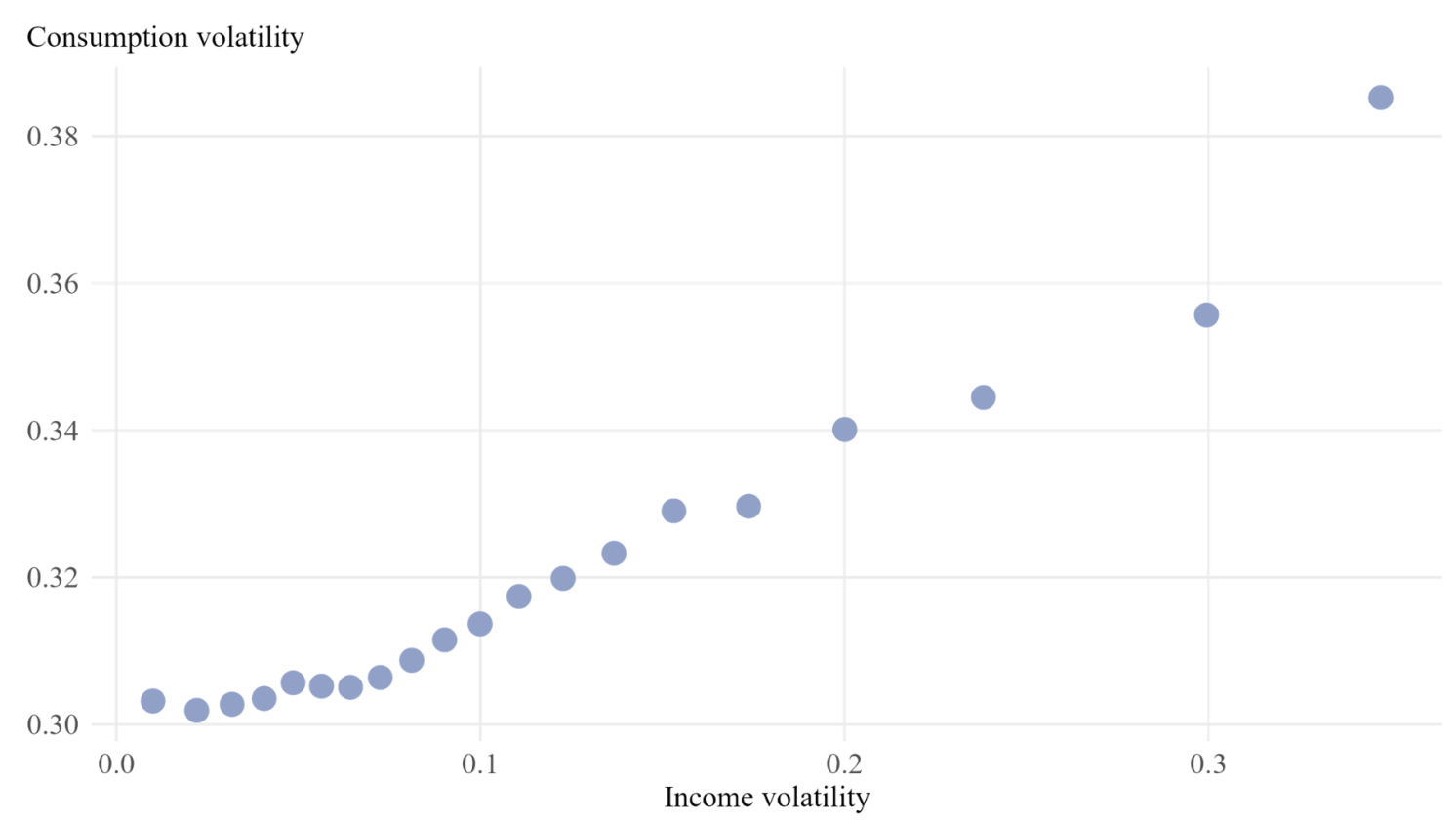

Earnings instability affects workers’ wellbeing in two ways. First, using bank-account data, we show that income volatility causes spending volatility. Spending volatility increases when workers move to higher-volatility firms (Figure 3).

Figure 3 Relationship between income and spending volatility

Notes: This figure shows the relationship between individual volatility of monthly income and monthly spending. The volatility measure is the individual’s median absolute change from the prior month. Consumption is measured as spending on non-durable goods and services, using bank-account data. Each dot represents the average consumption volatility for a group of individuals with similar income volatility.

Second, we show that hourly workers are more likely to quit high-volatility jobs, and firm volatility affects quit rates of hourly workers much more than salaried workers in the same firm.

Given that the above volatility is costly to workers, we seek to understand how much workers would pay to avoid earnings volatility. We combine the empirical estimates discussed above with standard economic models of the labour market to price how much workers dislike volatility. The median hourly worker would forgo 4%–11% of their income to attain the more stable income of a median salaried worker. Lower-income workers, who face the highest volatility, would trade an even higher fraction of their earnings for the stability of a salaried position.

Our work shows that workers dislike income volatility, but further work is necessary to understand whether firm scheduling flexibility serves essential business needs.

Bottom line: Workers face substantial monthly earnings risk that, to this point, has been missed when analysing annual data. This risk is borne primarily by relatively low-income, hourly workers and is largely driven by fluctuations in firms’ labour demand, which induces substantial costs on affected workers. This column shows that these earnings fluctuations represent genuine, welfare-relevant risk that materially shapes household decisions and has attendant effects on the economy.

See original post for references

Workers who need to be on the good side of both their employers to get the work hours assigned dare not endorse unions.

Due to the Federal medical insurance requirement for workers who work more than 30 hours/week, many hourly workers are now part-time and work 28 hours as week at most. If you want to find a second job, an unstable schedule makes it nearly impossible. This instability is part of the reason that flexible side hustles are now the thing. Ride-share, delivery services, can be used flexible to fill in the gaps. However, trying to take care of kids ir even have a social life will be difficult in the extreme.

The people I know who deal with this are adult restaurant workers. Several waitresses I know are working shifts at 2 different restaurants to try to make ends meet. As long as the hours/schedule are stable, they can get by, any shift or cuts in hours causes chaos.

I’ll make an important assumption: the level of income and the volatility of income can be, and often are, uncorrelated.

Assuming that total income over a given period, say a year, is adequate, then weekly or monthly expenses can be determined and budgeted for the next period or year, in this case.

Income received is deposited in a bank account, or an envelope. Budgeted expenses are extracted and placed in another account or envelope. Volatility is irrelevant in this model as long as the periodic expenses, and income level, are relatively stable.

I know this works. For me, it was the way I managed my life over 50 years of working in a volatile income environment.

If work is precarious, of course, income volatility becomes more manageable, but that only prolongs the ability to weather the periods without income. That also presumes that the work doesn’t have greater expenses. Also, if income is volatile, that means it is unpredictable, which impacts planning.

Glad it worked for you for your 50 years but I’m not sure this one anecdote justifies your argument.

I would add one other assumption: Expenses, per period, must be less than periodic income. If expenses are higher than income, those expenses must be reduced. There is no point in managing income volatility risk if the smoothed out income is less than smoothed expenses.

Managing cash in flows and outflows may be difficult, but it is not impossible.

Volatile means likely to change suddenly and unexpectedly. The income environment you are describing is not volatile. What you are describing is an income environment that is variable, but stable, and therefore predictable. I work in such an income environment. At the beginning of each year, I can make a reasonably accurate prediction of how much I will make for the year, and how much I will earn for each month of the year, based on my knowledge of when the work will be performed. The swings in income from high earning to low earning months are substantial, but predictable, and therefore stable over time. In this type of income environment, your system will work, provided of course that your total annual earnings are adequate for meeting your living expenses, healthcare and saving for old age when your ability to work diminishes.

However, if you are a wage earner whose hourly pay barely exceeds subsistence level based on a 40 hour work week, and whose work schedule and hours worked can swing significantly from week to week, that’s an entirely different situation altogether. The problems of this situation, especially if the wage earner doesn’t qualify as a full-time employee lawfully entitled to employee benefits, far exceed the capability of your plan to solve.

As someone who works on the data analytics side of a bank…. I can confirm these findings. Pay for many people is highly variable, and that’s based upon those with direct deposit. Paycheck folks are likely even more variable.

On a personal note… as a teen and early 20-something I could work 50-60 hours a week on a farm or in construction during the summer, but winter months would be hard to get many hours unless you were hired to work all year & even those people often worked less than 40 hours a week in deep winter months.

As someone who has actively managed scheduling for several hundred workers, this is 100% a management issue. We used to hold managers accountable for bad management, but it seem like they all get a free pass these days. If my guys are seeing swings of more than a few hours a week, we are doing it wrong.

Contingent hours, on-call hours, should be full worked hours. End of problem. But there is no way on the surface of the earth that our legislature will change the definition.