Yves here. Even though anyone who took a basic economics class learned that monopolists and oligopolists set prices higher than sellers do in competitive market, pols, pundits, and the press are bizarrely loath to point that out in real world situations. They seem to have been brainwashed that larger = more efficient, and that those efficiency savings will be in part passed on to customers. The post below is yet another demonstration that the companies in dominant positions can and do set dictate prices, and do so in times when inflation starts ticking up. It effectively proves the incorrectly-derided “greedflation” thesis.

Yet the authors made a point of not saying anything so direct. The original article headline was The granular origins of inflation. Since when does “granular” evoke “big”? Just read the overview paragraph below and see how they bafflegab their important findings.

By Santiago Alvarez-Blaser; Raphael Auer, Head, BISIH Eurosystem Centre Bank For International Settlements; Sarah Lein, Research Network Fellow CESifo; Faculty Member Swiss Finance Institute; Full Professor of Macroeconomics University Of Basel; and Andrei Levchenko, John W. Sweetland Professor of International Economics University of Michigan, Ann Arbor Originally published at VoxEU

Textbook monetary economics views inflation as fundamentally driven by aggregate shocks, such as money supply or policy rates. This column presents empirical evidence that inflation is highly granular – it is significantly influenced by the prices set by a small number of large firms. Based on an analysis of 2.9 billion barcode-level transactions spanning 16 economies, it shows that firm-level idiosyncratic shocks account for a substantial share of inflation variability in advanced economies. Granular forces were also a key driver of the 2021–22 inflation shock and are shown to slow down the transmission of monetary policy.

What is the role of large firms in aggregate inflation, and what are the causes and implications of such ‘inflation granularity’? Textbook monetary economics views inflation as fundamentally driven by aggregate shocks, such as money supply or policy rates (Woodford 2003, Galí 2015). While the literature models rich micro-level price adjustment heterogeneities, idiosyncratic firm behaviour is typically integrated out, leaving no role for individual firms in aggregate inflation. At the same time, following Gabaix’s (2011) seminal contribution, an influential strand of the macro literature has modelled theoretically and documented empirically that shocks to individual (large) firms can generate aggregate fluctuations.

In recent research (Alvarez-Blaser et al. 2025), we shed light on this issue. We analyse a multi-country home-scan dataset spanning roughly 2.9 billion barcode-level transactions and 16 advanced and emerging economies. Each item is linked to a producing firm and a product category, as well as a retailer.

We start by showing that the preconditions for granularity are present in the data, as expenditure is highly concentrated: in the average advanced economy, the top ten firms account for about 41% of sales and the top ten categories for around 48%. There is also a high degree of synchronisation of price changes within multi-product firms and within categories.

We next develop an additive decomposition of aggregate inflation into a macro component (i.e. country-level unweighted averages) plus granular residuals at the firm and category levels. Our decomposition generalises the conventional granular residual setup (e.g. Gabaix 2011, di Giovanni et al. 2014, Gabaix and Koijen 2024) in two dimensions. First, we allow for multiple non-nested dimensions of granularity (firms, categories, and, in an extension, retailers). Second, a granular residual can arise either from idiosyncratic shocks to large firms or from differential responses of large firms to common shocks. 1 Our notion of granular residual explicitly allows for both of these driving forces. We document which one is more powerful in our context.

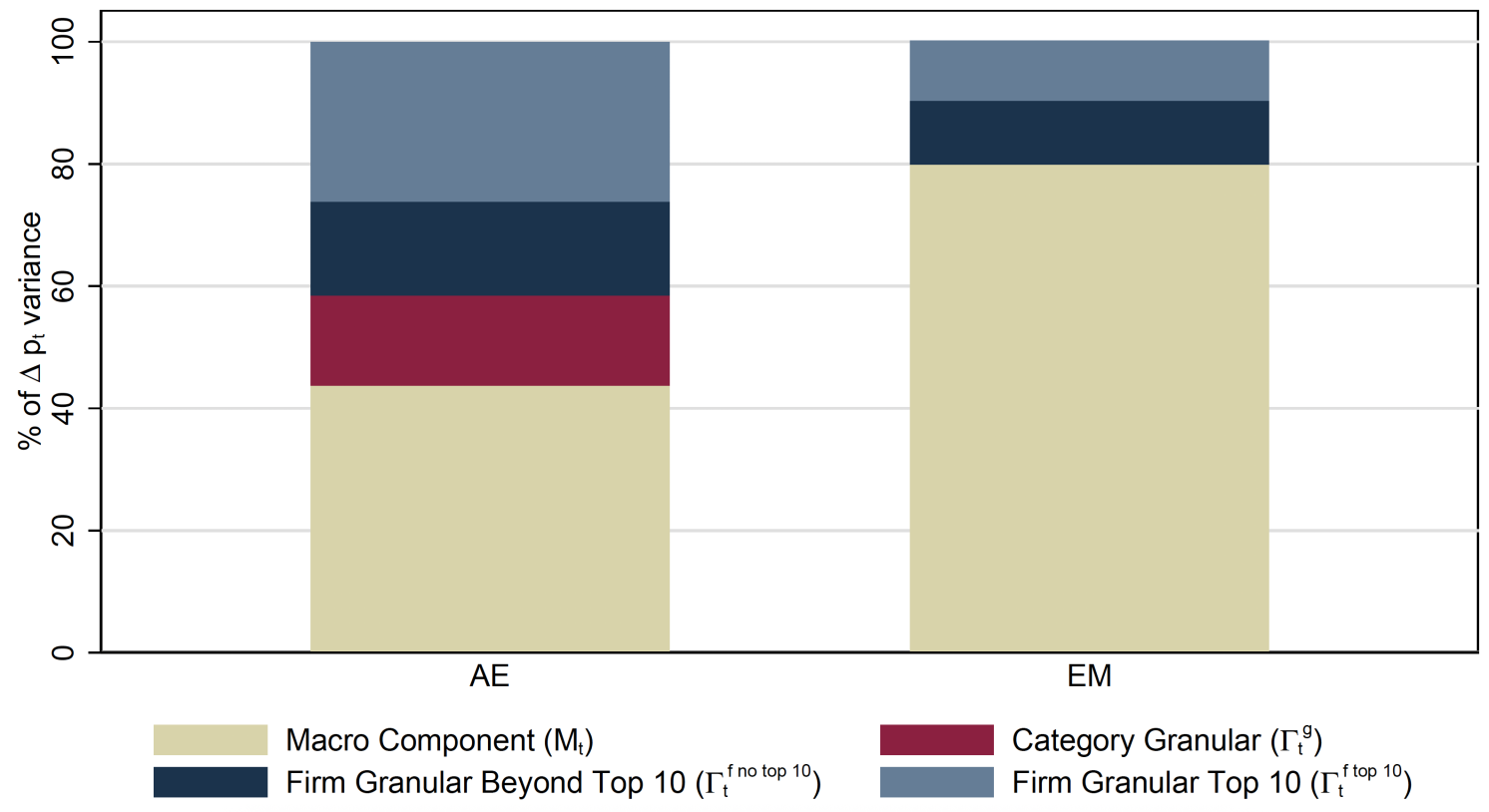

Figure 1 displays the high-level results of our analysis. At the macro level, the firm and category granular components account for 56% of the inflation variance in advanced economies over the 2005-2020 period (see the left-hand column of Figure 1). The firm granular residual is relatively more important, explaining some 41% of inflation variance. Twenty-six percentage points (dark red) are accounted for by the ten largest firms alone, and the remaining 15 percentage points by large firms that are not in the top ten (light red). The category granular residual accounts for an additional 15% of inflation variance (yellow area). We next decompose the granular residuals into the components due to the differential responsiveness to common shocks, and the idiosyncratic shocks. The firm granular residual is predominantly driven by idiosyncratic shocks. By contrast, more than half of the variability in the category granular residual is due to the categories’ differential responsiveness to common shocks.

Figure 1 Contributions of granular components to retail inflation variation

Note: This figure displays the share of the variance of aggregate year-on-year inflation accounted for by each component.

Granularities are a less important in emerging markets (see the right-hand column of Figure 1), where inflation is higher on average and market shares are less concentrated: the combined firm and category residual explains about 20% of inflation variance.

Market Share Concentration and Inflation Granularity

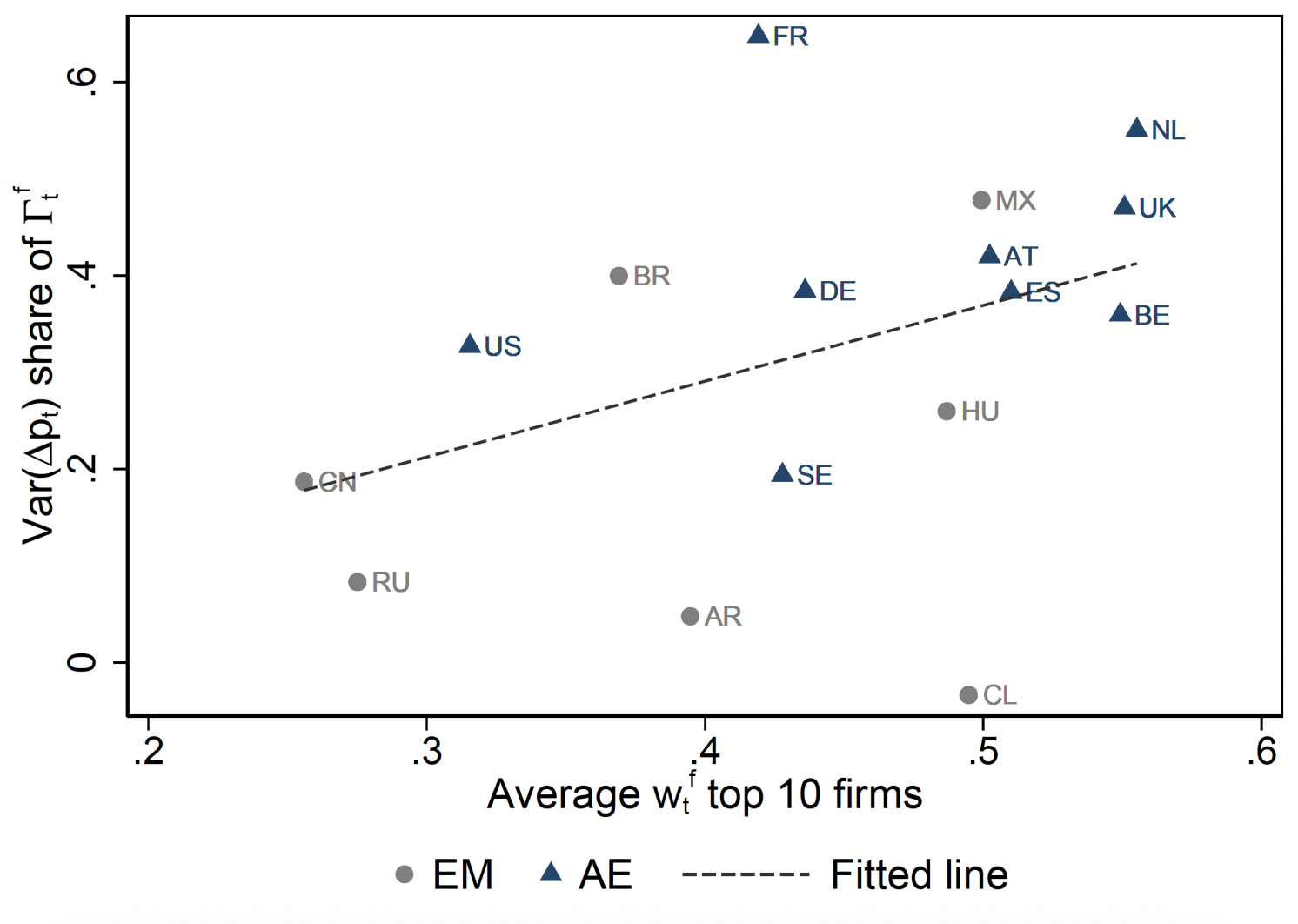

We next investigate how the cross-country differences in inflation granularity relate to market concentration in these countries. In particular, we relate the explanatory power of granular residuals to the market shares of the top firms. Figure 2 displays a scatterplot of the variance share in total inflation accounted for by the top ten firms against the average market share of the top ten firms in each country. There is a positive and statistically significant relationship, suggesting that granular effects are stronger in countries with higher market concentration.

Figure 2 Granularity and market concentration

Note: The figure displays a scatterplot of the share of the variance of aggregate year-on-year inflation accounted by the firm granular residual against the expenditure share of top 10 firms. The dashed line is a linear fit with a slope of 0.78 (robust standard error of 0.31) and R-squared of 0.16 (N=16)

This correlation suggests that trends in market concentration, as documented for example in Autor et al. (2020), may coincide with an increasing role of firm granularities in aggregate inflation dynamics.

The 2021–22 Inflation Surge

During the post-pandemic period, granular forces increased in relative importance in advanced economies. On average, the firm granular component accounts for a sizable fraction of the 2021–22 inflation rate, reflecting both idiosyncratic shocks and heightened sensitivity of large firms to common disturbances (e.g. supply bottlenecks, energy). This again highlights the role of large firms and multi-product price synchronization in amplifying macro shocks.

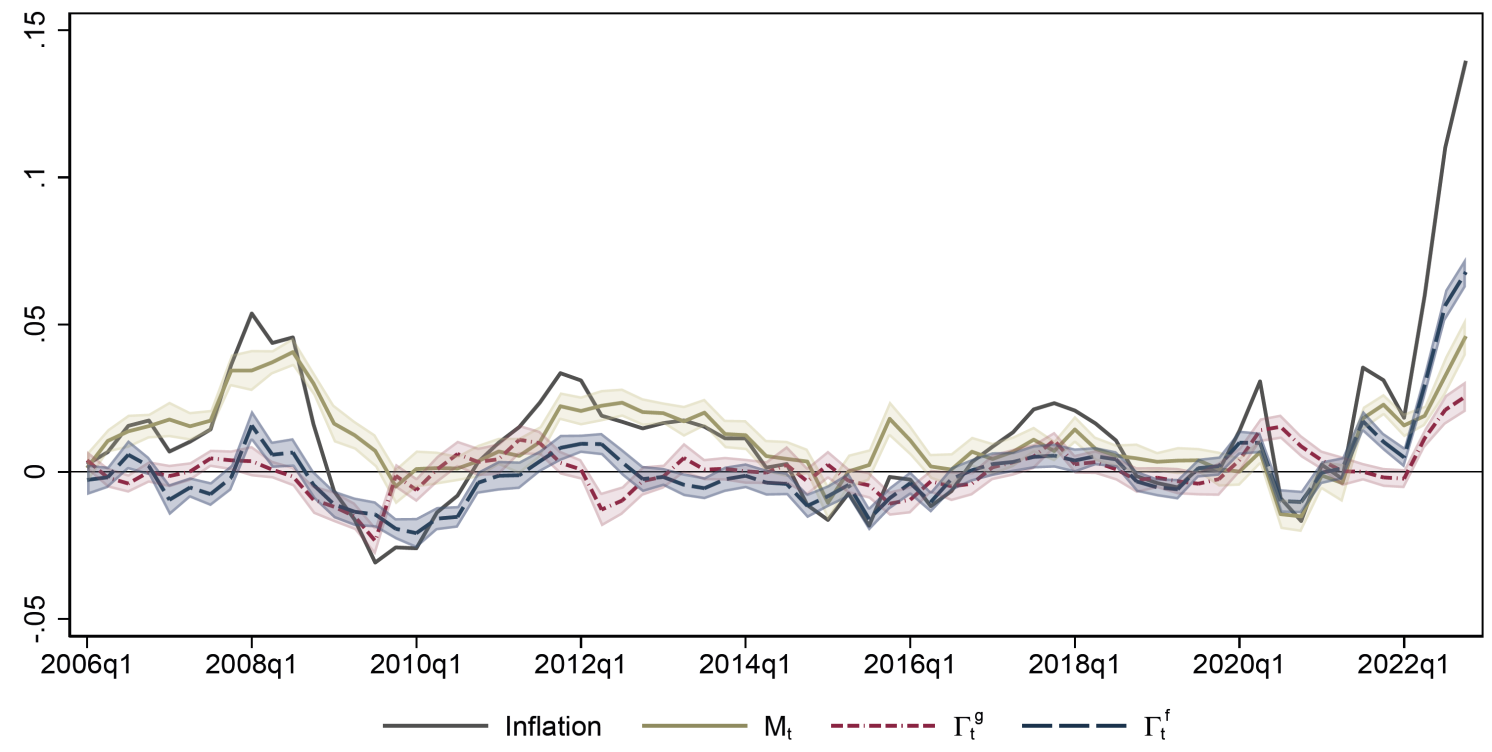

Figure 3 exemplifies these findings for Germany. Its shows overall inflation (solid line) split into the unweighted average (the macro component, dashed line) and the granular components (the sum of the firm and sectoral one). The figure shows that during the inflation surge, granular forces played a larger role.

Figure 3 Germany: Aggregate retail inflation and granular components – retailer dimension

Note: This figure displays the aggregate year-on-year inflation and each component. The rest of the countries and figures showing all available years can be found in the main paper.

Implications for Monetary Policy Effectiveness

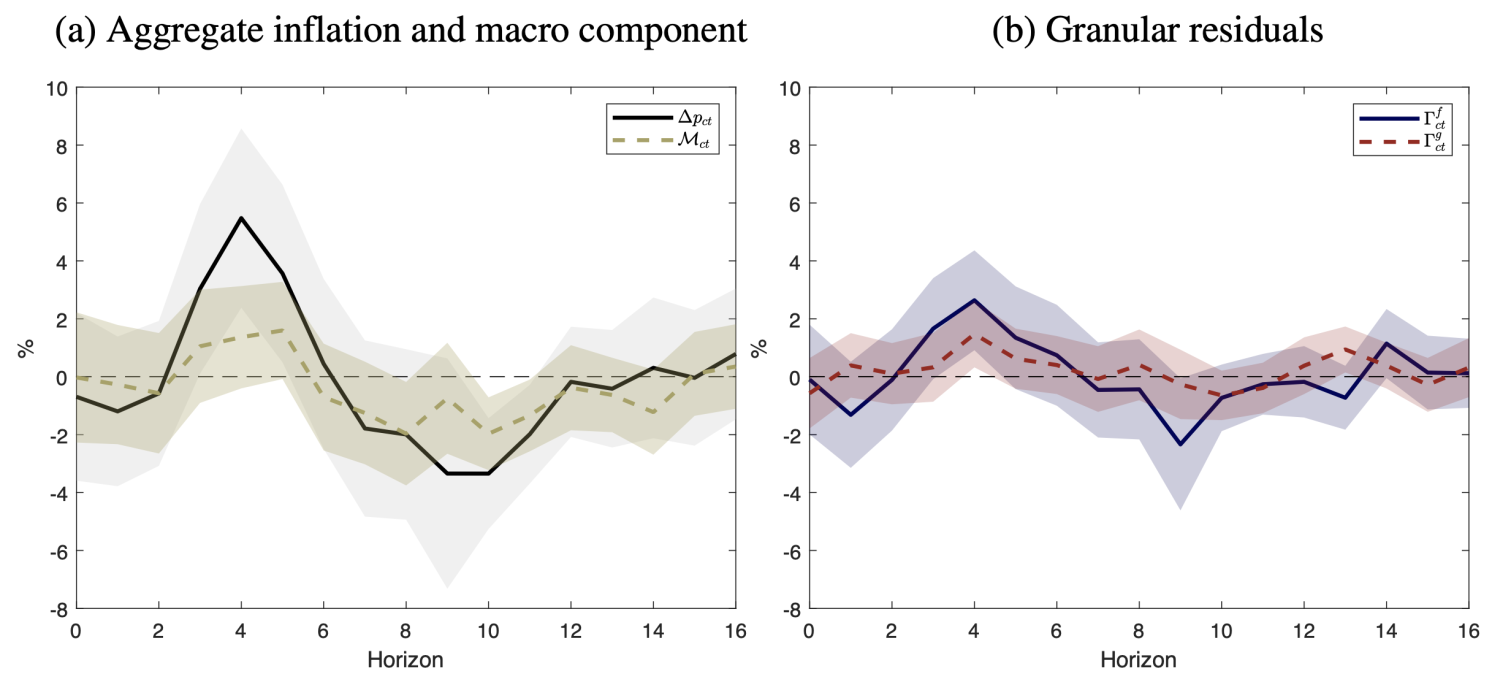

A key policy result is that granularity alters the impulse response of inflation to contractionary monetary policy. In local projection estimates for the US and the euro area, aggregate inflation displays a short-run ‘price puzzle’, consistent with earlier evidence such as Christiano et al. (1999). This initial increase is almost entirely driven by the granular components, which together account for roughly three-quarters of the short-run rise. By contrast, the macro component does not raise inflation in the year following the monetary policy shock – it shows no significant response for about five quarters and then declines, in line with standard theoretical predictions. This implies that market concentration and the pricing behaviour of large firms can delay disinflation, weakening near-term transmission. Put differently, in more concentrated environments, monetary non-neutrality is shaped by the behaviour of a small set of large price-setters whose pass-through of financing and input-cost shocks may be stronger.

Figure 4 Impulse response functions for aggregate inflation and components

Notes: Panel (a) shows the quarterly local projection results for all components aggregated into overall year-on-year inflation, as well as for the macro component alone. Panel (b) presents the corresponding results for the firm-level and category-level granular residuals. Shaded areas indicate 90% confidence intervals based on HAC standard errors.

Conclusion

We show that inflation in advanced economies is highly granular, i.e. it is significantly influenced by the prices set by a small number of large firms. In the cross-section of countries, granular residuals are less important in economies with less concentrated market shares and higher inflation, such as emerging markets. Granular residuals contributed to the post-COVID inflation surge, with the firm-level component accounting for roughly one-third of the 2021-2022 inflation in advanced economies.

Overall, these findings highlight that granular factors beyond traditional macroeconomic determinants matter greatly in shaping inflation, which also affects the effectiveness of monetary policy and hence the conduct of monetary policy. An operational takeaway is that granular price microdata of large firms and products are a valuable input for inflation nowcasting. The ECB’s Daily Price dataset and the BIS Innovation Hub’s Project Spectrum are examples of efforts to develop tools for real-time analytics and nowcasting based on detailed prices, improving signal extraction from inflation (BIS Innovation Hub 2025).

______

- Since we observe prices but not marginal costs, we cannot separate the observed price changes into markup adjustments versus cost changes. Thus, our findings do not directly speak to a recent debate on whether large firms had disproportionately raised their markups during the 2021-22 inflation surge (i.e. the so-called ‘greedflation’ or ‘seller’s inflation’ debate). Available empirical evidence suggests that markup adjustment was not a major driver in the inflation surge (e.g. Alvarez-Blaser et al. 2024).

See original post for references

Textbook monetary economics views inflation as fundamentally driven by aggregate shocks, such as money supply or policy rates. Oh, monetary economics. Then there is the Joan Robinson textbook The Economics of Imperfect Competition. Apparently and artifact now. The Neo-classicists…hoist on their own petard.

In The Affluent Society Galbraith describes how in the post war economy, oligopolistic companies first set next years prices, then negotiated next years wages and then when wage increases were public they made next years wages public.

For me that made something click. You know the common claim that companies pass on wage increases? But who can just pass on increases, weren’t prices supposed to be set by supply and demand? If companies has pricing power why would the wage increase matter except as a story to avoid protests?

I am shocked to learn that Hayek’s beloved businesses which, through effective competition and the efficiencies scaling up brings making it possible to offer higher quality goods at lower prices to the ultimate benefit of the consumer, relies on an incorrect assessment of the real world. Perhaps this is why there is so much poverty going around.

“Granularity”? I don’t recall that term. It must be fairly new.. It is not in my copy of J is for Junk Economics, (Hudson, 2017). I did chuckle with sarcasm while reading this term several times in the article.

But, I do recall an old-fashioned economics term rarely used nowadays: collusion (and price-fixing). This sort of thing may be hard to prove, but there appears to be lots circumstantial evidence. “Vertical integration”, monopsony, oligopoly, all appear to be working hand-in-hand to help price-gouging. (pun intended?)

Example: why are food prices higher in California when most of that food is produced in California?

Then another situation comes to mind is where a “regulated” monopoly (see PG&E) has captured (bribed) the regulators to look the other way while they price-gouge a captive market. I know I repeat the term ad nauseam but institutionalized corruption is at play in a big way.

More than just several times: I may have missed one, but I counted the use of “granular” or “granularity” 24 times in this short article. The authors believe that use of such jargon and bafflegab lends to credibility? Or maybe I’m just a pedantic codger who isn’t up to speed on the latest NewSpeak terms.

JFYI, publicly-owned SMUD (Sacramento Municipal Utility District) is adjacent to PG&E and is 35% cheaper. It’s C-suite is also not consulting with criminal attorneys about the possibility of facing charges of negligent homicide for their skimping on maintenance starting forest fires (that killed people).

Public ownership–it’s cheaper and better managed.

All industries are essentially cartels. It’s the five families for the win all over the economy.

Anti monopoly law was inevitable for us steel. Eventually same for these d-bags. Maybe even in my lifetime at this rate.

This time the boots to the throat economy is not different.

All my life, inflation has been presented as a natural force like gravity. All my life, I have never seen a period of time where there has been disinflation. All my life, I have been wondering about this mystery.

Prices are not set in a vacuum based on supply and demand. Prices are set by firms who are trying to maximize their margin. They know that small changes in prices tend to be absorbed by consumers and therefore are incentivized to raise prices slightly over time. Due to consolidation of industries and collusion, customers have very little recourse but to pay the higher price if they want those goods. Instead, their (relative) strength lies in pushing for higher wages. Thusly, prices and wages trend upward over time, although not typically in concert (see my post below).

Not only do monopolies charge higher margin, but they price discriminate. It’s befuddling that we do not consider the current versions of price discrimination, now common, conclusive evidence of monopoly.

That’s an awful lot of words to avoid saying two — economic rents …

I’m not sure who originally said it, but it sticks with me. Inflation is a distribution problem. If wages and prices all went up in conjunction, it would be annoying but not really a huge deal. Inflation is a problem because prices go up faster than wages, so most people see their purchasing power eroded. But that money all has to go somewhere (every purchase is someone else’s income). So, if most people are experiencing a reduction in purchasing power, some few are seeing massive increases.