Yves here. Below, Rajiv Sethi analyzes a big Polymaket position, betting that the US would attack Iran. That did not happen, making this look like a case of acting on inside information that turned out to be false due to Trump deciding at the last minute to stand off.

Or was it that? Sethi argues that this trader could still have made money by stimulating others to put on trades based on the assumption that the sudden move was based on special intel. But it could have been a rug pull with the original trader more than recouping his apparent losses.

Faking out other traders has long been seen as acceptable in the Wild West of foreign exchange and commodities markets where there is no notion of insider trading, but other games played. The biggest is front-running of customer orders, where the size of the ultimate trade (which could be spread across trading venues) or merely who placed it could have market-moving impact. Even though that is supposedly illegal even in FX and commodities, it is widely believed to happen. Some legendary trader were skilled at placing orders in a way that led other market participants to think they must be either acting in anticipation of placing a big customer order or actually putting part of one out there. Andy Kreiger, a foreign exchange trader at Salomon, then Bankers Trust, was seen by his counterparts at top foreign exchange options proprietary trader O’Connor & Associates as having a simply uncanny ability to wrong-foot other trader repeatedly.

By Rajiv Sethi, Professor of Economics, Barnard College, Columbia University; External Professor, Santa Fe Institute. Originally published at Imperfect Information

In my last post I discussed the case of a Polymarket trader who placed a series of well-timed bets on the ouster of Nicolás Maduro and made a profit of over $400,000 (on a $32,000 investment) in just a few days. What was unusual was not the quick profit or the high rate of return, but the fact that the account was opened just a couple of weeks before the raid, bet only on events related to Venezuela, and stopped trading once the Maduro contracts had been settled. This pattern of activity suggested to many observers that the trader had access to inside information, and coverage wasextensive.

Trading on Polymarket involves an unusual mix of public and private features—all transactions are visible on the blockchain, but the real world identities of most account holders are not known even to the exchange. This makes it easier for insiders to trade without detection, but also allows the public at large to look for activity that is suggestive of insider trading. Tools such as insider finder have been developed for precisely this purpose. The use of such tools can be lucrative because early and reliable identification of insider trading can allow outsiders to copy the trades before they have had significant price impact.

But consider the implications of this. If market participants are looking for patterns suggestive of insider trading in order to replicate these trades, there is money to be made by generating such patterns in the expectation that one’s trades will be aggressively copied. This mimicry will have a price impact, and the trader (wrongly) suspected of insider activity can then close out positions at a quick profit. This can be done very discreetly on Polymarket using separate wallets, so that the account making the initial move records a loss, while the profits accrue undetected elsewhere. This would be an example of spoofing.1

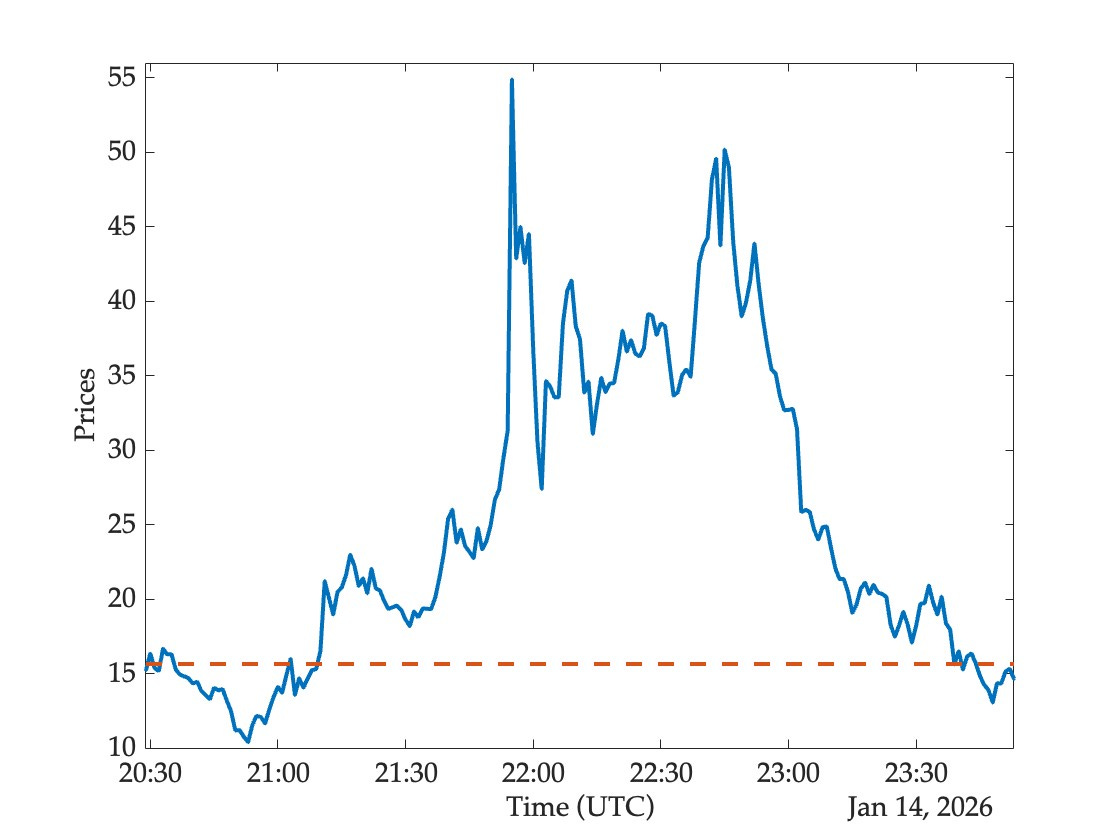

The possibility that this kind of thing might be happening occurred to me a couple of days ago when an account was flagged as a possible insider on social media. The activity here was even more clear-cut than in the Maduro case. The account was opened on January 14 and spent over $40,000 buying a quarter million contracts at an average price of 15.6 cents, betting that the United States would strike Iran on that very same day, by midnight on the East Coast. All trades were made between 8:29pm and 11:53pm UTC. Had an attack occurred, the trader would have made a profit of over $215,000 in a matter of hours. But there was no attack, and all shares expired worthless.

Had this trader’s bets paid off, I think it’s safe to say that they would have attracted significant media attention. But since they did not, the activity remained largely unnoticed and quickly forgotten. This is unfortunate. There is something to be learned from these transactions, although I can think of (at least) two quite different explanations for them.

One possibility is that a planned attack was postponed at the last minute, and the trader learned of the plan but not the reversal. This seems quite likely to me. But there’s an alternative possibility worth considering. Take a look at the price movements between the trader’s first contract purchase (at 8:29pm UTC) and the last (at 11:53pm UTC):2

The dashed horizontal line is at the average price paid by this trader. The total number of contracts traded during this window was above 5.58 million, and the price per contract rose as high as 55 cents. It would have been easy for this individual, using a different wallet, to have bet against an attack at prices that resulted in a significant profit overall—registering a loss in the account that was flagged but a much larger gain elsewhere.

The point is that spoofing can be profitable—if you can lead others to believe that you are trading on inside information, and this causes them to mimic your behavior, price movements can be amplified in ways that let you make substantial gains. This doesn’t require you to possess any inside information at all. The strategy relies only on a presumption among other market participants that insider trading is widespread on the platform.

Financial markets are complex adaptive systems in which prices are determined by the interaction of heterogeneous trading strategies. Furthermore, the ecology of strategies is never static; it evolves under pressure of differential payoffs. Some strategies (including insider trading) feed information to the market, others try to extract information from market data, and still others try to profit by trying to fool the extractive strategies.3 This can result in bubbles, momentum effects, excess volatility, and even a flash crash.

One of my favorite experimental papers in economics is Rosemarie Nagel’s study of guessing games, which revealed with great clarity that there are conditions under which certain standard equilibrium concepts predict poorly. The prototypical guessing game is simple—imagine a large group of players, each of whom privately chooses a number in the closed interval [0, 100]. The winner is the player whose choice is closest to half the average in the group as a whole, and if there is more than one winner the prize is shared equally among all.4

This game has a unique Nash equilibrium in which all players choose precisely zero, but this is neither descriptively accurate not prescriptively useful. Numbers close to zero are rarely chosen and never win; there is usually a distribution of responses with peaks at particular values, and the winning player often chooses something in the high teens. If you were playing with a group known to be familiar with Nagel’s findings (or with the post you are reading) you would probably choose something smaller. But even so, choosing zero or something very close to it would probably end in failure.

Such guessing games are sometimes called Keynesian beauty contests after a memorable and insightful passage in the General Theory. Keynes likened professional investment to newspaper competitions in which a prize is “awarded to the competitor whose choice most nearly corresponds to the average preferences of the competitors as a whole.” The result, according to Keynes, is that “we devote our intelligences to anticipating what average opinion expects the average opinion to be. And there are some, I believe, who practice the fourth, fifth and higher degrees.”

Financial markets in general, and prediction markets in particular, can be highly effective mechanisms for information aggregation. They can take account of novel sources of information and generate forecasts even under historically unprecedented conditions. But they are hardly perfect, and the evangelical zeal with which some have promoted them is not really warranted. The question of predictive accuracy relative to statistical models can only be settled empirically; one cannot reason one’s way to an answer. I don’t think it will take decades to resolve, as some have argued, but it will take some time and we are just getting started.5

__________

1 Insider trading, wash trading, and spoofing are all outlawed on Kalshi and other regulated exchanges. While the overall prevalence of insider trading and spoofing on Polymarket is not known, there is a procedure for detecting wash trading and this has been quite significantover certain periods.

2 I’m grateful to Allen Sirolly for providing me with data for this post.

3 My post on spoofing eventually led to an opinion piece in the New York Times.

4 I first encountered this game in a chapter by Mario Henrique Simonsen in a volume edited by Arrow, Anderson and Pines. I would recommend the entire volume to every graduate student in economics. The guessing game (and others like it) opened up exploration of alternative solution concepts that allow for bounded rationality.

5 I spoke with Michael Smerconish about some of these issues on his CNN show yesterday, and at greater length on his radio show a couple of days earlier. We covered a fair amount of ground in a relatively short time; here’s a short but quite substantive clip: