The Economist has managed to sink to an astonishing low in a new article, The “ChatGPT moment” has arrived for manufacturing. It has managed the impressive show of ignorance in a multi-page piece on the future of production of not once mentioning China, let alone the freakout in board rooms all across the West over China’s implementation dark factories and its lead in robotics and related technologies. Has The Economist been living under a rock?

There is no justification for its grotesque malpractice, of affirmatively making readers stupid. Information hounds trying to navigate propaganda-created halls of mirrors may have noticed that The Economist is a proud purveyor of howlers about the war in Ukraine, for instance, regularly depicting the Russian military and economy as badly run and on the verge of collapse. But The Economist is a card carrying member of the UK elite. The nation’s leadership is all in with Project Ukraine. So whether due to turning off their critical thinking abilities or viewing their patriotic duty as falling in with “Truth is the first casualty of war,” one can kinda-sorta understand why The Economist is not wont to defy the UK establishment and do real journalism on this topic.

But how is it possible to to have missed the panic among Western manufacturing companies, particularly in the auto industry, about the proliferation of so-called dark factories, which are plants that are so heavily automated that they run with the lights out because there are no workers in them? It’s hard to think the author did not set out to misinform when the set-up gets within hailing distance of the dark factories concept, yet does not once invoke that phrase. From its top:

“Do you know what really impresses me? I saw a robot pick up an egg!’’ exclaimed Roger Smith, chairman of General Motors, in 1985. The American carmaker, which two decades earlier had been the first company to install a robotic arm, was then in the process of creating a “factory of the future” in Saginaw, Michigan. Smith envisaged a “lights-out” operation—no humans, only machines—that could help his company keep up with Japanese rivals. The result was shambolic. Witless robots couldn’t tell car models apart, and were unable to put bumpers on or paint properly. Costs ran wildly over budget. GM eventually shut down the factory.

Automation has come a long way since then. Yet Smith’s vision remains far ahead of reality at most factories. According to the International Federation of Robotics (IFR), an industry association, there were around 4.7m industrial robots operational worldwide as of 2024—just 177 for every 10,000 manufacturing workers. Having risen through the 2010s, annual installations surged amid the pandemic-era automation frenzy, but flattened off afterwards, with 542,000 installed in 2024.

Yes. sports fans, The Economist seriously is taking the position of the Development It Dares Not Name is on the horizon, as opposed to here. It doubles down on that message with the “Apocalypse soon” chart label plus the text:

That has been mirrored in the wider market for factory-automation equipment, including sensors, actuators and controllers, which has faced tepid demand over the past few years amid a slowdown in manufacturing, particularly in Europe….

Yet analysts see 2026 as an inflection point. The IFR reckons that annual robot installations will increase to 619,000 this year (see chart 2). Roland Berger, a consultancy, forecasts that inflation-adjusted growth in sales of industrial-automation equipment as a whole will rise from a meagre 1-2% in 2025 to 3-4% in 2026, then notch up 6-7% for the remainder of the decade….

With populations ageing, many manufacturers are struggling to find enough skilled operators to man their assembly lines, leading to rising demand for machines.

What is more, advances in industrial software are helping overcome many of the challenges that have previously hindered efforts to automate production.

It took me about a nanosecond on search to find a large, authoritative-looking study from Grandview Research, Dark Factories Market (2025 – 2030), that disputes this characterization, along with plenty of anecdata. First to the Grandview research:

The global dark factories market size was estimated at USD 119.19 billion in 2024 and is projected to grow at a CAGR of 8.7% from 2025 to 2030. This growth is primarily driven by the increasing adoption of industrial robotics and automated guided vehicles (AGVs), which enable continuous manufacturing with minimal human intervention. In addition, the expansion of the Industrial Internet of Things (IIoT) allows for real-time data monitoring and predictive maintenance, significantly improving operational efficiency.

The integration of AI and machine learning into manufacturing processes is further enhancing decision-making and self-optimization capabilities in dark factory environments. The demand for faster, more precise production in industries such as automotive, electronics, and pharmaceuticals is also driving the adoption of machine vision systems and additive manufacturing technologies. Furthermore, the global shift towards digital transformation and Industry 4.0 initiatives is accelerating the implementation of fully automated smart factories, fueling further growth in the dark factories industry

The growing adoption of industrial robotics in the dark factories enables continuous automated production with minimal human intervention. These robots enhance precision, speed, and consistency in manufacturing, helping companies reduce costs and improve efficiency. As demand for scalable and error-free production grows, industrial robotics continues to reshape the future of the dark factory industry.

In addition, the ongoing digital transformation is playing a key role in boosting industry growth, as businesses across industries are increasingly integrating advanced technologies such as IoT, AI, and cloud computing into their manufacturing ecosystems. This integration enables real-time monitoring, predictive analytics, and autonomous decision-making, helping manufacturers achieve greater efficiency, lower downtime, and improved product consistency, thereby boosting industry growth.

It also usefully identifies the main adopters:

And this sort of thing is anodyne compared to media stories and YouTube videos, showing that the idea that Chinese dark factories are set to eat the lunch of Western manufactures, has gotten ample attention, not just in the business press but aplenty in broader media. A few of many examples:

March 15, 2025 The Rise of ‘Dark Factories’: How AI-Driven Manufacturing Automation is Transforming Global Manufacturing From Algorithms to Altitudes: Mahendra Rathod’s Random Thoughts

April 16, 2025, The Rise of The Dark Factory: China’s Fully Autonomous Manufacturing Revolution Asia Lifestyle Magazine

May 1, 2025 XIAOMI’S REVOLUTIONARY NEW DARK FACTORY RUNS 247 WITHOUT BREAKS, LIGHTS OR PEOPLE Fanatical Futurist

July 22, 2025 What are China’s ‘dark factories’? Will America’s auto industry follow suit? What to know USA Today

September 4, 2025 Inside China’s “dark factories” where robots build EVs 24/7, threatening global automakers Electric Vehicles HQ

September 16, 2025 Will the US ever have fully automated ‘dark factories’? Manufacturing Dive

October 12, 2025 Western executives who visit China are coming back terrified Telegraph

The Telegraph story generated a lot of follow-on pieces with additional data and sightings, such as:

October 14, 2025 Western Executives Shaken After Visiting China Futurism

October 16, 2025 “Dark factories: The rise of robotic manufacturing in China” LinkedIn

This humble blog is well ahead of The Economist. Our stories focused on dark factories include:

April 30, 2025 China Leapfrogging the U.S. in Tech Innovation

November 23, 2025 Mission Impossible: Why the US Cannot Reverse Its Manufacturing Decline

which featured this YouTube:

A sampling from the many YouTube videos profiling dark factories:

The Rise of dark factories | Automation’s Bold Leap in Manufacturing (seven months ago)

China’s Dark Factories: So Automated, They Don’t Need Lights | WSJ (five months ago)

Inside China’s ‘dark factories’ where robots run the production lines • FRANCE 24 English (one month ago)

The Economist article centers on Siemens. Perhaps I missed something, but I have not seen the German heavyweight characterized as a leader in factory automation. But The Economist depicts Siemans as cutting edge:

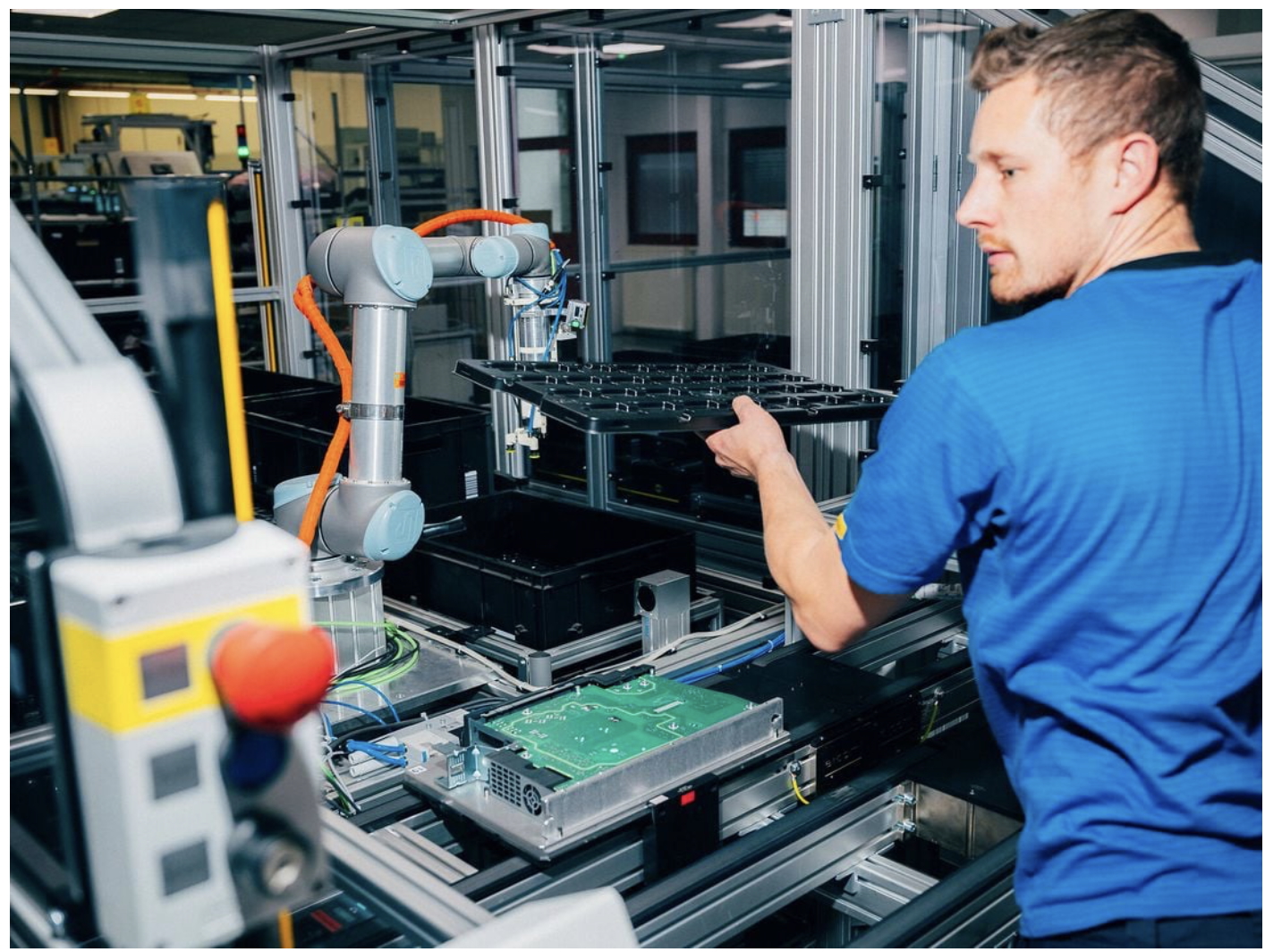

Hints of the future can already be glimpsed at the Bavarian factories of Siemens, itself a maker of automation equipment, in Amberg and Erlangen…..Robotic arms, many of them made by Universal Robots, whose parent company is Teradyne, an American business, do much more than pick up eggs. In glass enclosures they move swiftly about, welding, cutting, assembling and inspecting. Workers monitor and control production from computers attached to the machines.

The factory in Erlangen (pictured), which produces electronic components, is equally futuristic. Autonomous trolleys with screens attached zoom around the shop floor transporting goods between stations at which humans work side-by-side with robots. Others have lined themselves up neatly to charge.

The story includes photos of very brightly lit rooms, as well as ones with human operators:

Now admittedly, one might attempt a lame defense of The Economist by pointing out that even with less parts-intensive electric vehicles, China does not have a dark factory for cars yet. A couple of operations still use humans. They do for phones and I infer for pharmaceutical products. But many stories make clear that the many producers are making the overwhelming majority of these cars’ components on a dark factory basis. A January 2026 article in Automotive News Europe forecasts that cars will be made in fully dark factories by 2030.

But seriously, what excuse can The Economist possibly have for this embarrassment? Did Siemens plant a story and a newbie OxBridge grad who read German (in both senses of the word) wrote it up? Did an equity analyst pitch the contrarian idea that Europe might do well with AI implementation in factories and somehow manage to ignore the Chinese elephant in the room? Or perhaps did AI write this piece?

Regardless, it affirmatively misleads readers. If you subscribe to The Economist, you should cancel your subscription or demand your money back for this issue.

Fully agree that the Economist is an establishment rag, and with the main thrust of your article.

Just a word of caution – as a retired strategy consultant. There are a bunch of companies like GrandView Research, Markets & Markets, Technavio, that are essentially boiler-plate research shops based in India, that cover every industry under the sun (look at their industry menu). Their reports carry little primary research or industry expertise. I have had occasion to call their report authors with questions, and they knew very little technical specifics of the industry (and I wasn’t particularly technically deep in that industry, though had done some primary interviews).

I consumed a lot of industry research back in the day, but I don’t see the Grandview report as even remotely pretending to do primary research. It is a data compilation with trend extrapolation. That is useful. So I don’t understand your criticism.

And having also performed and consumed primary research oriented at trends and market growth, it is routinely wrong. Too many hypesters touting their services and wares. Primary research is still very valuable, for instance, for getting insight into customer thinking and economic drivers. And you usually have to pay real money for that sort of investigation. Admittedly, parts will often get out in analysts’ reports or the press.

And the bigger point is that The Economist didn’t do anything approaching the basics in generating this shoddy piece. Looking at a purely secondary assemblage of data of a Grandview type would have showed them that focusing their depiction of the factory revolution solely in terms of robotics, which is how they defined the market (even if they also hand waved about other technologies) was incomplete.

From experience they are very opaque on their data sources, and don’t really understand the different typologies within a specific industry. From reading their methodology blurb, they pull some published company stats and import/export data, and then make their own estimates. They never articulate a methodology for their market sizing. And every report you see, from every shop, has the same ToC – sizing by region and by product. The commentary is lame and not insightful – something they’ve pulled from some press reports I’d guess.

A firm like Gartner is more credible in tech – as they routinely gather actual sales data from industry players and interview them.

Anyway, just an aside, not to distract from your main point.

You are still talking past my point.

1. This is free and it has pulled together a fair bit of data.

2. It has a point of view as to how to define the industry. That is also useful as a forcing device.

3. All you can get from Gartner are teaser press releases that tell you less than the Grandview you keep whinging about provides: https://www.gartner.com/en/newsroom/press-releases/2023-05-03-gartner-identifies-top-five-smart-factory-implementation-risks-for-supply-chain-leaders

What Grandview did is useful to a reporter as a starting point and MUCH better than The Economist piece.

And as a former consultant, I have to tell you I had only one client that thought Gartner and Juniper research were worth paying for. It was valuable to me, but I was a total newbie to that industry. So incumbents may not see the price/value equation the way you do.

Perhaps you in Europe aren’t used to it.

But here in my part of the world, if you paid, the story appears.

After all, The Economist also needs to pay its bills…

The financial and the political ones.

“This humble blog is well ahead of The Economist.” On a number of topics, I should say. The one thing the The Economist consistently does uniquely well is its house style that conveys unwarranted confidence and superiority and I assume relates somehow to the tradition of English public schools. It’s been years since I read it regularly but I suspect that hasn’t changed.

FWIW, McKinsey emulates that writing style in its publications.

An oldie but goodie:

https://www.currentaffairs.org/news/2017/05/how-the-economist-thinks

The Economist is not a trusted publication but that has been true of the Economist for a long time. Had a thought while reading this post. From about the late 40s on, Japan – listening to the advice of people like W. Edwards Deming – went all in on quality to rebuild their country again and it worked. You wanted quality stuff, you went to Japan. It occurs to me that this is also a major aspect of dark factories and robots. They will push out quality products all day and all night long. Those countries that depend on manpower will not be able to compete long term as building quality goods is cheaper. So long term, you want quality products? You go to China now.

But is an all robot factory cheaper? It seems to me it would be quite expensive to implement. If you are turning out many copies of an expensive product like a car then the economics of it might make sense but less so for everyday items other than electronics like smartphones which require little assembly.

The simple answer to that is ‘it depends’.

The most efficient factories are not the most automated factories, they are the factories that get the blend of automation and human input right. The push for ‘dark factories’ in China makes little sense in China, a country where workers are still ‘relatively’ cheap and there is a huge youth unemployment problem. It is the result of economic policies that focus on subsidised capital (i.e. very low interest rates for investors) and grants for inputs.

There is nothing uniquely Chinese about this – I had personal experience of it as a student in Ireland in the 1980’s going on tours of factories. At the time, in an attempt to attract FDI and push up productivity, the government was giving massive tax incentives for capital investments – this applied to all industry, from textiles (a huge Fruit of the Loom factory) to medical device manufacture. For the most part, it proved extremely wasteful. I remember having been shown a room full of very expensive Apple Macs lying unused – from the point of view of the company, they hadn’t cost much, so nobody was all that bothered when they couldn’t find a use for them. As a bunch of poverty stricken students we did suggest that we could find a use for them, but they just laughed and changed the subject.

Some of those factories are still working away, many others proved to be white elephants. Once the government realised its mistake, the tax incentives were withdrawn and many companies ended up replacing machines with…. employees. This is far more common than you might think. Many car companies that enthusiastically embraced robots in the 1980’s and 90’s quietly withdrew them in subsequent years as it turned out people were better and cheaper. It happens all the time at a micro level – a friend in England worked in a company making high precision aluminium parts. They had some very expensive machinery that you could literally just load in alu billets at one end, and beautifully milled parts came out the other end. But the company ended up having to pay someone 24/7 to sit by the machines, as they found too often that even a tiny inputting error could result in someone arriving at the factory in the morning to find a small mountain of utterly useless (if gorgeous looking) machine parts all neatly piled up after the nights operations.

Another important factor is production flexibility. Robot factories require huge upfront developments, while human focused ones are more inherently flexible. You can make a robot redundant by switching off its power, but you still have to pay for it. So if you find that you can’t sell as much of the product as you’d planned over a long investment cycle, you are in big trouble. This, I think, is a key reason why China is finding it so very hard to solve the problem of overproduction. Companies simply don’t save much money by cutting production to match demand, so they just keep producing and praying that someone in the world will pay them something, anything, for what they are sending out.

“It depends” is right but it depends on how we define waste, subsidy, and efficiency, and those terms are doing far more ideological work here than is usually acknowledged.

What is described as “subsidized capital,” “white elephants,” or “waste” is often simply public investment under a fiat currency regime, evaluated using private-sector accounting standards that are inappropriate for a sovereign or quasi-sovereign state. A room full of unused Apple Macs may look like waste ex post, but ex ante it can also be a capability experiment – a way of building technical familiarity, supplier networks, and human capital. States that lead technologically are those that tolerate a high failure rate in public investment, because the payoff is not the individual asset but the national learning curve. By that standard, many “white elephants” are better understood as tuition fees.

Of course, the optimal blend of labour and machines is dynamic, not static. But that is precisely the point: if you never push the automation frontier because today’s labour is “cheap enough,” you guarantee that you will fall behind when conditions change. Productivity is not discovered; it is constructed through trial, error, and iteration. China’s push into robotics, sensing, and lights-out production is not about replacing workers today; it is about mastering the option set for tomorrow. Western firms that retreated from automation in the 1990s often did so because they were optimizing for short-term profitability, not long-term industrial competence and many of them are no longer around.

From an MMT perspective, the deeper confusion is the idea that bank-financed capital is inherently superior to state-supported or fiat-financed investment. For currency issuers (and even for constrained users like euro-area states, to a degree), the relevant constraint is not “cost” in financial terms but real resources, skills, and productive capacity. Paying interest to private banks to finance nationally strategic investment is not more “disciplined”; it is simply more lucrative for the financial sector. The West has largely forgotten that fiat money exists to mobilize real resources for public purpose, not to extract rents for the privilege of investment.

Ironically, the real inefficiency today is not China’s willingness to overbuild and experiment, but the West’s insistence that all investment must be justified as immediately profitable, privately financed, and risk-free to capital. That mindset produces exactly what we now see: hollowed-out manufacturing, brittle supply chains, and an inability to act at scale when circumstances change.

In short, yes – it depends. But it depends less on whether machines replace people, and more on whether societies still understand what money is for and the difference between public good and private.

Excellent comment!

It has been some time since I have read The Economist as well. Just wondering: are their articles still unsigned? It seems to be an attempt to present their writings as scripture rather than journalism. I recall John Ralston Saul’s description in The Doubter’s Companion (1994).

“A magazine which hides the names of the journalists who write its articles in order to create the illusion that they dispense disinterested truth rather than opinion.”

The Economist is to the City of London what Pravda used to be to the Soviet Union. As the UK is a country Thatcher thoroughly deindustrialized for the mirage of financialization, it’s not surprising their writers have glaring blind spots on the topic.

That said, Apple tried hard to robotize its (contracted) factories and had to beat a retreat. It turns out humans and their outstanding eye-hand coordination are hard to beat, and it’s not for lack of trying to:

https://www.theinformation.com/articles/what-apple-learned-from-automation-humans-are-better

Hmmm. Or they are justifying a fail to the shareholders.

And yet Xiaomi (and others) makes phones with better performance and features than Apple at half the cost in fully automated factories, phones that are banned from the US on “security reasons.”

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8YiaDXGQk7k

I visited China in 2010 as a guest at the opening of a factory producing laser components. What struck me was not simply the scale – though it was vast, reminiscent of the industrial districts of my own city multiplied many times over – but the structure. Firms were tightly clustered within local supply chains; logistics, finance, and planning were coordinated at the municipal level (in this case Nanjing), not dictated from a distant national capital. Local officials were expected to take risks and were given the authority and resources to do so. But accountability ran the other way as well: results were expected. This stands in stark contrast to much of the West, where local bureaucracies are incentivized to avoid risk entirely, substituting endless process and delay for performance, thereby ensuring that nothing fails and nothing truly succeeds.

The Economist’s framing also reflects a deeper conceptual error now common in Western discourse: the conflation of “AI” with large language models. China’s advantage is not that it is using machines to write reports or generate prose, but that it is deploying sensing, control systems, robotics, and machine vision across entire production ecosystems. This is AI as physical capability, not narrative simulation. By controlling the full manufacturing stack – from components to systems integration – China is compounding its lead, while much Western tech culture seems preoccupied with imagining an omniscient “god in a box” that talks impressively but touches little.

All of this raises an older and more serious question: if technology genuinely frees humans from toil and repetitive labour, what then is our purpose? There is nothing inherently dystopian about machines doing what machines do well. The danger lies in a social order that captures the gains for a narrow elite while leaving the rest dispossessed, anxious, and distracted.

That question becomes urgent in the context we now inhabit. We have already crossed 1.5°C of warming, and 2°C is likely within the next 15 years – well within the lifespan of today’s capital investments and political careers. Beyond that threshold, we are not talking about incremental change but systemic breakdown, economic as well as ecological. Faced with this reality, perhaps the most productive use of our technological prowess would not be to chase dominance in abstract power games, but to redirect human effort toward repairing what we are rapidly losing – our climate stability, our ecosystems, our shared “Garden of Eden.” Whether our institutions are capable of such a pivot is the real question the Economist – and all of us – should be asking.

I don´t know about “dark” factories. I wonder whether it is not a hype by people who don´t know the first thing about manufacturing. Unless they manufacture turbines or the like where you need a lot of dexterity there is hardly anybody anymore making things with their hands. The time when there were actual people working on conveyor belts is long gone. Because of huge capital costs all big factories run three shifts. You go to them at night and you will hardly see anybody. You might as well switch off the light. It is different during the day. Then the maintenance is done, the software reprogrammed or new tool machines aka “robots” installed. The need for these highly qualified workers is not decreased by these “robots”. On the contrary. You need even more of them and they need yet higher qualifications. And there in lies the great weakness of China. Their vocational education is abysmal whereas their academic education is excellent. But you need people who can do both if you want to run an automated factory. And by the way: whenever you hear that the pay is to high in the West and therefore manufacturing is shifting to the East: it is pure bull. First because wages are only a very small part of operating costs and second because highly qualified workers get as much in China now as in the West.

I honestly don´t see a qualitative shift in what I hear and read about Chinese factories.

Tell us about the vocational education in the west and especially in the Anglosphere…

What impresses me is the flexibility of Chinese manufacturing – Kevin Walmsey talks about a dark factory that can make RVs one week and mobile housing another week.* It starts with a joke – the factory of the future will have a man, a dog, and machines. The man’s job is to feed the machines, and the dog’s job is to bite the man if he touches the machines.

I have been looking at sourcing a gas and electrical slip ring for multiple gas and electrical channels. US quotes came in 15-20k, limited material and configuration options, no engineering support, and a 2-3 month timeline.

I will go with a Chinese manufacturer – costs under $1000, hundreds of potential options, strong engineering support, and shipping in a week. The timeline is the key factor for us, but we also do not have the 15k budget for our client.

There is a world of difference between a dark factory cranking out millions of identical cell phones (I saw such a factory in Japan 15 years ago – even if Apple still cannot make it work) – it’s a matter of QC on high-quality inputs and working out the automated manufacturing bugs – and dark flexible manufacturing.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8YiaDXGQk7k

Back in the wooly 00’s one of the firm principles I derived for myself was – the Economist is always wrong, and is always six months too late. One might argue over the precise amount of time, but somehow my black heart is gladdened to see that not much has changed with this particular publication.

That said, I do recall a London Review of Books article some years back going through the editorial changes at the Economist since its founding in the 1840s. I mean, it was always pushing a particular point of view, depending on the ownership and its preferences. Which, when the British Empire was a thing, were mostly aligned with the empire and the City of London; I suppose there must have been an inflection point towards “American” brand of neoliberalism at some point around the Reagan Era.

To wit, here is a Washington Post (!!!) critique from 1991 (!!!!!!!) – (http://www.theatlantic.com/science/archive/1991/10/-quot-the-economics-of-the-colonial-cringe-quot-about-the-economist-magazine-washington-post-1991/7415). An oldie, but a goodie. Though focusing rather more on style instead of the un-substance.

According to Alastair Crooke, this is also China using AI (industrial AI) for what AI is good at, rather than just trying to monetize and monopolize it as quickly as possible to become the next Bill Gates, a pioneer in this particular field (of monetizing and monopolizing) to benefit no one but himself..

I don’t think people understand the level of accuracy that robotics has.

I’ve seen numerous reports on “dark factories” makes about the most complex device there is to assemble, a smart phone.

Someone in China figured out it’s cheaper, more repeatable, less failures to do these factories than having humans.

The biggest take away to me is their incredible advancements in technology and manufacturing that the US doesn’t have.

And since when is building for an export market overproduction? The US builds planes for the world, is that over production? Or say cat selling bulldozers around the world, is that overcapacity? So Nvidea is also to be blasted for overproduction?

Add “our industrial prowess” vs “your pernicious overproduction” to the “Our Blessed Homeland” meme …

https://knowyourmeme.com/photos/2355607-our-blessed-homeland-their-barbarous-wastes

In a related note, China’s exports are relatively high-tech now. Last year, China’s trade surplus for mechanical and electrical exports was around $1.27 trillion, greater than its overall trade surplus of $1.19 trillion.

FoxConn installed netting and barriers in worker dormitories and factory buildings to prevent suicides. This is another cost saving advantage of robotic factories in China.

Excellent essay Yves. Anyone who invoked actuators, sensors, and controllers is speaking my language. Your point is exactly the right one: the world is awash in excess manufacturing bandwidth already, especially in China. Robots automate tasks and in all likelihood will just increase the production capacity of robotized industries. China is trying to fight ‘involution’, their term for deflationary price death spirals. The replacement of workers with robots will do nothing to help that. Plus it will render many millions of people surplus to plan. The CCP is not sentimental but it’s also not suicidal. This should be interesting.

The Economist Group isn’t really a news outlet, it’s a lead-generation machine for high-priced consultants. * They have systematically moved from reporting (journalism) to intelligence (data) to strategic advisory (consulting) and they’ve mastered the ‘Problem-Agitate-Solution’ model to a tee.

Step one: write a glossy feature on ‘Dark Factories’ or the ‘AI Revolution’ to trigger a sense of existential dread in mid-level executives and policy-makers.

Step two: wait for that FOMO to set in.

And step three: swoop in with consulting experts to sell ‘digital transformation’ potions along with a $50k set of PowerPoint instructions.

* In 2015, The Economist Group acquired Canback & Co (strategy consultants) and Signal Noise (data viz) to sell analytics to the C-suite, bolstered by industrial ties via Exor. In 2021, they launched Economist Impact and Economist Education, turning their editorial voice into a sales funnel for partnerships and executive training.

Actually “dark factories” implemented in CNC machine shops (so more like “dark machine shops”) with robots to load and unload the CNC machines have been a thing for quite a while now, and Fanuc, the Japanese CNC controller manufacturer, has been making CNC controllers and robots for this market for about twenty years now. Siemens is without doubt a leader in automation (one of the largest PLC and CNC controller manufacturers, but has never been big in robots although I have seem 840D CNC controllers used as robot controllers. Kuka was the big German robot manufacturer, and most of the engineering automation guys I worked with were shocked when Kuka was bought by the Chinese.