The New York Times has an odd story today, “Is a Lean Economy Turning Mean?” which discusses how conditions for workers have become dire. New jobs are scarce, and many of the ones out there don’t pay as well as what employees got in previous roles. Hello, downward mobility.

What makes the piece peculiar is that the Times seems to have woken up just now to the idea that the labor market has been difficult for the last few years. It’s been common for the media to follow the headline unemployment stats, when those are have considerable shortcomings. The self-employed (who may in practical terms may be severely underemployed) and part-timers are counted among the employed, but the most serious failing in the official unemployment release is the numerator, how unemployment is defined. As Walter Williams at Shadow Stats noted:

Up until the Clinton administration, a discouraged worker was one who was willing, able and ready to work but had given up looking because there were no jobs to be had. The Clinton administration dismissed to the non-reporting netherworld about five million discouraged workers who had been so categorized for more than a year. As of July 2004, the less-than-a-year discouraged workers total 504,000. Adding in the netherworld takes the unemployment rate up to about 12.5%.

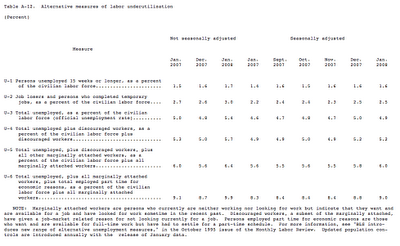

I have not gone trolling for an updated estimate of how large the pool of discouraged workers is, but table in the Bureau of Labor Statistics Household Survey, “Alternative measures of labor underutilization” sheds some light (click for larger image),

It shows raw underutilization of 9.9% and seasonally adjusted underutliization of 9/0% as of January 2008. That seems more consistent with the lack of labor bargaining power in the economy:

The Times indirectly acknowledges the limitations of the unemployment stats by looking at labor utilization and finding a downtrend there.

But the bigger question is: why hasn’t this gotten more notice sooner? It’s widely acknowledged that inflation adjusted wages have been stagnant since the 1970s. And even in a nominally robust economy like New York City, the white collar cohort not working on Wall Street has been squeezed. Everyone I know in a firm or corporation is doing 50% more than they were expected to do a decade ago, and they certainly aren’t earning 50% more in real terms or even nominal terms. (And the 50% is not an exaggeration: I know quite a few people who are single-handedly doing what was formerly two jobs at their company). Plus we have a culture where many white collar workers are expected to be on call virtually all the time, which both extends the number of hours worked and adds to stress. Yet few have wanted to see these developments as a sign of the falling standing of workers.

From Peter Goodman of the New York Times:

Nicole Flennaugh has a college degree, office experience and the modest expectation that, somewhere in this city on the eastern lip of San Francisco Bay, someone will want to hire her.

But Ms. Flennaugh, 36, a widow, cannot secure steady, decent-paying work to support herself and her two daughter…

“You’re used to making $17 an hour with benefits, and now you have to take any job for $8 an hour,” Ms. Flennaugh says….

“I’ve literally sat and cried, but my friends with double degrees are doing worse,” she says. “It’s the economy. It’s really bad.”

Now, it’s getting tougher — particularly for those at the lower rungs of the economic ladder, and especially for African-Americans like Ms. Flennaugh…..

Many companies, long reluctant to add workers, are hunkered down and waiting for improved prospects, engaged in what Ed McKelvey, a senior economist at Goldman Sachs, calls “a hiring strike.” Americans with jobs are taking cuts to their work hours; those without jobs are staying out of work longer, or accepting positions that pay far less than they earned previously.

Teenagers are struggling to land minimum-wage jobs at fast-food restaurants, because those positions are increasingly being filled by adults. And those with poor credit are finding that this can disqualify them from getting a job…

Indeed, the increasingly anemic job market comes on the heels of six years of economic expansion that delivered robust corporate profits but scant job growth. The last recession, in 2001, was followed by a so-called jobless recovery. As the economy resumed growing, payrolls continued to shrink.

Even as job growth accelerated in 2005 and 2006 before slowing last year, it was not enough to return the country to its previous level. Some 62.8 percent of all Americans age 16 and older were employed at the end of last year, down from the peak of 64.6 percent in early 2000, according to the Labor Department.

“The economy never got its groove back after the tech bubble burst,” says Mark Zandi, chief economist at Moody’s Economy.com. “We’re still feeling fallout from the collapse of the tech economy and the accounting scandals. There are still psychological scars for the managers affected. Managers are less interested in taking risks.”….

Oakland, long known as the blue-collar sibling to the aristocratic San Francisco across the bay, is among the metropolitan areas that never fully recovered from the last recession, with fewer jobs today than in March 2001, according to Economy.com….

Home to about 400,000 people, Oakland is enormously diverse, with blacks making up 36 percent of the population, Hispanics 22 percent and Asian-Americans 15 percent, according to the 2000 census. The city is racked by stubborn poverty, with one-fifth of all households living on less than $15,000 in annual income, according to the census.

Given that picture, Oakland reflects a national trend: The weaker labor market is especially pronounced for African-Americans, and black women in particular, a slide that has halted a quarter-century of steady gains.

From 1975 to early 2000, the percentage of African-American women who were employed jumped to 59 percent from 42 percent. Two years later, following a recession, the percentage had dropped to 55 percent. Since then, employment among African-American women has shown little change, reaching 55.7 percent at the end of 2007.

In a recent paper, the Center for Economic and Policy Research asserted that a recession in 2008 would be likely to swell the ranks of the unemployed by 3.2 million to 5.8 million, while raising the unemployment rate among black Americans to 11.3 percent to 15.5 percent, compared with 8.3 percent in 2007.

Nationally, the unemployment rate remains at a historically low level of 4.9 percent, though this does not include people who have given up looking for work.

The slide in employment is occurring at a time when jobs are more important than ever for millions of households headed by African-American women, because welfare changes in the 1990s forced many into the job market to compensate for a loss of public assistance.

“The labor market for low-income women is so poor that it’s almost a hoax,” says Randy Albelda, an economist at the University of Massachusetts in Boston.

For more than a decade, Dorothy Thomas, 49, an African-American and a mother of two, worked as an administrative assistant at various health care centers in Northern California. In her last job, she earned $16 an hour, as well as benefits, she said.

It was never enough to pay all the bills, she said, so she made choices, paying this one, not paying that one, all the while focused on one mission: getting her two daughters through school. She lived in apartments in better neighborhoods, paying more rent than she could afford to ensure that her girls attended better schools.

“I truly bought into the idea that education is the way out of poverty,” Ms. Thomas says. One daughter received a master’s degree in education and is a teacher in Hawaii, she says, and the other is still in college.

But the bills for Ms. Thomas are still coming due. She lost her car in November 2005 after she fell behind on the payments. Unable to drive to work, she lost her job. Since then, she has been unable to find a job.

Several times, she has landed interviews that seemed likely to bring offers, but the jobs required a credit check — a test she cannot pass.

“My credit is just so in shambles,” she told a classroom full of people gathered for a credit counseling session at the Private Industry Council. “More and more jobs are checking your credit. They’re saying that credit is a reflection of your character.”

Ms. Thomas deftly toggles between different modes of speech, from street-smart to receptionist-smooth. But getting to work without transportation and buying clothes for interviews without cash are beyond her abilities….

Government data show that the labor market has weakened in recent years for nearly every demographic group…The source of this weakening and what it says about the overall, long-term health of the economy are the subject of fractious debate.

Some economists argue that the labor market has merely settled back to earth after years of ridiculously aggressive investment in technology, which created far more jobs in the 1990s than could be sustained.

“This is a return to normal,” says Robert E. Hall, an economist and senior fellow at the Hoover Institution, a conservative research group at Stanford.

But others conclude that the sluggish job market reflects long-term, systemic forces reshaping the American economy. It represents, they say, the underbelly of the so-called new moderation that has made recessions less frequent and less severe.

Traditionally, the American economy has often expanded in extreme cycles. In periods of growth, companies hire aggressively. When they sense a slowdown, they cut back, laying off workers and curtailing investments, amplifying the ripples of retrenchment. Now, however, companies aim to keep their work forces lean all the time….

In 1994, 30 million people were hired into new and existing private-sector jobs, according to the Labor Department. By 2000, the number of hires had expanded to 34 million. A year later, in the midst of the recession, hiring slackened to 31.6 million, while layoffs winnowed the work force.

In 2003, with the economy again growing, layoffs slowed, but the private sector hired only 29.8 million — a figure that has nudged up only a little in the years since.

Rather than hire and risk having to fire in another downturn, companies added hours for those already on the payroll and relied more on temporary workers, said Mr. McKelvey, the Goldman Sachs economist. Manufacturing companies continued to automate, to squeeze more production out of the same number of workers, while shifting jobs to lower-cost countries like China and Mexico. For lower-skilled workers, that intensifies the competition for the jobs that remain.

“Now, you’re not only competing against the guy next door,” Mr. McKelvey says. “You’re competing against the guy across the water.”

Some economists say the weakness of hiring in recent years may protect those with jobs against the usual impact of a recession: Many companies are so lean that the unemployment rate may not increase much.

“It’s not your grandfather’s recession anymore,” says Jared Bernstein, senior economist at the Economic Policy Institute, a labor-oriented research group in Washington. “You’re probably going to see fewer layoffs, because you just don’t have the traditional model.”

But the same trend suggests that the impacts of the slowdown are likely to be felt deeply for several years, even after the economy resumes a swift expansion, Mr. Bernstein added.

Before 1990, it took an average of 21 months for the economy to add back the jobs shed during a recession, according to an analysis by the Economic Policy Institute and the National Employment Law Project, a worker advocacy group. Yet in the last two recessions, in 1990 and 2001, it took 31 months and 46 months, respectively, for employment levels to recover fully.

In the recessions of the early 1980s and the early 1990s, the ranks of the so-called long-term unemployed — those out of work for 27 weeks or more — jumped to well above 20 percent of all unemployed people. But in both cases, that share eventually settled back to close to 10 percent of the unemployed.

After the 2001 recession, however, the long-term share stayed above 20 percent from the fall of 2002 until the spring of 2005. In the months since, it has never dipped below 16 percent. In January, 18 percent of those unemployed had been without work for at least 27 weeks, according to the Labor Department.

Re: Employment Troubles,

I I find it relaxing to read Henry

THE ROAD TO HYPERINFLATION

Fed helpless in its own crisis

By Henry C K Liu

As economist Hyman Minsky (1919-1996) observed insightfully, money is created whenever credit is issued. The corollary is that money is destroyed when debts are not paid back. That is why home mortgage defaults create liquidity crises. This simple insight demolishes the myth that the central bank is the sole controller of a nation’s money supply.

Greenspan sees no Fed cure

Alan Greenspan, the former Fed chairman, wrote in a defensive article in the December 12, 2007 edition of the Wall Street Journal: “In theory, central banks can expand their balance sheets without limit. In practice, they are constrained by the potential inflationary impact of their actions. The ability of central banks and their governments to join with the International Monetary Fund in broad-based currency stabilization is arguably long since gone. More generally, global forces, combined with lower international trade barriers, have diminished the scope of national governments to affect the paths of their economies.”

In exoteric language, Greenspan is saying that short of moving towards hyperinflation, central banks have no cure for a collapsed debt bubble.

Greenspan then gives his prognosis: “The current credit crisis will come to an end when the overhang of inventories of newly built homes is largely liquidated and home price deflation comes to an end … Very large losses will, no doubt, be taken as a consequence of the crisis. But after a period of protracted adjustment, the US economy, and the global economy more generally, will be able to get back to business.”

Greenspan blames “the Third World, especially China” for the so-called global savings glut, with an obscene attitude of the free-spending rich who borrowed from the helpless poor scolding the poor for being too conservative with money.

Yet Bank for International Settlements (BIS) data show exchange-traded derivatives growing 27% to a record $681 trillion in third quarter 2007, the biggest increase in three years. Compared this astronomical expansion of virtual money with China’s foreign exchange reserve of $1.4 trillion, it gives a new meaning to the term “blaming the tail for wagging the dog”. The notional value of outstanding over-the-counter (OTC) derivative between counterparties not traded on exchanges was $516 trillion in June, 2007, with a gross market value of over $11 trillion, which half of the total was in interest rate swaps. China was hardly a factor in the global credit market, where massive amount of virtual money has been created by computerized trades.

Credit score as a reflection of a worker’s character??? This, when real wages stagnate while the cost of living just won’t stop going north?

Excuse me if I am more than a little skeptic. IMO, this is just another way to put a criteria on the table to filter candidates in a apparently “objective” manner. “Look ‘Ma! I’ve got a number to justify my decision.”

““This is a return to normal,” says Robert E. Hall, an economist and senior fellow at the Hoover Institution, a conservative research group at Stanford.”

A return to normal? Ooooh! So, a job growth that can’t even absorb the natural increase in active population is the norm now? With stingy unemployment benefits, no real training program for displaced workers, no welfare program that can be called decent, now we learn that it just too bad Buster but you can expect to have fewer and fewer opportunities to work because we are experiencing a “return to normal”. That is reassuring indeed.

Conservatives have had a chance to prove their economic thesis since 1980 and the result isn’t pretty for workers. Something will burst in an ugly way (social unrest cannot be discarded) if a big number of layoffs happen during this recession.

It is becoming more and more difficult for middle income workers to feel increasing job insecurity and financial anxiety, while a selected few are raking in enormous amounts of bonuses, severance packages and paychecks. Regardless of WHY it is so, people may reach a “I’ve had it!” point and come to rebel against this situation.

Instead of obfuscating the numbers and spinning reality, our political leaders should take a hard look at the situation now, before a social crisis erupt.

Yves said the following:

“Everyone I know in a firm or corporation is doing 50% more than they were expected to do a decade ago, and they certainly aren’t earning 50% more in real terms or even nominal terms. (And the 50% is not an exaggeration: I know quite a few people who are single-handedly doing what was formerly two jobs at their company).”

I don’t have reason to question the accuracy of that statement.

But it raises a very important question:

How do we statistically measure this for society as a whole?

It would appear that this is not being captured at all in the statistics currently being compiled.

Yet this is a critical variable that needs to be objectively measured if we are to have any remotely accurate idea of the true level of “quality of life” in the nation.

It implies that America is currently flying blind in terms of measuring the true quality of life (not to mention having highly inaccurate measurements of true unemployment).

It also brings up a larger question of compiling more accurate data that measures the “overall quality of life”.

How do you measure the quality of human relationships (trust, social cohesion, love, friendship)?

How do you measure the quality of the work activities that people perform every day (is the work stimulating or fulfilling)?

How do you measure the quality of the physical living environment (climate/architecture/etc) that people live in every day?

These three things are what really count, what really determine each person’s happiness.

The current statistics seem to paint a totally false picture of what the quality of life in America really is.

The nation is worshipping at the altar of a false god—the god of production/consumption. This is otherwise known as the “American Dream”. The idea that “consumption = happiness”. Let us thank Madison Avenue for decades of brainwashing on television since World War II for this present state of affairs.

Yes, I watched the BBC documentary “Century of the Self”. I would strongly recommend reading the book “The Status Seekers” written by Vance Packard.

One of the things that will give you bad credit is being unemployed. Why would an employer use this to screen applicants? I don’t get this.

How do you discuss the low end of the job market in Oakland without discussing immigration? 37% of the people living in CA were born outside the country. To pick one example, employement growth in construction has been dominated by recent immigrants. Do illegals working as independent contractors with an ITIN instead of an SSN show up in unemployement statistics?

blueskies