Oil prices continue their seemingly relentless march upwards, breaching the $143 a barrel level Tuesday. Even the headlines are selling the bull’s case. Note that a Bloomberg’s story was titled, “Crude Oil Rises a Second Day as IEA Predicts `Tight’ Supplies Through 2013.” Yet what did the text say?

The IEA said in a report that spare OPEC capacity will shrink by 2013, keeping the market “tight.” The growth in global excess supply will peak at about 2.5 million barrels a day in 2010, dropping to less than a million a day for the next three years, the agency said.

Note the IEA sees the supply/demand situation improving through 2010, then tightening as the emerging market demand picks up in a strengthening global economy. Yet oil, unlike copper or gold, is not an easily stored commodity. Thus, there isn’t a reason to expect market participants to bid it up now in anticipation of conditions in 2012. Indeed, even if storage were not problematic, given the cost of money and the improving supply/demand conditions near-term, were hoarding practical, you’d expect to see it later, and thus reflected in spot prices a year or two hence (note we have discussed before that oil is actually not a very storable commodity).

Admittedly, I haven’t seen the entire report (it’s $500, sports fans), but the forecasts for 2010 and beyond seem unduly precise given the uncertainty of production out of Iraq. Iraq is underdeveloped, and claims to have new proven reserves based on recent surveys which would give bigger reserves than Saudi Arabia. Admittedly, even if these assertions prove out, there is still a good deal of uncertainly as to when supply would come on line. But this would appear to be a wild card that is not acknowledged in the IEA estimates.

Prices should in theory reflect near-term conditions, longer-dated futures should reflect intermediate-term ones. But the news reports picked up on the gloomy tone of the IEA report (and we must note that the IEA has consistently hewn to conventional wisdom, having given cheery assurances about the future prospects for oil supplies until prices started to run up) and that in turn was incorporated in prices.

Note that this forecast contradicts the predictions of the market’s darling analyst, Goldman, which predicts after a “super spike” this year to perhaps $200 a barrel, oil will fall to $75 a barrel in 2012 normalized.

Why are we taking such a skeptical posture? Because there isn’t enough skepticism around. We accept that oil is a finite resource and that all things considered, higher prices are a good thing because the will encourage conservation, a transition to other energy sources, and serves as a de facto carbon tax. But a 50% price increase in five months is not solely due to supply and demand factors. This is a two sigma move in the absence of war or other sufficient explanation.

In fact, this may simply be animal spirits, aka bull market psychology. Per the IEA report, the press and even analysts are validating the prevailing perceptions. This tendency is turn is supporting selective readings of the facts (it’s a well demonstrated cognitive bias that when an even-handed documentary is shown to people who have pro and con views on the material under discussion, each side will focus on the information that favors its views and discount the rest of the presentation).

Let’s turn to some sightings du jour. On the one side, we have Goldman via Reuters in “Tight credit driving shorts out of oil market“:

Tighter credit conditions are forcing leveraged speculators and oil producers with weak credit to close out short positions in crude oil futures, Goldman Sachs said in a research note Tuesday.

Open interest in New York Mercantile Exchange light sweet crude oil futures CLc1 has been declining since the third quarter of 2007, a phenomenon Goldman says is likely due to the credit squeeze that began to grip global markets at that time.

“The short side of the market has a greater need to cover in response to deleveraging and decreasing credit terms,” wrote a Goldman team led by Giovanni Serio and Jeffery Currie.

Open interest in the NYMEX light sweet crude contract fell to a 15-month low last week at 1.3 million contracts, according to Reuters EcoWin.

The credit crunch may be further skewing the oil market toward the upside by preventing some cash-strapped long players from liquidating positions as many are likely using substantial gains in oil as collateral for other investments, Goldman said.

Note this discussion does not reflect supply and demand conditions. Note also open interest could well have moved to the ICE or OTC in the light of regulatory scrutiny in the US.

Now from Marc Faber via Bloomberg (and note Faber was bullish on commodities as recently as a few months ago):

Demand for industrial commodities including oil will fall, pressuring prices, because the financial sector is in “disarray” and the U.S. economy will continue to slump, investor Marc Faber said.

“The industrial-commodity complex is vulnerable because demand will slow down,” said Faber, publisher of investment newsletter the Gloom, Boom and Doom Report. “The economy is weakening, corporate profits will disappoint, valuations are not particularly attractive, and the financial sector that serves to channel savings into investment is in disarray.”

Demand for commodities will fall after raw materials including oil, corn, copper and gold touched record highs in the first half, Faber said in an interview on Bloomberg Television. The global economic slowdown will last a “very long time,” he said.

“The financial crisis has been the appetizer,” Faber said, referring to the $400 billion in writedowns at the world’s largest banks and securities firms in the past year. “We still need the main dish.”…

The U.S. economy went into recession last October and current statistics are hiding the “severity” of the recession, Faber said. Economists have also understated the rate of inflation as higher food and energy costs impact consumers, he said.

Commodities will face a “correction” after a seven-year rally and prices will decline in the next six months to one year, Faber said on June 26. Faber told investors to abandon U.S. stocks a week before 1987’s so-called Black Monday crash.

Faber did caution that all bets on oil are off if Iran is attacked.

Keep in mind that these views are not necessarily incompatible. We could still see further price appreciation before the recognition of demand destruction takes hold.

But wait a second. We have evidence of demand destruction now. We’ve already mentioned, as have others, the fall in miles driven in the US, a 20% drop in petrol sales in the UK, and 14% on the Continent.

Last week, Ed Wallace at BusinessWeek compiled some recent sightings:

“[U.S.] demand for oil over the first five months of the year was off 2.5%* from last year.” —American Petroleum Institute, June 18, 2008, Associated Press Online (*Translation: We are using approximately 525,000 fewer barrels of oil per day.)

“Iran has 15 [oil] supertankers idling in the Persian Gulf capable of storing more than 30 million barrels of crude.” —Bloomberg, June 16, 2008

“Thunder Horse started pumping from a single well on Saturday…and on schedule to have the field online by yearend. Thunder Horse alone will increase overall U.S. oil and gas production by 3.6%. Add British Petroleum’s Atlantis platform that started up last year, and the boost grows to 6.4%.” —Houston Chronicle, June 16, 2008

“Asian refiners cut West African crude oil imports in June. Asian imports will fall 36%* to 830,000 barrels a day this month from May’s 1.3 million barrels per day.” —Bloomberg, June 17, 2008 (*Translation: Another 470,000 barrels a day of mostly light sweet crude rejected by the market.)

“Refiners across Asia said on Monday they were not likely to buy more Saudi crude at current prices, highlighting the kingdom’s challenge in attempting to contain soaring markets by promising extra barrels. The world’s top exporter is set to increase output to 9.7 million barrels per day in July. The extra 200,000 bpd, if confirmed, would come on top of the 300,000 bpd it promised to pump this month.” —Livemint (part of the Wall Street Journal Digital Network), June 16, 2008 (That’s another 500,000 barrels of oil apparently not purchased.)

“Daily shipments of North Sea Brent crude…will rise 8.6% in July. Tankers are set to load 175,097 barrels a day of Brent crude next month, up from 161,300 barrels a day scheduled for June.” —Bloomberg June 9, 2008

“‘[U.S.] Drivers Cut Back by 30 Billion Miles:’ Americans drove 22 billion fewer miles from November through April than during the same period in 2006-07, the biggest such drop since the Iranian revolution led to gasoline supply shortages in 1979-1980.” —USA Today, June 22, 2008

“South Korea’s May Oil Consumption Falls on High Price” —Bloomberg, June 20, 2008

“Faced with increasingly severe fuel shortages and the prospect of power failures during the summer air conditioning season, the Chinese government unexpectedly announced a sharp increase* late Thursday night in regulated prices for gasoline, diesel, and electricity.” —The New York Times, June 20, 2008 (*Translation: Gasoline and diesel prices in China increased by 18% immediately to cool demand.)

Now, just for fun, let’s add up all of the excess oil on the market, resulting either from cutbacks in demand, as in the U.S., Asia, or Korea, or from surplus production from oil producers such as Saudi Arabia and in the Gulf of Mexico. Just in the articles I cited, it comes to 1,989,000 barrels of oil a day. That does not include the upcoming Saudi Khursaniyah field that will open in August with another 500,000 barrels per day in production. Some shortage, huh?

And that’s just one week of articles. And, to be fair to the oil market and the spirit of this column, the world did lose some production out of Mexico, more out of Nigeria; Russian production is down slightly; and the Thunder Horse platform in the Gulf of Mexico, three years late thanks to hurricanes, is not fully operational as of this writing. But, then again, the surplus 1,989,000 barrels of oil per day we counted did not include what’s potentially in those 15 oil supertankers leased by Iran and parked in the Persian Gulf. Now is also a good time to note that on June 20, Saudi Arabia announced that its Khurais oil field would be online by this time next year, and that would contribute another 1.2 million barrels of oil per day to the world market.

Now this is admittedly a dog’s breakfast of tidbits. The Iranian crude is floating around due to limited refinery capacity for their heavy crude. Ditto Saudi Arabia, whose “sour” crude currently offer is less prized than sweet crude. But the IEA similarly encourages an unduly superficial discussion of the oil situation by glossing over the fact that to the extent there is a supply/demand issue, it’s in the light grades of crude, and the comparative abundance of sour crude is in part due to insufficient refinery capacity for those grades.

Oh, and there is perilous little mention of the fact that the particularly heavy crudes that Venezuela and Iran have in abundance are economical only when prevailing oil prices are high.

A more pointed and sophisticated discussion of the issues raised by Wallace comes from “Massive Drop in US Demand in April” from the blog Peak Oil Debunked (hat tip reader Michael):

On Monday (6/30), the EIA reported a gigantic drop in U.S. oil demand. And the figures are for April — way back in the good ol’ days when crude prices ranged between $110-$120.

EIA revises down U.S. April oil demand by 4.2 pct

WASHINGTON, June 30 (Reuters) – U.S. oil demand in April was 863,000 barrels per day less than previously estimated and down 811,000 bpd from a year earlier, putting petroleum consumption at the lowest level for any April month in six years, the Energy Information Administration said on Monday.

The lower oil demand was due to rising fuel prices and a faltering U.S. economy that has cut into petroleum use.

U.S. oil demand in April was revised down 4.2 percent from the EIA’s early estimate of 20.631 million bpd to the agency’s final demand number of 19.768 million bpd, and was 3.9 percent less from 20.579 million bpd a year earlier.The final numbers were included in the EIA’s monthly petroleum supply report and are always different than the initial estimates in the agency’s weekly petroleum report.Source

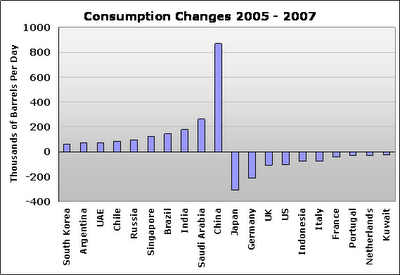

The size of this drop (down 811,000bpd, year-on-year) is massive. Indeed it’s almost enough to wipe out total worldwide growth in oil consumption from 2006 to 2007 (990,000bpd, according to the BP Statistical Review 2008). It is enough to wipe out two years worth of consumption growth from China:

Furthermore, Chinese demand can’t be fingered for price rises in April because Chinese imports were down year-on-year, as I noted earlier:

A decline in China’s oil imports in April, the first year-on-year drop in 18 months, also raised questions over demand. China is the world’s second-largest oil consumer after the United States. […] China’s April crude oil imports fell by 3.9 percent from a year ago to 3.47 million bpd, and were also down from the record of 4.07 million bpd in March, official Chinese data showed.Source

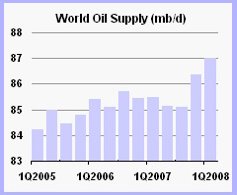

There’s been no serious decline in supply. We’re on the same old plateau, and in fact the IEA reports that supply was up considerably in the 1Q 2008:

Put it all together, and the “supply outstripping demand” theory of the feverish price action since March is emanating an extremely fish-like odor. U.S. demand down by a whopping 0.8mbd year-on-year. That’s the elephant in the room now.

Nice job on the detective work. Glad you mentioned that speculators could go elsewhere.

A oil country like Saudi Arabia with its portion sales of lets say, 12 billion collected daily could, if they wanted to, speculate on oil price or maybe even some US banks might have the cash to speculate. If 80% of the oil trading in done in the US and through ICE then what is the other 20% up to?

Yves, good stuff as always. Reading about oil prices is so much fun when one doesn’t have a skin in the game. I mean, I am seriously impressed with those who have the testicular fortitude to trade this thing, especially on the short side.

I always preferred smooth, reasonable markets to super volatile ones. The trend is up, up, up. One day, of course, that’s gonna change. Bubbles burst as sure as the sun rises. But timing is everything!

Moin Yves,

i´m a long time reader and want to thank you from Germany for your blog and especially for this post!

Spend a moment and think about Goldman’s prediction. They’re saying oil will rise to $200 and then fall to $75. When you think about why they would make such an odd prediction, it has to be one of 3 possible conclusions:

1. Goldman analysts are fools

2. Goldman is shorting oil and playing us for fools, or

3. Goldman thinks there will be an Israeli nuclear strike on Iran before year end.

While it could be 2, I’m going with 3. Where there’s smoke, there’s fire and there is a LOT of suspicious smoke in Israel.

I suspect that most of the big players (ie Goldman, etc) in oil are holding until the election which is why you’re seeing demand destruction but not price capitulation…

Yves: Note the IEA sees the supply/demand situation improving through 2010, then tightening as the emerging market demand picks up in a strengthening global economy. Yet oil, unlike copper or gold, is not an easily stored commodity. Thus, there isn’t a reason to expect market participants to bid it up now in anticipation of conditions in 2012.

Martin Feldstein makes the point in yesterday’s WSJ that producers would definitely leave oil in the ground if they believe the future price is above the present price plus whatever return they could expect from investing the proceeds of selling it now.

In other words, it’s not buyers bidding up the price, it’s producers restricting supply. And unpumped oil is very easily stored by simply not pumping it.

This, to me, is the best explanation of what’s happening.

But I believe the producers have misread the mid-to-long term effects of the increase of the past year, and they may not be ready for the whip-saw.

One interesting historical point, I was reading Napier’s “Anatomy of the Bear” last night and he shows that in from 1920 to 1921 commodities crashed ca. 40-50%. But they were still above 1914 prices.

In otherwords, even if this is just a pause in a long-term commodity bull market, the short-term swing could be dramatic.

A lot of the arguments you cite, and especially the one from Peak Oil Debunked, strike me as sophistry. The numbers just don’t add up.

There is something in physics called mass balance or material balance. You can read about it here…

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mass_balance

but essentially it is based on the principle that matter cannot disappear or be created spontaneously.

In the immediate case it would look something like this:

I(april)=I(march)+P(april)-C(april)

where:

I(april) = Inventory at end of april

I(march) = Inventory at end of march

P(april) = Production during month of april

C(april) = Consumption during month of april

In the case of oil, inventory fluctuates very little. This is so because increased inventory requires increased storage, and, relatively speaking, oil storage is almost non-existent. Therefore,

I(march) = I(april)

is for all intents and purposes a true statement.

Plugging this back into our material balance equation, we can solve for the following result:

P(april) = C(april)

The mental picture that Peak Oil Dubunked paints is that world oil production is up 2 million BOPD and consumption is flat or falling. But how can this be? Where is the oil? We’re talking (2 million BOPD)x(91 days) or 182 million barrels of oil for a single quarter. Even if Iran does have 30 million barrels sitting in tankers in the Persian Gulf, where’s the other 150 million barrels?

All this carries us back to what Paul Krugman has been saying for months. It’s why the oil traders hang on pins and needles every Wednesday morning waiting for the inventory numbers. Everything is contained in the inventory numbers, and anything else is just pure sophistry.

Glad you are giving Marc Faber a little column space. His predictions have been very good overall. When Marc says commodities are too high we’d better listen up because he has been the commodity cheerleader for years.

There is a critical factor you are leaving out.

I can’t at the moment find a reference but my memory is that production from currently active oil wells is declining by 4 million bpd.

That means that new wells coming online have to make up that difference AND allow for growth from chindia, etc.

The drop in gas consumption is trivial by comparision.

The FinancialTimes story on the IEA report can be found here…

http://www.ft.com/cms/s/0/cd683aa0-4764-11dd-93ca-000077b07658.html

IEA is predicting annual non-OPEC supply growth of .5 per cent over the next five years against global demand growth of 1.6 per cent. OPEC will have to close the gap. Since OPEC currently produces only about 40% of the world’s oil, this means that OPEC production will need to grow by almost 3% per year over the next five years.

But this may pose some problems. As FT observed: “The IEA said it believed Saudi Arabia was having bigger problems than the kingdom, the world’s largest exporter, was willing to admit to…”

All this of course plays out on a back drop of very little spare oil producing capability. Any disruption of oil supplies for any reason–hurricane, war, etc.–could send oil prices soaring.

That said, IEA’s crystal ball hasn’t worked too terribly well in the past, so I don’t see why anyone would put much stock in its current predictions.

Being the cynical old pessimist that I am, I don’t think we can rule out Marc Farber’s prognosis. A severe world-wide recession might certainly destroy enough demand to bring prices down. Back in the 1980’s–a time of recession and high oil prices–world consumption dropped from 67 to 58 million BOPD (1979-1983). Simultaneously, non-OPEC production rose from 35.5 to 39.4 million BOPD. Could it happen this way again? Who knows, but it would be foolish to rule out the possibility. Farber isn’t the only person making such bearish predictions, and, as someone said in regards to the housing bust, if we want to protect outselves we have to “imagine the unimaginable.”

I have been surprised to not see any detailed analysis anywhere of potential effects on the global economy, currencies, etc were oil prices to dramatically reverse (other than brief mentions of likely increased margins for producers of goods) especially given how large a percentage of the US current account deficit oil is now responsible for.

However, thanks to gaius marius’s blog, I just found this, and it provides some observations on possible monetary effects:

http://www.investorsinsight.com/blogs/john_mauldins_outside_the_box/archive/2008/06/30/the-end-of-the-inflation-scare.aspx

DownSouth,

I guess _all_ above ground storage would have to be taken into account and I’d also guess that it is not.

Correct me if I misread but it seems you are arguing the impossibility of overproduction (even though such has happened in the past). S/D is not an immediate identity other than in (some) theory; there are lags.

So far as the changing balances, you might find this June report from TD Bank Financial Group of interest. (Link is on right hand side)

With All The Talk About Peak Global Oil Supply, What About Peak Oil Demand?

http://www.td.com/economics/qef/qefjun08.jsp

Emphasis on S/D, though, misses the point which has to do with, imo, extreme disconnect between the real and the financial, the latter having become the maker of benchmarks. Price formation has been turned upside down and not just over the last one or two years.

Following up on the prior comments – is it possible that the production figures are flat out wrong? If not OPEC, then perhaps US producers are “hoarding” oil in the ground

hbl,

Right you are, a steep decline in price of oils might well affect not only exporting nations’ surpluses but, without interest rate adjustments, their willingness to recycle petrodollars.

Then there are who knows what notional amount of structured products built on crude oil futures and options.

Poking around, I noticed a two-year-ago Futures Industry Mag. article – a clip:

Another important driver for growth in the

futures unit is the growth of the commodity

structured note business. Although this is pri-

marily an OTC business, the building blocks

for these notes are exchange-traded futures and

options. The structured notes are based on

commodity indices or custom-built commodity

baskets, with the prices generally derived from

the futures markets. Typically these notes

include a guarantee on the principal to protect

the investor from loss, and may include com-

plex payout formulas that resemble call and put

options. For example, a structured note can be

designed to pay a certain rate of return over a

specified number of years, plus an additional

amount based on the movement of a commod-

ity index or basket of commodities.

Bonnefous says this business has had

“phenomenal growth” in the past two years,

with demand coming primarily from institu-

tional investors and high net worth clients

who see the commodity markets as an alter-

native asset class.

(Will Acworth, Jean-Marc Bonnefous

Head of Commodity Derivatives, BNP Paribas, BNP Paribas Strategy, Futures Industry, March/April 2006)

2 sigma move?

Would have guessed 3 +

what is the difference in production of heavy sour to light sweet world wide? Don’t know? that is the true question that the powers that be don’t seem to want to tell anybody

We are seeing demand destruction , not supply growth.

Oil prices will correlate with economic growth in an overall downward trend as Peak Oil sets in. The correlation will be that of an inelastic commodity but reflect the increasing scarcity of oil.

The evidence suggested here for the oil supply is very short term and does not reflect the demand destruction . Indeed if the economies in Japan, the EU and the US continue to shrink oil supply will be adequate for some time.

Faber said it himself , the recession began in October. I guess if we can live with a increasingly shrinking economy there is no problem.

Yves

I think you have nailed the issue at the top of your post. There is an asymmetry in oil price response to “news”. Up $4 on Nigerian “events”, down $2 on falling demand, up $5 on Israeli nuclear war maneuvers, down $1 on vast new oil field finds.

The asymmetry is characteristic of bubble tops, and the cause is short covering, as a modest amount of buying sends shorts scurrying. Watch this psychology turn around when the price breaks the $125 level. As Mr Faber points out, bubbles can burst quickly and the results can be amusing. Some TV icons were touting coal stocks yesterday and they took a 10% haircut today. Nice work !!

I am frankly surprised that Paul Krugman is buying the bogus arguments about all the oil traded being delivered. Not everyone understands futures contracts as well as they think they do, after all.

Wallace (BizWeek) and Sprecher (ICE) have it out.

Juan,

Thank you very much for your comment.

The TD report, “WITH ALL THE TALK ABOUT PEAK GLOBAL OIL SUPPLY,

WHAT ABOUT PEAK OIL DEMAND?” ties it all together very nicely. The supply, demand and inventory figures all seem to balance pretty well.

IEA is projecting annual demand growth of 1.6 percent over the next five years. TD shows a mere .4 percent so far this year and projects that to fall even farther. I suppose the question becomes: Who to believe?

Like I said earlier, being the cynical old pessimist that I am, I suppose I fall in the TD camp. Also, IEA has pretty much been 100% wrong in the past, so, in my book at least, it doesn’t have much credibility left.

If the TD figures are correct, and I have no reason to doubt them, then demand growth has stalled in the first four months of 08 while at the same time supply has continued to grow. Inventories have grown. Furthermore, inventories are at historicaly high levels. All said, these are not the kind of supply/demand fundamentals that one would expect to augment prices. And yet prices continue to climb. So if it is not the supply/demand fundamentals creating the high prices, then what?

I can now see your need to find a reason for the disconnect between “the real and the financial.” And like I have said here on Naked Capitalism before, you’re pretty much the lone ranger when it comes to trying to explain the specific mechanism by which the futures market influences the spot market.

I could think of a number of reasons why oil futures might be high–risk premium due to threat of war or hurricanes, the fact that non-OPEC supply appears to have plateaued which gives OPEC much more power over oil prices than before, etc. But none of these explain why the spot prices are high.

But here’s a question for you. If the mechanism you describe is indeed determining spot prices, then why would it not continue to do so in the future?

DownSouth,

Thank you for the reply and question but one need not be a ‘cynical old pessimist’ to recognize that there have been and are problems in both the U.S. and global economy, or, what can be thought of as a globally synchronized recession in process of developing.

Such process is always uneven but in a world of interpenetrated national economies, a world of global assembly lines, cannot not but be combined. Further, on basis of decade by decade change in world GDP, weak avg. rate of nonfinancial profit (not earnings), etc, this is taking place within a particular historic context.

Capitalism’s postwar ‘golden age’ had begun ending even during the later 1960s but it took the recessions of 1970-71 (partially synchronized) and 1974-75 to deliver the message.

What grew out of these? A generalized turn to deregulation and market fundamentalisms which came to be grouped under the rubric ‘neo-liberal’ and then ‘Washington Consensus’, ‘both’ of which facilitated deeper interpenetration of nominally national economies, greater looting of less advanced regions and what became financial hypertrophy.

The financial came to dominate that which it ultimately depends upon, the real creation of new value through the processes of production.

Now, this latter circumstance has been commonplace over the history of the capital system, i.e. overproduction of means of production and falling rate of profit generate attempts to offset such a fall through speculative activities. Such turns to making money from money or, differently, to substitute speculative gains for real losses have, at base, been driven by differential rates of return between trade in fictitious capital, mere claims, and profit of production.

The relationship has tended to be inverse but to my knowledge never so institutionalized as became the case during the 1980s but moreso the 1990s and this decade, something that I relate to an overdevelopment of, overdependence on, the credit system, the beginnings of which were noted even in 1974 by the Minneapolis FRB:

we have substituted credit expansion for savings as the means to finance the growth of consumer and business spending. Another dose of the old medicine would only worsen the disease, in the longer run if not immediately.

(Bruce K. MacLaury, President, Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis, 1974 Annual Report Essay)

Nevertheless, more ‘doses’ were forthcoming until, with with the de facto ending of reserve requirements (1990 and 1992 reductions + generalized use of sweep accounting by 1994), the rise of MMFs, of Government Sponsored Enterprises, of global non-bank banks; the interacting of all and more, a system of potentially unlimited expansion of credit money had come into being. I believe it was Larry Lindsey who called this a condition of “nuclear credit fission”.

In short, a form of rentier capitalism had developed and become institutionalized — such a form contains internal contradictions, manifestations of which we’ve been seeing and, as it expands claims to the real beyond this latter’s ability to generate new value, is also a more overall contradiction that, as it sharpens, is also a greater fragility and uncontrollability (both of which demand still greater ‘doses’ no matter their fatal nature).

“why would [the mechanism I desribe re determination of spot prices] not continue to do so in the future? Because the form of capitalism it is associated with will not survive; we have seen it breaking down for some time now. Rentier capitalism is a dependent form and one which is unable to reproduce itself ad infinitum no matter the levels of (increasingly desperate and deluded) institutional support.

At a lower level of abstraction, oil price regimes rise and fall. You may want to read Section 2 in the attached 2007 paper.

OPEC Pricing Power

http://www.oxfordenergy.org/pdfs/WPM31.pdf

Pardon the length but simply a quite reduced attempt to provide context to my thoughts on ‘disconnect between the real and financial’ (which is not really a ‘disconnect’ but a dialectic).

NB even though some of my above may have an ‘Austrian school’ tone, I do not subscribe to that or any other of the neoclassical ‘schools’ of economics but instead one which was initially developed as a critique of the old political economists, has been perpetually upgraded over the last roughly 130-140 years and better connects/combines theory with the motion of material realities.

so what came first, the chicken or the egg? if an investment bank forecasts higher oil prices and falling stocks, and oh, by the way, we deal in oil futures/hedge funds etc…can they actually create a price run up? and when oil prices climb $5-$10 per month or more, and if oil costs $1/mo/barrel to store, can it be worth it to buy, store, hold and sell? I’d say so..could an OPEC country by back its oil on the spot market, and fudge it production numbers, creating a hidden supply drop? they would never do that, would they?

now here is some good old fashioned conspiracy theory for you:

http://www.drudge.com/news/108749/obamas-contributor-causing-oil-crisis

Juan,

Thank you for your response. I very much agree with your philosophical framework and, being an ex-pat living in Latin America, am all too aware of the devastation that rampant neo-liberalism has left in its wake. I suppose the policies promoted so stridently by the United States are finally coming home to roost. Nestor Kirchner seems all but profetic now. In his speech to the Fourth Summit of the Americas, regarding the havoc neo-liberalism had caused in his region, he called it “a death trap, a trap that first traps and affects the weak, but then later, in one form or another, also arrives to the powerful.”

The one place I might disagree with you is to the question as to what high oil prices represent. Are they a further manifestation of market fundamentalism run amok? Or are they the antithesis of this, a refusal by non-OECD countries to participate in a market system that demands natural resources and agricultural products on the cheap?

I am currently reading a book you might find of great interest–J.H. Elliott’s Imperial Spain: 1469-1716. It offers a historical account of a conuntry that suffered many of the same problems the U.S. suffers today. It is made even more interesting because, as the author notes in the foreward, he chose not to focus soley on power, politics, personality and diplomacy in his narrative, but social, economic, cultural and inintellectual developments as well.

He talks of “the growth of a powerful rentier class in Castile, investing its money not in trade or industry but in profitable Government bonds, and living contentedly on its annuities.”

“During the [16th] century, events had conspired to disparage in the national estimation the more prosaic virtues of hard work and consistent effort. The mines of Postosi brought to the country untold wealth, if money was short today, it would be abundant again tomorrow when the treasure fleet reached Seville. Why plan, why save, why work?” Elliot asks. “There seemed little point in demeaning oneself with manual labour, when, as so often happened, the idle prospered and the toilers were left without reward.”

There are of course many other haunting similarites between imperial Spain and modern USA– the intellectual, cultural, social, military and diplomatic happenings of a far-flung and over extended empire that died from within–to make it a very intriguing and timely read.

I just wanna add oil is not problem today. We have it enough but everybody worries for the future. Saudis can boost production a lot, but WHO WILL BUY THAT MUCH OIL, when economy is shrinking demand? That is from the S/D view. What is also funny is that nobody knows how few persons who are intermediates between oil producers and consumers earn a lot of money. I heard, if price of oil goes for 10 dollars up they earn around 60 billion. Therefore they want high oil prices and their friends (big institutional players- who are shorting now) will earn also when bubble will burst. As traders we can just wait for a sign and than start shorting. I think oil will reach 200 USD or at least 170 soon (it’s inevitable). Have a nice day ;)

DownSouth;

The one place I might disagree with you is to the question as to what high oil prices represent. Are they a further manifestation of market fundamentalism run amok? Or are they the antithesis of this, a refusal by non-OECD countries to participate in a market system that demands natural resources and agricultural products on the cheap?

If price of oils was determined by cost of production/supply/demand rather than trade in financial instruments, I would place more weight on ‘refusal to participate’. As it’s developed since 1987, it strikes me that the producing nations and major integrated oilcos’ abilities to move price has been substantially diminished.

Neo-liberal market fundamentalisms include financial opening and deregulation which, in different forms, were applied on a world scale right along with the theft of public goods through privatizations, et cet — a ‘grand’ global looting had been unleashed in a (partially directed) effort to overcome systemic crisis.

Here let me repeat something which I wrote elsewhere three months ago:

‘Between 1965 and 1973, the U.S. manufacturing sector’s rate of profit fell by 40%, a decline that worsened with the 1974-5 recession, was hit again by the severe early 80’s slump, began recovering in the 1990s but peaked in 1997, falling into 2003 since which there has been some rise but – in all cases over the last decades – never to pre-1965-73 levels.

Andrew Glyn considered the world to have been “suddenly projected from boom to crisis” with the first phase of above.

The failure of political Keynesianism, and then monetarist policies to ressurect rate of profit dovetailed with a ‘we don’t know what to do so lets try 19th c laissez-faire on a world scale’ set of policies demanded by the U.S., given voice by Reagan and Thatcher in her famous statement: ‘There Is No Alternative [to a worldwide free market]’, or TINA.

Borders to capital flow in all its manifestations had to be everywhere broken; state owned industries had to be privatized; poor fiscal management had to be tightened and almost everywhere on the backs of the working class and poor as needed social services were cut and cut again. Debt payments, no matter how great a percentage of export earnings, had to be made if a govt were to expect future access to IMF and World Bank funds.

Neoclassical economists and their theories provided ideological justification; a sort of ‘we are all neoliberals now’ attitude infected world leaders until, in 1989, John Williamson coined the term ‘Washington Consensus’, which was very much not the consensus of those most subject to the various ‘shock therapies’.

So, how did the world do under this set of misguided fundamentalisms?

“Real global GDP growth averaged 4.9%a year in the Golden Age years from 1950 through 1973, but dropped to 3.4% annually in the unstable period between 1974 and1979. Dissatisfied with the instability, inflation, low profits and falling financial asset prices of the 1970s, advanced country elites pushed hard for a switch to a more business friendly political-economic system; global Neoliberalism was the result. World GDP growth averaged 3.3% a year in the early Neoliberal period of the 1980s, then slowed dramatically to 2.3% from 1990-99 as Neoliberalism strengthened, making the 1990s by far the slowest growth decade of the post war era.” (James Crotty)

As would be expected, the post-1973 annual growth rate of world real gross domestic investment fell substantially through 1996.

With the exception of parts of Asia, economic development throughout the world failed to gain traction, chronic excess capacity on one hand and credit fueled financial exuberance on the other.

Given the system’s inability to create employment so rapidly as required, a glut of labor and an expanding informal sectors as well. All the ‘better’ to intensify the international (and domestic) competition among workers, drive and hold wages down so also make consumer credit increasingly important to retention of living standards, no matter that this has been only another transfer to loan capital.

Average weekly earnings, constant 1982 dollars, for all private nonfarm workers in the U.S. peaked in 1972 at $331.59, falling to $257.95 in 1992 until ‘recovering’ to $277.57 in 2004 and likely having faltered again since then.

It is at least interesting that conditions of surplus labor, lower wages, deficit funding, tech innovations, etc, have not been able to generate another long wave expansionary phase. One might even suspect that finance has been ‘pumping’ too much from the real and that ‘long-felt unease’ is related to this.’

The primary contradictions which I’ve seen developing over the last number of decades have been:

1. the ending of national economies v. what can only be national states, a contradiction between economic mode of organization and national states.

2. progressive expansion of fictitious capital v. the possibility of satisfying such claims, a ‘satisfying’ which depends upon a) global creation of surplus value and b) substitution of credit for a relative insufficiency of realized surplus value (profit). This has provided much of the ‘advanced’ world with what is no more than a superficial prosperity even as it has also helped undermined its real basis. The spectacle of finance hides too much.

3. In combination, the above two have generated greater class, ethnic, international and subnational tensions. The social relations of the world capital system have become quite strained, which is not to say that capitalism is ‘doomed’ but that its present form has become increasingly untenable and a ‘change in state’ is almost certainly unavoidable, in fact seems to be underway.

Thanks for the book recommendation. The years during which I lived in Latin America helped open my eyes, subsequent study helped still further.