Yves here. There have been some admissions about how German deindustrialization resulted from Europe sanctions on the cheap Russian gas on which manufacturers, particularly in Germany and Italy, depended. However, I have to confess to not seeing much about the impact of Chinese exports to Germany dealing a big blow before the Russian gas self-inflicted wound. However, if you look at the sick state of pretty much every non-Chinese car manufacturer, and “ruinous competition” among Chinese EV and battery makers in China, it’s not hard to see why Germany was already wobbly before the energy cost blow. Admittedly as this article points out, Chinese machine tools were a second route for China eating Germany’s lunch.

Keep in mind the impact by sector of China’s incursion versus the cheap-energy-self-harm are different. Energy intensive concerns like chemical producers, paper plants, and aluminum makers started rapidly cutting production when the energy price increase hit.

By Dalia Marin, Senior Research Fellow Bruegel; Professor of International Economics Technical University of Munich. Originally published at VoxEU

Trade with China displaced large parts of the American workforce in the 2000s, but Germany did not experience a similar shock at the time. This column argues that the ‘China shock’ has hit the German economy since 2020, particularly in its core automobile and machinery sectors. To avoid America’s painful de-industrialisation of the 2000s, Chinese market entry in Europe should be made conditional on forming joint ventures with European firms in order to remain globally competitive. These joint ventures should be designed carefully to deliver technology transfer to Europe and build resilient upstream capacity on the continent.

In a series of influential papers, Autor et al. (2013, 2016) document that trade with China devastated large parts of the American workforce in the 2000s after China entered the World Trade Organisation (WTO) in 2001. This was quite unusual. In previous trade liberalisation episodes, some workers in the import competing sectors were displaced by foreign competition, but usually they found a job in the export-expanding sector. But the ‘China shock’, as Autor and co-authors coined it, of the 2000s was completely different. The competition was so swift, sudden, and so concentrated in particular regions that American factory workers were hit hard, and some regions were completely deindustrialised. Many of the workers moved into the service sector that paid much less than they had earned before, and some went on welfare payrolls. In 2016, Trump won the election, which Autor et al. (2020) connected to trade-related job losses.

Germany Did Not Have a China Shock in the 2000s

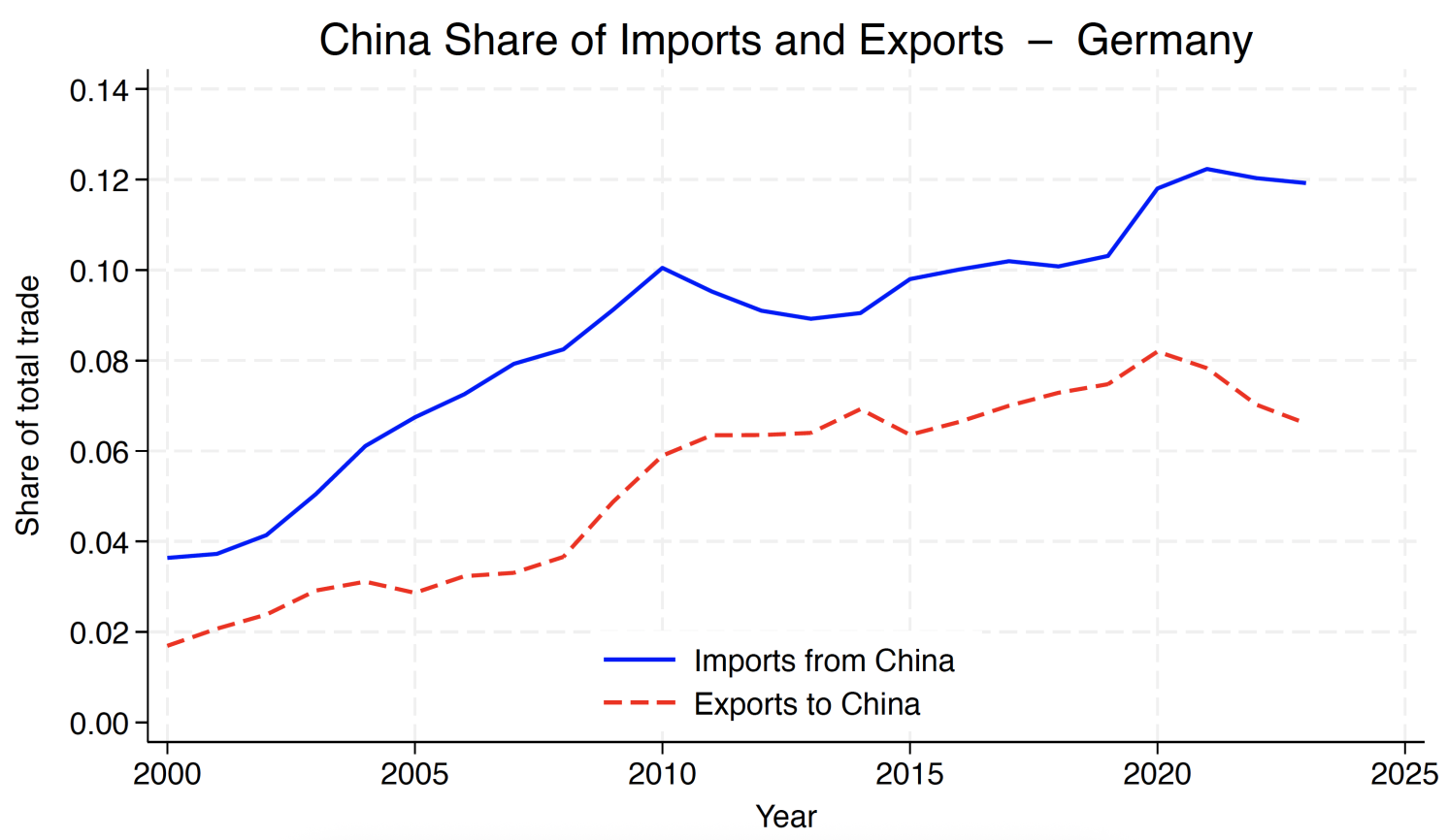

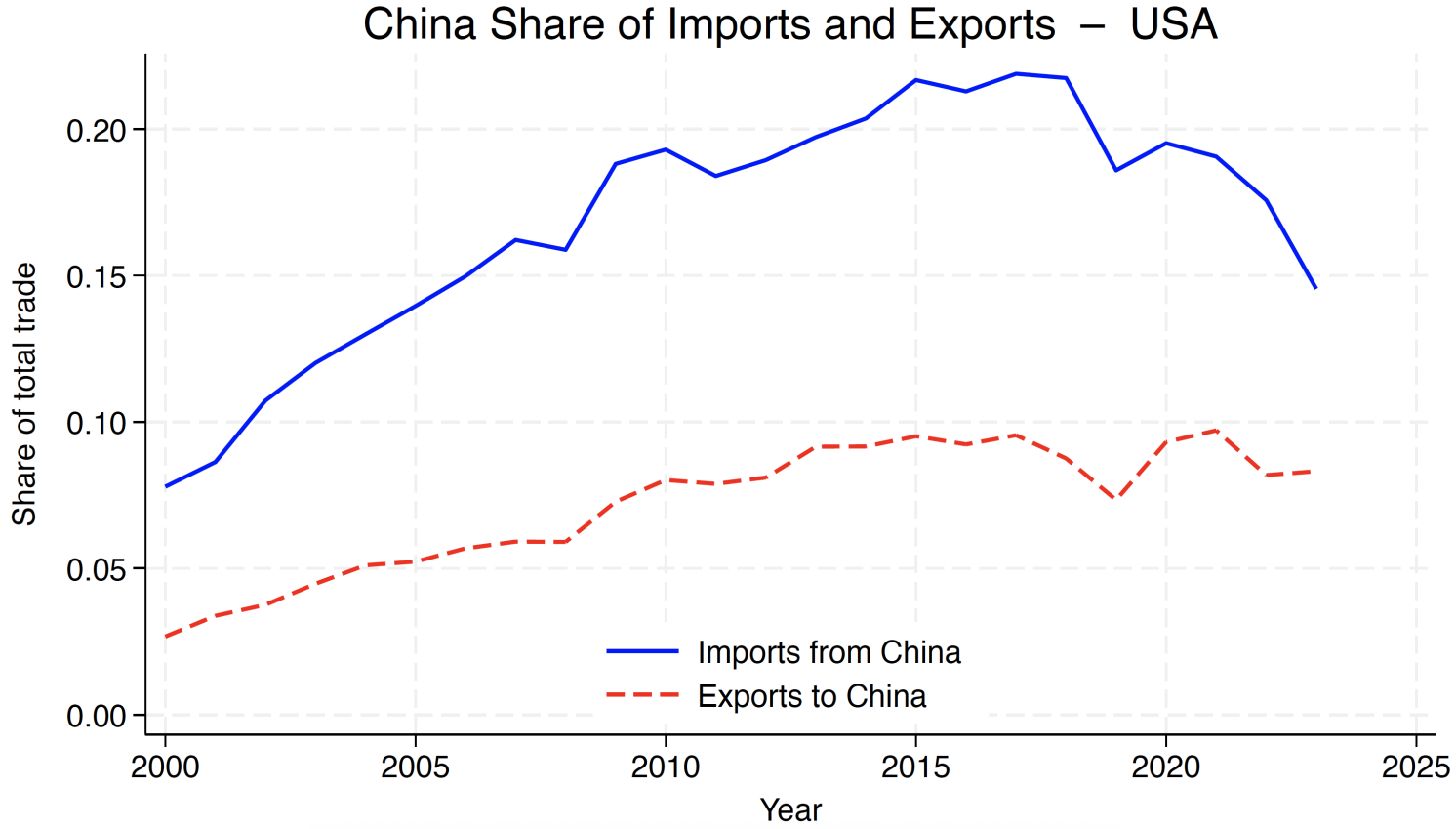

Germany did not experience a similar China shock in the 2000s (Dauth et al. 2014), although the import competition shock from China was as severe in Germany as in the US. The change in the share of Chinese imports in total imports in the period 2001- 2007 was 213.5% in Germany, from 3.7% to 7.9% (Figure 1), and in the US it grew by 188% from 8.6% to 16.2% (Figure 2).

Figure 1 China’s share of total imports and exports in Germany

Figure 2 China’s share of total imports and exports in the US

In contrast to the US, Germany’s exports to China boomed. Its export share to China increased by 227% from 3.3% of total exports in 2007 to 7.5% in 2019 as Germany’s machine tools and auto industries helped to industrialise the Chinese economy (Figure 1). In the US, exports to China as a share of total exports increased by a meagre 23.7% in the same period (Figure 2). 1

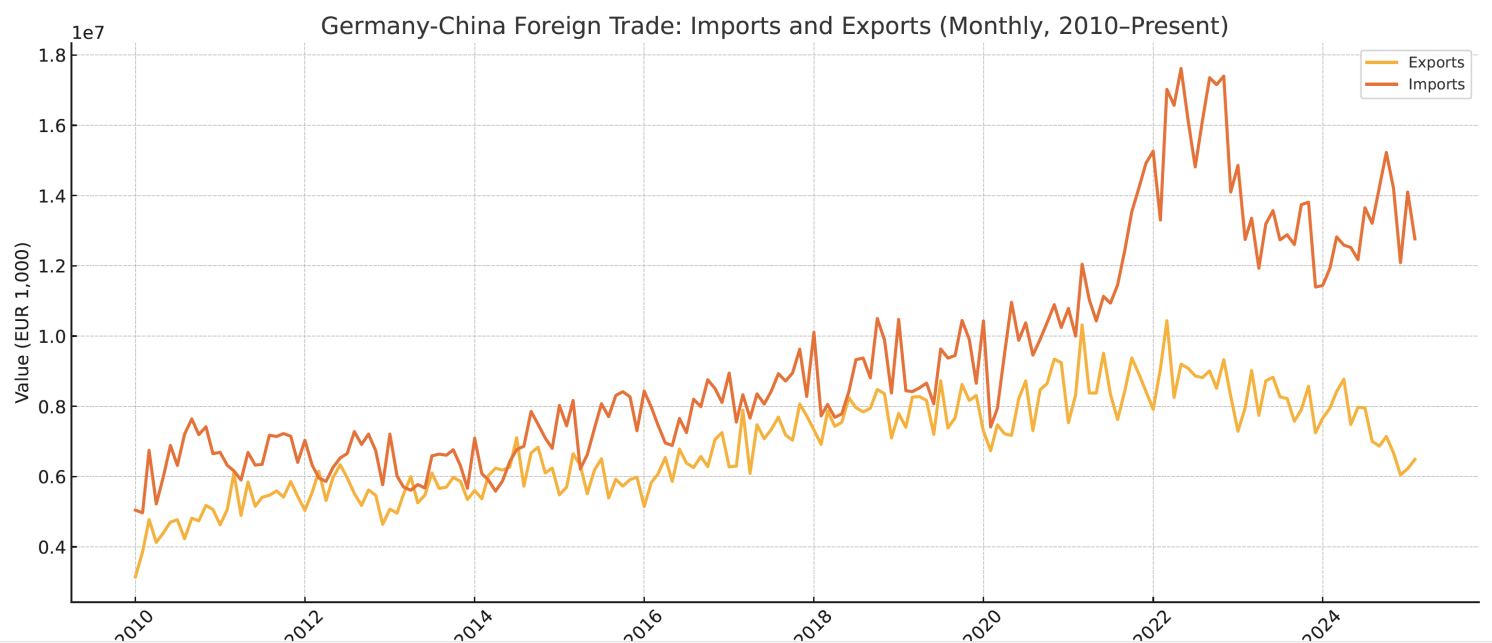

Germany’s China Shock of 2020

Germany’s trade with China changed abruptly after 2020. Between 2020 and 2022 imports from Chinese increased by more than 60% based on official data from the German Statistical Office (Figure 3). In late 2023, Germany terminated its national purchase subsidies for battery electric vehicles known as the ‘environmental bonus’ which favoured in particular the import of Chinese electric vehicles. Moreover, in 2024 the European Commission introduced tariffs on imports of battery electric vehicles from China of up to 45.3%. Brussels also imposed tariffs on imports of mobile access equipment (construction equipment) from China ranging from 20.6% to 66.7%. Further import duties were introduced on a range of chemical products. These measures contributed to a sudden decline in Chinese imports in 2023-2024.

Figure 3 Since 2020, imports from China are exploding

The historic shift in Germany’s trade pattern with China can be seen in Figure 1. Within three years from 2019 to 2022 China’s share in German imports increased by 30% from 10% to 13%. Exports to China also suffered, reducing China’s share in total exports by 20%.

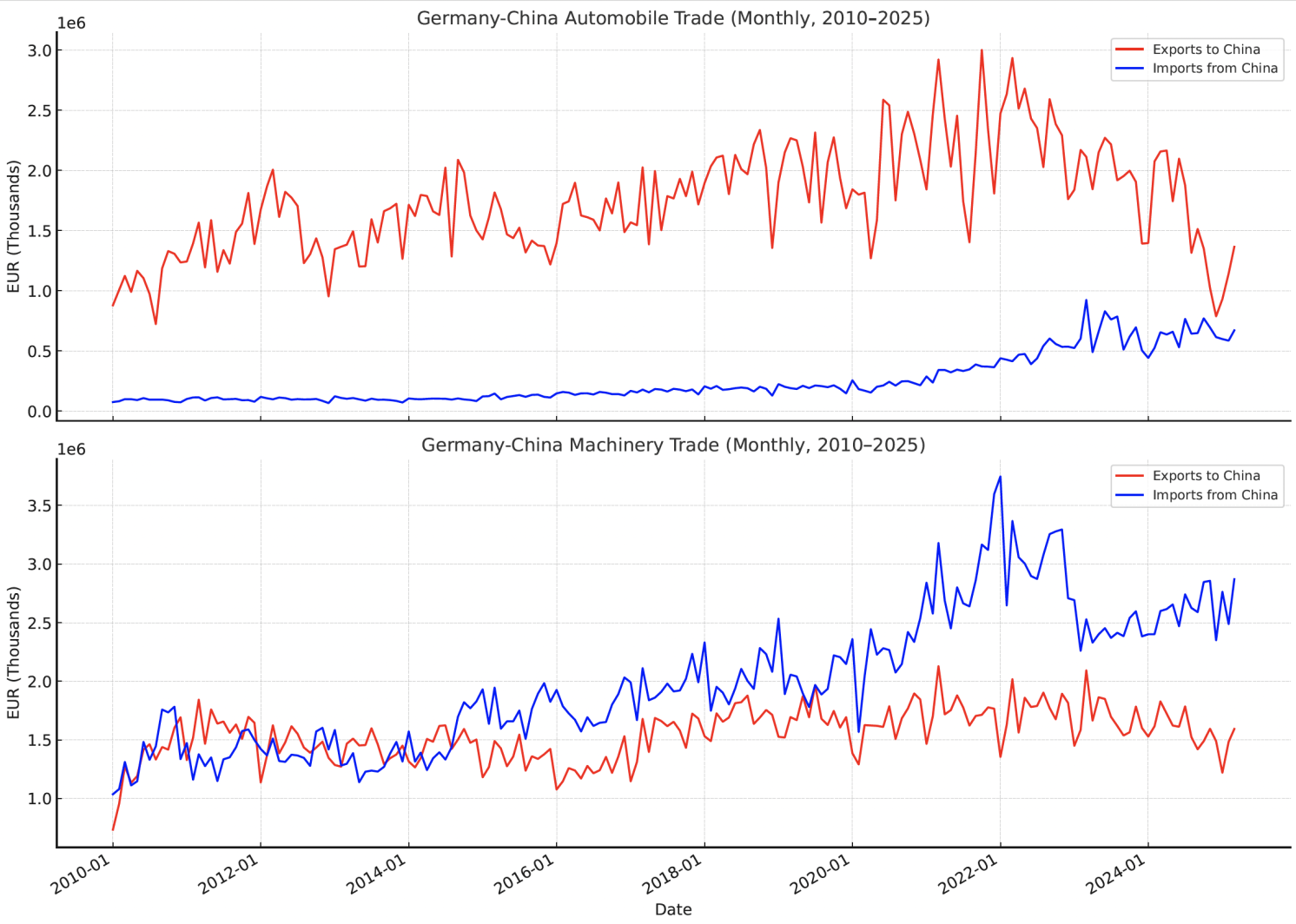

What is driving this trade pattern? Figure 4 documents that the two core industries in Germany – cars and machinery tools – experienced a historic shift. In both industries Germany stopped being a net exporter to China. Car exports to China dramatically declined by almost 70% between 2022 and 2024. Fierce competition in China and Chinese advancement in electric vehicles made Chinese consumers move from German to Chinese models. At the same time, car imports from China more than doubled between 2020 and 2023 before declining in 2023-2024 after the imposition of import tariffs on electric vehicles from China. For the first time ever, trade in cars with China is somewhat balanced in late 2024.

In machinery trade, Germany became a net importer of machinery tools from China already in 2015. Machinery imports from China more than doubled between 2020 and 2022 before declining over 2023-2024 after import tariffs were introduced. Machinery exports to China are stagnating. Given the importance of machinery imports from Germany for the industrialisation of the Chinese economy, this development is dramatic.

Figure 4 Germany’s car and machinery trade with China

The tables have turned. China is now the world leader in batteries and electric vehicles (and machinery), while Germany was the world leader in the combustion engine. China’s size, experience, and subsidies have helped China to learn and to scale up production. In a classic paper that introduces learning curves into trade models, Krugman (1987) shows that subsidies can speed up the learning process and boost the productivity of subsidised sectors, thereby putting competitors at a permanent disadvantage. Krugman’s theoretical argument has recently found empirical support by Lane (2025). Using South Korea’s sector-specific industrial strategy under President Park Chung-hee as a natural experiment, he found that, on average, subsidised industries experienced an average growth rate 80% higher than non-subsidised ones. The growth advantage persisted even after the subsidy was removed, underscoring the learning effect. Thus, Germany faces the threat of losing two of its core sectors to Chinese competition. Europe will need to keep import tariffs to facilitate learning in the face of the transition to electric vehicles and battery technology. The European Commission should also encourage Chinese investment in Europe (Marin 2024).

Europe Should Make Market Access Conditional on Joint Ventures

Germany and Europe should avoid America’s painful deindustrialisation of the 2000s. Germany’s China shock will be worse than the one the US experienced in the 2000s as cars and machinery are two of the core sectors of the German economy. These two sectors undertake most of Germany’s R&D and they play an important role for future technology and innovation. In the US, the China shock hit low-cost industries such as furniture, textiles, and clothing.

To this end, Germany should reverse-engineer China’s industrial policy by making market entry to the European market conditional on forming joint ventures with European firms. I warned two years ago about a possible China shock (Marin 2023a, b) and I suggested that the European Commission should broker a partnership with China by providing China with access to the European market in return for a commitment to invest in Europe and to establish joint ventures with European firms. Over the past 20-30 years, China has required foreign investors to form joint ventures as a condition for entry to the large Chinese market. By working with Chinese electric vehicle and battery manufacturers, German automakers could acquire the technical expertise in electric vehicles and batteries to remain globally competitive. The European Commission has adopted this policy in 2024 (Financial Times 2024) and introduced the ‘Industrial Action Plan for the European Automotive Sector’ in 2025 (European Commission 2025).

Early challenges and failures by European firms producing batteries without a foreign partner reinforce the need for partnership with China. Two important examples are Northvolt and ACC (the Airbus of batteries), a joint venture between Mercedes, Stellantis, and Total Energies. In both cases the core problem was to scale up production. In the start-up phase, European battery firms experienced a scrap rate of batteries of nearly 90%. They go through a valley of death until batteries become profitable (Les Echos 2025a, b, Financial Times 2025). By the time they become profitable, however, they might be out of the market. Partnering with Chinese EV and battery firms would allow European firms to skip the start-up phase and to move directly to profitability.

For this to work, joint venture contracts with Chinese firms must be carefully designed to make sure that Chinese investment delivers technology transfer to Europe. The danger is that these joint ventures will remain locked in assembly activity without learning. The European Commission should ask for a 50/50 ownership share between European and Chinese partners and require China to send a 25-30% share of Chinese professionals to these joint ventures to train European partners. To build resilient upstream capacity, local European input requirements are also desirable.

Summary

In this column, I document that the China shock has arrived in Germany, threatening its core sectors: cars and machinery. I also discuss what the European Commission should do to prevent a deindustrialisation shock even worse than the one the US experienced in the 2000s.

See original post for references

India also a big country, why only China work so hard ?

A grim determination to emerge from “the century of humiliation” such that China would never again be submitted to Western arrogance and predation?

Wouldn’t that imply the Chinese weren’t working hard before the 19thC?

Industrialized Europe smashing into imperial China certainly was a shock, but high quality Chinese exports go back centuries before that.

Marco Polo went off to get them in the 13thC and Christopher Columbus in the 15thC

Oh, Indian people don’t work hard. Was that the problem? The angle of your cant. . . wanting.

The short version of the story is that China fought it’s way to independence, whereas India’s “independence” was granted to it.

From this it followed that China has centralized political power, public sector banking and central bank under government control, while India has a system imposed by British to keep India disunited and under commercial banks ruled by BIS, IMF and World Bank – a.k.a. neocolonialism.

I think anyone who looked at the consequences of moving from ICE to EVs would crater the German car industry which had been the core of the German economy. This was clear for the last 10 years , as Germany went all in with net zero , the green energy movement and then compounded by the self harm of Russian energy embargoes. Its an example of economic self destruction, which is being closely followed by that of the UK.

The issue is not that the German car industry moved to EVs but that they didn’t do so fast enough.

Their economy was built on the mittelstand, which serviced the ICE vehicle industry.

There is no reason to jettison ICE except for ideology, the same ideology that created the energiewende. Add in a US engineered Russophobia and the destruction of an economy is complete.

The issue is, they didn’t need to do any of this.

EVs will be/are cheaper and more efficient than ICEs, especially with the electrification of the economy. It’s like insisting on horse carriages in face of automobiles.

The problem is that neoliberal western elites are incapable of doing anything, they just issue fatwas about closing this and raising prices of that, but to actually build anything, which can replace the old things? That is not for them to do, someone else is supposed to do the hard work. And if you insist, they refer you to the market, which after all can solve every problem just by itself and for free.

I am becoming ever more impressed with Chinese industrial planning. This article makes sense, but the author’s demands at the end entail Europe begging for so much help so late in the game after China has so much leverage.

Is the European market really worth it, especially if any knowledge from “learning” would also surely wind up in American companies over time?

China has so many natural resources, a long term industrial strategy, and a big lead in several new industries. I was also impressed reading about their major companies open-sourcing AI models. Besides Meta I don’t know any American companies who did that.

Both Germany and China run up huge trade surpluses. Consequently, the idea that they can form an effective trade partnership seems improbable. Germany and Europe are going to go down very hard if they do not take drastic action, and maybe they are finally starting to see this, as they are being shunted brusquely from US markets while being undermined by the super competitive Chinese at home. Hence the push (in part) for heavy militarization in Germany to keep the wheels of industry humming, something already noted. In the longer run, it seems hard to believe that the EU will not take protective measures to save what industry it still has. Looks as if the fragmentation of the global economy is bound to intensify.

As BMW said 2 years ago: “We are the best with ICE in the world and so there is no reason why we should switch”.

Please correct me but in essence electric engine has been around long enough too, at least as a basic concept (I don´t talk about the battery). But there were rather short sighted reasons to ignore EVs and what everyone knew would happen eventually.

Of course mass transportation was subsumed under this mindset. Instead of changing the hierarchy: Car-manufacturers should serve the purpose and need of mass transportation.

So the same that is true for ICE is true for car-based public transport. Metropolitan regions simply can´t bear any more from a certain level upwards. But that was never seriously taken into consideration.

I don´t know of a single German city where you can seriously drive through during the week. It is a nightmare.

From my older experience in Eastern Europe it´s the same there.

It is well established that by the 1960s any progressive and future-oriented city planning on the large scale in Germany was repeatedly rejected and undermined by the car-manufacturing lobby.

Cities such as Munich, Cologne, Hamburg, Berlin document this very well.

In Munich the Olympic area that was built for 1972 Olympic games attempted for the first time to somehow at least merge both “lobbies”.

Among others it was Munich long-time SPD mayor Hans-Jochen Vogel (died 2020) who attempted this shift. He was in office 1960-1981. However needless to say that as Munich mayor essentially you cannot govern against the carbuilders.

A well-known bone of contention was “autogerechte Stadt” – Wiki translates it as “Automotive city” – which was of course mirrored in other major European countries.

On the industrial level ICE and cars were never seriously questioned. To oppose “Automotive city” and make non-car concepts viable was a token to voters´ interests who lived increasingly in densly populated areas but altogether a half-hearted or even fake one as with most progressive ideas of that era if we look at the large picture and how things did develop in the long run.

A free text by German daily WELT from 2013 on this 1960s-70s “struggle”. Use google to translate.

When Munich almost came under the wheels

by Rudolf Stumberger

Published on 13.07.2013

https://www.welt.de/regionales/muenchen/article117994708/Stadtautobahn-Als-Muenchen-fast-unter-die-Raeder-gekommen-waere.html

As one of the opposing, progressive urban planners/architects of that time, Karl Klühspies (died 2023), points out in the end of above WELT text and which is mostly conveniently overlooked as another important factor in such high-stake fights:

“Critics of urban planning found it difficult to survive as architects in Munich. Klühspies worked extensively outside the state capital, later also in the USA.”

Klühspies also worked in China and warned of privatizing German railways. In Germany he never made it into a powerful position.

That BMW rep is living the dream. In the US, BMW ICE cars have a very poor service record. The most reliable ICE cars are made by Toyota and Honda.

ha! ha!

that´s the SAME every honest mechanic will tell you – “buy Japanese” they tell you or “My wife has a Toyota”.

I too have a 30 year old Japanese. It´s doing what they used to say about VW in the ad – it´s running and running and running and…

German manufacturerers have had a dismal record as you write for 20 years certainly.

p.s. I don´t know enough about cars to however judge that phrase that I first encountered by Andrei Martyanov, argueing German cars were overmanufactured. Not sure about that for the car industry/history at large. When Martyanov said something about that his own car has video cams front and back I did think he must have a screw loose regardless of some excellent scholarship he has been doing…I for sure am doing the parking without a single chip, sensor or beep.

p.p.s. May be you remember that scene in “Ford vs. Ferrari” when the hero, driver Ken Miles, insults the Ford rep for their latest Mustang because it´s huge, heavy and lousy.

1st half I think

3 min.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ibhXLKGaL3A

There’s a very well understood trade-off in the automotive world between performance and leading edge gadgetry on one side versus reliabililty. Cars like Lambos are not reliable. If you want reliability, go Toyota every time and it’s been like that since forever, and for most people that’s the best option. Toyotas are automotive manifestations of perfection. But if you want sexy you go for the Beamer et al.

What about Ferrari?

Same. Think thoroughbred horses as an analogy; built for speed and beauty, not reliability.

Interesting. If this were common wisdom it would destroy at least the myth.

How about Lambo tractors?

That’d be a Urus. Same, minus the beauty and handling. What idiot would buy that?

the European Commission should broker a partnership with China by providing China with access to the European market in return for a commitment to invest in Europe and to establish joint ventures with European firms….By working with Chinese electric vehicle and battery manufacturers, German automakers could acquire the technical expertise in electric vehicles and batteries to remain globally competitive

I don’t know about mid-market cars like VW, but the servicing charges on marques like BMW, Audi, Mercedes, Porsche, etc., are CRAZY high (which is why we have a Lexus, not a German vehicle – service charges are a third of the Germans).

EVs require, AIUI, much less service in terms of parts and labor than ICE vehicles. I’m guessing this captive regular income is one reason why German marques were very (too?) late to switch to EVs.

Reading the future wring is what killed Kodak (I was part of the digital division, and involved in high-level decisions of film vs. digital). Looks like Germany’s hubris has done the same to its auto sector.

BTW, when I did onboarding at Kodak we were explicitly told we had no competitors: they were ‘other manufacturers’.

I remember a 2018 conversation with someone who identified as a retired CFO of a retail chain here in Northern CA.

As I drove an EV (Chevy Bolt), he remarked that the servicing revenue was $300 per year for EVs vs $1300 per year for ICE and that would be painful for the dealers.

The 2017 Bolt now has close to 100K miles on it, and the servicing cost has not been close to $300/year.

Regenerative braking has allowed the brakes to last the near 100k miles.

Occasionally the radio/climate display goes non-responsive, but the internet provided reset instructions.

One battery failcode was generated, but that may have resulted because the dealer didn’t sufficiently tighten one of the 12v battery terminals after the main battery was replaced under a recall.

I’ve spent many hours adjusting valves, changing oil, rebuilding engines, transmissions and clutches on the older ICE cars I owned in the past.

The EV is a stark difference.

I’m waiting for the next gen EV Bolt II to hit the market next year before I buy my next new car. Assuming GM doesn’t pull the plug, as it did with the EV1, the Volt and Bolt I.

Your experience of Bolt I suggests that Bolt II should sell well in the low-price economy car segment, but will it be profitable? I believe GM, Ford and Chrysler are offering mostly EV versions of existing ICE models for the upscale market.

The big question is: can the US make affordable (mass market) EVs, and how much time (and Federal subsidies) will be required to see the EV transition through???

If the legacy ICE automakers can’t make the transition to affordable EVs, given their current business models, the Federal Government should let China’s EVs into the U.S. market.

Big Oil — and the UAW — may not let this happen, though.

I follow a guy who still shoots large format on film and has sunk some money in kit. I watch his photos and weep.

Big German companies and thousands of Mittelstand companies invested in China. They have factories there. When looking at German imports from China, how much of that are German companies exporting out of China back to Germany? How much of that are components made by German companies in China sent to Germany for final assembly so that they could bear Made in Germnay label? Now let’s look at real Chinese exports, I mean by companies owned by Chinese – can Germans seriousy expect that they will remain competitive when Chinese work 6 days a week and Germans 4.5 days a week? Can Germany be competitive when German employees can stay at home when they want because they do not need to see a doctor anymore? Can Germany be competitive when hardly anyone on shop floor in Western part of Germany is not German?

“can Germans seriousy expect that they will remain competitive when Chinese work 6 days a week and Germans 4.5 days a week? Can Germany be competitive when German employees can stay at home when they want because they do not need to see a doctor anymore?”

Perfect example of a race to the bottom mentality. While you’re at it, cut healthcare benefits and social programs and cut salaries in half. That’ll make Germans even more competitive and will no doubt reduce social tensions.

“Can Germany be competitive when hardly anyone on shop floor in Western part of Germany is not German?”

Are you saying Germany needs more immigrants in order to become competitive or did you inadvertently add an extra word there?

Sounds to me like you haven’t really thought this through.

Listening to “Inside China Business” talking about shortages of rare earths (RE) due to China blocking and actively seeking to block cheating of RE exports that may end in weapons systems – demanding detailed proof they are not dual use, including plans and sensitive information (as the US and Europe still do wrt Xinjiang).*

RE-derivative components, especially magnets, motors, and batteries, underlie the new electric mobility industries, such as drones and cars (and weapons). Virtually all these supply chains run through China. The US and EU purposefully relocated RE refining (and its pollution) to China, which now has process know-how and university departments that are gone in the neoliberal West. This led to the derivative products being largely Chinese (e.g., drone motors). This disadvantage will not be overcome without long-term industrial policy (verboten in the neo-liberal West) with significant government subsidies (which the EU actively deprecates). A generational effort is needed, including recreating university RE minerology and chemistry departments and ensuring their students will have a career, i.e., long-term stable industrial planning. Yet, the Trump uncertainty is disabling even short-term US (and its EU vassal) planning.

How will Germany compete with Chinese companies with local access to these critical, energy-intensive components? Energy costs (including for refining) are one of many factors underlying the hyper-competitiveness of Chinese products against German manufacturers now that Chinese precision exceeds that of the West in many cases**.

One cannot separate geopolitics from geo-economics — the EU will never allow its military industrial companies (and Metz envisions more dual-use production) to partner with Chinese companies, particularly when the US is pressing NATO to prepare for a war against China.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mAyMVr2vorU

**I use many inclinometers (0.1°) in my lab that I buy directly from China (10 days to arrive). They cost $100 ($30 now for tariffs) with awesome customer service. The closest US version is $4,000, and US customer service generally sucks bigly (unless you personally know the CEO). Chinese higher precision models (0.01°) are tens of thousands in the US – and unavailable outside the MICC. They are mostly used in Chinese machine tools and imaging hardware, etc. This is a clear case of the MICC killing civilian industries, e.g., machine tools, warnings I recall from the 1980s.

Technology transfer from China to Europe? That sounds like a bad joke. Has Europe really fallen so far?

“Technology” doesn’t stand still. What was cutting edge 20 yrs ago is obsolete today. If you’re not building things at the cutting edge, you don’t know how to do so anymore. If your ‘investment’ $$s go to bonuses and stock buybacks instead of R&D, you’re just falling behind. See ISL’s footnote for just a tiny example, and then realize the same thing is happening to every component, and more importantly, to every manufacturer of every component.

Gunpowder?

Or things returning to 1000 years ago, maybe.

Gunpowder? Paper? Magnetic compass? Silk? Porcelain? Stirrups (Ok, not exactly “China” there…)?

This is an interesting article. People get wrapped around the axle hating on the President but don’t seem to realize the tariffs are more about industrial policy than anything. So because the USA doesn’t have a comprehensive industrial policy, we get the blunt instrument of tariffs. Tariffs work, witness the data supporting the article.

Thus, I predict China will cut deals for EU access just as they will cut deals for USA access (as did the South Koreans, Japanese, and Germans – witness Hyundai, Nissan, Mercedes, and BMW plants scattered about the USA). And this, exactly as both USA and the EU cut deals for Chinese access (Buick is bigger in China than in USA and the most popular Buick in USA was developed in China). Ditto Apple production and know-how promulgating the rocket-like rise of Taiwan’s Foxconn in China, leading to Hauwei, et al.

That all this also resulted in USA loosing jobs in textile manufacturing, furniture, and such, was not overnight and there were loud complaints but lacking industrial policy, nothing happened. So now the Germans are losing machine tools and autos, and this too was predictable because there’s no such thing as a free lunch. The Germans knew good and well the Chinese are just as smart, industrious, and ambitious as themselves and thus, also knew they would use the German machine tools to replicate western made machines, and use this as a leg up. But like our American businessmen, they were so greedy they saw the short term sales, only.

So reciprocal access will be granted or trade barriers will be enacted. At least this is my prediction.

After all, it’s my view there’s precious little difference in some German guy, an American guy, or a Chinese guy. They basically each want their rice bowl left undisturbed so they may work, then go home to families and live their life in peace.

And will come a time when the subcontinent, the Middle East, and Africa join the party. Already China seeks to move lower profitability industries around to Vietnam, as an example. How long before capital switches focus? Also happening now is capital looking to India. I’m just sad we screwed the Russians instead of bringing them into the fold after the wall fell, but in my defense, nobody asked me.

I almost blanked out when I reached, “the European Commission should broker a partnership with China…” and seemed to have fallen through the looking glass. Yeah. Right. That sounds like the ideal job for Useless and Kaya Badass. And then I realised that it was just a masterly satirical comment on the European élites propensity to fail really, really BIG in everything apart from ensuring their own personal welfare at the expense of the very people they are supposed to serve.

Well said.

The mighty United States of America demanding technology transfer from China in exchange for economic access. . . that would have been rich. Europe will have to swallow hard, too, before making that demand. Colonialist pride goeth before a crash.