By Manmohan Singh and Peter Stella. Manmohan Singh is a Senior Economist at the IMF in Washington, DC. Peter Stella is Director of Stellar Consulting LLC. Originally published at VoxEU.

One of the financial system’s chief roles is to provide credit for worthy investments. Some very deep changes are happening to this system – changes that surprisingly few people are aware of. This column presents a quick sketch of the modern credit creation and then discusses the deep changes are that are affecting it – what we call the ‘other deleveraging’.

Modern credit creation without central bank reserves

In the simple textbook view, savers deposit their money with banks and banks make loans to investors (Mankiw 2010). The textbook view, however, is no longer a sufficient description of the credit creation process. A great deal of credit is created through so-called ‘collateral chains’.

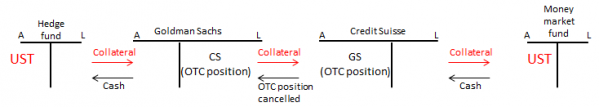

We start from two principles: credit creation is money creation, and short-term credit is generally extended by private agents against collateral. Money creation and collateral are thus joined at the hip, so to speak. In the traditional money creation process, collateral consists of central bank reserves; in the modern private money creation process, collateral is in the eye of the beholder. Here is an example.

A Hong Kong hedge fund may get financing from UBS secured by collateral pledged to the UBS bank’s UK affiliate – say, Indonesian bonds. Naturally, there will be a haircut on the pledged collateral (i.e. each borrower, the hedge fund in this example, will have to pledge more than $1 of collateral for each $1 of credit).

These bonds are ‘pledged collateral’ as far as UBS is concerned and under modern legal practices, they can be ‘re-used’. This is the part that may strike non-specialists as novel; collateral that backs one loan can in turn be used as collateral against further loans, so the same underlying asset ends up as securing loans worth multiples of its value. Of course the re-pledging cannot go on forever as haircuts progressively reduce the credit-raising potential of the underlying asset, but ultimately, several lenders are counting on the underlying assets as backup in case things go wrong.

To take an example of re-pledging, there may be demand for the Indonesia bonds from a pension fund in Chile. As since these credit-for-collateral deals are intermediated by the large global banks, the demand and supply can meet only if UBS trusts the Chilean pension fund’s global bank, say Santander as a reliable counterparty till the tenor of the onward pledge.

Plainly this re-use of pledged collateral creates credit in a way that is analogous to the traditional money-creation process, i.e. the lending-deposit-relending process based on central bank reserves. Specifically in this analogy, the Indonesian bonds are like high-powered money, the haircut is like the reserve ratio, and the number of re-pledgings (the ‘length’ of the collateral chain) is like the money multiplier.

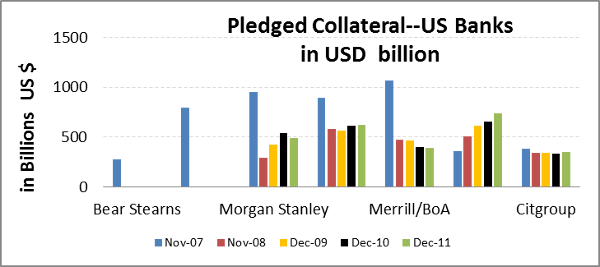

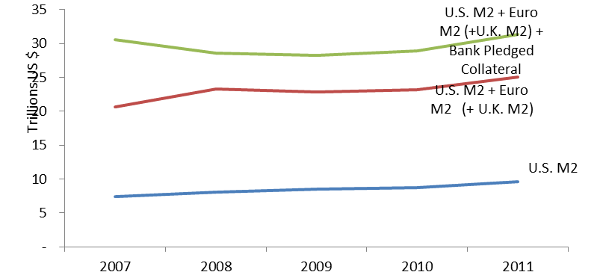

To get an idea on magnitudes, at the end of 2007 the world’s large banks received about $10 trillion in pledged collateral; since this is pledged for credit, the volume of pledged assets is a good measure of the private credit creation. For the same period, the primary source collateral (from hedge funds and custodians on behalf of their clients) that was intermediated by the same banks was about $3.4 trillion. So the ratio (or re-use rate of collateral) was around 3 times as of end-2007. For comparison to the $10 trillion figure, the US M2 was about $7 trillion in 2007, so this credit-creation-via-collateral-chains is a major source of credit in today’s financial system. Figure 1 shows the amounts for big banks in the US and Europe.

Figure 1. Pledged collateral that can be re-used with large European and US banks

An example

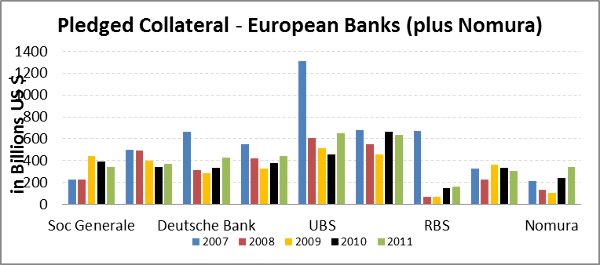

As this process is unfamiliar to many non-specialists, consider another example. Figure 2 illustrates how a piece of collateral (e.g., US Treasury bond) may be used by a hedge fund to get financing from a prime-broker (say, Goldman Sachs). The same collateral may be used by Goldman to pay Credit Suisse on an OTC derivative position where Goldman was ‘out-of-the-money’ to Credit Suisse. And then Credit Suisse may finally pass the US Treasury bond to a money market fund that will hold it for a short tenor (or till maturity). Notice that the same Treasury bond has been used twice three times as collateral for extensions of credit – from the original hedge-fund owner to the money market fund.

Figure 2. An example of a collateral chain

The other deleveraging

Comparing private and traditional money creation, a critical difference is that private credit creation turns on banks’ trust of each other. New credit gets created only if the onward pledging occurs and this depends, for example, on UBS’s trust in Santander as a counterparty in the first example. Due to heightened counterparty risk, onward pledging may not occur and the collateral thus remains idle in the sense that it creates no extra credit.

To put it differently, a key difference between the trade and pledge-collateral credit creation processes is the role of governments. The traditional textbook money multiplier is based on insured deposits and thus largely a creature of government regulation and the central bank’s lender of last resort assurance. The collateral multiplier is very much a creature of the market.1 The multiplier – which essentially measures how efficient illiquid assets can be converted into liquid collateral and thus credit – varies with the extent to which markets views a given asset classes as ‘liquid’ in normal and stressed markets.

This brings us to the key policy point. The ‘other’ deleveraging. In this new private-money-creation process, there are three distinct ways of reducing credit.

- Increase the haircut (like raising the reserve requirement);

- Reduce the supply of assets that can be used for pledging; and

- Reduce the re-pledging of pledged collateral (shortening the collateral chain).

Most recent research has focused on the first. Balance sheet shrinkage due to ‘price declines’ (i.e., increased haircuts) has been studied extensively – including the recent April 2012 Global Financial Stability Report of the IMF and the European Banking Association recapitalisation study (2011).

In this column we raise the flag on the second and (more importantly) the third way. When market tensions rise – especially when the health of banks comes under a shadow – holders of pledged collateral may not want to onward pledge to other banks.

- With fewer trusted counterparties in the market owing to elevated counterparty risk, this leads to stranded liquidity pools, incomplete markets, idle collateral and shorter collateral chains, missed trades and deleveraging.

- In practical terms, the ratio of pledged-collateral (which is a measure of the credit thus created) to underlying assets falls as this onward pledging, or interconnectedness, of the banking system shrinks.

This ratio decreased from about 3 to about 2.4 as of end 2010 – largely due to heightened counterparty risk within the financial system in the present environment. These figures are not rebounding as per end 2011 financial statements of banks – see Table 1 and Figure 1. Indeed, anecdotal evidence suggests even more collateral constraints recently.

Table 1. Sources of pledged collateral, re-use and overall collateral

Source: Velocity of Pledged Collateral – update, Singh (2011)

Consequences of the other deleveraging: The cost of credit

Reduced market interconnectedness, or the trend toward ‘fortress’ balance sheets, may be viewed positively from a financial stability perspective if one simply views each institution in isolation. However, the vulnerabilities that have resulted from the weakened fabric of the market may yet to have become fully evident. Since the end of 2007, the loss in collateral flow is estimated at $4-$5 trillion, stemming from both shorter collateral chains and increased ‘idle’ collateral due to institutional ring-fencing; the knock-on impact is higher credit costs for the economy.

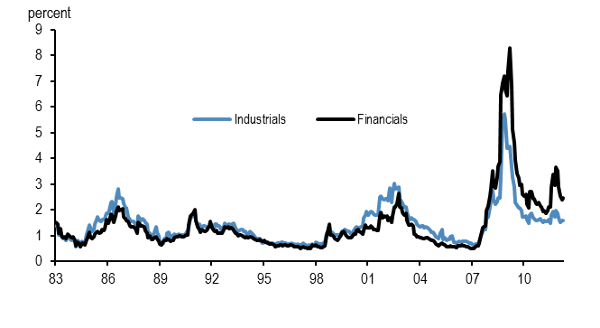

Relative to mid-2007, the primary indices that measure aggregate borrowing cost (e.g., BBB index) are well over 2.5 times in the US and 4 times in the Eurozone. This is after adjusting for the central bank rate cuts, which have lowered the total cost of borrowing for similar corporates (e.g., in the US, from about 6% in 2006 to about 4% at present). Figure 3 shows that for the past three decades, the cost of borrowing for financials has been below that for non-financials; however this has changed post-Lehman. Since much of the real economy resorts to banks to borrow (aside from the large industrials), the higher borrowing cost for banks is then passed on the real economy.

Figure 3. Post-Lehman, borrowing cost for financials are higher than non-financials

Source: Barclays Intermediate, investment grade spreads (1983-2012)

Collateral and monetary policy

Since cross-border funding is important for large banks, the state of the global pledged collateral market may need to be considered when setting monetary policy.

Overall financial lubrication in the US, UK, and the Eurozone, exceeded $30 trillion before Lehman’s bankruptcy (of which 1/3rd came via pledged collateral). Certain central bank actions, such as the ECB’s LTRO, the US Federal Reserve’s qualitative easing and the Bank of England’s asset purchase facility have been effective in alleviating collateral constraints. However, these ‘conventional’ actions, to the extent they merely exchange bank reserves for collateral of prime standing (such as US Treasuries), do not address the issue credit creation via collateral re-pledging (Singh and Stella 2012).

The ‘kinks’ in the red line (Figure 4) M2 expansion due to QE but much of the ‘easing’ for good collateral is deposited with the central banks and is not available to fund lending. As of end-2011, the overall financial lubrication is back over $30 trillion but the ‘mix’ is in favour of money which not only has lower re-use than pledged collateral but much of it ‘sits’ in central banks.

Figure 4. Overall financial lubrication – M2 and pledged collateral

Policy issues

As the ‘other’ deleveraging continues, the financial system remains short of high-grade collateral that can be re-pledged. Recent official sector efforts such as ECB’s ‘flexibility’ (and the ELA programs of national central banks in the Eurozone) in accepting ‘bad’ collateral attempts to keep the good/bad collateral ratio in the market higher than otherwise. But, if such moves become part of the central banker’s standard toolkit, the fiscal aspects and risks associated with such policies cannot be ignored. By so doing, the central banks have interposed themselves as risk-taking intermediaries with the potential to bring significant unintended consequences.

Authors’ note: Views expressed are of the authors only and not of the International Monetary Fund.

References

Copeland, A, A Martin, and M Walker (2010), “The Tri-party Repo Market Before the 2010 Reforms”, Federal Reserve Bank of New York Staff Report No. 477.

EBA (2011), 2011 EU-wide stress test results.

IMF (2012), Global Financial Stability Report, April.

Mankiw, Greg (2010), Macroeconomics, Worth Publishers; Seventh Edition. Shin, Hyun. S (2009), “Collateral Shortage and Debt Capacity” (unpublished note).

Singh, Manmohan (2011), “Velocity of Pledged Collateral – Analysis and Implications”, IMF Working Paper 11/256.

Singh, Manmohan and Peter Stella (2012), “Money and Collateral”, IMF Working Paper No. 12/95.

1 This is why we ignore implicit/explicit government back-stops collateral markets such as Triparty repo in the US that does not reflect market clearing prices (Copeland et al. 2009) and/or where onward pledging of the collateral may be limited (e.g., to the primary dealer club only).

Quite educational. Thanks for the effort. I do have a two-part question though.

Is the assumption used here that the yet to be be revalued real estate everywhere is marked to fiction still? Assuming so, what additional impacts would a needed valuation reset have individually and collectively on those banks?

I’ll wager they’re still doing accounting fraud to keep insolvent banks afloat. Banks stole back significant amount of the collateral via foreclosure, but RE values are falling, and appear likely to continue falling, and they haven’t resold even a fraction of the RE on the bank books.

The banks have a problem, all this collateral that nobody wants to borrow to purchase, so banks continue being landlords until prices fall enough.

I’ve never seen more confused political leadership in my life. It’s as if they’ve bought the bankers’ line so completely that they’ve lost their eyesight.

It’s all so simple really;

ask yourself; Who benefits most from bubbles/bursts of phony baloney?

Right

the Pink Slime

Love

I am also interested to know what effect unlimited money printing will have? As long as there is deleveraging underway, wages cannot rise, so feeding money into the banks will minimize the impact of #2 and #3.

The only substantial effect of this collateral chain is the continual recapitalization of asset values. Virtually all of the collateral is deployed in speculation. That is why the stock market has decoupled from the so called real economy. As for real estate, its collateral value has shrunk dramatically and most of the dreck has been passed along to the Fed, which explains the explosion of its balance sheet. This is one world wide game of musical chairs in which the object is to ride one asset class after another on the way up and bail out once the suckers begin to pile in. If you don’t know who the sucker is, it is you.

Debt Money means we can never get out of debt. We need money that is money without debt.

http://www.monetary.org/2012-conference

http://monetary.org/2012schedule.html

Announcing the 8th Annual AMI Monetary Reform Conference

at University Center in downtown Chicago, Sept. 20-23, 2012

Discount of $110 Now Available

Minimum donation is $285 to attend the 2012 Conference – Take this opportunity to sign up today!

Register by phone at (224) 805-2200

Scheduled Speakers for our 2012 8th Annual AMI Monetary Reform Conference

American Monetary Institute proudly announces its 8th annual Monetary Reform Conference in Chicago. Our conferences launched the modern grass roots movement for U.S. monetary reform and thereby World reform. You are invited to attend this important meeting in beautiful downtown Chicago. Our money system clearly needs a serious overhaul to secure economic justice, peace and prosperity as we enter the 3rd Millennium. True reform, not mere regulation, is necessary to move humanity away from a World dominated by fraud, warfare and ugliness and toward a World of justice and beauty. You can avoid discouragement and join with us in this adventure to achieve positive money results for America and the world.

Don’t be discouraged because the villians who created the present crisis, have manipulated governments to bail them out. The media, which has made such “errors” possible, and the economic theories behind banker activities already stand accused in the public mind.

Main Themes of the Conference: Implementing Monetary Reform now!

The Conference examines the essential elements of monetary reform needed to place time on the side of justice. We focus on Congressman Dennis Kucinich’s National Emergency Employment Defense Act (NEED, HR 2990), introduced into Congress on September 21, 2011, which contains the necessary provisions to achieve real and lasting monetary reform.

We continue examining the problem of usury. Is it a necessary part of “free market economics?” Is it a destroyer of nations? Or is it both? The deeper concept of usury is an anti-social misuse of the money mechanism for private gain. This classical definition of usury is how our present privatized monetary system malfunctions.

A Different Kind of Monetary Conference

The situation in which real monetary reformers find ourselves is that after years of study, we already know most of the broad shapes that monetary reform must take. These views have stood the test of time, and challenges from those with less experience or operating under misconceptions or pursuing non-reform agendas. It is time to implement the elements that must be part of good reform.

What are these broad national parameters supported by over 3000 years of history? That the control of the money system must shift away from private control toward governmental control. Away from commodity money notions; away from fractional reserve banking – using debt for money. Towards money issued interest free by government and spent into circulation for the common good. All serious reformers understand that we must replace our private credit system with a government money system, ending what is known as fractional reserve banking. Anything less should be viewed as a diversion, at this critical time.

We’ll continue educating and explaining why proposals are necessary, beneficial and moral, and continue to present the historical evidence which demonstrates that. We’ll answer any serious challenges, and those arising from plain misunderstanding. We may invite selected spokesmen for differing reforms to succinctly present their case. But we’ll do it within a context of advancing the reform agenda. The direction of world events requires that we advance monetary reform now. All expert viewpoints are welcome for discussion, except disinformation!

This conference is open to the public*, and to properly organize it the AMI requires a donation of $395 per attendee. Early registrations discounts are offered. This includes conference materials and aids, coffee breaks, a Get Acquainted Reception and a Celebration Dinner and beach barbecue. Hotel and travel costs are separate at group discounts. Attendees who can are encouraged to help out with larger donations – it enables us to extend scholarships to students. Looking forward very much to seeing you and advancing monetary reform.

…….

http://www.monetary.org/intro-to-monetary-reform/faqs

7) Doesn’t your AMA proposal merely continue with a fiat money system?

Shouldn’t we be using gold and silver instead? Wouldn’t that provide a more stable money?

Our system is absolutely a fiat money system. But that’s a good thing, not a bad one. In reaction to the many problems caused by our privatized fiat money system over the decades, many Americans have blamed fiat money for our troubles, and they support using valuable commodities for money.

But Folks! The problem is not fiat money, because all advanced money is a fiat of the Law! The problem is privately issued fiat money. Then that is like a private tax on all of us imposed by those with the privilege to privately issue fiat money. Private fiat money must now stop forever!

Aristotle gave us the science of money in the 4th century B.C. which he summarized as: “Money exists not by nature but by law!” So Aristotle accurately defines money as a legal fiat.

As for gold, most systems pretending to be gold systems have been frauds which never had the gold to back up their promises. And remember if you are still in a stage of trading things (such as gold) for other things, you are still operating in some form of barter system, not a real money system, and therefore not having the potential advantages as are available through the American Monetary Act!

And finally as regards gold and silver: Please do not confuse a good investment with a good money system. From time to time gold and silver are good investments. However you want very different results from an investment than you want from a money. Obviously you want an investment to go up and keep going up. But you want money to remain fairly stable. Rising money would mean that you’d end up paying your debts in much more valuable money. For example the mortgage on your house would keep rising if the value of money kept rising.

Also, contrary to prevailing prejudice, gold and silver have both been very volatile and not stable at all. Just check out the long term gold chart.

There ought to be a way to block this kind of crap. Anything else you want to advertise, perhaps a pimple cream?

Since the delay in trying to fix Fukushima is a lack of money according to washington’s blog, then how to quickly have money that is not debt to fix this danger to all of us is important and urgent.

http://www.washingtonsblog.com/2012/05/senator-fukushima-fuel-pool-is-a-national-security-issue-for-america.html#comments

Senator: Fukushima Fuel Pool Is a National Security Issue for AMERICA

Posted on May 6, 2012 by WashingtonsBlog

snip

Fuel pool number 4 is, indeed, the top short-term threat facing humanity.

snip

Boils Down to Money

Of course, it all boils down to money … just like every other crisis the world faces today.

I’ve watched the PBS video Money, Power, and Wall Street several times in order to begin to come to an understanding of the whole financial charade that blew up in 2008 and which is right on track to blow up again any time now. Political/philosophical leanings aside, I thought it was pretty informative for the average “layman” (i.e.; one who hasn’t drunk the Kool-Aid and isn’t caught up in all the techno mumbo jumbo jargon of modern finance). Listening to some of the young rock stars who allegedly came up with all the synthetic horseshit in the early 90s that was supposed to minimize risk explain how they “never could have foreseen” it’s ultimate effects on the overall financial system, it gradually became quite apparent to me why.

The world financial system is now effectively one single, totally integrated entity. Individual banks, hedge funds, governments, central banks, and other associated organized criminal enterprises are all effectively functioning as one single integrated enterprise! And as was pointed out several times in the film, you never eliminate risk, you merely pass it around. Which is fine from the perspective of any single entity/”business unit” within the system, who are all busily scheming along in their day to day scams trying to maximize their individual take of the loot. What none of them takes into account however (or maybe they do, get to that in a minute) is that they are all part of a single integrated financial institution/criminal enterprise, and that in the event of the inevitable periodic system collapse (the system is, after all, nothing more than a classic ponzi scheme at heart) every one of them is only as strong as their weakest link; i.e. the “sucker” they’re trying to pawn their risk off on.

So, the only remaining question to be answered in my mind is, are they merely academically naive and/or stupid, or are they criminally smart in that they knew from the very start that government would have to backstop their losses? Whatever the case with the former, we now know that they’ve actively embraced the latter, and are right back at the criminal hi jinks that got us here in the first place, “fortress balance sheets” notwithstanding.

Answers? I’m clearly not that smart, but then again, I was raised to believe that we were all supposed to actually work for a living, and not simply create purposely obfuscated ponzi wealth schemes for a living. But I would think that any true and effective answer to our current predicament starts with an orderly collapse the entire current world wide ponzi wealth scheme in all of its many manifestations and applying a good measure of people’s justice to at least the main players in this colossal criminal scheme. Reforming the current system is just not possible, and idealistic attempts to do that are every bit as naive as the young bucks were who first created the current mess.

“So, the only remaining question to be answered in my mind is, are they merely academically naive and/or stupid, or are they criminally smart in that they knew from the very start that government would have to backstop their losses?”

I doubt that many of the private sector employees who lucked into a killing on the housing bubble and subsequent crisis “knew from the start.” There is that anecdote about some young person crapping his pants as he accompanies Blankey to a crisis meeting, and Blankey has to tell him he’s not getting off the boat on the shores of Dover Beach, he’s getting out of a limo at the NY Fed.

But if you look at the career of someone like Robert Rubin, who worked both sides at a very high level– where he himself engineered bank bail outs as US Treasury Secretary, as in the Latin American debt crisis– you can only conclude that he knew, and that he set up the scam from the government side and then went to Citibank to profit from it, knowing that the government would patch things up as it had in the past.

Of course, this is all dependent on having the right people in office, which he/they also worked to ensure. Rubin also still sits on the board at Harvard, an allegedly perfectly respectable person.

“”and the number of re-pledgings (the ‘length’ of the collateral chain) is like the money multiplier.””

http://www.nakedcapitalism.com/2012/04/scott-fullwiler-krugmans-flashing-neon-sign.html#comment-679315

financial matters says:

April 2, 2012 at 7:38 am

“In short (!), the money multiplier model is wrong because it has the causation backward”

Nice explanation here. Implies that productive loans are generated by credit worthy enterprises with productive ideas and these endeavors are actually hindered by our current system of private interest being siphoned off these loans. A more public system would charge more reasonable interest and feed this interest back for the common good.

Sort of another refutation of the trickle down effect. Ie the false notion that bankers trickle these loans into the economy for our own good.

“”But, if such moves become part of the central banker’s standard toolkit, the fiscal aspects and risks associated with such policies cannot be ignored. By so doing, the central banks have interposed themselves as risk-taking intermediaries with the potential to bring significant unintended consequences.”

We seem to be seeing some of these unintended consequences. Moral hazard as the financial institutions have been bailed out of their bad investments and continue with same. Bad monetary policy as money is printed to cover these bad investments rather than clearing them from the system. Ie lower home prices are what is needed for many first time home buyers to realistically enter the market. Enabling fraud by being afraid to confront the TBTF. Replacing elected legislators in enacting fiscal policies..

When I read this:

I’m hard-pressed to understand how this can pass the ‘sniff-test’ among even Very Serious People, trained, that is, in graduate business school finance and management programs.

Suppose you transfered all of basic elements in the examples you present to apply them to a game of musical-chairs. We then have the (now apparently astounding) assertion that,

“A Hong Kong hedge fund may get financing a “chair” from UBS secured by collateral pledged to the UBS bank’s UK affiliate – say, Indonesian bonds “another chair”. Naturally, there will be a haircut on the pledged collateral (i.e. each borrower, the hedge fund in this example, will have to pledge more than $1 of collateral for each $1 of credit).

These bonds “chairs are ‘pledged collateral’ as far as UBS is concerned and under modern legal practices, they can be ‘re-used’.”

Indeed?!? You mean, when “the music stops” and it actually comes time to sit down, they can be “re-used”? Please explain that part to me very s-l-o-w-l-y.

(continuing) …

It’s also not completely clear to me what difference it makes even if, as you assert, it’s “true” that “the re-pledging cannot go on forever as haircuts progressively reduce the credit-raising” … & etc. as long as it is eminently possible for the process to “go on” too long for anyone’s good–since it is simply a basic fact of the living world that “forever” is an abstraction–however so often in economics it might be appealed or referred to–which, simply, never comes, is never “reached.”

The crucial issue, then, becomes not one of “how long before the process approaches too nearly to ‘forever’?” , but rather, “how long before we actually arrive at a process which extends ‘too long’ a time?–too long for anyone’s good, that is.

Since both bonds and the ‘pledged collateral,’ whether real or imagined, supposedly “back these” are humanly-created entities, and, though not infinitely extensible, still, excessively extensible in character, what ensures that, while we never arrive at “forever”, we also never arrive at “too long for anyone’s good”?

As it seems to me, the answer was and remains today, “Nothing ensures that.”

The virtue of replacing the abstractions which are “bonds and their ‘pledged collateral’ ” with real physical entities such as “chairs,” is that it is more immediately obvious that the “chairs” may not serve more than one person per chair—when the music stops; and, as Charles P. Kindleberger tried so valiantly to remind us, “the music” always “stops” no matter how many times we persuade ourselves that “this time it’s different.”

This was a well-written and clear piece (though I’m unclear about the conclusions: how does high-grade collateral fix heightened counterparty risk?). Nevertheless, it gave me some insights about economic cycles that possibly addresses your question about how long the credit creation multiplier can be extended before problems arise.

Under favorable circumstances (good ethics, stable population, productive economy), credit can be created vastly faster than real goods/services. A supertanker cannot be built as fast as a keyboard entry can be made. By necessity, the rate of growth of collateral, limited by real world constraints, is much slower than the rate of credit creation. Thus credit creation, if it proceeds too rapidly, will outpace collateral creation as well as ‘consume’ existing collateral until not enough collateral remains to extend the process. Thus credit creation slows down/stops but credit still needs to be serviced within a now overextended economy (i.e. credit creation ‘overshot’ reality). At this point a contraction is likely to ensue.

To avoid this, one has to reverse the three mentioned ways of reducing credit, that is: (i) decrease the haircut; (ii)

increase the supply of assets that can be used for pledging (e.g. by lowering the rating required); (iii) increase the re-pledging of pledged collateral (extend the collateral chain); as well as (iv) increase the rate of collateral formation (real collateral and/or – not recommended – synthetic collateral).

To my mind, only (iv) can avoid problems, thus credit creation ought to be limited to the pace at which an economy can grow naturally/has grown recently. No doubt, some will argue that growth should be juiced with more credit and/or credit acceleration.

Could someone please direct me to any banker who’d say “Yes, sure!” (and sincerely mean that) to my loan-application after I’ve admitted that, in fact, the collateral I’m pledging has already been “pledged” elsewhere, or, that is, real terms, “I don’t really own (control) this collateral.” ?

Or, try another analogy: a blood-bank. Imagine that blood-banks were run the same way.

You need blood, so, going to the blood-bank, you get some, it saves your life, and in return, you’re supposed to donate blood in turn, but you propose instead to pledge a donation of blood. What would happen if lots of “borrowers” proposed giving not only pledges of blood-collateral but re-pledging an pre-existing pledge of blood?

Clearly, there’s no problem unless of course there comes a sudden need for nearly all of these pledges to made-good. What then? This is, of course, the equivalent of the music stopping in the musical chairs when numerous people have relied on pre-pledged “chairs” rather than real ones.

1) In the simple textbook view? Mankiw? Pleeze! Banks do not need deposits to make loans. They loan capital, not reserves.

2) Credit creation is money creation? If that were true, banks could never go broke. If that were true, loans on banks’ books would be single entry transactions. Neither of these is true, but both would have to be if banks created money.

This from the IMF? My head hurts.

Inter-bank lending does allow banks to “create money” since it enables them to “borrow back” their net liabilities to other banks. During good times it is like we have one huge bank. During bad times, the banks don’t trust each other’s assets and the system breaks down.

My head hurts. Benedict@Large

That’s a normal reaction to learning about banking. Also puking in disgust. Also rage.

Benedict@Large,

Banks only create credit money but not cash money (reserves).

Another way to keep a bank from collapsing is to merge it with another big bank. Lender of last resort is not the only way to save a collapsing bank. We can keep merging them until we have just a few very large banks.

http://aquinums-razor.blogspot.com/2010/07/why-is-deflation-and-depression.html

mansoor h. khan

… They loan capital, not reserves. ..

erm, no.

They loan “fiction” ..and almost all love a great novel

Love

Yes, Benedict, it is as Mansoor says. Credit creation, debt creation is money creation. Banks do create money, because their credit/debt is good, exchangeable money, basically because the government says so. Of course nobody can create somebody else’s debt. (Except governments, practically speaking).

Banks don’t loan capital or reserves. Governments puts capital constraints on bank lending and almost meaningless reserve regulations. Without them, their lending is unconstrained.

Bank money is just not as good money as government money = government debt. It’s lower on the pyramid of money, is negotiable in a smaller sphere, because they aren’t as powerful as governments.

Yet.

Bill Mitchell calls the debt of a monetary sovereign government “corporate welfare.” Why do we tolerate it? Cause the banks love it?

So are derivatives a way to play the music backwards? I think I hear the devil.

once again, the Fed opened Pandors’s box, letting all corporations create “money,” in hopes of closing the hole in the Titanic, by hiding it from view…

This is good stuff but I’m not sure it’s entirely accurate.

It seems to me the process described is simply moving existing money around, not creating new money.

However, the process no doubt moves existing money around in a way that levitates asset values.

Otherwise, if A gives collateral to B for a loan, and B hands it to C for a loan, and C to D, etc. Then D owes C who owes B who owes A. But A, B, C and D had to have the money, in all cases, BEFORE they lent it. So the lending didn’t create the money — it may have simply moved money that each entity already had from somplace else — however the lending, by definition of itself, created the liquidity that levitates the value of the collateral. This seems to me to be the key.

Moreover, if A can’t pay back B, then everyone else is unaffected UNLESS B relies on A paying it so it can then pay C. If B can borrow money from Z to pay C, then there’s no ill effect down the line.

If say A and C BOTH can’t pay their loans, then B and D have to borrow from Z, and each is OK.

Moreover #2, if there’s a widespread collapse in confidence in the value of collateral, then of course the willingness to move money around (i.e. liqudity) collapses, further impairing collateral values.

But I don’t see how any of this is “money” being created, although I do see it is liquidity being created.

However #3, even at a more theoretical level, all of this is a very Newtonian vision of what money is — like moving tennis balls around with raquets as collateral. The balls have to exist, a priori, as do the raquets, for everything to go. But the lending of the tennis balls back and forth doesn’t create new tennis balls. However, it does levitate the value of raquets.

One could say that banks create new tennis balls in a mathematical process analagous to what is described, but when the shadow banks lend tennis balls, they create only liquidity and levitate asset prices. And when the liquidity collapses, so do the asset prices. But I don’t think it is new money.

At least, this is as far as I got on the bus this morning. Maybe I’m completely wrong. It happens.

What’s not being created is real value, which ultimately comes from natural resources. I love this site and its commentators. They’ve taught me a great deal, but reaching the limits to growth explains why values cannot be re-inflated. How about mark-to-oil? or mark-to-natural resources? The system’s “ability” to convince many astute people that we’ve got plenty of oil is fascinating. We don’t have plenty of cheap oil -it’s gone; and it matters greatly to the political/economy and finance.

Thanks. Very interesting. I kept reading and waiting for the term “Repo” (repurchase market) to come up but it never did. There are similarities but still crucial differences ( where repo takes place: hedge funds and the major Wall Street Funds are still the main actors) but the time frame in Repo is shorter and the leverage higher. My sense is the quality of the collateral is lower, but that remains to be established.

Repo, next to Interest Rate Swaps, may be the murkiest of the murky, the unspeakable, untouchable core of the private financial system that “we” out “here” don’t get to see, but have to pick the tab up for when it collapses. The average citizen cannot take their 10,000, or 100,000 or even 1,000,000 in to “lever up,” the denominations are higher; who sets those limits, and does any public regulatory agency participate, and if so who? If it was all over the counter, then no one was setting the parameters except the private “house.” How much of that picture changed with Dodd-Frank?

Happy to be corrected, but my sense of the Repo market is that’s where those placing large bets on various Euro bonds, indexes and CDSs go to leverage up into the hundreds of millions if not billions for their “bets.”

And a final question: am I even allowed to ask about REPO in pubic?

A quote which answers my own question, taken from the website “Repo Watch,” edited by Mary Fricker, here at

http://repowatch.org/about-repo/

“Repo has a flaw: It is vulnerable to panic, that is, ‘depositors’ may ‘withdraw’ their money at any time, forcing the system into massive deleveraging. We saw this over and over again with demand deposits in all of U.S. history prior to deposit insurance. This problem has not been addressed by the Dodd-Frank legislation. So, it could happen again. The next shock could be a sovereign default, a crash of some important market — who knows what it might be?” –Gary B. Gorton, Professor of Management and Finance, Yale School of Management, August 14, 2010.

*****

Here is how the bankers’ game works:

http://aquinums-razor.blogspot.com/2011/11/here-is-how-bankers-game-works.html

mansoor h. khan

On deleveraging:

http://aquinums-razor.blogspot.com/2010/07/why-is-deflation-and-depression.html

mansoor h. khan

Fantastic link. Thx a lot.

Correct me if I’m wrong, but I thought the whole scenario was quite simple, once stripped of the details and the deliberately obfuscatory terminology:

People in charge of other people’s money found that they could earn a percentage of the face value for themselves every time they traded representations (derivatives) of that money back and forth with each other.

So they invented many new ways to represent that money (and debt based on it, and bets on earnings, and bets on bets, etc.), and traded the paper around as fast as possible, skimming off a personal share of the underlying value each time.

It was a musical chairs game that nobody actually playing the game could lose, since they took their winnings off the table as fast as the paychecks and bonuses arrived. When the music stopped, they were all just fine, thank you. The losers are those whose money (and pensions and homes) got played with by the professionals, who had after decades of effort managed to get government off their backs (as they would put it).

Is there really more to it than that? Apart from the fascinating story of the way the game got “consent” from the governed and their representatives in the first place?

I know some pretty big company’s that are financing on a month to month basis or job to job. If anything goes wrong, the principles walk with zero exposure, not so much for everyone else. This has been an accelerating view to risk in the global economy over the last 20ish years in my book.

Skippy… hence the need to government back stop primary market participants.

Great article, but the conclusions are unclear to me. COuld the authors do an update and state the stakes?

I thought that Mark C. Taylor had a very simple and elegant way of stating the trends covered in Modern Money Creation, including “Repo” in his unde-apppreciated book from 2004; “Confidence Games: Money and Markets in a World Without Redemption.” He does acknowledge many contributors over the centuries, including “alchemy” from the Middle Ages,” and dreams of a “perpetual motion machine,” from even earlier classical times. But here it is: Infinite Leverage from ever shrinking collateral.

It’s very straightforward to find out any matter on net as compared to textbooks, as I found this article at this web site.