The Financial Times has caught a significant revolving door that its business press peers have largely overlooked.

In a front page story, the pink paper points out that the incoming chief counsel for the SEC has an outstanding suit against him from his last incarnation, as head of compliance for the Americas for Deutsche Bank. An overview:

Robert Rice joined the SEC last week, working directly for Mary Jo White, the new SEC chairman. He moved from Deutsche where he was head of governance, litigation and regulation for the Americas.

Eric Ben-Artzi, a former Deutsche risk manager, filed a discrimination complaint with the US Department of Labor last year, alleging he was fired after telling the SEC that Germany’s biggest bank had hidden billions of dollars of losses with mismarked derivatives positions.

In this complaint, seen by the Financial Times, Mr Ben-Artzi named Mr Rice, along with four other Deutsche executives, as a respondent. The complaint describes several meetings with Deutsche officials, including Mr Rice…

Mr Ben-Artzi, along with at least two other former Deutsche employees acting independently, went to the SEC with a range of allegations against the bank during the past three years. The common thread was a claim that Deutsche executives reduced their losses during the financial crisis by not properly marking derivatives positions known as leveraged super senior trades. The former employees estimated Deutsche should have recognised losses of $4bn-$12bn during the crisis.

We wrote about the case last year in a series of posts. The underlying trade in question was a MEGO (My Eyes Glaze Over) type, a pre-crisis confection called a leveraged super senior trade. The extensive attachments to Ben-Artzi’s complaint made it clear (once you parsed them) that the valuation of this very large trade was basically a kludge. Ben-Artzi had been hired from Goldman to address that, and was pretty much prevented from doing his job, and then fired.

The reason this is a big deal is Deutsche’s losses on the trade would have been as much as $12 billion versus $45 billion of equity. And it had to go through what was called “the largest credit resturcturing in history” to dodge that bullet. Both the Bundesbank and the SEC are investigating the complaints about this trade.

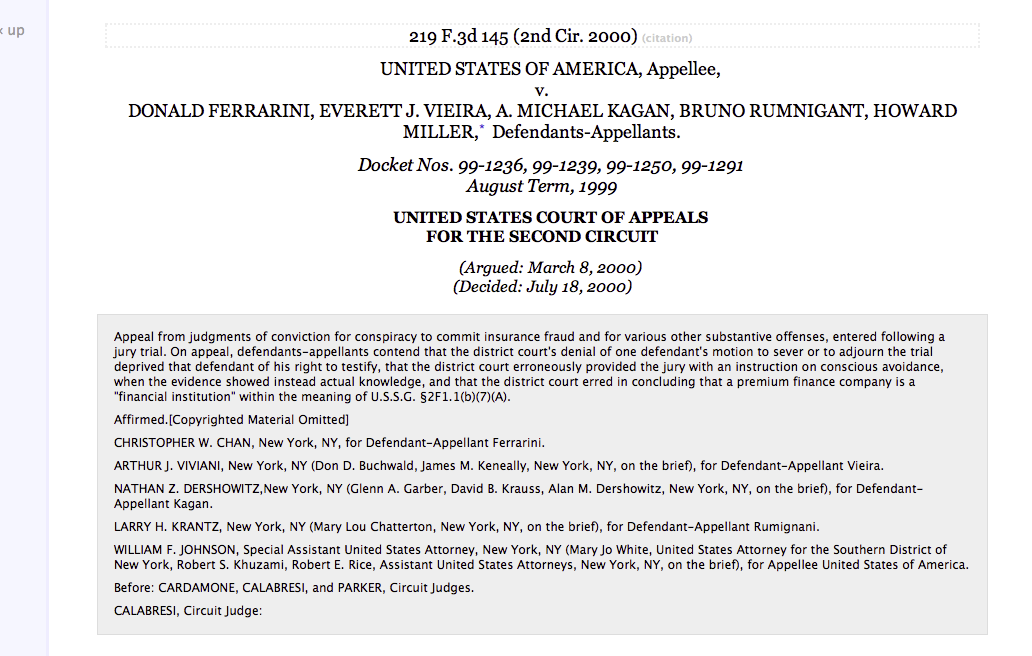

But that isn’t the really juicy part. What this little impropriety highlights is the way Deutsche is replicating the “Government Sachs” routine at the SEC. We’ve discussed at length how the former SEC enforcement chief, Robert Khuzami, was in the Deutsche Bank general counsel for the Americas 2004 to 2009. As we wrote last year:

Khuzami’s was complicit in some of the worst behavior during the crisis. He should have resigned when it became clear that CDOs were central to the crisis and the SEC would not be able to avoid dealing with them. The SEC appears to have taken a policy of suing on one CDO per major firm and settling. This is heinous, since each and every one of these firms sold more than one CDO and the bad practices were pervasive. From a December 2011 post:

So why has the SEC not pursued this area more vigorously? …

Look no further for an answer than the SEC chief of enforcement, Robert Khuzami… He was General Counsel for the Americas for Deutsche Bank from 2004 to 2009. That means he had oversight responsibility for the arguable patient zero of the CDO business, one Greg Lippmann, a senior trader at Deutsche, who played a major role in the growth of the CDOs, and in particular, synthetic or hybrid CDOs, which required enlisting short sellers and packaging the credit default swaps they liked, typically on the BBB tranches of the very worst subprime bonds, into CDOs that were then sold to unsuspecting longs. (Readers of Michael Lewis’ The Big Short will remember Lippmann featured prominently. That is not an accident of Lewis’ device of selecting particular actors on which to hang his narrative, but reflects Lippmann’s considerable role in developing that product).

Any serious investigation of CDO bad practices would implicate Deutsche Bank, and presumably, Khuzami. Why was a Goldman Abacus trade probed, and not deals from Deutsche Bank’s similar CDO program, Start? Khuzami simply can’t afford to dig too deeply in this toxic terrain; questions would correctly be raised as to why Deutsche was not being scrutinized similarly. And recusing himself would be insufficient. Do you really think staffers are sufficiently inattentive of the politics so as to pursue investigations aggressively that might damage the head of their unit?

Back to the current post. Having Khuzami at the SEC sure worked out nicely for the German bank. Notice the complete absence of Deutsche from the list of financial-crisis-related enforcement actions by the SEC.

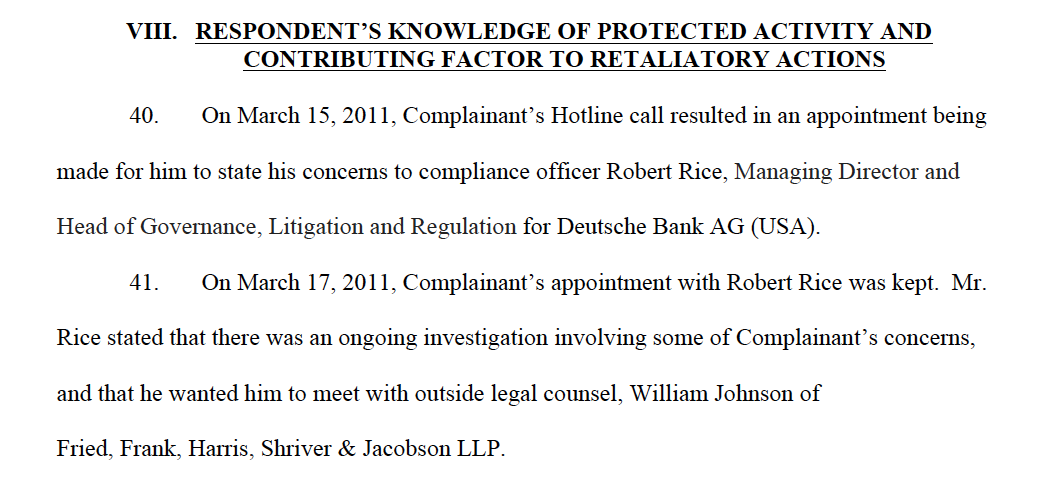

And you can be sure that the SEC will continue in its practice of seeing nothing amiss at Deutsche as far as Ben-Artzi and his fellow whistleblowers are concerned. Not only was Rice directly involved in the effort to, um, contend with Ben-Artzi’s compliant to the SEC, but it turns out another key figure involved in that incident is also a long-standing colleague of Mary Jo White. See below:

Notice that name, William Johnson, who is on the same team as Mary Jo White, Robert Rice, and Robert Khuzami? He was outside counsel to Deutsche. From Ben-Artzi’s complaint (click to enlarge):

And if that isn’t incestuous enough, the FT reminds us that Dick Walker, Deutsche’s general counsel, was the head of enforcement at the SEC.

This sort of cronyism would be bad with any large financial firm, but it is particularly troubling in the case of Deutsche. In a May Economix post, Marc Jarsulic and Simon Johnson describe how the German bank looked close to brink in 2008 and got lots of stealthy help from the Fed:

Deutsche Bank is not currently in obvious trouble, but during the financial stress and instability at the end of 2008, the Taunus Corporation, the American subsidiary of Deutsche Bank, looked very vulnerable to the financial storm building around it. Although the bank had more than $396 billion in assets, making it one the top 10 bank-holding companies in the United States, it had equity of negative $1.4 billion on an accounting basis (i.e., its assets were worth less than its liabilities)…

It was not clear how much help Taunus’s thinly capitalized global parent could or would provide….the Federal Reserve stepped in to replace short-term creditors that chose to run on Taunus. Taunus borrowing — through the discount window, the Term Auction Facility, the Primary Dealer Credit Facility, the Term Securities Lending Facility and Single-Tranche Open Market Operations — peaked at $66 billion in October 2008.

The Federal Reserve also began huge currency swaps with the European Central Bank, making it possible for Deutsche Bank to swap euros for dollars and meet the dollar funding needs of Taunus …

Deutsche Bank (and indirectly Taunus) was also greatly assisted by the Fed and Treasury decision to rescue A.I.G. Deutsche Bank received $11.8 billion as a result of that rescue (in payments covering A.I.G. credit default swap and securities lending obligations that otherwise would not have paid out).

Taunus received this help from the United States government because its failure would have intensified an already chaotic financial situation. It was not provided because the Federal Reserve knew that, once the storm passed, Taunus’s assets would be sufficient to repay its creditors. Accounting data said otherwise, and it was not possible for the Fed or anyone else to estimate the fundamental values of the assets located in the 180-odd Taunus subsidiaries. Taunus got United States government support because it was simply too big and too interwoven with the American financial system to fail.

And Deutsche remains, in the words of a recent FT article, “one of the least well capitalized big banks in the world.” So in the event of a mishap, you can be sure the German bank will be back at the Fed’s trough, and the tender ministrations of its allies at the SEC will have played a role in the failure to clean up its accounting and risk-taking.

Excellent work.

During the thirty odd years I observed the SEC professionally as an outsider market participant, the only serious problems were systemic sloth and incompetence. This was amusing but not terribly disturbing (or surprising either), since government service typically attracts those whose get up and go has long since got up and went, and bonehead leadership is practically guaranteed by political cronyism in appointments and the amazing (and hardly coincidental) number of mentally challenged offspring of Congressional charlatans and Washington-Wall Street poobahs planted within the staff.

These days the SEC appears fully engaged in supporting the Wall Street rackets and is clearly another branch of the propaganda public relations apparatus. Government regulation may theoretically provide answers to social problems, but we have long ago left theoretically behind and regulatory capture is pretty much all we now have to show for the whole Progressive Movement.

It must be ten years or so that I met an American, got into conversation about the SEC and he opined that the then Commissioners had been appointed to ensure that the SEC did not ‘see’ what was going on. That was the Bush administration.

The Republicans are progressives?

It just dawned on me that the Fed, SEC and our entire government is responsible for the triage keeping Deutsche Bank alive. Everybody is blaming Germany. But it’s us. We are the ones causing hardship for Club Med and devastation in Greece. Austerity is our technique, it keeps DB alive because the money loaned out in “bail-outs” is very expensive and it goes straight back to DB! There is essentially no money available to help Spain, Portugal, Italy, Greece, etc.

Glad that CNN caught up with your reporting!!

http://management.fortune.cnn.com/2013/06/12/sec-mary-jo-white/

Yves writes:

Fuckin welfare queens!

RE: Eric Ben-Artzi — how common are these lower-key whistleblowing events? There seems to be two parts to the issue: 1) The misdeed (crime?) of not reporting losses that they were obligated to, 2) The unjust firing of Mr. Ben-Artzi for blowing the whistle on that misconduct to the SEC.

The SEC used to be about protecting investors, but for a while now it’s been more about protecting the banking cartel.

I understand there has to be a balance struck between insiders who have knowledge of “complex” financial instruments and having the integrity and lacking conflicts of interest to go after them…

But how can you ever really have true investigative independence if being a bankster has become a prerequisite to investigating and prosecuting the banksters?

I wonder if it would make sense at all to really give serious bonuses or lifetime annuities to investigators/prosecutors who really stick it to the fraudulent activities of the banks. I know we already pay the guys at the SEC well enough (they aren’t on the civil service scale), but perhaps it’s not enough. Maybe it’s the brainwashed neoclassical in me that thinks the only way we can stop this is to make it monetarily worthwhile for these guys to commit “career suicide” by actually prosecuting high level bankers who are complicit in the accounting control frauds. Maybe in their heads they really do run the calculations of how much it will cost them in future income if they go after them, and the only way to beat that is to overcome the benefits of shirking by rewarding/incentivizing catching big fish.

Let the SEC team and their lawyers split the clawbacks and fines.

Ahhh… the first indications of MJW’s ‘leadership’ as part of the “Oops, I did it again (I played with your heart)” Obama Administration.

ABOLISH THE FERAL RESERVE!!

I’m a creditor in the TBW and Ocala Funding, LLC bankruptcy. In both of these bankruptcies Deutsche Bank has an approximate $1.2B claim. Both of the claims are for an interest rate swap agreement they had with Taylor, Bean & Whitaker and Ocala Funding. My question is, were they involved in the LIBOR scandal? And if so how can this claim be valid in the bankruptcy? Shouldn’t the plan trustee Neil Luria of Navigant be questioning the claim?

Here’s the claim. Recently they updated the claim and it was allowed in both bankruptcies.

Deutsche Bank Interest Rate Swap in TBW & Ocala Funding, LLC bankruptcies

http://www.scribd.com/doc/146918405/218-00002926-Deutsche-Bank-Swap-Claim

Thank you, Marcie. The Letter Agreement attached to the Proof of Claim is inspiring me to seek, by Requests for Production of Documents, all correspondence, written agreements, and documents related to Credit Default Swaps for which the foreclosing party will be liable to any and all counterparties.

I know the where abouts of many docs. I see if I can post links. I think this is a big deal.

http://www.scribd.com/my_content/collections

It is as some of us have said. Mary Jo White parlayed her image of a tough prosecutor into a cushy gig at Debevoise & Plimpton where she used her skills and connections (on occasion in pretty dubious ways) to defend her corporate clients. The one and only reason she was chosen to head the SEC was the full expectation that she would continue to run interference for the likes of Deutsche Bank. White is only a disappointment if you expected her act other than as she has, and will.