Yves here. I’m going a bit heavy on Europe tonight because this post, which focuses on the still unresolved debt conundrum in Europe, and the previous one, which examines current and near-term expected conditions, make for instructive reading in combination. The earlier MacroBusinesses piece dutifully records that conditions across Europe have moved (on the whole) an itty bit into the growth category, which given how awful things have been, looks a lot better on a relative basis. Plus “growth” technically is a recovery unless it is shown with the fullness of time to have been a mere bounce off the bottom.

But the MacroBusiness post also makes clear that that recovery is due to government spending, aka rising debt levels in the periphery. And that is where the VoxEu post below comes in. Pierre Pâris and Charles Wyplosz describe how the underlying European debt problems has merely been papered over and if anything has been getting worse, as the nexus between government debt and bank debt has increased. Mind you, this isn’t news per se, but somehow this underlying condition has been brushed aside as some of the vital signs of the Eurozone are looking better.

The article works through the options for resolving the situation and demonstrates the two that policy-makers have seized upon, austerity and asset sales, simply won’t succeed, and then discusses of the remaining, less politically palatable but economically tenable alternatives, which might work.

Mind you, Eurozone leaders have managed to patch things up and fend off crisis for years. Even now, we have some signs that things might be getting better, so that saying “this course of action will fail and more radical measures have to take place” seems a bit like crying wolf. But it is very hard to anticipate what will happen in Europe. Despite the appearance of improvement, the pressures are continuing to build. As I indicated earlier, some colleagues who visited several countries earlier this summer and met with well-placed economists and former officials said they thought the seismic shifts were less likely to be economic and the breakdown was more likely to take place in the political realm. What that will mean in practice is even harder to foresee than economic trajectories, and economists, despite their fondness for forecasting, are known not to have very good crystal balls.

Note that the article does come up with a fix which requires the ECB to balloon its balance sheet by 50%. That may or may not fly. But then it perversely argues that this situation should not be allowed to happen again, and points its finger at the lack of fiscal rectitude. In fact, except for known problem children (Greece, with its broken tax collection system) the blowout in government deficits in Europe was the direct result of the financial crisis, as tax revenues collapsed, unemployment and safety net payments rose, and governments stumped up to rescue bust banks. Thus the “never again” efforts should be directed first and foremost at making sure the banks don’t blow up the global economy for fun and profit.

By Pierre Pâris, Banque Pâris Bertrand Sturdza SA, and Charles Wyplosz, Professor of International Economics, Graduate Institute, Geneva. Cross posted from VoxEU

The Eurozone’s debt crisis is getting worse despite appearances to the contrary.

Eurozone bond rate spreads have narrowed – leading some to think that the crisis is fading.1 Yet the narrowing is not due to an improvement in fundamentals. It happened after the ECB announced its Outright Monetary Transactions (OMT) programme. Mario Draghi’s, “Whatever it takes”, did the trick; investors believe the ECB could and would counter rising spreads in the medium term.2

But this means that the information in the spreads is muddled:

• Spreads no longer show us what investors think about debt sustainability.

• They reflect a mix of debt-sustainability expectations and forecasts of ECB reactions.

This is yet another instance of Goodhart’s Law – a variable that becomes a policy target soon loses its reliability as an objective indicator (Goodhart 1975).

How to Gauge the Eurozone Debt Crisis

This leaves us with a coarser measure – the evolution of public debts – as a ratio to GDP. Spreads were clearly better indicators before OMT. There are plenty of problems with debt-to-GDP ratios:

• Gross debts are gross, i.e. they ignore public assets.

• Gross debts ignore unfunded public liabilities such as pensions and healthcare.

In most countries the unfunded liabilities – which include the potential costs of bailing out banks when and if they fail – are vastly bigger than the public assets that can be disposed of.

• GDP is a static measure of the ability to pay; GDP growth also matters.3

Noting that Eurozone growth seems to have slipped into a go-slow phase, the GDP denominator is likely to grow slower than it did in the 1990s.

The three points taken together suggest that debt-to-GDP ratios of the 2010s paint a more optimistic picture of sustainability than the same levels in the 1990s.

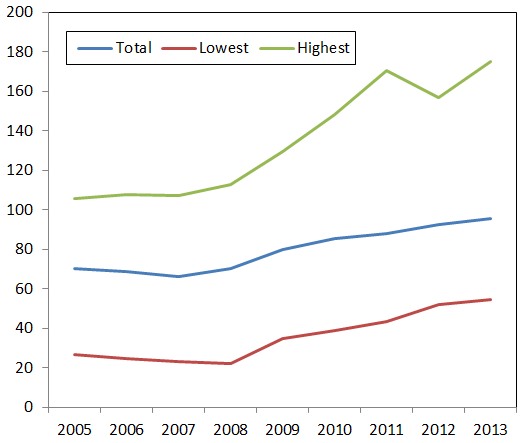

Be that as it may, Figure 1 displays the public debt to GDP ratio for the Eurozone as a whole, along with the highest and lowest member country ratios (ignoring the two special cases of Estonia and Luxembourg).

• Even including optimistic forecasts for 2013, the figure can only confirm that the situation is getting worse.

If public debt seemed likely to be unsustainable in 2008, the likelihood is even higher now. Strikingly, this holds even for Greece, in spite of the restructuring of its public debt in 2011, which was large enough to bankrupt the Cypriot banking system. Put differently, not only the initial problem has not been solved, it has also been made worse.

There can be no surprise here. Budget stabilisation cannot work during a recession as was pointed out at the outset of crisis (Giavazzi 2010, Wyplosz 2010).

Figure 1. Debt to GDP ratios in the Eurozone (%)

Source: AMECO-on-line, European Commission.

What are the Options Today?

The debt problem cannot be avoided or hoped away. When debt is unsustainable it will not be sustained. The only question is how and when the crisis comes. Here are the five options that can address the debt quagmire.

Option 1: Long-term debt reduction through budget surpluses

A key mistake of the Troika was to impose immediate fiscal retrenchment without articulating any long-term vision. It is well known (Buiter 1985) that it takes decades, not years, to use budget consolidation to reduce public debts once they have been allowed to rise to extremely high levels. If the Maastricht criterion of 60% is taken to represent a reasonable level – no one knows what is reasonable, but this is a side issue here – some countries such as Greece, Portugal, and Italy will probably need some 20 years or more to reach this level.

Moving from a deficit to a surplus is contractionary but remaining in surplus afterwards is not. This is why the costs of debt reduction are front-loaded and also why this is not the time to undertake these policies.

Of course, the longer it takes to start the process, the larger the debt and therefore the longer the debt retrenchment period afterwards. The resumption of growth is therefore a crucial precondition.

This would be the most desirable course of action if fiscal policy could be made temporarily expansionary, or if monetary policy could be used to kick-start the recovery, or if exports could lift the economy. Structural reforms are sometimes offered as an alternative but these policies take many years to produce their effects and are often contractionary at the outset.

Option 2: Sales of public assets

It would seem natural and easier for governments with large gross public debts to sell parts of their assets and use the proceeds to buy back bonds. This would reduce their exposure to volatile market sentiments and, ignoring implicit liabilities, hopefully demonstrate that their debt position is actually sustainable.

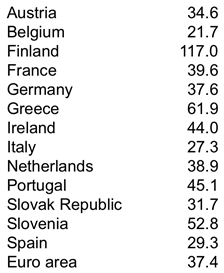

The problem is that we know little about the values of government assets. The OECD produces estimates of net debts, which can be used to recover estimates of assets (computed as gross less net public debts). The resulting estimates are shown in Table 1. For the Eurozone as a whole, government assets would amount to some 3% of GDP and most country estimates are found in the 30-45% range. Asset sales could bring indeed many gross debts down by significant amounts.

Whether that would be enough to remove the spectrum of defaults is impossible to assess.

Table 1. Estimated general government assets (% of GDP)

Source: Economic Outlook, OECD, June 2013.

Unfortunately, disposing of all government assets is neither possible nor desirable. In order to achieve its aims, a disposal of assets would have to be achieved in relatively short order, say two or three years. This would represent a massive administrative effort, probably beyond reach. It is also not desirable because it would resemble a fire sale.

Option 3: Classic debt restructuring

Under current conditions, the first two options are most likely to be unreachable, at least soon enough to avoid a continuation of the downward spiral that has gripped nearly all of the Eurozone. Rising public indebtedness naturally leads to a new phase of acute crisis. This will make debt restructuring not just unavoidable, but attractive.

The problem is that each country’s public debt has migrated to the books of its commercial banks. A debt restructuring deep enough to bring the debt to 60% of GDP is bound to trigger a bank crisis, which would require government intervention and more debt.

The much-maligned link between public debts and bank assets has become worse, enough maybe to make sovereign debt restructuring unmanageable without outside help.

Critically, many governments will need resources for bank recapitalisation following debt restructuring.

But the problem with bailouts is that they are no longer available in adequate quantity.

The main potential pool of money is the European Stability Mechanism, which is due to eventually reach a firepower of €500 billion. Compare this with the total debt of the crisis countries – Greece, Ireland, Portugal, Italy and Spain – which amounts to some €3750 billion. Add France, a likely candidate for crisis, and you reach €4710 billion. It is pretty clear that the resources of the European Stability Mechanism are nowhere near big enough to handle a series of debt consolidations.4

Option 4: Debt forgiveness

Even if additional resources could be found, outside help simply adds to public indebtedness and therefore makes the situation worse, not better.

A solution would be a two-step procedure:

• In the first step, the European Stability Mechanism or friendly governments could purchase large amounts of the existing stock of public bonds issued by crisis countries.

• In the second step, a Paris Club mechanism could be set up to forgive these debts.

In effect, this would be a transfer from the better-off countries to the crisis countries.

Plainly this option faces gigantic political hurdles. But the very size of task makes it economically impossible as well. A back of the envelope calculation should dissipate any doubt.

Suppose all the other Eurozone countries forgive a quarter of the debts of Greece, Ireland, Portugal, Italy, Spain and France. This represents a write-down for ‘forgiven’ countries’ debt that amounts to about €1200 billion. That is about 30% of the ‘forgiving’ countries’ GDPs.

To put this into perspective, a 30% jump in Ireland’s debt/GDP ratio pushed it from moderate debtor into crisis territory when it rescued its banks in 2010. If the ‘forgiving’ nations borrowed to cover these losses, Germany’s public debt would reach some 110% of GDP, but the Greek debt level would be only back to its pre-crisis level.

It is possible to have a Paris Club solution for a small country. This is in fact the most likely course of action for Greece. The drawback is that, once it is done for one country, it becomes irresistible for others. One may remember how Greece’s bailout in May 2010 was then presented as ‘unique and exceptional’, only to become the norm afterwards.

Option 5: Debt monetisation

As often when numbers become too big for governments, the central bank emerges as the lender of last resort. De Grauwe (2011) has made the crucial observation that the fundamental reason why the debt crisis has been circumscribed to the Eurozone is that the markets did not believe that the ECB was ready to backstop public debts.

The success of the ECB’s OMT programme so far, in spite of its conditional nature, shows the role that a central bank can play when it moves in the direction of accepting its role as a lender of last resort. But stabilising spreads is merely a temporary stopgap. The legacy of crippling and threatening public debts remains to be dealt with.

This is why debt monetisation emerges as another solution.5 But a mere purchase of bonds by the ECB will not work for two reasons:

• First, each country must pay interest on its bonds, including those held by the central bank.

These payments would go into the ECB’s profits to be paid back to its shareholders, i.e. to all member countries. As shown by De Grauwe and Ji (2013), this would be a transfer “in the wrong direction” from the country being “helped” to the “helping” countries. The only relief to a country would be through its own share of rebated payments.

• Second, when the debt matures, the country will have to pay back the principal

All in all, the relief is bound to be very limited.6

How the ECB Could Deal with the Debt

For debt monetisation to allow for relief, the debt must be somehow eliminated once it has been acquired by the ECB. One way of achieving this goal is as follows:

• First, the ECB buys bonds of a country, say for a value of €100.

• Second, it exchanges these bonds against a perpetual, interest-free loan of €100.

The loan will remain indefinitely as an asset on the book of the ECB but, in effect, it will never be paid back (unless the ECB is liquidated).

The counterpart of this operation will appear on the liability side of the ECB’s balance sheet as a €100 increase in the monetary base. This is the cost of the debt monetisation.

Debt monetisation has a bad reputation, which is justified by the fact that it has often led in the past to runaway inflation.

Under current conditions, this is most unlikely to be inflationary. Given the icy state of credit markets, increases in the money base do not translate into increases of the actual money supply; in effect, the money multiplier is about zero.

In addition, high unemployment has created a deflationary environment. But, hopefully, the credit market will be revived one day and the recession will come to an end. At this stage, the money base will have to be shrunk. This is the exit problem (Wyplosz 2013). An alternative is to raise reserve requirements to reduce the size of the money multiplier. Either way, the balance sheet expansion need not lead to inflation.

One solution is for the ECB to sterilise its entire bond buying under this programme by issuing its own debt instruments, leaving the size of the money base unchanged. This can be done at the time of bond purchases or later, when exit will be undertaken.

Of course, the ECB will have to pay interest on its debt instruments, which will reduce profits and seigniorage to all member countries, both the defaulting ones and the others. This transfer ‘in the right direction’ is the way all member countries will share the loss inherent to debt restructuring.7

As always, we have to accept the tyranny of numbers. Today’s balance sheet of the ECB amounts to €2430 billion. The big bang example examined above would add €1200 billion, an increase of 50%. This is huge, but not unprecedented. In July 2007, the ECB balance sheet was €1190 billion – half of what it is today.

Conclusion

At the end of the day, except for Option 1, which is the classic virtuous approach, and Option 2, the disposable of public assets, none of the other options is appealing.

But if Options 1 and 2 are impossible, one has to choose among bad options.

Option 3 is clearly the least desirable because it would shake the markets and possibly take down large segments of the banking system. Option 4 is not just politically explosive; it could trigger a debt crisis among the countries currently perceived as healthy. This leaves us with Option 5.

Of course, defaulting through the ECB is merely a fig leaf to hide the cost of debt restructuring. In addition to spreading the impact over the long run, it has the advantage that the non-virtuous countries will share the costs in the form of reduced profit transfers from the ECB over the long run.

Obviously, debt cancellation entails a huge moral hazard that needs to be dealt with. Here it bears to emphasise that bringing the crisis to an end requires two conceptually different actions:

• One is dealing with the legacy of unsustainable debts, which is what the options presented here do (note that it is proposed to deal with the debt stock legacy, not to finance on-going deficits. A once-for-all action is far less dangerous than a permanent moral hazard).

• The other is to make sure that it will never happen again.

This calls for the adoption of a rock-solid fiscal discipline framework. Solutions other than the ineffective Stability and Growth Pact exist, but this is not the topic of this article. The ECB must require that this be done, and done well, before stepping into the quagmire.

_________________

1 For an early analysis of bond spreads and the EZ (before debt became a crisis), see von Hagen, Schuknecht and Wolswijk 2009.

2 For an early call for an OMT-like programme, see De Grauwe and Yuemei Ji 2012.

3 For a detailed analysis, see Wyplosz (2011).

4 Smart defaults in the form of Brady bonds also require a lender with deep enough pockets.

5 Our proposal is quite distinct from deficit financing proposals (see Wood 2011, Bassone 2013). The distinction between stock purchases and flow financing is extremely important, both from a macro (inflation) and a moral hazard viewpoint. Indeed, a debt restructuring is finite by construction while debt financing is open-ended and potentiality unbounded.

6 None of this occurs in a country that has its own central bank.

7 The ECB debt instruments will in effect be Eurobonds, but with a crucial difference from existing proposals. Eurobond proposals only help the distressed countries by reducing the interest rates that they currently have to offer. Under the present scheme, the underlying national debts are de facto eliminated.

Please see original post for references

Please correct this typo:

“Option 2: Sales of pubic assets”

I’m fairly certain selling your pubic assets is illegal in most countries. Of course, this is Naked Capitalism, so hey, maybe anything goes…

Hah, for once that is not my typo! I copied and pasted that from VoxEU.

But maybe that is a Freudian typo. In some countries, the pubic assets might fetch more than the public assets.

A parallel between Europe’s debt problem and how to resolve it can be drawn with issues relating to growing levels of nuclear waste, and how this too should be dealt with.

As with both issues, our masters are determined to kick the can down the road – however, one thing is for sure as far as the debt issue is concerned, most of it will, and never can be paid back.

As we have witnessed in the UK, austerity has failed miserably to reduce our debt levels, both at a national and personal level – and whats the governments answer to this, why more debt of course!

Now I have nothing against ‘debt’, or Keynesian economic expansion based on growing government debt, I am against debt being utilised to blow another housing bubble as in the case of the UK.

When will these morons ever learn!!!!

As Warren Mosler or Bill Mitchell use to say, “With friends like that, who needs enemies?”

“Under current conditions, this is most unlikely to be inflationary. Given the icy state of credit markets, increases in the money base do not translate into increases of the actual money supply; in effect, the money multiplier is about zero.”

The money multiplier doesn’t exist, as banks don’t need reserves to make loans.

Yes, exactly. I wonder if we’ll see a blog response from Bill?

One thing I’ve suggested on a number comment sites is to instigate a Job Guarantee (MMT style) financed directly debt-free by ECB issuance. The idea being that if the unemployment & output gap is removed the debt becomes considerably more manageable. At least providing some breathing space – likely a few years – to then sort out a functional Euro system, or enable countries to leave without too much trauma.

But time has moved on & the situation has become worse, so where this might have been sufficient a few years ago, it may not be now.

An additional measure – again, as a crisis resoltution policy pending full reform of the Euro (or exits) – that could be used, is a per-capita debt relief ECB issuance. First proposed I believe by the Irish resident, much respected & sadly missed Feasta economist, the late Richard Douthwaite. The idea being that ECB issued grants be given on an equal per capita basis to cancel debt. Only if a person has no debt could the grant be then used for some other purpose. I’m not sure if Richard proposed an alternative application to government debt, but surely it could be applied to that as well as an alternative or even additional measure.

Of course, if retaining the Euro, eventually a system of destroying money, to head off inflation, as required, would need to be developed. ‘Functional finance’ of course, as proposed by MMT & some others.

From my perspective, living in (Euro) Ireland, it would be absurd & unthinkable to even start measuring the relative output, debt or ‘transfers’ between the counties or regions, let alone acting on that information in the beggar-thy-neighbour, race-to-the-bottom fashion of Euro authorities. We are one nation. End of story.

Unless & until the Euro system operates in similar vein & principle, my vote will be to exit the shared currency as soon as is practically possible.

I actually do think that the overall result, our prosperity & much besides, would be greatly enhanced by working together co-operatively with a common currency & taking solely a positive rather than punitive & negative approach to what are likely inherent productive value differences across the territory.

I see the public opinion aspect that media suggests is a barrier to this realisation as fundamentally a deliberate & contrived ‘denial’ of ‘macro’ economics itself. And I believe the reason for this is coming directly from from a selfish, greedy, ideology of elites & their ‘useful idiots’ who wish to deny virtually any public purpose role for Government, perhaps exccepting protection of property rights & of course ‘tax breaks’ for ‘business’. (A denial of democracy itself, by definition supposed to act in the interests of the majority.)

The glaring points of denial of ‘macro’ in respect of the Euro zone include such things as ignoring that one’s income is always someone else’s spending. The economy is a circular system – it is fatuous to pretend one part of the circle is more ‘virtuous’ than another in playing its part. Another is denial that any counter cyclical role is required at – & definitely not by governments. The entire Maastricht approach is to equate governments’ roles to that of just another private sector enterprise, just a different ‘product’. Surely a counter cyclical role by government – the only sector able to do it – is basic to macro economics as distinct from micro-with-bigger-numbers ?

Why is it that probably 90% – at least – of the general public (the electorate) have no clue whatever (nor have politicians!) what distinguishes macro from micro ?

How can meaningful democratic decisions on the economy be made with not just such disinformation, but information that is directly +opposite+ to the truth, as established by Keynes & others after the 1920s? (Truth in most aspects that no economist would dare deny for 50 years after that.)

Anyhow, I’ve rambled ;)

But the ‘can’ has only been kicked past the German elections in my opinion. Nothing is ‘fixed’. And don’t ask me what I think of Ireland’s sorry excuse for economists….or ‘media’ economics pundits….

Europe could ride this situation out just by modify how monetary policy is conducted so it isnt dependant on the lending whims of banks. Bypass the commercial banks and conduct policy directly between the CB and the people.

New stimulus will enter the system and be directed at paying off debt and demand will pick up.

God I wish there was no “Europe” concept – a Europe pre the so called modern sov debt market of the 19th century…

A Europe of the village and the market town.

Your articles should be more specific such as how the Rothschilds killed the French village stone dead – turning it into a tourist factory.

Do you remember a inn Ives ?

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ruob2YgbHwk

A nice technocratic article which, yet again, totally ignores reality and misses the point completely, as nice technocratic articles always do. It seems that technocrats are not mentally equipped to address reality, but only work with theoretical constructs inside their cavernous minds. The rest is history filled with failed IMF imposed torture that rips societies apart, called “rescue” and “economics”.

To make my point clear, the only tools the writers use to try and understand reality is bond buyer behaviour, Draghi’s proverbs, propaganda memes like the funny one that says that Greece was the one to bankrupt Cypriot banks and Cyprus itself and not Frankfurt which eliminated a competitor, wishful thinking that some sort of bold moves by glorious euro finance ministers will somehow solve the worst crisis in the history of humanity – which is partly their doing – in a heartbeat. Yet technocrats and ministers alike both fail to see that reality is elusive, stubborn and sticky and refuses to do as a bunch of apprentice magicians wish it to do.

Yet, at the very same moment that the writers publish their modest proposal using mental models and planning maneuvers on a piece of paper, people in the South lose their freedoms, their wealth, their private property, their culture and very soon their very lives by the millions, due to austerity turned one giant business opportunity. Well, let us contemplate on complex models and intra EU institutional schemes to solve this, shall we?

No dear writers, the only cure for the Eurozone is its fall. The cure will come on its own, in a form of a gigantic catastrophe, which will forever change the game and the world as we know it. The only real “cure” for Europe from this point on is the only thing it knows well and uses all the time: Brutal War. The solution is political, not economic as you may believe. And this is the article’s cardinal sin. It fails to recognize the very political reality of the crisis.

Although I do agree that the only way out is the collapse of the Eurozone, let us hope this can be done without war.

This collapse alone will bring about as much havoc as a war, without the million dead, at least not violently.

Au contraire, forming a genuine political union at this point would address these economic problems far more easily than just blowing up the economic union.

Everyone knows the original architects of the Eurozone foresaw, and predicted, that some monetary crisis of this sort was inevitable, and that such a crisis would force a United States of Europe to emerge or see the economic union collapse. It was a half-assed, partial, “this is as much as we can accomplish for now” union, totally lacking in political unity.

The economic union was supposed to stimulate and give birth to political union, once people got used to free trade and open borders and the Euro everywhere. Complete political union was always the logical next step, and it still is.

Now that the predicted crisis is here in full blown, member nations have to either get together and form a unified Federal government — or let Europe return to the viper’s nest of squabbling and warring little fiefdoms it was for millenia. That’s a very bloody past to look forward to.

It can be done. Call a Constitutional Convention, don’t leave the room until it’s all hammered out, and everybody signs the damn thing. All that stands in the way is piggish and stubborn fear of having to share anything with “those people” just across the border. And every member nation feels that way.

If the Eurozone does come apart, it’s only a matter of time before there is war, which is to say, economic competition by more forceful means. Here we go down that road again.

Whose turn is it to march into Poland this time? I forgets.

Unless the technocrats lording over the economic union abandon neoliberalism, the political union is DOA.

The crime of the Europeans was not to follow closely behind Bernancke and Geitner down Debauchery Avenue. That’s earned them a torrent of abuse from the Anglosphere press. The fear in London / New York is Europe will be better placed in future. Everyone is supposed to copy everyone else – this doing something slightly different is dangerous. It could be embarrassing.

I suppose the likelihood of systemic default is real and the possibility of a new Groat appearing – which this time really will be ‘as good as gold,’ promise – is high.

Have we learned anything? After several years of shock we are only today beginning to see some proposals for a really New World Order, one that we can all live with and enjoy. That’s where I will be focusing my gram of brain power and I’ll start with the American and French revolutionaries.

Whilst the IMF, ECB, Euro Commission and Bundesbank are not on my christmas card list – I certainly do not want Europe to revert to historical type in a outbreak of national wars once again.

We are already witnessing in the UK government sponsored assaults and moral panics against immigrants in general, and Eastern Europeans – this on top of their vilification of the poor, unemployed, elderly, sick and anyone not actually earning a six figure salary per annum.

I happen to like all the immigrants I know, together with the German’s and Pole’s – so no to neoliberal national wars – I’ll leave that to the yank’s – me, if we are to have any battles, I’ll turn up with a broken flower stuffed in the barrel of a vandalised rifle – twice in the 20th century nationalist wars have been fought, with the largest casualty being the working class itself – no more machine gun fodder – if the elites wish to fight, could they do it among themselves and leave us poor souls out of their evil machinations.

wonderful comment

Chris Rogers says:

For me, one of the most disturbing and pernicious trends we are seeing take place is the use of economics and other social sciences to morally condemn the “undeserving” classes you name, along with others.

This is a repeat of what we saw in the 1870 to 1945 period, a phenomenon brought about by the fact that “since the eighteenth century…the authority of God as a source of absolute truths of the world – the essence of the historic claim to authority of Jewish and Christian religion – has been superseded in many areas of society by the rise of science” (Robert H. Nelson, Economics as Religion).

As María Elena Martínez explains in Genealogical Fictions: Limpieza de Sangre, Religion, and Gender in Colonial Mexico, her book

The “rise of science” is very peculiar in that it has been anything but scientific and has about as much connection with what science is as the vapid bimbo in a cosmetic argument declaring ‘here’s the science bit’. Economics is little more than the claim ‘German technology for hair’. I’m thinking about Barthes’ description of a negro marine saluting the French flag.

I agree the fairly standard Critical Theorist critique of technology as ideology Mexico expands on here. The problem is that it’s a critique of a “science” that both is and is not. The crude assemblage of politics and economics laying claim to the magic of science is what is correctly under critique, but science practice is not understood as very different from this rot.

Both the recents posts on the EU are interesting, but share assumptions of political control fraud science in that the monetary system ‘must be’ the answer to our current blight conditions rather than the blight itself. Parasites are very skilled in presenting what they are not.

The presence of racism and sexism in our politics is shameful. One only has to think about the Balkans or Cyprus to know how dangerous – people turn back to the Barbaric temperament at the drop of the politically correct hat.

Michael Hudson has made the point that our technologies in production are massively improved often enough – making the obvious question why we can’t harness them to provide comfortable livings for all. The answer is we remain thoroughly non-modern in political-economic practice and morality.

The key component missing in analysis of what we might do in Europe on a monetary basis is transparency and why no one wants it given technology could do the job. My suspicion is they fear a cascade effect that would demonstrate no need for the current control system and the political-owner class.

So much is missing we can’t have reasonable discussion and one suspects this is the point. The gorey platitudes of ‘we must pay our way in the world’, PIIGS full of people dumber than ‘us’ incapable of controlling their kleptos, assertions to national pride (which nation has much to be proud of?) and ‘hard work’ as salvation – these are cheap and the technocrats bleed us through them. These people are not scientists – if enough people could do or learn science GOP/Tory and their Democrat/Labour shadows would be on the racist fringe where they belong.

Moral hazard aside?

Really?

You have not learned anything

No moral hazard — Then capitalism does not exist and criminals rule.

Doesn’t moral hazard apply as much to the lender making loans into a bubble as to the borrowers?

I agree with much of James Willson’s comment. The authors assume the sanctity of loans, but why should so much of Europe and Europe’s people destroy themselves so that Europe’s kleptocrats should be made whole?

Why not tax the hell out of the wealthy with income taxes, asset taxes, and estate taxes? No need to monetize anything, simply redistribute what they have looted from the people back to the people.

It is surprising too that none of the options include a euro exit. This is a more traditional approach. The new national currency is set one to one with the euro although if a country wanted to they could set their currency at a higher rate say to one X to two euros. All euro denominated debts are converted to the new regime, and then the currency is allowed to float, i.e. devalue and with it the loans. This can be a fairly chaotic process for a country but if a country is self-sufficient in the necessities it can come through this period fairly quickly and with its debts largely cleansed. Of course, in Europe, this would push the crisis back to where it belongs: on the Northern banks. Their recapitalization would not as now be accomplished at the expense of the peoples of the South. The question would be how the people of North Europe would wish to handle them. My advice is soak the rich whose greed created the crisis in Europe in the first place.

Note: In the article under Option 2, re the following “For the Eurozone as a whole, government assets would amount to some 3% of GDP and most country estimates are found in the 30-45% range”, that probably should read 30% in accordance with the following table, not 3%.

It does apply to every one.

And … if you include me in your “soak the rich” … I’m not going to lone you no money

Hugh says:

No, not in the world of moral depravity and hypocrisy inhabited by neoliberal gurus like Pâris and Wyplosz.

Did you catch their other moral decrees, for instance the one about “Option 1 [austerity]” which is the “classic virtuous approach”? Or the one about “the non-virtuous countries,” with its inherent racism and/or tribal nationalism floating only slightly beneath the surface?

This brings us to an interesting conundrum. If economics aspires to be a science, then should its practitioners even be in the business of making these moral proclamations? As Susan Neiman points out, Kant argued in Critique of Practical Reason that

So should science, as Einstein argued, not limit its scope to describing what is, instead of dictating what ought to be?

In Kant’s words, scientific knowledge is

Kant’s successors, however, “were not satisfied with Kant’s [and Einstein’s] orderly island of truth and set sail on Kant’s stormy seas in search of their true being.” (Michael Allen Gillespie, Nihilism Before Nietzsche). The “new brand of philosophers – Fichte, Schelling, Hegel – would scarcely have pleased Kant. Liberated by Kant from the old school of dogmatism and its sterile exercises, encouraged by him to indulge in speculative thinking, they actually took their cue from Descartes, went hunting for certainty, blurred once again the distinguishing line between thought and knowledge, and believed in all earnest that the results of their speculations possessed the same kind of validity as the results of cognitive processes” (Hannah Arendt, The Life of the Mind).

Which brings us to the current state of the “science” of economics,

faaaaak they could just print the money, buy the bonds and shred them

Nobody would know the difference. As long as the money paid for the bonds was used in ways that replaced the impaired assets associated with the bonds with better assets.

It occurred to me it’s like two gangs of lunatics fighting in the street. If somehow they all came to their senses, they could say “this is ridiculous, let’s just stop and go home”. They could do that, but the delusion keeps them fighting. The real issue is the nature of the delusion. the arms and legs can either fight or walk away and go home

The delusion is a real psychological phenomenon, but it’s not Newtonian in the sense of a velocity, mass, momentum and force. Instead, it can be instantly arrested with a 90 degree change of direction without violating any laws of physics. Because it isn’t physics, which is why economics is wall-to-wall nonsense with notions like velocity and units of something it calls “money”. These are only ideas and they can be instantly changed for better or worse, and how those ideas arise and change is the real reality. At first this all came to me as a joke, but the more I thought about it, the mmore I said to myself “Whoa! It’s really true.”

Consider that no matter how fast or slow GDP grows or how much debt or money there is, the size of the earth is the same and the trees and rocks are all the same. The only thing that changes is the nature of the cooperational structures by which people relate and that’s purely imagination.

In the meantime the various peoples of Europe must listen to guys Promoting Green technology who are sponsered by ” research grants from the Carnegie Corporation, Ford Foundation, and Rockefeller Foundation.”

What utter bollox

http://www.irisheconomy.ie/index.php/2013/08/01/green-industrial-policy/#comments

These guys credit engines produce scarcity through inflation & tax and then ask us to subsidize their new solutions….you could not make this stuff up.

A Hillare Belloc like skepticism of this debt clan is badly needed in Europe.

They and their system managers are running rings around us.

Spain went from being the no. 1 for renewables, world wind / solar energy guru, breaking several records. Sometimes topping Germany, a feat.

Today, Spain is taxing private households that use solar energy, to scotch competition vs. the State.

one link, this or similar was posted on NC before iirc,

http://www.sott.net/article/264544-Spain-privatizes-the-sun-by-levying-consumption-tax-on-solar-power

Renewables are an energy sink that can net some profit, provided cronyism, subsidies, mafia type moves, keep on giving.

All this has nothing to do with improving the energy mix or helping citizens or manufacturing, or any enterprise that requires energy, such as transport, agri, etc. It is just a grand scam, and Spain has shown that up.

How depressing. The EU can’t bury the debt forever because it does not have a central bank, it is only a joint stock company. To buy and “forgive” the debt will cost somebody @4.5Tr$ and probably won’t work? To do anything else just makes the debt worse? And none of this maneuvering would be necessary if the EU had a CB. They could shift to MMT policies, follow a sane budget, and forget the unbearable burden of modern public debt. So why can’t we? Oh, I forgot, we have a private central bank that is merely a cooperating agent with Treasury. And then there is the whole unaddressed question of private debt. We all need to go read David Graeber again. And Steve Keen. Somehow, it is debt as we have known it that needs to be abolished.

It is utterly depressing to read this- no one has learned anything it appears. The credit inflation allowed governments in Europe to “appear” to be fiscally responsible prior to the recession, while extending their own uncounted liabilities in multiple ways.

Shorter Yves: “But for recessions, no bad things would happen to government debt ratios.”

Good luck with that.

Yancey,

You need to go read Kalecki. Governments need to run deficits unless businessmen invest enough of household savings. The long standing historical evidence is that they don’t. Every time the US has cut federal spending, we’ve gotten a recession as a result and the debt to GDP ratio got worse as a result of the decline in GDP.

1. Governments aren’t a household. I don’t know how many times various folks here have said that.

2. It is undeniable that the blowout in government debt levels in Europe was the result of the crisis and bank sector bailouts. Go look at Ireland and Spain as prime examples. And no one was much worried about Italy (biggest government debt level in the Eurozone) because again prior to the crisis, pretty much all of its debt was held by Italian citizens

3. Government accounting treats all spending as spending, It does not create a balance sheet, showing what is going for transfers v. spending (stuff like the military or the EPA) versus investment (bridges, dams, the research R&D component of NIH spending). No one (well, maybe you) would object to “spending” that was an “investment” except we don’t account for it that way. And that’s just for starters.

England ran huge, sustained government deficits for over 100 years when its government debt averaged over 100% of GDP. That was also its period of highest growth. Would you tell me how this fits in your religious world view?

Please don’t impugn religion or at least not Christianity. Any Christian who understood banking (after nauseous puking at the corruptness of it) would hate it for it’s systematic oppression of the poor and welcome deficit spending as a source of debt-free* fiat to end the debt-slavery.

*Not now Calgacus or I’ll once again have to prove to you that debt-free fiat is possible.

Every time I read an article about the Eurozone I get this feeling of anxiety. I have had an idea running through my head for the past few weeks on a method that might be capable of extricating debtor Nations from this mess without causing any more harm to the citizenry of Europe and, hopefully satisfying the creditors. But I have yet to write it all down or figure out the whole process. Even so, I’d like to throw it out there and see what flaws or strengths it may hold…

The quick and short: Take Greece as the example. Run it on a dual currency. Drachmas for intra-national commerce and Euros for inter-national commerce. Run it on a conversion rate of say 1 euro = 10 drachmas. After an internal conversion of euros to drachmas you set up the future conversion like this. Every euro that is brought into Greece generates 10 drachmas. Every drachma leaving Greece is converted into euros. Note the difference between generate and convert. For example, a tourist comes to Greece with 100 euros, they go to a bank to exchange this for drachmas that can only be spent within the borders of Greece. The receive 1000 drachmas in return. The bank keeps the 100 euros, the euros did not turn in to drachmas, they made new drachmas. When the tourist leaves Greece, all their remaining drachmas are converted back into euros. So how ever much money was spent by the tourist remains in Greece as drachmas and the initial 100 euro (minus whatever wasn’t spent by the tourist) are kept at the bank. All euros kept in the bank must be spent to service the Greek debt load. This way the money used to pay down the debt is not directly tied with the money used to run the Greek economy.

I would be very interested to hear what anyone has to say about this idea. Like I said, this is a very short rendering of a not fully established idea, but one I’d like to put out there as an alternative to business as usual as relates to debt and creditors in the Eurozone.

The real solutions to our modern economic problems cannot be solved based on the terms that created them. We need to rethink what money is, what debt is, what government is for. Money was supposed to serve humanity, but now humanity is serving money. We have allowed our fictions to rule our reality. This must stop.

The apparatus of our enslavement is the tool of our liberation.

May all beings be happy.

A dual-currency system kills the *one* thing i personally still like about the euro: That i can pay with the same currency everywhere in my neighborhood without having to convert it (4 euro countries within 2 hours of my home town).

>All euros kept in the bank must be spent to service the Greek debt load.

Uh. So how can greece buy whatever it needs to make the tourist happy?

This will not work.

Besides: not all debt is equal.

>The apparatus of our enslavement is the tool of our liberation.

This is only true for weapons, and those make for bloody liberations.

Regards, Uwe

Hugh – “It is surprising too that none of the options include a euro exit. This is a more traditional approach. The new national currency is set one to one with the euro although if a country wanted to they could set their currency at a higher rate say to one X to two euros. All euro denominated debts are converted to the new regime, and then the currency is allowed to float, i.e. devalue and with it the loans. This can be a fairly chaotic process for a country but if a country is self-sufficient in the necessities it can come through this period fairly quickly and with its debts largely cleansed. Of course, in Europe, this would push the crisis back to where it belongs: on the Northern banks. Their recapitalization would not as now be accomplished at the expense of the peoples of the South. The question would be how the people of North Europe would wish to handle them. My advice is soak the rich whose greed created the crisis in Europe in the first place.”

Totally agree with you. Unless and until the rich are squeezed of their ill-gotten gains, this crap will continue to happen over and over again.

Most people just want to wipe the slate clean, as if somehow that solves anything. All that does for the elite is put a great big smile on their faces, as they crank it all back up AGAIN!

For every pull there is a push. The ultimate pressure and squeezing needs to be applied to the other side of the equation.

You want these Ponzis to end? Start pushing on them!

I love the description of options 1 and 2 as “virtuous.” So, according to Mr Paris, reduction or elimination of government services ( the key to realizing this is a neoliberal tract is the sanitizing of language. Budget cuts are rebranded as “budget surpluses”, or “fiscal consolidation”) is an ethical approach as is the fire sale of government assets to creditors. The author laments that these options, while desirable, are not possible so adoption of the least bad alternative is in order.

Oddly enough this represents progress. The Northern banks are desperately attempting to avoid an outcome they dread-a Eurozone exit by periphery nations or some other large scale debt repudiation by the South. This article attempts to find some solution between austerity, which is manifestly failing, and a massive debt jubilee which would wipe out the Northern Banks and bondholders.

I’m with Hugh. Put this back on the Northern banks who created the easy credit conditions in the first place.

I’m surprised that someone like Keen has not come out for soaking the rich of their theft rather than simply forgetting about the debt. Does he consider it more politically feasible to forget about it?

Another option is Steve Keen’s universal bailout with new fiat which he calls “A Modern Debt Jubilee.” This enables private debt to be repaid without disadvantaging non-debtors.

Of course the banks would attempt to blow another bubble once the economy recovers so outright limits on new credit creation would have to be imposed which Keen recommends. But I’ll go further and say that since government backed credit creation is THEFT we should take this opportunity to euthanize the banks.

Or not. In which case I wash my hands of this thieving world and cheerfully await the Second Coming, which I have some hope of surviving.

You shouldn’t have long to wait now, Mr. Beard. As the Gospels, written two thousand years ago, have assured you, soon. Very soon.

It’ll happen before you know it. Just have a little patience.

The favorite weapon of banksters for acquiring wealth and domination has been debt slavery, at least since Philip the Fair, although the argument has been made that it’s been going on since the Roman Republic.

You knew they weren’t going to stop with enslaving students and home buyers with debt. In the few short years since deregulation unleashed their terror, banksters are now back up to enslaving whole countries with debt. It was perfectly predictable, because that’s what they’ve always done. It’s what they’ve always said they would do.

Solution? An easy first step would be nationalize the banks that have become insolvent instead of bailing them out. Second, repudiate the debt resulting from fraud and prosecute the perpetrators. Third, reregulate the banksters.

Easy enough. But it won’t happen because the global political class has become hopelessly corrupt.

That’s the executive summary. Everything else is commentary.

Moral harard ?? Morals have nothing to do with. Debt restructuring or buring or what ever one would want to call it would mean that the elites IE bond holders, stock holders, bank owners etc. would take a major financial drubbing, which would be unacceptabvle to thos same elites.

Non of whome give a wet slap what it would mean to the common folk.

Exactly the same reason it was never considered here.

It should be obvious to anyone who has been conscious the last 40 years or so that thes eleites are completely berift of morals and ethics. Thart is why were are in this situation.

In the States we’ve never had the amazing government/public services most countries in Europe have. It isn’t necessarily right or wrong, but our government has never cares for us the way European governments shell out for their citizens. Hospital bills is a big reason why people go into debt in the first place. If you eliminated that, you’d have a lot less debt in this country.