We participated in a Room for Debate forum at the New York Times, on the topic of “Was Marx Right?” Readers are likely to say, “But of course!” Yet Marx had such a large opus and his forecasts were so bold that any fair reading has to come to more nuanced conclusion. But at least Marx is suddenly fashionable after many years of being The Economist Who Could Not Be Named.

The other participants were:

Doug Henwood, A Return to a World Marx Would Have Known

Michael Strain, Responsible Politics Can Cure Capitalism’s Ills

Tyler Cowen, Problems Are in Sectors, Not the System

Brad DeLong, Blind to the System’s Ingenuity and Ability to Reinvent

You can read our contribution, Foreseeing the Dangers but Not the Response, at the Times or further down in the post.

But I wanted to take the unusual step of taking issue with an small but crucial part of Doug Henwood’s post. And I hate making Henwood an object lesson, since I really like his work and the statement he makes is widely accepted as true. But it turns out it is more accurately seen as corporate propaganda that is widely accepted as true.

Here is the critical section of Henwood’s post:

How can this all be explained? The best way to start is by going back to the 1970s. Corporate profitability — which, as every Marxist schoolchild knows, is the motor of the system — had fallen sharply off its mid-1960s highs.

I recall Matt Stoller looked into this (using Fed Flow of Funds data) on his iPad when we were both at a Financial Times conference a few years ago and finding that corporate profit grew in the 1970s after they recovered from the nasty oil-shock recession of 1973-1974. That’s not inconsistent with my recollection of the business press as a young MBA in 1979 and 1980. Stock prices were terrible, and the business press was very critical of American companies, particularly American manufacturers.

But lousy stock prices didn’t mean lousy or falling profits. Here are some of the big reasons why the stock market was so depressed:

Inflation, inflation, inflation. Want to know why the Fed is so obsessed with containing inflation, to the extent that they are happy to hobble the economy?

High inflation means you discount future cash flows assuming the continuation of inflation. Those high discount rates mean future earnings are worth very little, which really hurts stock prices and other long-duration assets

High inflation also means investors can’t rely on financial statements. Asset values are in historical dollars, and understated. Depreciation is understated because it is based on historical asset values. That probably means companies are paying more than they should because the value of their depreciation tax shield has eroded. You can’t be sure of profit levels since it depends on whether you use LIFO (last in, first out) accounting, or FIFO (first in, first out). Investors do not like flying blind, so the “I can’t trust the financials” factor makes them even less keen about stocks.

American managers getting their lunch eaten by the Germans and increasingly the Japanese. Both countries were running better manufacturing operations and increasingly making better products. Some of this was by virtue of having newer plants (all post World War II), but much of it was due to being more innovative (for instance, Japanese just-in-time manufacturing) and better labor relations. American management was regularly depicted as sclerotic, and the managers themselves didn’t disagree that much with that assessment.

I asked Stoller to revisit his work and he obligingly put up a post:

I’m putting up this post at the request of Yves Smith. She tells me that the conventional story of the 1970s is that corporate profitability declined as foreign multinationals became competitive with US multinationals. Thus, so goes the story, there was a real impetus to cut labor costs.

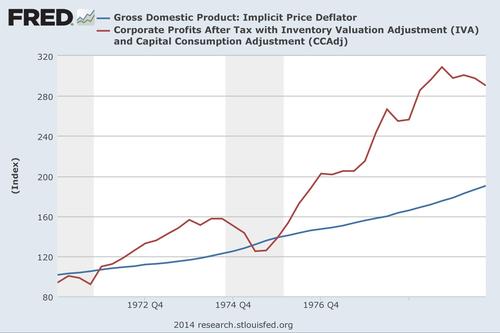

Now, I’m no wizard with economic data, so it’s quite possible I have this wrong. But It doesn’t look like corporate profits dropped. The story is more interesting than that. Here’s corporate profits against inflation.

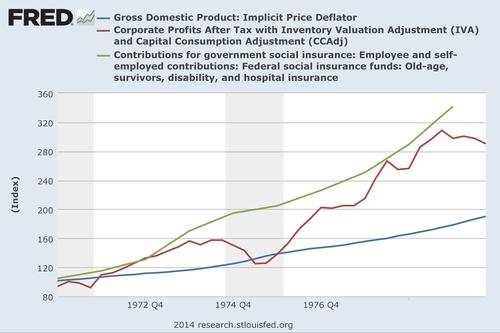

So why the story of lost profits? Well, these narratives serve a purpose, and in this case that narrative is organized around the idea that labor costs needed to go down. Where did the corporate sector get that idea? Well, what grew even faster than corporate profits in the 1970s? Social insurance costs. You see, in 1965, Lyndon Johnson implemented this program called Medicare, and that increased the amount that corporations had to pay to cover the medical costs of older people. And this cost stayed with the corporate sector even during recessions, because it was a labor cost.

Eventually, the corporate sector got a handle on these costs, probably by offshoring labor, breaking unions, and financializing. All three of these reduce social insurance contributions to the corporate sector. Check out the following graph.

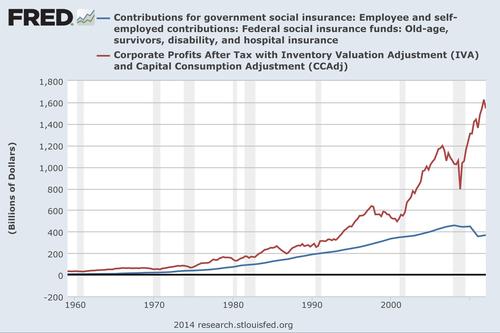

Today you can see there’s a massive difference between social insurance contributions (blue line) and corporate profits (red line), with roughly $1 in contributions for every $4 in corporate profits. Working your way backwards, there was a smaller yet significant bulge in the mid-2000s, a still smaller yet significant bulge in the mid-1990s, and a even smaller bulge in the early 1980s.

My sense is that this represents the corporate sector gradually shedding not just labor costs, but amount of profit generated by labor. That could mean financialization, increased monopolistic pricing power, offshoring, breaking unions, or all of the above.

Anyway, it’s an interesting phenomenon. Corporate America pays less in social insurance costs than it used to. That means that anyone who says that there used to be x number of workers for every y number of Social Security/Medicare recipients can be reminded that in the 1960s there used to be (roughly) one dollar of contribution to Social Security/Medicare for every two and a half dollars of corporate profits, whereas today there’s (roughly) one dollar of contribution to Social Security/Medicare for every

fivefour dollars of corporate profits.While there may be other ways to cut the data to come up with a story that conforms better with the official one, an inflation-adjusted look at corporate profits in the 1970s says they weren’t falling on a secular basis. The economy had a bad recession. But despite being mired in stagflation, corporate profits were still rising after the 1974-1975 downturn. Executives were no doubt frustrated by being faced with tougher-than-ever foreign competition, press that showed them little deference, and far less favorable domestic prospects than they’d enjoyed in the 1950s and 1960. But a more hostile environment is not at all the same as showing a profit decline.

Businessmen were overplaying their weakness at the time, to try to extract concessions from the government. As we recounted in ECONNED, the Carter Administration was desperate to do something, anything, to get the economy out of low gear. Business executives and lobbyists sold the Administration on the idea the the US was falling behind in innovation. But that was simply untrue if you looked at any objective measure, like patent filings. Carter’s science advisor nevertheless embraced the idea, while still calling it a “perceived innovation gap.”

And what was the remedy? Deregulation, natch, when regulation has been a major spur to innovation (air quality standards led to major improvements in automobiles, as well as changes in manufacturing facilities like paper mills).

So this would hardly be the first case where businesses sold themselves as being in more desperate shape than they were to win more concessions from government.

And now to our piece at the Times:

It’s important to remember that Marx was a journalist as well as a theorist, and, in contrast with most modern economists, started from empirical observation. Like Adam Smith, he decried the tendency of businessmen to collude to suppress wages, but his study of sweatshop conditions in industrializing Europe led him to take his conclusions much further.

The core of Marx’s analysis is that businessmen would eventually cannibalize their markets through overproduction, which would lead to declining profitability over time. Others, like Joseph Schumpeter, saw periodic crises of capitalism as inevitable, but Schumpeter argued that this upheaval was a matter of “creative destruction,” which his followers believe sets the stage for phoenix-like revivals.

By contrast, Marx believed that overproduction would lead to pressure on wages, which would prove to be ultimately self-defeating, since the drive to lower pay levels to restore and increase profit levels would wreck markets for goods and services. That’s very much in keeping with the dynamic in advanced economies today.

Marx’s forecast has proven correct by this weak recovery. U.S. companies’ profits account for the highest share of gross domestic product in the post-war era, while workers have gotten the lowest cut of G.D.P. growth ever recorded.

The relentless pursuit of lower labor costs by large corporations, which historically paid the highest wages, has helped push pay levels down, which in turn has resulted in weak demand and short job tenures. To the extent jobs have been created since the crisis, they’ve been concentrated at the bottom of the pay spectrum

Marx believed that industrial workers’ degraded conditions would set the stage for the violent overthrow of the system. That has not come to pass. The communist revolutions that did occur, in China and Russia, took place before major industrialization in those countries.

Marx failed to anticipate how the immense growth of commercial enterprises would create the need for a large range of managers, from shop supervisors and office managers to top executives, as well as technocratic experts such as accountants, lawyers, computer programmers and consultants. And while the Great Depression raised fears of radical revolt, the rise of large unions and Rooseveltian social safety nets served as a bulwark against the Red Menace. The well-paid union workers and the growing numbers of white collar employees created a new American middle class.

For more than a generation after World War II, corporations shared the benefits of productivity gains with workers, supporting demand, growth and social cohesion.

This willingness to reinvest in growth by keeping the middle class healthy is now seen in Corporate America as quaint altruism. Thomas Piketty, in his new book, “Capital in the Twenty-First Century,” makes clear that the experience of postwar America (and the rest of the developed world) was a historical anomaly. The more persistent trend, he found, was a rise in inequality when the rate of return on capital — the major source of income for the wealthiest — exceeded the economy’s overall growth rate.

A threat Marx downplayed has accelerated the concentration of wealth among the very richest. As Michael Hudson has noted, Marx recognized the destructive potential of financial capitalism, but thought it was inconceivable that it would become dominant. He believed the industrialists would succeed in keeping the bankers in check. They have not.

As income disparity has widened enormously and class mobility has eroded, Marx’s idea of class warfare seems particularly apt. But as long as there is a sufficiently large remnant of the American middle class, still socialized to identify with the established order, no matter how beleaguered they are, it’s hard to see how any organized, large scale uprising could occur.

Maybe I’m reading this wrong, but I think I found an inconsistency/typo in Stoller’s section:

Both can’t be right, right? And since it looks to me like the graph ends with Corp. profits just under 1600 and social ins. contributions at just under 400, it should be 1 to 4, not 1 to 5.

Also: blockquote SNAFU

I proof because I care…and because I’m up un-gawdly early with nothing else to do in the wee small hours of a Monday.

Fixed, thanks.

Keep in mind you are a fly-over person and Matt’s a Harvard man. Of course he’s right. Corporate profits are growing so fast from layoffs, unexpensed C-suite stock option grants and cost cutting they jumped while he was typing the sentences between the first and second references! Ya gotta keep your eye on the sky if ya wana fly.

Fly-overs give unfettered birds-eye views. From up there it seems that Marx wasn’t a Harvard man either, in fact, he was an autodidact. As impressive as the list of Harvard Alumni is (Yves Smith is at the top of that list), still it doesn’t seem as impressive as this one;

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_notable_autodidacts

Something to consider when debating the future of “higher education”.

I don’t see Adele on that list. If she’d gone to Harvard she might have gotten an MFA in Musicology and then a PhD and then a post-doctorate internship someplace while waiting tables at a coffee house. She could have been legitimate. It’s a tragedy. :)

Why does business pay for social security at all? Why make companies price their products and services to include these costs?

Speaking as a small business person I have railed against this. Speaking as a once employee, why was my insurance tied to my job?

The fact that the government has added so much cost to employees sets the back drop for companies to want to divest themselves of employees. And now that robots are taking jobs right and left, does it make any sense to continue to provide further incentive to jettison more employees?

Before buying that robot, remember that robots don’t buy your product. We keep reducing the size of the consumer class at the same time. That is the nature of a system. Unintended consequences result from too narrow a focus on a single subsystem. In this case wages, taken in isolation. Context in systems matter. Reducing wages has local and systemic impacts. Balance matters. Don’t undermine the social safety net at the same time you lower wages unless you want to create a larger underclass. Many people today never thought that they would fall into that underclass. Maybe, eventually, even you.

Very well said.

Kelman,

VERY well said.

Another view to look at it is that the economy is optimizing sub-processes (e.g. speculative finance) but sub-optimizing the end-to-end process (broad economic growth).

Anyone who has spend any time working has seen this issue repeatedly. I just never applied it on a country-wide basis.

We have to understand that policy of all kinds is made in on and ad hoc political basis. People in Washington do not think about how we can make things work better but, rather, how do we implement the contradictory orders coming from Congress and Congress listens to the contradictory political forces swirling around the Congress on a day-to-day basis.

No. Congress only listens to money.

And if our corporations had enough sense to cooperate instead of compete (the insurance industry against all corporations in this instance) we would have had single payer decades ago which would have given us all sorts of capitalist advantages. But heaven forbid we should ever have some sensible measure of socialism.

Sorry about that. I got confused. In the second instance, I was thinking about the amount of cash produced by corporations, of which some percentage went to social insurance taxes. In the first I was just thinking about the straight ratio.

I’ve corrected it.

I figured that was the case. 5 to 1 does sound better (for our side), but 4 to 1 is more intuitive from just looking at the graph.

Well since the topic is “Was Marx Right?” I will paraphrase Slavoj Zizek’s answer to the problem of “federal intervention”.

What you have identified as the “problem” (i.e. federal government tries to solve the problem of unemployment, retirement, crime etc… but it creates the problem by disrupting the market) is a necessary part of the “non-problematic” “normal” state of things that you desire. Without the problem (federal intervention) the market would have destroyed itself long ago because it is unable to create and maintain the desired “normal”(the “normal” of fair markets with fair pay, fair hours, insurance, retirement, legal protections, rules of commerce, etc…). There never was a “non-problematic” “normal” which existed prior to the problem you identified (i.e. federal intervention).

So although you are correct in saying “these solutions produce the problems they wish to resolve” you must realize that the “problem” is actually a solution to something else entirely. It is a solution to the following: “How can we get the market to produce a “normal” set of conditions that it would otherwise not produce? Because if we can’t do so the public will see the market as lacking, and reject it.”

A middle class socialized to identify with the established order and kept ignorant by a captured MSM and distracted by an endless supply of gadgetry, electronic media, cheap stuff, Hollywood, etc.

And I wonder, too, about the ongoing erosion of public education…keeping those at the bottom & middle stupid essentially (while simultaneously skimming public money into corporate coffers and destroying unions).

Combined, of course, with the plentiful circuses…

And of course the (effective) propaganda of the plutocracy and their handy parrot press re deficits, bad unions, terrorism, markets, etc etc etc. ( the public is socialized to identify with an established order that is actually shifting more and more against their interest with the vast majority unawares).

…A middle class socialized to identify with the established order and kept ignorant by a captured MSM and distracted by an endless supply of gadgetry, electronic media, cheap stuff, Hollywood, etc…

Ignorance and distraction is a mutual choice at some level.

As is allocation of personal resources to “gadgetry, electronic media, cheap stuff, Hollywood”. Isn’t engagement in the latter a demonstration that there is a large demographic that can still muster the financial resources by hook or by crook to throw it away on detritus? This Society has a long way to sink before it has fully wiggled itself into a corner and recognizes it’s state of denial.

The mother that had to give up, what was it dance and karate classes for the kids? The daughter is relegated to watching Beyoncé, or whomever the fck it was, on her 3G phone?? Are these the foot soldiers for a paradigm social change? Um try reading a fking book when the battery is dead?

I think the natural position of the middle class may be to identify with established order and be in many ways conservative not radical. Sure there’s almost endless decades of and ongoing propaganda. But I’m not sure it’s natural for the middle class to be radicals anyway, afterall they have something to lose – their comfortable lives afterall! Yes, I would tell them they need to put their sympathisies downward not upward, support Walmart strikers – as that is the LONG GAME and in their long term best interest as a class, but I’m not sure most of the middle class even can see it as in their short term best interest.

Sam Gindlin makes similar points in a recent issue of Jacobin:

https://www.jacobinmag.com/2014/03/underestimating-capital-overestimating-labor/

Was Max right? How do you lot know the name of my dog? He’s down for our pre-lunch walk, even though we haven’t put the clocks forward. Marx? That other old dog.

We might start by thinking of Cyrus the Great, the Persian who freed slaves about 500 BC or the Athenian Democracy we revere that did not. Moses in Numbers 31 is a vile war criminal, but some apologise for him as a ‘man of his times’. I’m not sure we can put the burden of being right on a man living in Victorian England. This was an England that abolished slavery and gave restitution to the – er – slavers. Karl was certainly more right in describing and condemning the squalor around him than scum ordering the Peterloo Massacre or Churchill in ordering striking miners be shot. He was more of a modern man than most around him.

I doubt he was making predictions about our current plight. He was right as a materialist, that material conditions affect pretty much everything. He was right following Hegel that having history gave us opportunities not merely to repeat it. Stronger views on laws of history are rightly dismissed as the poverty of historicism.

How might we judge him as an economist? Where is the successful economic theory from which we might judge? Was Newton right? Well not really in terms of what we know now. Theory generally lags the time at which we spotted the evidence in science by quite a long time. What we do in science looks something like the following:

Consider a theory T which is superseded by a better theory T′. One could use T′ in order to understand some of the successes and failures of T like looking back at Marx from today’s wonder-economics. If there is some systematic way of deriving T as an approximation within T′, then T is “reduced” to or by T′. In this case, T is successful where it is a good approximation to T′ and T′ is successful. On the other hand, in situations where T′ is still successful but T is a poor approximation to T′, T will fail. For example, classical mechanics should be obtained as the limiting case of relativistic mechanics for velocities small compared with the velocity of light. This would explain why classical mechanics was, and is still, successfully applied in the case of small velocities but fails for large (relative) velocities.

So can we reduce modern economics to Marxism in the special sense of reduction above?

Imprecision and non-uniqueness is crucial in the context of evolution of theories and the transition to new and “better” theories. Otherwise the new theory could in general not encompass the successful applications of the old theory. Consider for example the transition of Kepler’s theory of planetary motion to Newton’s and Einstein’s theories: Newtonian gravitation theory and general relativity replace the Kepler ellipses with more complicated curves. But these should still be consistent with the old astronomical observations, which is only possible if they don’t fit exactly into Kepler’s theory .

So what about the observations Marx was working with. Do we still have them to fit into today’s wonder-economics? We would be less concerned here with whether Marx was predicting what would happen now, and more with the observations of his time fitting the “more complicated curves” of modern wonder-economics theory.

I suspect the very question asked on ‘was Marx right’ as put in this post fails for structural reasons. In short and over-simplifying to the extreme, times have changed.

Was Marx right in the general sense? Utterly.

thoughtful comment…certainly makes sense. I generally hate these kind of things, ie was marx right…

room for debate is generally simplistic, silly, and brief…devoid of substantial debate, often with a far right POV spouting the usual memes absent of facts. the comments in response are often the best most informed part.

still, nice that Yves was included.

Human nature hasn’t changed. Marx saw the forms it produces more clearly than most. In fact, his perception of both quantity and form suggests to he wasn’t suffering too badly from RDS (Reality distortion syndrome), except I read once he lampooned compound interest since he lost his way in the power law distribution. If that’s true, it suggests to me his confusion over numeration means he wasn’t entirely RDS-free. But for an economist he did pretty well!

Without Newton, we would probably not had Einstein….

Newton was right on some things – others, not so much. Look at his work into alchemy and numerology (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Isaac_Newton%27s_occult_studies). Still, his work with physics and calculus makes him one of history’s most brilliant minds. I find it hard to get into his mindset without seeming anachronistic and projecting our current views and opinions.

Well, it might have been Newton’s interest in the occult (“as above, so below”) that prompted him to look for a single force that could account for the (legendary) fall of an apple and the motions of the planets. Inspiration can come from strange directions.

From Isaacs Newton’s Letters:

“If I have seen further it is by standing on the shoulders of giants…”

Ironically enough:

The earliest attribution of the phrase “standing on the shoulders of giants” is to Bernard (by John of Salisbury):

Bernard of Chartres used to say that we [the Moderns] are like dwarves perched on the shoulders of giants [the Ancients], and thus we are able to see more and farther than the latter. And this is not at all because of the acuteness of our sight or the stature of our body, but because we are carried aloft and elevated by the magnitude of the giants.[5]

There are rumours Newton was ribbing his great rival Hooke, who was a bit dwarfish. Of course, Newton, Einstein and Marx were just the guys who got the “patents of history”. We might well have the physics and social theory without them.

Yves writes, “The economy has left millions in despair, but if even a remnant of the middle class still identifies with the established order, major change is unlikely.”

Yes, but wait there’s more in my view. On the “Yes” side: the middle class only goes for big change if defines the prevailing order as inimical –for whatever reasons- to its survival. On the “But wait, there’s more!” side: social change is not an exclusive outcome of human agency. If we are at the limits to growth, as I believe we are, then human culture will change regardless of any human actions –by the 1% or the 99%- to prevent or guide it. A lot of nuance is omitted here. In short, nature is taking over.

Perhaps it might be better to asking if Henry George was right at this point in history.

There is the notion of ‘Hegelian Rabble’. Modern scholars on this write like postmodern text engines on speed. The gist is that we are all potential rabble now. Yves’ dire middle class, as seemingly unwilling to rebel as European peasantry over centuries, may become haunted by the thought of becoming part of this basic humanity with no place or recognition, and thus a new egalitarian politics could emerge from the fear of becoming nothingness. Typical authors include Agamben, Badiou, Rancière, and Žižek.

That is to say, under capitalism, everyone is at least potentially a member of this “part of no part,” exposed to the permanent risk of falling into the darkness of this state of internal exclusion (à la Jacques Lacan’s concept of “extimacy” qua inner or intimate exteriority). Related to this, insofar as the rabble is stripped of all distinguishing status symbols and denied social recognition within the hierarchized distribution of economic roles and political positions, it stands within modern societies for the zero-level of sheer, bare humanity.

That sort of stuff anyway. I have given up travelling in it and would rather sat it’s bloody obvious people don’t have to be poor. Doesn’t capitalism work rather like the above in reverse, motivating us by the threat we might become so?

I was working with brutal space constraints, so I could not unpack it more. Basically, the idea is that capitalism over time produced more class stratification, and members of each class is not inclined to identify/work at most with those in its own level. So squeezed members of the middle class who live in houses they can barely afford won’t work with McDonalds burger-flippers who live in single room occupancy hotels.

I followed the links Yves. There were 4 shorties worth ignoring, and yours.

You know, Marxism has a bad reputation, which gives Marx a bad reputation thus how others perceive you is also how they perceive what you say. The validity of what’s being said depends greatly on who’s saying it. You cannot educate someone who resents you. One would think that to alleviate common public misunderstandings the best course of action would be with honey & not vinegar.

http://www.isj.org.uk/?id=24

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-e8rt8RGjCM – quick run throughs of Marx applied to today.

Capital V3:part V contains Marx’s view on fictitious capital. He had the financial crisis of 1837-1839 to work on. Poynter, MacRory & Calcutt (2012) ‘London: a fictitious capital?’ (Routledge) compares the great man’s view of that with today’s farce, but sadly lapses into urban landscape stuff. They do note how reminiscent of today’s crisis his work is.

Marx said this of the 1837-9 crisis (p.470 of my copy from 1972)

‘An enormous quantity of these bills of exchange represents plain swindle …

(and) cannot be remedied by having some bank like the Bank of England, give to

all the swindlers the deficient capital by means of its paper and having it buy up

all the old depreciated commodities at their old values…everything here appears

distorted. Particularly in centres where the entire money business of the country

is concentrated, like London, does this distortion become apparent … it is less

so in centres of production.’

http://digamo.free.fr/perel87.pdf Perelman’s ‘Marx’s Crisis Theory’ – free pdf.

I don’t do much with figures now I don’t smoke (absence of the back of a fag packet). I’m sure we can’t do the right calculations to show Marx right or wrong in any case. Too much is missing, despite some compelling logic. Scarcity, Labour and Finance are only the start in a world of political manipulation. How could anyone from the 19th century know how long today’s adding machines could keep a financial fraud going?

Indeed. What we really have today is that economic/financial activity has replace war as a way to rape and pillage–same impulse with a different field of play. Ther eason for this is that our societies are very complex in structure which inhibits the most primitive of accumulations, i.,e pillage. Instead we have the most brilliant warriors in the world all competing and fighting. Marx had no way of knowing this, as you say.

I believe that you have a vast overestimation of the so called “brilliant warriors.”

First, I wish to congratulate Yves on her excellent essay in the Grey Lady. Second, a hat tip to – all of you. Great discussion. But please allow my sophomoric retort to the question of why it is we proles don’t revolt. Firstly, the U.S. remains a wealthy country. Even the lowly minimum-wage worker sees wealth around him. Now, this situation could make folks envious and resentful (I know I am), but the propaganda machine spews “land of opportunity” BS night and day. But there is more – and it is sinister. Slowly, Americans are becoming aware that non-conformity has a price, up to and including death. How many police murders of innocents that stood out, objected, or protested does it take? I recall that Ray McGovern an American patriot was beaten and bloodied for the mere crime of wearing an objectionable shirt, standing, and turning his back on Ms Clinton. This is intimidation, not just of Ray, but of us all. They control the cops, the military, homeland security, and much of the apparatus of intimidation. Hence, even if my life is being degraded by the elite and the capitalist system, I can still breathe. Hence, I share a concern that humanity is heading into a new Dark Age, not just here, but globally as the elite, primarily the financial elite, tighten their control on us all. I think that eventually this need for control will lead to a further reduction in education, particularly education in the humanities (which has already fallen quite a bit) and attacks on all systems of organized resistance, particularly the internet. Please note that many repressive regimes have taken control of what you can and cannot see on the internet. Don’t think it can happen here? Think again. And those who think for themselves, who question authority, will be painted as villains, bent on destroying social order (as conceived by the elite) and the dazed and confused proles would cheer their destruction.

Let’s hear it NC fans, is Chelsea Manning an American hero, or a criminal? How about Edward Snowden? Time is short. We are in a war, and few Americans seem to recognize who our enemies truly are.

Time is indeed very short.

This recent speech by Chris Hedges is one of the most realistic assessments of our current dire situation here in the U.S.. What makes it particularly chilling for me is that I know he’s making an effort to be as optimistic as possible here.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PeDYrKnLDi8

I am reminded of an essay that I believe was in the links last July, on the decline of jury duty:

Parenthetically, this is also something that played a role in the European witch persecutions of the 17th century: given that ordinary people could not prevent church persecution of members of their communities anyway, they took comfort from the fact that by not being selected and killed, which they took to ‘prove’ that they had the right kind of faith.

Yes a good comment.

Isn’t the fair comparison the case for which is worse, the corrupted economic model that Capital devolves into vs the corrupted model that Socialism devolves into?

We’ve run the full scale experiment of how the former can be run off the rails in this country, I suspect the only reason this debate exists is because the latter has not been full implemented and allowed to spoil.

Certainly what we have in this country is a system beaten-up so badly, strictly speaking it hardly resembles Capitalism, essentially in named only.

A more fair comparison would be our present Oligarchy v the form of Oligarchy Marxist Socialism would become.

Good point Opti. There’s loads of literature on how the essential freedom in Marx was totally screwed by the likes of Lenin – but the issue for me is leadership and how we control that. And how do we control any leaders when they can hide money from us? Mao’s daughter has $750 million and there’s a big corruption scandal in China – http://www.zerohedge.com/news/2014-03-30/china-confiscates-billions-ugliest-corruption-scandal-history

We need a rip-off proof society. I think it would help if we had job guarantee to force a competition for our labour. This said, we need some kind of protection from bottom-feeding free-riders too.

For a “rip-off proof” society, try a fool proof BitCoin. Make all money and money transactions electronic and publicly transparent. Bullet proof BitCoin or similar.

How could you hide rip-offs, outsize payments, illegal payments, etc when it’s all visible?

“proof” is never achievable in any complex system, no less a society. the objective should be rip -off tolerant.

There will always be an element in society that takes satisfaction in 0 contribution, the solution is being robust enough to carry the parasitic load rather than spending resources trying to totally eliminate.

Gabriel’s point is well made and it’s interesting we can’t do something this simple. We can work to degrees of tolerance Opti. I tend to want ‘revenge’ (perhaps) when my absolutism shows.

At DeLong’s blog, there is an excellent rejoinder by Marco Ross to DeLong’s contribution to that NYT debate.

http://equitablegrowth.org/2014/03/30/2443/over-at-the-new-york-times-room-for-debate-relevance-of-marx-monday-focus-march-312014

Marco Rossi, that is

Read that too Dan. I got the impression that the only contributor with an understanding of Marx not gleaned from the yellow press was Yves.

And with all due respect to Yves, that debate could have been titled: “Five Affluent White American Ivy League Graduates Discuss the Meaning of Marx in the New York Times.”

Uh, what exactly is wrong with that?

Would a modern-day Marx approve such a blatant attempt to sort and disqualify people by ethnicity?

Points taken and agreed. But even people like Foucault, arguing for ‘an insurrection of local knowledges’ are still ‘Foucault’, not we ‘peasants’ (not that we are even that now they’ve nicked our land). Viktor Labov said some interesting things on ‘Iyy League intelligence’ as compared with the real thing on the street. Still, with Mutt’s point in mind, I wouldn’t mind a reverse quota on the upper crust.

It’s a big, diverse world filled with people of varying insights and varying experiences. They all have very different perspectives on our contemporary economies and societies, and those perspectives are going to play a role in how and where they find Marx’s thought worthwhile – or not worthwhile. The provincial island narrowness the New York Times’s categories of people thought to have opinions that matter is a joke.

Since 2008 it’s become even more apparent than before that the socially moated outposts of smug and high-toned bourgeois bigotry – the New York Times, NPR, WaPo, the Atlantic, the New Republic – are a big part of the problem. They spend every day manufacturing and re-manufacturing the regressive, smooth-textured cruelty of the ruling elites and defending the machinery of exploitation and entrenched privilege from intellectual.

The elite rules by silencing.

I’m not an apologist for the Gray Lady, but for heaven’s sake — they are at least trying to get a more diverse group of opinions in the paper, and it seems that all I see in your comment is castigation.

For crying out loud – it can’t be easy or simple to try and take advantage of digital technologies and figure out a new business model while losing huge amounts of your traditional revenue.

I’m as pissed off at anyone at the NYT for their role leading up to Iraq, but it seems to me that they are at least trying to offer some wider perspectives, at least on economics. This set of opinions is on a topic they would not have entertained ten years ago. The glass is at least half full.

What on earth is achieved by sniping at the NYT for trying to improve itself?

I’m with Dan on this one. The NYT is better than UK serious newspapers, but the overall blandness and lack of wide, genuine opinion is truly despicable across the board. This is hardly the free press Marx called for.

Agreed.

Paolo Freire’s work here is helpful. In his seminal book, Pedagogies of the Oppressed, it is the job of scholar to meet people where they are at (in their own language) to transform consciousness around literacy, understanding how the masses play a part in their own oppression. Ultimately, this speaks to developing “organic” or local (Foucault) options and responses. I rather like how Chris Hedges goes to prisons to teach. Or how Diane Ravitch encourages parents to avoid standardized testing rituals.

Imo, I think this is precisely what made Occupy so dangerous. New language, tone and strategies that left 1% unprepared initially. The next movement, I hope, should be more chess than checkers.

DeLong’s essay was a pretentious shambles is which all DeLong does is pretentiously and confusingly deny that the ideas of Marx are in any way relevant to what we are observing about increasingly income and wealth inequality. Look at DeLong’s language, and notice that he treats readers as fools but New York Times readers understood.

Indeed. But I think he did use the word ‘grok’.

Cowen’s was the one that raised my ire – apparently, home-owning ‘middle class’ NIMBY’s like myself are the *real* culprits for our economic malaise! No mention of offshoring, tax havens, bogus accounting, or fraud — apparently those are not nearly as damaging to capitalism as NIMBYs like me (!) It’s me and my neighbors and our incessant demands that our local government try and be minimally competent in providing infrastructure and services that are the real problem of capitalism today. Oh, us and those evil, selfish, grasping first-grade public school teachers!

Words. Fail. Me.

This man has tenure?!

God help me.

Well, that’s it then TeaLeaves. Now you’ve associated us all with the Ist grade teachers, NSA will send the boys round. Surely, the private sector cavalry will come to our aid against these government monsters? Belay that hope of rescue, I’ve just heard NSA is the private sector cavalry.

Not to worry, ACO – those NSAer’s prolly had public school ejicashuns, so we can safely assume — given the rapaciousness of their former first and second grade evil, grasping teachers — that they cain’t do no readin’ ur writin’, an they cain’t add no numberz, either.

Which should mean none of ’em are competent enuff to do their jobz.

So we’re still safe 8^0

My good heavens, I wince to think that students pay good money to George Mason Univ to be taught that it’s evil NIMBYs (like me), and elementary school teachers (like a few of my friends, who happen to work their butts off) that are the true reasons that capitalism is rolling off the rails.

Well said Tea. The tales I could tell about some of the barking wuckfits I was once on faculty with. From blokes wearing women’s underwear and stockings under their trousers (vaguely acceptable), to the American idiot pronouncing the Lithuanian economy in fine shape owing to an increase in new vehicle registrations. The latter at least had the decency to throw up when I took him to see actual Lithuanians totting on garbage tips for a living.

On underwear (he was mad and a great lecturer), check if any is going missing. The Stasi used to steal and bottle that of their suspects, in order to give their dogs the scent. Or at least that was the excuse they gave.

“But as long as there is a sufficiently large remnant of the American middle class, still socialized to identify with the established order, no matter how beleaguered they are, it’s hard to see how any organized, large scale uprising could occur.”

One event you can add to the scenario which could end in an uprising is the effect of climate change on the insecurity of populations. The IPCC report says, “For example, the report discusses the risk associated with food insecurity due to more intense droughts, floods, and heat waves in a warmer world, especially for poorer countries.” ( http://www.theguardian.com/environment/climate-consensus-97-per-cent/2014/mar/31/ipcc-warns-climate-change-risks )

In the Atlantic provinces we have been having about two winter storms a week since the middle of March. If it stays this cold, we may not be planting gardens in mid-May (and I am not kidding!)

You’re absolutely right that massive food insecurity, experienced for the first time by the remnants of the middle class, would be a game changer in the U.S. and Canada. Yet do we have to wait for bio-collapse before we fight back against the kleptocracy? Our resistance to the vampire squid can be thought of more as a counter-revolution to the radical, extremist neoliberal destroyers of all that was decent in the old established order. I know that I’d see a return to Eisenhower rates of unionization, and corporate and wealthy contributions to meeting social needs through paying taxes, as an improvement. Of course we must insist on no backsliding from the social gains made by women, people of color, and other folks who were discriminated against in the ’50s and sixties. We also need to dismantle the oppressive surveillance state that has grown by leaps and bounds from the days of the Cold War. Fighting against the imposition of a radical new neoliberal, maybe even neo-feudal world order is not revolutionary– it is a matter of middle-class self-preservation.

Boasting every day of everything created through the will of the government… [this] press is constantly lying, since one day necessarily contradicts the other. And it reaches the point of not even being aware of its lies and losing all shame.

These people doubt of mankind in general, but canonise certain individuals. They sketch a repugnant picture of human nature but at the same time demand that we should fall on our knees before the holy images of a few privileged beings…

… a free press is the eye, always and everywhere wide open, of the people’s spirit, the expression of the confidence a people has in itself, the eloquent bond which connects the individual to the state and to the world… the shortcomings of a nation are equally the shortcomings of its press… [and]… it is precisely the freedom of the press that allows it to go beyond the narrow-mindedness of national particularism.

I’ve lost the citation, but the above is Marx. Before Marx came Hegel and he suggested that the economic and political dynamics resulting in poverty, itself functioning as a breeding ground for the rabble mentality, are inherent to the then-new political economies of modernity and the steadily widening gap between poverty and wealth under capitalism creates a corresponding rabble mentality in the rich, who come to believe that their gains contingently gotten through gambling on civil society’s free markets absolve them of duties and obligations vis-à-vis the public spheres of the polis,

In judging whether these now historical figures were right, I tend to think on what a reasonable person would say today. I’m rarely that sure of my own reasonableness, but I think the same as them now..

Great piece. Richard Wolff says that a glut in the labor market is what drove labor cost reductions and made resistance to them impossible in the period you discuss. Any thoughts?

The macro work I’ve done suggests there’s been a dramatic decline in the Job Offering Rate (JOR). The JOR is the number of jobs offered per corporate dollar in revenue and assets, time weighted to adjust for seasonality and one-time effects such as snowstorms. The labor market glut is a result of a declining JOR. Why would the JOR decline with corporate profits and cash going through the roof? This is where further research is needed. If somebody wants to fund it, send me the money and I’ll hire 7 assistants and we’ll figure it out, eventually. You can be part of the solution, not the problem. -Professor Tremens, NFL, GED

We here at the S.ociety U.nder C.ute K. ids E.mitting R.adiant S.miles feel that Professor Tremens’ important work is just the sort of thing we’d love to support with a multimillion dollar grant. Kindly mail the appropriate checking account and routing number we shall need for depositing the funds to: Ernie’s Mom’s Trailer, Lot 17B, 666 Forlorn Drive, Lackawanna, NY, 14218

Congratulations!!

But the candidate needs to pay a processing fee of $100,000 upfront, though.

Last night I was perusing the latest NYRB and read the review of Simon Head’s Mindless: Why Smarter Machines Are Making Dumber Humans. Relentlessly-advancing automatization of (nearly) all production and (most all) services means, basically, that there are too many people for too few jobs, and those few jobs have been reduced to mindless repetitive movements, with Amazon’s shipping facilities being the exemplar case. As the author and reviewer both note, human beings aren’t as efficient as robots at robot-type activities (they’re fractitious, they get bored, they have to be paid something, etc.), so the prospect for new jobs to replace the millions of jobs being lost through increasing automation just don’t look good at all. Even the once-thought-secure-middle management class is increasingly being subjected to automatized measurement of their output/productivity, and readers of the review (and I assume, the book itself) are left to infer that they too will eventually be outsourced to AI.

What will the 99% do when this point is reached? How will they continue living? Given that automation is global (though it’s still advancing at variable speeds throughout the world), at some point something will have to give–machines will be producing essentially everything, and no one will have any money to buy anything they produce. At least, that seems to me to be the logical and inevitable outcome of the current trend. The only thing left standing will be capital, which will be investing in … itself.

A series of climatic disasters would curtail the earth’s population, possibly severely, as would outbreaks of contagious diseases or global warfare. Is this the best our species as a whole can do? It sounds like something out of dystopian sci-fi, and yet…

Part of what we are seeing, IMVHO, is a profound failure of leadership – both corporate, as well as government. (There are exceptions, but overall, it’s a failure of leadership across the board.)

One of my friends has a lot of contacts with gerontologists, and if you saw the potential numbers of Alzheimer patients in the developing world in the next 20 years, your hair would catch fire. If you are a ghoul, invest in services related to supporting Alzheimer’s patients 8(

For both elderly and children, care requires performing tasks that only actual humans can do: washing, interacting, feeding, diapering, nurturing, care-giving. Yet our political and business leadership is not laying the basis for an economy in which there are a large number of jobs related to care-giving. We do not have an economy in which ‘humans taking care of other humans’ is economically rewarded, politically respected, and socially supported.

If you have the time to read the article by Hudson that Yves linked to, it’s clear that ‘usury capital’ has completely captured policy processes. (And for more on that topic, read the thread about Grayson cleaning Cokie Roberts’ clock ;-)

Usury capitalism contains an internal logic that strips assets, then when things implode, requires everyone else to bail it out. Cowering to that dynamic is, IMVHO, a symptom of failed leadership at all levels – from local, to state, to federal.

Other than Sen Elizabeth Warren, Alan Grayson, Sen Bernie Sanders, and precious few others, it’s hard to find people in positions of leadership who truly grasp the dynamics that usury capitalism creates – and the way that it destroys everything, including industrial capitalism.

My summary: Marx may be relevant, but to know why he’s relevant, one needs to read Yves, and then Michael Hudson. It becomes clear that Marx failed to foresee the dynamics of ‘finance capitalism’ (or ‘usury capitalism’) and his critique was consequently inadequate. But important, neverthless.

Marx did talk about the ‘roving cavaliers of credit’ – there’s a good article by Steve Keen here – http://www.debtdeflation.com/blogs/2009/01/31/therovingcavaliersofcredit/

“A high rate of interest can also indicate, as it did in 1857, that the country is undermined by the roving cavaliers of credit who can afford to pay a high interest because they pay it out of other people’s pockets (whereby, however, they help to determine the rate of interest for all), and meanwhile they live in grand style on anticipated profits. Simultaneously, precisely this can incidentally provide a very profitable business for manufacturers and others. Returns become wholly deceptive as a result of the loan system…“

Marx, Capital Volume III, Chapter 33, The medium of circulation in the credit system, pp. 544–45 [Progress Press]. http://www.marx.org/archive/marx/works/1894-c3/ch33.htm.

I haven’t read the relevant Smith or Hudson. The workers, of course, were supposed to win and prevent the clown banksters as the revolutionary proletariat dissolved itself into classless society. Marx did not provide the military strategy to achieve this.

It does look as if he knew about the finance dynamics of his own day. For that matter, humans have known a lot about debt and usury for a very long time , as Hudson points out somewhere. My own view is we neglect the biology of ‘screaming monkey economics’. Marx knew little science. Which would equip him well as an economist today.

Thanks, ACO – I’ll try to check those links later…

As for Marx and science, as Yves points out, unlike far too many (most?) other economists, he was trained to actually pay attention to things and observe closely. Hence, he saw what was in front of his eyes.

Empiricism tends to better describe reality than pure philosophizing can manage.

The Greenspans and neoliberals who theorize and indulge in mathematical fetishes lose touch with reality; Marx remained grounded in what he saw around him.

“As income disparity has widened enormously and class mobility has eroded, Marx’s idea of class warfare seems particularly apt. But as long as there is a sufficiently large remnant of the American middle class, still socialized to identify with the established order, no matter how beleaguered they are, it’s hard to see how any organized, large scale uprising could occur.”

An event on Sunday in Albuquerque, NM has me wondering – ongoing, peaceful, local protest which hardly had huge numbers but being very much in sync with general 59%disapproval of brutal police tactics did have that city disrupted for most of the day. Nothing to do with Marx and his economic theories, one might say, but very much in line with a linking of all influences intensively discussed on this good forum, and Marx is right there in the midst of it all.

This single ‘small’ event is, I believe, a sign of things to come – not massive uprisings of large numbers of people, such as we had protesting the Iraq war, when there was so very little media coverage. This country’s democracy was founded through small skirmish tactics by citizens, and that’s how I think change will finally come.

Congratulations on the excellent Times piece, Yves. There aren’t many economists today brave enough to invoke Marx, and certainly very few if any to raise the specter (pun intended) of class warfare. But I don’t share your pessimism regarding the potential for organization. In fact, the Internet provides a potentially very powerful tool for organizing (dare I say it) the Masses. It’s just that most Americans no longer see themselves as members of the working class. Obama has done a great job of misdirecting us to identify as “middle class,” which is absurd. Class consciousness is presently at a low ebb in this “every man for himself,” dog eat dog atmosphere.

But imo it is due for a revival. It’s just that things haven’t yet got quite bad enough. Be patient. They will.

I don’t think economic class solidarity is a durable foundation for long-term political commitment. Class solidarity is an opportunistic response to economic threats in the face of which some people are able to perceive a common interest. Thus, in the face of the economic crisis of the past few years, which was rooted in the financial system, all of those people who happen to be owner/creditors have an intensified interest in working together – and they clearly have. But the moral, spiritual and historic outlooks of people in the United States who have nothing in common other than a particular level of income and net worth, and maybe similar work conditions, are do diverse and divergent that hopes for them working together in anything other than a short-term coalition pressing certain reforms seems hard to imagine.

Agree with this. The deep rooted nature of individualism (most white males with privilege not wanting to being told what to do) cuts across income, SES, etc… And the collective nature of WITT (We’re In This Together) can be experienced by anyone who has experienced tragedy in the face of dwindling supports.

We need to think bigger to capture the American imagine in transition.

“Marx failed to anticipate how the immense growth of commercial enterprises would create the need for a large range of managers, from shop supervisors and office managers to top executives, as well as technocratic experts such as accountants, lawyers, computer programmers and consultants.”

Certainly some degree of specialization (e.g computer programmers, who have expertise that takes time to acquire, hold power because of tech expertise, other experts etc. plays a role: key point ppl can (or could, that power tends to erode..) become indispensable and thus command higher / decent wages or whatever.

However, beyond the core of highly specialist expertise, the managers, such as shop supervisors, etc. are in some sense superfluous. They are there simply because they go to where the money is, as in a certain system it is accepted that ‘bosses’, ‘controllers’ and ‘managers’ not to say jack-boots, are somehow required as the structure is, perforce, top-down, authoritarian (in some cases close to militaristic, see Amazon, etc.), and compliance has to be enforced.

All this costs Corps a huge amount but at the same time it protects their profits (perhaps in a misguided way, another structure might be more favorable to them), if only because (in their minds) it ensures that control remains at the top.

Without that pay-out, to the 20%, 25%, of hangers-on, i.e. not the 1% or even 10 but the 25 or so, let’s say, cadres in the régime, in the US that would be ‘top professionals doing a fantastic job’, in Ukraine, corrupt Oligarchs, just for the contrast…, the whole system would collapse.

The ‘labor value’ in terms of special expertise, or collaborative cadres within a certain society cum power structure, is not afaik discussed by Marx in the main writings. (No expert, me.) So Marx might be right, and irrelevant at the same time. Like many economists alive today.

That last bit of yours might hit the nail on the head Andrea. Marx could be right and irrelevant. I’d hardly use Darwin in evolutionary biology today, though tip my hat to the intellectual debt. The idea of Marx foreseeing the future is, in any case, preposterous.

Debt is evil for many reasons, but in the extreme, it is downright lethal. Add massive counterfeiting to the brew and you have an elixir so incredibly toxic that human beings find it absolutely irresistible.

“I recall Matt Stoller looked into this (using Fed Flow of Funds data) on his iPad when we were both at a Financial Times conference a few years ago and finding that corporate profit grew in the 1970s after they recovered from the nasty oil-shock recession of 1973-1974” – Yves

You recall correctly…

The graph below shows various metrics on a log scale so we can look at growth rates directly…

https://dl.dropboxusercontent.com/u/33741/Growth.png

The blue line is corporate profits. Looks like profits grew at one rate until around 1960, then took off at a higher rate from then on.

Also note that the “unprecedented spending” (green line) of the Obama Administration is well below historical trend, which has averaged 5% growth since WWII (not adjusted for inflation), and that spending growth fell off about 33% post 1980.

My take on Marx is very simple.

Marx happened to live at a time when the massive industrialization of Europe was just taking off. He saw that this industrialization promised huge surpluses. No dummy, he asked himself who’s going to grab most of these surpluses – the owners or the workers?

He put his money on the owners. Real easy bet. And in hindsight he was right.

After all these years, we still haven’t gotten that question down. As a matter of fact, we’re rolling toward the owners again.

Now it’s apparent that this arrangement is causing problems – but we don’t know what to do about it. The game is now tougher because the middle class, through their pension plans and investments, and of course the owners, both have skin in the game.

It’ll be interesting.

I don’t think you take Marx’s point far enough.

He bet on the owners of capital, but back in that period (mid 1800s), trademark, copyright, and intellectual property – and corporate rights – did not possess the power they have today.

Add on the fact that today’s ‘capital’ frequently takes the form of intellectual property and copyrighted content (software, entertainment, medical patents).

In addition, today’s ‘capital’ is often comprised of databases (like eCommerce, or insurance data) that actually generate new copies of themselves over time — and then they ‘create information about their information’ (i.e., they ‘informate’ by creating summaries or reports about their data). In other words, just like this blog, which becomes more valuable with each additional post, each additional good link, each additional good comment and tag, the value of capital now feeds upon itself, iteratively.

Marx did not foresee this.

He never could have foreseen this, as I’m pretty sure that he was not familiar with Maxwell’s work on electricity, and he could never have foreseen the implications of ‘digital, or electronic-based capital’ (software, telecom, data transmissions…).

Marx did not foresee that capital would one day, electronically, create new copies of itself, somewhat like the Sorcerer’s Apprentice calling up the many brooms. This is an exponential process.

Marx foresaw something linear.

What we have is exponential, and on steroids.

(FWIW, Hudson’s analysis is the only one that speaks to this problem of exponential growth outstripping the ability of the economy to produce real goods. Yves’ alludes to this, but none of the other NYT pieces mentioned this very big problem.)

Must stop lurking in here. I’m supposed to be prepping a lecture on ‘positivisms in marxism’ for this afternoon. Great to see a bit of informed debate though.

Maxwell is my dog, named after the great man. He is yet to discover electro-magnetism, though his nose tells me there are more things on this heaven and earth than philosophy that takes 40 years to tell us ‘trees have backs’ (Heidegger). Maxwell didn’t invent the computer. To blame him for this indiscretion seems a little like the ‘Marx got it wrong’ because he couldn’t see 100 years into the future freaks. Perhaps he drank his tea strained, thus losing the very futurology substances needed?

I’ll be talking about actual parasite mechanisms in biology this afternoon and asking people to model finance on this basis. This is a run up to the question ‘OK where’s the science in Marx then’ and oddly a BoE paper by Haldane that tries a model from biology. Participants will, of course, be subjected to the subliminal truth ‘blame the Nimbies’! Habermas is my favourite target for positivism in Marxism, as the old boy is so anti-science he is anti-positivist, confusing positivism with science. The logical positivists eventually discovered their anti-metaphysical stance was – er – metaphysical. Habermas thus emerges as positivist in his creation of positivist science as half-learning. This really doesn’t make any sense, but I’ll know no one is listening if no one takes me to task.

I’m fairly sure we over-face ourselves with theory. We’re being stiffed by thieves.

I suppose Marx did have access to information about the weird capital you rightly mention Tea. Various bubbles and tulip mania sort of stuff. I guess I really see the problem as our inability to recognise theft.

Best to your four-legged Max.

My recollection of Marx is that he was grappling with a new force in the world: e industrial capitalism, and its implications. The owners of machinery (i.e., capital) were going to get all the gains, and the rest of us have/had nothing to sell but our labor. He foresaw that the owners of capital were going to view labor as a ‘cost’ and squeeze it in order to secure (cream off, thieve) more profits for themselves. IIRC, Engels was the son of a Manchester capitalist, and thus had unique insight into this problem.

People tend to forget that Marx was living at a time when the US West was still being settled; I don’t think California was a state, and where I live (Seattle area) was still inhabited by Native Americans paddling around in longboats and living in longhouses. The Hudson Bay Co. had a settlement at ‘Fort Vancouver’ that was an offshoot of the fur trade, and the few students at the very first school spoke Chinook, Tillamook, and a variety of other Native languages. IIRC, Alaska was still the domain of Russia because ‘Seward’s Folly’ had not yet occurred.

London did not yet have sanitary sewers, and in the 1850s typhoid broke out in the neighborhood where Marx and his family lived. Typhoid was not understood – no one knew about pathogens until Pasteur, late in the 1800s. There is a terrific book called ‘The Ghost Map’, which explains that tea drinkers survived the typhoid because they: (1) boiled their water, thereby killing the pathogen, and (2) tea has natural properties that disarm the typhoid pathogen. The medical authorities of the day attributed typhoid to ‘stench’, and it was an iconoclast doctor who argued that something in the water was causing the deaths. He turned out to be correct. His case was supported by a young man who mapped out the deaths in Marx’s neighborhood, and realized they centered around a public pump.

The neoliberal economists of today are like those London medical authorities who believed that ‘stench’ was the cause of typhoid. Once they had an explanation that made sense to them and was internally consistent, they were impervious to all other evidence, and oblivious to any disconfirming information.

As for failing to recognize theft, I actually think it’s far worse than that.

We have been socialized to believe that the thieves are essential, smart, provide key services/benefits, and that we must all kowtow to them. However, I think post-2008, that illusion is weakening.

Hudson argues that Marx understood the mathematics of compound interest simply doesn’t work out; it outstrips the capacity of the economy to pay out, and inevitably collapses. Tulipmania just makes it collapse harder, and faster. Marx is still relevant in the sense that economic theories that fail to identify and deal with ‘rent extraction’ are doomed to fail.

Marx saw that (public) investment is productive in the sense that it creates the basis for more productive activity, whereas rent does not build capacity.

Lenin gave Marx a very, very bad name.

Neoliberals fail to adequately distinguish between rent and productive investment. Also, they confuse Marx with Lenin – who lived in the early 20th century, by which time London had sewers, California was a state, Alaska was part of the US, and industrial capitalism had reshaped the world.

I do not feel comfortable with these words, Beard might if he ever chex in again: bless; keep; love; speed… let there be no egregious sacrifices; maintain some balance of fairness; keep a long and detailed database of justice; and act or do not act but do so without without hesitation….

Seems the biggest thing Marx missed or as Engels pointed out – was the equity offering and subsequent voluntary or involuntary application of it.

Nor the ratchet effect modern “scientific economics” [idiom – (sociopolitical theory is the accurate nomenclature)] in its ability to circumvent a wide swath of moral and ethical questions by reductive logic and numerology, therefore shielding its self from from critical analysis outside the sinecures – it – establishes i.e. neoclassical, neoliberal, neo – Keynesian, AET, et al.

The aforementioned being nothing more than lobbying, marketing, PR, front groups for advancing the policy agenda of the most connected and powerful in society, securing their future in perpetuity at the cost of everything else.

Skippy…. equity – the sticky candy of the narcissistic pusher, humanity and life on the orb put in a fish-o-matic financial blender [derivatives up grade to mag rail (EMRG) snack food processor] .

Spot on Skippy. The Levellers came before Marx. All we really need to know is everyone could have a bigger slice. These days we’d have to qualify that, with ‘not of the stuff that is burning the planet’. Biologically, I suspect economics is no more than a sublimation of slavery as we can see it in animal evolution. They key bit is exploiting the energy of ‘someone else’.

Where might the revolution come from? The future is already with us, laughing at what it knws of our fossil record!

“Marx recognized the destructive potential of financial capitalism, but thought it was inconceivable that it would become dominant. He believed the industrialists would succeed in keeping the bankers in check. They have not.”

Marx probably didn’t foresee the full-on fiat monetary system that we have in the world today.

Z

Fundamentally, Marx was great at describing, poor at prescribing. Past cannot be prologue when a movement actively stands in opposition, which is why Marx’s historicism ultimately failed. Still, Neoliberalism– the movement that redefined the future of history and rendered Marx a poor prophet– has left the current system far more vulnerable to peaceful overthrow than anything Marx could have imagined. Can you see how? That’s the trick.

It really isn’t that hard. Good luck.

Thanks for sharing Scott. I’m leaving the planet too. I take it you have destroyed the blueprints to your space ship too? The secret is not to let the economists follow.

@allcoppedout,

You added a “t” to my name, which indicates a lack of reading comprehension, but that’s okay.

I’m not leaving the planet. I don’t have a space ship. I’m fighting, but I see no need to share openly when the opposition is clearly listening. Again, there is an active movement on the other side of this thing. Why telegraph what you are going to do when the other side takes it more seriously than “allies” like you do?

Seriously. Either you get it, or you don’t. You clearly don’t get it, but let me try to help you. The current paradigm only allows one way to exercise your power as an individual. Once you understand this, you have all you need to act. If you need more of a hint, go back and read Hayek’s The Constitution of Liberty again (for the first time?) and compare his conception of negative liberty to what we have today. This really isn’t that hard to do, you just have to have the stomach for reading Hayek, and I forgive you if you don’t. But if you manage it, all will be revealed. It really is out in the open for anybody who cares to look. No space ships. No blueprints. No smart asses. Okay, I went too far with that last sentence.

The sky is blue. The ocean is deep. Thinking for yourself can be really hard. This is how obvious what you don’t understand happens to be. Good luck.

I didn’t really think you capable of building a space ship Scot. Sorry about the extra T. At least it wasn’t a misplaced R. I wish I had more accurate dyslexia.

Hayek’s epistemology of tacit knowledge and rule following is flawed (Pleasants) and even in the Von Mises archive you might want to look at Hoppe (free) – http://www.mises.org/journals/rae/pdf/r71_3.pdf

Mate, you don’t get to think for yourself by adopting a ‘new bible’. Hoppe’s critique of Hayek is devastating, but leads to Von Mises and I could pull him apart. The more you read, the more confusing it can get, unless you can tolerate ambiguity well. We have known at least since the Pyrrhonists that many equally powerful arguments reaching different conclusions can usually be made. I preferred Popper’s critique of Marx and really, free thinkers today should be concerned with the current enemies of open society. I haven’t noticed that enemy in here.

Allc,

Or maybe put all bankers and financial people on the ship, send the ship off, then destroy the blueprints.

“A threat Marx downplayed has accelerated the concentration of wealth among the very richest. As Michael Hudson has noted, Marx recognized the destructive potential of financial capitalism, but thought it was inconceivable that it would become dominant. He believed the industrialists would succeed in keeping the bankers in check. They have not.”

Banksters and multinational corporations are working together to establish their dominance. This is globalization and Marx couldn’t have predict it to its final stage:

http://failedevolution.blogspot.gr/2013/12/an-imaginary-dialogue-between-bosses.html

There is a site, Michael Roberts Blog, “blogging from a marxist economist.”

He mentions the people who wrote in the N.Y. Times including Yves Smith:

“Marx blogged to death”

http://thenextrecession.wordpress.com/2014/03/31/marx-blogged-to-death/

I’d be curious what people think of it. (I’m no expert).