By Philip Pilkington, a London-based economist and member of the Political Economy Research Group at Kingston University. Originally published at his website, Fixing the Economists

This week the Scots will vote on independence and the ghost of Bonnie Prince Charlie will ride once more… oh no! I’m not going there! Living in London and being from a country that declared independence from the crown last century I have seen up close all the cultural demons that the run-up to the Scottish vote has stirred up. It is not very pretty.

History is a funny old thing. It is something that people generally take as something resembling Holy Writ but in reality it is something that is written and rewritten over and over again. Reading the newspaper commentary in the run-up to the Scottish vote on both sides of what may soon be a border is like watching this rewriting take place before one’s eyes. Old events are summoned up and old prejudices simmer to the surface. The starting point of historical rewriting — and historians do not properly appreciate this — resembles something between historical hermeneutics and schoolyard joshing.

Anyway, let’s try to focus on the economics, shall we? I could write an eloquent post giving my little interpretation of the forthcoming election. But that would just be my opinion — the opinion of an Irish-born London resident whose ancestor appears to have been an English Catholic who fled to Ireland after he lent his support to the Jacobite cause in 1715. Another little story floating on a sea of other stories, each of them individual myths that contribute to the push and pull of the politics of this country. Better to drain the sea completely and try to catch a glimpse of the seafloor that supports it.

Now, I have already presented my interpretation of the economics of independence in a paper that I published with the Levy Institute and gave to the SNP earlier this year. For an in depth view of the economic consequences of independence I suggest consulting this paper in full. Here is a very brief summary of the paper:

- The key problem for Scotland is that their export surplus and their government budget balance are tied to oil revenues.

- These revenues are volatile and any substantial deterioration would lead to a fall in tax revenues and exports.

- This means that any monetary framework must take into account the potentialities of these events otherwise it ties Scotland’s economic future to the volatility of the oil market — and to the sustainability of Scotland’s oil reserves.

And here is a brief summary of the consequences of this for various currency regimes:

- If the Scottish keep the sterling and if oil revenues fall a government budget deficit will open up. This will leave the fiscal position of Scotland in the hands of a Westminster government jilted by Scotland’s retreat from the union. Think: Eurozone but with more nationalistic bitterness.

- If the Scottish issue their own currency and oil revenues fall the current account will register a substantial deficit. This will put significant downward pressure on the new currency and could, in extremis, lead to a currency crisis.

Frances Coppola and others have said that Scotland should issue their own currency and then peg it to the sterling. This would simply lash the same constraints on Scotland as maintaining the currency union. They would not control their interest rate and they would be unable to run fiscal deficits without having the sufficient reserves of sterling to back them up. Coppola says (on Twitter) that this is the “least bad option”.

The reason Coppola makes the case for a peg is because she reckons that there will be very little demand for a Scottish pound. She writes:

North of the border, after independence, Scottish notes and sterling notes and coins would continue to circulate freely as competing currencies just as they currently do. But south of the border, Scottish notes would have much less value than they currently have – indeed they might be worthless everywhere except Scotland, just as the “Bristol pound” is worthless everywhere except Bristol. Only those who were doing business in Scotland or planning to travel there would want Scottish notes, and indeed as long as sterling was equally acceptable in Scotland, they might not bother with Scottish notes at all. So there would be a simply enormous exchange difference between Scottish notes and sterling.

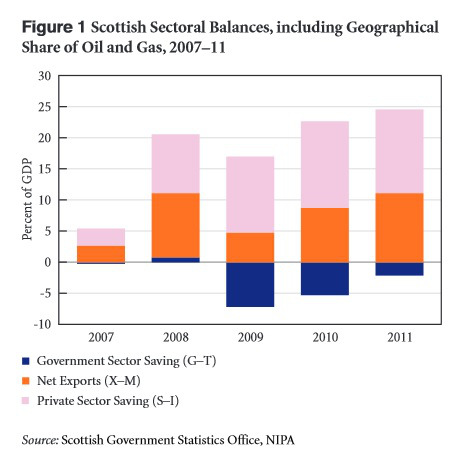

I don’t follow this reasoning. Scotland has a far more robust macroeconomy than the UK. Here is a graph from my Levy paper showing the sectoral balances of Scotland:

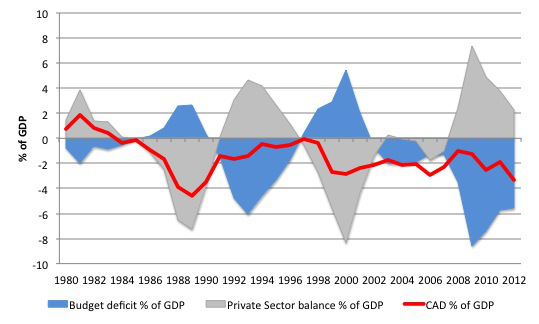

Compare that to the UK sectoral balances and you see a much more robust macroeconomy. Here are the UK sectoral balances:

The key variable that you should be looking at is the current account. Scotland has a persistent current account surplus which it achieves by exporting massive amounts of oil and gas (and food, but the oil and gas are key). The UK, meanwhile, has a persistent current account deficit.

Now, is someone seriously going to make the case to me that a country that runs export surpluses of 5-10% of GDP a year is going to have a weak currency vis-a-vis a country that runs trade deficits of 2-4% of GDP a year? That is a bizarre argument and I hope that no one would take it seriously. Importers from other countries will need massive amounts of Scots pounds to buy those exports from Scotland. That will generate huge demand for the currency. Investors will soon see this and rush into Scottish capital markets.

Coppola may, however, have a point about the short-run and I noted this in my Levy paper. In the short-run God knows how investors will react. This is where my proposal comes in. I will not lay out all the details here but only the ones relevant to this discussion.

My plan is two-phase. In the beginning Scotland will have a dual currency regime. It will maintain the sterling but at the same time issue Scots pounds at a local level. It will do this by paying part of local public sector workers’ salaries in Scots pounds and also accepting these Scots pounds in payment of local taxes (I am open to the idea of accepting these for payments of national taxes too). In addition, the Scottish government should enforce that businesses in Scotland price their goods in both currencies. Some post-nationalist slogan would do wonders in this regard — something like “Scottish prices for Scottish people”; on this front the SNP can consult what I can only guess are their legion of PR people and focus groups.

After a while, this will establish a stable exchange rate between the sterling and the Scots pound. The Scottish government can then gradually increase the amount of transactions it undertakes in Scots pounds — eventually only accepting Scots pounds for the payment of any and all taxes. As more and more of the Scottish economy transitions to the Scots pound, Scottish exporters will begin to demand Scots pounds for goods and services because they will not want to have to exchange their sterling for Scots pounds. This will generate external demand for the Scots pound and lead to the gradual creation of a sophisticated international market for the Scots pound. The Scottish government and central bank should be holding the hand of the market every step of the way as this embryo develops into a child and then gradually reaches adulthood, at which point it can be allowed go into the world alone, fully formed.

The whole plan is based around the simple notion that exchange rates should be established gradually. Scotland’s economic fundamentals — so long as oil revenues remain buoyant — allow for the hope of a highly valued currency. But it is still uncertain what would happen if they float this on the market in a potentially explosive instant. A gradual approach would allow the demand for the pound — driven at home by taxation and domestic transactions and abroad by exports — to be established over a couple of years. The peg would not allow for this as any removal of the peg would result in a once-off adjustment that would be uncertain and potentially chaotic. The dual currency approach is much more organic and gradualist.

With a floating exchange rate regime in place the Scottish economy will be well placed to deal with economic shocks. Should oil revenues begin to decline for any reason the Scots pound can fall in value to register the necessary fall in real living standards required. Again, the gradualness of the process is the key to stability. In the case of a fixed exchange rate — that is, a peg — this would possibly lead to a nasty fiscal-cum-currency crisis as foreign reserves dried up. A floating exchange rate still allows the Scottish central bank to use their reserves to prop the currency up. But by not establishing a price target it does not incentivise speculators to do what they do best: speculate (see: Black Wednesday).

Scotland could then focus on their key long-term economic problem: namely, their over-reliance on oil and gas revenues. This requires massive public investment projects in fields like green energy that will allow Scotland to continue to export large amounts of goods and services moving into the future. By formulating the correct answer to the currency question the Scots can face the real economic challenges; those that have to do with the production of salable goods and the scarcity of natural resources. By ignoring the problem and taking a haphazard, poorly thought through approach — or, what is the same: simply emulating what they think to have been ‘done before’ — they risk everything, in which case they should probably just give up the whole game.

Finally a note on the politics. Some people will say: “Sure Phil, sounds like a good plan. Well thought through and all that. But it is too new. It sounds like something that has never been tried before, no politician would go for it.” First of all, while the plan is original most of the key components have been tried before — and with great success, I have not chosen these components arbitrarily. Secondly, the SNP is about to dissolve a union that is over 300 years old. This is a massive step into an uncertain new world — one we rarely see in our rather boring and repetitive politics today — and to compare my currency plan with this is to compare apples to oranges. Or, to make the metaphor more fitting by comparing something familiar with something exotic, it is like comparing apples with Jamaican ackee fruit.

Interesting stuff but what’s all this rubbish about historians. Can I make a plea about his sort of rhetoric? Just concentrate on the economics…the ‘history’ stuff makes you sound like a literature professor.

Scotland needs to unglue themselves from Anglia rule. Once that is done they will have plenty of economic options going forward.

This seems to be an excellent plan to me.

From what I’ve heard,an independent currency has been looked at, but the advice was it would take around/up to ten years. This was seen as a bit too scary and hence they got into this mess.

However, if (jumbo size) there is the political will, this would be a good approach.

After all, who (including the loyal opposition) has held the westminster conservative coalition to any of their election manifesto?

I’m sorry, but this is the most ridiculous idea I have ever heard. Anyone with a current account (British English) or checking account (American English) knows that absolutely no bank anywhere widely offers a dual-currency facility. Some specialised products (aimed at expats, I had one when I worked abroad) allow dual-currency operation (e.g. USD/GBP, GBP/JPY) but these are incredibly clunky and cumbersome to manage in practice. And in the back office, they sit on specialised servicing platforms / infrastructure that is not designed to scale (they are niche products). And it still doesn’t solve the problem of who underwrites the currency risk. The account holder ? The bank ? The government ?

Only an economist could have come up with this one.

Philip, you’re an absolute treasure and I think your work is spiffing, but I’m wondering now, was that fog lapping across the Thames this morning, or was it something you were smoking ?

The Japanese, as you know, have massive retail currency trading, and as early as the 1980s offered all sorts of foreign-currency-related accounts. This seems on a practical level to involve precisely the same issues and risks. So why can’t that technology be tweaked for Phil’s application?

Oh, I’ve no doubt at all that it’s technically possible. I’ve used such facilities myself in the past. And we offer them (and a variety of remittance services which would be silimalrly useful) where I work. But it’s because of that personal experience and knowledge of what it entails to manage this sort of product that has me shuddering to think what would happen if these had to go mass-market. I’ll go through the main issues:

1) end user familiarity. Being brutal here, NC readers are a pretty savvy lot and would be well able to set the product up to run the way they need. Usually, you have to set a floor limit in the “checking” account portion of the product which is funded by an auto sweep from the “reserve” account (these two linked accounts are in difference currencies which is the essential feature of the facility). So the first step in the decision tree for the product user is “which currency gets assigned to which type of account ?”

Now, you’d presume that, at least initially, people would use sterling for the “reserve” account and the new Scottish currency for the “checking” portion. You should allocate the “local” currency to the “checking” account because that’s where you’d expect the bulk of day-to-day transactions to occur. But that presupposes a constantly-in-credit scanaio. What happens if you go overdrawn ? The product holder must be given the option whether they want to run up the debt denominated in settling or the new Scottish currency. The lender (the bank operating the product) can’t just foist a decision on the account holder. And how would the product holder make an informed choice ? At least initially, with the currencies operating (as proposed / conjectured in Phillip’s model) the differences and implications are not significant. But make the wrong choice and, over time, you can get pretty badly burned. I always seemed to be on the wrong side of currency volatility when I repatriated funds. It’s just a cost of doing business as an expat, but imagine the hoo-haa when it’s real people nursing real losses.

Actually, the same principle holds true on credit balances accumulated in the long term. Eventually, you have to make a permanent choice about which currency to use as a store of value. And sometimes, you don’t actually get a choice. A major asset purchase (your car conks out and you have to buy a new one then-and-there, your boiler croaks and you have to make a distress replacement) means you can end up crystallising your losses — losses which you might have been able to (quasi) “trade your way out of” if you’d had the luxury of time (to wait for the exchange rate to move back in your favour, whichever way that happened to be). Honestly, you’re turning the whole country into currency day traders (perhaps ending up having to trade on margin if they’re borrowing to fund essential expenses.) Not so much Mrs. Watanabe, more Mrs. MacAlastair.

Who is supposed to guide these novice ForEx newbies through the practicalities and implications of trying to manage this ? It will be the banks they turn to, who else is there ? And after all, the products are run by the banks and they can’t just evade responsibility — there are consumer protection measures in place (which I don’t suppose the new Scottish government would rescind) which require financial services providers to give rudimentary support to their customers.

Now, sympathy for banks is going to be in short supply (deservedly so) here on NC, but that loud sucking sound you’d hear if this proposal was implemented would be established TBTF players in the retail space retreating south of the border. Would anyone — seriously, as in, putting up their own money — want to operate in that sort of market ? I wouldn’t. Margins in retail banking are notoriously rubbish, but here it would be even worse — a complex product needing high-touch support to a mass of unskilled users. And the constant threat of lawsuits for giving the wrong advice. The compliance officer post of such a theoretical institution would be a hospital pass job. Another option would be to have a “post office” banking arrangement where the government assumed the risk of providing the product. And the costs, but I’ll gloss over that for now. Okay then, we’re going to start a new retail bank servicing 5.5M customers. From scratch. More likely, they’d have to nationalise an encumbrent player. Who hadn’t already beat a retreat down south. Which brings me on to 2)…

2) the ability to execute competently. The new combined currency account product would, by necessity, have a lot of options and more complex servicing needs than providers and users are used to. It may well, from the above, have to be operated by a new institution. Even if not, it would be new to the mass market for an existing institution. I am genuinely struggling to think of an example of competent, non-crappified, execution from any large scale institution in the modern era. They are all merely varying degrees of suck-iness. If anyone could make it work, it would be Japan. When I was there, it really didn’t. My sister, who still lives there, and I have a frequent running joke about her most recent experiences in trying to conduct business with a well-respected Japanese bank in two currencies. The problem is that it’s simply outside the range of normal procedures. There’s lots of deferential apologies, politeness and smiling, but not a great deal of actuall competence. In England (and Scotland too) we’d just get the incompetence with a side order of stropiness.

Savvy readers would also be able to spot the enticing opportunity for looting. Conversion between currencies gives a margin to the entity providing the conversion. It would take a tough and diligent regulator to prevent fleecing of customers through using wide spreads. Of course, the tighter the spread, the less profit, and the less enthusiasm for private capital to enter the market…

Sorry, I’d have loved the idea if I could, but I just can’t. Too many hours being apologised to and repeating myself on the phone has scarred me to the whole concept of this ever working out on the ground.

But you’re right of course Yves, you always are. My objections are based on risks which, even if they went bad, could nevertheless be worked out — given enough will on the part of the people who had to knock off the rough edges. In the end, this is all just about the will to do it (or not).

Wouldn’t most of this be solved by making the plan a little more radical – that is, Scottish pounds to be used for ALL domestic transactions, even while sterling is allowed for foreign ones? That way most people are dealing with only one currency, and so are smaller retail banks. As it is now in the States, there are only a couple of the larger banks that will do foreign exchange; I know my credit union won’t.

ATMs, on the other hand, handle foreign exchange very easily – they’re the best way to change money while abroad (as long as you can read the keys – I had a very funny experience in Morocco, because I couldn’t.) Couldn’t the same platform be used to handle a dual currency? The computer algorithms are already there.

Trying again:

1) Isn’t this an argument for being a little more radical? that is, they’d go directly to Scots pounds for DOMESTIC transactions (esp. taxes, as he suggests), but use sterling for international transactions. That way most people and most banks don’t have to deal with the exchange at all.

2) ATM’s are far and away the most efficient way to change money while abroad. They make the exchange, automatically, at current rates, in an instant. That means the platform is already there; why couldn’t it be available at the counter, as well?

Sorry – didn’t post right away.

At least this one is more concise.

Thanks for the post from Phil Pilkington; he is correct, as are you; it will take some time and adjustment to manage the currency transition. It’s easy to jump up and proclaim that it just won’t work. It will take patience and time. Scotland’s biggest challenge will be the transition to a currency not tied to the euro, nor the pound sterling. But it’s crucial for their success that they not be tied to the economic kite string of any other central bank. The Brits are sore losers and they have proved this throughout their history. Pilkington is correct in his observation regarding Westminster; they will do what is in their own best interest, not Scotland’s. All of that said, Scotland is positioned to take advantage of some huge natural resources that in time will wield even more dividends. If it chooses, Scotland can endeavor to transition to more green technology and be doing it out of a need for a diverse economy as well as being a world leader in sustainability through renewable energy production. For the moment though, the oil and gas resources will be the sustaining revenue source.

I’ve seen something like this at work in Tuscaloosa Alabama of all places, back in the ’90s. Tuscaloosa, a college town in West Central Alabama, has a large Latino population, primarily Mexican expats. When I worked there I used to shop in a Rincon, (small grocery store,) that had all prices in Dollars and Pesos. The cashiers took both currencies, and the exchange rate was posted on a board above the check out. I was told that there were three such multi currency grocery stores in the town. One of the unexpected byproducts of such a dual currency scheme will probably be a return of “hard” currency in one form or another. The Scots can gain great cachet by reintroducing monetary metal coinage to the ‘modern’ world.

People are living just fine with frequent flyer points, grocery loyalty, rewards programs and Bitcoins, so why not a parallel currency.

Plus it would show EU members how to exit the Euro gracefully. Anything with a possibility of doing that should be seriously considered.

An Oranges to Apples comparison (being generous, Oranges to Mandarins). Let’s take frequent flyer points — Airmiles for example. These are not traded on an exchange. They are a unit of fixed value. One air mile allows you to travel one mile on an airplane. When you “earn” one, that’s what it’s worth at the time of issue and that’s what it’s worth at the time of redemption. And you can redeem them any time at face value.

Interestingly, the scheme would only be viable (in its current form) in a low inflation environment.

Also, the T’s and C’s for the scheme includes a clause which, put simply, states that the scheme operates at the sole discretion of provider. They can withdraw it at any time, subject to reasonable notice (they’d have to give you, say, 12 months to redeem points at par). Try doing that with a sovereign currency.

I seem to remember Bank of Montreal (and probably other big Canadian banks) offering dual currency US/Can $ accounts, separate accounts in the specified currency when I lived there in the 1990s (hope to return soon).

Here in Washington DC, most tellers at the dreadful Bank of America (which I have sadly been unable to detach myself from) do not understand the concept that Canada has their own dollar currency.

Also perhaps this:

http://www.rbcdirectinvesting.com/us-dollar-plan/index.html

Hop on a berlin train to Szczecin (about 40 minutes) , everyone there is happy to take euros or zlotys, cash or card.

It’s all money after all.

I do seem to remember quite a lot of currency changes which happened comparatively quickly, all the eurozone, east germany prior to that.

Not quite a valid comparison. When I got to France or the Republic of Ireland, I take Euros. Some places, especially tourist spots, they take both, like you say. But they’re businesses who have made a commercial decision to withstand the costs and exchange rate risks of providing dual currency support. And they build that into their pricing.

Good for them, a sensible choice.

For Aunty Mable out in the highlands living on a state pension from a hypothetical Scottish government and an occupation pension from a pension fund who domiciled in England and trying to juggle the two, perhaps not so much.

How do all those expats in Spain manage with their pensions?

TD Bank.

I think it’s interesting to compare Scotland to another resource rich country, Libya.

Libya used its own currency to provide free education and medical care and to issue each young couple $50,000 in interest-free state loans. It also found $33 billion to build the GMMR (Great Man-Made River) project.

Interestingly one of the first things the rebels did was create a central bank to bring the country in line with the BIS which tends to do to national banking systems what the IMF does to national monetary regimes.

I think Scotland has the chance to go the opposite route of creating a central bank that serves its citizens. And it would seem the sooner the better.

http://truthout.org/libya-all-about-oil-or-all-about-banking/1302678000

Libya: All About Oil, or All About Banking?

Wednesday 13 April 2011

by: Ellen Brown, Truthout

If the “Yes” campaign wins, and the British banking establishment balks at easy cooperation (my idea of bloody-minded madness, but we’re talking about England’s financial predator class), Scots may find themselves having to adopt a tit-for-tat approach, rewarding every instance of British currency cooperation with a corresponding act of cooperation in return and, if that cooperation isn’t forthcoming, then, conversely, treating each intransigent British action on currency with a reply in kind.

Could the following, If all else fails, work? An independent Bank of Scotland resorts to a third currency–one the Bank of England cannot overwhelm easily–such as the Euro– or even the USD–to buffer their own incipient Scottish pounds in its early life, if that should have to come about. Thus, Scottish merchants would demand their trade with Britain be paid (by British customers) in the buffer currency while, within Scotland, those Euros are convertible to Scotland’s own national currency rather than GBP alone.

If there’s one really great thing to come out of the Scottish independence referendum, it’s that it has thrown into the bright sunlight (albeit briefly, although I hope it persists a lot longer) that, when it gets down to the real fundamentals, there’s no such thing as the nation state any more. It’s all largely about finance.

As Richard rightly reminded us yesterday http://www.nakedcapitalism.com/2014/09/scottish-independence-vote-views-from-distant-half-scot.html perhaps that’s the way it’s always been. It’s how Scotland ended up part of the union in the first place. But banks — and finance — are not and never will be ordinary enterprises. Hopefully more people are starting to realise, however dimly, there’s a lot more to them than that and they really should pay more attention to that man (or those men; and they are mostly men) behind the curtain.

Seven years into the worst economic depression since 1929 and we aren’t mindful of finance’s brutal potentials? I may not have properly grasped your point, however. Oh–having typed that, then re-read this,

“the Scottish independence referendum … has thrown into the bright sunlight that, when it gets down to the real fundamentals, there’s no such thing as the nation state any more. It’s all largely about finance”

Alright, I think I understand you–maybe. Wasn’t there actually not that very long ago at least a somewhat different and better state of economic and political affairs by which the finance and banking industries were indeed more closely scrutinized, more closely kept in check from operating with complete abandon? We’re the cycles of boom-and-bust fewer and farther between from, say, the very end of the Second World War up until about the late 1970s when high falutin’ financial theories came into vogue, and banks remade their image from staid old savings and loans to consumer investment supermarkets, with fancy glitzy marketing and hyperbole in sales and promotion? And, prior to that, wasn’t there an arguably firmer hand on the tiller by those in middle and high government office? Did we not see a rather significant decline in public confidence in public institutions as a consequence of the slippage from a flagging New Deal’s former robust character?

Am I to understand that for some reason, there is now no way back from the wandering path that Western so-called democracies have taken since FDR Truman were in office? That’s all now definitively finished? If so, what, in particular accounts for this stark before and after? And why would a populist bid for home rule in Scotland, rejecting the epitome of ugly, class-based austere inequality operated from Westminster and whipped upon the British provinces lying outside the golden circle of Londonian wealth be the symbol of that?

Still somewhat confused. It would seem to me that in Scotland, at least, what we’re witnessing is a greater appreciation among about half the public that the House’s tables aren’t not on the level and that the dice aren’t quite fairly balanced. That would tend to suggest a better appreciation for a fairer more democratic state, just in order that it not be allowed to be the case that ” It’s all largely about finance,” after all. The Scottish, whatever else they are, do not look like a people who at this moment are resigned, whipped and without hope for a change in the status quo. What else is to be understood by a groundswell of near-majority support to bust up a 300 year old political union?

What changed?

An important development, in my opinion, was the abolition, in many countries, of exchange controls. It seriously shifted the balance of power between governments on the one side and big corporates and the rich on the other.

Yes, that’s really captured the point I was trying to make too. If ever there was a time when nation states and finance were at least in balance, that time has long since past. The rot probably did set in with the abolition of exchange controls. While not by any means a perfect instrument, they did at least send a message: governments controlled capital, not the other way round.

I thought I was the only one left who still remembered / approved of them.

It stil makes feel ill when I contemplate what was done to the people of Libya

Yes, absolutely, the intentional destruction of a nation and society. For what purpose?

And the West is now doing the exact same thing to Syria and its people.

Looks like to me Scotland will have a “dynamic” euro like economy of exporting its surplus regardless.

If it devalues against English pounds more people down south can buy its goods and assets.

If the currency remains strong its ability to invest in efficiency measures will allow the English to buy surplus Scottish oil.

CH Douglas presented Scotland with a different solution some time ago in his DRAFT SOCIAL CREDIT SCHEME FOR SCOTLAND – see page 205.

http://douglassocialcredit.com/resources/resources/social_credit_by_ch_douglas.pdf

I’m curious about what others think concerning Andrew McKillop’s column at Ria Novosti. It’s entitled “Will the 300 Year Old UK and Pound Survive?” Here’s the concluding paragraph:

“It is sure and certain the SNP wants sterlingization or the continuation of using the GB pound, but if push comes to shove, they have other options. On several grounds, Dollarization may be the better of the quick and dirty options but an all-new, all-Scottish money cannot be ignored as a major and serious option enabling Scotland to negotiate with England from a position of strength over bank debt and national debt. These in fact are the key issues – the degree of sovereignty attaching to the liabilities of what are international private banks which, when they regularly get into the messes they create themselves, suddenly proclaim their national identity.”

http://en.ria.ru/authors/20140915/192961084/Will-the-300-Year-Old-UK-and-Pound-Survive.html

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5EMLOTsimSs

Please note: In the event of a “Yes” victory (*), I accept all–yes, all— “major currencies.” :^)

————–

(*) Equally, in the event of a “Better Together” victory. Good luck to a Free Scotland, Thursday and after.

Lots of smaller countries have their own currencies. We even have a country split off in a similar situation: Slovakia. They issued their own currency at par and then let it float and they did fine.

Slovakia went with a currency union at first, it lasted 38 days before they binned it. Both countries are still there as far as I can see.

From the discussion here, the seperation was carried out in far better faith than we can expect from westminster.

Just to note the price of oil is not important in this discussion.

Its who will have the purchasing power to buy it.

The English are using Scottish nationalism and their (previous) ability to create industrial stuff against them.

(The Edinburgh tram experience is not encouraging)

A scottish maoiist nationalistic drive towards overproduction will suit the English just nicely as everybody up north puts their shoulder to the wheel.

But who benefits ?????

The tram was/is a total joke but its history goes back to probably alistair darling’s era on the cooncil.

The first SNP government were against it, but being a minority administration, bargained it for the rest of their programme.

@Paul

We don’t really know what are good or bad investments as there is no real intrinsic domestic demand signal.

The function of present commerce seems to be to pay off a debt load to someone.

I have a affection for trams as a way of concentrating industrial output (rather then the diffuse nature of the transport Industry today , Industry is never effective when it is not concentrated)

The cars are most likely preventing distribution of capital to the human level……..but I could be wrong.

Anyway we seemed to be fixed on the notion that money works as a medium of exchange.

Its much more then that when used in industrial systems as machines don’t trade with each other in that fashion or any fashion for that matter.

Essentially the English have prefected the art of concentrating energy from the global hinterland (at great loss to local and recently national exchange)

We can clearly see this in the British physical trade figures , both finished machines and primary inputs are injected into the british system on a massive scale.

The British cannot use this effectively so essentially dump this surplus via the use of financial services , tourist activity etc etc.etc.

The loads of money chap drives to his “job” and therefore the capital gets extinguished in the driving.

I’m with you corky,

We used to have an excellent tram system, much like you can see on the continent. An older generation remembers it fondly.

They’ve got an old tram in a museum somewhere, a bit like marshall macluhans observations on horses as they were transitioned from draught animals to the entertainment sector.

I agree about redundancy capitalism, it is malign, pointless and destructive. It is however excellent at concentrating power, which is why we have it.

You’ll just have to forgive me for voting for something that might help make decision making a little more democratic than it is now.

Jaysus – given the previous deep masonic connections between Cork & Bristol you would think somebody in the city might have done something constructive.

I guess the reasons are deeper then the euro.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tgzQq6tJrtk&list=TL6Z_F05kWD7aMkR_hLjms2LcoKF6tCcmp

“Importers from other countries will need massive amounts of Scots pounds to buy those exports from Scotland”

I’m no expert here Phil, but given that Scottish exports are mainly oil and gas, and oil and gas are invoiced globally in USD, won’t the demand for Scottish currency be somewhat weaker than you suggest? Certainly, some of the USD earned by oil companies will end up being converted back into Scottish pounds so that they can meet their tax obligations (thus supporting the Scottish pound), but it seems a stretch to say that this will cause a fundamental divergence vis-a-vis the GBP. What’s your view on that?

Also it’s important to consider further “Dutch Disease” effects and other resource curse-like symptoms of being unusually dependent on oil exports. One classic remedy for the resource curse is heavy investment and attention paid to non-resource alternatives, which you mention, but which history shows tend to be very hard to implement, not least because resource dependence tends to kill off those very alternative sectors that you’re trying to foster, for Dutch Disease and other reasons. Setting up a Norwegian-style oil fund is another classic remedy. Hard to do in badly governed countries, where patronage politics militates against mustering the collective political will to restrain spending for the benefit of future generations, but in Scotland this would be easier to achieve, as in Norway – even though you’d have to deliberately invest outside Scotland in order to counteract Dutch Disease. That would obviously annoy a lot of people who want their oil money now, and require a lot of political heavy lifting. Just saying.

This sound very much like the merging of MMT with the idea of “complementary currencies” advocated by Bernard Lietaer. Lietaer calls for a transformation of our monetary systems away from currency hegemony which traps us in a world of scarcity and instability to the expansion of monetary systems to include multiple currencies, one of which is community currencies. There is absolutely no reason that a country such as Greece or Italy should not introduce a local “complementary currency” to address its social and infrastructure needs and give an opportunity for those that have been marginalized from an oppressive monetary system to contribute and participate. Lietaer says there are thousands of complementary currencies systems currently operating world wide. He says that access to the internet and inexpensive computing make this possible. Bitcoin is a case in point. Naysayers who say that the logistics of transacting in multiple currencies are just talking nonsense.

The USA was swamped with alternative currencies in the 19th C and it led to continual panics.

How about

http://voiceselsalvador.wordpress.com/2011/06/08/ten-years-later-the-impact-of-dollarization-in-el-salvador/

Hi Phil,

I think I should make it clear that I envisaged a peg to some other currency – not necessarily sterling – as a short-term expedient to stop the currency collapsing in the immediate aftermath of what could be a very difficult transition. I like dual currency systems though – I’m rather in favour of dual currrency as a solution to the Euro crisis, as someone further up this thread has suggested. The only reason I didn’t suggest it in this case was because I honestly didn’t think of it. Mea culpa.

However, I need to take issue with you on Scotland’s trade position. If we consider Scotland as if it were an independent country NOW – which is how the Scottish government looks at it when calculating its trade balance – then Scotland’s largest export sector by far is not oil, it is financial services. The assets of the financial sector in Scotland are something like 12x GDP, and exports of financial services (mainly to the UK) are 9% of GDP (15% of total exports). In this respect, therefore, the Scottish economy is dangerously unbalanced. This would probably resolve itself post-independence as the financial services sector is likely to re-domicile south of the border – indeed for the two largest banks this is a racing certainty, as the majority of their business is in England & Wales and regulators are likely to take a dim view of such enormous cross-border exposures for a small economy: we haven’t yet forgotten Iceland, Ireland and Cyprus. However, this means that there is zero chance of newly independent Scotland running a trade surplus. I estimate (following discussion with NIESR’s Angus Armstrong) that the loss of financial services exports would mean a trade deficit of around 7% of GDP. Additionally, about 30% of Scottish businesses are English owned, so investment income flows would be negative. Putting all of this together, unless ther is a vast increase in oil income post-independence Scotland is looking at a trade deficit that could be 10% of GDP.

Hi Frances, it’s nice to see you here.

Hi Clive! I do visit now and then – I just don’t comment much.

@Francis.

You don’t seriously regard financial services as anything like real goods.

You simply give somebody a load of money capital / oil to drive around in circles as he sells property or some other confuit asset and call it real trade.

This is the greatest lie of the British and soon English balance of payments.

The physical hole is much bigger then many think.

the main media meme of the last couple of days has been the ‘intimidation and threats’ of Yes voters by No voters. Precious little evidence is ever shown and still the story runs and runs, but I think that it’s a sign that the Yes camp some what desperate by shifting the story to ‘tone’ over ‘issues’.

Phillip, I thought your plan was even-keeled, and shows an understanding of how national currencies work.

In my opinion one the great failings of the modern materialist left (Neo-Keynesian/Heterodox/Marxist/Neo-marxist) is its continued failure to look closely at its own assumptions and the degree to which these assumptions offer insight or, as I believe in the case of potential Scottish independence, perhaps, misdirection.

For example, Phillip states “Anyway lets try to focus on the economics shall we?….Better to drain the sea completely and try to catch a glimpse of the seafloor that supports it.”

The implication of this perspective is that the seafloor (the economic base) posses more power to bring about effects or side effects than other spheres (culture, history, law, education etc.) that are forever condemned to the pathetic role of superstructure which somehow simply mirrors the base/seafloor.

Philip believes that the Scottish drive for greater monetary and fiscal sovereignty should not come at the expense of macroeconomic stability but it appears that it is the dreaded Scottish superstructure of culture and history that is the primary driver of this potential bid for national sovereignty with economic calculations and uncertainties being quite secondary.

Could it be that the assumption of an anti-idealist hierarchy of reality is not only obscuring they true dynamics of national self-determination but also clouding the capacity of leftist thinking to understand what is actually happening in the 21st century?

.

Will Old Frank of Tarbet Church, Loch Nevis swing it ???

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sAV8q4mnQ-I