Yves here. While the odds of commodities-triggered 2008 style meltdown is still not the most likely outcome, recall that that pessimists like yours truly assessed the likelihood of Seriously Bad Things Happening as of early 2008 at 20-30%, which I then saw as dangerously high. In other words, tail risks are bigger than they appear.

Some of the things that favor worse outcomes than one might otherwise anticipate is investor irrationality, or what one might politely call herd behavior. For instance, a major news story today was how investors are dumping emerging markets assets willy nilly, when many are not exposed to much if any blowback from lower commodity prices and quite a few are seen as net beneficiaries. The offset is that central banks have been conditioned to break glass and overreact when banks start looking wobbly. But the Fed may be slow to get the memo, since it sees recent data (the last jobs reports and retail sales data) as strong, and is also predisposed to see its medicine as working even though it is really working only for those at the top of the food chain.

Note that this report is from Monday in Australia, and look how much oil prices have dropped since then. WTI is now at $54.28 per Bloomberg.

By David Llewellyn-Smith, founding publisher and former editor-in-chief of The Diplomat magazine, now the Asia Pacific’s leading geo-politics website. Originally posted at MacroBusiness

Regular readers will know that I’ve been keeping tabs on the Loneliest Man at Davos, the Oliver Wyman analyst that in early 2011 predicted a second round GFC triggered by a commodity crash:

John picked up the phone. It was the bank’s legal counsel, Peter Thompson, calling. He had dramatic news. Garland Brothers, one of the world’s oldest banks, would declare bankruptcy tomorrow. As he lay there in his spacious air-conditioned bedroom, unable to return to sleep, John tried to reconstruct the events of the last four years…

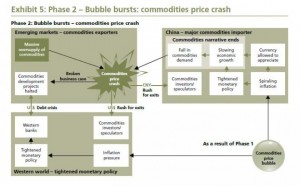

During phase 1 we distinguish between two sources of demand affecting commodities prices: demand for use in the production of other goods (“real” demand) and demand for the purpose of price speculation (“speculative” demand). There are three major groups of players in our scenario. Firstly, there are economies, such as Latin America, Africa, Russia, Canada and Australia, which are the largest commodities producers. Secondly, there is China, which is now the world’s largest commodity importer. Thirdly, there are the developed world economies, such as the US, which are pumping liquidity into the financial system through their loose monetary policies.

As with any bubble, our scenario contains a compelling narrative that allows investors to convince themselves that “this time is different”. In this case it is a story of strong economic growth coming from China creating a sustainable increase in demand for commodities.

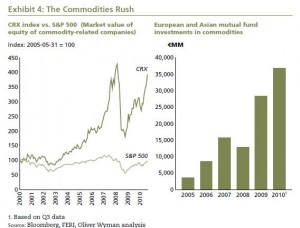

However, it is already apparent that increasing commodities prices are also creating inflationary pressure in China, which is exacerbated by China holding its currency artificially low by effectively pegging it to the US dollar. This makes commodities look like an attractive hedge against inflation for Chinese investors. The loose monetary policy in developed markets is similarly making commodities look attractive for Western investors. This “commodities rush” is demonstrated in the right-hand chart below, which shows the asset allocations of European and Asian investors. A recent investor survey by Barclays also found that 76% of investors predicted an even bigger inflow into commodities in 2011.

Based on the currently inflated commodity prices, commodity producers in countries such as Brazil and Russia have clear business cases for investing in projects to dig more commodities out of the ground. As competition to launch such projects increases, the costs of completing them also starts to rise, with the owners of mining equipment and laborers capitalizing on the increased demand by charging higher rates. Because a portion of the demand for the projects is not coming from the real economy, an excess supply of mining capacity and commodities will be created.

As with previous asset bubbles, we expect much of the debt financing for these projects to come from banks. And much of this bank financing is likely to be supplied by Western banks that are eager to preserve their diminishing return-on-equity and need to find lending opportunities that are sufficiently lucrative to cover their own increasing cost of funds. The balance sheets of life insurers will play a supporting role here, as insurers look for long-term investments that can match their liabilities and seek to earn additional illiquidity premia.

Well, that’s pretty much what happened.

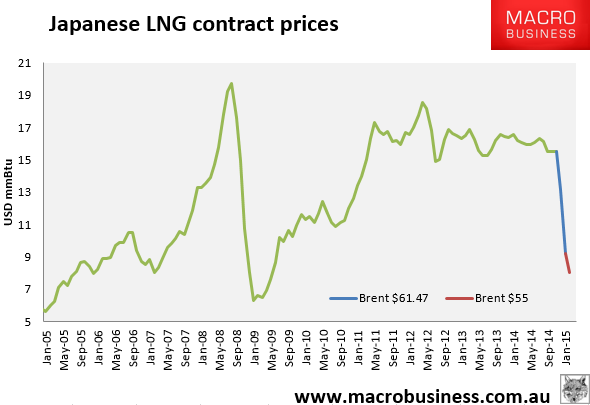

Now, switch to the present. Brent was down another 3% to $61.47 on Friday night:

Friday’s cause was a cut in 2015 demand estimates by the International Energy Agency, from the FT:

The IEA, the wealthy nations’ energy watchdog, said in its closely watched monthly report that global oil demand will grow by 900,000 barrels a day in 2015 — 230,000 b/d less than the prior month’s expectations — to 93.3m b/d.

Relentless US production combined with Opec output that exceeded estimates has coincided with a demand slowdown in China and a weak European economy, sending oil spiralling lower.

“It may well take some time for supply and demand to respond to the price rout,” said the IEA.

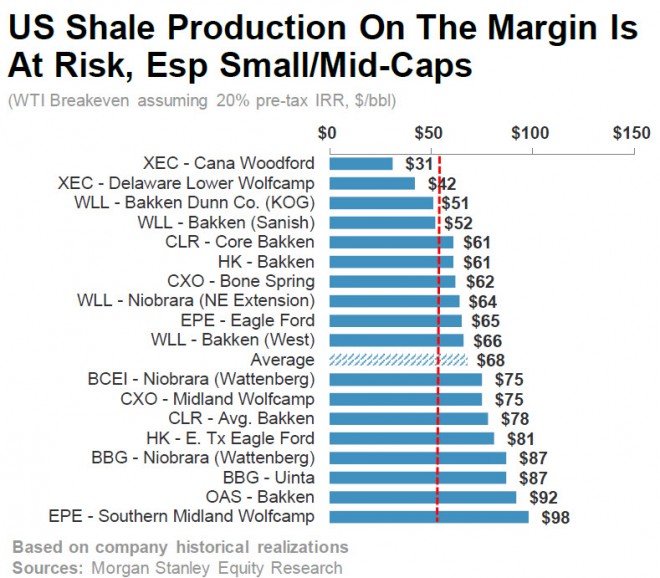

At this price (WTI $58), some 80% of US shale is uneconomic, according to Morgan Stanley:

Remember, though, that includes capital costs, which are sunk. The real marginal cost for existing wells is somewhere down around $20-30, once firms are restructured.

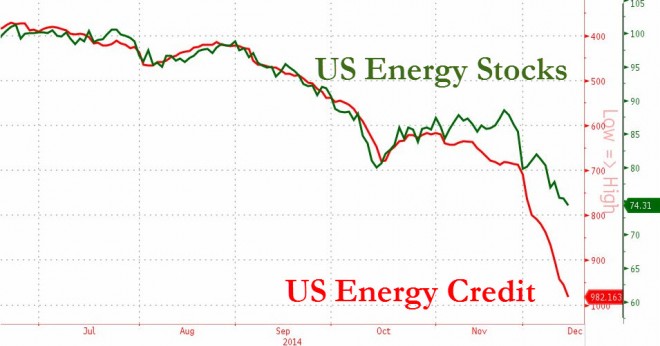

So, at this stage, rather than shutting wells, what we would expect to see is stress in shale debt and, voila, high yield energy bonds are more aflame by the day:

Back to the Loneliest Man at Davos, lets make some comparisons with the Global Financial Crisis. In late 2007, as US house prices were falling, debt markets began to shut for those that financed housing projects. The US Fed stood by expecting the housing market to clear without too much difficulty given sub-prime was a relatively small segment of the market. It considered sub-prime risks to be contained and, although it began cutting interest rates, risk was considered to have been healthily spread via derivatives.

What happened instead was that the risk had become opaque and filtered through to everyone and nobody, and as housing debt soured counter-parties to the debt began to wonder who held what. Trust progressively broke down, more lending was pulled, asset prices fell further, so on and so forth. The feedback loop ended in a virtual worldwide bank run.

The analogy with today is unsettling. The sub-prime market this time is US high yield energy debt. It is a relatively small segment of the US junk bond universe so the Fed is standing by actively considering rate hikes on the assumption that the shale market will clear relatively easily. They’ll probably be right.

However, the risks that shale debt is only the core of a rising bad debt problem for financial markets appears to be rising. The broader US corporate bond market is also seeing new selling, from the FT:

Investors are fleeing the US junk debt market as a sell-off that started in low-rated energy bonds last month has now spread to the broad corporate debt market amid fears of a spike in default rates.

The sharp drop in energy bond prices has helped push average yields on broad junk debt near the 7 per cent mark for the first time since June 2013, according to Barclays indices. The jump in yields come as redemptions from mutual funds and ETFs buying the securities more than doubled in the past week, to $1.9bn, according to Lipper.

…“The junk bond market is having a hard time and the pressure will continue,” said Michael Kastner, managing principal at Halyard Asset Management. “There are no real buyers right now and mutual funds will keep seeing redemptions.”

…Bankers, traders and regulators are concerned that strong buying over the past five years may be masking so-called “liquidity” issues in the vast corporate bond market that could come back to haunt them during a big sell-off.

The spread on Barclays US investment-grade corporate index has risen to 130 basis points, far surpassing its low of 97 bps reached in July this year and indicating weakness in the market.

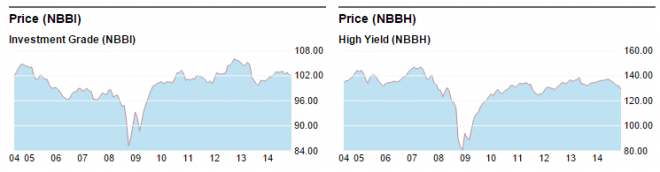

Here are the US high yield and investment grade bond markets:

Selling, yes, but so far contained in both markets.

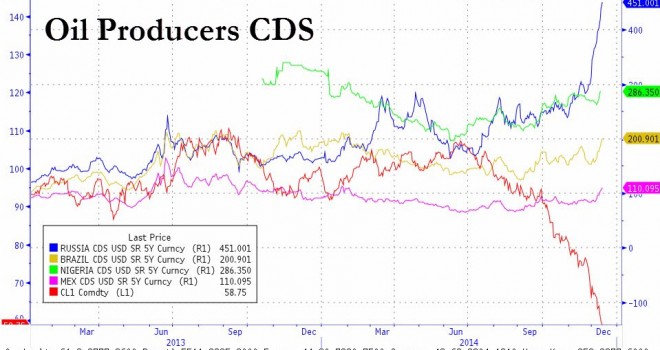

The other markets where contagion is more obvious are the oil producing states’ debt:

Other than Russia (and Venezuala), also contained so far.

We can draw a few conclusions, then:

• we are still in the early days of the shakeout and the blowout in spreads is so far small;

• as well, the falling oil price should still boost other parts of the global economy and markets and offset the damage done to oil producers, helping the oil price to stabilise via improved demand;

• but, there are parallels with GFC debt dynamics and having frozen once it’s easier for markets to do it again. At the end of the day, markets are made up of people and if the damage to oil-related debt is enough, it could reach a tipping point where fear and contagion runs out of control. This could take the form a “credit event” as a bank or big leveraged player in markets becomes insolvent on the rising bad debt;

• the Fed can end this quickly if it wants to, up to that tipping point, if it stands behind market liquidity with more QE, which will reassure that oil won’t fall too far and transform fear into reflation greed. The case for any early tightening in the US is gone. Right now I’d say market conditions suggest no bias to cut or to raise. Any move to renew QE will require much greater market chaos;

• the danger therefore is that, like 2007/8, the Fed does not move fast enough and oil-debt contagion gets out of control before it acts, dragging in banks that have loaned money to marginal oil plays and their sovereigns, a al the loneliest man in Davos. If that happens all bets are off with an oil-related debt freeze that would overtake the entire commodity complex and swiftly crush excess supply everywhere via a global recession.

Needless to say, Australia would not fare well in this final scenario. The major LNG projects that saved the nation from the GFC would suddenly be at the centre of renewed global crisis. Today, the LNG contract price estimate is at a new low of $9.19:

Far below breakeven for all of the seven recent projects and deeply in the red for the QLD three, which average around $12mmBtu breakevens. That includes the sunk cost of building the plants, so the marginal costs are more like $7-8mmBtu. If we get that low, gas export volumes will begin to fall.

If this shakeout really gets going, it is also fair to expect that the contracts underpinning the projects will come under intense pressure if not dissolve, exposing all to a falling spot price. We are already seeing some exit rumbles stuff from Sinpoec vis APLNG. It is unlikely that projects will stop producing given the marginal cost is around Brent $50-55 equivalent (and much lower for some of the cheaper gas), but changes in ownership at heavy discounts are very likely. On the upside, as global oil shakes out, the projects will have one huge advantage – they are built – so as debt and equity tighten, prospective competitors will disappear in droves.

It must be said that in the worst case, broader commodity debt would also be under such severe strain that the marginal players in all commodities would be at risk of simultaneous, catastrophic failure. Iron ore is the obvious candidate for accelerated and very serious fallout.

Without putting too fine a point on it, for Australia the scenario is a rerun of the 1890s depression, which followed the gold rush and Melbourne land boom driven by a proliferation of externally financed non-banks, culminating in a huge bust as offshore funding was cut off. This time around, Australian bank debt would seize up under the triptych of pressures of the general rise in global bank spreads, a sovereign rating downgrade as commodity tax income crashed and rising unemployment triggering falling house prices.

At this point a cycle that spins out of control in this way remains a tail risk, but there is no mistaking the structural change that is driving the commodity deflation and giving it a certain inevitability. We’re already well into shakeouts across much of the complex. The vital question is not if it gets worse but how fast does it do so? Will it happen at a pace that we can handle, as it has so far, and spread the pain over 5-10 years, allowing us to rebuild other non-resource tradables as a growth offset? Or, does it happen all at once, in a mighty cleansing?

As we end 2014, the answer to that question boils down to one more: is oil too-big-to-fail?

Because a portion of the demand for the projects is not coming from the real economy, an excess supply of mining capacity and commodities will be created.

Yes, this is absolutely critical and I’m glad to see someone drawing attention to it: speculation in commodities encourages overinvestment and, if sustained long enough, can generate pressure for a deflationary slump whenever the money moves on. And it always moves on. Traders eventually sell what they’ve got for something different, it’s the way of the world.

A perhaps naïve question, but since I’m constantly amazed at the irrationality of markets I have to ask: has so much liquidity in the form of QE, ZIRP, and derivatives been created that money can keep pouring into something like the shale oil industry even though it makes no money? When does the well of credit run dry when so much nominal “money” is sloshing about the world capitalist system? Can the system keep throwing money at this, the way it has Amazon.com, in some kind of massive potlatch ceremony, indefinitely? Since there is no longer much connection between how much money is out there and how many goods and services are being produced (derivatives alone I’ve heard have a nominal value dozens of times the entire global GNP) can the capitalists keep this ball in the air (with clever management) indefinitely?

Part of the issue is shale companies have debt to service, either in the form of junk bonds or bank loans. I am pretty sure these loans are bullets and don’t amortize.

So their incentive is to keep pumping to generate cash to make interest payments even at a loss and hope things turn around sooner rather than later. My understand is some (many?) have open lines of credit, so they basically borrow more to keep the loans looking current. And if they are in real duress, they can hold off other bills more readily than they can hold off their money sources.

Yves,

What do you mean by “these loans are bullets and don’t amortize”?

Is it that these loans are more “deadly”?

Why can’t bank loans be amortized?

Thanks for any illumunation. . .

@thecatsaid.

I believe it means the terms of most loans do not require amortized payment but complete return of the loan on maturity. In effect they are interest only for the duration and hence the servicing payments are lower till maturity.

From the few 10k’s I have seen this is so and furthermore some loans have a PIK feature (payment in kind) whereby the interest is serviced by automatically creating further loans representing interest stream thereby masking the lack of adequate cash-flows till maturity.

“Why can’t bank loans be amortized?”

The loan terms don’t require it.

Of course a long time ago some loans required creation of sinking funds whereby cash used to set aside periodically even if no amortization was directly required but we are an aeon from those days.

Veteran wildcatter is advising shale rookies to take cover. Speaking as someone who grew up in the middle of the 80’s boom and bust (Permian Basin), this is looking way too familiar for comfort.

http://www.bloomberg.com/news/2014-12-15/oil-bust-veterans-brace-while-shale-boom-newbies-swagger.html?hootPostID=c391e6dc33ac21cda6a319d232d92263

I was there too at the time, working for Schlumberger in Monahans, I recall the rapidity of the contraction in oilfield activity and have been wondering if something similar isn’t brewing right now.

Biggest risks in EMs and contagion to European periphery bonds. Combination of contagion from HY and political risks cd see re opening of European debt crisis.

Not much discussion of why oil went from $20 to $140 in the first place, um do you think it had anything to do with funny business in the denominator of those trades, e.g. the money itself? Lots of people crowing about how the oil market “works”, that it’s just reflecting demand, maybe they’ve also never heard of ICE? The offshore market where the big players can anonymously hit the bid on everything in sight, oh look, “the price is going up”. By some estimates they lost $500M in dumb trades whose sole purpose was to raise the price, then of course they just pocket the rise and much more in their core businesses.

In my view, *everything* is in a bubble caused by excess CB credit. Not just the prices of stocks and houses but everything from the number of nail salons in your neighborhood to the size of your big-screen TV. 30+ years of rampant credit creation has brought demand for everything from the future to the present…and that’s now past. No wonder corporate America isn’t investing because they don’t see the demand looking forward. Steve Keen’s Jubilee is the way out. Oh, that, or WW III. Looks like we’re getting the latter.

Perceptive comment, thanks. I had not thought much about why the oil price went so high so quick but now you mention it, and I look at the fraudulent price ratings of all sorts of other assets that have been recently revealed, yours is a persuasive suggestion.

If the marginal cost of production is that low, will the producers not produce more in order to pay off the debt? Resulting in an even greater glut and lower prices?

Yes. And pump they will as the economics will compel that. In effect they beating will continue till morale improves.

Remember that all-in marginal cost also reduces successor operator if the debt overburden reduced by a combination of loan work outs, asset sales, managed bankruptcies and loan write-downs.

That a lot of the spent capital is irrecoverable fully is a fact in a oversupply situation. It is only a question of who or in what combination the stakeholders bear the loss and in effect who gains. – the shareholder, lender and/or employee and certainly vendors including drillers and pipeline companies and indirectly the local municipality which may have cut deals to kick start the activity.

The likely hood in this case is all the above with the shrapnel flying far and wide as the loans and muni bonds have found their way to many portfolio’s via bond funds.

• as well, the falling oil price should still boost other parts of the global economy and markets and offset the damage done to oil producers, helping the oil price to stabilise via improved demand;

Given the lack of investment in the real economy and the crushing pressure on wages, I don’t see why so many commentators and economists take this as a given. To me, this looks a lot like the “supply creates demand” Say’s Law hocus pocus that should have been buried back when Say announced it. In our new economy, the goal isn’t to enable the workers to buy the good they produce; the goal is to soak the weaker to enricher the stronger. In that case, falling oil prices are just another sign of an impending deflation spiral.

Humm, supply creates demand… Let’s see… to create supply, you need capital (and social standing – they go together). Then you get others to demand your supply – hence they give you their money (or you extract it, same thing). So that may be why Say’s Law exists – it is the way the rich get richer! Ricardo was right!! – for him and his buddies… Just don’t ask Marx about Say’s Law and capitalists, haha.

AMEN! the LACK OF DEMAND across the Globe is being replaced by happy talk and central banks! Supply side economics , and trickle down theory , The Barbarians are at the gate while everyone is down at the collisium whatching Christians being devoured by the lions!

Are you sure about that? The last I heard was the Christians asking someone to throw them another lion.

Examples of enterprises that will benefit from falling oil prices:

Coal – there is several dollars of oil related production and transportation costs per ton of coal. Lower oil costs result in either lower coal costs or higher profits.

Trucking, airlines, delivery services (UPS, FedEx) all use enormous amount of fuels.

Manufacturing of many sorts, plastics, cement, foundries.

Farmers, both diesel fuel and fertilizer, which has large oil based components

All these changes in prices are complicated by the fact that many people hedge to lock in beneficial prices. I understand some shale producers have hedged up to two years output. Other producers and consumers of oil and gas routinely hedge.

The herd is spooked, do not underestimate the strength of fear.

Yes, there is nothing so powerful as fear. And as the post above makes clear – it’s contagious fear that sparks panic.

Panic, it used to be the word for what happened to markets. Now we can hardly use the word depression. I wonder how long “recession” has got. And what’s next – to try and stave off the specter of fear – what less scary word will they seize upon to lull the masses for a while longer? To convince us it’s really a buying opportunity?

Not so fast. I note that trading is handeled more by computers these days, and they don’t know fear. They just keep chugging along.

If investors paniced now, the damage would end up being smaller than if they panniced later.

Automated trading networks may be giving the banks a false sense of secuity. So they not only keep digging a deeper hole, but deside to dig faster and with more shovels.

Isuspect they will keep producing oil – until they literly run out of places to put it.

‘ … commodities-triggered 2008 style meltdown …’

Commodity prices are the messengers, not the bubble fuel. Loose monetary conditions (e.g., no-doc mortgages securitized and resecuritized in limitless volumes with AAA ratings to make silk purses from sows ears, in 2008) fuel bubbles, which of course drive up commodity prices. When the bubble pops, commodities drop back.

What’s was the bubble fuel this time round? Whisper it … ZIRP! And it’s still here!

So there was method to Larry Summer’s madness. We always need a bubble to keep money circulating. Who wants to face the bitter truth about deflation? Not me. The interesting tidbit above asked if insuring liquidity would buy us enough time to create a market based on “non-resource tradeables.” But it also made me think that at least for now a push to create a serious recycling industry is out because it would crash traditional commodities too fast to mitigate all the damage. We have created such a fragile world.

There is a difference with 2008 here, in that you’ve got the speculative shale play funded by junk debt which are sold via CLOs. The first time around, banks, which are the fragile part of the equation, didn’t have much direct exposure to the commodities roller coaster of 2008. This time they do.

And if they are writing CDS on the names in CLOs in an effort to hedge (or creating CDS for hedgies to bet against the shale complex and then trying to unload them as synthetic CLOs and getting stuck) as I am told they are, this could be a different picture. The involvement of CDS means you can create financial exposures way way in excess of real economy exposures. But these CLOs aren’t anywhere near as geared as the asset-backed securities CDOs, so in theory even with more risk here, the odds of a savage Sept. 2008 dislocation seem really remote. However, straight up plain vanilla oil and gas loans were enough to kill Continental Illinois and SeaFirst, two of the ten biggest banks in the US, back in the 1980s. And banks are much more interconnected now, so a couple of biggies or a bunch of medium sized one getting in trouble could have serious knock-on effects.

FYI, I have NC on WTF was just said here. Need better Q&A for better FAQ to feed the average

IQ and PDQ. LOL,

Let it crash already. The markets; the courts; the governments; the central banks; the corporate elite; and on and on are so thoroughly and completely corrupt that it’s only a matter of time. Why did the COMEX suddenly implement $100 price movement restrictions in gold and $3 price movement restrictions in silver? I don’t recall seeing any gigantic upward movements in the metals lately. “Investment” is a crap shoot and anyone saying otherwise is lying.

Trust has been broken and it’s not coming back until there is some accountability and enforcement of the law against TBTF.

‘the Fed can end this quickly if it wants to, up to that tipping point, if it stands behind market liquidity with more QE, which will reassure that oil won’t fall too far.

This ascribes almost magical powers to the Fed. Not only does QE raise stock prices, it also keeps crude oil well-bid, and eases bowel movements for ordinary citizens. Wunderbar!

Yes, that bit about the Fed being able to end this quickly if it wants to is nonsense. QE will do nothing.

I did sorta point that out in my intro. The Fed has all sorts of authority to lend, but getting liquidity where you want it to go is quite another matter.

Is it possible that any, all or a combination of hefty players like the Saudi’s or indeed the exchange stabilization fund could put on bearish bets such that the forward oil futures curve is bent downwards ? if you buy near months and sell later month futures in size you could give further impetus to the decline. Furthermore you would have long positions to dump on the spot markets as the near month longs mature.

Depending on how well you positioned your self before starting the ball rolling (remember your initial short sales would result in huge gains as the snow balling takes effect ).

Besides there is always the strategic reserves et al to be used to help the dynamic while eventually exiting the trade. With the Saudi’s they don’t even need to exit the trade – they just stop bashing the forwards and deliver to fulfill the short sales already made with oil they pump.

Also strategically a lot of assets could be picked up on the Cheap – say if Sinioec exists their stake in APLNG in your example at distress valuations.

So inn effect you put the kibosh on Russia, Iran el al and scoop up assets in Aus, Africa etc.

Sure you also wipe out some shale player equity and cause distress in hi-yield debt. Nothing some QE can’t fix. But mum is the word as the Powers that be cannot be seen dickering the markets or picking winners and losers in the shale melt down. But hey the melt down was going to happen any per the dynamic you described.

How is that for the outline of a novel – if only Paul Erdman were around.

What is to say this isn’t a feature of a recreation of the old Cold War, simply using new weapons and financial strategies to accomplish the same goals?

Yeah, I’ve wondered about that. ISIS, for example, is selling oil. This depresses their take. Along with the take of others. But it’s all so complex: so who is the real winner here?

Seems like we’re all gonna lose if this house of cards comes down. Scary!

But the question is, are we now living in a world with so many hazards (witness the tragedy in Pakistan today, the one in Australia yesterday, the damage to the Nazca hummingbird by Greenpeace the day before) … Too many hazards. So are we numb now? Too numb to know how to react: to which hazard should we to address our attention? How conceptualize the complex web we’ve woven, the net of our own making we’re caught in?

One gets the feeling precautions should be taken. If one could only fathom all the risks and options.

What is ISIS’ production cost?

What I don’t get is that percentage-wise, the supposed oversupply as well as drop in demand are not that big compared to the total amount of oil used/actually consumed. If, say 10% oversupply (93.3m bpd total demand as in the article, so about 9m bpd), is needed to drop the price like this, where is it coming from? Even Saudi-Arabia cannot swing production like this.

A 900.000 bpd demand drop is just about 1% compared to the actual use. That cannot cause such a violent price drop. In my opinion it was bubble pricing to begin with.

Have these energy company junk bond been hypothecated???

If they’ve been converted to CLOs or CDOs doesn’t that mean that they might be leveraged to the max?

In which case, the ride down might be quite steep and fast…..with liquidity vanishing on the way.

Am I wrong?

Yves?

Will commodities lead the next global financial crisis? I’m still watching copper. It’s shaky now, but when it joins the collapse then the ride really begins because of its use as collateral in the global carry trade. Investors will unload positions in commodities to raise cash for bond payments. Perhaps a quote from the Billy Ray Valentine school of economics is in order:

Okay, pork belly prices have been dropping all morning, which means that everybody is waiting for it to hit rock bottom, so they can buy low. Which means that the people who own the pork belly contracts are saying, “Hey, we’re losing all our damn money, and Christmas is around the corner, and I ain’t gonna have no money to buy my son the G.I. Joe with the kung-fu grip! And my wife ain’t gonna f… my wife ain’t gonna make love to me if I got no money!” So they’re panicking right now, they’re screaming “SELL! SELL!” to get out before the price keeps dropping. They’re panicking out there right now, I can feel it.

After the 2008 stuffing the US homeowner took, the elites learned (1) that they can pick who gets hurt by a crisis, and (2) that they can print their way out of any crisis that hurts them. I’m pretty much expecting that to be the model from now on. Which means that as far as commodities go, there’ll be no crisis in them unless the elites want there to be one.

Llewellyn-Smith nails it. I remember scratching my head at the runup in oil prices right after the last crisis seeing as how the entire world was in recession and actual oil consumption was declining rapidly. But the runup had nothing to do with actual physical consumption. It was all the excess liquidity which got channeled into commodities.

With oil futures being backed by physical delivery, you can only roll your forward contracts so long. At some point, thanks to the higher prices, the producers will eventually produce enough physical product to hold you to delivery. When that happens, the speculators stampede for the exits and the prices crash.

So the real question is: what asset class is next in line to be inundated with the barrage of QE ZIRP money?

Junkman 1: I can’t sleep at night anymore.

Junkman 2: Got so much gearing, but it isn’t moving. Nobody wants these 3-speed sticks anymore.

Junkman 1: Should of stuck with Dynaflow. I hypothecated all my carburetors to some guy that thought they were a French delicacy. Couldn’t bear to tell him about fuel injection.

Junkman 2: Well he can probably pour a tank of gas out of that pile you have when it is bug out time.

Counterpunch’s Mike Whitney, has an article titled “The Oil Coup” today, explaining how “US-Saudi Subterfuge Send Stocks and Credit Reeling”.

http://www.counterpunch.org/2014/12/16/the-oil-coup/

IIRC there was something about how oil prices are affected by speculation in Yves’ ECONNED. Haven’t got a copy handy to check this …

I would caution readers of this blog from joining the ‘doomer’ fraternity. About 2 years ago , the peak oil web site, I believe called the Oil Drum, closed its doors, basically because its thesis of world oil shortages had been discredited by events. Fracking has created a real revolution in energy. Accept low prices , and the possibility of renewed economic growth.

Oil shortages and the predictions in this piece of are two different things.

The key takeaway premise of this piece, and others like it, is one of unintended consequences: i.e. oil prices have dropped below the level necessary to allow energy producers to recoup their investment on fracking.

Low oil prices are obviously beneficial to consumers; however, the same low prices are putting energy producers and the financial institutions that underwrote loans to fund fracking operations in a precarious situation.

First, peek-oil is not some conspiracy theory. It’s based on the well established data that all oil wells will slowly peek in production, and gradually fall in production rates. When all known oil wells are added together, you end up with a similar peek shape which peeks out and gradually declines.

But there are a number of factors which will push the “peek” date further into the future; contracting demand through greater fuel efficiency or by economic pull back, in addition to new sources.

To my knowledge, the Oil Drum never discounted these factors in its projections. You can make an argument that there projections were overly pessimistic if you wish, and you may even have a case. But peek oil theory remains sound, despite the silencing of one web-sight.

I will note that I was always skeptical that the rise in priced to over 100dpB was caused by peek-oil predicted shortages. First, the peek oil crises requires demand for oil outpacing capacity for supply, this has not yet happened. A peek-oil crises also manifest in material shortages such as what was observed in the 70s, what we are observing now is simply market fluctuations.

I remain skeptical that the “oil revolution” is what it is advertised to be, and it certainly didn’t bust the curve. NC has reported on several occasions that shale oil and fracking projections were exaggerated, and that actual production has been falling short of projections for older plays. This forces drillers to deploy new plays in order to continue recouping more revenue to support the numbers from older plays, adding to the debt load and may contribute to over-supply.

I agree that peek oil is not at work here. But it remains an issue none the less.

It’s “peak oil,” ya dipstick.

Now write it 100 times – 10x for each “peek” you inflicted on your comment.

I don’t know how to make an image appear in this blog but the other day ZH showed basically how foolish oil company CFOs have been by buying back stock. For example, Exxon Mobile spent half of its 2013 profit buying back shares, thereby increasing shareholder value and weakening the company. It is my understanding (very weak) that retaining earnings or having large real estate holdings makes a company a target for hostile takeover or acquisition. Also, the execs making buy-back decisions likely get stock as part of their compensation package and may have bonuses tied to share price, so its obviously the right thing to do. And of course, the neo-liberal guru Milton Friedman stated that the goal of corporate governance is to maximize shareholder value. So, in a rational world, the majors would today be in a good position to acquire any smaller producer that became distressed. But in the world we actually live in, there’s not much in the kitty and the majors are cutting exploration, meaning that when price once again exceeds to marginal cost of production, including sunk costs, there would be shortages. To all you CFOs buying back stock like mad – Monty Python says: Brilliant!

I notice that efforts to push Keystone are still running full steam ahead.

it will be interesting as the scalding relief of these panics unload capitalism’s externalities