Yves here. Wolf provides a detailed and informative account of a new report by the Office of Financial Research on the risk of leveraged loans. The big finding is they don’t like what they are seeing. And on top of that, part of their nervousness results from the fact that the ultimate holders of leveraged loans are typically part of the shadow banking system, such as ETFs, and thus beyond the reach of bank regulators.

Because these loans were issued at remarkably low interest rates, they aren’t a source of stress. But as their credit quality decays (recall quite a few were made in the energy sector) and/or interest rates rise (the Fed is making noises again), investors in mutual funds and ETFs will show mark to market losses that could well be hefty. Any bank with large amounts of unsold inventory would also be exposed; query whether regulators will let them fudge by moving them to “hold to maturity” portfolios.

Oh, and what is the biggest source of leveraged loans? Private equity funds when they acquire or add more gearing to portfolio companies.

By Wolf Richter, a San Francisco based executive, entrepreneur, start up specialist, and author, with extensive international work experience. Originally published at Wolf Street

Office of Financial Research Slams Leveraged Loans

In its 2014 Annual Report to Congress, the US Treasury’s Office of Financial Research, which serves the Financial Stability Oversight Council, analyzed for our Representatives the “potential threats” to the US financial house of cards. Among the biggest concerns was a financial creature that has boomed in recent years. The Fed, FDIC, and OCC have warned banks about it since March 2013. But they’re just too juicy: “leveraged loans.”

Leveraged loans are issued by junk-rated corporations already burdened by a large load of debt. Banks can retain these loans on their balance sheets or sell them. They can repackage them into synthetic securities called Collateralized Loan Obligations (CLOs) before they sell them. They have “Financial Crisis” stamped all over them.

So the 160-page report laments:

The leveraged lending market provides a test case of the current approach to cyclical excesses. The response to these issues has been led by bank regulators, who regulate the largest institutions that originate leveraged loans, often for sale to asset managers through various instruments. Despite stronger supervisory guidance and other actions, excesses in this market show little evidence of easing.

How Did We Get Here?

Relentless QE along with interest-rate repression by the Fed and other central banks – “accommodative global monetary policy,” the report calls it – caused changes in “risk sentiment,” compressed volatility, and reduced risk premiums. To get a visible yield in an environment where central banks wiped out any visible yield, investors were “encouraged” to take on more and more risk, even for their most conservative holdings, thus moving “out of money market instruments and into riskier assets such as leveraged loans….”

During the “bout of volatility” in September and October, investors sold off these creatures, but it wasn’t nearly enough to dent the vast positions they’d accumulated. “On the contrary,” the report pointed out, “the fleeting nature of the episode ultimately had the effect of reinforcing demand for duration, credit, and liquidity risk, and led many investors to reestablish such positions.”

This Came at the Wrong Time

The credit cycle has four phases: repair (balance-sheet cleansing), recovery (restructuring), expansion (increasing leverage, weakening lending conditions, diminishing cash buffers), and finally the downturn (funding pressures, falling asset prices, increased defaults). Now the US is “somewhere between the expansion and downturn phases.”

Nonfinancial corporate balance-sheet leverage is still rising, underwriting standards continue to weaken, and an increasing share of corporate credit risk is being distributed through market-based financing vehicles that are exposed to redemption and refinancing risk.

Financial Engineering has Taken Over

Early on in the credit cycle, corporations borrowed money long-term to replace short-term debt and to fund capital expenditures. Now they use the borrowed money to “increase leverage such as through stock buybacks, dividend increases, mergers and acquisitions, and leveraged buyouts, rather than to support business growth.” And ultra-low interest rates and loosey-goosey lending standards have encouraged corporations to take “on more debt than they can service.”

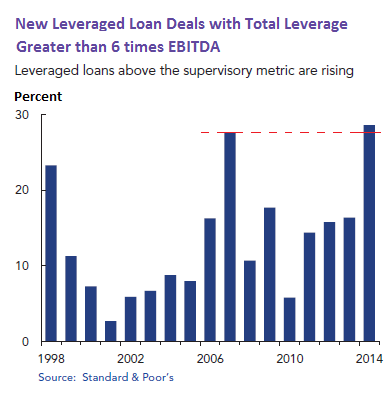

So the ratio of debt to earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation, and amortization (EBITDA) for the most highly leveraged loans reached 7.7 in October, near the peak in 2007, at the cusp of the Financial Crisis. Large corporate loans with leverage ratios above the regulatory red-line of 6 times EBITDA soared from 15% of corporate bank loans, back when regulators started warning banks about them, to nearly 30% in 2014, exceeding the record set in 2007 before it all went down the tubes:

Why would that be a problem? Because…. “Even an average rate of default could lead to outsized losses once interest rates normalize.”

And the Quality of the Debt Sucks

Junk debt accounts for 24% of all corporate debt issued since 2008, up from 14% in prior cycles. Over the past year, junk debt “dominated new issuance volumes.” And ominously for the holders of this debt: Two-thirds of these loans during the current credit cycle lack strict legal covenants to protect lenders, compared to one-third in previous cycles. Once the tsunami of defaults sets in during the downturn, these “covenant lite” loans will lead to lower recovery rates on defaulted debt, thus increasing the losses further.

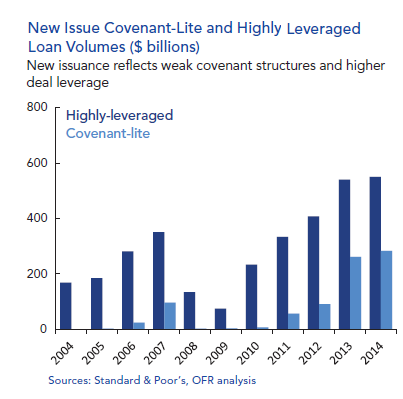

This chart (2014 data through September, annualized) shows how volume of “highly leveraged loans” (those with a spread of 225 basis points above LIBOR), at nearly $600 billion this year, is about 50% higher than it was at the cusp of the Financial Crisis. And the dreaded covenant-lite loans, oh my:

Now Enter CLOs

The combined issuance of CLOs and leveraged loans has exceeded the peak levels of the last credit cycle, whose downturn phase turned into the Financial Crisis. This buildup in credit risk has frazzled bank regulators, and they have responded harshly, the OFR reported, um, “with guidance and exhortations.”

It may be too little, too late. As the credit cycle enters the downturn phase with the deterioration in corporate credit fundamentals and rising debt levels, “the buildup of past excesses will eventually lead to future defaults and losses.”

But We’re Not There, Yet

Yields on leveraged loans and junk bonds, and spreads per unit of leverage, are still at historic lows, the OFR found (though some of it has very recently gone to heck, especially in the energy sector). And “investors are not being compensated for the incremental increase in corporate leverage.”

The increased credit, liquidity, and volatility risks – that “tend to rise simultaneously during periods of stress” – have led to these junk loans being wildly “mispriced.” When they’re repriced during the downturn, investors will lose their shirts.

And “product innovation” has soared, another “hallmark of late-stage credit cycles.” They led to “broader, cheaper access to credit such as exchange-traded, high-yield, and leveraged loan funds; total return swaps on leveraged loans; and synthetic collateralized debt obligations (CDOs).”

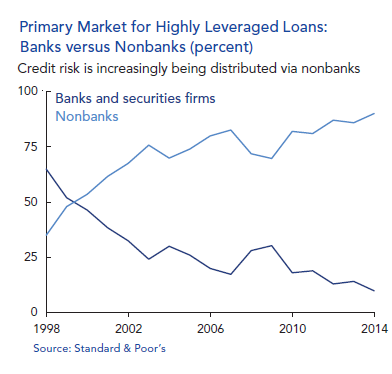

Banks, after originating these leveraged loans and repackaging them, increasingly sell them to nonbank lenders, such as institutional investors, pension funds, insurance companies, finance companies, mutual funds, ETF, etc. This process started long before the Financial Crisis – manifested by the collapse and occasional bailout of nonbanks, such as AIG. This chart (data through June 2014) shows this trend of risk being sloughed off to others:

The Problem with Nonbanks?

They’re not regulated by banking regulators. Even if the Fed, the FDIC, and the OCC crack down on banks with regards to leveraged loans, there is little they can do about nonbanks. And pushed to desperation by the Fed’s near-zero interest rates, nonbanks “engage in riskier deals than banks….”

Short-duration funds, which invest in leveraged loans, have shown the most significant growth. Assets under management have increased ten-fold over the last five years, driven by a search for yield and a hedge against an eventual rise in interest rates.

But banks can still be at risk when “a sudden stop in the leveraged lending market” – for example, when investors in ETFs and mutual funds get spooked – forces banks that originated these leveraged loans to hang on to them.

Yet a “significant amount of this risk continues to migrate to asset management products,” including mutual funds and ETFs that people have in their retirement funds. And investors in these products are largely on their own. When redemptions and fire sales start cascading thorough the system – the dreaded “structural vulnerabilities” – all heck could once again break loose. And that “adds urgency to the discussion” of how “a poorly underwritten leveraged loan that is pooled with other loans or is participated with other institutions may generate risks for the financial system.” Not to mention how it will savage the retirement portfolios of unsuspecting retail investors.

And some of this has already started happening in the energy sector. Revenues are plunging. Earnings will get hit. Liquidity is drying up. And stocks got eviscerated. Read… Oil and Gas Bloodbath Spreads to Junk Bonds, Leveraged Loans. Defaults Next

Hey, doesn’t this sound just like China?

“Catch-22 says they can do anything we can’t stop them from doing.” Heller

I think we can stick a fork in it. If 7 years of QE and zirp have only managed to maintain life support and world war is out because it is even more destructive than our melt-down economix fiasco… then what else can we do? Derivatives might even come to the rescue. Don’t those CLOs have derivatives contracts included in them? Everything is a commodity, right? So derivatives go hand-in-glove with credit armageddon. In the end only insurance policies can defend against the four amigos. And ETFs can instantly decline the losses out to the 50th person in the greater fool pool so that everybody takes a little nick and the debt is painlessly disappeared. When it defaults. Last nite on France 24 two socialists, one conservative and one irritated German debated whether France and the EU were really deflating. The German guy said not at all – everybody was just trying to get out of their debt obligations; the socialists said yes and austerity was the culprit and the conservative was great: he said “the (economic) model has reached its limit.” And he asked why anyone should participate in an economy that is clearly not functioning and will leave investors holding the bag. Once again. It’s the system. (Well “system” is truly a euphemism, but anyway, somebody finally said it.)

It’s like déjà vu all over again. CMO’s, CLO’s, synthetic CDO’s, CDS, insurance companies, and banks left holding the bag of shit they were going to sell off to the muppets.

Nothing that can’t be fixed with a taxpayer bailout, fiscal austerity, wage regression, financial suppression (negative interest rate on your savings account), Fed overreach, and ignorant/arrogant words of wisdom from the elite oligarchs who will ultimately profit from the coming financial crisis. Oh, and more war.

Looking at how these loans are structured and what the loans are being used for, it points to a problem with liabilIties.

Companies take out capital loans at junk rates to fund stock repurchases.

What if the loans are repackaged and sold to a investor group.

Said group calls all loans in that bundle due to a part of the loan package defaulting.

All of a sudden said companies have liquidity crises and can’t pay the loan.

Seems like this trend has everybody gathering in an slaughter house for a party, not knowing they are really the cattle.

I think the real difference this time is that the really big banks have lots of liquidity on hand. I have read that there is over a trillion$ on their balance sheets and have been discussing charging large depositors rather than paying them any interest on their balances. So in some weird ways, the FED has been preparing them for just this kind of bond collapse.

With all the leveraged deals out there and margin on stocks, I just have no idea how this plays out this time around. Certainly it will be different than last time.

As for derivatives.. from what I know, that is kind of a stupid game because mostly the TBTF are just insuring each other.. So in a bad decline, they just cause more trouble and losses. Besides, many are so complex that the outcome would be a decision of some court and not just an automatic anything.

So far, this is just more drama on the Hudson and Potomac and nothing else. I’m sure the end game was for the really big financial players to own it all, including big oil which I think has been their rivals for decades now.. Just the big Monopoly game and we as citizens and consumers are just that same as serfs and slaves in the eyes of the big players.

Did you not read the post? The final chart clearly shows the final investors are NOT banks for the most part. And a some of the bank holdings will be temporary, since banks make the loans and then sell them on. To the extent banks are the final holders, moreover, I’d hazard a fair chunk are Japanese (the Japanese were regular buyers in the old LBO loan syndications).

Sorry Yves, I did read it twice.. Somewhere I have read about the huge mountain of derivatives that someone is holding and was thinking that so much that the TBTF have to be a major holder of them. Who else would be? And Maybe there is enough liquidity in the system that this would play out completely different than the last time when sub-prime housing and auto defaults almost collapsed the TBTF. Maybe this time it is everyone else who is at risk and will take the big fall? And all that liquidity that the TBTF are holding will be a great buying opportunity for them.

The final investors are often (not exclusively) investment companies like Blackstone, Carlyle, Ares, Apollo, Guggenheim, etc. And the equity in their vehicles is largely institutional investors, hedgies, and wealthy individuals (family offices). They have been clipping HUGE returns for the last 4 years or so (I mean like 20 – 40% yearly) on the equity as a result of the Fed’s asset reflation strategy. Cash-flow vehicles made a mint in this cycle; mark-to-market vehicles got crushed. So natch, Wall Street is pushing, and piling into, cash-flow vehicles again, on the premise that the next war will be a replay of the last war.

“Oh, and what is the biggest source of leveraged loans? Private equity funds when they acquire or add more gearing to portfolio companies.”

Private equity: the gift that keeps on giving.

Leverage. No economist here. But the post on “superiority” of economists seems to pertain to this one.

Leverage. Wasn’t it Archimedes who stated that with a long enough lever one could lift the world? That’s one metaphor: leverage as objective, mathematically and scientifically.

The other metaphor is Icarus: leverage as myth – works for a while, until it doesn’t.

You can count on a true lever. You can verify it, predict it, test it. But bundles of non-sense, sold as “something” are like the wings Icarus believed would allow him to fly close to the sun. The wax, holding the wings together melted… So much for mythical leverage.

This is what the report says. Copied and pasted from the governmint’s publication. Not exactly a “sky is falling” fire-alarm!

but they sure may be wrong. Everybody has been wrong at least once over the past 7 years.

If you watch it long enough, you see that economic forecasting is like a broken clock — the face spins around and around but the hands don’t move. When the face spins underneath the hands they say “See. We saw it coming!”

Analyzing Threats to Financial Stability

Chapter 2 details where risks have increased over the

past year. The focal point of this analysis is our Financial

Stability Monitor, introduced last year, but refined, broadened,

and deepened for this report. The monitor displays

the buildup of vulnerabilities across five broad categories

of risk — macroeconomic, market, credit, funding and

liquidity, and contagion — based on a set of models, surveys,

financial data, and other indicators.

The monitor shows that although overall risks to financial

stability are not particularly elevated compared to the

pre-crisis period, some have clearly intensified over the past

year. One particular concern is market risk, which is the

vulnerability of investor portfolios to large losses because of

unanticipated adverse movements in interest rates, exchange

rates, and other asset prices. The monitor also shows elevated

risks among nonfinancial corporations in the United

States because of relaxed lending standards, lower credit

quality, higher debt levels in relation to total assets, and

thinner cushions to counteract shocks. Market liquidity risks

have also increased, in part reflecting structural changes in

the way liquidity is provided

I was beginning to wonder if Larry Summers was right, and it was to be bubbles all the way down. Maybe he is right, and this is just a catalyst to pop the most recent bubble and begin afresh. But maybe… just maybe… the Saudis have done us all a huge favor. Oil is the real deal, not a human construct. Anyone else wondering why oil remained over $80 bbl for the four years ended June 30th?

http://www.spunk.org/texts/prose/sp000212.txt

ridiculous how these people named Wolf are so precipitate regarding investment vulnerability

Can someone explain in plain English what a leveraged loan is? How does it differ from an ordinary loan?

From the article:

… “Leveraged loans are issued by junk-rated corporations already burdened by a large load of debt.”

… “So the ratio of debt to earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation, and amortization (EBITDA) for the most highly leveraged loans reached 7.7 in October, near the peak in 2007, at the cusp of the Financial Crisis. Large corporate loans with leverage ratios above the regulatory red-line of 6 times EBITDA soared from 15% of corporate bank loans, back when regulators started warning banks about them, to nearly 30% in 2014, exceeding the record set in 2007.”

So why is financing (banking in particular) not regulated as a component of public utility again? I’m making a list of citizen demands and this is on it. Add as you wish.

Richter wrote:

To get a visible yield in an environment where central banks wiped out any visible yield, investors were “encouraged” to take on more and more risk, even for their most conservative holdings, thus moving “out of money market instruments and into riskier assets such as leveraged loans….”

In my opinion this is too simplistic of a view. From a wider point of view it could be argued that with increasing inequality there are too many savings concentrated in few hands in search of any kind of investment. Since consumption growth is muted there are not many productive investments at hand and those savings tend to end funding improductive investments or asset bubbles. In my opinion Wolf Richter tends to put all the blame in central banks ignoring the general picture. Despite this, I always read Richter’s juicy posts with pleasure.

I agree with ANCAEUS: Can someone explain in plain English what a leveraged loan is? How does it differ from an ordinary loan? And just as important, how should an ordinary investor due their due diligence in recognizing these types of loans in any mutual funds they may own?

It wouldn’t be inaccurate to think of leveraged loans as the mid-to-large business equivalent of subprime. A bank extends a loan to a firm with less than stellar credit rating (usually because the firm is already heavily indebted) and said bank now owns the subprime firm’s debt. The bank takes that debt and packages it up as a security, selling it to some institutional investor. Because leveraged loans carry more risk, they pay a greater interest rate, which is why investors want them. The loans are typically secured with the assets of the borrowing company so owners of the debt are likely to get more in settlrment should the borrower default.

Leveraged debt is “non-investment” grade, making it a step up from junk bonds. It’s typically rated in the BB+ to B- range, assuming you trust S&P.

Thank you!