The F-35 fighter jet is the most expensive weapons program in U.S. history, but one of its biggest failures isn’t in the air — it’s on the ground. The Pentagon’s Autonomic Logistics Information System (ALIS), conceived as an ambitious plan to revolutionize fighter jet maintenance and logistics, collapsed under the weight of bad design, poor coordination, and perverse incentives that reward failure as readily as success. Its troubled successor, the Operational Data Integrated Network (ODIN), has stumbled out of the gate, revealing a deeper, recurring syndrome in U.S. government technology programs — a systemic incapacity to deliver on large-scale, high-cost projects, where failure is not just common but structurally baked into the process. This article uses the rise and fall of ALIS, and ODIN’s faltering replacement effort, to illustrate how that syndrome operates and why it persists.

ALIS in blunderland

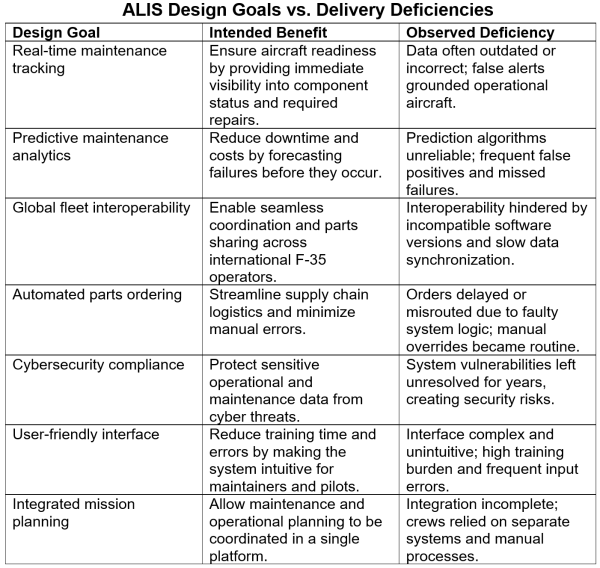

ALIS’s collapse was not the result of a single flaw but of compounding failures that undermined it from conception to deployment. Conceived as the digital nervous system of the F-35 program, ALIS was meant to track parts and maintenance in real time, streamline repairs, predict failures before they happened, and connect a global fleet with seamless efficiency. In reality, it became a sprawling, brittle, and chronically unreliable burden. Software updates routinely broke existing functions, maintenance crews spent as much time troubleshooting the system as servicing the aircraft, and pilots were grounded not by enemy action but by bad data and system errors. What was billed as a force multiplier instead became an expensive liability — a case study in how poor architecture, weak oversight, and skewed incentives can cripple even the most critical capabilities.

Israel Says No to ALIS

Perhaps the most telling indictment of ALIS came not from a congressional hearing or a Pentagon audit, but from the operational choices of one of America’s closest military partners. In 2016, when Israel received its first F-35I “Adir” fighters, it declined to connect them to the global ALIS network at all. Instead, the Israeli Air Force built its own independent logistics, maintenance, and mission systems to support the jets. Officially, this decision was framed as a matter of sovereignty and cybersecurity — Israel wanted to ensure that no foreign entity could monitor or interfere with its aircraft operations. Unofficially, it was also an acknowledgment that ALIS, as delivered, could not be relied upon for timely, accurate, or secure sustainment.

For a program whose central selling point was a globally integrated logistics backbone, one of its earliest foreign customers effectively voted “no confidence” and walked away, creating a precedent that other partners quietly noted. The Pentagon’s answer to such mounting dissatisfaction was ODIN — a fresh start in name, but as events would quickly show, a system fated to inherit many of the same flaws that doomed ALIS.

Israeli F35I Adir – Don’t ask ALIS

ODIN: The Replacement That Stumbled

In 2020, the Pentagon announced that ALIS would be phased out and replaced by the Operational Data Integrated Network (ODIN), a “modern, cloud-native” system promising faster updates, stronger cybersecurity, and a leaner, modular design. But almost immediately, ODIN began exhibiting the same flaws it was meant to fix. Hardware shortages delayed initial deployment, integration with legacy F-35 data pipelines proved more complex than anticipated, and shifting requirements coupled with uncertain funding caused repeated schedule slips. Most tellingly, ODIN’s reliance on a patchwork of government, Lockheed Martin, and subcontractor teams recreated the fractured accountability that had hobbled ALIS from the start.

By 2023, the Department of Defense quietly acknowledged that ODIN would not fully replace ALIS for years, and in some cases, the two systems would operate in parallel indefinitely. This hybrid setup perpetuated the very inefficiencies ODIN was supposed to eliminate — maintainers still had to wrestle with multiple interfaces, inconsistent data, and duplicated workflows. In effect, ODIN became less a clean replacement than an ongoing patchwork, weighed down by inherited design flaws, bureaucratic inertia, and the same perverse incentives that rewarded visible activity over actual capability.

The Consequences of Failure

Despite roughly $1 billion spent on ALIS and hundreds of millions more on ODIN, the F-35 fleet’s mission-capable rate remains stuck at about 55%, far below the 85–90% target. ALIS’s failures—and ODIN’s slow rollout—have contributed to chronic maintenance delays, inflated sustainment costs, and reduced operational availability, undermining the F-35’s ability to meet its core mission requirements.

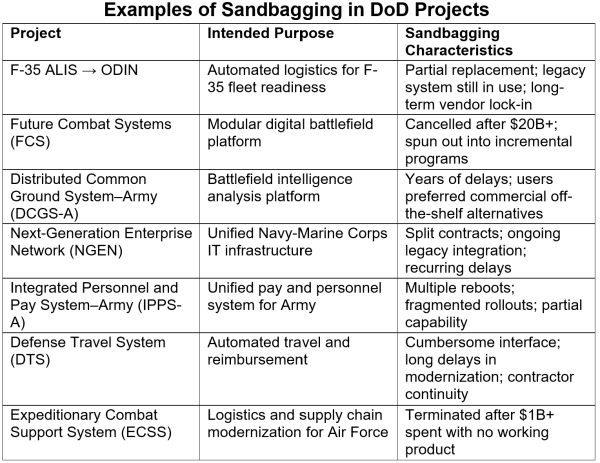

From ALIS to the Bigger Problem: Government Project Sandbagging

The ALIS debacle — and ODIN’s halting attempt at redemption — is not an isolated failure but part of a recurring pathology in large U.S. government technology programs. This broader failure syndrome, which can be called project sandbagging, thrives in environments where perverse incentives reward slow progress, extended timelines, and budget inflation over timely, effective delivery. In such programs, failure rarely harms the contractors or agencies involved; instead, it becomes a pretext for additional funding, prolonged contracts, and diluted accountability. The very complexity that justifies massive budgets also shields programs from scrutiny, allowing delays and underperformance to be reframed as the inevitable costs of “managing risk” in ambitious projects. Too often, progress is measured in notional milestones and funding appropriations rather than delivered capability. ALIS is simply a particularly vivid example of how sandbagging erodes readiness, wastes resources, and normalizes failure — a fate shared by other major Defense Department technology projects.

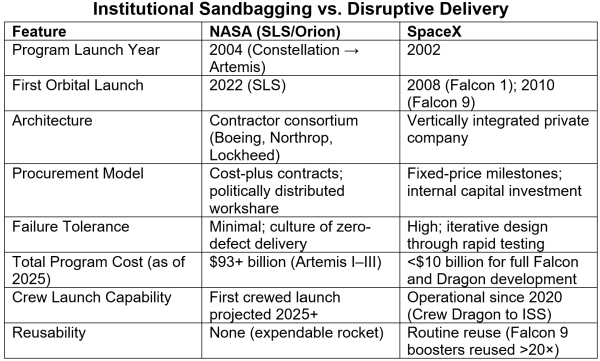

When the Sandbags Are Removed: SpaceX vs. NASA

The gap between SpaceX and NASA’s congressionally directed SLS/Orion/EGS program is a rare natural experiment in incentives. Under fixed-price, milestone-based Space Act Agreements, SpaceX fielded Falcon 9/Heavy and Crew Dragon and built multiple Starship prototypes on rapid cycles; NASA, by contrast, has spent over $55 billion on SLS, Orion, and ground systems through the planned Artemis II date, with per-launch production/operations estimated at about $4.1 billion—a cadence and cost structure widely flagged as unsustainable.

SpaceX’s COTS/CRS/Commercial Crew work tied payments to verified, operational outcomes (e.g., ISS cargo and crew delivery), with NASA’s own OIG estimating ~$55 M per Dragon seat versus ~$90 M for Starliner. In contrast, Congress required NASA to build SLS with Shuttle/Constellation heritage and legacy contracts — locking in cost-plus dynamics, fragmented accountability, and low competitive pressure. While SLS is designed for deep-space crewed missions and thus faces higher safety margins, its cost and schedule gulf with SpaceX still reflects a stark disparity in structural incentives: one path rewards delivery and efficiency, the other sustains delay and budget growth under the banner of “managing risk.” That disparity is the essence of project sandbagging — a system where progress is measured in notional milestones and funding appropriations, not delivered capability.

Conclusion

The failure of ALIS is not a rare mishap — it is a case study in a chronic U.S. government failure mode. It reflects a recurring pattern: fragmented accountability, contractor dominance, risk-averse governance, and illusory milestone-driven progress that substitutes process for performance. Like many federal IT programs, it was built under cost-plus contracts, insulated from disruptive innovation, and allowed to persist despite user distrust and operational dysfunction.

The slow, incomplete transition to ODIN has not resolved these flaws — it has entrenched them. ALIS’s legacy is more than the logistical hobbling of the F-35 program; it is a warning that without structural reform in procurement, oversight, and incentives, critical technology projects will continue to sandbag transformation while consuming vast public resources. If future programs — including those now on the drawing board — are to avoid the same fate, the cost of inaction must be understood as measured not just in dollars, but in lost capability.

Curbing the entrenched practice of project sandbagging will require reforms that change both the incentives and the accountability structures that sustain it. The following measures address the pattern of incentive and oversight failures that doomed ALIS and now hinder ODIN:

-

Tie contractor profit to operational outcomes, not just deliverables.

Move away from cost-plus contracts toward milestone payments linked to verified, in-service performance. This makes profit contingent on the system actually working as promised. -

Enforce independent technical audits at multiple project stages.

Mandate third-party verification of progress, functionality, and readiness before approving further funding. Auditors should report directly to Congress or another oversight body, bypassing the program office’s chain of command. -

Adopt modular, open-architecture requirements.

Design programs so that components can be upgraded or replaced independently. This reduces lock-in to flawed subsystems and encourages competitive sourcing. -

Institute “sunset clauses” for underperforming programs.

Set predefined thresholds for cost, schedule, and readiness; if breached, the program must be re-competed, restructured, or terminated. This makes failure a risk for the implementers, not just the warfighters.

By shifting incentives toward timely, functional delivery, these measures would make it harder for stakeholders to profit from delay and under-performance. The F-35’s ALIS and ODIN experience demonstrates what results when such guardrails are absent: costly, drawn-out efforts that erode readiness while delivering far less than promised. That is the central lesson of ALIS and ODIN, and why systemic reform is mission-critical. Until the sandbags are removed, the United States will keep mistaking motion for progress — and paying a premium for failure.

ALIS is garbage in garbage out.

F-35 ran out of time and money to gather failure modes and effects data. That meant any data about what a part failure (the navy description is “casualty”) is incomplete if not in error. In part they could not fly/operate the object hardware/software enough, that cost money and hampered by poor reliability.

That error made mil spec tech data a problem.

Incomplete reliability science and diminished repair plans.

The rest are bandaids on an arterial wound.

There are probably Lockheed and sub vendor engineers.

The F-35 does not have a central maintenance computer like airliners designed after the 1980s? That’s backwards.

A second reply.

Airlines have had many of the ALIS functions for at least forty years. Airliners have been downlinking warnings, fault messages and system reports for the same time period. Newer airplanes (777, 787, A380, A350, A220) send a ton of information every flight leg that is used by maintenance, aircraft manufacturer and powerplant manufacturers. Full flight data with a high sampling rate for system analysis and predictive models is also available if the airline installs the collection/transmit equipment and subscribes to the monitoring program.

The parts and planning was available when airlines were using terminals to access mainframes.

An airline may have 15% or so of its aircraft in short or long term maintenance. I was surprised when sharing aircraft monitoring practices with the US military at how high their fleet out of service rate was. (Granted, military airplanes have more systems to maintain, such as weapons and electronic warfare. Also, the maintainers may not have as much experience as airline personnel.)

(I also don’t agree with an up-or-out policy. Some positions need people with 10 ~ 15 years of experience to be proficient and knowledgeable.)

Curiously the word “corruption” – the heart of these multi-system “features” – is not used once in this otherwise very good article.

The word itself, no. But the entire article is a case study in how the corruption is built in as SOP. He did point out the example of Congress forcing NASA to use warmed over shuttle systems and their pre-existing contractor baggage, the only part missing was the bucketfuls of cash ‘ contributed’ to Congress by Thiokol and the rest, for ‘protecting the jawbs’. But then this is Congress we’re talking about, so that kinda goes without saying.

Yes…it kinda does go without saying. But my corruption fogged googles compels me to say it even when it doesn’t need to be said….argh!

Sounds like Doge should leave the National Parks alone and go after the Pentagon. Of course as we know the real goal is to cut environmental and social spending so the Pentagon can have even more money. Your Masters of the Universe have their own priorities.

One should mention that the F 35 itself had an endless gestation period. Lockheed had and I assume still has a faciltiy in Cobb County Georgia and I recall seeing F 35 prototypes flying out of Dobbins AFB in the late 90s. Why have the Israelis bought the plane at all other than to appease their far away backers? Allegedly they wisely kept them out of Iran during the recent conflict and when it comes to bombing tents any old jet will do. Should the Iranians in fact get the latest Russian air defense then the next attack from Israel may produce some interesting results.

I could show DOGE where to start in about three hours!

Someone has kept DOGE from going into the pentagon.

Few systems in the DoD can be valued against the specifications that were presented for payment, thsat scarcely match the part delivered.

AI won’t work in the pentagon bc hardly anything in file is accurate.

DOGE is run by Musk and the Hobbit-botherers who are some of the biggest defence contractors.

Some show pieces and MIC jobs program stuff.

The USA has been weaving its way thru the world with hype and keeping other people fighting each other.

One other example: The USA gets more mileage out of the hype of AI over whatever weapons developments may come to being.

One thing about SpaceX is that i have a strong feeling it is running at a lose with each rocket launch. They don’t give an exact breakdown of where the small profit in SpaceX comes from. But it looks to me like that largely comes from starlink. SpaceX can hide costs in a way that NASA can’t.

Musk does government launches, takes astronauts to the space station, gives rich people joy rides, is supposed to be part of the return to the Moon if that ever happens.

So Space X is not just about Starlink and commercial launches.

Carolinian: SpaceXis supposed to be part of the return to the Moon if that ever happens.

In the real word, Musk’s launchers can only reach LEO.

So on the evidence Musk is in this respect as in almost every other — I’ve gone on here on NC previously at tedious length about the ludicrous unscientific stupidity of his Mars Starship claims — ludicrously full of bovine excrement.

Starlink is over 60% of SpaceX income. My query is, does SpaceX chsrging it’s launched at the actual cost plus a bit of profit? Or is it being priced at a loss to corner the market? Before claing they are doing those so efficiently that has to be known.

I’m sure some office at the Pentagon has big spreadsheets comparing the Russian and Chinese Gen 5 programs to the F35 and F22. Probably edifying.

Old Maverick shot down an SU 57 in an old F-14…..

..after stealing it under the nose of a couple of idiots who strongly reminded me of the 1980s nimwit Ruskies but now had to be without any nationality (because of those who co-financed the movie and didn´t want American movie-goers think it´s Iran?).

Oh and what struck me was how prominently the fact was present that NATO was involved, I think…

Even the original Topgun didn’t have protagonists from a specified country. They were miscellaneous baddies.

aha ok!

Apparently I had conveniently forgotten about that…

Well, I never liked TG anyhow…

American movie-goers can check Wikipedia list of all operators of F-14. It’s a rather short list.

Haig> This broader failure syndrome, which can be called project sandbagging, thrives in environments where perverse incentives reward slow progress, extended timelines, and budget inflation over timely, effective delivery.

Fixing defence spending especially the cost-plus model was the Anduril’s original 2018 pitch:

[Palmer Luckey:] Innovation isn’t just about doing the right thing or doing the smart thing. A lot of it is actually about the business incentives and the structures. I think right now a lot of defense programs are done on cost-plus contracts that incentivize very long schedules, building custom parts whatever you can justify rather than what you need to. Doing excessive testing whenever you can justify it, rather than when you need to.

If you compare the results of those types of programs with the results of the consumer technology industry, the results are striking.

Cost-plus reform was a major plank of Palantir’s 2024 manifesto (“The Defence Reformation”):

Cost-plus contracting makes the nation dumber, slower, and poorer.

Maybe it is the right way to buy an aircraft carrier, but it is the wrong way for 95% of things. It robs any reward for going faster or developing innovative approaches, institutionalizing a lack of incentive to compete on price by valuing time spent over time saved. SpaceX reduced launch costs by 85% — that simply isn’t possible in a cost-type domain. In fact, NASA estimated the cost of developing the SpaceX rocket at $4 billion when SpaceX did it for $400 million. Cost-plus is the reason that defense costs grow faster than inflation and don’t result in compounding price performance decreases. In the commercial world, people are viewed as expensive, and technology is considered cheap. In government, there is a perversion where people are viewed as abundant, and technology is viewed as unaffordable. Meanwhile, Starship will reduce launch costs 100x over Falcon 9 and 1,000x over the progeny of cost-plus approaches in a timeline that is well inside the development loop of the $2 trillion, 30% available F-35.

—-

Haig> Adopt modular, open-architecture requirements.

Design programs so that components can be upgraded or replaced independently. This reduces lock-in to flawed subsystems and encourages competitive sourcing.

“Modular” is another major plank of the Anduril pitch both the flexible Tesla-style Arsenal-1 facility in Ohio

Arsenal-1 will enable Anduril to produce autonomous systems that are specifically designed for simplicity, modularity and mass-producibility.

and the systems themselves

The three versions of the subsonic Barracuda cruise missile — dubbed the Barracuda-100, -250 and -500 — are built using common subsystems that can be easily swapped in and out as new technologies are developed or threats emerge, Anduril said, which makes them highly adaptable. They will be able to conduct direct, stand-off or stand-in strikes, the company said.

Barracuda’s modularity will also make it attractive to international customers, said Chris Brose, Anduril’s chief strategy officer.

“You can take it apart like Lego blocks,” Brose told reporters in a Wednesday call. “It makes it a lot easier to work through and navigate defense export issues and collaboration with allies.”

There is a large bit of skullduggery in DoD procurement and cost management!

When the pentagon/government uses “cost plus” it reviews the contractors cost, schedule, performance using “earning value” accounting. That has been around since way before they put PERT on computers in 1970’s. Microsoft project does a reasonable job on PC.

Somewhere about 30 years ago the DoD threw away its mil standards for cost schedule control system (CS square). Now contractors use commercial PERT’s, and commercial project management SW..

The contractor reports cost and schedule variances each quarter. From those reports DoD PM can see estimate at complete (EAC). Usually it shows potential failures and delays early! But every PMr is filled with hopium all the way to running out of time and budget.

The main feature of “cost plus” is the government manager has to act to “terminate” when EAC is fiction. There are no incentives for this! In fact the DoD PM is likely to get canned!

“Fixed price” the contractor does not have to report PERT at all, but has schedule reports and has the responsibility to tell the DoD PM “we cannot get there from here”.

Again the contractor PM gets canned….

DOGE could look here! Particularly at how true to performance and functional specifications is the “earned value’ claimed, each report!

We’ve used CPIF and CPAF contracts in a lot of procurements. It isn’t some sort of magic bullet, but we did get improvements in CG/DDG delivery costs and schedule. But they transitioned to FPIF as they went into serial production.

I’m a ships guy, but the air side developed NALCOMIS over the years to manage O and I level maintenance. Evolved over time to NTCCS which added other support functions. In the early years USG laws/policy on ADP created a firewall between “tactical” systems and “non-tactical”, with GSA inserted as gate to ADP projects. I think that has mostly been streamlined now but the legacy lives on. But the thing with ODIN is the push to put everything into the cloud. I know the general attitude here is that it’s all corruption, but a big part I believe is the idea that industry has moved everything into the cloud so we need to too.

As far as the “sandbags”, I don’t know; looks like a silver bullet to me.

As far as “that’s not how comm air does it”, great. When comm air starts flying from ships at sea while being shot at, then come talk to me.

It seems the indigenous, American elephant in the room, is why contractors are necessary at all?

Probably find that it all comes down to lack of competition and for this one you can blame Bill Clinton. I think that it was in the late 90s that reps from the government told all the big defense companies that they had to amalgamate into bigger conglomerates – or else. The small handful of MIC corporations today are a result of this which means that there is no real competition to cut costs or even deliver something halfway workable.

Rev K: you can blame Bill Clinton. I think that it was in the late 90s that reps from the government told all the big defense companies that they had to amalgamate into bigger conglomerates – or else.

Indeed. You refer to William Perry and the infamous Last Supper of 1993.

Les Aspin was still Defense Sec, but Perry, then Deputy Secretary, delivered the message at a dinner for defense CEOs that post–Cold War budget cuts meant the Pentagon could no longer sustain so many contractors, triggering a massive wave of mergers and acquisitions so the number of prime contractors shrank from 51 to just 5 over the following years.

It had the opposite to its professed intent.

Rev, the below is from the same Palantir Manifesto I linked above:

In 1993, after the Cold War, U.S. defense spending was cut by 67%. At the Pentagon’s “Last Supper,” the Secretary of Defense told 51 prime contractors they would not all survive. Today, only five remain.

Before the Berlin Wall fell, 6% of defense spending went to defense-only firms; most went to companies with both defense and commercial lines. Chrysler made cars and missiles, Ford made satellites until 1990, and General Mills made artillery and guidance systems.

The Last Supper’s real impact was not just reduced competition but the separation of commercial innovation from defense and the rise of a government monopsony. Consolidation drove out founders and innovators, creating the “Great Schism” of the American industrial base.

Today, 86% of defense spending goes to specialists. Working with the monopsony is so unappealing that companies like Ball prefer making beer cans over satellites. The S&P 500 hadn’t added a defense company in 46 years until Palantir joined in September 2024.

Cost-plus contracting, heavy control, and regulation have made national defense unattractive to dynamic businesses, leaving it to risk-averse investors focused on dividends and buybacks — a model for declining, not growing, sectors.

Michaelmas & Ben Panga

Thanks guys for that info. Unless the US nationalizes those six corporations or breaks them apart, then I guess that nothing will change. On the other hand there may not be a war with China as the Pentagon will let it be known that they can’t do it. Better to make a peace instead.

Or, instead of peace,….how about pouring trillions into AI and killer-drones that will eventually slaughter us all?

Sure. On the Aegis Combat System program we went from RCA to GE to Martin Marietta to Lockheed Martin. Pretty much all the same people, just the logo kept changing.

The following is a rumor I heard about 30 plus odd years ago.

Bush Sr. looking at the world and the impending end of the cold war said: “why don’t we just build a few prototypes of new weapons and test around them bc we have no worries from the Soviets”.

That got shot down bc the real money in a weapon system is in “padded” fixed price production and now that he DoD does not buy repair data in sustainment contracts at heavy cost plus.

I wonder if he scared the MIC and they chose Clinton?

Have no idea of that. We develop our Integrated Logistics Support Plan (ILSP) and Navy Training Plan (NTP) and out of that falls the requirement for data. A big factor is the requirement A-sub-O and consequent MTBF and MTTR. We determine the LRUs and repair of repairables/maintenance plan.

Of course in COTS procurement there will be battles over technical rights in data DFARS clauses to use.

One of my programs where I was system engineering manager, because of a removal of nuclear weapon capability we were transitioning the hardware from dedicated (Rohm Milspec which was a ruggedized Data General mini-computer for which we owned or licensed all data down to the component level) to HP workstations where our code ran on HPUX OS. So obviously HP is only going to let you have just so much data; the defense business was a small slice of the total market for these things. You have to run your trades to see how to make that work.

BITD the idea was to buy everything with “standard electronic modules” (SEM) and train / support shipboard repair via “micro-miniture” (2M) repair stations. But by the time you do that, it might be easier just to go COTS and buy a few extra workstations and swap the whole thing out. The real cost of the workstation wasn’t the actual HP hardware; it was all the stuff needed to meet shock/vibe, environmental, and EMI/ECM/TEMPEST requirements that more or less encapsulated the HP stuff (those bits designed and built by our friendly LM contractors).

re: last supper

1) WBUR podcast

‘The last supper’: How a 1993 Pentagon dinner reshaped the defense industry

March 01, 2023

Guests

Norman Augustine, former chairman and CEO of Lockheed Martin. U.S. undersecretary of the Army from 1975 to 1977.

Rep. John Garamendi, Democratic Representative for California’s 8th congressional district. Member of the House Committee on Armed Services and the House Committee on Transportation and Infrastructure.

also featuring:

Taylor Giorno, money-in-politics reporter at OpenSecrets, a research and government transparency group tracking money in politics and its effect on elections and policy.

by Jonathan Chang, Meghna Chakrabarti

47 min. / transcript

https://www.wbur.org/onpoint/2023/03/01/the-last-supper-how-a-1993-pentagon-dinner-reshaped-the-defense-industry

2) Washington Post

HOW A DINNER LED TO A FEEDING FRENZY

By John Mintz

July 4, 1997

https://archive.is/Ogstz

Maybe there’s some unnamed heroes in those programs sabotaging from the inside. Keeps the self licking ice cream cone gravy train rollin. Win win.

i chuckled he first time i saw the famous cartoon in which medical students are taught that ” a patient cured is a customer lost”. it seems this principle can be generalized well beyond medical care. in other words, the problems with the f-35 and many other defense programs are really not problems at all; they are opportunities. seen as such, any plans for fixing the failures are in vain. already, the incapacity of the fifth generation f-35 has lead to planning for the next, sixth generation fighter. no doubt even more complicated, more fragile and more prone to failure than the f-35.

A lot of the ALIS/ODIN core difficulty seems to relate more to IT / general software practices, which tends to negatively shine in large gov projects

https://xkcd.com/2030/

(without dissing MIC corruption’s natural layering).