HSBC’s CEO Stuart Gulliver and Chairman Douglas Flint put in an appearance in front of the Treasury Select Committee on Wednesday 25th February. As usual with these banker-bashing shindigs, the session was tense, with plenty of pointed questions and tortured responses that one could spend weeks parsing.

The one question that really made me prick up my ears was one from the very ferocious John Mann, MP. It’s around 15:51:00 in the session video (slow to load), and it goes like this:

Mann: …Mr Gulliver, quick one: just whether, with your Panamanian setup, whether Mossack Fonseca was involved, directly or Indirectly?

Gulliver: I have no idea, and actually, that structure no longer exists.

Casually saying “I have no idea”, to John Mann, on this particular subject, might turn out not to have been all that clever.

To understand why, we need, for a start, some more detail on this “Panamanian setup”, for instance, from Bloomberg:

(Bloomberg) — The decision by Stuart Gulliver, the chief executive officer of HSBC Holdings Plc, to park money in Switzerland through a Panamanian company puzzled lawyers who didn’t see a clear tax benefit from the move.

Gulliver said he set up the account with HSBC’s Swiss unit while living and working in Hong Kong for reasons of confidentiality, so that colleagues wouldn’t be able to see how much he earned. He told reporters on a conference call Monday that he closed that account in 2009.

The confidentiality argument makes sense, kind of,

“A Swiss account held in the name of a Panamanian company was not an uncommon structure for some wealthy individuals,” said Mark Summers, a Geneva-based lawyer with the firm of Charles Russell Speechlys. “In this case, it doesn’t look like a structure that a Hong Kong resident, or U.K. non-domiciled resident would have needed. There isn’t an obvious tax advantage.”

…but…

Gulliver, 55, could have chosen less complicated ways of depositing his earnings discreetly, lawyers said.

Choosing another bank would have prevented colleagues from prying into his compensation. Moreover, Swiss financial secrecy laws would have prohibited any of the country’s banks from sharing account data without his permission or a formal legal procedure. Any Swiss banker doing so risks a prison sentence.

Gulliver, located in Hong Kong and serving as Head of Treasury and Capital Markets in Asia-Pacific in 1998, when this structure was set up, explains it thus:

“Being in Switzerland protects me from the Hong Kong staff,” he said. “Having a Panamanian company protects me from the Swiss staff because people are interested in what their colleagues are paid. Why is it Panamanian? That’s the structure that the private bank was putting people into in those days.”

To sum up, tendentiously: in HSBCworld, back in 1998, or earlier, and from then on, until 2009, at least, it was possible to set up bank accounts in such a way that no-one really knew what was going on: not the Swiss staff (nor directors), nor the Hong Kong staff, nor, necessarily, the main board of HSBC, either. Obviously in the particular case of Gulliver, someone would have known where to credit Gulliver’s bonus, but in general, HSBC would have been putting a lot of trust in the folk out in the offshore subsidiaries. So what, then, of any other accounts routinely set up in the same sort of way, according to Gulliver himself, between, say, the mid-90s (or even earlier) and 2009, when Gulliver closed the account (or even later)? Are there any lurking horrors there, perchance?

Here’s one more detail:

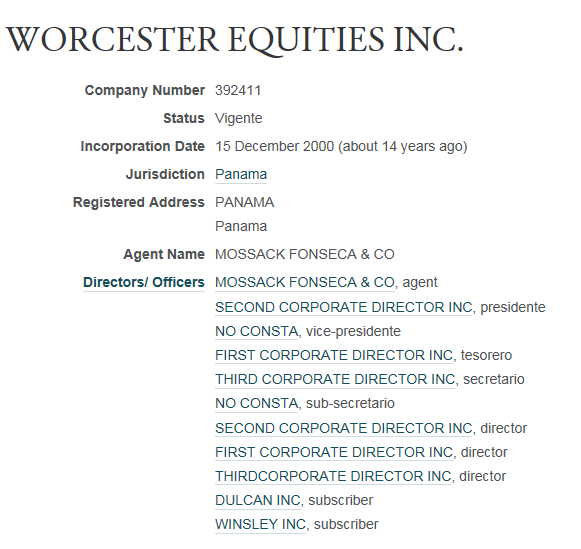

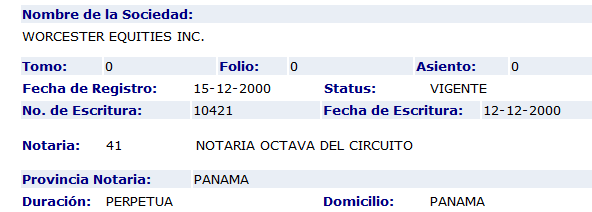

Gulliver’s account was set up in the name of Panama-registered Worcester Equities Ltd., The Guardian reported.

Here are Worcester Equities’ particulars, from the Panama register, via OpenCorporates. Evidently John Mann, MP, is better-briefed about Mossack Fonseca’s involvement than Stuart Gulliver:

As you can see, this is as opaque as it gets: not a single one of the company officers is an identifiable human being.

The differences between Gulliver’s account and the facts portrayed by OpenCorporates prompt further questions.

First, the company was incorporated in 2000, not 1998, and a quick check of the official Panama registry

confirms that OpenCorporates does have the date right. So, if neither OpenCorporates nor Stuart Gulliver’s memory is playing tricks, what was the Gulliver arrangement between 1998 and 2000?

Second, if, as Gulliver affirmed before the Treasury Select Committee “that structure no longer exists”, why is the company still live, five years later? Where are its bank accounts now, and who is operating them?

That’s a question for Mossack Fonseca, of which Gulliver, evidently, has “no idea”. That idealessness matters a lot already, and will soon matter more.

For an inkling of why it matters already, let’s examine some claims made in a December 2014 investigative article at vice.com by Ken Silverstein.

The article is about Mossack Fonseca, and, discouragingly for the oblivious Stuart Gulliver, it is headlined The Law Firm That Works with Oligarchs, Money Launderers, and Dictators. It is unreferenced, but in almost all cases it turns out to be very easy to back-fit confirmation or corroboration from public sources. So I reckon Silverstein’s done all the legwork he says he’s done, and simply stripped out the references for his long Vice piece. I’ll skip the bits I couldn’t stand up; what’s left is unnerving enough. First, there’s the frame:

One purpose of a so-called shell company is that the money put in it can’t be traced to its owner. Say, for example, you’re a dictator who wants to finance terrorism, take a bribe, or pilfer your nation’s treasury. A shell company is a bogus entity that allows you to hold and move cash under a corporate name without international law enforcement or tax authorities knowing it’s yours. Once the money is disguised as the assets of this enterprise—which would typically be set up by a trusted lawyer or crony in an offshore secrecy haven to further obscure ownership—you can spend it or use it for new nefarious purposes. This is the very definition of money laundering—taking dirty money and making it clean—and shell companies make it possible. They’re “getaway vehicles,” says former US Customs investigator Keith Prager, “for bank robbers.”

Then there’s Rami Makhlouf:

Sometimes, however, international investigators are able to follow the money. Take the case of Rami Makhlouf, the richest and most powerful businessman in Syria. Makhlouf is widely believed to be the “bagman”—a person who collects and manages ill-gotten loot—for President Bashar al Assad, who during the past three years has helped cause the deaths of more than 200,000 of his citizens in the country’s civil war.

…

If Makhlouf was a bank robber, his getaway car was a company called Drex Technologies SA. In July 2012, the Treasury Department identified Drex—a dummy entity with a British Virgin Islands address—as the corporate vehicle Makhlouf secretly controlled and used “to facilitate and manage his international financial holdings.” In other words, say Makhlouf had skimmed a few million dollars off the top of a secret business deal with a crooked Syrian official. He wouldn’t put it into a bank account that he could be linked to; instead, he’d funnel it through Drex so the money couldn’t be connected to him.

Silverstein claims that the agent who incorporated this BVI company was Mossack Fonseca. He’s right. Here’s an official EU sanctions list. Scroll down and down to the “entities” section and you will find, at no 48, Drex Technologies SA of the BVI and its agent, Mossack Fonseca.

Next up, Argentinian oligarch Lázaro Báez:

The investigation and court records allege that Báez is the secret owner of more than 100 shell firms that Mossack Fonseca has helped establish in Nevada. All of them were managed by Aldyne Ltd., an anonymous company that Mossack Fonseca registered in the Seychelles Islands, according to prosecutors. (Mossack Fonseca has not been charged to date in either Argentina or Nevada, but one of its operatives in Las Vegas has been deposed in the legal case, and the district court has told the firm to turn over records related to the Báez shell companies, an order with which it has refused to fully comply.)

A former bank teller, Báez built a vast business empire through contracts awarded by his close friends Cristina and Néstor Kirchner, the current and previous presidents of Argentina, respectively, and their political allies in his home province, according to news reports and investigators. Báez was so bereft when his patron Néstor died, in 2010, that he erected a three-story mausoleum to house his remains. Prosecutors allege that the Nevada shells were part of a network that Báez used to move offshore more than $65 million in funds diverted from public infrastructure projects.

Yup, that is indeed the allegation, and there’s some August 2014 Bloomberg coverage to go with it.

The connection to Mossack Fonseca goes via a company incorporated in Nevada, M.F. Corporate Services, directors Marta Edghill and Imogene Wilson. OpenCorporates has MARTA EDGHILL as director of 9,000+ Panamanian companies and IMOGENE WILSON (that form) as director of another 1,400. In each case that I checked, Mossack Fonseca was the Panama agent. I did not check all 10,400 companies. But I do think my sampling was good enough to establish that the Panamanian directors of the Nevada company M. F. CORPORATE SERVICES (NEVADA) LIMITED are professional nominee directors of Mossack Fonseca. It’s the same outfit in a light disguise.

Why is Mossack Fonseca styling itself “M.F.’? Silverstein has a plausible explanation:

This sort of bogus separation is a tactic employed by many big shell-firm incorporators, because it allows the parent company to disavow any connection to its local offices if the shit hits the fan from a legal standpoint. It’s sort of like how Walmart might operate in Bangladesh, distancing itself from sweatshops by long and complex supply chains. (Like Walmart, Mossack Fonseca has never been directly prosecuted for the actions of its affiliates.) “These are seamless, vertically integrated top-down organizations until the minute that a cop or investigator comes along,” says Jack Blum, the money-laundering expert. “Then they disintegrate into a series of unconnected entities, and everyone swears they don’t know anything about anyone else in the system. It’s like a jigsaw puzzle that’s assembled but suddenly falls apart when someone starts investigating.”

Silverstein’s own account of his visit to M.F.’s office, for a little talk with the local director, bears this out. Patricia Amunategui…

runs day-to-day operations, though internal company documents I found in court records show she works closely with Mossack Fonseca employees in Panama, such as Leticia Montoya, the custodian of record for dozens of shell firms linked to Lázaro Báez.

Confronted about the Mossack Fonseca link, she says:

“Give me your name, and I’ll see if our attorney can talk to you,” she said while shaking a finger in the negative.

“The attorney for Mossack Fonseca?” I asked.

“No, my company’s attorney,” she replied, referring to MF Corporate Services. “They’re separate.”

That’s “separate” as in “bogus”. Next, according to Silverstein, there’s Mirror Development Inc, another Mossack Fonseca shell,

which Siemens of Germany employed to funnel bribes to Argentine government officials who helped it win a $1 billion contract to produce national identity cards.

Reuters agrees; the DoJ overview is here; Mirror Development Inc duly appears in the indictment. So far, there are mixed results for the defendants:

The SEC appears likely to reach three settlements, including Truppel’s, and to win default judgment against two others. A federal judge in February dismissed charges against another defendant on jurisdictional grounds and the SEC withdrew its complaint against a seventh in October.

The results are mixed indeed: some of the defendants, and new ones, now face more charges, in Argentina.

Lastly, (I am leaving a few loose ends that hardly make much difference to the overall vista of horror), and paraphrasing and hyperlinking, Silverstein has yet more connections to Mossack Fonseca:

Billy Rautenbach, an alleged bagman for Robert Mugabe, the Zimbabwean despot, via Rautenbach’s company Ridgepoint;

Yulia Tymoshenko, former Ukrainian prime minister, accused of participating in a ‘Massive’ bribery scheme, with another Mossack Fonseca company, Bassington Ltd, right at its heart, and another Swiss bank, Credit Suisse, implicated.

Beny Steinmetz, an Israeli billionaire who, Global Witness alleges, used offshore shell firms to pay a bribe to a wife of the homicidal dictator of Guinea, where Steinmetz was seeking (and subsequently got) a huge mining concession. Steinmetz tried, and failed, to use the UK’s Data Protection Act in an attempt to muzzle Global Witness, a forlorn gambit. Happily, then, you can still read how the BVI shell company Pentler, heavily involved in the Steimetz story, and its apparent owner Onyx Financial Advisers, were both incorporated by Mossack Fonseca (PDF). Another faceless BVI company that is part of the plot, Magali, has the same BVI address as Mossack Fonseca & Co (BVI).

It’s nice work by SIlverstein, putting that lot together.

In short, Mossack Fonseca are in it up to their thighs, and Stuart Gulliver has “no idea”.

Amazingly, it’s now quite likely to get even worse. On the very same day that Gulliver put in his tense appearance at the Treasury Select Committee, the Süddeutsche Zeitung had this (my English):

-

The Mossack Fonseca Group, of Panama, is a well known provider of shell companies used by tax dodgers and other criminals

-

Investigators from the USA and other states have obtained the firm’s internal documents. Other countries are interested. German tax investigators have bought data relevant to Germany. On the basis of the documents, they are now carrying out raids.

-

The various groups of officials are operating with selections of firm’s records. Süddeutsche Zeitung has all of the data in the internal Mossack Fonseca documents at its disposal, more than 80 Gigabytes. Full evaluiation of the data is nowhere near complete.

There’s more:

Thousands of shell companies, registered in the Seychelles, the Bahamas, the British Virgin Islands or in Panama, built by Mossack Fonseca Group, ordered and paid for by Banks, wealth managers and lawyers from dozens of countries, can be found in the secret data on the USB sticks.

…

Clearly, Mossack Fonseca has a problem.

Onlookers can only agree.

It’s a spectacular disaster. If, like Mossack Fonseca, your entire business model is predicated on secrecy and deniablity, a massive data leak, including gigabytes of emails, is the one thing that could kill you stone dead.

Mossack Fonseca are likely to find out if it’s that bad in the coming months. HSBC and other banks, such as Credit Suisse and Commerzbank (summarizing the German: big tax investigation sparked by the Mossack Fonseca leak), will also have a problem.

For it just so happens that one of the authors of the SZ piece, Bastian Obermayer, is with the ICIJ. This Panama story looks like a natural for one of their leaks series. In fact the current ICIJ “Swiss Leaks” series, featuring HSBC, was the main reason why its execs were suddenly hauled in front of the Treasury Select Committee. Given HSBC’s fondness for the Panama connection, 1998-2009 at least, I can’t help wondering if there will be a Panama Leaks series soon, and a repeat appearance by Stuart Gulliver before the TSC. I’m pretty sure that even he will have heard of Mossack Fonseca, by then.

Back to Silverstein for one last grisly thought:

Documents and interviews I’ve conducted also show that Mossack Fonseca is happy to help clients set up so-called shelf companies—which are the vintage wines of the money-laundering business, hated by law enforcement and beloved by crooks because they are “aged” for years before being sold, so that they appear to be established corporations with solid track records—including in Las Vegas. One international asset manager who talked to Mossack Fonseca about doing business with them told me that the firm offered to sell a 50-year-old shelf company for $100,000.

That’s a cue for more speculation: Gulliver, at his next TSC appearance, might have more to say about who’s been using his still-registered Mossack Fonseca company, Worcester Equities Inc, since his minions kicked it back to Mossack Fonseca in 2009. Failing that, the ICIJ may enlighten us about who’s running Worcester Equities now.

Unfortunately for HSBC, that’s nowhere near the end of the horrors. Look out for further parts in this series.

Reading your fine work about garden variety crooks like “The Blue Flash” is almost entertainment in and of itself. Reading about the same sleazy behaviour being engaged in by Big Banks and Legacy Financials crosses some sort of line. Now it’s not so much enjoyable, (despite the grief it has brought to countless ‘suckers,’) as depressing and enraging. Here’s hoping that the Hon. Mr. Mann has his ‘shining armour’ on.

Gulliver’s Travails?

Us mopes can only shake our heads ruefully at the ingenious and disingenuous sweep of arrogance, and at all the stuff that’s being done to us with the fundamental wealth we work so hard to generate (and, day by day, work so much harder and longer for the same quantum) that leverages all this froth.

Can I underscore one bit of the text?

“Swiss financial secrecy laws would have prohibited any of the country’s banks from sharing account data without his permission or a formal legal procedure. Any Swiss banker doing so risks a prison sentence.”

What you so matter-of-factly and adroitly report on here is just more mass, another straw, as it were, added to the load, that already includes other heavy items like “carried interest.” All summing into the sense of hopelessness and oppression and building rage that might lead to the next Bastille Day or global meltdown.

But it is so very interesting that bankers actually apparently fear criminal sanctions. Of course, in FunnyMunnyLand, the punishable behaviors that actually might lead to prison sentences appear limited to ratting out (“sharing account data”) fellow thieves, or stealing from each other (Madoff), stuff like that. All else is plausibly deniable and compartmented. Too bad the “regulatory apparatus” (which the Madoff game and my own federal-regulatory experience indicates includes so many young fresh faces looking for positions with the “regulated entities” or their enablers) is not even close to being up to the task of minimally slowing the disease processes.

Any indications that our State Security types and spooks are also players in this particular little game? Harking back to prior blowback-inducing leaks from inside the Dark Side?

In his book ‘ Keynes Hayek ‘ Nicholas Wapshott quotes Hayek as saying ‘ There is probably no single factor which has contributed to the prosperity of the West than the relative certainty of the law ‘ so when one reads a piece like this one is forced to conclude that that ‘ factor ‘ is being undermined by these shenanigans which extend well beyond any conceivable test of making reasonable provision for the protection of their wealth by the individuals concerned . It can far more easily can be seen in the context of Bill Black’s ‘ control fraud ‘ or looting by CEOs of large financial institutions . And given the fact that these same institutions are so fundamental to the everyday financial dealings of the rest of us, and how, with their presence on every high street, they seek to proclaim their integrity and propriety the question arises, at what point do enough of us wake up to the reality behind the facade and say like Greg Wise and Emma Thompson did recently enough is enough – jail them . Not anytime soon I hear you say; we are more likely to see a collapse of sufficient proportions to bring down the whole rotten edifice because our law enforcers have also seen fit to absolve themselves of any responsibility for upholding the law when money speaks louder than words.

Absolutely agree John.

Lawyers talk of lifting the corporate veil but its absurdly uncertain and unlikely of success.

The fact is, to the best of my knowledge, it was shipping companies and later airlines who sought for a way to continue in business whilst evading actions for damage to cargo and injury to passengers. Their initial answer was a flag of convenience and then the fuller utility of undisclosed ownership became apparent and everyone with a dodgy dollar went for it. Please correct me if I am wrong.

Random observations, triggered by the post and John Hope’s and others’ comments:

As I understand it, the hated “Sharia Law” outlaws collecting interest on lent money and otherwise kneecaps most of the fundamental practices of Western financialization, which might account for a significant portion of Nativist America’s hatred of it. An interesting discussion by people deep in the culture: http://www.quora.com/Why-is-charging-interest-usury-forbidden-in-Islam Which makes it clear that there are “jailhouse lawyers” in Muslim lands too.

My Econ 101 professor (as far as I could go) referred in passing to what he called “slack” in that seemingly elegant system where supply and demand curves cross and rule everything that matters. He meant the reality of what is “the economy,” which he understood more in the old sense of “political economy,” the sum of all the transactions and beliefs that sum into “the economy” which is of course a lot more than theory and rules. And noted that a good part of it all depends on “a jovial corruption,” which ought to be a band on its own graph that plots baksheesh against instability and delimits the tolerable scope of an irreducible presence. It’s one thing to pass a thousand pesos or a dozen Euros to an official who “legally” can veto your visa or exit papers, or hand a $20 or $50 over along with your driver’s license to the radar cop. Another to be Goldman Sachs, and the NY FED, and the guys who put the fix into LIBOR, and so many other bleedings. Still another thing to conceal your knowledge that your new $10 billion-in-potential-sales-protected-by-patent medication will kill a lot of people before the regulators and tort lawyers catch up with you, by which time “IBG-YBG” of course.

“Slack” is mandatory in any mechanical system, where “perfect fits” lead to gears that won’t turn at all. Engineering drawings and shop manuals specify play and clearances and what to use for lubrication. So to record a Torrens title certificate in Chicago, you put a slick $50 bill between the inner joints of your middle and ring fingers, so when you “shake hands” with the desk clerk it can lubricate the process, which otherwise can result in “lost documents” or delayed recording. And more than one attorney, thanks to other handshakes with judges he knows, has been known as “The Miracle Worker” by criminal defendants. The FBI, that grumpy J. Edgar-corrupt purveyor of rectitude, bragged about one of its more successful actions, Operation Greylord: http://www.fbi.gov/news/stories/2004/march/greylord_031504 The 2004 FBI press release text is so smug and ironic it ought to be shared:

Today marks an important anniversary in the annals of public corruption investigations in the United States.

Twenty years ago today, in a federal courtroom in Chicago, a jury found Harold Conn (top center in photo) guilty on all 4 counts of accepting bribes to be passed on to Cook County judges as payment for fixing tickets. The evidence? He had been caught live on FBI tapes.

This “bagman” had been Deputy Traffic Court Clerk in the Cook County judicial system, and he was the first defendant to be found guilty in a mammoth sting investigation of crooked officials in the Cook County courts.

It was called OPERATION GREYLORD, named after the curly wigs worn by British judges. And in the end—through undercover operations that used honest and very courageous judges and lawyers posing as crooked ones… and with the strong assistance of the Cook County court and local police—92 officials had been indicted, including 17 judges, 48 lawyers, eight policemen, 10 deputy sheriffs, eight court officials, and one state legislator. Nearly all were convicted, most of them pleading guilty (just a few are shown in our photo). It was an important first step to cleaning up the administration of justice in Cook County.

That’s really the whole point. Abuse of the public trust cannot and must not be tolerated. Corrupt practices in government strike at the heart of social order and justice. And that’s why the FBI has the ticket on investigations of public corruption as a top priority.

How’d that happen? Historically, of course, these cases were considered local matters. A county court clerk taking bribes? Let the county handle it.

But in the 1970s, state and local officials asked for help. They didn’t have the resources to handle such intense cases, and they valued the authority and credibility that outside investigators brought to the table. By 1976, the Department of Justice had created a Public Integrity Section, and the FBI was tasked with the investigations, focusing on major, systemic corruption in the body politic.

Who’s investigated? Public servants: members of Congress and state legislatures; members of the Administration and governors’ offices; judges and court staffs; all of law enforcement; all government agencies. Plus everyone who works with government and is willing to pay for “special favors”: lobbyists, contractors, consultants, lawyers, U.S. businesses in foreign countries, you name it.

What kind of crimes? Bribery, kickbacks, and fraud. Vote buying, voter intimidation, impersonation. Political coercion. Racketeering and obstruction of justice. Trafficking of illegal drugs.

How serious of a problem is it? Last year the FBI investigated 850 cases; brought in 655 indictments/informations; and got 525 who were either convicted or chose to plead.

Last words: Straight from Teddy Roosevelt: “Unless a man is honest we have no right to keep him in public life, it matters not how brilliant his capacity, it hardly matters how great his power of doing good service on certain lines may be…No man who is corrupt, no man who condones corruption in others, can possibly do his duty by the community.” [emphasis added]

Harrrumph. Ahem. Yeah. Thus it is written, thus it will be. Despite occasional “enforcement” efforts over decades, “handshakes” by the cynically immune, protected by the mythologies they project from behind their screen of impunity, are the norm. Too bad that death by metastatic cancer is so, ah, unpleasant, for the host, but seems to be the inevitable fate…

Why would this possibly be a “nightmare” for HSBC, it will have absolutely no impact on them. Wrist slap fine, some org chart shuffling, zero jail time for the criminals.

Two-tier legal system, one for the rich and connected, another one for you and me.

Well, given the sudden profusion of leaks, you should definitely consider the possibility that something quite different is going on.

There’s a hint about what that might be here: http://www.businessinsider.com.au/herve-falciani-reveals-secret-organisation-behind-hsbc-leak-2015-3 .

That’s totally unconfirmed for the moment, and possibly never to be confirmed; but let’s see how the story develops.

HSBC is safe from prosecution in USA. James Comey FBI director joined HSBC Holdings Board of Directors in 2013. They are protected by Great Britian and US governments.

Hey,bankers are not considered criminals when they break the law. No, they are just fined for getting caught. Isn’t collecting large fines just another way for government agencies to fund their operations and at same time look like cops?

Just to be clear, Comey was at HSBC before FBI, (for all the difference that makes…).

Some back story here:

http://www.forbes.com/sites/francinemckenna/2013/05/31/james-comey-and-kpmg-isnt-it-ironic/

Another interpretation of what fines would constitute would be brides to get off.

Fine reporting indeed. Now trusting an institutional system, which has been systematically captured for the last 4 decades, to hold it’s own to account is altogether another thing. If history is any guide, the elephants will continue fighting while the grass gets trampled.