By Simone Tagliapietra, Senior Researcher at the Fondazione Eni Enrico Mattei in Milan and Visiting Researcher (Non-residential) at the Istanbul Policy Centre at Sabanci University in Istanbul, and Georg Zachmann, a member of the German Advisory Group in Ukraine and the German Economic Team in Belarus and Moldova. Cross-posted at Bruegel

Just a week after having sent a Statement of Objections (SO) in the frame of the antitrust case against Google, EU Competition Commissioner Margrethe Vestager sent yesterday an SO in the frame of the case against Gazprom. The decision to send a charge sheet against the Russian gas company came after almost three years of investigations, which have also seen EU antitrust officials raiding Gazprom offices in central and eastern European countries.

But what is this antitrust case all about? And, considering the current EU gas market environment, has it arrived at a good time or bad time for Gazprom? Furthermore, what might be its potential impact on overall EU-Russia relations? This blog post aims to shed some light on these issues, also by trying to consider the perspective that Gazprom might have on the issue.

The case in a nutshell

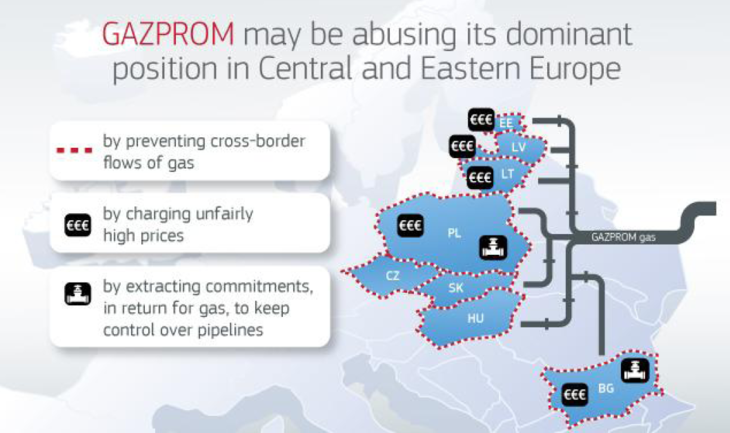

In the Statement of Objections sent yesterday, the European Commission alleges that in the Baltic countries, Bulgaria and Poland Gazprom is:

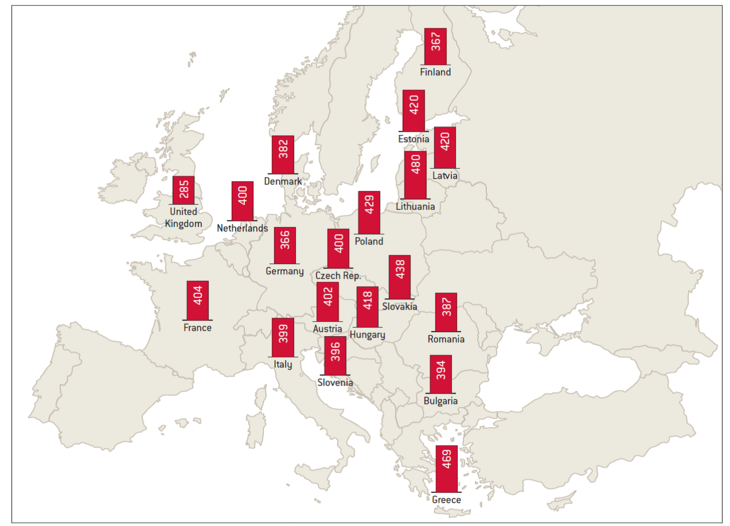

i) Hindering cross-border gas sales, through certain clauses in the contracts with its customers allowing Gazprom to charge higher prices in countries that are more dependent on Russian gas (see map).

Average price for Russian gas in 2013 in EU member states, USD/thousand cubic meters

Source: Bruegel based on Henderson and Pirani (2014).

ii) Charging unfair prices through Gazprom’s pricing formulae.

iii) Making gas supplies conditional on obtaining unrelated commitments from wholesalers concerning gas transport infrastructure. Specifically, the Commission’s preliminary view is that Gazprom made wholesale gas supplies in Bulgaria conditional on the country’s participation in the South Stream pipeline project, and in Poland conditional on the company’s control over investment decisions concerning the Yamal pipeline.

Gazprom has 12 weeks to respond to the Statement of Objections and also has the opportunity tocall an oral hearing to make its defence. As there is no legal deadline for the Commission to complete antitrust inquires into anticompetitive conduct, the duration of the investigation is uncertain. If it keeps to legally binding commitments that address the Commission’s concerns, it will still be able to settle the charges. Otherwise, the Commission might decide to issue an infringement decision and ultimately fine Gazprom up to 10 percent of its global annual turnover.

The EU antitrust case against Gazprom

Source: European Commission.

The case in the context of the current EU gas market environment: good timing

But does this case arrive at a good time or a bad time for Gazprom? Paradoxically, looking at the current EU gas market environment it might well be argued that the case arrives at a rather favourable moment for the Russian company, at least for two reasons: demand outlook and pricing evolution.

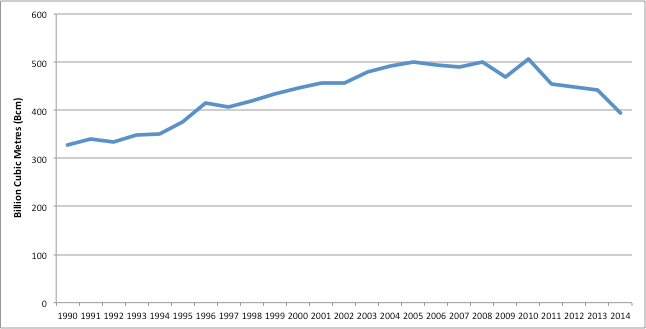

When discussing the current status of EU gas demand, energy analysts often use expressions like “nightmare”, “disaster” and “disruption”. These words provide a good sense of the sharp downward trend that has characterized EU gas demand since 2008, not only due to the recession but also to the increasing share of renewables in power generation, increasing energy efficiency and the comparative advantage of the United States in terms of gas prices. As a pivotal supplier, Gazprom is also partly responsible for this ‘demand destruction’ in Europe, as its pricing policy was not flexible enough to ensure the inter-fuel (vis-à-vis coal) and international (vis-à-vis the US) competitiveness of its clients. The 10 percent reduction in EU gas demand between 2013 and 2014 illustrates the massive size of the issue.

Evolution of European gas demand (EU+CH) from 1990 to 2014

Source: Bruegel elaboration on British Petroleum and Eurogas.

With the unanticipated fall in demand, market power in the EU has rapidly shifted from producers to consumers. Gazprom might seize the opportunity presented by the antitrust case to revise its business model in the EU, with the aim of enhancing its competitiveness in the market and thus securing both the integrity of EU gas demand and its share in that.

The shift in market power from producers to consumers is connected to the pricing issue. As an overall trend, European gas pricing is evolving towards a hub-based system for commercial and regulatory reasons. This process is still in the making, considering that long-term contracts have not been terminated yet, but it is certainly advancing rapidly. Some companies, such as Statoil, have already adjusted their business model to the new reality of the EU market. Gazprom should have already followed this example, by adjusting its pricing formulae according to new market conditions, always with the ultimate aim of securing its segment of the EU gas demand. Such a move would have been particularly reasonable in recent months, considering the unprecedented fall in oil prices, which has already started to cut into Gazprom’s oil-indexed contracts and which will consistently lower these gas prices during – and probably even beyond – 2015.

Evolution of Brent oil price from January 2000 to March 2015

Source: Bruegel elaboration on Energy Information Administration.

In this context, it might well be argued that the EU antitrust case arrives at a rather good moment for Gazprom, as it might seize this opportunity to enhance its business model in the EU and thus secure its long-term sustainability.

However, Russia perceives the EU antitrust case as mere political action. It will thus most likely use it as a rallying point and adopt a position that serves neither security of supply nor security of demand in the EU. This risk is reinforced by the fact that the EU antitrust case arrives at a very bad time for overall EU-Russia relations.

The case in the context of current EU-Russia relations: bad timing

Commissioner Vestager declared last February that “If you see [the EU antitrust case against Gazprom] as a political case then any timing will be bad”. This affirmation does certainly make a lot of sense, but of all the possible timings, the current one seems to be particularly bad for EU-Russia relations.

In fact, current political relations between the two players are extremely difficult, due to the convergence of a variety of factors such as EU sanctions against Russia over the Ukraine crisis, diplomatic efforts of Russia to unhinge the precarious EU “single voice” in foreign policy by attracting vulnerable EU Member States into its economic orbit, the persistency of tensions in Eastern Ukraine even after the Minsk II agreement, and the difficulties of the ongoing trilateral EU-Ukraine-Russia gas talks and related security concerns.

In this extremely complex geopolitical situation the EU antitrust case against Gazprom will most likely – in this case literally – add fuel to the fire.

Conclusions

In commercial terms Gazprom might benefit from the EU antitrust case, in the sense that it might provide the necessary outside impetus for Gazprom restructure its business model in the EU accordingly to new market realities, in line with actions already taken by other EU gas suppliers such as Statoil. Such a process will enable Gazprom to sustain its role in the European market in the long-term, and also contribute to de-politicize the role – and the perception – of the company in Europe. Moreover, such a process might also help Gazprom to become de-politicized within Russia, making it less likely in the future that sensible business decisions are overruled by political concerns.

However, political arguments will most likely prevail over commercial ones, and this dynamic will further worsen the already deteriorating EU-Russia gas partnership. If Gazprom does not collaborate with the European Commission during the case, it will provide the EU with another argument in favour of diversification of gas supplies, ultimately contributing to the further deterioration not only of the EU-Russia gas partnership but also of the position of Gazprom itself in the EU. At this moment, as Belyi and Goldthau also point out, Gazprom should decide on whether to follow a risky political path or a sustainable commercial trajectory. In the latter case, its actions might ultimately contribute to the (re)construction of a relationship of mutual trust between the EU and Russia, which could expand far beyond the realm of the gas market.

The Eurozone ought to consider the possibility that Russia stops selling energy to it at any price.

They don’t have any leverage here…they threw it all away by siding with US hegemony over Ukraine’s coup.

Those poor defenseless NATO countries…

I’m very much a fan of regulating anti-competitive behavior, but this notion that Russian gas supplies are some isolated economic matter is hilarious. The Europeans have to decide whether they are sovereign nations or vassals of the Anglo-American empire.

Here’s a little high school reading help for the commission:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Enlargement_of_NATO

I have often wondered what kind of backhanded threats Norway was given to get them to be a founding member.

This in light of how unlike on the continent, the Soviet forces up north pulled back once the German capitulation was complete.

Slightly off topic, but have you seen this? Cracks me up every time.

http://www.africafornorway.no/

If one starts with the presumption that everything is business as usual, this article makes some sense. If, however, one starts with the presumption that the United States has hijacked the EU (Brussels) bureaucracy and that the EU (Brussels) is a US vassal, the entire issue ceases to be about economics and becomes political–US attempts to crush independent Russia. If political, Russia should indeed ask each of the ‘affected’ countries one simple question: Do you want to honor our pre-existing contracts or not. If you breach existing contracts we will act as would anyone to a willfully breaching counter-party. We will end our supply forthwith.

Will this win Russia any friends? Probably not, but with friends like the EU, who needs enemies. Vladimir Putin is a better man than I am but I would say, “Let them freeze in the dark.”

“German Advisory Group in Ukraine and the German Economic Team in Belarus and Moldova”

So the authors are in the camp decidedly opposite Russia, and state that if Gazprom caves in to the requests of the EU it will ultimately be great for Gazprom? And that this will “make it less likely in the future that sensible business decisions are overruled by political concerns” — this is riotous, given the self-inflicted economic wounds caused by the politically-motivated EU economic sanctions on Russia.

All right, there are a few aspects that I do not get:

1) The authors claim that Gazprom has a long-term sustainability problem, and that the EU may diversify its gas supplies. How exactly? The only possible long-term diversification in sufficient amounts is by importing gas from Iran — and this requires quite a number of political, technical and commercial stumbling blocks to be cleared beforehand.

2) The authors talk about “the comparative advantage of the United States in terms of gas prices”. First of all, I am sure they mean a competitive advantage not a comparative one. The second point is that shale production was possible because of extremely high prices of gas and oil — and is now in serious trouble. How does this exactly jibe with a supposed competitive advantage against easier and cheaper to extract Russian gas?

3) The whole argument is based on market conditions favouring buyers, and inflexible, high prices from Gazprom ultimately leading to less demand for its production. Hence, Gazprom should revise its pricing formula to keep its market share, and this would have helped it counteract the price drop caused by its current oil-indexed formula. Wait, isn’t there a contradiction somewhere? Does the current pricing formula of Gazprom lead to too high prices or to too low prices?

So, I find the whole argument a bit confusing.

I’m completely confused by this. Gazprom is a state owned company from outside the EU. This isn’t Microsoft or GE. Is this just a case of U.S. puppets not grasping the difference between reality and economics? Gazprom can do whatever the hell it wants until the EU comes up with a better alternative which isn’t going to be trans-Atlantic despite the fantasies of frackers.

The price is negotiated by heads of state not insignificant bureaucrats. This whole event is a sham probably run by CIA nitwits.

Iranian gas will go east- to Pakistan and eventually India. Bigger markets, less politics, better pricing.

It will as a result also lessen hostilities between those two.

US shale oil riding to the rescue?

What’s wrong with nc?. First W.Richter’s article on ‘extortionist’ Greece and now this one on Gazprom ‘abusing their dominant role’. Who opened the door here to the ‘Eurocrats’?