Dave here. I’m not sure I agree with the entirety of this take, but it has good data and gives a decent overview of what some economists are saying about China. It’s clear that there’s a leveraging problem in the economy.

By Alicia Garcia Herrero, a Senior Fellow at Bruegel and a non-resident research fellow at Real Instituto El Cano. She is also adjunct professor at City University of Hong Kong and Hong Kong University of Science and Technology (HKUST) and visiting faculty at China-Europe International Business School (CEIBS). Cross-posted at Bruegel.

China’s market drama started in June this year with the collapse of the Shanghai stock exchange, followed by frantic interventions by the Chinese authorities. As if the estimated $200 billion already spent on propping up stock prices were not enough, China found itself in another battle with the market, defending the RMB against depreciation pressures after the PBoC devalued the RMB by nearly 2% on August 11. The cost of the foreign exchange intervention to keep the RMB stable is estimated at $200 billion.

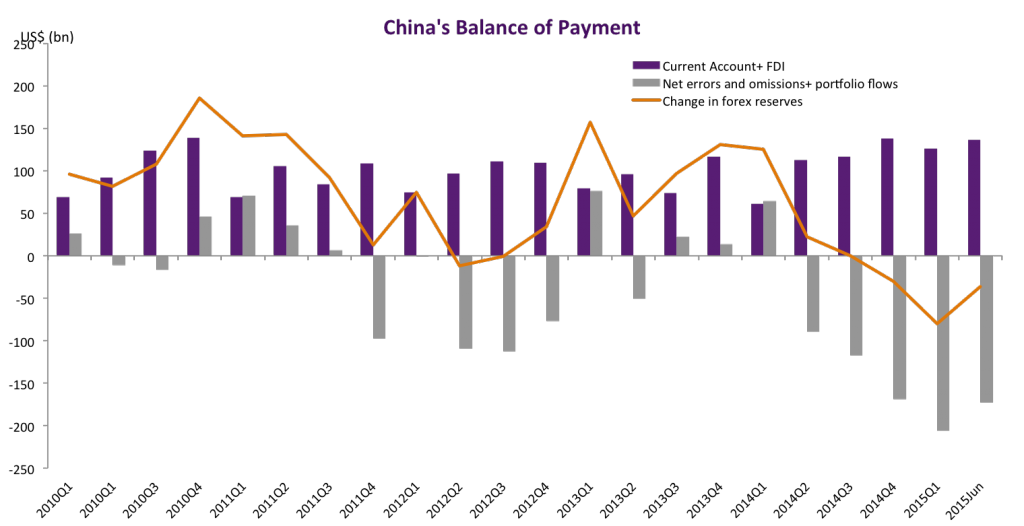

This adds to existing pressures on China’s international reserves, which though still extensive, have been reduced by as much as $345 billion in the last year, notwithstanding China’s still large current account surplus and still positive net inflows of foreign direct investment (Graph 1). The fall in reserves is not so much due to foreign investors fleeing from China but, rather, capital flight from Chinese residents. Another –more positive reason – for the fall in reserves is that Chinese banks and corporations, which had borrowed large amounts from abroad in the expectation of an ever appreciating RMB, finally started to redeem part of their USD funding while increasing it onshore. While this is certainly good news in light of the recent RMB depreciation, the question remains as to how much USD debt Chinese banks and corporations still hold and, more generally, how leveraged they really are a time when the markets may become much less complacent, at least internationally.

Figure 1 – China’s Balance of Payments

Public and corporate sector over-borrowing can be traced back to the huge stimulus package and lax monetary policies which Chinese economic authorities introduced during the global financial crisis in 2008-2009. A RMB 4 trillion investment plan focusing on infrastructure was deployed, but the real cost spiralled. The government also subsidized the development of several important industries and lowered mortgage rates to boost housing demand. At the same time, the PBoC substantially loosened monetary policy with interest rate cuts, reductions in reserve requirements and even very aggressive credit targets for banks.

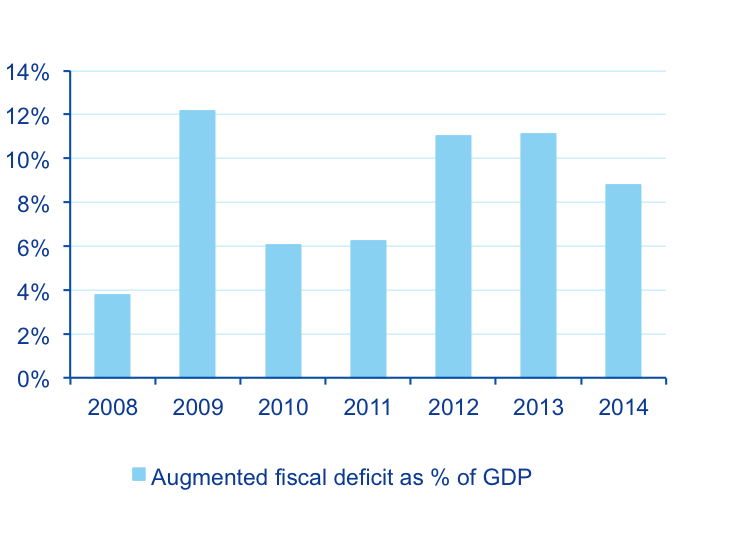

According to the authorities’ initial plan, the funds needed for the stimulus package would come from three sources: central government, local governments, and banks, with costs shared relatively equally. However in practice, given their limited fiscal capacity, local governments had to turn to banks to meet their borrowing needs. Banks could not decline loan requests from central or local government because of government ownership and control over most banks. In the meantime, government subsidies for specific industries boosted credit demand as firms in these sectors sought to take advantage of policy support and expand their production capacity. Mini-stimulus packages have since become the new norm of China’s economic policy. When growth started to slow in 2012, the authorities responded by rolling out more infrastructure projects to revive the economy, which has blotted China’s consolidated deficits every year since 2008. Although no official statistics exist on this, our best estimate is 8-10% fiscal deficits with the corresponding increase in public debt every year (fig. 2).

Figure 2 – China’s augmented fiscal deficit as % of GDP

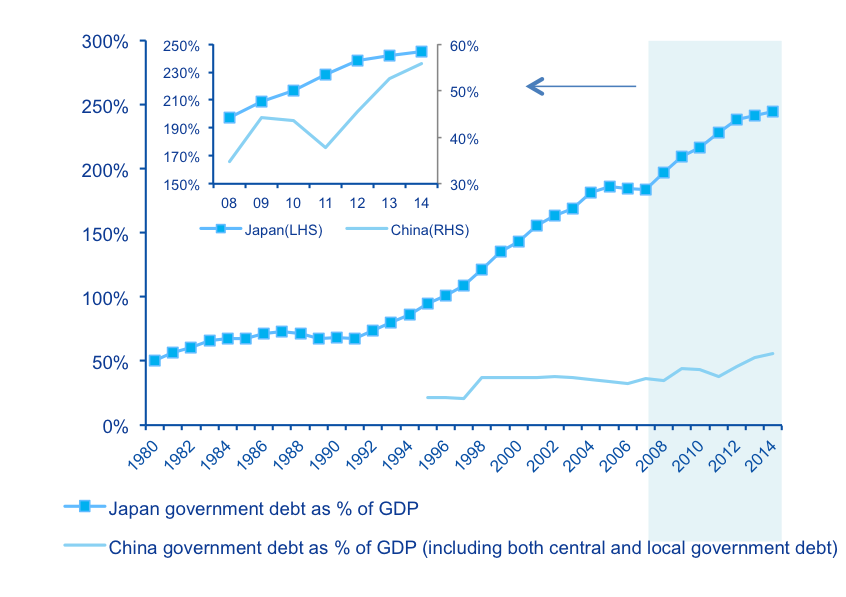

All in all, China’s public debt today is above 53% of GDP, according to the National Audit. This may look small by international standards, especially in the developed world, but the rate of debt growth is unmatched elsewhere, and is even higher than Japan with its recurrently large fiscal deficits (fig. 3).

Figure 3 – Government debt in China and Japan

On the corporate side, cheap money at home made it very – if not too – easy for companies to borrow. In fact, corporate debt has doubled as a percentage of GDP in the last 14 years. Beyond the stock of debt, its service is becoming an issue for corporations as the Chinese economy decelerates and their revenues are on the wane. Taking a very simple measure of stress in debt service, the ratio of EBITDA to interest expense has been below 1 for about one third of Chinese domestically-listed corporates, implying that their operating cash flow was insufficient to service their interest payments. This is especially the case for private ones (fig. 4).

Figure 4 – Corporate debt stress ratios

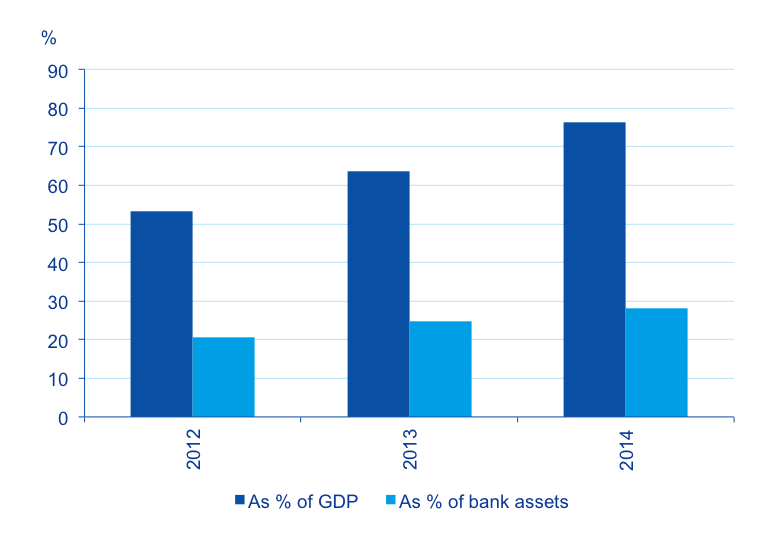

Given that banks’ balance sheets have not been able to accommodate the borrowing from both the public and the private sector, a significant share of the corporate sector, especially smaller corporations, has increasingly used the shadow banking sector to meet their financing needs and circumvent tightening regulations on bank loans (Graph 5). This hardly regulated part of the financial sector now constitutes nearly 30% of GDP, with a good amount of inherent risk.

Figure 5 – Shadow banking has become an important source of financing

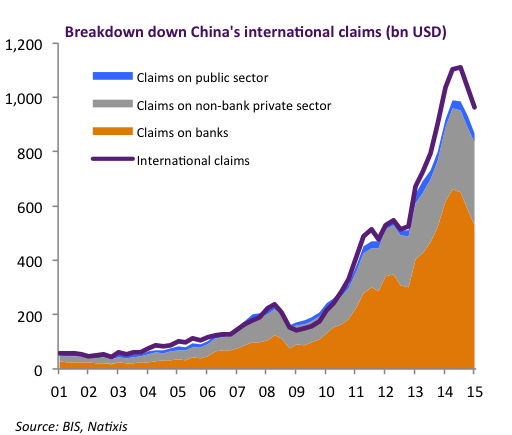

By the same token, the FED quantitative easing coupled with a cheap dollar and the expectation of continuous RMB appreciation made it even easier to borrow from overseas and, to a large extent, from international banks. In fact, the exposure of Chinese banks and corporates to dollar debt has ballooned in the recent years, only correcting very recently in anticipation of FED hikes and the recent RMB depreciation, as previously mentioned (Graph 6).

Figure 6

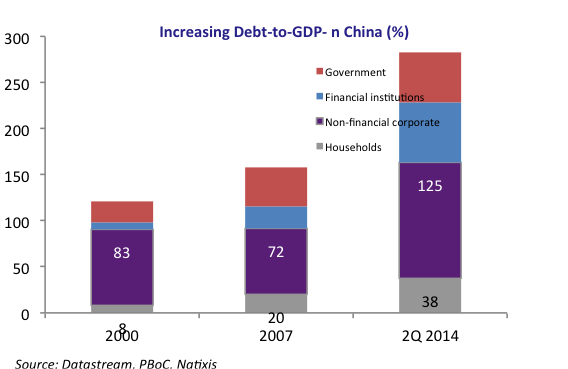

Finally, even households have not been totally spared from the leveraging mania. This can be explained by the fact that they have been confronted with an ever more expensive housing market and, more recently, the possibility to hedge massively to invest in the stock market. All in all, China’s total debt was 284% of GDP a year ago and, given the still large fiscal deficits and the leverage-fed stock market bubble – it seems likely that it may have reached 300% of GDP today.

Figure 7

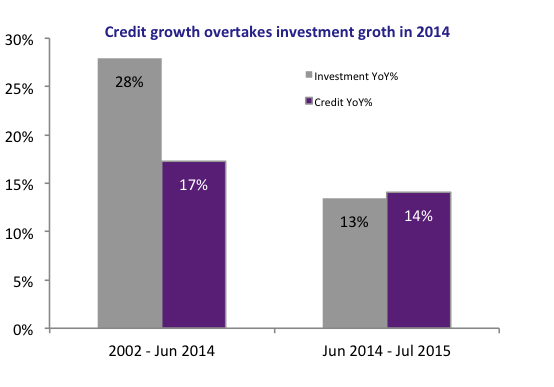

Notwithstanding its massive size compared with other emerging economies, the fact that most of it is domestic has been the key argument for the Chinese government and many economists to downplay the risks. There are, however, at least two main reasons why we should worry about China’s debt. First of all, even domestic debt has to be paid if you want to avoid huge distributional effects. In particular, local government debt will need to be cleaned up at some point, which will worsen banks’ asset quality unless the current loan for debt swap program is extended massively, which then pass the burden on the central government. Second, and more importantly, excessively high debt is known to slow growth. The underlying reason is that every unit of new credit has a harder time in finding a productive project to invest in as those which were more productive have already been funded. In fact, as Graph 8 shows, in the past the Chinese economy needed much less credit for a single unit of investment than it needs now.

Figure 8

On this basis, it seems clear that China can no longer use the old recipes to stimulate its economy. This would only induce additional leveraging and China needs just the opposite. Deleveraging will be painful in the short term, as investment will have to come down even more than it has already. But then wasn’t rebalancing towards a consumption-based model what China really wanted and needed? I would advise the Chinese authorities to forget about more fiscal and monetary stimulus, and push towards deleveraging: better more pain now for more sustainable growth later.

Is this a trick question? I mean expanding credit from $8T to $28T in 15 years…um did people expect they could just bloat credit another $20T or something? Just another malodorous malivestment “boom” driven by the insane CB priesthood (cue MMT’rs explaining why it’s different this time…)

MMT isn’t pro asset bubbles, that’s a straw man. Household and corporate debt =/= sovereign debt. That is the MMT rallying cry. Why misrepresent a simple truth?

I would love to see more discussion of the Chinese economic policy in terms of MMT dynamics.

In particular, it would be interesting to log evidence of MMT influence among Chinese economic policy-makers, or lack thereof.

Given the added government controls, it might be easier to discern trends than in other contexts.

The piece was well written, with helpful data, concise narrative, and normative prescription.

The final recommendations are sound, but I strongly suspect the Chinese government has now become utterly addicted to loose money to boost the economy. This just pushes the problem into the future and makes it bigger and bigger. I’ve no proof, but I strongly suspect that the reason the government so mishandled the stock market crash was not because it didn’t understand that it would be good to let it rebalance, but because so many government and oligarch insiders had got themselves caught short. When you have a situation like this, it becomes politically impossible even for an autocratic society to make the hard decisions.

Another issue is that in contrast to Japan in the 1980’s (and the comparisons are all too obvious), there is not just a shadow banking system, but a shadow-shadow banking system. Anecdotally, there seems to be a huge number of informal lending arrangements in every Chinese town and city, pretty much making everyone a banker. A serious slowdown could cause huge instability as everyone suddenly realises that the apartment or shares people have been using as collateral, are worthless, or have been used as collateral for multiple loans.

A further problem I think is that the Chinese economy seems prone to inflation – this will make monetising the debts a lot harder, in contrast to Japan. Japan seems to have an almost infinite capacity to monetise debt, I really doubt this is the case for China (although perhaps some MMT people might disagree, I’m no expert on this).

So it seems that the Chinese government looked at Paul Krugman’s early-2000s advice to Mr. Magoo to the effect of ‘the Fed needs to blow a housing bubble to mitigate the effects of the implosion of the dotcom bubble’, saw how well that worked out for us a few years down the road, and then decided that the problem was not that the strategy of blowing serial asset-price bubbles of ever-increasing size and ever-deeper entwinement with the real economy was flawed, but rather that the Fed simply didn’t commit to it sufficiently. Not a problem in what, despite all the ‘modern, liberal free-market’ trappings is still largely a command and control system where, when the government mandarins say ‘banks must increase lending’, by golly, banks must increase lending.

So now in the wake of the GFC we have witnessed the Chinese central bank blowing the mother of all credit bubbles to mitigate the effects of the implosion of the US (and European, following our lead) housing bubble which the Fed blew to mitigate the effects of the implosion of the dotcom bubble which the Fed blew before that to mitigate the effects of the Greenspan-feared Y2K catastrophe which never materialized. It’s like a financial-bubble version of one of those Russian matryoshka dolls.

In these discussions I think it’s useful to keep in mind the notion of a failed state.

The Fund for Peace maintain an index of failed states that uses thirteen criteria to determine a state’s relative failure. They look at demographic pressure, massive population movements, legacies of vengeance, chronic and sustained migration, uneven economic development and inequality, sudden economic downturn, corruption, criminalization of the state, deterioration of public services, arbitrary use of state violence and human rights violations, the relative autonomy of the security forces, factionalism among state elites, and finally, external intervention by other states or parastate forces.

Christian Parenti puts this in focus with what he calls the catastrophic convergence of poverty, violence and climate change with the poverty being exacerbated by neoliberal policies and the violence being fed by arms provided various groups during the Cold War.

China, Europe the US and Japan still have functioning societies but I think we can recognize certain tendencies toward failed states. To keep social cohesion they need to focus on the social bond. I think they need a lot of very smart investment to deal with the catastrophic convergence we are facing but they need deleveraging from asset appreciation and a focus on basic social needs.

Whatever problems Japan has they seem to have a very high degree of social cohesion. Much more than the US in comparison.

Why is China finding it hard to fight the markets? Because there are no markets.

LMAO – Thanks

.

.

It is really much much simpler then all of that.

When the money was spent on required capital projects,

bridges, tunnels, sewer, water, a nation wide highway system.

The money provides a benefit for years to come.

Generations benefit from the NYC subway system, NYC sewer system,

and the Hoover Dam.

It is the same in the US, EU, China, Japan.

Initially as they grew, all economies benefited from such spending. China included.

When the money now, is instead spent on projects that will be infrequently

used, or possibly never used. That money is now wasted. Ghost Cities in

China the example.

And worse a) environmental destruction comes from the Ghost Cities

b) additional monies will be required to maintain the Ghost Cities,

and in the future c) additional monies will be wasted on removing said

useless cities, or they shall sit and rot on the land and keep it from being

utilized in any practical way.

.

.

What occurred was diminishing marginal returns. The early money

found use, in projects that provided a return.

The later money, found its way to useless projects with no or limited return

and probably in most cases like the Ghost Cities a negative return.

So it really is that simple.

Excess and diminishing marginal returns means QE today is going toward

projects with limited or no return, and in some cases a negative return.

.

.

Of course, unlike the US and other advanced economies, China lacks the checks and balances inherent in liberal democracies.

China does have systems of checks and balances of its own, (academics, workers, and party systems), and it also now has a high speed train network the USA can only wish for in a pipe dream.

It is not a 2-party system, but it is very much socially minded in all policy-making, at least nominally.

In other words, it is a socialist state with social accountability unseen in the so-called “liberal democracies.”

One thing in common with the LDs however is failure to live up to its own ideals.

Capitalism in China doing exactly what it says on the tin. Transferring asset ownership from the hapless masses to the most credit worthy and best informed citizens (aka the economic elites).

Credit expansion/contraction and other asset bubbling activities are just part of the game to seperate elite sheep from elite goats.

Credit switch on – houses/shares/whatever – up.

Credit switch off – houses/shares/whatever – down.

Every twist and turn of the roller coaster the weakest wannabe elites get thrown off, sharper turn the better.

Meanwhile farmers try to get crops grown, workers try to make widgets, train drivers try to drive and children try to play while the capitalist elites and wannabe assholes play with our wellbeing.

What does this analysis say about the transparency of China financial markets?