As readers may know, how much public pension funds are paying in fees, particularly for pricey “alternative” investment strategies like private equity and hedge funds, has become a hot topic. For instance, David Sirota and other reporters at the International Business Times have been digging relentlessly into which firms get lucrative public pension fund mandates, and whether people connected to those firms have been or become donors to elected officials. And investing in high-fee investments can’t be defended on its merits. The Maryland Policy Institute published a study that updated and reconfirmed the findings of an analysis performed two year earlier, that public pension funds that invest in high fee strategies like private equity give up billions in performance as a result.

As Dennak Murphy of American Federation of Teachers pointed out at a recent CalSTRS board meeting, “What is not measured is not managed.” The overwhelming majority of public pension funds don’t even try to track all the fees they pay. And worse, this willful blindness means those fees are not being properly negotiated either. Thus, choosing to be ignorant about total fees and costs gives the purveyors of complex strategies license to price-gouge.

Stung by the outcry over CalPERS’ admission that it did not keep tabs on one of the biggest fees it pays, the private equity profit share widely mislabeled as a “carry fee,” more public pension funds are trying to pretend that they capture their investment fees and costs. The problem is that these claims don’t stand up to serious scrutiny.

Yesterday, for instance, the New York City controller Scott Stringer tried passing off the line that the New York City pension system had taken a big step forward and now was tracking its total fees. Not only is that untrue, but the disclosures made by New York City of its fees and costs continues to be poor compared to that of other pension systems.

Pensions & Investments reported yesterday that the New York City Retirement System reported that it paid $709 million in fees to investment managers in its last fiscal year, and was trying to give the impression that as a result of a big push for more disclosure, it was now reporting all the fees it is paying.

Yet if you read the article with a modicum of attentiveness, you can see that that is false. In reality, Stringer is trying to have it both ways: to appear to be on the right side of a controversy, while not doing anything to ruffle the pension systems’ fund managers, many of whom are very influential political donors.

Here are the key parts of the article:

The figure represented a 33.7% increase over the $530.2 million in fees reported for the fiscal year ended June 30, 2014. However, the most recent fiscal year’s accounting includes many incentive fees that hadn’t been identified in previous annual reports…

City officials said they believe the latest information covers most of the investment management fees, adding that the new rules for fee transparency will provide an even more accurate picture.

The big tell here is the use of the “believe” language. When CalPERS requested carry fee data from all the funds in the entire history of its program, it was able to tell the Financial Times a mere ten days into the exercise exactly how many funds had not yet coughed up the data: a mere six our of over 850 funds over the life of the program. The fact that New York City is so fuzzy on what it does and does not have 22 months into the effort is a strong tell that they are not going about the effort in a serious, rigorous manner. The end of the article confirms this impression:

In its October letter to private equity and hedge fund managers, city officials asked for fees based on asset class and type, such as commingled fund or separate account. The fee information will be posted on the comptroller’s website.

The letter also asked that each manager prepare a one-time analysis to each pension fund of base fees, performance fees and other fees charged by each investment option. The letter asked that this information be provided by year-end, adding that future information about fees must be provided quarterly.

By contrast, South Carolina, which has set the standard for fee information gathering, has a detailed template that it has managers fill out, and then staff follows up with funds that have not completed it or claim they have difficulty completing it, to get the missing items.

Stringer appears to be reacting to a set of articles in the New York Post last month that criticized his transparency head-fakery. The first Post article, dated October 8, pointed out an embarrassing omission: Stringer had tried showing how much the city’s pensions were paying to money managers. He reported a total of $399 million in fees for a total pension system of $169.2 billion in assets.

The wee problem was that Stringer completely left out the heftiest fees paid, those to private equity funds and hedge funds. The Post had previously reported that the total fees paid were actually $530.2 million. So Stringer made a flagrant misrepresentation a month ago. And in his report to Pensions & Investing yesterday, he confirmed that the Post’s figures of the costs the year before were correct.

The second Post article, on October 11, pointed out that the accounting that Stringer had just issued contained some howlers, and also, despite the braying about greater transparency, took a step back on disclosure in key areas:

For instance, the firefighters fund said it paid just 0.59 percent in fees as a percentage of hedge-fund assets — less than what it paid managers to invest in small-cap stocks. Hedge funds typically charge investors a management fee of 1 to 2 percent of assets and about 20 percent of any gains each year…

Problem is, the city’s percentage rate is just a guesstimate. By his own admission, Stinger doesn’t know all the fees the city is forking over to hedge funds, private-equity firms and other outside managers. Nowhere in his report, however, is there a footnote explaining this.

What’s more, Stringer has taken a step back in other areas. He didn’t provide names of outside money managers in his latest report — something the pensions had divulged in previous reports.

If you look at New York City’s Comprehensive Annual Financial Report, the pension fund performance disclosure is remarkably thin (see pages xxi to xxiv). As North Carolina’ former chief investment officer Andrew Silton said by e-mail, “If this is what transparency looks like when someone is trying to be transparent, NYC isn’t revealing much.”

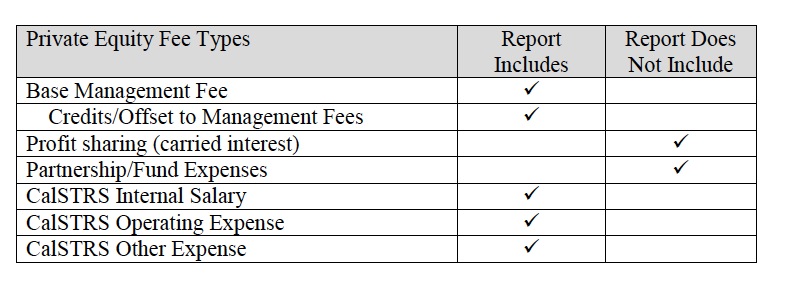

CalSTRS, to its credit, is at least not putting its foot in mouth and chewing in public as New York City has. Its annual investment cost report, dated November 4, at least show some data items are missing. However, even there, staff is misleading the board and the public as to what it is getting in the fee categories in private equity.

If you read the text, you’ll see that in fact the management fees are not reported fully. CalSTRS is using the same misguided approach as CalPERS, which is not surprising, since the current head of private equity at CalPERS, Réal Desrochers, ran the program at CalSTRS for many years before briefly retiring and then coming out of retirement to go to CalPERS.

As regular readers may recall, when private equity limited partners became upset about the level of fees that the general partners were taking from portfolio companies, rather than tell the general partners to cut it out entirely or put strict limits on it, the limited partners instead agreed to the peculiar device of having those charges offset in part against the management fees that the limited partners pay every year. Mind you, that does not make the management fees go away. It instead has the effect of having the limited partners pay a smaller amount in hard dollars and having the rest shifted onto the portfolio companies. But if you read the narrative accompanying the chart, you can see it argues that since the management fee is net of offsets, that has somehow been included properly.

This investment cost report also fails to include management fee waivers. It contains this stunning misrepresentation:

Management fees resulting from our limited partnership private equity investments generally reflect expenses to cover professional and staff salaries, rent, overhead, and other operating expenses of a fund.

We debunked this notion long form in an August post, Senior Private Equity Officers at CalPERS Do Not Understand How They Guarantee That Private Equity General Partners Get Rich. The bottom line:

One former private equity partner laughed at the notion that industry members were only getting by from management fees and needed to work hard to get rich: “The LPs [limited partners] lost that battle long ago.” He said that the heads of some firms make close to $100 million annually before “carry fees,” including firms that manage funds in which CalPERS holds investments.

So while major pension funds like New York City and CalSTRS are clearly feeling the need to appear to do a better job of fee and cost reporting, they are not anywhere near as far along as they’d like the public to believe they are. At best, to invoke a saying I heard in Caracas, “They have changed their minds, but they have not changed their hearts.”

Some disclosure is better than no disclosure, but what they should be showing is fees relative to returns.

You might also consider what portfolio effects accrue from the exposure to private assets vs public – which is harder to ascertain at the individual asset level.

As I think yves points out, some disclosure is an attempt at obfuscation, and by that obfuscation probably, in my laymans view, are trying to hide the “fees relative to returns”… ISTM that the game is take fees out secretly then later arrange reports to pension committees with numbers that sound fair with a bunch of CYA about how “we can’t be sure, it’s all in flux, so complicated…” correct me if I’m wrong please

In reality, Stringer is trying to have it both ways: to appear to be on the right side of a controversy, while not doing anything to ruffle the pension systems’ fund managers, many of whom are very influential political donors.

Stringer (and other pension fund managers investing in PE) may hope that the spotlight on PE price-gouging will be a 1 or 2 day story, then attention will move on to the next thing, so a little PR is all that’s required of him.

Thanks for keeping the spotlight shining on PE.

And any politicians receiving plush contributions from PE general managers are probably hoping the spotlight moves on to other stories soon.

This stuff is so awesome. I’ve got a recommendation for new SEC chair…

@Eric Patton – IIRC, you are not the first to recommend Yves for that position.

And, she would be awesome!

Of course, that could seriously compromise Naked Capitalism. I actually think Yves might be more influential running this site than if she became a part of the bureaucracy, even at the top. A political appointee is limited by the position they fill. At NC, Yves has no restrictions as to which issues she focuses on.

What financial qualifications does Stringer possess to qualify him for his position???

None whatsoever. But, like, a lot of cool kids supported him, and that always helps.

http://nymag.com/daily/intelligencer/2013/07/lena-dunham-endorses-stringer-quinn-on-twitter.html

i’ve already sent this piece to all my new york city employee friends. and they’re sending it on.

i supported spitzer but i thought stringer was a good guy. but in new york being a good guy means standing up to the money interests. it’s obvious that he isn’t.