Yves here. I’ve gotten similar arguments from many Europeans: that when you adjust nominally higher American incomes for how much we spend from our own pockets on healthcare plus the longer hours we work, we aren’t better off. And if you attribute a cost to stress (which you can also see in the level of prescriptions of psychoactive drugs here), it’s not hard to push this thesis further.

By Steve Roth. Originally published at Angry Bear

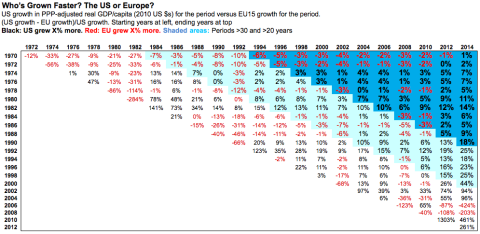

’ve pointed out multiple times that despite Europe’s big, supposedly growth-strangling governments, Europe and the U.S. have grown at the same rate over the last 45 years. Here’s the latest data from the OECD, through 2014 (click for larger):

And here’s the spreadsheet. Have your way with it. More discussion and explanation in a previous post.

You can cherry-pick brief periods along the bottom diagonal to support any argument you like. But between 1970 and 2014, U.S. real GDP per capita grew 117%. The EU15 grew 115%. (Rounding explains the 1% difference shown above.) Statistically, we call that “the same.”

Which brought me back to a question that’s been nagging me for years: why hasn’t Europe caught up? Basic growth theory tells us it should (convergence, Solow, all that). And it did, very impressively, in the thirty years after World War II (interestingly, this during a period when the world lay in tatters, and the U.S. utterly dominated global manufacturing, trade, and commerce).

But then in the mid 70s Europe stopped catching up. U.S. GDP per capita today (2014) is $50,620. For Europe it’s $38,870 — only 77% of the U.S. figure, roughly what it’s been since the 70s. What’s with that?

Small-government advocates will suggest that the big European governments built after World War II are the culprit; they finally started to bite in the 70s. But then, again: why has Europe grown just as fast as the U.S. since the 70s? It’s a conundrum.

I’m thinking the small-government types might be right: it’s about government. But they’ve got the wrong explanation.

Think about how GDP is measured. Private-sector output is estimated by spending on final goods and services in the market. But that doesn’t work for government goods, because they aren’t sold in the market. So they’re estimated based on the cost of producing and delivering them.

Small-government advocates frequently make this point about the measurement of government production. But they then jump immediately to a foregone conclusion: that the value of government goods are services are being overestimated by this method. (You can see Tyler Cowen doing it here.)

That makes no sense to me. What would private output look like if it was measured at the cost of production? Way lower. Is government really so inefficient that its production costs are higher than its output? It’s hard to say, but that seems wildly improbable, strikes me as a pure leap of faith, completely contrary to reasonable Bayesian priors about input versus output in production.

Imagine, rather, that the cost-of-production estimation method is underestimating the value of government goods — just as it would (wildly) underestimate private goods if they were measured that way. Now do the math: EU built out governments encompassing about 40% of GDP. The U.S. is about 25%. Think: America’s insanely expensive health care and higher education, much or most of it measured at market prices for GDP purposes, not cost of production as in Europe. Add in our extraordinary spending on financial services — spending which is far lower in Europe, with its more-comprehensive government pension and retirement programs. Feel free to add to the list.

All those European government services are measured at cost of production, while equivalent U.S. services are measured at (much higher) market cost. Is it any wonder that U.S. GDP looks higher?

I’d be delighted to hear from readers about any measures or studies that have managed to quantify this difficult conundrum. What’s the value or “utility” of government services, designated in dollars (or whatever)?

Update: I can’t believe I failed to mention what’s probably the primary cause of the US/EU differential: Europeans work less. A lot less. Like four or six weeks a year less. They’ve chosen free time with their families, time to do things they love with people they love, over square footage and cubic inches.

Got family values?

I can’t believe I forgot to mention it, because I’ve written about it at least half a dozen times.

If Europeans worked as many hours as Americans, their GDP figures would still be roughly 14% below the U.S. But mis-measurement of government output, plus several other GDP-measurement discrepancies across countries, could easily explain that.

There is more inequality in The US.

The top 1% are taking a much bigger slice of the pie.

If you compare the income of the 99% the gap will be closed a few percentage points.

Yes, and likewise, subtracting out financial services and banking on both sides of the equation might also even things out.

For example, this recent visualcapitalist.com USA GDP x region map shows the domestic disparity weighting most heavily to NYC and DC nexus areas, the areas housing so much of heavily-subsidized finance and MIC sectors.

This contemplation leads to an interesting hypothesis: That if adjusted for MIC and TBTF GDP sectors and suppression of labor rights on the USA side, we might find that Americans have much lower GDP than Europe, even though they are working much more and paying more medical, private transport, stress meds from social insecurity, etc. than European counterparts.

Ya know, SCREW the referent to “GDP” on “GNP” as any kind of measure, since those sorts of referents, beloved of Economists ™, do not measure and indeed positively crush and obscure what honest decent people would consider their real wealth. Average, median, outlier, too bad there’s not a mathematics of decency, comity, sustainability that could be taught to people, to arm them against shit like ChicagoMisesFriedmaniac Idiocy…

Thanks for the good laugh.

Indeed, wildly wasteful and overpriced goods and services like healthcare and college in the US ‘look good in GDP terms’ but have little – or in many cases negative – correlation to health & welfare of the citizenry. USians who work crazy hours and blow any excess income on spending double per capita for healthcare which is no better or worse than in your average European country thus have an overall lower quality of life, but ‘ooh, look at our incomes and GDP!’

Turns out neoliberalism and Gemütlichkeit are fundamentally incompatible – whodathunkit?

+ Many

As an “European” i have sometimes wondered if the reason USA seems to have such a problem with crime, has to do with social security, or lack of such. This then lead to people reaching for desperate means to keep going one more day. This because i have observed that the people doing various crimes over here are likely to have some kind of addiction. There is little crime towards covering basic needs, because they are provided for via various social security systems.

Thank you!

You are correct digi_owl. The very low level and poor quality of the safety net we do have in the US does indeed contribute to the amount of property crimes such as theft and burglary. I believe it also has a significant effect on crimes against others. When someone is frustrated and angry because they cannot find work that pays enough to support their family, they are much more likely to strike out at any perceived slight.

Add fundamentalist religion to that list. IMO economic despair and fundamentalism are effectively the same thing, and not just in the US.

Its an interesting point, one I’ve often wondered about, but I don’t have the basic knowledge of GDP accounting to say if it really makes a difference. But as one obvious example, since the US spends something like 17% of GDP on healthcare, while in Europe it averages around 10%, yet by almost all measures is better, then there is a huge ‘missing’ lump of GDP which does not relate to better (or richer) quality of life.

I think it is difficult to compare real standards of living – you can be earning a lot of money, but living somewhere like Manhattan or London, and so feel you are always struggling to pay the rent, with the opposite in other contexts. As one example, there if you have a basic government job somewhere in Northern Ireland you can feel quite rich as living costs are quite low – presumably the same applies to somewhere like Montana.

I’ve had this discussion quite a lot with American friends – comparing what we earn, compared to what we have to spend in order to have free cash. Obviously, Americans pay lower tax than us Europeans, but pay far more in insurance and retirement saving – if these are calculated in a different way as this article suggests, then there could be a very significant discrepancy, especially if the true high ‘costs’ of private provision are not fully accounted for.

It all boils down to what is measured in GDP. For example Cuba had a pitifully low GDP, because there is little property ownership and no housing market, healthcare and schooling is all free. Their standard of living is several times higher than GDP per capita suggests.

High land prices inflate GDP, not the buildings on the land just the land value itself. The USA has a lot of land which is transacted a lot, these transaction adding almost nothing to the value of life. Could be the US just transacts more stuff with little social value like IP and land.

Likewise I’m of the opinion the British do more DIY, housework and gardening than Americans. This is all unpaid work and not reflected in GDP. I suspect Americans buy more DIY gadgets to achieve the same end effect.

Another thing British wipe up in the kitchen with cloths, Americans use disposable paper for every single thing. This must be about 5% of GDP.

The distances in such a big country needs more gas and energy, there’s another few percent GDP. More pitiful public transport = more cars + a few percent.

It all adds up.

http://www.bloombergview.com/articles/2015-11-06/inequality-and-excessive-debt-cause-financial-crisis

For 50 years, private-sector leverage — credit divided by GDP — grew rapidly in all advanced economies. Between 1950 and 2006, it more than tripled. Was this credit growth necessary?

Leverage increased because credit grew faster than nominal GDP. In the two decades before 2008, credit in most advanced economies grew about 10 percent to 15 percent a year, versus 5 percent GDP growth. At the time, it seemed that such credit growth was required to ensure adequate economic growth.

If central banks increased interest rates to slow the credit growth, standard economic theory said lower real growth would result. The same pattern and the same policy assumptions can now be seen in many emerging economies, including China: Each year, credit grows faster than GDP so that leverage rises and credit growth drives economies forward.

===============================================

There used to be a commenter (he was religious too but I forget his moniker) who always went on about land value and land tax. I wish I had paid more attention to him now…

Anyway, when I was a kid, and you bought a house, it seemed to me the vast majority of the value was the HOUSE – the cost of the lot wasn’t that significant.

I remember when there was the housing bubble, and I got my insurance adjusted, that the majority of my “property” value was the land, not the house – which really surprised me.

So if you keep making the land more, and more expensive, rising in price faster than incomes, GDP, or productivity, it seems to me that eventually you get poorer.

So are rising land prices really a reflection of the “market” or is it just a reflection of ever more debt created to buy ever rising land prices?

And of course, it makes it seem like we have so much more stuff, when in fact we have just more overpriced stuff…

Flips and rents — Opportunity! In the land of the free and home of the homeless.

Correct me if I’m wrong, but when you have several parties involved in the healthcare payment system, doesn’t each transaction count as production in the GDP calculations. Things like that can cause the same service to be counted several times in GDP, compared to it being paid by the government.

Maybe, in the UK you go to hospital get treated and go home. The hospital buys the drugs and pays the doctor. If the hospital has a Government account there would be no payment from Government to hospital. I don’t know how hospital accounting and payment systems work though.

In the US you pay insurance then the insurers pay the hospital, the hospital buys the drugs and pays the doctor. All are counted as transactions for the same service. The insurance market being completely wasteful extra administration function.

A big subject, but briefly, in a single-payer system such as the UK’s National Health Service (and I’ve never entirely been happy with that being described as ‘single payer’; technically of course it is but that terminology suggests it is like an insurance policy but in fact it is nothing at all like an insurance policy as far as an end user is concerned) then the only significant accounting consideration is what is Capitalised expenditure and what is Revenue expenditure.

So if money from the treasury is allocated and then that money is spent on something which becomes an asset (an MRI scanner, a hospital building, a toilet seat or whatever) then that up-front cost can be spread over the economic life of the asset. Thus reduces the initial hit to government expenditure. But for things like staff costs, drugs, consumables — anything that has no long term residual value — that has to come straight out of government spending.

But what if the government is running a deficit? Surely then it is academic — it’s all just “borrowed” money anyway? Here some (and I think they are very misguided) economist types try to split the expenditure back into that which is for “long term” assets (where the government borrowing is supposed to then magically become okay) and “short term” (which, apparently, you should not borrow for because when interest is added that pack of bandages ends up costing many times its initial outlay). MMT types will take issue with this artificial splitting.

Once you introduce insurance into health funding, things become way, way more complicated. Insurance company accounting is extremely complex (again, being brief but missing out on a lot of information in the process) because insurance companies receive the policy premiums up-front, but only lay out the costs of honouring the policy’s coverage later — or even never — they sit on a “float”. This is a pot of money which the insurance company can earn a return on. But then something can go wrong with the investment strategy for the float and the insurance company has to eat losses. All of this insurance accounting shenanigans is effectively an additional layer of gloop sitting on top of the “business” of actually buying the healthcare services from the healthcare provider when the policy holder makes a claim. Even this gets complicated because, naturally, the insurance company will never pay the “rack rate” i.e. what I would have to pay “retail” if I walked into a hospital uninsured and wanted to cover my healthcare costs on a pay-as-you-go basis.

Looking askance (and appalled) at the US system of health insurance and healthcare, I don’t think I could ever hope to come up with anything more convoluted and costly.

Actually, Clive, I believe that in the UK, physicians and other medical personnel are employed by the National Health Service–is that not the case? In the US, I have heard that consistently referred to as a system of socialized medicine.

In the US, the example of a single payer system most often cited is the Canadian one:

“Single-payer national health insurance, also known as “Medicare for all,” is a system in which a single public or quasi-public agency organizes health care financing, but the delivery of care remains largely in private hands.” — Physicians for a National Health Program

Undoubtedly, this distinction is made because of the American horror of anything with a whiff of “socialism.”

There’s no single answer to “who employs the healthcare professionals” in the UK’s NHS. Primary Care (“General Practice” or “GPs”) are self-employees or, more commonly, in a partnership. Under the attempted neoliberal takeover of the NHS, they become “fund holders” which means they get given a budget by the NHS and then pay themselves — and the costs for providing primary care — out of that. The existing GPs don’t attempt to make a “profit” — their salaries are set by the NHS.

The reason for this move to a “fund holding” arrangement is to let private contractors tender for the rights to provide primary care in a geographical location. Which, of course, is an attempt to enable private sector looting of the NHS. Luckily, the political risks (messing about with the NHS is a hot-button issue of the highest order here) means relatively few takers have come forward — so far. But many, myself included, fear for the future because, as you so rightly say Carla, we can’t have socialist ideas being successful now, can we?

For hospital-based specialists — oncologists, ophthalmologists, anaesthetists and so on, these are employed by the hospital they practice in. The hospitals get their funding for the department of health (i.e. the government department who allocates the NHS budget).

As the department of health doesn’t get its money from a single source of funds (it just takes a cut of overall government spending) I think this is the key difference between the UK and Canadian systems — the Canadian funding is from a dedicated source (“hypothecated”) but I might wrong here.

A single payer has a monopsony, and has enormous bargaining power compared to the disjointed network of skimmers that the US subsidizes.

For the most part that is wrong, because gdp only counts value add. Its more complicated in services, but in terms of goods, say walmart buys a pair of shoes for $20 and sells for the $30, only the additional $10 gets counted in gdp by definition. Now calculating all these examples across a $18 trillion economy is complex and that is what govt. agencies have pretty sophisticated methods to do. Still doesn’t mean that there isn’t waste in US healthcare, but this is roughly how GDP is calculated

@tony – Insurance premiums are included in the GDP figures as a proxy for the amount of services paid for by the insurance companies, due to the difficulty of measuring related to the complexity of the discounts and pricing practices of the insurance companies.

@matt – For the sale of real goods, only the final prices paid by the consumer are included in the GDP figure.

I realise in my comment I strayed from the direct point in the article – it would be good to know if someone has actually tried to quantify the difference between a publicly delivered service and a private one.

GDP is a construct invented by economists and used by politicians to pull the wool over the eyes of the rabble. It has little to do with health, wealth, or societal well being.

If you look at individual median net worth as a measure of wealth and security the USA looks more like the third world economy it is rapidly becoming.

2013 Wikipedia “List of countries by Wealth”

(https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_countries_by_wealth_per_adult)

USA $ 44,911

Australia $219,505

Italy $138,653

France $148,350

We’re just kidding ourselves that we can construe a national capitalist health care system based on limited competition between private insurers and providers and maintain both costs and services. It’s killing us all in more ways than one. Somehow the big corporations have bought into this idea, not just the big health insurers and big pharma. The general public, meanwhile, is almost tapped out, nickel-and-dimed to death. What a witches brew. It makes no sense that corporations think this is good business. They are not doing well; they are stiffing all their pensioners because they can’t make sufficient earnings, handing over their companies to corporate raiders, and etc. And now they all want to dismantle Social Security. That really should be a howling wake up call. Single payer, well managed national health care is a benefit to corporations probably more than citizens. As would be nationalized pension funds, nationalized higher education funding and probably some amount of nationalized housing. Instead we have cannibal capitalism and the corporations trip over themselves to offshore their failing enterprises. Who wouldn’t?

The yearly report of OECD on health is just out, by the way, and it always makes for interesting reading:

http://www.oecd.org/els/health-systems/health-at-a-glance-19991312.htm

Thanks for that

Ironically, in the report summary, it is noted that life expectancy is rising in most countries.

Of course, just this last week we had those people who dis-aggregate data and found out that life expectancy isn’t going up for middle aged white people in the US…

Yes, of course. As usual, you can only find what you look for :-)

If you want to determine who’s richer, you need to also acknowledge the value of time, something the author did by mentioning vacation time. But focusing only on how less working time affects GDP isn’t enough – having more time off is a form of “riches” which goes beyond monetary measurement: more time w/family & friends, more time for relaxing, hobbies, travel, wellness, etc. which can lead to more life satisfaction – and better health.

A better assessment of who’s “richer” would focus on both money AND time. True, this would be more complicated, but my guess is, it would be much more informative.

I grew up & lived in LA/so. CA for 29 years, then moved to Berlin (Germany) 19 years ago. It’s very difficult to make quantifiable comparisons of the 2 cities: e.g. in LA, a car is an absolute necessity, whereas in Berlin it would be a luxury (I don’t own a car). In order for “richness” to be measured meaningfully, quality-of-life differences (such as “time spent sitting in traffic, seething” vs. “time spent reading in the subway”) must be somehow addressed.

These differences also include health care: here in Berlin, my public health insurance covers everything. Recently, a good friend in LA had to save up $4000 for a colonoscopy which wasn’t covered by his (very expensive) health insurance. How does this situation affect GDP – and “richness”?

For what it’s worth, although I make less money here than I did in LA, I feel much richer – not only in terms of time, but also money, as I no longer have to spend so much on a car and health insurance. It seems a true measure of richness would accurately measure the impact of much more than just GDP.

I have a similar history, having moved from Southern California to Scandinavia more than 5 years ago.

My Gross and Take-Home pay are probably half of what I made in the US, but my life is much better. In addition to having abandoned the car and health insurance premiums, not paying the absurd rentier prices for lousy internet and phone service saves a bundle. I’m healthier than I ever was in the US (haven’t actually been to see a doctor since emigrating) and have used the shorter work-weeks and longer vacations to pursue a number of new and fulfilling hobbies and life experiences.

Unfortunately a similar quasi-religious focus on GDP seems to be commonplace in politics here, but at least there are voices in the public debate that question the wisdom of doing so.

I definitely agree with you in the very valid point you make about what is, in effect, compulsory expenditure in the U.S. — buying and running a car being a good example of this. If in the place you live, life becomes bordering on impossible without a car, then a car is a necessity and not an optionally purchased consumer good.

I wouldn’t have dreamed of owning a private car in urban (the vast majority) areas while living in Japan. Even in southeastern England you can manage without one with a little effort. I reckon that saves me a minimum of three to five thousand pounds a year. Which, getting back to the original article, the avoidance of spending does nothing for GDP.

http://www.forbes.com/sites/timworstall/2014/08/25/britain-is-poorer-than-any-us-state-yes-even-mississippi/

There is actually quite a few articles that assert that Europe or any particular European country is poorer than Mississippi.

Now, I have been in England (and Wales) a number of times (work as well as tourism and for a period over decades now), and due to…various proclivities, I am not always just in the tourist neighborhoods – I think I have a pretty good overview. And, I have also been in Mississippi (I would also say not just the tourist neighborhoods….but there really aren’t any).

And as much as I believe in documented data and not anecdote, I simply do not believe that England is poorer than Mississippi in any meaningful sense. It is certainly a good example of how numbers are crunched. Or as my friend always says, “Figures lie and liars figure”

Three thoughts in relation to your comment:

First, we MissiUSsippians would dearly love to be as “poor” as the U.K. Especially in terms of health care.

Second, the invidious comparison might ring true if one were to compare Mississippi today to England in the days of Charles Dickens.

Third, there are no tourist neigbhourhoods, true. Mississippi is Neoliberalism in the raw.

Welcome to the Neo New World Order, as Mr. Haygood says, comrade.

I believe government spending on weapons for the military is another item included in GDP. Another huge number to cheer and be proud of, right?

Spukhafte Fernwirkung, Tom. See simultaneous post below.

Then there’s military spending. Of course one must not underestimate how the experience of crushing small countries boosts the testosterone levels of Americans and how this contributes to their perceived quality of life.

‘Is government really so inefficient that its production costs are higher than its output?’

In the former Soviet Union, examples of value subtraction were well documented. Where comparisons are possible (e.g., public vs parochial K-12 schooling in the US), the public sector appears to spend about twice as much for the same output, even after correcting for mandates such as IDEA (Individuals with Disabilities Education Act).

The central fallacy of Roth’s thesis is that market cost is “much higher” than production cost. On the contrary, a reasonable rough assumption is that the efficiencies imposed by market discipline (e.g., lean staffing; less generous pensions and benefits; tighter linkage of pay to performance) roughly offset the profit margin that’s absent from public goods.

America’s defense subsidy of Europe via NATO — quite aside from the likelihood that it’s a prominent example of value subtraction — can explain Europe’s ability to track U.S. growth despite its smaller private sector.

Advertising is a huge cost that exists in the.private sector economy that doesn’t exist.in the government sector.

It is Pharma biggest cost,.running neck and neck with R&D.

Let’s be fair. Our own market-based health care system has achieved USSR-style levels of value subtraction. We are exceptional in that.

It will be interesting to see what North America looks like in 40 years after the boomer bulge has gone through the system. Millions of retirees stuck in their houses and not enough money to maintain them properly.

I keep on getting an image of Atlantic City or Detroit repeated across North America. In the meantime, I see Europe looking more or less the same because their infra was built to last centuries.

There’s also the U.S. system of taxation, which tends to suck up money at every level. I think that the animus of many Americans toward being taxed is that they are taxed everywhere and constantly. (And, yes, I’m aware of the big VAT taxes hidden in prices in Europe.) But someone in the U.S. pays federal income taxes, FICA, health insurance (let’s call it a tax), and excise taxes to the feds on utilities. Then at the state level, there are sales taxes, excise taxes, and income taxes. At the local level, there are property taxes and excise and sales taxes. Even at the basic level of the monthly phone bill, an American is reminded of being taxed. And if you add it all up, you end up with a total that is at “European” levels or even higher.

The more I think about GDP, the more useless it seems as a measure.

For example, in the U.S., when sales of soft drinks, fast foods and and other similar items increases, that goes in the plus column for GDP. Is there also an increase in prescriptions and treatments for diabetes and high cholesterol that go along with it? Put that in the plus column as well.

Is Monsanto having a banner year with Roundup sales? Well done, I say, let’s add that to the GDP total. Wait a minute, at the same time there also seems to be an increase in cancer screening, diagnoses and treatment? That’s all expensive stuff, in addition to causing untold pain, misery and death. But at least we can add all that revenue to GDP to make us all feel a bit better, right. At least the ones of us still alive.

In short, GDP is not only useless, it’s delusional, as a measure when used in isolation, isn’t it?

Gross Domestic Pollution.

Steve supplied an answer to a question I worried over because I have been trying to make the point that greater American inequality of pay should lead to less efficiency via too much income to spend at the top leading to what I think is called secular stagnation — and — lower productivity at the bottom of the workforce via worse education and healthcare, etc., etc. So why do we have higher per capita output I couldn’t explain.

“All those European government services are measured at cost of production, while equivalent U.S. services are measured at (much higher) market cost. Is it any wonder that U.S. GDP looks higher?”

Steve’s answer is all important to me because I am trying to the picture of an economy is sort of a perpetual motion machine and that inputs always become outputs and vice-versa in order to do away with the worry that higher consumer prices caused by collectively bargaining labor will cost jobs.

* * * * *

To wit [cut-and-paste]:

In a high union density (or a high co-op, that is employee owned) market consumers will pay more for less goods from firm “A” — causing some of firm “A”employees to lose jobs; and because consumers who continued to patronize firm “A” in spite of higher prices now have less money to spend over at firm “B”, some employees will be laid of fat firm “B” also. If the employees of “A” now hide their new pay raises under their mattresses that will be the end of the economic effects.

But I’m guessing that the employees of firm “A” will have a propensity to spend their new incomes at firms “X”, “Y” and “Z” and don’t forget “B” and don’t forget even “A” — making jobs for the formerly laid off employees of “A” and “B.”

This perpetual motion machine ran on auto-pilot during the “Great Compression” (as long as you were white) — even under a five-star general, Republican president who didn’t know that much about this country having spent most of his life outside of it and note to quick to worry about segregation. The perpetual motion mechanism: high union density.

Of course if too much (way too much!) income leaks off to the top 1% who can’t spend it fast as they get it the motion slows down. I think this is called secular stagnation.

And if too little income reaches the bottom the productivity of a huge (and growing) segment of the workforce (or would-have-been) workforce drops way off due to lower education and even lower nutrition and more generally dysfunctional society (e.g., 100,000 Chicago gang members).

[snip]

Must not forget that of course Europeans work shorter hours for higher pay than Americans — forcing our labor to work more to achieve the same standard of living and leaving our “surplus” to be picked over by ownership. I think that a few years or more back we worked 50% more hours than Germans though that gap may have closed up some now.

How meaningful a measurement is GDP for the citizen of the country?

Once upon a time the metric of a country (somehow related to the citizen?) was about amount of steel produced in the country, that metric was abandoned. Maybe it is time to replace the GDP metric as well with something more relevant for citizens? & no I don’t know what that metric might be :-)

Most people who talk about GDP growth being necessary are the direct beneficiaries of the supposed/expected GDP growth of their proposed GDP growth-enhancing policy…. The proponents of the policy got their benefits and as a side-effect there might have been some GDP-growth. Cui bono?

Striving for GDP-growth can be (but isn’t always) about as honest as gaming (abusing the inevitable flaws of) the system for personal gain. Anyone remember how rising house-prices was seen as a good indicator of a wealthier population? Now we know otherwise or?

All measurements can be gamed, the measurement of GDP is currently gamed a lot.

Well the opposite of GDP growth would be a negative GDP. And that’s just something that isn’t attractive to consider (like the 1930s Grapes of Wrath and such).

As examples, please see Detroit, et al, for communities that experienced absolute flight of human capital, and intellectual capital.

Historical discussion of the issue, both from ~ half a century ago:

Robert F. Kennedy challenges Gross Domestic Product

Kenneth Boulding: The Economics of the Coming Spaceship Earth

Thank you for adding this link, erichwwk. I had just been about to excerpt the same passage from Kennedy’s speech in Kansas in 1968, when I became immersed in the beauty of the entire speech of which this passage is a part. All of the speech is worth revisiting:

http://www.jfklibrary.org/Research/Research-Aids/Ready-Reference/RFK-Speeches/Remarks-of-Robert-F-Kennedy-at-the-University-of-Kansas-March-18-1968.aspx

I am mourning his loss all over again.

One of the truly great speeches of history.

Another way of looking at international comparisons is measures of social wellbeing or rather ‘evils’ such as juvenile crime, teenage pregnancy, relationship breakdown etc. The lasy set of data I saw for the ‘advanced world’ put the US at the bottom and the UK second bottom (i.e. highest levels of social evils).

Perhaps this is a better way of looking at welfare?

Sounds just right.

In the case of health services I have read many times that the private health in the US has a lot of administrative costs compared with public health systems in Europe. Economic GDP accounting sums those costs as a feature (more wealth), while you migth consider those an inefficiency of the health system (costly). So it just depends on the glasses you use. The “economic glasses” as miopic as they are should be used with caution.

How much of the European labor force are independent sharecrop… um, contractors?

…they’re working on it –just give em some time. And a hat-TTIP or three…

When I tell my European friends and colleagues how much we pay in health care (assuming we avoid the booby-traps of out-of-network costs), and education, and how little vacation we get, they are shocked, and they suddenly don’t feel that poor anymore…

But on the other hand, England, with the highest population density in Europe and very high immigration, is starting to get really poor – more and more elderly are dying of hypothermia each winter, and childhood nutritional deficiencies, that had been eliminated are starting come back. I recently read that if you use purchasing power parity, if England were to become the 51st state it would be the poorest in the union… Yes a lot of this is likely Neoliberal Thatcherism, but maybe not all…

So here’s another factor to consider: population density. Classical economics says that it is primarily the rate of increase of population that matters, not the absolute numbers. And yet, a high population density is a kind of tax on an industrial economy. If you can just pump fresh water from a stream, that’s easy. If you have to recycle it and conserve it and purify it etc., that’s a lot of extra cost and effort to get what is virtually free in a country with more resources. I suggest that as industrial economies grow, that initially population density is not a major factor, but as time goes on it ultimately does limit things. Industrial societies with abundant resources should tend to asymptote at a higher physical standard of living than societies with scarce resources per capita.

Excess winter deaths through hypothermia are also on an upward trend in the U.S. too http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm6151a6.htm

In countries which are sufficiently wealthy to be able to afford to pay for their primary energy needs, excess winter mortality is indicative of inequality not necessarily an impoverished country.

If you’d had stated that England is beset with rising inequality I’d definitely agree with your citing of the increase in winter mortality discrepancy. But it doesn’t convincingly prove declining average living standards. In England there is most certainly a problem of an underclass of 75+ year old people who cannot afford to heat their homes, but that doesn’t tell you anything about affluence, or any lack of it, in other age groups.

Also see this breakdown by age and sex:

http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm6406a2.htm

That upward drift in excess winter deaths for men aged under 65 is highly suggestive to me of the same underlying causation identified here.

Please explain the high quality of life in the Netherlands, a country of similar pop density to England.

The Netherlands have been rich for a long time – essentially as longas the country’s existed.

I believer their pop density is even higher than England’s, one of the highest in the world outside of city-states. Hence the massive land reclamation.

Good grief.

We’ve entertained any number of European visitors.

ALL flatly agreed // were totally overwhelmed by how much stuff Americans had — up and down the income scale…

And how large their homes were…

And how much space they had, personally … and how BIG America was.

None of these visitors were at all poor — by European or American standards. Millionaires, they were.

True, but tons of stuff and lots of space to keep it in, although impressive at first blush, do not equate to greater well-being.

There IS some psychic benefit to the lower US population density — at great environmental cost. As a retired US citizen who lived mostly in the SE US but also in Europe in three stretches totaling almost 20 years, I see a correlation between stress and physical crowding. However, I also believe that the greater access in Europe to free or low-cost public goods (health care, transportation, education, cultural opportunities …), more stable social and employment relationships, more personal time, and a universal understanding that we work to live, and not the other way around, are only some of the advantages that make folks “rich” in the broader sense over here.

US Americans’ space and stuff are visible, tangible, and dramatic to most folks from the other side of the Atlantic. The countervailing European advantages are mostly intangible, invisible, and hard to quantify per household. I rather doubt that, aside from upwardly-mobile professionals in the prime of their careers, most Europeans would choose the US lifestyle over their own after a fairly short time of actually living it.

Unfortunately, the EU has been hijacked (nay, controlled from the outset) by the same transnational neoliberal powers that have created US dystopia. I see a distinct narrowing of the European advantage now compared to my first sojurn three decades ago.

I remember watching a long-ish YouTube of reaction shots to the “Red Wedding” scene from Game of Thrones. Whether that provided a good random sampling of the interior of the typical interior of the American home I don’t know, but I recall being amazed at the sizes of the rooms, as well as the sheer quantity of kitsch and poorly constructed furniture. Some strange notion of comfort seems operative.

Oh, c’mon, that’s too easy, Lambert. How do we think income level corresponds to whether or not a household has premium cable channels?

And among a self-selected group of people, who’s going to feel more willing to record and upload a video of themselves in their living rooms? People with old, small, or modest homes, or people with costlier ones?

(The skew of the size of the rooms and amount of stuff is obvious, I mean. Kitsch is a whole ‘nother issue.)

“US Americans’ space and stuff are visible, tangible, and dramatic.” As I said. I’ve been in wealthy homes; these were not. I’ve been in homes more poor; the feel is the same.

“Kitsch” isn’t quite the word I want; it’s more like “imperial, with the decorative surface stripped off.” So there’s an emptiness and a bulk to it simultaneously. It’s very odd.

“I rather doubt that, aside from upwardly-mobile professionals in the prime of their careers, most Europeans would choose the US lifestyle over their own after a fairly short time of actually living it.”

I don’t know about “fairly short”. Granted, I come from a smallish, comparatively poor, European country, with a society extremely averse to risk (sometimes I think that all the daredevils emigrate, leaving behind those that think that it is better to have a bird in your hand than two birds flying). But the impression I have is that, for “upwardly-mobile professionals in the prime of their careers”, the US is indeed a bit of a promised land. What strikes positively European visitors to the US, in my experience, is not the sheer size of things or the amount of stuff (yes, they comment on that, but not necessarily in a positive way) is the feeling that everything is possible. That is the most common positive comment about the US that I hear, even from people that are wary of capitalism, the market economy, etc.

Thanks, Isabel. Your comments are invariably enlightening, and no exception here. I agree that for strongly career-oriented folks looking for opportunity, the US is still very attractive for the reasons you cite. Even post-GFC, the 80th (or maybe 90th) %ile and above are still living large on both sides of the Atlantic, and the daredevils in that cohort can surely gain by emigrating to the US, presuming that there aren’t already enough H1-B indentured servants to sate the demand for their particular skills or connections.

My remarks were oriented to the median family, working for a living, not for the stimulation, glory, power, high income, or whatever makes a top tier careerist tick. In my view, the western Europe of, say, 15 years ago, yielded a distinctly higher quality of life for that cohort than the US of A. These days, I think they’re still ahead, but not so much; despite the EU starting off with that handicap, it’s gaining on the US in the race to the bottom with surprising speed.

I have never been to the States, but my husband was from California and he lived in the Bay Area most of his life. He used to say that only later in life he realized that he grew up in the absolutely best years (post WWII) and that they wouldn’t last for ever. I can still see him shaking his head and saying “My people… my people..”…

But when he moved to Europe there were things he really appreciated there: safety, for one (it took him a while to lose the habit of never sitting with his back to the door in a restaurant…), healthcare (the price of drugs always surprised him) and, I think, a general feeling that people mattered. But there were other things he missed sorely: the “can do attitude”, the sense of community (I remember him looking at a French river full of garbage and saying “Why don’t people clean it?”, meaning the people that obvioulsy enjoyed it, not the commune!) and the service, as in “the customer is always right”!.

But when I mentioned the “everything is possible” thing, I wasn’t particularly thinking of professional people. Most tourists mention it. I guess it has to do with lack of regulations, a sense of personal freedom that is, apparently, strikes Europeans when they visit the US.

Oh, and thank you for your kind words, BillC (funny, my husband was also BillC!). I guess a different perspective is always enlightening :-)

Having more ‘stuff’ and bigger houses doesnt make us richer… If we have ‘stuff’ instead of healthcare or leisure time, we are probably poorer.

Oh yeah. And I forgot to mention that most Americans get lots of ‘stuff’ by loading up on debt, creating an illusion.

The US relies on the need to keep up with the Joneses, thus the need for more stuff, as well as the old he/she that dies with the most toys wins. When you consider that a lot of folks don’t take all the vacation they get in the US for fear of being seen as slackers,

What richer means is in the eye of the beholder more than anything else. Of course also what richer means has been the subject of a 2400+ year discussion in philosophy. (See Stoics, Epicureans, and other schools, as well as the various religious points of view.) In the US you have some churches preach the gospel of prosperity, which other sorts of Christians would say makes Christ weep.

You should watch Elizabeth Warren’s 2007 talk at Stanford. At that time, she reported that the median U.S. house, in the past 30 years up to 2004, had added a second bathroom, or a third bedroom, but not both. And the median square footage was fairly modest — around 1100 or 1200 sq feet, IIRC.

(All the new McMansions were new construction for wealthier people, and not representative of the median.)

Now, perhaps that still is big by European standards, but that’s partially a population density thing — NY apartments are tiny compared to suburban houses.

The U.S. is enormous, it’s true. And culturally, we like our personal space.

Granted, the US is less densely populated than Europe, land is therefore cheaper and houses can be larger for the same or less money. However, are the houses built to the same standards as in Europe? Not my impression from visiting family over there.

Also, as several people have pointed out, it is easier to live a car-free life in Europe, while almost impossible in the US.

And how much of the rest of the stuff is actually necessary and useful? Maybe you need all the kitchen gadgets because you work too much to take the time to cook – or you even go out instead and have no control over the quality of the food you put in your body.

There is a lot more to quality of life and health than mere numbers and just having more stuff does not mean you are better off.

You have to understand how the word “efficiency” is defined.

In economics, the word “efficiency” refers to PARETO EFFICIENCY and not technological or managerial efficiency as understood in the common parlance.

Goverment spending is NOT PARETO EFFICIENT. Pareto efficiency has absolutely nothing to do with technological or managerial effeciency.

Everyone realizes that GDP is a flawed way to measure the health of an economy. The U.S spends 30-50% more per capita on health car than do Europeans. But this expense makes our per capita GDP look better than our European friends even though they are living longer. Then there is also the higher costs that the US incurs for incarceration of a larger percentage of its people and the much higher defense expenditures. This adds a lot to GDP without adding much to overall societal well being.

I think we need new metrics. What interests me is the idea of asking the question, how many hours does someone have to work, at a nation’s median hourly wage, to be able to afford some defined standard of living? This target standard of living would take into account the basics such as the cost of housing (in a neighborhood with low crime rates), cost of food and clothing, cost of healthcare, cost of education etc. I would like to see someone do this for the regions of the United States so that one can get a better measure of how much various types of individuals have gained over the past 30 years, and to enable better comparisons between high government, high income states like California to low government medium income states like Texas. I don’t say this would be easy and there are lots of arguments that can be made regarding defining my standard of living metric. But when it gets down to it, what we all desire is to minimize the number of hours we have to work to achieve some basic standard of living. An hour is a conserved quantity (in the sense that in physics, mass and energy are conserved quantities.) And an hour in California is the same as an hour in Texas, and is the same as an hour in France. You cannot say the same about a dollar in California versus a dollar in Texas (or a Euro.).

That said, this article is about international comparisons…and that adds more complexity to my idea. But I think that if it could be done, it would provide a better means for comparing quality of life in different parts of the world. And I think it eliminates the problem described above regarding how to account for the GDP associated with government