Yves here. This is an interesting theory, but I’m not sure I buy it. McEndree’s argument is basically that US shale players weren’t the main target of the Saudis because they haven’t succeeded in lowering their production. The fact that the effort so far has not worked as perhaps planned isn’t proof that it wasn’t the Saudis’ aim, particularly since they said at the very outset that they as the low cost producer, should not be the swing producer.

Note I find the “main target” to be a bit of a straw man, since even at the time of the Saudi refusal to cut production to support prices, many observers (including yours truly) argued the Saudis were targeting not just the US but all higher cost producers, including its geopolitical enemies like Russia and Iran.

The mistake of the Saudis (and most oil analysts) was one not made by John Dizard of the Financial Times. Dizard correctly predicted that the shale players would keep pumping as long as they had access to financing. Indeed, as we’ve seen, they are continuing to pump strictly to keep servicing debt. And the need to produce revenues (which is the motivation for most major oil producing nations, since they need oil income to finance their national budgets) means all the producers are locked into a bad equilibrium: they are all going to keep producing at levels higher than the markets can absorb until either a deal or an external force makes them stop. With the frackers, it will be access to financing.

And what I believe McEndree also misses, but I welcome informed criticism if I have this wrong, is that fracking won’t be so easily resumed once fracking companies start hitting the wall and/or defaulting. Their old business model presupposed much higher prices and high leverage. I doubt we’ll see prices above $60 a barrel, nor will we see anywhere near as much gearing of shale gas plays as in the past. How many fields are economically viable if one assumes the odds don’t favor oil over $60 for at least the next few years, much higher levels of equity financing, and you also factor in your required equity return greater regulatory risk (curbs or outright ban in some areas due to earthquake risk and the impact on water supplies)?

By Dalan McEndree, whose career has focused on the Soviet Union and Russia, and has included fifteen years in Russia as a U.S. diplomat, in business, working both for international and Russian businesses, and in consulting. Originally published at OilPrice

Do the Saudis have an oil market strategy beyond pumping crude to defend their market share? Are they indifferent to which countries’ oil industries survive? Or, alternatively, are they targeting specific global competitors and specific national markets? Did they start with a particular strategy in November 2014 when Saudi Petroleum and Mineral Resources Minister Ali al-Naimi announced the new market share policy at the OPEC meeting in Vienna and are they sticking with it, or has their strategy evolved with the evolution of the global markets since?

And, of course, what does the Saudi strategy beyond pumping crude portend for the Saudi approach to some OPEC members’ calls for coordinated production cuts within OPEC and with Russia?

Conventional Wisdom

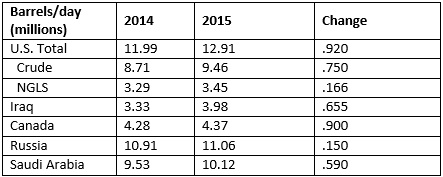

Conventional wisdom has it that the Saudis are focused primarily on crushing the U.S. shale industry. In this view, the Saudis blame the U.S. for the supply-demand imbalance that began to make itself felt in 2014. U.S. production data seems to support this. Between 2009 and 2014, U.S. crude and NGLs output increased nearly 4 million barrels per day, while Saudi Arabia’s increased only 1.64 million barrels per day, Canada’s 1.06 million, Iraq’s 0.9 million, and Russia’s 0.7 million (Saudi data doesn’t include NGLs).

In addition, the Saudis, among many others, believed that U.S. shale would be the most vulnerable to Saudi strategy, given relatively high production costs compared to Saudi production costs and shale’s rapid decline rates and the need therefore repeatedly to reinvest in new wells to maintain output.

Yet, if the Saudis were focused on the U.S., their efforts have been unsuccessful, at least in 2015. As the table below shows, U.S. output growth in 2015 outstripped Saudi output growth and the growth of output from other major producers in absolute terms. In addition, many observers also came to believe that U.S. shale production will recover more quickly than production in traditional plays once markets balance due to its unique accelerated production cycle and that this quick recovery will limit price increases when markets balance.

Is the U.S. Really the Primary Target?

The above considerations imply the Saudis—if indeed they primarily were targeting U.S. shale—embarked on a self-defeating campaign in November 2014 that could at best deliver a Pyrrhic victory and permanent revenues losses in the US$ hundred billions.

Is the U.S. the primary target? U.S. import data (from the EIA) suggests the U.S. is not now the Saudis’ primary target, if it ever was. Like other producers, the Saudis operate within a set of constraints. Domestic capacity is one. In its 2015 Medium Term Market Report (Oil), the IEA put Saudi Arabia’s sustainable crude output capacity at 12.34 million barrels per day in 2015 and at 12.42 million in 2016. Export capacity—output minus domestic demand—is another.

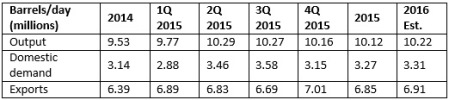

Rather than maintaining crude output at 2014’s level in 2015, the Saudis steadily increased it after al-Naimi’s announcement in Vienna as they brought idle capacity on line (data from the IEA monthly Oil Market Report): ![]()

This allowed them to increase average daily crude exports by 460,000 barrels in 2015 over 2014 average export levels—even as Saudi domestic demand increased—and exports peaked in 4Q 2015 at 7.01 million barrels per day (assuming the Saudis keep output at average 2H 2015 levels in 2016, and domestic demand increased 400,000 barrels per day, as the IEA forecasts, the Saudis could export nearly 7 million barrels per day on average in 2016):

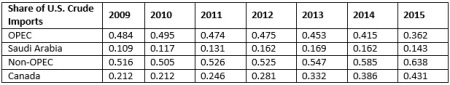

The Saudis did not ship any of their incremental crude exports to the U.S.—in other words, they did not increase volumes exported to the U.S., did not directly seek to constrain U.S. output, and did not seek to increase U.S. market share. Based on EIA data, Saudi imports into the U.S. declined from 1.191 million barrels per day in 2014 to 1.045 million in 2015—and have steadily declined since peaking in 2012 at 1,396 million barrels per day. (OPEC’s shipments also declined from 2014 to 2015, from 3.05 million barrels per day to 2.64 million, continuing the downward trend that started in 2010). Canada, however, which has sent increasing volumes to the U.S. since 2009, increased exports to the U.S. 306,000 barrels per day in 2015:

Also, the Saudi share of U.S. crude imports declined 1.9 percentage points in 2015 from 2014, and has declined 2.6 percentage points since peaking at 16.9 percent in 2013; during the same two periods, Canada’s share increased 4.5 and 9.9 percentage points respectively (and has more than doubled since 2009):

Other Markets

The Saudis presumably exported the incremental 606,000 barrels per day (460,000 from net increased export capacity plus 146,000 diverted from the U.S.) to their focus markets. Since other countries’ import data generally is less current, complete, and available than U.S. data, where these barrels ended up must be found indirectly, at least partially.

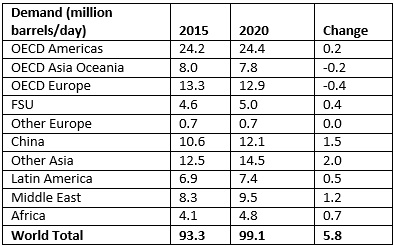

In its 2015 Medium Term Market Report (Oil), the IEA projected that the bulk of growth from 2015 to 2020 will come in China, Other Asia, the Middle East, and Africa, while demand will remain more or less stagnant in OECD U.S. and OECD Europe:

The Saudis find themselves in a difficult battle for market share in China, the world’s second largest import market and the country in which the IEA expects absolute import volume will increase the most through 2020—1.5 million barrels per day (it projects Other Asia demand to increase 2.0 million). The Saudis are China’s leading crude supplier. However, their position is under sustained attack from their major—and minor—global export competitors. For example, through the first eleven months of 2015, imports from Saudi Arabia increased only 2.1 percent to 46.08 million metric tons, while imports from Russia increased 28 percent to 37.62 million, Oman 9.1 percent to 28.94 million, Iraq 10.3 percent to 28.82 million, Venezuela 20.7 percent to 14.77 million, Kuwait 42.6 percent to 12.68 million, and Brazil 102.1 percent to 12.07 million.

As a result of the competition, the Saudi share of China’s imports has dropped from ~20 percent since 2012 to ~15 percent in 2015, even as Chinese demand increased 16.7 percent, or 1.6 million barrels per day, from 9.6 million in 2012 to 11.2 million in 2015. Moreover, the competition for Chinese market share promises to intensify with the lifting of UN sanctions on Iran, which occupied second place in Chinese imports pre-UN sanctions and has expressed determination to regain its prior position (Iran’s exports to China fell 2.1 percent to 24.36 million tons in the first eleven months of 2015).

Moreover, several Saudi competitors enjoy substantial competitive advantages. Russia has two. One is the East Siberia Pacific Ocean pipeline (ESPO) which directly connects Russia to China—important because the Chinese are said to fear the U.S. Navy’s ability to interdict ocean supplies routes. Its capacity currently is 15 million metric tons per year (~300,000 barrels per day) and capacity is expected to double by 2017, when a twin comes on stream. The second is the agreement Rosneft, Russia’s dominant producer, has with China National Petroleum Corporation to ship ~400 million metric tons of crude over twenty-five years, and for which China has already made prepayments. Russia shares a third with other suppliers. Saudis contracts contain destination restrictions and other provisions that constrain their customers’ ability to market the crude, whereas those of some other suppliers do not.

Marketing flexibility will be particularly attractive to the smaller Chinese refineries, which Chinese government has authorized to import 1 million-plus barrels per day.

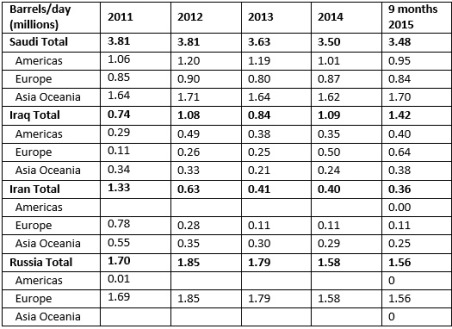

While they fight for market share in China, the Saudis also have to fight for market share in the established, slow-growing or stagnant IEA-member markets (generally OECD member countries). Saudi exports to these markets declined 310,000 barrels per day between 2012 and 2014, and 490,000 barrels per day between 2012 and 2015’s first three quarters. Only in Asia Oceania did Saudi export volumes through 2015’s first three quarters manage to equal 2012’s export volumes. During the same period, Iraq managed to increase its exports to Europe 340,000 barrels per day (data from IEA monthly Oil Market Report).

It is therefore not surprising that the Saudis moved aggressively in Europe in 4Q 2015—successfully courting traditional Russian customers in Northern Europe and Eastern Europe and drawing complaints from Rosneft.

As with China, the competition will intensify with Iran’s liberation from UN sanctions. For example, Iran has promised to regain its pre-UN sanctions European market share—which implies an increase in exports into the stagnant European market of 970,000 barrels per day (2011’s 1.33 million barrels per day minus 2015’s 360,000 barrels per day).

Might the U.S. be an Ally?

Without unlimited crude export resources, the Saudis have had to choose in which global markets to conduct their market share war, and therefore, implicitly, against which competitors to direct their crude exports.

Why did the Saudis ignore the U.S. market? First, U.S. crude does not represent a threat to the Saudis’ other crude export markets. Until late 2015, when the U.S. Congress passed, and President Obama signed, legislation lifting the prohibition, U.S. producers, with limited exceptions, could not export crude. Even with the prohibition lifted, it is unlikely the U.S. will become a significant competitor, given that the U.S. is a net crude importer. Therefore, directing crude to the U.S. would not improve the Saudi competitive position elsewhere.

Second, the U.S. oil industry is one of the least vulnerable (if not the least vulnerable) to Saudi pressure—and therefore least likely and less quickly to crack. Low production costs are a competitive advantage, but are not the only one and perhaps not the most important one. Financing, technology, equipment, and skilled manpower availability is important, as are political stability, physical security, a robust legal framework for extracting crude, attractive economics, and access and ease of access to markets. The Saudis major export competitors—Russia, Iran, and Iraq—are far weaker than the U.S. on all these areas, as are its minor export competitors, including those within—Nigeria, Libya, Venezuela, and Angola—and outside OPEC—Brazil.

Third, in the U.S. market, the Saudis face tough, well-managed domestic competitors, and a foreign competitor, Canada, that enjoys multiple advantages including proximity, pipeline transport, and trade agreements, the Saudis do not enjoy.

Finally, the Saudis may be focused on gaining a sustainable long term advantage in a different market than the global crude export market—the higher value added and therefore more valuable petroleum product market. Saudi Aramco has set a target to double its global (domestic and international) refining capacity to 10 million barrels per day by 2025. Depressed revenues from crude will squeeze what governments have to spend on their oil industries and, presumably, they will have to prioritize maintaining crude output over investments in refining.

In this Saudi effort, the U.S. could be an ally. The U.S. became a net petroleum product exporter in 2012 (minus numbers in the table below indicate net exports), and net exports grew steadily through 2015. Growth continued in January, with net product exports averaging 1.802 million barrels per day, and, in the week ending February 5, 2.046 million. U.S. exports will lessen the financial attractiveness of investment in domestic refining capacity, both for governments and for foreign investors in their countries’ oil industries (data from EIA).

Saudi Intentions

The view that the Saudi market share strategy is focused on crushing the U.S. shale industry has led market observers obsessively to await the EIA’s weekly Wednesday petroleum status report and Baker-Hugh’s weekly Friday U.S. rig count—and to react with dismay as U.S. rig count has dropped, but production remained resilient.

In fact, they might be better served welcoming resilient U.S. production. It may be that the Saudis will not change course until Russian output declines, Iraq’s stagnates, Iran’s output growth is stunted—and that receding output from weaker countries within and outside OPEC would not be enough. If this is case, the Saudis will see resilient U.S. production as increasing pressure on their competitors and bringing forward the day when they can contemplate moderating their output.

NOTE: Nothing in the foregoing analysis should be understood as denying that the U.S. oil industry has suffered intensely or asserting that this strategy, if it is Saudi strategy, will succeed.

Shale production may not have fallen as much or as quickly as expected, for various reasons, but the rig count did fall off a cliff: see for instance http://www.forbes.com/sites/arthurberman/2016/01/11/big-drop-in-rig-count-points-to-capitulation-by-u-s-shale-drillers/#637662b962da. Thus it is wrong to claim that the Saudi offensive did not succeed: this year we should finally see production plummeting and companies going bankrupt.

Thanks for the article. I’m surprised how much Saudi production increased, is it ~7%?

It seems like not a massive amount compared to the what, a ~75% drop in price ongoing… Which may have gone further south than the Saudis wanted.

Could demand destruction be involved? Both due to recession/austerity and perhaps just as significantly to greater efficiency and due to alternative energy sources?

It seems like the oil situation is a replay we see many times in the geopolitical chess game played by the oligarchs running the world. The western coalition which includes Saudi Arabia agreed to the oil price crash to take Russia, Iran and Venezuela down as a primary objective. The cost benefit analysis of this objective revealed a simultaneous take down of US frackers. Even though it was known that the US economy would suffer, and most small oil and gas players would go bankrupt, the big players such as Exxon Mobil would eventually pick up this infrastructure for pennies on the dollar, further consolidating the industry into a few players. It is the same game plan utilized many times. Saudi Arabia may have been duped as their budget shortfalls are extreme due to their actions, but the time might be right for the West to abandon Saudi as their internal political infighting due to changes in leadership might lead to chaos in the country and ME anyway..

The banks that financed the shale “revolution” will be looking for bailouts for their distressed energy loans. If this happens, yes, fracking can be “easily resumed”. If not and companies are forced to drill their cashflow, which is the sane arrangement, then you will not see a quick recovery.

I’m surprised that there are not many more commenters weighing in on this post.

Saudi Arabia playing Geopolitical Monopoly balls-out is like the appearance of the Fourth Horseman.

Is not the Petro-Dollar more or less it’s own currency? Is Saudi Arabia not simply debasing that currency in classic beggar-thy-neighbor style?

You said it: the Saudis are the low-cost producer, so why should they pound sand as the swing producer?

It is difficult to determine an answer when the facts support all possible conclusions. All we know is that the Saudis are still making a profit and almost all other producers are losing.

When I’m not sure, I tend towards Bismark & Tip O’Neill: all politics is local, foreign policy is an extension of domestic policy. The House of Saud is in disarray currently, so there is a good possibility that internal politics are dictating the policy. SA also seems to view its prime rival as Iran, for religious reasons. While that is usually considered Shia v Sunni, the Sauds are a particular branch of the Sunni tree with their own special concerns.

Point is, most sources are looking at the reasoning from a financial perspective, or a business perspective of suppressing the competition. But we lack the data to frame the question that way.

This is a must-read to understand the relationship of the House of Saud to the rest of the Muslim world:

3quarksdaily.com/3quarksdaily/2012/08/the-architects-of-the-war-on-islam.html

Your suggested must-read at 3quarksdaily.com was eye-opening — to me, anyway. And very enjoyable reading, too, given the many new (again, to me) words and phrases in its language.

I concede that I am out-of-my-depth in sussing out the chain(s) of symptom(s) vs. cause(s) — due to insufficient knowledge of history and political economy in the Middle East.

Your point about framing is well-taken. I used a frame-of-convenience, which jumped towards a conclusion that you rightly mark as speculative rather than strongly supported by data.

I think that’s right. Its the Saud family saying “when it comes to energy you come to us”

To me, it was obvious from the start that Russia was the real target of the Saudi price cuts. The Obama administration is at best indifferent, as the folks in oil producing areas of the US are not undecided voters in swing states.

Like lots of folks who never had to work for a living, I don’t think that the House of Saud thinks in economic terms.

The Saudi oil minister, Ali al-Naimi, ” said much the same thing in a press interview, arguing that it was “crooked logic” for low-cost producers such as Saudi Arabia to pump less to balance the market.

Supply was only half the calculus, though. While the new Saudi stance was being trumpeted as a war on shale, Naimi’s not-so-invisible hand pushing prices lower also addressed an even deeper Saudi fear: flagging long-term demand.

Naimi and other Saudi leaders have worried for years that climate change and high crude prices will boost energy efficiency, encourage renewables, and accelerate a switch to alternative fuels such as natural gas, especially in the emerging markets that they count on for growth. They see how demand for the commodity that’s created the kingdom’s enormous wealth—and is still abundant beneath the desert sands—may be nearing its peak. This isn’t something the petroleum minister discusses in depth in public, given global concern about carbon emissions and efforts to reduce reliance on fossil fuels. But Naimi acknowledges the trend. “Demand will peak way ahead of supply,” he told reporters in Qatar three years ago. If growth in oil consumption flattens out too soon, the transition could be wrenching for Saudi Arabia, which gets almost half its gross domestic product from oil exports.”

http://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2015-04-12/saudi-arabia-s-plan-to-extend-the-age-of-oil

——————————————————————————————-

This is the 3rd oil shock to hit the world. The first 2 in the 1970s were embargoes, a constriction on supply to the US, and its chief allies, the UK, Canada, Japan. The 3rd shock is an overproduction, a glut producing plunging pricing from the demand side. It is deliberate as the first 2 and with desired consequences in mind, as well as other consequences that may or may not be relevant or desirable but are the concomitant fallout of the primary goals that need to be accomplished. There are short and long term goals but both are united by the concern for peak demand, not peak supply or competition. Eventually, demand will fall due to destruction by the rise of electric cars and trucks, electric mass transit, and the pollution concerns driving nation policy as formulated by the recent Paris UN Climate Conference, COP21.

Buried in COP21 are agricultural concerns of soil conservation due to over dependency on petro-chemical inputs for food production. Spain has a national transportation policy to integrate its national population by the elimination of great distances and the time needed to travel, that mimics the Interstate Highway System of the US from 1950s, but uses mass transit of bullet trains powered by a growing electrical system built in its desert areas to build out Concentrated Solar Power plants.

That leaves materials such as plastics as the diminishing market for crude oil in the long term future. Saudi Arabia plans to extend the oil age for as long as possible and for as long as possible be the chief supplier for whatever little demand remains as it shrinks over time. That is driving the strategy for lowering the price of crude in world markets. It seeks to find a price level that will soon destroy competition and send the message that this exercise will be quickly and mercilessly renewed if needed. So bankers will be warned off if they seek to finance this again in the future. It also seeks to find a price level soon thereafter to allow for demand to stay steady enough to be affordable and mitigate the too rapid adoption of a green economy spurred by cost savings from too highly priced crude. The sweet spot in pricing therefore leaves the fewest operating competition and the most customer retention, forestalling their abandonment of crude oil for cheaper, cleaner alternatives as long as possible. Every drop of oil under the sands of Saudi Arabia will never be sold, but enough will to ensure its transition to another economic platform, one powered by solar energy which ironically will displace it as a geo-political powerhouse.

In the short term, a global market does not insulate the US or Russia from the shock of over supply. Countervailing social forces in the US, such as access to financing to prop up the continued drilling which is driven more by debt service than market demand are the variables which makes simple targeting of this or that competitor not an easy exercise as punching in GPS coordinates and launching a drone strike. This is politics, it requires the often denigrated multi-dimensional chess, but as you can see, the power of politics, in decision making to flood the world with crude oil is as real as the power that comes out of a barrel of gun or the money which makes the world go round. Politics is slowing the velocity of money by crushing the price per barrel and causing the barrel of the gun to be seen as a better way forward than the placid civil society compromises and stagnation. This is a way of saying the Saudis are playing with fire and risk burning the whole world down in addition to the particular targets of competition in the short term. They may emerge with most of what they want in the face of terrible organized opposition retaliating, and they probably will relent at that juncture, having made the their point with the bankruptcies of many US tight oil producers and carnage in the national budgets of Russia, Mexico, Venezuela and others. And of course, their good customers in China and India more than happy to do business with them after the Arabs humiliated many and American oil executives and many a Russian oligarch.

Very well put. Elon Musk and his battery plant are the long term targets while their oil competition and geopolitical rivals suffice in the short term. Impressive strategy. Perhaps they follow Henry as well.

Solar power and electric cars must scare the heck out of the Saudi royal family.

The main point is being missed by everyone. As Sheik Yamani quipped a while ago, “The stone age didn’t end because they ran out of stones.” The oil age is ending because of the lethal combination of climate catastrophe and explosive cost-reducing technological progress in the production and storage of non-hydrocartbon, renewable, energy. So the imperative for every hydrocarbon producer–the Saudis, perhaps, most of all–is USE IT OR LOSE IT. This is unprecedented in economic history–indeed in all human history–and the way this argument is being carried on here in terms of conventional economics is like the Blind Men Describing An Elephant.

perhaps the saudis have an oil production peak they’re not letting on about……..there’s been past speculation concerning the amount of petroleum reserves, actual vs implied. I think they are trying to kill the competition now, so as to maintain swing production, and thus infuence, in the future.

I meant to add also the desire to destroy Iran, being that they have oil (and gas) which may/is helping to bump SA down several notches in geopolitical influence.

If that is the strategy, there’s an obvious reason it could rebound on the Saudis. By this logic, they should be calculating that as a much wealthier country with a much bigger cushion of financial reserves,they could withstand the shock better than the Russians or Iranians. The obvious flaw is that while this is true, when you look at the overall political economies Iran and Russia are clearly much more resilient. Iran has the recent experience of a decade of sanctions, and Russia of the collapse of communism, and in both cases the historical memory extends further back to even deeper devastations. So you might expect that a given level of revenue decline might actually cause more disruption in the relatively pampered Saudi system than in its competitors, even though it looks less threatening on paper — and I think you can already see signs of that.

This is a curious piece of conjecture against the backdrop of oil’s biggest one-day rise in 7 years – courtesy, we are told, of a statement that came out of UAE yesterday to the effect that OPEC was considering output cuts, started a huge oil rally that promptly fizzled when WSJ essentially walked it back, but was given new and vigorous life today, I believe due to the announced cease-fire in Syria (which presumably would put on hold what had been an imminent Turkish and Saudi foray into Syria.

I don’t buy the author’s ‘theory’ at all, i.e., that the Saudis had in mind capturing the more value-added portion of the export market as a goal. Maybe they’ve played with the notion since increasing production in late 2014 for different reasons, and perhaps hope to offset the heavy losses incurred over the past year by ramping up petroleum products, but they hardly needed to throw the whole global economy into a spin to make such a longer-term strategy work.

I think there is some real merit to the notion the Saudis are also targeting clean energy alternatives as a whole, but again, the other matters afoot that form the backdrop of this move to me weigh much more heavily: the move was timed perfectly with the Fed’s first indication of ‘tightening’, which had the effect of driving the US $ so high while oil fell so low it has brought much of the globe to the brink in a reassertion of US financial (dollar) primacy that took the already overvalued Yuan with it. China was already well into a bubble collapse with massive ensuing capital flight. China’s subsequent devaluations have already brought tumult across global markets – and there is every expectation that they will be forced to devalue much further so long as oil is low and the dollar strong.

The Saudis principal target in my view was and is Russia, and that in coordination with the US. Neither Obama or anyone else in the G7 has held the Saudis’ foot to the fire about this move, as I believe it was ‘our’ miscalculation from the outset vis a vis the Russians, Iranians and Syrians as to how much Russia et al were prepared to put on the line and for how long. This meant G7 oil producers (Norway, UK, Canada, US) were going to pay a great deal more for ‘getting Putin’ than the ‘get’ was ultimately going to be worth. That Obama’s Admin was also less than enamored with fracking was an additional factor to be weighed in the equation. For Obama, what was economic and political ‘pain’, and the prospect of some real environmental ‘gain’ almost entirely taking place in ‘red States’ was OK for 2015, but this year it’s going to be a much bigger deal.

The market clearly sees the standoff in Syria as tied directly to Saudi decision-making on oil price – ISIS and the other jihadist groups in Syria are about washed up, and the US/Saudi/NATO regime change gambit in Syria has clearly failed. Should the Saudis and Turks actually enter Syria in numbers, we’re headed straight into a major war – but it appears the Saudis, Turks et al may finally have realized removing Assad in exchange for losses already in the hundreds of billions with an option for an even more disastrous war is just too high a price to pay. We’ll see.

Fiver have you considered the actions wrt these events might have wrt Russian increasing weapons development e.g. the upgrades on existing platforms and the likes of the T-14, aircraft and missile.

Especially with the Ukrainian situation plus their failed MIC dramas…

Well, I know the portion of Ukraine that voted to not recognize the legitimacy of the regime in Kiev (I also do not recognize its legitimacy) was important to the Russian MIC and now lies in abject ruin. It would take time to build new facilities to fabricate parts, components, etc., or to re-source them from elsewhere given the sensitivity of weapons technology. Perhaps that would be an added impetus to upgrade specific program output. In any case, my take is Russia under Putin, or any probable successor to Putin, will spend what it takes to be an independent Russia. In this I do not see an ‘equivalence’ in the respective roles played by the MIC in the US vs the MIC in Russia. One is built to oversee a global Empire, the other to at best keep itself dangerous enough to deter a direct attack – and these days there are plenty who believe the Russian MIC is no longer that dangerous.

Yeah pretty much here too… w/ the Russian product fit for purpose in shorter time frames, less expensive, easier to roll out and as you note defensive in orientation.

Skippy… yet in America its throw out what works and become bogged down in pie in the sky.

Except…the Russians are going bankrupt, and Putin’s regime is cracking at the edges. One thing you left out, with sanctions lifted in Iran, they are no longer reliant on Russia for assistance as in the past. Russia has fallen into a trap of their own design. Obama has lucked out.

Russia is indeed under serious financial strain due to the low oil price (sanctions a peanut in relative terms) but so is everyone else – and there is zero, and I do mean zero, prospect of the regime folding barring a debacle, eg., the Russian forces in Syria are destroyed. What you and the conventional thinking in the West leave out is that Putin believes (and for very good reasons) that he is in the right, it is Russia that has acted legitimately, etc., and both the key Russian oligarchs and people are solidly behind him. It’s the difference between knowing Vietnam was a lost cause after the French were booted out in 1954, and discovering that in 1975 after 20 years of efforts to terrorize/bomb the Vietnamese into submission – the Russians are a people and a nation and know perfectly well just how badly screwed over they’ve been.

As for Iran, I see that argument floated here and there without the least shred of evidence to support the contention – Iran wants to normalize relations with the world and Russia has been critical to the success of that effort.

That all said, it appears my thought that it was the ‘ceasefire’ that prompted such a huge rally in prices may have been mistaken (we’ll see next week). As both Turkey and the Saudis are reported today to be on the brink of major military incursions into Syria, the price spike may mark a return of a ‘war premium’ to oil pricing – which would explode if the Saudis actually begin air strikes as threatened.

This is an extremely dangerous situation and if Obama has any luck left to him Erdogan in Turkey and the reckless young Prince calling the shots in Saudi Arabia will come to their senses.

Having just read Svetlana Aleksitjevits “War’s Unwomanly Face” – http://www.nybooks.com/daily/2015/10/12/svetlana-alexievich-truth-many-voices/ – which I had for Chrismas, I would be careful of believing that Russia “is going bankrupt” and “Putins’ regime is cracking” …

The Russian capacity for sucking up suffering and carrying on regardless is endless; The Russians are not a people that can be defeated by inconveniences like a mere lack of money or a poor standard of living – this is a Western idea, based on Western (wishful) thinking.

We are much more concerned about these things than the Russians are and we are much, much more fragile – right now – it’s the over-leveraged Danish factory farms who are suffering over a mere loss of 1.2 % turnover due to Russia, on the Russian side they will suffer fewer heart attacks and cases of MRSA CC 398 and they will “grow their own pork”.

Russia has oil, so, Russia does not need USD and Russia has good trade relations with China who makes pretty much everything else that one could buy for USD including whatever the West could offer.

I think that re-invoking the cold war was a huge stupidity on the part of the EU – It should be clear to everyone that the USA is now being embroiled in the same mess (corruption, useless empire) as the USSR once was and it’s time to swim away from the sinking ship in good order, not tie oneself to it!

Couldn’t reducing ISIS’ earnings from oil to weaken them be one major objective of the Saudis?

No.

1. No one should be surprised the shale players kept producing in spite of the price, as that was exactly what they said they would do: kick the debt can down the road as long as they could continue financing their financing with more financing. It is, after all, the standard US business model.

2. Shale financing (and tar sands for that matter) has always only been available when oil prices crossed a certain tipping point and promised to stay above it for awhile. When prices inevitably sank below the tipping point, financing dried up along with operations.

Agree …. and …. when someone goes “tits-up” in the US, they are not shunned and banished forever for their incompetence. On the contrary, a few battle-scars are good for the next round of financing.

I.O.W. A shale producer goes bankrupt, “the next day” it reopens under new(ish) management with a better price-point because some (perhaps most) of the old debt was discharged by the bankruptcy.

It will take a decade of year-on-year losses to kill the shale producers. Saudi doesn’t have a decade .

Actually, they have about seven years, according to estimates. They’ve already been going for one year. It’s long enough to kill the shale producers, most of whom were scam artists anyway.