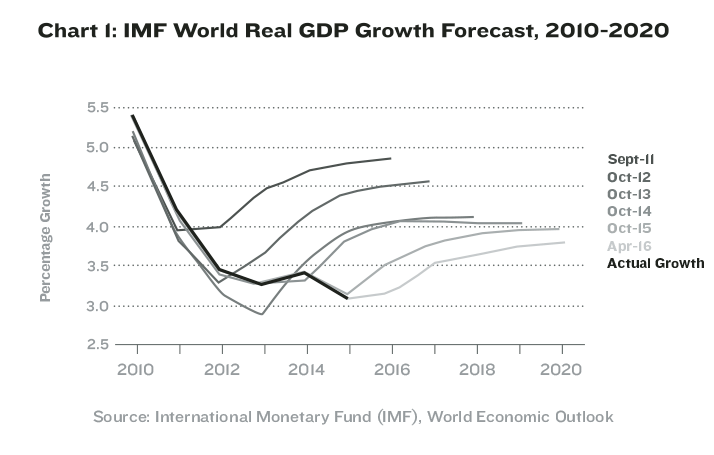

Yves here. Get a cup of coffee. This is an important, comprehensive and well-argued article. It correctly focuses on the fact that the danger in indebtedness is private sector debt, and why that risk looms so large, particularly in China.

By Richard Vague, Managing Partner, Gabriel Investments. Originally published at Democracy Journal

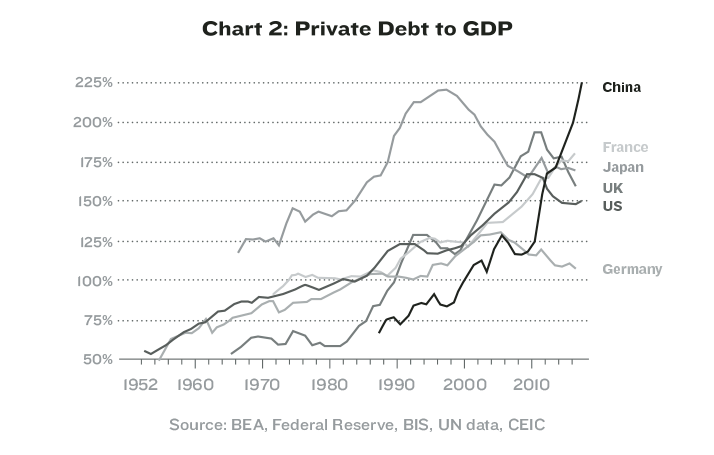

One of the key and largely overlooked reasons for this disappointing growth is hiding in plain sight: the increasing global burden of private debt—the combination of business debt and household debt. Even though government debt grabs all the headlines, private debt is larger than government debt and has more impact on economic outcomes. In the United States, total nonfinancial private debt is $27 trillion and public debt is $19 trillion. More telling, since 1950, U.S. private debt has almost tripled from 55 percent of GDP to 150 percent of GDP, and most other major economies have shown a similar trend. [See Chart 2.] Since GDP is largely the sum of all the spending, and thus income, of households and businesses in an economy, if aggregate private debt to GDP has tripled, that means that average businesses and households have three times more debt in relation to their income. Both private debt and government debt matter, and both will be discussed here, but of these two, it is private debt that has the larger and more direct impact on economic outcomes, and addressing the issues associated with private debt is the more productive path to economic revival.Stagnant incomes, underemployment, and job insecurity are key reasons so many voters in Europe and America are now willing to embrace candidates outside of the mainstream. But the now stultifying level of private debt, and the accompanying impact on growth, is an equally important reason.

One of the key and largely overlooked reasons for this disappointing growth is hiding in plain sight: the increasing global burden of private debt—the combination of business debt and household debt. Even though government debt grabs all the headlines, private debt is larger than government debt and has more impact on economic outcomes. In the United States, total nonfinancial private debt is $27 trillion and public debt is $19 trillion. More telling, since 1950, U.S. private debt has almost tripled from 55 percent of GDP to 150 percent of GDP, and most other major economies have shown a similar trend. [See Chart 2.] Since GDP is largely the sum of all the spending, and thus income, of households and businesses in an economy, if aggregate private debt to GDP has tripled, that means that average businesses and households have three times more debt in relation to their income. Both private debt and government debt matter, and both will be discussed here, but of these two, it is private debt that has the larger and more direct impact on economic outcomes, and addressing the issues associated with private debt is the more productive path to economic revival.Stagnant incomes, underemployment, and job insecurity are key reasons so many voters in Europe and America are now willing to embrace candidates outside of the mainstream. But the now stultifying level of private debt, and the accompanying impact on growth, is an equally important reason.

Private debt is a beneficial and essential part of any economy. However, as it increases, it can bring two problems. The first is dramatic. Very rapid or “runaway” private debt growth often brings financial crises. Runaway private debt growth brought the 2008 crisis in the United States, the 1991 crisis in Japan, and the 1997 crisis across Asia, to name just three. And just as runaway debt for a country as a whole is predictive of calamity for that country, runaway debt for a subcategory of debt, such as oil and gas or commercial real estate, is predictive of problems within that subcategory.

The second problem it brings is much more subtle and insidious: When too high, private debt becomes a drag on economic growth. It chips away at the margin of growth trends. Though different researchers cite different levels, a growing body of research suggests that when private debt enters the range of 100 to 150 percent of GDP, it impedes economic growth.

When private debt is high, consumers and businesses have to divert an increased portion of their income to paying interest and principal on that debt—and they spend and invest less as a result. That’s a very real part of what’s weighing on economic growth. After private debt reaches these high levels, it suppresses demand.

Because interest rates are low, some economists have dismissed this impact. However, most middle- and lower-income households (which is where the highest rate of debt growth has been), as well as most small- and medium-size businesses, pay interest rates much higher than money market rates. In the case of low-income households and small businesses, the rates for some types of debt can be very high, often an APR of 20 to 30 percent or more. And in addition to interest, all these borrowers have to pay down the principal balance of the loan. High debt makes these borrowers more reluctant to spend or take on more debt. Further, an estimated 6.4 million of the 56 million mortgages held in the United States are still severely underwater. Millions more are less severely underwater or just barely “above.” Many of these mortgages were underwritten at the height of the boom. Since then, the home values, and in many cases the incomes, of these borrowers have fallen. Lower rates may help but do not solve their financial stress. Though their rates may be lower, all of these borrowers are now in a world where increases in income and revenue are harder to come by.

This all takes a bite out of the spending and investing that drives growth.

The unprecedented amount of our global debt glut is underscored by the creeping presence of negative interest rates—a situation where the borrower, unbelievably enough, gets paid for borrowing. An estimated 15 percent of European corporate debt issued now has a negative interest rate. If the massive $150 trillion glut of debt is the culprit that is curbing demand, then perhaps this European Central Bank experiment with negative rates is the inevitable response to this glut. High private debt contributes to lower rates by reducing demand for credit—since highly leveraged borrowers have less ability to borrow more and are often understandably wary of further borrowing. But these negative rates are not generally available to low- and middle-income borrowers.

U.S. private debt growth has disproportionately affected the least well-off Americans. In fact, since 1989 (the year the Fed started a survey of this statistic), the debt level of the 20 percent of U.S. households with the lowest net worth has grown two and a half times faster than all other households. And though consumers have deleveraged since the crisis, and the popular perception is that consumers are in much better shape today, consumers are in fact carrying 13 percent more debt as a percent of GDP than they were in 2000, the moment before the ill-fated private debt boom that led to the 2008 crisis began.

As mentioned, GDP roughly equates to the aggregate spending and income of the businesses and households in a country, and the private debt of a country is the sum of household and business loans. So to speak about the “private debt to GDP ratio” of a country is essentially the same as speaking about the “private loan to income ratio” of that country. You’ll recognize that ratio, because it is the same one that lenders have long used to help make loan decisions for individuals and businesses. Whether you are applying for a loan as an individual or for your business, if your loan-to-income ratio is low, the lender is likely to conclude that you have capacity for more debt, and if it is high, the lender will likely conclude that you will struggle to pay your existing loan, much less qualify to take on additional debt.

It follows directly that if a country’s private debt to GDP ratio is low, let’s say 50 percent, then the households and businesses in that country generally have low loan-to-income ratios and are well positioned to power growth through increased leverage. And if a country’s private debt to GDP ratio is high, let’s say 200 percent, then the households and businesses in that country are generally overleveraged, with, on average, very high debt ratios. They are much less likely to be able to boost growth through more borrowing.

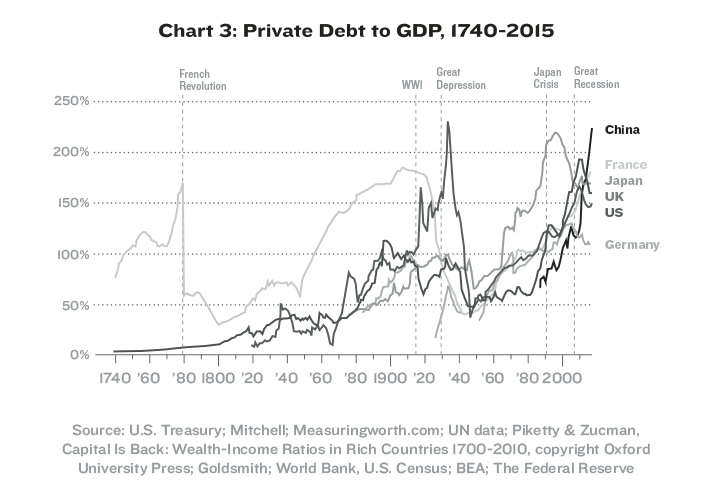

Chart 2 showed that private debt to GDP in major economies has been growing rapidly since World War II. However, it has been growing in size relative to GDP for a lot longer than that. It’s part of a process often described by economists as “financialization” or “financial deepening,” an increase in the size of a country’s debt and equity markets usually explained as simply the maturation of a market. But as we have seen, when it comes to debt, it is much more than that—it is the path from low leverage to overleverage for the participants in that economy. The benefit of increasing leverage from low levels has played a central role in the miraculous gains in incomes over the 200-plus years since the Industrial Revolution. You can see this clearly in Chart 3. I have made a concerted effort to reconstruct more than 200 years of private debt history for the six countries in this chart—China, Japan, Germany, Britain, France, and the United States—because collectively, they have accounted for roughly 50 percent or more of global GDP since the Industrial Revolution. So studying the data of these six countries during this period gives us a fairly solid proxy for the world during the most important era of economic history. (This chart is a work-in-progress which will be augmented and refined in preparation for an upcoming book on this same subject.)

All six countries show more moderate levels of private debt in the early years of this period and much higher levels today, punctuated by crescendos of private debt at pivotal moments—the French Revolution, the crisis of 1914 that began immediately prior to World War I, the Crash of 1929, Japan’s crisis in the early 1990s, and the Great Recession. These crescendos are often followed by periods of rapid and painful private debt deleveraging, such as during the Great Depression. Notwithstanding the peaks and valleys along the way—all instructive and worthy of deeper study—the general trend is toward higher levels of debt. And the world has now reached a point where combined global government and private debt to GDP is the highest by far in history.

As mentioned, short bursts of runaway growth in private debt have often led to crisis—the United States in 2008 and Japan in 1991 to name just two. That is because so much lending occurs that it results in overcapacity: Far too much of something is built or produced—housing and office buildings are two examples—and too many bad loans are made. In fact, so many bad loans are made that they approach or exceed the amount of bank capital in the system. So, inevitably, the economies of these countries need to slow to a crawl to allow demand to catch up to this overcapacity, and the banks need to be propped up or rescued because of the extraordinary amount of bad debt.

Some economists maintain that this buildup in private debt is not a concern, because for every borrower there is a lender and therefore it all balances out. This view ignores the fact that the vast majority of lending is made by a very small handful of large institutions whose increased consumption is unlikely to match the decreased consumption of overburdened borrowers, especially in the same period as that decreased consumption. Instead, their consumption is more likely to appear as retained earnings for those institutions. Further, this view ignores the disproportionate burden of this debt on middle- and lower-income groups, the very ones we depend on to power growth.

Importantly, the role and importance of private debt has been marginalized in the two leading economic policy camps. That’s why they both failed to forecast the crash of 2008. The “doves,” who favor government management of the economy through interest rates and deficit spending, were confident the future held a continuation of the supposedly benign economic era they had termed the “Great Moderation,” which ran from the mid-1980s to the mid-2000s and was characterized by low inflation, steady expansion, and decreased business-cycle volatility. The “hawks,” who prefer a hands-off policy on the part of government and strongly oppose government deficits, made dire forecasts of much higher inflation because of the high levels of government debt. But neither focused much on private debt, and the predictions of both were far off the mark.

What greater indictment can be made of an economic theory than that it failed to forecast the greatest economic calamity in 70 years? Yet both schools of thought remain largely unchanged and unrepentant. Both schools minimize the importance of private debt because public debt seems inherently and more appropriately to be our collective responsibility, while private debt seems more the responsibility of free enterprise and the marketplace. Further, the primary locus for training and influence on economists has long been the Federal Reserve, which is one step removed from private sector loans and primarily deals with government debt and bank reserves, and therefore thinks of the world in those terms.

The Global Impact of Chinese Debt

Because this current private debt burden suppresses spending and investment, growth rates in the United States, Europe, and Japan—which have private debt-to-GDP ratios of 150 percent, 162 percent, and 167 percent ,and 2015 real growth rates of 2.4 percent, 1.9 percent, and 0.5 percent, respectively—will continue to lag. Real U.S. growth rates were 1 to 2 percentage points higher for most of the post-World War II period. Even a 1 percent higher growth rate in the eight years since the crisis would have resulted in $1.2 trillion more in GDP today. And now China is on the verge of joining this mediocre-growth club.

As I forecasted in this journal in early 2015 [see “The Coming China Crisis,” Issue #36], China is now beginning to suffer the consequences of its recent private debt binge. Since 2008, it has poured on $18 trillion in new private (or nongovernment) loans. The proverbial chickens have begun to come home to roost. In the summer of 2015, China’s stock market collapsed by 45 percent. Its economy is decelerating. Its skyrocketing private debt ratio has now reached 231 percent, bringing a level of overcapacity that makes a continued slowdown in its growth inevitable in order for demand to catch up to a now-staggering oversupply of housing, commodities, and other items.

As recently as 2011, China’s growth rate was 15 percent, but is declining and is now reported by Chinese authorities as 6.7 percent, though many prominent analysts believe it is 4 percent or less. In its rush to grow, China has simply built far too many buildings—witness the many ghost towns—and produced far too much steel, iron, and other commodities—and made far too many bad loans in the process. Its overcapacity is so pronounced that it will take years for true demand to catch up with this oversupply. That’s a central part of the reason the IMF keeps overforecasting global growth. The IMF is having difficulty accepting the amount of correction that will be required.

There is, however, a major complication in all this: In spite of all rhetoric to the contrary from its leaders, China is compounding the problem by fully continuing to overlend and overproduce, albeit with diminishing returns. China’s nongovernment loans have grown almost a trillion dollars in the most recently reported period alone, and they are still producing 40 percent more steel than the world needs. In continuing this trend, the Chinese are taking a problem whose size and scope is unprecedented and making it all that much bigger.

Because China is still pouring it on, it continues to boost some growth and provide some support to commodity prices. However, in so doing, its eventual problem will be both worse and longer lived. While there are differences between China and Japan, it is worth noting that Japan’s crisis of the 1990s took eight years to unfold. After very high GDP growth in the 1980s, fueled primarily by runaway lending, Japan suffered a stock market crash in 1990, then a real estate collapse in 1991, and finally a bank rescue in 1998. And Japan has posted almost 20 years of near-zero growth since that rescue.

China’s ultimate problem is twofold. First, its growth rate will continue to slow to very low levels, perhaps, similar to Japan, for as long as a generation. Second, the oversupply will continue to mean downward long-term pressure on major nonagricultural commodity prices—in an ugly word, deflation.

This slowdown in growth will spill over to the rest of the world—contributing to the continued mixed growth results in the United States and Europe. China’s unfolding crisis will not lead to something like the 2008 meltdown, since that event stemmed from runaway private debt growth in countries representing more than half of the world’s GDP. But it won’t be small either, since China and other runaway lending countries that are economically intertwined with China such as Australia and South Korea together constitute more than a quarter of the world’s GDP.

The most immediate impact of China’s slowdown will be a dampening of the economy in other parts of the Asia Pacific region, such as South Korea, Australia, Thailand, Vietnam, Singapore, and even Japan.

Africa and South America will continue to be profoundly impacted too, because both continents are disproportionately dependent on commodity exports. Take South America, where real GDP growth has collapsed in the last five years from more than 5 percent to less than 1 percent, due as much to reduced demand from China as from any other factor.

The United States, Europe, Japan, and China—the big four—together constitute almost 65 percent of world GDP. These four have collectively been the engines that have powered global growth in the post-World War II era. But of these four, only China has shown rapid growth in recent years. China’s growth is now decelerating and will trend much lower in coming years. All four are now overleveraged and as a result will find it very hard to return to high growth. So what will be the next source of global growth? The growth of most of the rest of the world, largely Africa, South America, Southeast Asia, and the Middle East (which are collectively much smaller than the big four in economic terms) is driven in large measure by exports of raw materials, component parts, and commodities to these big four. So their growth will be muted as well. India is sometimes mentioned as a potential driver of economic growth, but it is only 3 percent of world GDP, so even if it has high growth, the impact globally will be small.

Given this high global leverage, it is not unreasonable to think that the world’s combined real growth rate will stay moderate or low for a generation. Welcome to the new era of subpar growth.

How to Solve the Problem

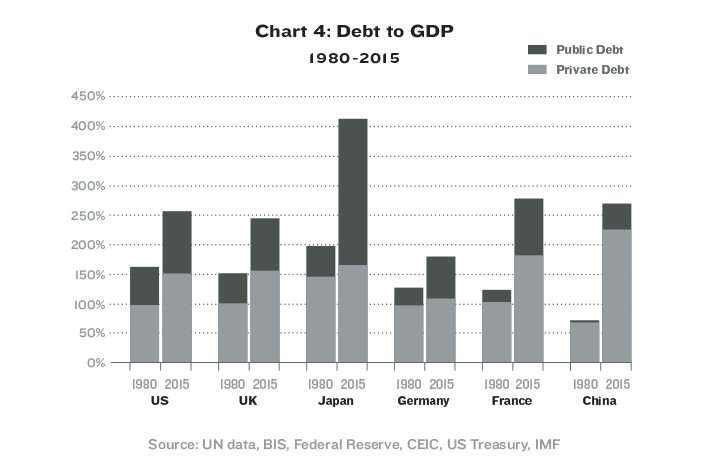

So how does a country deal with the problem of too much private debt—a task often referred to as deleveraging? This question does not currently appear on any policymaker’s agenda. However, as is easy to see from Chart 4, this will be one of the defining questions of the upcoming age.

Although I believe public debt deleveraging is a less pressing issue than private debt deleveraging—after all, governments can always resort to printing money, while households and businesses can’t—they will both be a very big part of what defines the economic era ahead. Let’s briefly examine them both.

The first thing to understand, however, is that in developed countries over any sustained period, total debt grows at a rate roughly commensurate with or greater than GDP. In fact, private debt alone usually outgrows GDP. As I will discuss below, the exceptions to this are when there is very high inflation, a high level of net exports, or a calamity such as depression or financial crisis.

Debt grows as much or more than GDP because it is a necessary and causal factor in GDP growth. It’s one of the axioms that must be understood to grasp the modern world. For example, during the “Great Moderation” period from 1985 to 2002, the GDP grew by $6.6 trillion, but total debt grew by $14.9 trillion, taking America’s total debt ratio from 155 percent to 198 percent. Private debt alone grew by $10.7 trillion. Moderation indeed!

In fact, the most benign period of U.S. debt growth since the aftermath of World War II was 1958 to 1968, when total debt declined on a percentage basis from 130 percent of GDP to 126 percent—a trivial amount of deleveraging. Even then, however, absolute debt outgrew GDP. But given even these rare moments of slight deleveraging, the path of debt in that overall postwar period has consistently been toward dramatically higher levels—doubling from 127 percent in 1951 to 255 percent today.

Some economists assert that establishing causality from debt to economic growth is difficult. That may well be so. Nevertheless, in my everyday experience over 40 years in business, as the CEO of three businesses and then as a private investor, the majority of the companies I am familiar with depend on debt for growth and expansion. In fact, without debt, most economic activity would grind to a halt. If you want to buy an office building or a house, it usually requires a loan. If you want to open a new store or expand a factory, it usually requires a loan. In a recent example, the installation of solar panels on residential homes was a small business propped up by government subsidies, until the financial industry figured out a way to offer homeowners a 20-year lease on those solar panels and the business took off. The list of examples is endless. Finance—the making of loans—is as central as any factor in driving economic growth.

Debt, especially private debt, is vital to powering growth. Yet when it gets too high it begins to impede growth, a phenomenon I refer to as the “paradox of debt.” Debt is necessary for growth, and countries with low levels of private debt to GDP are well-positioned for strong growth, by using increased private debt for things like new factories and housing. It is only when debt has piled up to levels that are too high (often after years of runaway or profligate lending), that debt becomes a burden. So when debt gets too high, how does a country deleverage—decrease the amount of debt relative to its GDP—without putting a dent in economic growth?

Politicians, when confronted with the problem of government debt that is too high, often respond by saying that we will simply grow our way out of the problem. Unfortunately, it’s not that simple. Let’s look at the historical data to see how both public and private deleveraging has actually been accomplished.

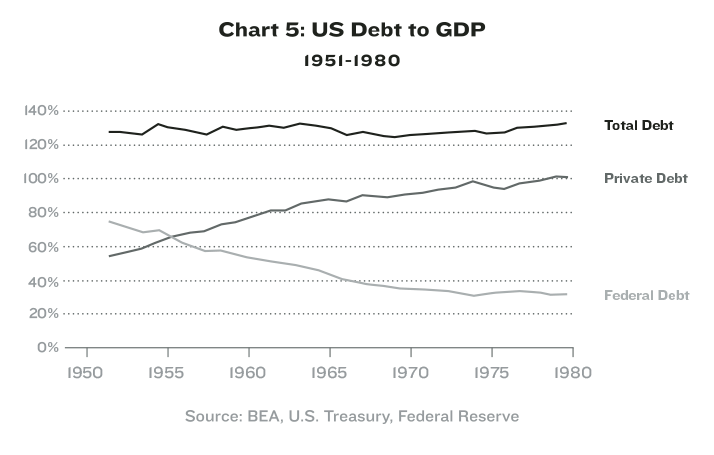

Start with public debt deleveraging, since it is the type of debt that garners the most attention. Economists and politicians often cite the post-World War II period as a triumph of government debt deleveraging. In the 30 years from 1951, a point just beyond the wind-down of World War II, to 1980, the beginning of the Reagan era, federal debt to GDP declined from 73 percent to 32 percent (it is now back to 105 percent). What these experts generally either don’t notice or neglect to mention is that private debt increased dramatically during this period, from 54 percent to 101 percent, entirely offsetting the decline in government debt. It was that offsetting leveraging that allowed the public debt ratio to come down. Otherwise we would have had massive GDP contraction just like in the Great Depression. From 1951 to 1980, a huge $2.7 trillion increase in private debt powered a $2.5 trillion increase in GDP, such that even though public debt grew by $653 billion, it declined in ratio to GDP. But total debt increased in ratio to GDP. The GDP growth resulting from that private debt growth is what allowed the federal debt ratio to decline without causing a contraction in GDP.

In fact, offsetting private leveraging is usually the mechanism that enables the ratio of public debt to come down. So, for example, we may find that a given country’s GDP grew by $30 billion, but public debt grew by only $10 billion, thereby improving that country’s public debt ratio. When we examine countries comprehensively, what we will generally find in a situation like this is that private debt will have increased by $20 billion or more in the same period, filling the “gap” left by slower public debt growth. In this example, it took a full $30 billion in total debt growth—$10 billion public and $20 billion private—to obtain this $30 billion in GDP growth. The exceptions to this are when there is very high inflation or a large net export position.

To understand this more fully, I examined a database that includes available data from 1945 onward for 47 of the largest 71 countries, including the 20 largest. (Historical private debt data is missing for certain countries, underscoring the lack of attention to this subject.) These countries together constitute 91 percent of world GDP. For these countries, since World War II, there have been a total of 42 cases where public debt to GDP (and not also private debt) has declined by at least 10 percentage points in a five-year period.

By my reckoning, in 33 of these cases, this deleveraging was due largely or wholly to increasing private debt leverage—not the most desirable way to achieve that end. Stated differently, on a ratio basis, private debt increased as much or more than public debt decreased, and therefore overall debt stayed high. In the next eight cases, the deleveraging was due to high inflation. Inflation does work, but it is a painful path to deleveraging. In the one remaining case, Saudi Arabia from 1999 to 2014, the deleveraging was due to massive positive net oil exports. In no case was the deleveraging accomplished without one of these three factors—rapid private debt leveraging (which in many cases led to a financial crisis), high inflation, or a very large net export position. None. Both private debt leveraging and high inflation are steep prices to pay for public deleveraging. A high net export level is a better path, but it is the very thing that contributes to the global imbalances that economists have so heavily criticized. It generally only occurs in smaller countries, and is very difficult for larger countries to sustain without political repercussions, as with China in the 2000s or Germany in the current, contentious EU. In any event, in its entire history, the United States has never had a sustained export surplus of the size required for meaningful public debt deleveraging.

The story is similar for private debt. Private debt deleveraging has usually only been possible because of offsetting public debt increases. Japan’s private debt ratio reached a whopping 221 percent in the lead up to its 1990s crisis. But luckily for Japan, its public debt ratio at that time was only 86 percent. In the two decades following Japan’s crisis, private debt has deleveraged from 221 percent to 170 percent (which is still too high), but that deleveraging was enabled by a massive increase in the public debt ratio from 86 percent to 246 percent. Private debt declined by ¥260 trillion, but public debt grew by ¥810 trillion, and the combined impact of this debt increase was growth of zero in nominal GDP.

Again, just one example, but I have surveyed all the available data for these same 47 countries, and since World War II, there have been a total of 40 cases in which private debt to GDP (and not also public debt) has declined by at least 10 percentage points in a five-year period. By my reckoning, in 24 of these cases, the deleveraging was due largely or wholly to increased public debt leverage. In eight more cases, the deleveraging was due to high inflation. In the eight remaining cases, the deleveraging was due to a large, positive net export position. In no case was the deleveraging accomplished without one of these three factors—rapid public debt leveraging, high inflation, or a very large net export advantage.

There are only ten cases since World War II in which both public and private debt deleveraged by 10 percentage points or more in a five-year period. Six of these were due to high inflation. Four of these were in large measure due to a high export surplus position, or more broadly speaking, a high current account surplus. One of these, Israel in 2003, comes the closest of any case I examined to deleveraging through growth, but even there, total debt outgrew GDP.

Deleveraging is difficult.

Absent the methods described above, if the total debt ratio were to be meaningfully reduced, either through an absolute decline in debt outstanding, or through a decline in the ratio, it would force significant, damaging downward pressure on GDP. The Great Depression saw such a deleveraging, and that’s why those years were so tremendously painful. By contrast, in the years after 2008, the U.S. government and the Federal Reserve acted to prevent deleveraging. We were saved from another Great Depression, but we were left with a massive pile of debt.

We are not at some ordinary moment in history. Instead, we are at an unprecedented, era-defining crossroads. Debt to GDP is the highest it has ever been in history. Politicians are unlikely to address this since it has proven easy to sidestep and the associated issues are highly difficult, so we will almost certainly continue down this debt path, increasingly burdened by high levels of private and public debt, ignoring what is in front of us, and wondering why global growth remains so mixed.

Part of our debt dilemma is that political leaders haven’t even squarely acknowledged the issue, let alone addressed the problem. But the more vexing part of our dilemma is that, as an examination of these past cases shows, deleveraging is a highly difficult proposition. It’s hard to expect any major economy to deleverage with only the tools of painful inflation, growth in other debt, or unrealistic trade account surpluses.

We need another tool in our deleveraging toolkit.

What About Restructuring?

The good news is that history suggests a fourth way. The process of elimination in the preceding paragraphs leads one to consider an obvious but largely overlooked way: private debt restructuring. It is the primary mechanism through which the absolute level of private debt can be reduced without directly and negatively affecting GDP. The easiest and most direct way to increase consumer spending (or demand) is to cut consumer debt. The easiest and most direct way to increase business investing is to cut business debt.

But it is a solution fraught with controversy.

Take the United States after the 2008 crisis. A rapid rise in mortgage debt was the proximate cause of the crisis—it rose from $5.3 trillion in 2001 to $10.6 trillion in 2007, an avalanche of new mortgage lending in the space of a mere six years. And yet even though we spent billions to bail out most of the lenders pursuant to this crisis (and largely without meaningful consequence to the management of those lending institutions), the amount of help provided to homeowners has been negligible in comparison. In the wake of the crisis, 15 million of 52 million mortgages in the United States were seriously underwater, with a loan-to-value ratio above 125 percent. When coupled with the diminished incomes of many of these households, their spending became highly constrained, leaving them far less able to buy new cars, take vacations, and make the many purchases that power an economy forward. If, during the crisis, we had provided meaningful, systemic relief to these mortgage-holders, the trajectory of our recovery would have been far stronger and our growth rates today would be far higher.

Here’s an example of a program that could have been employed in the 2008 to 2010 time period to address this issue—and could well be employed in the future. It would have been a one-time program whereby if a borrower, because of the collapse brought on by the crisis, had, for example, a $400,000 mortgage on a $300,000 house, the lender would be given a regulatory dispensation to write the mortgage down to, say, $250,000 and spread their loss over an extended period, perhaps 30 years. In exchange, the borrower would provide the lender a certificate that gives them half or more of the upside upon the sale of the house—a type of debt for equity swap.

That’s just one example of the type of program that could have been deployed, as relates to the U.S. mortgage-driven crisis of 2008. Other crises have primarily involved other types of loans—for example, commercial real estate in Japan in the 1990s—so they would require different types of programs. This type of debt restructuring approach has ample precedents, from England in the 1700s to the Latin American debt crisis in the 1980s, to “Jubilee,” the strategy in ancient civilizations whereby debts were forgiven. The imagination of policymakers would need to be guided by the facts of a given situation. The requirement would be that the program or programs be sufficiently broad to meaningfully address the full scope of the problem.

We have now unmistakably entered a new age of slow growth. The ongoing situation in Japan is as sobering as it is instructive. In the generation since its private debt eruption, its nominal GDP growth has been zero. During that time, it has fallen from 18 percent of the world’s GDP to only 6 percent, and still, its burden of private debt is both high and largely ignored.

Governments are working earnestly to revive global growth, but the tools they are looking to are inadequate for the task. They cannot simply continue their attempts to boost growth by constantly increasing our aggregate debt load. Instead, they need to deflate the dangers of private sector debt load in a way that does not undermine the economy. The most responsible course for that is the private debt restructuring that has been suggested here. Private debt restructuring by itself will dramatically boost demand—as much or more than any other policy or approach.

But leave this burden unaddressed, and the world will slowly suffocate.

I have a thought I have been kicking around in my head and it fits in perfectly with this article. I want to see what the expert NC commentariat has to say about it.

I can really only think of one way citizens will have any power over this government. But it would take a huge amount of organizing and it would only work if we had a huge group willing to participate, off the top of my head I’d say 1% of the population but would love someone with more knowledge to improve that. We can shut down the entire economy by refusing to pay debt.

If there were something really big, like #NoDAPL, A lame duck TPP vote, or another bank bail out that we really wanted to stop; if we could convince everyone to refuse to pay their bills starting on a specific day, I can’t imagine it taking more then a week for CEO’s to run around like chickens with their heads cut off. If someone has a better estimate of how long it would take to be noticed I would like to hear it.

We would need to pick one issue that is likely to happen and has a LOT of support among average people, more then any of the above issues currently have. We would need to put up a site and collect cell phone numbers to text and promise only to use them to announce the strike

If it were big enough to pick up media coverage it could blow up. It would have to start with one issue but if it was successful it could expand.

We could poll people from the first successful campaign and see if they were willing to repeat on the next issue and automatically opt them out if they don’t.

We could threaten a boycott of any institution that didn’t reverse late fees and credit score dings. So like I said if it was a big issue with at large public support and 1% willing to partake it could be the 21st century form of a union.

If it was something like TPP I bet the Unions would be on board to help orginize it.

Maybe union rank and filers might help organize, it seems union leaders I have read about are all against the TPP/TTIP/TiSA. But see: http://www.washingtonexaminer.com/not-exactly-the-99-top-union-leaders-salaries/article/2505719 Which DC restaurants and parties do they go to? Who do they golf with? What do they really believe?

And as the clearing process is controlled by the owners of debt, why wouldn’t they just help themselves to all the positive balances in our electronic dollar accounts? Didn’t that happen in Cyprus? “The government” and lots of private debt holders already have the “legal authority” to lien and garnish, often with the barest legal pretext, and bankruptcy is no kind of shield any more. Some anonymous benefactors might figure out how to blockade… but the temptations of joining the class of great wealth, or more likely becoming just another one of their villeins, or the fear of being crushed by the cyberwarfare infrastructure that we have all paid for (or our rulers have issued fiat money to pay for), set some unnatural limits on that hope too.

It bothers me that the prescription the authors have is “more groaf, increase GDP.” As if that will “fix” anything. And there’s the idiotic notion that “government” or other ruling bunches like “the Fed” and IMF give a sh!t about private debt other than to protect bondholders and mortgagees, http://realtytimes.com/consumeradvice/mortgageadvice1/item/23342-19990114_mtgevsmtgor, contained in this sentence: “The imagination of policymakers would need to be guided by the facts of a given situation.” As if “policymakers,” considering the realities of who now owns the “policymaking” apparatuses, would consider any such thing. Meantime, global human-induced climate change rumbles forward.

Unions work because they have focused power and they defend their members. There are alreay two million personal bankrutcies a year, I doubt a jump in collections and evictions would make a big difference to any decision makers. And once people end up homeless and destitute as a result, will your ’21 century union’ help them? If you do, you have a freerider problem.

Yoou are also playing your weakness. If you owe the banks millions, then you have leverage. People with the most reason to change this already are poor.

You treat not paying your bills like it was a retweet. It’s not. It is homelessnes, not eating, not having electricity, being a social outcast, losing your car, going to jail, losing your job.

Even if you win, you won’t be stronger as a result. You won’t have more money, more politicians in your pockets, laws to protect you. However, the bankers will respond and the next time will be harder.

You will also not shut down the economy. If you did, food would stop coming into stores, which means starvation in less than a week.

With so many people with so much debt (I can’t find numbers on what the average debtor pays per month though I am quite sure my just over $2K without a mortgage is in at least the 95th percentile, I imagine most pay at least a few hundred if you do include mortgages.) That has to add up to an eventual liquidity problem. The question is really what is that point and how many people would it take to get their?

Collective action always rouses a response. Though union labor power is at a low point currently, look at victories carved out by the Chicago teachers union or Verizon workers recently. The larger problem is to move people to collective action.

Much like a general nationwide strike. I’ve been wondering along similar lines too, lately.

” I can find ten interns who would pay ME to LET them do your job!” In the face of that general kind of threat, however worded; a general strike seems unlikely.

However, would a general spending slowdown have the same “slap them awake” effect, only slower and more insidiously? A general consumption strike? A general partial consumption strike?

It isn’t yet against the law to Just Stop Shopping or even just to Go Shopping Less.

That’s what I’ve been thinking about. They don’t need American labor. They need American consumption. They need online activity.

It seems to me if we could plan Days of Community, where people boycott all multinational companies — McDonalds and Walmart, but also Facebook and Google, and add in a social component where people gather in communal spaces to prod coverage while providing social camaraderie and offline networking, it could inflict damage while evading punishment for participation. Picnics in the park aren’t illegal, and you can’t force people to shop.

Nice idea, but I think a lot more than 1% of the population would need to participate. The-Powers-That-Be (TPTB) would hardly notice if 1% of debtors decided not to pay. That’s already happening now. The protestors would simply ruin their credit, and possibly lose their homes and cars.

http://www.acainternational.org/creditors-auto-and-credit-card-delinquencies-increase-in-first-quarter-39785.aspx

This web site shows that one to four unit home mortgages are at a delinquency rate of 4.66%, the lowest since 2006:

http://www.reuters.com/article/usa-mortgages-delinquencies-idUSL1N1AS127

The chart at this web site shows that multifamily mortgage delinquencies are at or below 0.5%, but that they have been much higher at times since 1996, and that didn’t prompt TPTB to make meaningful concessions to the 99%. Commercial mortgages are currently at about a 4% delinquency.

http://www.housingwire.com/articles/38007-multifamily-commercial-mortgage-delinquency-rates-near-20-year-lows

“Nice idea, but I think a lot more than 1% of the population would need to participate. The-Powers-That-Be (TPTB) would hardly notice if 1% of debtors decided not to pay. That’s already happening now. The protestors would simply ruin their credit, and possibly lose their homes and cars.”

Maybe yes — maybe no. Would depend on a number of factors: general circumstances, leadership, rank & file commitment, & most importantly, the ability to tie debt into problems generally in society/the economy, & “sell” a “solution” to the public. So ultimately, you are right: it would take more than a 1%.

Often I have thought of the exact same. But with so much of the 3 branches of government captured by the class holding the loans, the punishment would be legendary. Many good points made though, the best of which is the proposed equity swap on underwater mortgages after the ’08 collapse, a perfect missed opportunity to eliminate a world of hurt.

The private debt crisis is symptomatic of larger systemic problems of capitalism itself. The game changing crisis looming above all our heads are climate disruption, resource depletion, and corruption of social institutions. Relieving private debt will not address any of these important issues, in fact, will probably make them worse.

The deleveraging that needs to occur is from the overall system itself. The imagination needed to change course will not come form CEO’s and the current crop of political leaders. We are faced with creating a steady state economy and looking to capitalists to build that type of economy is a fools errand.

We need a new economy, not to revive the old one.

By all means we need to lower personal debt. But without a followup direction afterwards, the same mistakes will probably be repeated.

i’m noticing black markets stabilizing…it ain’t pretty but there’s nothing like herd desperation to kick off something beyond survival.

example: if ya watch this with an eye towards economics ya can’t miss it:

Black Market With Michael K.Williams | Lifted in London

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eLMhW6ysxY0

(i found Liverpool eye opening)

My dealer used to claim that cannabis prices are a coincident economic indicator.

With the legalization boom underway, even that industry is building a capacity bubble.

Ten years on, in Depression II, the USDA will be giving away government cannabis, the same way they used to hand out government cheese back in the Reagan era.

Ten years on, in Depression II, the USDA will be giving away government cannabis…and what will lord govs do about the munchies

:/

Buds ‘n cheese … the 21st century beer ‘n pretzels.

Bud is now America. Let them eat cheese…and drink America

agree with your points Norb but I only see change coming as a result of calamity.

Yes, sadly humans are much better at responding to ‘in the face’ crises than they are at anticipating the same. That is why Public Health, I.e.preventive medicine, gets a tiny fraction of the money that hospitals get.

And yes, we do need a new economy that works for the majority without growth- human population has more than doubled in the last 40 years and has resulted inthe extinction of over 30 percent of the species on the planet, not to mention climate change.

However, the financial problems looming as a result of kicking the debt can down the road pale to insignificance compared to the problems we face from decades, centuries even ,of kicking the ecological can down the road.

When push comes to shove finances, economies and even civilisations can be reinvented or rebuilt, but extinctions are forever. So whatever new economic system we end up with will have to be based on a less profligate exploitation of the Earths fundamental resources ,both the finite(mineral) and renewable(biological).

And get off this destructive addiction to growth, starting with human population growth which is increasingly threatening our life support system; it is the only one we have got.

‘We need a new economy, not to revive the old one.’

What you say is so evidently true, yet the entire apparatus of current public thought absolutely refuses to engage – it is just taken as given that we are more than smart enough to deal with any contingency when the actual history and results of what we’ve done is so deeply sobering, as in we absolutely do have it within us to destroy everything in an effort to keep on ‘growing’.

The really sad and depressing thing about much of this debt is that it also fueled a huge amount of material consumption. We’re also borrowing against the resources of the planet; that debt however can’t be written off.

The word “growth” is used 69 times in the article above; the word “climate”, zero times. Although at one point the author, a venture capitalist, does bemoan the fact that high debt levels in the richer nations will make it harder for them to buy up the natural resources of the poorer ones.

That is a rhetorical challenge. Historically, progressive change has been most possible in periods of “growth”. Growth in the era of melting ice caps and thawing permafrost methane belches signifies accelerating disaster to the environmentally conscious.

We need a term for improved organic/living conditions for normal people, this would include personal health and longevity, engagement, activity and security in a milieu independent of industrial goods production. If you substitute “wellbeing” for “growth” it might be possible envision a political economy wherein wellbeing improves as carbon foot prints and other industrial externalities decrease.

Attacking progressive positions on environmental grounds just reinforces the status quo by keeping ordinary people under unbearable economic stress, in turn making them view “environmentalism” as a threat.

It’s also interesting how no one ever seriously interrogates the Japan example. Yes, they have had near zero growth for some time now, but I can say from having lived there in this supposed period of stagnation, that they enjoy a remarkably high standard of living, due in no small part to a tightly controlled and sacrosanct public safety net. Even homeless people there have a sense of community and solidarity that, frankly, is quite remarkable. They also somehow manage not to execute people or keep them in prison for most of their natural lives. The country isn’t perfect by any means, but this sense of growth as not just an absolute good but a necessity needs to be reconsidered.

After all, what has China’s spectacular growth gotten them? Displacement of people from rural communities to smog blanketed cities. The AQI is 190 in Beijing right now. In Tokyo, it’s in the 30s, even lower where I lived near Nagoya. It’s 50 where I am now in Iowa City. Not to mention, China’s income/wealth inequality problem is just as bad as in the US, so all that miracle growth goes into the pockets of those who have no need for it.

In most developed countries, you could have zero growth and yield a massive improvement in the quality of life for the vast preponderance of people, simply by redistributing wealth. This would have a knock on effect of not further taxing the world’s natural resources as well.

I believe that Japan does in fact have the death penalty. Minor quibble in an otherwise excellent comment.

I actually didn’t know that, since I’d never heard of anyone being executed. That said, criminal justice is still an issue in Japan: defendants in practice have no real rights and regularly get railroaded on the thinnest of confessions. However, convicts don’t spend anywhere near as much time in jail.

The words we use to frame issues in this area are misleading For instance “…simply by redistributing wealth” could be more realistically stated as “…simply by redistributing real work.” That change begins to reveal the crux of the problem, which is that so many people do parasitic, negative-value work there isn’t enough “wealth” to go around.

student loans would seem a good place to start

“China’s unfolding crisis … won’t be small either, since China and other runaway lending countries that are economically intertwined with China such as Australia and South Korea together constitute more than a quarter of the world’s GDP.”

It will be devastating to the US (and Australian) higher education industry, which has become addicted to the budgetary meth of full-paying international students. Schools will fail – the only question is how high up the food chain it will reach.

Private higher education is in a very precarious place. Most low to mid tier schools are going to suffer from lower enrollment due to population and lack of funds.

Oh, NO ! Don’t tell me the Australian government might have to properly fund tertiary education like it did up until the late 80’s ? For sure, we’ll get another “debt & deficit” crisis….

Sounds like it’s time for a little seisachtheia.

That’s Greek.

Seems approximately equivalent to intifada.

…and where is Solon when we need him?!!

…and for that matter Cleisthenese – we could use a little redistricting to make the bubbles coagulate – put the scare into the rentier classes

Contrary to popular belief & theory, all debt matters; corporate, government, and household. The biggest difference is households do not have the financial engineering abilities that the other two have to ignore it.

https://fred.stlouisfed.org/graph/?g=3Y7i

PhilU’s suggestion seems to provide financial engineering ability to the household sector. While it does not deal with our worldwide runaway environmental debt, it could still be useful (e.g., motivating (1) mortgagors to offer debt-equity swaps; (2) governments to require same).

Steve Keen has been pointing this (i.e. that the precipitating factor is always PRIVATE debt levels) out for years….. he was one of the (many!!) economists who foresaw the 2008 crash.

By the way, one other claivoyant wasn`t even an economist but an anthropologist – Paul Jorion (see La Crise du Capitalisme Americain) – even foresaw which sector would be the scintilla…

Here’s a thought – What if the interest on private debt was switched from compound to simple? What effects would it have? Would be interested to know the more informed opinion of people here, including NC staff.

A lot of it is simple interest. All corporate bonds are simple interest.

Right. Thanks for that. What about household loans like mortgages, education, auto,etc? What would happen if they were converted to simple interest?

1. Please do your homework. Mortgages are not compound interest.

2. I don’t know why you are asking this question. The way interest charges are calculated is stipulated in the credit agreement with the borrower. That is not changing in any existing agreements. If someone were to pass laws restricting how interest was determined (and I don’t see how that happens, given that banks can offer any product nationwide, so you’d need to have all 50 states separately pass similar legislation), the banks would simply increase the nominal interest rate so as to compensate for any change in compounding.

“Instead, they need to deflate the dangers of private sector debt load in a way that does not undermine the economy.”

The problem is you want to deflate without endangering the economy, when you have inflated it to an extent that it is not possible.

“…a $400,000 mortgage on a $300,000 house, the lender would be given a regulatory dispensation to write the mortgage down to, say, $250,000 and spread their loss over an extended period, perhaps 30 years.”

The problem again is $300000 itself may be inflated figure. The right way to go about this would be look at a period before 1987, when the Fed started its mischief under Greenspan of reducing interest rates, flooding the system with money, and getting people into debt, and extrapolate based on the growth rate prior to that period and use that figure and not a figure (in the example, $250000) which itself might be a figure due to inflated asset prices. We would need a realistic reset.

“…public debt is $19 trillion.”

Public debt is just under $14T…https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/FYGFDPUN

The rest is debt the government ‘owes’ to itself.

In other words an accounting abstraction, like the SS trust fund.

“households do not have the financial engineering abilities that the other two have to ignore it”

Households can’t create dollars, nor can corporations. It would be counterfeiting if they did.

In what way does government debt matter for a sovereign like the US that only has debt in it’s own currency?

Imagine what it would be like without that ‘debt’. Zero net savings (all as bonds, i.e. money in savings accounts).

As it is nearly every dollar in existence is owed to the banking system. If we don’t continue issuing ‘debt’ (or directly creating dollars) we will end up in one of two places…collapse of the banking system or collapse of our pension funds. Or both.

“Everyone can create money. The problem is getting it accepted.” — Hyman Minsky

Banknotes in dollar denominations are the stock-in-trade of the financial sector. What’s missing is public banking (creating credit for the public realm).

“Banknotes in dollar denominations are the stock-in-trade of the financial sector.”

True, but banks aren’t allowed to create them for their own use. Only qualified(1) borrowers walking through their doors and taking out loans can increase the dollar supply through the banking system.

Banks can sell holdings in Treasuries/T-bills, but that doesn’t increase the money supply.

(1) OK that was a joke.

Every time you whip out a credit card and make a purchase, you create money. No one had that money before the transaction and suddenly loaned it to you. You spending the money doesn’t mean there is someone else somewhere else who is giving up the right to spend the money. That’s because it is not a loan to you out of some pool of loanable funds somewhere but is truly brand new money created just for you. You could argue that your bank created it for you, but that’s a distinction without a difference, as it was your decision and action that resulted in the money creation.

This whole scenario of course is why growth in private debt is so important: the money supply grows at the same time.

yes exactly right about money creation. Every dollar comes into existence simultaneously with the creation of some interest bearing debt claim, so money is just a proxy for that debt. The issue then is quite simple. The banks allowed way too much credit creation and to make matters worse they created much of it for consumption and speculation purposes creating inflation and inflated asset prices. Now there is more debt in the system than the real output and income of the economy can support. Debt used for productive purposes poses no such problems. Some day this will become more widely understood and the economists and central bankers of the era will be seen for the fools that they are. And to make matters worse their errors impoverished the vast bulk of the citizenry and created an entire class of oligarchs who got rich for no good reason.

“What greater indictment can be made of an economic theory than that it failed to forecast the greatest economic calamity in 70 years? Yet both schools of thought remain largely unchanged and unrepentant.”

=============================

I would add this article has increased my understanding of debt, its drawbacks and advantages, greatly. I am certainly going to forward it to friends.

Hear, hear, FD. One of the most important, original and insightful posts on NC (and thus, by extension, the internet) this year. Enormous.

Vague’s article parallels hedge fund honcho Ray Dalio’s pensées on deleveraging. Vague’s restructuring proposal roughly corresponds to Dalio’s “beautiful deleveraging” (which sounds like a Trumpian phrase, but Dalio coined it).

Unfortunately, under the American cultural principles of “pedal to the metal,” “no fear,” and “2 much ain’t enuff,” meaningful restructuring would simply enable a crack-up Bubble IV in the 2020s. (I’m counting on this — pimp my house, J-yel!)

Meanwhile, Planet Japan is the extreme outlier in Vague’s Chart 4. Reportedly, 40 percent of Japan’s single adults remain virgins. Apparently, even the instinct to reproduce withers in a no-hope, dead-in-the-water economy.

Being the most corporatist planet in the solar system, Japan won’t roll out any populist, “beautiful deleveraging” solutions. Indeed, with militarist backing from the USA, USA!, Japan might even decide to go out in a blaze of martial glory. That’s the postmodern nation-state’s ejection seat, when civilian economics fails. :-0

i do not even want to live thru the withdrawals from those dark pools

The author of the piece seems still stuck in the “loanable funds” mythology as well as the failure to distinguish between money issuer and money user. These are fatal flaws if the goal is to understand the fundamental problem of debt.

In a fiat money world where the major central banks maintain swap lines with each other, money creation is easier than it has ever been. (Strokes on a keyboard, as old Ben Bernanke says).

So, banks and other financial intermediaries (the shadow banks, e.g.) can expand their balance sheets ad infinitum, in theory. They always could do this, but the prior top of the money pyramid being gold made panics and collapse more likely.

Today’s top of the pyramid money is electricity manipulated by central banks to appear as numbers on various screens. And, to paraphrase Jamie Galbraith, we are not likely to experience a shortage of electricity any time soon.

So, the potential for the ponzi phase of the Minsky cycle to get extended beyond what has been seen in the past is quite large. All it takes is a willingness to roll over existing debt in “extend and pretend” mode. And central banks, especially the bank of japan and the ecb, seem only too willing to jump in and buy financial instruments regardless of true underlying “value.”

It’s only when some human actors in the system stop believing in the connection between the numbers on the screens their looking at and the “value” of the stuff they get in exchange for those numbers does the roller coaster hit the top of the hill and start down. And because it’s unpredictable, sometimes irrational human beings who are making that judgment about the relationship of price to value, no one can predict precisely how much debt is too much debt.

IMNSHO, therefore, Steve Keen, the author of this post and any one else who tries to come up with a “tipping point” for when debt becomes too much debt, either in relative or absolute terms, are doomed to failure.

So the future’s so bright, we gotta wear shades?

Now I realize that Ken Rogoff just made up all that crap about sovereign defaults.

It never happened. Because it can’t happen. ;-)

Not sure I understand the comment.

It’s sarcasm, in response to “no shortage of electricity [to create screen “money”] and “banks expanding their balance sheets ad infinitum, in theory.”

In practice, no. Private banks that overexpand suffer liquidity crises and fail. Central banks that overexpand see their currencies collapse, followed by critical imports collapsing.

Infinite credit expansion creates crises, rather than resolving them.

My point is that the definition of “overexpansion” is not one derived from laws of nature, but from the vagaries of human judgment.

So, despite the desire to set a particular debt ratio as “the” one beyond which lies disaster, there is no such definite point.

A good example lies in the (over?)expansion of the Federal Reserve, the ECB and the Bank of Japan, the last of which has been (over)expanding for over twenty years.

How many trillions of dollars/euros/yen need to be added to the balance sheets of these central banks before the collapse of their currencies?

My position is that there is no fixed point because

a) the electrical system does not impose a constraint on their ability to create money, and

b) there is no agreement on how much is too much.

yes there is no definitive point, but how long can this go on. Monetary systems have been failing for as long as humans have been creating them. This current era of fiat money to will end. It seems to be in its death throws but how and when is hard to predict.

Tell this to geeks, portugeese and spanicks, for instance. They will belieeeeeeeeeve.

(FWIW: i am Spanick, not contempt intended)

The point I’m making is that the factors which determine when a financial crisis occurs are not “laws” like the laws of physics, which you can use to predict things like planetary movement. Instead, they are human rules subject to use and abuse. And when actors in the system with enough power perceive that “the end is near,” and panic, then the system crashes. How badly and who gets hurt are also determined by power relations, as the Spaniards, among others, have discovered. Y a pesar de no soy un Español, sí leo los periódicos españoles de vez en cuanto. :)

You are right to point out that is is quite literally a Ponzi scheme. The central banks have gone full Ponzi mode and for now it is working, but at some point people will wake up. For now it is just to shocking to consider for most of us.

the loanable funds theory of money and banking is JOKE, but one that most people don’t understand.

Consumer debt has just barely reached a level above the 2007-2008 high. Most new debt these days is corporate debt, much of it buying back it’s own shares to prop up profit numbers, and investment in fracking, which has now subsided (dropped off a cliff).

https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/CMDEBT

Debt. Can’t live without it; can’t live with it.

Yes, debt matters.

As Michael Pettis wrote

But even if this is all there were to debt – and in fact in my classes at both Peking University and, previously, at Columbia University I propose to my students that one way to think of the liability side of the balance sheet is precisely as a series of formulae that distribute the operating earnings of a company (or the total production of goods and services of a country) – this would still make it singularly important in understanding the functioning of and prospects for an economy. After all the way you distribute earnings is a major part of an institution’s incentive structure, and changes in the structure of incentives lead almost automatically to changes in the ways economic agents behave.

And inequality too.

Now debt is not only high, but used to distribute earnings in ways that increase inequality, as Vague writes. Too much debt, wrong incentive structure… nice future.

Not sure how that equates to today’s reality of off-balance sheet accounting????

This article with the thoughts of Macquarie Group’s global strategist, Viktor Shvets, dovetails nicely with this post:

http://www.theepochtimes.com/n3/2143386-viktor-shvets-the-private-sector-will-never-recover/

This is a very good article that gets to some very major issues. Unfortuanltey it comes after the fact. How and why was this allowed to happen? On average credit should never grow at a rate that exceeds the growth on the real economy. Furthermore credit should be extended primarily for productive purposes and not consumption and speculation.

This explosion of debt can all be traced directly back to the closing the of the gold window in 1971. Prior to that period the U.S. economy had never experienced any meaningful inflation whatsoever, which can be seen in any chart of CPI back to the early 1900s. Inflation only appears after 1971. In addition debt and real GDP grew in tandem until 1971 at which time they begin to diverge radically.

Following is a link to a long essay that explains these ideas in much greater detail. It has been read by some of the world’s most prominent investors and widely circulated.

https://medium.com/@Robert_NYC/monetary-madness-438836c44464#.qy6com5dt

Richard Werner’s Book; The Princes of the Yen is an excellent exopose of Japan’s credit crisis and contains one of the best descriptions of how modern banking systems really operate. The current debt global debt crisis was made possible and inevitable once they killed the Bretton Woods gold exchange standard.

This is a major historical monetary disaster which is still in the process of playing itself out. Money is what mediates almost all forms of human interaction and when the monetary system goes bad it has profound social and economic implications.

The monetary system must be reformed and it will be at some point. We can only hope that is not precipiated by an immense economic dislocation.

It was in 1945 that US government debt first became more than half the Fed’s balance sheet, and gold less than half:

The CPI proceeded to more than double from 1945 to 1971, when Nixon was obliged to pull the plug on gold redemptions that the US could no longer honor.

Not contradicting your thesis, but rather asserting that the postwar interlude of the dollar-centric Bretton Woods standard afforded the US a quarter-century time lag before the inflationism initiated in the 1940s finally took its toll.

yes Jim, CPI did kick up between 1945 and 1971, as compared to pre 1945, but was still very modest Not sure it doubled without looking at the data but it was close. It really accelerated after 1971.

In any case it would make sense that it would accelerate somewhat after 1945 since dollars became the official reserve currency which facilitated trade, current account and budget deficits. The U.S. was nevertheless still relatively prudent in terms of fiscal and monetary policy during that time frame. It all went Paul Tong after 1971 though. sorry for the British colloquialism.

“…inflation…”

If an hour of labor will still buy more in real terms than it would in 1945, or 1970, or…

…why does inflation matter?

Why does shoplifting matter?

The system survives. But the costs of dishonesty are imposed on the honest ones.

“Why does shoplifting matter?”

Inflation is hardly analogous to shoplifting, that’s a strawman. Inflation is a natural consequence of a growing system. The problem is rising inequality, not rising inflation. Inflation is at all-time lows…how’s that working out for us?

“…the costs of dishonesty are imposed on the honest ones”

Not necessarily. Inflation reduces our private debt burden. Since we have so much private debt, that’s a big deal. The cost burden goes to the banking system, although, in all fairness, banks make most of their money on closing costs. Just say no.

Our savings grow (if we have any, if we don’t it doesn’t matter). Either way we maintain parity with the price level (again excepting the increasing inequality situation, in which inflation is disproportionately borne by the 90%).

Inflation is very analogous to shoplifting, and inflation is NOT a natural consequence of a growing system as you seem to believe. Just look at the data of CPI and real growth from 1913 to 1971, then look at it from 1971 to the present. The earlier period had high growth and virtually no inflation. The latter period, lower growth and higher inflation. So you are completely wrong on this point. The reason? After 1971 the banking system produced excess credit/money because there was no longer any thing anchoring the monetary system. As for inflation it is exactly like shoplifting as As Keynes explained in the Economic Consequences of the Peace.

“By a continuing process of inflation, governments can confiscate, secretly and unobserved, an important part of the wealth of their citizens. By this method, they not only confiscate, but they confiscate arbitrarily; and, while the process impoverishes many, it actually enriches some. The sight of this arbitrary rearrangement of riches strikes not only at security, but at confidence in the equity of the existing distribution of wealth. Those to whom the system brings windfalls . . . become ‘profiteers’, who are the object of the hatred of the bourgeoisie, whom the inflationism has impoverished not less than the proletariat. As the inflation proceeds . . . all permanent relations between debtors and creditors, which form the ultimate foundation of capitalism, become so utterly disordered as to be almost meaningless.

There is no subtler, nor surer means of overturning the existing basis of society that to debauch the currency. The process engages all the hidden forces of economic law on the side of destruction, and does it in a manner which not one man in a million is able to diagnose.”

And you correctly point out that inflation is disproportionally borne by the 90%.

Amen

How big is the cost of shoplifting, compared to the looting by banksters and other kleptocrats and corruption and fraud and the rest, and of course the ded-end war machine? Speaking of honest ones. With further query, “how many of the rest of us are honest, and careful about eating our own externalities?”

Species death wish seems pretty apparent. Gaia has about had it with us apes.

Propaganda, nonsense think and reality.

Propoganda

Economic liberalism looks to undermine Government at every opportunity

It gets its main stream media supporters to stoke up fears about Government debt.

It ignores the private debt, because it doesn’t want you to look at that problem.

Governments can directly monetise their debt through the Central Bank and so we are all pushed into looking in the wrong direction.

Nonsense think

Neoclassical economics was rolled out globally for mainstream economics leading to nonsense think on debt.

Its flawed assumptions on money and debt leave everyone blind to its problems with people assuming that one persons saving is lent out to other people.

This flawed assumption leads to a flawed conclusion; debt cannot cause a problem as money is just being transferred from one person to another.

This is not true, but Central Bank and IMF models totally ignore money and debt as they are neoclassical economists. This is why their forecasts always show recovery is coming, they are missing the problem.

2008 – “How did that happen?” – they don’t know because their models don’t include the problem.

2005 – Steve Keen sees the private debt bubble inflating and issues warnings.

2007 – Ben Bernanke sees no problems ahead.

Post 2008, Central Bankers try and use more debt to solve a debt problem.

They haven’t got a clue.

Dear Sound Of The Suburbs,

You mentioned that:

“Neoclassical economics was rolled out globally for mainstream economics leading to nonsense think on debt.

Its flawed assumptions on money and debt leave everyone blind to its problems with people assuming that one persons saving is lent out to other people.

This flawed assumption leads to a flawed conclusion; debt cannot cause a problem as money is just being transferred from one person to another.

This is not true, but Central Bank and IMF models totally ignore money and debt as they are neoclassical economists. This is why their forecasts always show recovery is coming, they are missing the problem.”

In your opinion, what will be the solution to the shortcomings of neoclassical economics? Also, why is the assumption “one person’s savings is lent out to other people” flawed?

Sincerely,

a student of economics =D

While it’s true that debt is tied with growth and too much debt — not sure how to define too much although we seem close — weighs upon growth — the debt to GDP ratio Vague focuses on seems more like an indicator for underlying problems than a root cause for problems.

If every debt were a loan for increasing production — with a time lag perhaps — and demand always absorbed additional production without depressing prices then increasing debt would increase GDP so that the debt to GDP figure would ride at some nominal level reflecting the ratio between debt and the resulting future increase in production. Of course all debt does not serve to increase production and demand can seldom absorb the capacity to produce made possible by our energy driven machinery and increased production usually impacts price as it outruns demand. Vague asserts debt is necessary for growth. Assuming it is — the debt to GDP ratio serves as a measure for how effective debt is at building growth. A high ratio of debt to GDP indicates debt isn’t as effective at building growth as a lower ratio of debt to GDP. Past instances of high ratios of debt to GDP coincided with a series of financial and economic crises. I think this suggests a high ratio of debt to GDP indicates some underlying problems in an economy beyond just indicating an economy less efficient at using debt to achieve growth.

Instead of looking too hard at the ratio of debt to GDP I think it might be better to look for the problems in some of the details behind the creation and distribution of debt. The “rules” for debt creation and distribution change and changed radically prior to our most recent economic collapse.

Looking at the features of an economy with a relatively high ratio of debt to GDP like the American economy several problems become evident. An economy with high levels of inequality and maldistribution of incomes — like our American economy — would tend to have problems of declining aggregate demand. One person can only consume a finite amount of real goods and services. Even trying hard the wealthy cannot spend all their income buying goods and services. The other 99.99% of the people have trouble making their income fit their demand needs and desires. Our banks are happy to offer debt to the 99.99% in return for high interest payments. Buy today and pay and pay tomorrow. Without this debt today consumer demand today would fall short but tomorrow demand will sag even more than before — without creating new debt.

Our Corporations and financial institutions have been given access to a huge influx of debt money tossed on top of their increased monopoly rents and their tendency to retain profits for purposes other than investment in their core business. This inflood of debt serves to leverage the future earnings of our monopolies facilitating their wholesale looting by their high level “management”. Nothing is done about monopoly creation or the monopoly money wars to build the largest possible cartels. Nothing is done to stop the looting of what remains of our Industry.

I think there are more underlying problems but that should be sufficient to argue that while a high ratio of debt to GDP seems an excellent indicator of grave problems in an economy that ratio in itself doesn’t serve as a root cause. Fixing the problems debt itself creates will involve the kinds of fixes Vague argues for. Fixing the root causes of problems in the American economy will require much more than fixing the problems of debt. Other economies have their own root causes for problems and will require other fixes.

But given Peak Oil and other resource peaks and Global Warming and loose nuclear cannons we may be facing much more serious and difficult problems than the mere collapse of our economies.

Chart #3 tells the whole story for me. Our author doesn’t really point this out.

Look at the line for France…1790…the French installed this amazing last resort debt write off machine in the Place de la Concorde and it seems to have been most effective. Jubilee. All the imbalances restored and those who have been forced to the periphery by debt serfdom can return to the center.

There was no doubt a bit of collateral damage.

This is what I try to explain to my rich conservative bootstrapper and neo liberal acquaintances.

You can have it one way or the other…your choice.

The Jubilee can come agreeably and willingly with planning as those old kings of Babylon knew or it can come with a lot of wailing and lamentation. War, Chaos and Violent Revolution: The Four Horsemen are always ready and willing for a quick write down and deleveraging. They love to take care of the creditor and the debtor. Just ask the ones in Aleppo right now.

Extending terms of debts owed by persons or corporate persons is already happening all over the place, but there is a great deal of drag in the system that has prevented those workers or companies from being able to utilize the time bought to improve their positions. The precarious balance of China has in good measure been maintained by multiple relaxations of terms of debt payments. What happens when debt terms go to 60 years only ten years from now?