This is Naked Capitalism fundraising week. 1325 donors have already invested in our efforts to combat corruption and predatory conduct, particularly in financial realm. Please join us and participate via our Tip Jar, which shows how to give via check, credit card, debit card, or PayPal. Read about why we’re doing this fundraiser, what we’ve accomplished in the last year, and our fifth goal, more original reporting.

Yves here. We are delighted to feature an excerpt from Dean Baker’s new book Rigged, which you can find at http://deanbaker.net/books/rigged.htm via either a free download or in hard copy for the cost of printing and shipping. The book argues that policy in five areas, macroeconomics, the financial sector, intellectual property, corporate governance, and protection for highly paid professionals, have all led to the upward distribution of income. The implication is that the yawning gap between the 0.1% and the 1% versus everyone else is not the result of virtue (“meritocracy”) but preferential treatment, and inequality would be substantially reduced if these policies were reversed.

I urge you to read his book in full and encourage your friends, colleagues, and family to do so as well.

By Dean Baker, Co-Director, Center for Economic and Policy Research

Chapter 1: Introduction: Trading in myths

In winter 2016, near the peak of Bernie Sanders’ bid for the Democratic presidential nomination, a new line became popular among the nation’s policy elite: Bernie Sanders is the enemy of the world’s poor. Their argument was that Sanders, by pushing trade policies to help U.S. workers, specifically manufacturing workers, risked undermining the well-being of the world’s poor because exporting manufactured goods to the United States and other wealthy countries is their path out of poverty. The role model was China, which by exporting has largely eliminated extreme poverty and drastically reduced poverty among its population. Sanders and his supporters would block the rest of the developing world from following the same course.

This line, in its Sanders-bashing permutation, appeared early on in Vox, the millennial-oriented media upstart, and was quickly picked up elsewhere (Beauchamp 2016).[1] After all, it was pretty irresistible. The ally of the downtrodden and enemy of the rich was pushing policies that would condemn much of the world to poverty.

The story made a nice contribution to preserving the status quo, but it was less valuable if you respect honesty in public debate.

The problem in the logic of this argument should be apparent to anyone who has taken an introductory economics course. It assumes that the basic problem of manufacturing workers in the developing world is the need for someone who will buy their stuff. If people in the United States don’t buy it, then the workers will be out on the street and growth in the developing world will grind to a halt.

In this story, the problem is that we don’t have enough people in the world to buy stuff. In other words, there is a shortage of demand. But is it really true that no one else in the world would buy the stuff produced by manufacturing workers in the developing world if they couldn’t sell it to consumers in the United States? Suppose people in the developing world bought the stuff they produced raising their living standards by raising their own consumption.

That is how the economics is supposed to work. In the standard theory, general shortages of demand are not a problem.[2] Economists have traditionally assumed that economies tended toward full employment. The basic economic constraint was a lack of supply. The problem was that we couldn’t produce enough goods and services, not that we were producing too much and couldn’t find anyone to buy them. In fact, this is why all the standard models used to analyze trade agreements like the Trans-Pacific Partnership assume trade doesn’t affect total employment.[3] Economies adjust so that shortages of demand are not a problem.

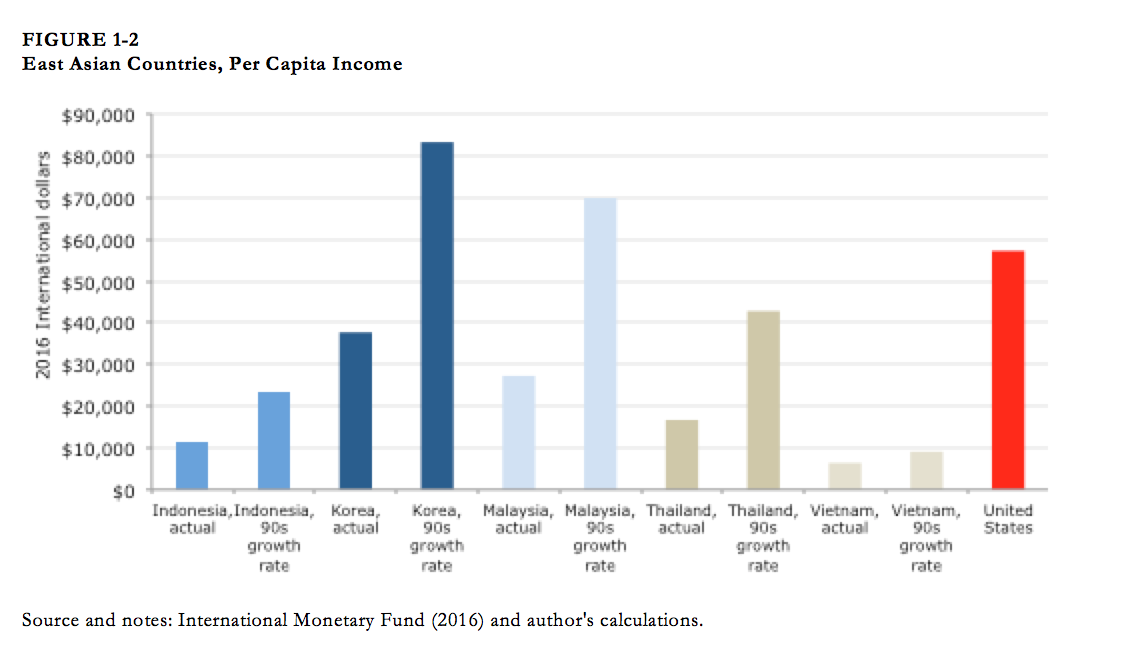

In this standard story (and the Sanders critics are people who care about textbook economics), capital flows from slow-growing rich countries, where it is relatively plentiful and so gets a low rate of return, to fast-growing poor countries, where it is scarce and gets a high rate of return (Figure 1-1).

So the United States, Japan, and the European Union should be running large trade surpluses, which is what an outflow of capital means. Rich countries like ours should be lending money to developing countries, providing them with the means to build up their capital stock and infrastructure while they use their own resources to meet their people’s basic needs.

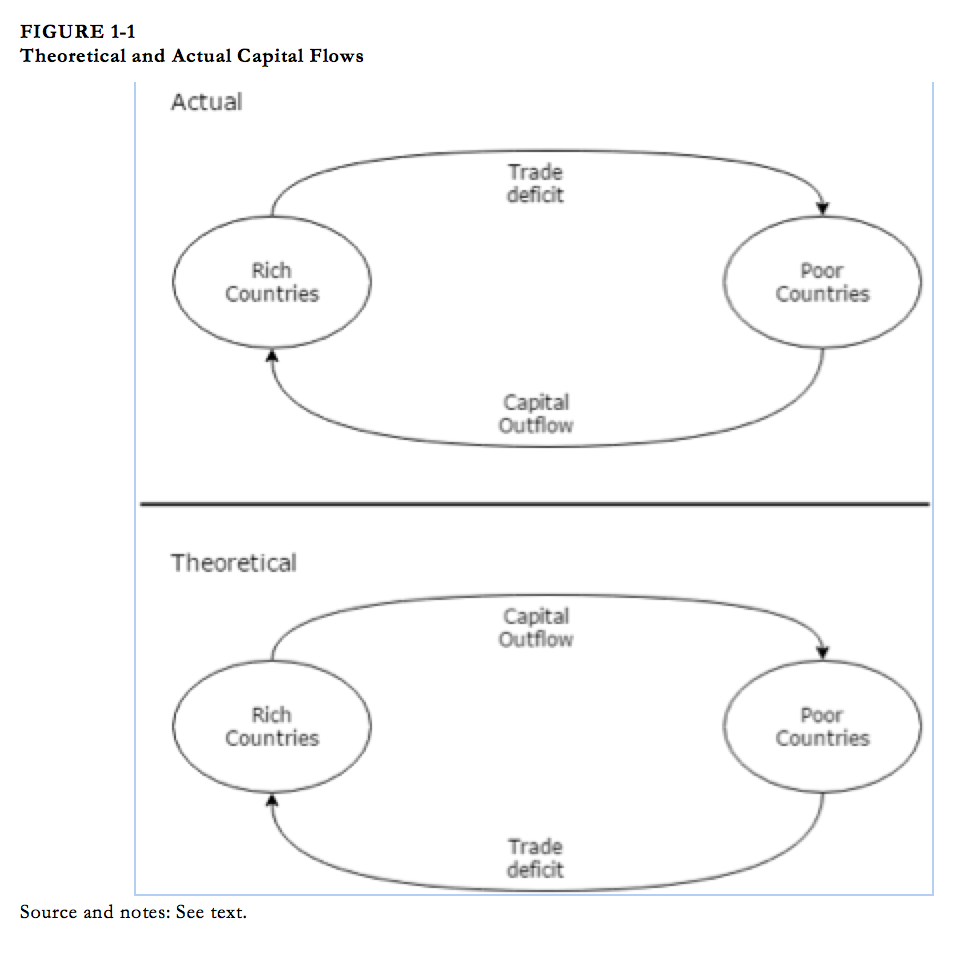

This wasn’t just theory. That story accurately described much of the developing world, especially Asia, through the 1990s. Countries like Indonesia and Malaysia were experiencing rapid annual growth of 7.8 percent and 9.6 percent, respectively, even as they ran large trade deficits, just over 2 percent of GDP each year in Indonesia and almost 5 percent in Malaysia.

These trade deficits probably were excessive, and a crisis of confidence hit East Asia and much of the developing world in the summer of 1997. The inflow of capital from rich countries slowed or reversed, making it impossible for the developing countries to sustain the fixed exchange rates most had at the time. One after another, they were forced to abandon their fixed exchange rates and turn to the International Monetary Fund (IMF) for help.

Rather than promulgating policies that would allow developing countries to continue the textbook development path of growth driven by importing capital and running trade deficits, the IMF made debt repayment a top priority. The bailout, under the direction of the Clinton administration Treasury Department, required developing countries to switch to large trade surpluses (Radelet and Sachs 2000, O’Neil 1999).

The countries of East Asia would be far richer today had they been allowed to continue on the growth path of the early and mid-1990s, when they had large trade deficits (Figure 1-2). Four of the five would be more than twice as rich, and the fifth, Vietnam, would be almost 50 percent richer. South Korea and Malaysia would have higher per capita incomes today than the United States.

In the wake of the East Asia bailout, countries throughout the developing world decided they had to build up reserves of foreign exchange, primarily dollars, in order to avoid ever facing the same harsh bailout terms as the countries of East Asia. Building up reserves meant running large trade surpluses, and it is no coincidence that the U.S. trade deficit has exploded, rising from just over 1 percent of GDP in 1996 to almost 6 percent in 2005. The rise has coincided with the loss of more than 3 million manufacturing jobs, roughly 20 percent of employment in the sector.

There was no reason the textbook growth pattern of the 1990s could not have continued. It wasn’t the laws of economics that forced developing countries to take a different path, it was the failed bailout and the international financial system. It would seem that the enemy of the world’s poor is not Bernie Sanders but rather the engineers of our current globalization policies.

There is a further point in this story that is generally missed: it is not only the volume of trade flows that is determined by policy, but also the content. A major push in recent trade deals has been to require stronger and longer patent and copyright protection. Paying the fees imposed by these terms, especially for prescription drugs, is a huge burden on the developing world. Bill Clinton would have much less need to fly around the world for the Clinton Foundation had he not inserted the TRIPS (Trade Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights ) provisions in the World Trade Organization (WTO) that require developing countries to adopt U.S.-style patent protections. Generic drugs are almost always cheap —patent protection makes drugs expensive. The cancer and hepatitis drugs that sell for tens or hundreds of thousands of dollars a year would sell for a few hundred dollars in a free market. Cheap drugs would be more widely available had the developed world not forced TRIPS on the developing world.

Of course, we have to pay for the research to develop new drugs or any innovation. We also have to compensate creative workers who produce music, movies, and books. But there are efficient alternatives to patents and copyrights, and the efforts by the elites in the United States and other wealthy countries to impose these relics on the developing world is just a mechanism for redistributing income from the world’s poor to Pfizer, Microsoft, and Disney. Stronger and longer patent and copyright protection is not a necessary feature of a 21st century economy.

In textbook trade theory, if a country has a larger trade surplus on payments for royalties and patent licensing fees, it will have a larger trade deficit in manufactured goods and other areas. The reason is that, in theory, the trade balance is fixed by national savings and investment, not by the ability of a country to export in a particular area. If the trade deficit is effectively fixed by these macroeconomic factors, then more exports in one area mean fewer exports in other areas. Put another way, income gains for Pfizer and Disney translate into lost jobs for workers in the steel and auto industries.

The conventional story is that we lose manufacturing jobs to developing countries because they have hundreds of millions of people willing to do factory work at a fraction of the pay of manufacturing workers in the United States. This is true, but developing countries also have tens of millions of smart and ambitious people willing to work as doctors and lawyers in the United States at a fraction of the pay of the ones we have now.

Gains from trade work the same with doctors and lawyers as they do with textiles and steel. Our consumers would save hundreds of billions a year if we could hire professionals from developing countries and pay them salaries that are substantially less than what we pay our professionals now. The reason we import manufactured goods and not doctors is that we have designed the rules of trade that way. We deliberately write trade pacts to make it as easy as possible for U.S. companies to set up manufacturing operations abroad and ship the products back to the United States, but we have done little or nothing to remove the obstacles that professionals from other countries face in trying to work in the United States. The reason is simple: doctors and lawyers have more political power than autoworkers.[4]

In short, there is no truth to the story that the job loss and wage stagnation faced by manufacturing workers in the United States and other wealthy countries was a necessary price for reducing poverty in the developing world.[5] This is a fiction that is used to justify the upward redistribution of income in rich countries. After all, it is pretty selfish for rich country autoworkers and textile workers to begrudge hungry people in Africa and Asia and the means to secure food, clothing, and shelter.

The other aspect of this story that deserves mention is the nature of the jobs to which our supposedly selfish workers feel entitled. The manufacturing jobs that are being lost to the developing world pay in the range of $15 to $30 an hour, with the vast majority closer to the bottom figure than the top. The average hourly wage for production and nonsupervisory workers in manufacturing in 2015 was just under $20 an hour, or about $40,000 a year. While a person earning $40,000 is doing much better than a subsistence farmer in Sub-Saharan Africa, it is difficult to see this worker as especially privileged.

By contrast, many of the people remarking on the narrow-mindedness and sense of entitlement of manufacturing workers earn comfortable six-figure salaries. Senior writers and editors at network news shows or at the New York Times and Washington Post feel entitled to their pay because they feel they have the education and skills to be successful in a rapidly changing global economy.

These are the sort of people who consider it a sacrifice to work at a high-level government job for $150,000 to $200,000 a year. For example, Timothy Geithner, President Obama’s first treasury secretary, often boasts about his choice to work for various government agencies rather than earn big bucks in the private sector. His sacrifice included a stint as president of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York that paid $415,000 a year.[6] This level of pay put Geithner well into the top 1 percent of wage earners.

Geithner’s comments about his sacrifices in public service did not elicit any outcry from the media at the time because his perspective was widely shared. The implicit assumption is that the sort of person who is working at a high level government job could easily be earning a paycheck that is many times higher if they were employed elsewhere. In fact, this is often true. When he left his job as Treasury Secretary, Geithner took a position with a private equity company where his salary is likely several million dollars a year.

Not everyone who was complaining about entitled manufacturing workers was earning as much as Timothy Geithner, but it is a safe bet that the average critic was earning far more than the average manufacturing worker — and certainly far more than the average displaced manufacturing worker.

Turning the Debate Right-Side Up: Markets Are Structured

The perverse nature of the debate over a trade policy that would have the audacity to benefit workers in rich countries is a great example of how we accept as givens not just markets themselves but also the policies that structure markets. If we accept it as a fact of nature that poor countries cannot borrow from rich countries to finance their development, and that they can only export manufactured goods, then their growth will depend on displacing manufacturing workers in the United States and other rich countries.

It is absurd to narrow the policy choices in this way, yet the centrists and conservatives who support the upward redistribution of the last four decades have been extremely successful in doing just that, and progressives have largely let them set the terms of the debate.

Markets are never just given. Neither God nor nature hands us a worked-out set of rules determining the way property relations are defined, contracts are enforced, or macroeconomic policy is implemented. These matters are determined by policy choices. The elites have written these rules to redistribute income upward. Needless to say, they are not eager to have the rules rewritten which means they have no interest in even having them discussed.

But for progressive change to succeed, these rules must be addressed. While modest tweaks to tax and transfer policies can ameliorate the harm done by a regressive market structure, their effect will be limited. The complaint of conservatives — that tampering with market outcomes leads to inefficiencies and unintended outcomes — is largely correct, even if they may exaggerate the size of the distortions from policy interventions. Rather than tinker with badly designed rules, it is far more important to rewrite the rules so that markets lead to progressive and productive outcomes in which the benefits of economic growth and improving technology are broadly shared

This book examines five broad areas where the rules now in place tend to redistribute income upward and where alternative rules can lead to more equitable outcomes and a more efficient market:

- Macroeconomic policies determining levels of employment and output.

- Financial regulation and the structure of financial markets.

- Patent and copyright monopolies and alternative mechanisms for financing innovation and creative work.

- Pay of chief executive officers (CEOs) and corporate governance structures.

- Protections for highly paid professionals, such as doctors and lawyers.

In each of these areas, it is possible to identify policy choices that have engineered the upward redistribution of the last four decades.

In the case of macroeconomic policy, the United States and other wealthy countries have explicitly adopted policies that focus on maintaining low rates of inflation. Central banks are quick to raise interest rates at the first sign of rising inflation and sometimes even before. Higher interest rates slow inflation by reducing demand, thereby reducing job growth, and reduced job growth weakens workers’ bargaining power and puts downward pressure on wages. In other words, the commitment to an anti-inflation policy is a commitment by the government, acting through central banks, to keep wages down. It should not be surprising that this policy has the effect of redistributing income upward.

The changing structure of financial regulation and financial markets has also been an important factor in redistributing income upward. This is a case where an industry has undergone very rapid change as a result of technological innovation. Information technology has hugely reduced the cost of financial transactions and allowed for the development of an array of derivative instruments that would have been unimaginable four decades ago. Rather than modernizing regulation to ensure that these technologies allow the financial sector to better serve the productive economy, the United States and other countries have largely structured regulations to allow a tiny group of bankers and hedge fund and private equity fund managers to become incredibly rich.

This changed structure of regulation over the last four decades was not “deregulation,” as is often claimed. Almost no proponent of deregulation argued against the bailouts that saved Wall Street in the financial crisis or against the elimination of government deposit insurance that is an essential part of a stable banking system. Rather, they advocated a system in which the rules restricting their ability to profit were eliminated, while the insurance provided by the Federal Reserve Board, the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, and other arms of the government were left in place. The position of “deregulators” effectively amounted to arguing that they should not have to pay for the insurance they were receiving.

The third area in which the rules have been written to ensure an upward redistribution is patent and copyright protection. Over the last four decades these protections have been made stronger and longer. In the case of both patent and copyright, the duration of the monopoly period has been extended. In addition, these monopolies have been applied to new areas. Patents can now be applied to life forms, business methods, and software. Copyrights have been extended to cover digitally produced material as well as the internet. Penalties for infringement have been increased and the United States has vigorously pursued their application in other countries through trade agreements and diplomatic pressure.

Government-granted monopolies are not facts of nature, and there are alternative mechanisms for financing innovation and creative work. Direct government funding, as opposed to government granted monopolies, is one obvious alternative. For example, the government spends more than $30 billion a year on biomedical research through the National Institutes of Health — money that all parties agree is very well spent. There are also other possible mechanisms. It is likely that these alternatives are more efficient than the current patent and copyright system, in large part because they would be more market-oriented. And, they would likely lead to less upward redistribution than the current system.

The CEOs who are paid tens of millions a year would like the public to think that the market is simply compensating them for their extraordinary skills. A more realistic story is that a broken corporate governance process gives corporate boards of directors — the people who largely determine CEO pay —little incentive to hold down pay. Directors are more closely tied to top management than to the shareholders they are supposed to represent, and their positions are lucrative, usually paying six figures for very part-time work. Directors are almost never voted out by shareholders for their lack of attention to the job or for incompetence.

The market discipline that holds down the pay of ordinary workers does not apply to CEOs, since their friends determine their pay. And a director has little incentive to pick a fight with fellow directors or top management by asking a simple question like, “Can we get a CEO just as good for half the pay?” This privilege matters not just for CEOs; it has the spillover effect of raising the pay of other top managers in the corporate sector and putting upward pressure on the salaries of top management in universities, hospitals, private charities, and other nonprofits.

Reformed corporate governance structures could empower shareholders to contain the pay of their top-level employees. Suppose directors could count on boosts in their own pay if they cut the pay of top management without hurting profitability, With this sort of policy change, CEOs and top management might start to experience some of the downward wage pressure that existing policies have made routine for typical workers.

This is very much not a story of the natural workings of the market. Corporations are a legal entity created by the government, which also sets the rules of corporate governance. Current law includes a lengthy set of restrictions on corporate governance practices. It is easy to envision rules which would make it less likely that CEOs earn such outlandish paychecks by making it easier for shareholders to curb excessive pay.

Finally, government policies strongly promote the upward redistribution of income for highly paid professionals by protecting them from competition. To protect physicians and specialists, we restrict the ability of nurse practitioners or physician assistants to perform tasks for which they are entirely competent. We require lawyers for work that paralegals are capable of completing. While trade agreements go far to remove any obstacle that might protect an autoworker in the United States from competition with a low-paid factory worker in Mexico or China, they do little or nothing to reduce the barriers that protect doctors, dentists, and lawyers from the same sort of competition. To practice medicine in the United States, it is still necessary to complete a residency program here, as though there were no other way for a person to become a competent doctor.

We also have done little to foster medical travel. This could lead to enormous benefits to patients and the economy, since many high cost medical procedures can be performed at a fifth or even one-tenth the U.S. price in top quality medical facilities elsewhere in the world. In this context, it is not surprising that the median pay of physicians is over $250,000 a year and some areas of specialization earn close to twice this amount. In the case of physicians alone, if pay were reduced to West European-levels the savings would be close to $100 billion a year (@ 0.6 percent of GDP).

Changing the rules in these five areas could reduce much and possibly all of the upward redistribution of the last four decades. But changing the rules does not mean using government intervention to curb the market. It means restructuring the market to produce different outcomes. The purpose of this book is to show how.

[1] See also Weissman (2016), Iacono (2016), Worstall (2016), Lane (2016), and Zakaria (2016).

[2] As explained in the next chapter, this view is not exactly correct, but it’s what you’re supposed to believe if you adhere to the mainstream economic view.

[3] There can be modest changes in employment through a supply-side effect. If the trade deal increases the efficiency of the economy, then the marginal product of labor should rise, leading to a higher real wage, which in turn should induce some people to choose work over leisure. So the trade deal results in more people choosing to work, not an increased demand for labor.

[4] For those worried about brain drain from developing countries, there is an easy fix. Economists like to talk about taxing the winners, in this case developing country professionals and rich country consumers, to compensate the losers, which would be the home countries of the migrating professionals. We could tax a portion of the professionals’ pay to allow their home countries to train two or three professionals for every one that came to the United States. This is a classic win-win from trade.

[5] The loss of manufacturing jobs also reduced the wages of less-educated workers (those without college degrees) more generally. The displaced manufacturing workers crowded into retail and other service sectors, putting downward pressure on wages there.

[6] As a technical matter, the Federal Reserve Bank of New York is a private bank. It is owned by the banks that are members of the Federal Reserve System in the New York District.

“Markets are never just given. Neither God nor nature hands us a worked-out set of rules determining the way property relations are defined, contracts are enforced, or macroeconomic policy is implemented. These matters are determined by policy choices. The elites have written these rules to redistribute income upward. Needless to say, they are not eager to have the rules rewritten which means they have no interest in even having them discussed.”

======================================================

It is one of those remarkable hypocrisies that free “unregulated” trade requires deals of thousands of pages….

but if these deals weren’t so carefully structured to help the 1%, support would melt like snowmen in Fresno on a July day

Sometimes I wonder if people who seam to love market efficiency know that Mr. Market finds failing to spend 100% of your income immediately very inefficient.

Any other way to buy a paperback copy than via Amazon [which is where the link takes me]?

I refuse to use them/it.

It’s also at BarnesandNoble.com.

Or check your local indy, or one of those that take orders (I refrain from naming my favorite co-op in Chicago, and anyway I admit there are others). Nice to support those when you can.

I downloaded the complete pdf directly from the link…time to make a donation to the CEPR, I reckon.

There’s also this, which can help to find an independent bookseller in your area:

http://www.indiebound.org/book/9780692793367

Actually I believe there were some Republicans who denounced the Wall Street bailout as a violation of capitalist principles. My state’s Mark Sanford comes to mind. It was the Dems at the urging of Pelosi who saved the bailout. On the other hand many of my local politicians are big on “public/private” partnerships which would be a violation of laissez-faire that they approve. Perhaps it was simply that there are no giant banks headquartered in SC.

The truth is there is no coherent intellectual basis to how the US economy is currently run. It’s all about power and what you can do with it. Which is to say it is our politics, above all, that is broken.

“That is how the economics is supposed to work. In the standard theory, general shortages of demand are not a problem.[2] Economists have traditionally assumed that economies tended toward full employment. The basic economic constraint was a lack of supply. The problem was that we couldn’t produce enough goods and services, not that we were producing too much and couldn’t find anyone to buy them. In fact, this is why all the standard models used to analyze trade agreements like the Trans-Pacific Partnership assume trade doesn’t affect total employment.[3] Economies adjust so that shortages of demand are not a problem.”

Unbelievable.

By the 1920s they realised the system produced so much stuff that extensive advertising was needed to shift it all.

One hundred year’s later, we might take this on board.

What is the global advertising budget?

The amount necessary to shift all the crap the system produces today.

Demand has to be manufactured through advertising due to chronic over-supply.

We need to move on from Milton Freidman’s ideas and discover what trade in a globalized world is really about.

We are still under the influence of Milton Freidman’s ideas of a globalised free trade world.

These ideas came from Milton Freidman’s imagination where he saw the ideal as small state, raw capitalism and thought the public sector should be sold off and entitlement programs whittled down until everything must be purchased through the private sector.

“You are free to spend your money as you choose”

Not mentioning its other meaning:

“No money, no freedom”

After Milton Freedman’s “shock therapy” in Russia, people were left with so little money they couldn’t afford to eat and starved to death. In Greece people cannot afford even bread today.

But this is economic liberalism, the economy comes first.

Milton Freidman used his imagination to work out what small state, raw capitalism looked like whereas he could have looked at it in reality through history books of the 18th and 19th centuries where it had already existed.

The Classical Economists studied it and were able to see its problems first hand and noted the detrimental effects of the rentier class on the economy. They were constantly looking to get “unearned” income from doing nothing; sucking purchasing power out of the economy and bleeding it dry.

Adam Smith observed:

“The Labour and time of the poor is in civilised countries sacrificed to the maintaining of the rich in ease and luxury. The Landlord is maintained in idleness and luxury by the labour of his tenants. The moneyed man is supported by his extractions from the industrious merchant and the needy who are obliged to support him in ease by a return for the use of his money. But every savage has the full fruits of his own labours; there are no landlords, no usurers and no tax gatherers.”

Adam Smith saw landlords, usurers (bankers) and Government taxes as equally parasitic, all raising the cost of doing business.

He sees the lazy people at the top living off “unearned” income from their land and capital.

He sees the trickle up of Capitalism:

1) Those with excess capital collect rent and interest.

2) Those with insufficient capital pay rent and interest.

He differentiates between “earned” and “unearned” income.

Today we encourage a new rentier class of BTL landlords who look to extract the “earned” income of generation rent for “unearned” income. If you have a large BTL portfolio you can become a true rentier, do nothing productive at all and live off “unearned” income extracted from generation rent, the true capitalist parasite. (UK)

The Classical Economists realised capitalism has two sides, the productive side where “earned” income is generated and the unproductive, parasitic, rentier side where “unearned” income is generated.

You should tax “unearned” income to discourage the parasitic side of capitalism.

You shouldn’t tax “earned” income to encourage the productive side of capitalism.

You should provide low cost housing, education and services to create a low cost of living, giving a low minimum wage making you globally competitive. This is to be funded by taxes on “unearned” income.

The US has probably been the most successful in making its labour force internationally uncompetitive with soaring costs of housing, healthcare and student loan repayments.

These all have to be covered by wages and US businesses are now squealing about the high minimum wage.

That’s Milton Freidman’s imagined small state, raw capitalism.

What he imagined bears little resemblance to the reality the Classical Economists saw firsthand.

We need to move on from Milton Freidman fantasy land.

Milton Freidman fantasy land:

Businesses should maximise profit.

Small state, raw capitalism as observed by Adam Smith:

“But the rate of profit does not, like rent and wages, rise with the prosperity and fall with the declension of the society. On the contrary, it is naturally low in rich and high in poor countries, and it is always highest in the countries which are going fastest to ruin.”

When rates of profit are high, capitalism is cannibalising itself by:

1) Not engaging in long term investment for the future

2) Paying insufficient wages to maintain demand for its products and services

In the 18th Century they would have understood today’s problems with growth and demand.

Luckily Jeff Bezos didn’t inhabit Milton Freidman fantasy land.

He re-invested almost everything to turn Amazon onto the global behemoth it is today.

‘The commitment to an anti-inflation policy is a commitment by the government, acting through central banks, to keep wages down.‘

This is strikingly silly. Insert the word ‘nominal’ before wages, and it’s not a howler anymore.

Anti-inflation policy in fact has little influence on real wages (the variable of concern, not nominal wages). But it has a lot to do with preventing the social chaos of constantly rising prices, strikes for higher wages, inability of first-time home buyers to borrow at affordable rates, and so on.

Inflationism is greasy kid stuff … not to mention a brazen fraud on the public.

As one who walked the corridors of power in a very modest capacity in my country in the early to mid 1990s, can I just say that people with power or influence then were aware that globalisation would create winners and losers. I recall the consensus of those I knew then was that steps would need to be taken to compensate the losers. The tragedy is that these steps were never taken, or, if they were, only to a wholly inadequate degree.

The always elusive referents for cost, price and value…the flip-side of social chaos would seem the entropic degradation of wasted lives, excluded from participating {either-OR} abandoned as irredeemable…

Your assertion that anti-inflation policy has little influence on real wages does not address Baker’s statement about the mechanism by which he says it does. Given an argument between two people, one of whom cites a mechanism he is probably prepared to document with numbers and one of whom merely declares his belief, which are people more likely to trust? Granted always, they should go look for the numbers before they fully accept the statement, his credibility is currently higher than yours on this subject.

Real wages roughly doubled from 1947 (when BLS data begins) through the late 1970s:

Over this same period, the nominal yield on 10-year Treasury notes rose from 2.5% to over 10%:

By contrast, since the 1970s real wages stalled, while interest rates round-tripped back to 2 percent.

Over nearly seven decades, the correlation is quite the opposite from that

made upclaimed by Dean Bonkers. Namely, real wages soared under a regime of steadily rising nominal interest rates.Numbers — they can be crunchy sometimes.

Since my original reply has disappeared in limbo, I will merely note that numbers are probably even crunchier when you don’t generalize across a span of decades: first there was A, then there was B, nothing else happened. It’s a sure way to obscure patterns.

And Jim, please quit the ad hominem stuff! It’s ugly and needless. If you really have an argument you don’t need it, and if you don’t you don’t gain by it. You know perfectly well he’s not making things up and he’s not bonkers. When you say stuff like that, the obvious presumption is that you just don’t want to consider his arguments because they lead somewhere you don’t want to go.

Don’t feed the troll

I don’t think Jim is a troll; he can be very witty and has good historical insights. He is, however, an example of how an otherwise intelligent person can become a victim of a cult. It would also be terrible if we fell prey to group think here. Long may Jim continue to post.

Perhaps I am missing the point being made, but if you are suggesting that increases in real wages in the 1945-1975 period caused inflation, why not provide the data on inflation which would in fact show that inflation was essentially tame for 20 years in this period (1952-1972, with a slight hiccup in 1969-1971), thereby contradicting your point? And if you are suggesting that Fed increases in interest rate have not resulted in suppression of wages you will have to demonstrate that using analysis that takes into account the lag in time between increase in rate and transmission to wages, and in that case would you not also use the Fed Funds Rate itself as a variable?

Bulltwacky, they have been globalizing wages downwards while globalizing housing prices upwards!

Every time some stupid and moronic newsy floozy on one of the CorporateNonMedia outlets claims housing purchases may be going down because consumer confidence is plummeting, they CHOOSE to ignore the foreign buyers of said houses!

It’s all connected — it’s all rigged . . . .

Did I get this right? Full employment is an assumed boundary condition and so is fixed balance of trade? If the model is to work as advertised then the boundary conditions must be hard wired to be true, right?

Dean hits it out of the park once again!

Sounds like a great book on every level.

If the top 25 hedge fund managers saved around $5 billion per year in being taxed on their income at capital gains rate (carried interest ruling in tax code — utterly corrupt), then think of the amount that is being robbed from the tax base when one considers ALL the hedge fund people, and ALL the private equity types (who also do this), a conservative amount of tax revenues remitted should be around $100 billion per year!

Now that would go far . . .

or against the elimination of government deposit insurance that is an essential part of a stable banking system. [bold added]

Stockholm Syndrome since obviously deposits in a Postal Checking System would be inherently risk-free since:

a) the monetary sovereign cannot go broke.

b) the monetary sovereign should not lend to the private sector.

So government provided deposit insurance is NOT needed except as a means to force the poorer to lend (a deposit is legally a loan) to banks to lower the borrowing costs of the richer.

“We have met the enemy and he is us” Pogo