Yves here. From time to time, I’ve stated that in light of Brexit, the UK should have a war-level planning and industrial strategy project underway. The island nation already has a large trade imbalance that is destined to become worse as the EU takes chucks out of US export businesses as a result of Brexit. Financial services and transportation industry manufacturing (car, truck and airplane parts) are two area of vulnerability.

It turns out that the Tories are not being completely remiss, despite “industrial policy” being a dirty word in business and neoliberal circles. As the post below describes, the Government, with little fanfare, has presented a Green Paper in which it set forth a first draft of “industrial strategy”.

However, “industrial strategy” means among other things providing government backing for what the Japanese liked to call “national champions” as in industries where the nation could develop a competitive advantage. In the US, communications, computer and defense hardware and software have long been explicit national priorities, along with the pharmaceutical business, via the large investments in research paid for via the National Institutes of Health and other Federal agencies. And in Australia, the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation did R&D in a set of sectors like viniculture where Australia had the potential to become a strong player (CSIRO played an important role when I was in Australia in the early 2000s; I gather it is a shadow of its former self).

However, the US more often has had industrial policy by default, as in powerful industries getting support regardless of whether it would benefit parties beyond the incumbents, or would otherwise produce damaging distortions. For instance the banking industry is so heavily subsidized as to not properly be considered private enterprise and as a result has grown faster than the economy as a whole. Yet a raft of recent economic studies have concluded that overly-large financial services industries are a drag on growth, and America’s clearly falls in that category.

The nascent industrial strategy plan underscores one of the Big Lies of Brexit: that the UK would be able to free itself from supposedly overbearing EU rules. As the below post details, even the mild version of industrial policy that is palatable to Tories appears to be against the provisions that the EU gets in most of its trade pacts and it would almost certainly require in the upcoming trade negotiations.

We identified this as an issue in December:

Putting aside the substantial difference in size between the two economies, the fatal flaw of this logic is that the UK cannot be meaningfully sovereign due to its degree of economic integration into the EU. They’ve run up against Dani Rodrik’s trilemma, which he first wrote about in 2007:

Sometimes simple and bold ideas help us see more clearly a complex reality that requires nuanced approaches. I have an “impossibility theorem” for the global economy that is like that. It says that democracy, national sovereignty and global economic integration are mutually incompatible: we can combine any two of the three, but never have all three simultaneously and in full.

Here is what the theorem looks like in a picture:

To see why this makes sense, note that deep economic integration requires that we eliminate all transaction costs traders and financiers face in their cross-border dealings. Nation-states are a fundamental source of such transaction costs. They generate sovereign risk, create regulatory discontinuities at the border, prevent global regulation and supervision of financial intermediaries, and render a global lender of last resort a hopeless dream. The malfunctioning of the global financial system is intimately linked with these specific transaction costs…..So I maintain that any reform of the international economic system must face up to this trilemma. If we want more globalization, we must either give up some democracy or some national sovereignty. Pretending that we can have all three simultaneously leaves us in an unstable no-man’s land.

In other words, if the UK wants to have more national sovereignity, it must become more economically self-sufficient, as in more of an autarky. Yet making that sort of change would require a national economic policy, meaning having the government identify sectors where the UK has or could develop competitive advantage and do more to promote their growth. The failure to do planning (and better yet, some preliminary execution) means the UK, despite the phenomenal arrogance and ignorance of its officials, is approaching these negotiations as a beggar: it wants and needs to preserve substantial elements of the status quo, such as access to the single market and passporting rights for UK financial institutions, or face meaningful shifts of activities out of its economy (and please don’t try the dubious statistic that the EU will face bigger trade losses than the UK. What matters isn’t the absolute dollar, or in this case, pound and Euro hit, it’s the cost of the losses relative to the size of the economy. Measured properly, UK citizens will suffer considerably more than their EU counterparts).

And that’s before you get to the fact that this sort of industrial policy is anathema to Thatcherites and neoliberals.

As they say in Maine, you can’t get there from here. While greater national sovereignty is an estimable goal, the UK has gone down a path for decades that means it will take a long time to get the economic independence that would allow it to have more political autonomy. And despite all their bluster, UK leaders aren’t taking that objective seriously either.

By Nicholas Crafts, Professor of Economics and Economic History at the University of Warwick and CEPR. Originally published at VoxEU

The UK government has both embarked on Brexit and announced the outline of an ‘industrial strategy’ (HM Government 2017). The two initiatives are more closely related than is generally recognised because leaving the EU could mean a relaxation of rules controlling state aid, while the new supply-side approach entails a shift towards selective industrial policy.

Should we see this as an exciting new opportunity to build a stronger economy or as an unwelcome threat to the making of well-designed economic policy? In two recent papers, I argue that the latter is nearer the mark than the former (Crafts 2017a, 2017b).

State aid is defined by the EU as interventions – including grants, subsidies, loans, guarantees, and tax credits – that give the recipient an advantage on a selective basis that has distorted or may distort competition and which are likely to affect trade between member states. These are generally prohibited, but there is a broad exemption for horizontal industrial policies deemed to address market failures with relatively slight implications for trade.

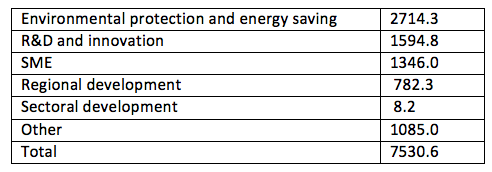

State aid has to be notified to and approved by the European Commission, whose decisions are subject to scrutiny by the EU courts. Under this regime, UK expenditure on state aid has been relatively low: in 2014, it was 0.33% of GDP. Table 1 reports the main categories of expenditure and also notes spending on sectoral development; this was only about 0.1% of the total.

Table 1. UK expenditure on state aid, 2014 (million euros)

Note: total excludes agriculture and transport.

Source: European Commission (2016)

If, following Brexit, the UK chooses to stay within the European Economic Area (EEA), rules on state aid would remain much the same. Selective industrial policy would generally remain illegal.

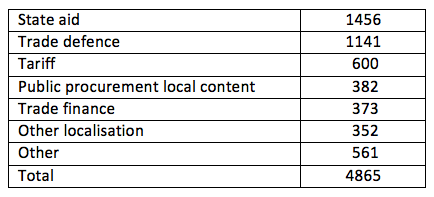

If, as seems more likely, the eventual outcome of Brexit is a trade agreement between the EU and the UK, the implications are somewhat less clear. Nevertheless, it seems quite likely that the EU would insist on continuation of the equivalent of EEA rules and enforcement mechanisms: a majority of existing EU trade agreements have legally enforceable rules on state aid (Hofmann et al. 2017). On the other hand, a hard Brexit with a default solution of WTO trade rules would allow much more scope for selective industrial policy as is underlined by the recent surge in ‘murky protectionism’ (see Table 2).

Table 2. G20 protectionist measures recorded by GTA (2009-2016)

Source: Evenett and Fritz (2016)

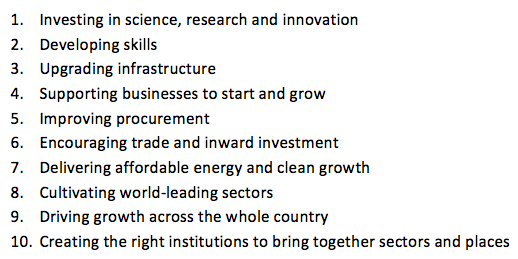

The Green Paper (HM Government 2017) aspires to deliver “a stronger economy and a fairer society” so that “more people in all corners of the country share in the UK’s success”. It identifies ten pillars for the new industrial strategy (see Table 3).

Table 3. The 10 pillars of UK industrial strategy

Source: HM Government (2017)

It is conventional to distinguish between ‘horizontal’ and ‘selective’ industrial policy. The former addresses economy-wide issues with a view to correcting market failures and removing policy distortions. Well-designed policies can improve productivity and perhaps have a small positive impact on the rate of economic growth. Many of the ten pillars, especially the first three, are essentially of this horizontal type.

The latter – selective industrial policy – entails interventions that favour particular sectors and/or categories of investment, skills, technologies or places. The fifth, sixth and especially the eighth pillars can be seen as explicitly selective policies.

The most eye-catching new policy initiative relates to the pillar “cultivating world-leading sectors” in terms of a proposal for “sector deals”. The Green Paper indicates that the government is prepared to work with any sector that can organise behind strong leadership to help deliver upgrades in productivity. This could involve addressing regulatory barriers, promoting competition and innovation, working together to increase exports, and working together to commercialise research.

To complement this, it is intended to take a strategic approach to government procurement to support investment in innovation and skills. All major government projects will be structured so that UK-based suppliers are in the best position to compete for contracts.

There will also be a new, more strategic approach to inward investment. This clearly envisages giving more inducements for foreign direct investment in projects that are judged to have a greater impact on economic growth.

Taken together, these three announcements signal an intention to rebalance industrial policy towards a distinctly more selective stance.

The proposed horizontal policy reforms to innovation, infrastructure, and skills can happen with or without Brexit, whatever the flavour of Brexit. The obstacles to better policy in the past have been located in Westminster, not Brussels. It is difficult, however, to believe that the proposed moves towards selective industrial policy would be allowed under EU rules on state aid.

If a high priority is attached to pursuing a return to state intervention, then that in itself would be a reason to choose a hard Brexit. If, on the other hand, a high priority is attached to controlling the politicisation of industrial policy, then an attractive aspect of a trade agreement with the EU is that it would provide a commitment technology to constrain ministerial discretion.

The problem with selective industrial policy is that government failure is highly likely. It has been widely remarked that, as in the UK in the 1970s where such policies were an expensive failure (Morris and Stout 1985), support is disproportionately given to declining rather than new industries, and this may be an inherent aspect of the political economy of industrial policy that slows down the process of creative destruction (Baldwin and Robert-Nicoud 2007).

Protection against the ravages of industrial decline is probably what many pro-Brexit voters want: it has largely been precluded by EU membership, but it is a likely outcome of a newfound concern to help the ‘left-behind’. But the constraint on political discretion arising from EU rules on state aid has been helpful since inhibiting the exit of poorly performing firms and industries is not good for long-run productivity performance.

In any case, it is highly desirable that as the government formulates its industrial strategy, it pays attention to the institutional architecture (LSE Growth Commission 2017). A framework is needed not only to replace EU rules on state aid but also to provide appropriate oversight of the whole gamut of industrial policy. This is highlighted by the recent deal with Nissan, which sets an unfortunate precedent, especially since this is surely only the first of many companies that will threaten to move production to locations inside the Single Market.

Policy guidelines for intervention should be made public and transparent, and evidence-based evaluation both ex ante and ex post by an independent body is required (Banks 2015). The chances of this approach being adopted in UK policymaking have always been remote and, no doubt, it is even less likely in the current political climate.

A recent poll of economists finds that a large majority thinks that it is time for a new industrial strategy, but at the same time they doubt that the government could implement one successfully (Den Haan et al. 2017). I share these opinions. And hard Brexit reduces rather than enhances the likelihood of success since it increases the scope for bad policymaking.

See original post for references

Nostalgia and immanence. Sovereignty, by whom and for whom? Scotland is being screwed. Here is an excerpt from Anthony Barnett’s article.

“The EU is currently in charge of agricultural and fishing policies, two issues of great importance for Scotland. If these powers went to the Scottish parliament and government after Brexit, their responsibility would be increased considerably. This was the potential upside of Brexit for her, that Sturgeon expressed an interest in immediately after the referendum vote went against Remain. It would mean, however, that when London wants to negotiate new trade agreements with other countries round the world, it will need Scotland’s approval for any terms that cover trade in food and fish stocks. Instead of a ‘nimble’ UK government negotiating with the US, for example, on the import of their cheap, hormone-raddled steaks in return for exporting financial services, Edinburgh will object because of the need to protect its Angus herds. The prime minister has warned she is in no mood to permit this. In other words, what Theresa May calls “the fundamental unity of the British people which underwrites our whole existence as a United Kingdom”, could turn out to mean the authority to sell out Scotland in the name of her, “new ‘collective responsibility’”.”

The full article here, https://www.opendemocracy.net/anthony-barnett/brexit-is-old-people-s-home

On 9 June Sturgeon will see a different poll result. Scotland has 5 million people the same as Yorkshire yet gets £1500/head higher Government Spending and a £20 bn subsidy from England. It has no passports, no currency, and no taxation policy. It has the ability to raise its own local Income Tax but refuses because it knows the consequences.

Scotland has no authority over coastal waters or mineral rights these reside in The Crown. SNP is a busted flush.

I hope we will relieve you of this terrible burden as soon as possible.

No doubt Yorkshire will flourish without us.

Any supposed higher spending is in the hands of westminster,raising income tax in one region of the uk would have considerable costs and there is no guarantee any extra revenue would not be offset by a recuced block grant.

Of course it doesn’t have any of these things you list, as it is not an independent country yet.

You may not like the SNP, but with 56 out of 59 seats at westminster, twice the votes of its nearest rival in holyrood and 120,000 members, its hardly a busted flush

It was something watching the back and forth between T May and SNP and the latter circumventing the

overwhelming vote by the Scottish to stay in the EU. One of the things I miss from Nicholas Crafts is addressing the UK bilateral agreements with the rest of the world vis-a-vis UK’s being part of the EU. Many European economists-i.e. Nino Becerra, Standhal- deem UK’s upcoming new faculty to negotiate without the EU strings attachment very favorable to the kingdom, or at least to many of its most powerful agents. Also the binomial opposition autarchy/globalization deserves a deep scrutiny; as Theresa May puts it, “for the good we can do together in the world,as a Global Britain”

Overwhelming vote of Scots to stay in UK 2014

http://www.bbc.com/news/events/scotland-decides/results

Following the logical order of a timeline will be helpful here. The referendum you are referring to was evidently prior to Brexit’s ref. As you know, the most important “bullet point” to persuade the Scots to vote against independence was the automatic removal and very dubious posterior readmission to the EU. You should know this since it is SNP current out loud complaint.

SNP will have no seats in Westminster until it secures them at the polls in June. Scotland receives £20,000,000,000 from England to play Socialism with OPM. Without England Scotland would need 40% VAT to pay its way.

http://scot-buzz.co.uk/the-truth-about-scotlands-finances-trying-praying/

Of course Germany and France would send economic aid.

You are referring to Government Expenditure and Revenue in Scotland

(GERS) figures, which were designed to paint a bleak picture of Scotland’s position within the UK by the then Tory Scottish Secretary, Ian Lang:

“This is an initiative which will allow us to score against all of our political opponents.”

A subtler approach than the deep sixing of the McCrone Report

Read this

Listen to this, Richard Murphy (Tax Justice) vs Kevin Hague (widely published pet food salesman)

It has nothing of worth to say about an independent Scotland’s financial position.

If playing at socialism means trying to ameliorate vindictive tory policies such as the bedroom tax and resisting the privatision of the national health service north of the border, I’ll take it all day long.

If we are such a basket case, why not just let us go?

The North Sea oil belongs to Scotland. That should help. And I’ll bet the existing pipelines strongly encourage England to buy North Sea oil.

History: England has ripped off Scotland for 400 years. During WWI, just 100 years ago, it was a running joke that the Scots soldiers were short – that is, undernourished. Reparations are owed, hence the existing money flows.

North Sea oil is pretty much tapped out.

I’ve heard that, but I gather they’re still pumping. How much is “pretty much?”

An argument against independence might be that it would force the Scots to frack the North Sea, a bad idea.

Pursuant to my historical point: this also means the Scottish economy is largely the result of English imperialism over the centuries (for example, English overlords forced a shift from cattle to sheep, partly for the “dark satanic mills” and partly because shepherds are less formidable than cattle herders. The impact on the landscape was huge.) One wonders what the Scottish economy would look like without that distortion. Of course, German and French overlordship would hardly be better.

That said, the Highlands are a hard place to make a living; that’s why they made hard people. I confess my take on Scotland is largely romantic; I don’t have to live there, despite a lot of Scots ancestry. Economic reality led to a “No” vote before and is likely to do so again.

A large section of the Labour Party understands this and want hard BREXIT – they seem more aware of the difficulties in BREXIT than many former REMAINers now campaigning for soft BREXIT (stuff that has been well reported on here).

I’ll get a better idea how strong they are in the Labour Party these days later today when I complete my modelling from the choice experiment, which now seems to have been ideally timed…..I’m afraid the “Islington Set” still wield disproportionate power and could not win the election for Labour – they are loathed in areas like here in the East Midlands. Interestingly the East Midlands values free movement of people the most of any of the 12 counting regions in the whole UK….and this support is due to less fetishisation of free trade etc.

Either go for “proper” right-wingers or old Labour – not dissimilar to choices made by people in the USA

Clueless American lefty here who looked on with hope as Corbyn rose to leadership. So what were the main contributing factors in his apparent decline? My fear is that the politics of “personality” (particularly amongst the young) had as much to do with his rise (and fall) as Sanders here in the US with the latter dodging a bullet by not gaining too much power too quickly. Oh and thanks for introducing me to the term “Islington Set”!

There is a concerted campaign by former-Blairites to get rid of him – my local MP was part of the “not-so-random” set of resignations from the shadow cabinet just after the referendum to try to destabilise Corbyn.

Corbyn, let’s be honest, hasn’t helped himself – he’s made unforced errors and as someone who was a serial troublemaker for 30 years was always going to find it hard to get support in the Parliamentary Party (which largely dictates the news agenda). I do thnk that, like in the USA, there is a solid bunch of young people who want profound change. The trouble is a lot of them “don’t get it” when it comes to how to effect this – i.e. turn up at the voting booth. My data show that 8 percentage points of the 28% who did not turn out last year may have been younger politically engaged REMAINers who think that “likes” and “retweets” lead to change. They learned the hard way.

Corbyn’s problems are:

A parliamentary party that openly undermines him

All mainstream news is opposed to him,including the guardian,BBC, and after the last attempt to remove him have chosen to ignore him.

(If Treeza pulled out a walther ppk at the dispatch box and gave him two in the head, that might just make it into the news)

His team are pretty ropey, John McDonnell especially. They have failed to present any compelling picture for the voters.

Agreeing to a snap election is just the latest blunder, he should have let the tories swing for another 3 years.

I’m sorry, but blaming it on everyone but Corbyn is pretty weak. Politicians don’t get given a choice who to work with – be it their colleagues/enemies/voters. That’s what makes a good political leader – that they can figure out how to work with what’s there vs. what they wish would be there.

From what I can see, Corbyn DOES NOT KNOW how to work with anyone who disagrees with him. TBH, he never had to master that skill, and at his age it would be amazing if he was able to learn it (as it’s bloody hard). And I’m not talking only about Labour internal politics, as he could deal with those from a position of power if he wanted to/knew how very efficiently.

And not being able to work with people who disagree with you (which is different from doing as they say I’d point out) is a major problem in a political leader.

I’d agree Corbyn’s made lots of unforced errors……the irony is his “brand” of politics could, if tweaked to play up certain things in most regions, whilst play down the “industrial policy and hard BREXIT” stance (in say, London), win Labour the election IMHO. But he himself is not the best standard-bearer for this at all. As you say, he MIGHT be able to do it, but the odds don’t favour it, given his character etc.

I think its hard to work with people who don’t want to work with you.

When you have the greasy eminence,mandelson, happily announcing:

“I work every single day to bring forward the end of [Corbyn’s] tenure in office. Every day I try to do something to rescue the Labour Party from his leadership.”

We’ll probably never know about Corbyn abilities, but we can say that he has not really had a fair shake of the stick.

Voting for an election to suit treeza,however, does show extremely poor judgement.

You mean Blair, Thathcher you-name-them etc. didn’t have insiders working on dethroning them every day? That they got a free pass?

The point is, NO one will have a fair shake of the stick, that’s the start line. Yet, some do manage to get ahead better than others. Yes, it’s mostly disgusting power plays, but going into politics assuming it’s all fair-go is naive at best. And Corbyn was in play for long enough to know that, he’s not a fresh faced MP who never saw the parliamentary battlegrounds. From that perspective, someone like Ken Livngstone (as much as I dislike him) would be much more efficient.

That is not what I mean, the normal jockeying for position happened with them.

The closest example to Corbyn is Michael Foot.

At least his opponents had the decency/vanity to split, one of them, Vincent Cable eventually making it to the promised land of a conservative coalition.

The only thing I would add to the very comprehensive and accurate intro and the article itself are that energy production is also a key element of the de-facto US domestic industrial policy. Same commentary applies to that sector too — it’s by no means certain whether it should even be a industry which receives support, but nevertheless it does.

Adding a UK-centric note, politically speaking, it’s a perfect storm of leadership uselessness. As noted, one thing which would ameliorate (not cure) the problems resulting from a hard Brexit is a robust, well-executed industrial policy. “Picking winners” as it used to be called when I was a kid in the 1970’s. Auto manufacture (final assembly and subcomponents), pharmaceutical research, fashion design, media production, tourism, freight forwarding, telecommunications, legal services, financial services (yes, I know, this one does need caveats the size you could send an elephant through but it does have a place). In the same vein as yucky-but-necessary industries, you can also add nuclear waste reprocessing and decontamination, toxic chemical recycling and disposal and industrial process which require large volumes of potable water (which we have a lot of, but it carries a risk of discharging large effluent volumes if not rigorously regulated and inspected). It’s not entirely hopeless.

But the Conservatives, who are the most vociferous champions of a hard Brexit (it was, after all, their fault we had to make the choice in the first place and for reasons too complicated to distract us here the most likely to form the next government) are the least ideologically predisposed to having an industrial policy worthy of the name. Prisoners of free-market ideology as they are, they are the worst people to count on to do the right and necessary thing in the circumstances.

It is this dynamic that makes me think seriously about retiring to nicer shores. Eventually someone will figure out they need to do the right thing, but it won’t be this lot and by the time the penny drops, a shed load of damage will have been done.

Agreed on all counts.

But there is a chance that this will become a wave election – I was quite frankly astonished that my data show East Midlanders are perfectly happy to sacrifice ALL forms of European integration (SEM, Customs Union and yes, even a Free Trade Area that was so “hyped up” on UKIP billboards on the drive down the A1 from Nottingham down to Essex last year) to secure freedom of movement…….they appear to want “people to fill the gaps” and an industrial policy to help our current winners rather than cheap rubbishy imports. Hardly Conservative policies….which make me wonder if Corbyn might do better than everyone thinks….but it depends how in thrall he is to the Islington Set – and given his own constituency…..LOL!

I couldn’t find a link to the Green Paper, but if the quoted bits are an accurate summary of the content, it sounds more like a policy to have a policy. What skills? What infrastructure? Supporting businesses how? Which world-leading sectors?

The conclusion seems to be that economists think that government will come up with the wrong answers to those questions. I agree that seems fairly probable, although not inevitable. In any case, we probably won’t be able to judge until we have had a chance to look at the actual policy that the Green Paper states it will be their policy to create.

I agree, it sounded like a concept document preliminary to doing the real policy development. I have no idea how this part of policy-making is done in the UK. Input by informed readers very much appreciated!

“Green Papers” are proto-policies. They’re used to give a broad outline of what might (potentially) end up as legislation or statutory instruments.

For those interested in exploring this one further, here is the original Green Paper:

https://www.gov.uk/government/consultations/building-our-industrial-strategy

The aim of the exercise (as with most Green Papers) is, to quote:

Eventually, some Green Papers become proposals for being turned into statues, if they receive parliamentary approval.

I’ll also list here a useful compare-and-contrast between Presidential (US) and Parliamentary (a lot of the EU, Japan, Australia, amongst others) law making so readers can see how this bit of the process fits in and where the US equivalent is.

If recent history is anything to go by, debate and information-dissemination will *follow* the decision, rather than precede it…..my data are interesting in that although public policy decisions are notoriously hard to model (especially a 5(+) dimensional one like BREXIT), I’m quite surprised at how simple the “translate your attitudes into a vote” turned out to be. (Basically there are only 4, arguably 3 clusters).

This reflects almost a year of discussion of BREXIT in the news……I’d argue that only now are people anywhere near able to vote on it. Thus, if it is a major issue in the general election, then the result will be an effective “revote” on it. Both the Conservatives and Labour are in trouble.

The Tories are split by which type of BREXIT they want, whilst Labour polarises between “hardcore REMAINers” and “Hard BREXIT” supporters. The latter are, BTW, not stupid. They are some of the most consistent supporters in the population and show the classic “more education = more consistency” result in choice modelling, something that is lacking in the REMAIN data, suggesting REMAIN support is shallow. I’m desperately working ASAP to get my report out. I never dreamed it would become so timely……

The major decisions in UK 20th Century involved NO Consent whatsoever. Churchill was not elected in May 1940 when he decided to bomb Moenchengladbach on 11 May and Cologne on 12 May to break up Peace Talks between Dahlerus and Foreign Office and avoid being overthrown.

No popular consent to Secret Sessions of Parliament, Press Censorship, no Elections 1935-45 – indeed in 1945 Churchill did not want elections but Labour insisted. No discussion even with British Empire when war declared in 1914 or 1939.

No discussion on Local Govt Reorganisation 1972; no discussion on joining EEC in 1972; no discussion on Decimal Currency 1971, no discussion on Kosovo War, Iraq War, Libya War.

BreXit has been the exception to this rule of ignoring The Public

Add to this no discussion on the 2012 Health and Social Care act which removed the duty of the govt to provide cradle to grave free healthcare to every UK citizen It paved the way for the present break-up and sell-off of our uniquely humane and cost-effective National Health Service (the only thing we had, as a nation, to be truly proud of). It is currently being starved of funding, generally and deliberately rendered dysfunctional and sold off in chunks. As my GP told me recently, “it is being set up to fail, we, the GPs could solve its current problems, claimed to be intractable, in a week”. Most of the country has no idea of the passing of the 2012 act or its contents and also little idea of what we are in the process of losing – and forever. The plan is to have an insurance based US style “health service” and everyone here knows how well-loved, successful and cost-effective that is! Sorry if this is a bit off topic, but it does illustrate the point made by Paul above.

Green Paper in former British Colonies and EU are Discussion Documents put out to invite submissions before policy emerges in a White Paper expressing Intent.

ChrisPacific: it sounds more like a policy to have a policy. What skills? What infrastructure? Supporting businesses how? Which world-leading sectors?

Agreed. That Table 3, setting out its 10 pillars of UK industrial strategy, is utterly vacuous.

How can democracy and nation sovereignty be separated, as is suggested in the article?

It seems we have a binary choice, democracy and national sovereignty OR global economic integration.

Please enlighten me.

International democracy. You can argue it exists in the UK. Several nations- England, Scotland, Wales – one overall government.

The point is in a democracy, people will rebel against deep economic integration. See Brexit and Trump. Problem is those revolts may not be effective and/or the cure will be worse than the perceived disease (UK too dependent on immigrants to get rid of them save at very high societal cost; Brexit will serve as an excuse for crushing labor by getting rid of EU labor protections).

In a system with less democratic accountability, you can ignore the unhappy public.

I would really appreciate a position paper to prove that particular thesis

A drive-by take on the current situation with regards to the NHS and British agriculture. Fair enough, as things stand.

Agriculture requires Seasonal Workers on work permit not Permanent Residents in Boston distilling vodka in lock-ups or Portuguese living in shanties

An internet search engine is your friend. There’s plenty of data and discussion of immigration impact on GDP in the UK on the web. A most cursory enquiry should sate your enquiry.

Plus, there was a post on Brexit on nakedcapitalism.com yesterday which has some data figures regarding immigrant and migrant labour required in the both the NHS and agriculture. As you commented within that post, you must have read the article.

Could you also provide us with a paper supporting your, mostly, counter factual statements regarding Scotland and the SNP in your first post on this article. A cursory search of the internet shows that bloc grants do not favour Scotland, that power to raise revenue has been thwarted by delays and obfuscation by Westminster (not to mention the reneging on earlier promises pre-referendum), and so forth.

In fact it would take a fairly detailed paper with historical references to counter the unsubstantiated claims made in that comment.

Rather than ask the commentariat to satisfy you with proof, you might, instead, provide us with proof, rather than opinions, of your assertions regarding Scotland and the SNP?

best regards

Paul is a Royalist. He stands with the queen. No proof offered or required.

How crass of you….

What did I eat for breakfast this morning, you so knowledgeable one ? Why should I be a “Royalist” for stating what bunkum your statements on immigration are. You really need “self-employed Romanians” to sell Big Issue in the UK ?

http://www.nakedcapitalism.com/2017/04/henry-vii-clauses-britains-great-repeal-brexit-bill-gives-government-unprecedented-powers.html#comment-2793403

You’re getting cute again. Breakfast? Maybe some straw?

Scotland has always had the power to raise 3p in £ additional tax. As for NHS, there no is no need for foreign workers. The BMA restricted access to UK Medical Schools and thus created a shortage of medics. Thousands of applicants are rejected with better grades than many of the foreign doctors imported, who incidentally have far higher rates of GMC Offences for which they are struck off.

As for Nurses, Thatcher sold off Nurses Homes which were ideal for single and trainee nurses to be on site for shift work. 26,000 nurses quit last year alone. They recruited 21,000 to replace them. It is poor management not shortage of nurses. Pay is better for those working as Agency Nurses leased back to NHS.

more coulda, woulda, shoulda, re the NHS (and post brexit … the 3 pence question? … will it still exist in more than name only?)… and the thatcher nostrum thrown out doesn’t substantially address immigration issue in meaningful manner … and if the NHS doesn’t need all them foreigners, why are they there? Is it just a soft spot that many in the UK have for the hapless foreigners that they decided to give them jobs? (hint: the other one’s got bells on it.)

The revenue streams which Scotland receive and which they can legally obtain through the various legal taxation which have been begrudgingly handed over from Westminster do not meet expenditures because they were never meant to. The London government does not want a Scotland that can independently chart a different economic course from that of Austerity Tory England. Might set a bad example by providing adequately for all its people, and we can’t be having that.

And there is still plenty of data and economic analysis of the impact of immigration/migration/emigration on the UK for one to peruse on the web. It’s very possible that a number of conclusions can be determined, maybe quite complex ones.

UK had an Industrial Policy 1964-70 but it was dismantled by Heath then Thatcher. Selective Employment Tax and distribution of Govt offices around the UK were designed to re-balance away from London. Nationalisation of Mines and Steel 1945 was to inject Capital into poorly capitalised industries and the same was true of consolidation of Aircraft and Shipbuilding in 1960s and again in 1974- creating British Shipbuilders and British Aerospace. BBC was nationalised in 1926 to stop GE taking over the British Broadcasting Company through Thomson-Houston.

GEC was encouraged to take over English Electric to consolidate scale.

ICI was created 1926 by Government policy to create a rival to I G Farben.

Chamberlain funded Rolls Royce to build Shadow Factories in Crewe and create subcontractor networks after 1935. He funded Radar and Merlin engines and Rearmament.

Rover was ordered to transfer jet engine business to Rolls Royce and the Barnoldswick Factory in return for R-R turning over tank construction to Rover.

1915 Rolls-Royce was ordered to enter aircraft engine production and copy the Renault engine but Henry Royce decided to build his own Eagle and stripped down Mercedes engines.

UK had an Industrial Policy until The Tories financialised things for The City and scrapped policy on manufacturing in favour of Speculation

One of the problems with industrial policy, as we have seen it up to now, is that we neglect its spatial and regional aspects.

In other words, any industrial policy will be faulty if it ignores that some parts of the country will get a lot of private investment, and others little or none. Some parts can also lose investment through outsourcing or an employer simply going out of business or moving elsewhere, as we’ve seen, woefully.

We saw the results of such policy lacks in the loss of jobs in the mid-West since the mid 1980s, resulting in part in Trump’s election.

Wise industrial policy could have created a more level jobs playing field by government investing in infrastructure in the regions and cities badly needing jobs, along with skill training and basic and advanced education, supporting local R+D, and supporting new and growing businesses.

Doing these requires that we overcome our fears of government intervention and look to government to craft a reasonable jobs future. Moreover, a deeper and more thoughtful industrial policy could have prevented Trump and the populist complaints.

A decent job doesn’t solve all life problems but it prevents many.

The US only accepts Industrial Policy through the Pentagram. Huge subsidies go to US business through DARPA and Pentagram. When GE was allowed to acquire RCA defence business and the Consumer business was spun off to Thomson of France which sourced from Hitachi, it was clear that Defence was the Protected Sector in the Reagan Industrial Policy just as Thatcher preserved Defence as the only protected sector of UK Engineering

Spot on Yves. We had a Ministry of Supply in WWII that did amazing work in keeping the lights on and we are going to need something of the same with Brexit.

Officials don’t have much authority in our system so it will require perseverance and dedication. After the last few decades of abuse, I frankly wonder if there are any first rate civil servants left for the job.

Am reminded that during WW2 Attlee effectively ran the domestic economy as Deputy PM whilst Churchill ran the war.

Attlee’s Labour party learned how to govern and indeed should have been in power 1951-55 but for one of those quirks first past the post occasionally throws up in that the party with the most votes fails to win the most seats. (Indeed I might be misremembering this but i believe he secured the only absolute majority of the eligible electorate in British history).