For the last few years, we’ve been writing about the many ways in which private equity does not live up to its billing. One beef has been that fees are excessive given that private equity has not outperformed over the last decade when you factor in its risks. Nosebleed prices for deals and even more money pouring into the strategy as desperate underfunded pensions hope private equity will salvage them means this inadequate performance isn’t likely to change anytime soon, if ever.

Oxford professor Ludovic Phallipou has estimated total private equity fees and costs at 7% per year. No one in the industry has roused himself to object to his estimate, which suggests if anything it might be low. Second is even with private equity managers charging fees that would be considered extortionate in any other type of asset management, many, including some of the very biggest fund managers, have been caught out regularly levying unauthorized fees and costs. That is called embezzlement yet oddly no one has seen fit to call in the cops.

Heretofore, the debate over private equity fees has been restricted largely to the trade press. A salvo of articles by Gretchen Morgenson in New York Times and Mark Maremont of the Wall Street Journal in 2014 about abuses by industry leaders such as Apollo, Bain, Blackstone, and KKR helped keep pressure on the SEC to sanction the questionable practices they’d exposed to the general public. But the big media coverage has been sporadic since then.

Moreover, the big question of whether private equity is worth its lofty cost has gotten less notice, but that may finally be changing.

Last week, Pew released a study, State Public Pension Funds Increase Use of Complex Investments, and findings weren’t at all positive about private equity. The reason Pew’s take matters is that Pew has the image of being independent, but if anything, it has a small c conservative orientation. So for an organization which no one would depict as anti-business or liberal to voice doubts about private equity is a significant development. 1

The Pew study covers some private equity topics we’ve covered regularly, such as: high fees relative to the risks, lack of transparency (which is an unduly polite way of saying investors don’t even know how much in total fees they are paying) and lack of consistent accounting (note that some pension funds report only returns gross of fees while others report net or both).2 The report also has some important findings about overall public pension fund results and behavior:

….only two of the funds examined exceeding investment return targets over the past 10 years….

While examples exist of top performers with long-standing alternative investment programs, the funds with recent and rapid entries into alternative markets—including signicant allocations to hedge funds—reported the weakest 10- year returns…

Many states have consistently achieved relatively high returns without a heavy reliance on alternatives. Plans in Oklahoma exemplify this approach. Both of the Oklahoma state-sponsored retirement systems examined have

lower-than-average allocations to alternatives; one holds no alternatives. Both, however, have 10-year earnings that outpace the median.

In fairness, the study highlights alternative investments generally, and not just private equity. We pointed out in 2006, in our very first post, that a careful reading of what CalPERS revealed about its experience in hedge funds was tantamount to saying it shouldn’t invest in them at all. Even as of then, there were cheap replication strategies that would allow investors to achieve returns that were not much or negatively correlated with the stock market at much lower cost than hedge funds. Starting around 2012, hedge funds became more and more correlated with equity, obviating that rationale.

A full eight years after we suggested that CalPERS ought to listen to itself and get out of hedge funds, the giant pension fund finally did just that. CalPERS shook the industry with its late 2014 announcement that it was exiting hedge funds and by early 2016, the combination of years of lackluster returns and high fees led more and more investors to reduce commitments or even pull cash out.

The Pew study report stresses that investing in more risky investments in the hope of getting higher returns is, well, risky:

Measures of volatility in investment returns are important to consider because that volatility creates budget uncertainty for state and local governments sponsoring plans. Between 2003 and 2013, for example, actuarially required pension contributions increased from 4 percent to 8 percent of state revenue to adjust for investment losses from the dot-com crash and the onset of the Great Recession.

And increased commitments to alternative investments is a big part of the “increased risk” story:

The Pew authors highlight that public pension funds fail to capture as much as half of the private equity fees they are charged, as this site and others reported, and that’s before factoring in carry fees. That means most public pension funds are understating their true investments costs by a large margin. The report drily notes:

If the relative size of traditionally unreported investment costs demonstrated by CalPERS, MOSERS, and the SCRS holds true for public pension plans generally, unreported fees could total over $4 billion annually on the $255 billion in private equity assets held by state retirement systems. That’s more than 40 percent over currently reported total investment expenses, which topped $10 billion in 2014. Policymakers, stakeholders, and the public need full disclosure on investment performance and fees to ensure that risks, returns, and costs are balanced to meet funds’ policy goals. Such assessments are unlikely when billions of dollars in fees are not reported.

Mind you, we believe this estimate is low, since fees charged to portfolio companies, which come out of investors’ funds, are not reported.

So in a a bit of synchronicity, the Wall Street Journal reported over the weekend that Calpers Is Sick of Paying Too Much for Private Equity. However, virtually all of this story is old news; you could have gotten all of the substance from our post five months ago, CalPERS Considers Cutting Out Private Equity Firms, Making Direct Investments in Companies, in which we reported on CalPERS’ past and current interest in reducing its reliance on private equity firms. So it’s odd to see the Journal taking up this story now.

Our 2016 post discussed at length how the giant public pension fund had considered setting up its own private equity arm in 1999, as some Canadian pension funds have done in recent years. CalPERS hired McKinsey, which gave a host of reasons why not to go there, the two biggest being the difficulty of recruiting and keeping “talent” and legislative bars to paying state employees incentive fees. But the bigger issue was that staff wasn’t keen about the idea. It didn’t help that McKinsey in general and the retired partner who curiously delivered the recommendation, former firm managing partner Ron Daniel, had glaring and undisclosed conflicts of interest.3

The news item last November was that CalPERS’ chief investment officer, Ted Elioupolos, said at a public board meeting that CalPERS was launching a serious study of whether and how to become a more direct private equity investor, meaning reducing its reliance on costly fund manager middlemen. From Pension & Investments’ write up:

CalPERS Chief Investment Officer Theodore Eliopoulos asked the retirement system’s senior private equity staff Monday to explore options to the change the $299.5 billion pension fund’s private equity program, including cutting out general partners and making private equity investments directly….

Other options that will be explored include increasing the number of co-investments and increasing the number of separate accounts with general partners, Mr. Eliopoulos said.

The detail in the Journal story does not add much to what Elioupolos said in public session last year:

Among the options being considered are: buying a private-equity firm or creating a separate company outside Calpers that would make private-equity wagers. Calpers could also choose to act as the sole investor in more customized accounts with outside managers, these people said….

In perhaps the biggest shift being reviewed, Calpers also may ask its staff members to make private-equity investments directly.

If you watch the board video below (or use this link here) starting at 1:32:30, you will see Elioupolos lay out all the options that the Journal bizarrely depicts as breaking news. He states that CalPERS is setting up a formal team to look at “all the possibilities,” including setting up a new company that CalPERS would staff. Eliopoulos names some of the participants and indicated that the project was starting but would really gear up in 2017.

And even though Eliopoulos is a master of speaking in a coded manner, he’s fairly direct here, and makes clear that a big impetus for the study is the magnitude of private equity fees, particularly for sought-after funds. Admittedly, there are some new tidbits in the Journal account, like “Calpers also is studying an increase in the pension fund’s $3 billion investment in customized accounts,” and that it is soliciting input from other funds that have done more direct investing.4 But they aren’t all that consequential.

So while it’s good to see the Journal calling attention to CalPERS’ skepticism over the need to pay big private equity fees, it would be nice if it has published the story up on some time other than over a big holiday weekend. And it would be even better if the Journal hadn’t made it CalPERS sound as if it was acting out of pique, as opposed to making a perfectly rational study of strategic options.

Last week also saw some dodgy defenses of private equity’s hefty charges. Yale’s endowment, which has earned sparking returns due to a outsized helping of successful venture capital funds, went to bat for its managers. From Bloomberg:

Yale University, one of the most-watched and best-performing college endowments, defended the fees it pays to external managers, saying in an annual investment report that a low-cost passive strategy would have “shortchanged’’ the Ivy League school’s students and faculty.

This is disingenuous. First, the comparison to passive investing is a straw man. The academics that have modeled strategies that yield returns that are generally better than private equity net of fees do so by targeting pubic companies that are the sort private equity would buy, and having rules as to how to rebalance and under what circumstances to sell. The limit on this sort of investing strategy is that if too many investors pursued it, the returns would fall. That makes it a questionable alternative for big public pension funds, but a more viable alternative for endowments, even a large one like Yale’s.

Second and even more important, Yale’s results are a big outlier and for a good reason. It made a monster China bet that paid off. Yale claims to have benefitted from intelligence from recent graduates in China. Even so, some storied venture investors like Sequoia are rumored to have launched doggy China funds, so Yale was either lucky or smart, depending on your point of view. By contrast, Larry Summers made an outsized swaps wager at Harvard, investing from the operating budget as well as the endowment, and blew up both.

Third, private equity and venture capital partners among Yale alumi are big donor targets. Even if Yale were to become disappointed with them down the road, one can be sure that nary a bad word would ever be said.

Finally, Dan Primack, who was the most visible private equity beat reporter when he was at Fortune, issued a sorry attack on an effort to rein in fees, including those of private equity, at the North Carolina pension fund from his new home, Axios.

Primack fails to substantiate his thesis:

Bottom line: Fees can indeed be problematic but, in North Carolina, most of the fees are actually tied to strong investment returns. Folwell doesn’t seem to connect those dots.

His only evidence?

Performance: The two asset classes that comprise the bulk of fees ― real estate and private equity ― also are the system’s two best performing asset classes (net of fees) over both a three-year and five-year period.

As readers know well by now, and Pew underscored, what counts is risk-adjusted returns, not gross returns. Primack is effectively arguing for measuring investments results via absolute returns. As we discussed in sordid detail in 2015, any finance student would be failed for making that sort of argument, as would anyone taking a professional certification, like a CFA. Primack ought to know better, so he is either not technically competent at his job or shilling for his sources. Neither possibility reflects well on him.

So how has North Carolina done in private equity relative to the investment risk? Unfortunately, North Carolina’s own private equity benchmark isn’t intended to measure risk-adjusted results. It instead assesses how its investment team has done by measuring results against a mix of private equity indexes (see page 18, Appendix 2, Part B).

However, North Carolina issue its latest investment report within days of when CalPERS released its CIO investment report. That doesn’t necessarily mean the private equity measurement periods match up exactly. But the flip side is that CalPERS’ private equity benchmark has a 1/3 foreign stock component. 5 Given that the US has been in a strong dollar environment, it’s likely that an all-US benchmark that most public pension funds would use would result in a higher return target. So it’t not unreasonable to use CalPERS’ benchmark as a crude proxy.

Remember that Primack cites North Carolina’s supposedly superior private equity (and real estate) results to justify his “don’t touch that dial” position. Over the last three years, the CalPERS private equity benchmark was 10.22%. North Carolina’s private equity returns for that time frame fell short at 9.70%. For the last five years, the CalPERS private equity benchmark was 16.38% while North Carolina earned only 9.30%.

As more people look under private equity’s hood, the more it becomes obvious that its defenders have only a short list of tired talking points that don’t hold up well to scrutiny. Given that there are many people who make a handsome living from the crumbs that fall off private equity plates, it’s encouraging to see such a powerful industry get a tad defensive.

____

1 One concern is that the study was funded in part by the Laura and John Arnold Foundation, which is rabidly hostile to public pension funds. However, the report is judicious and looks analytically solid. Even though someone from the Arnold Foundation was among the reviewers, there more people with public pension fund and private equity experience providing input.

Nevertheless, statements like this, while technically accurate, are frustrating:

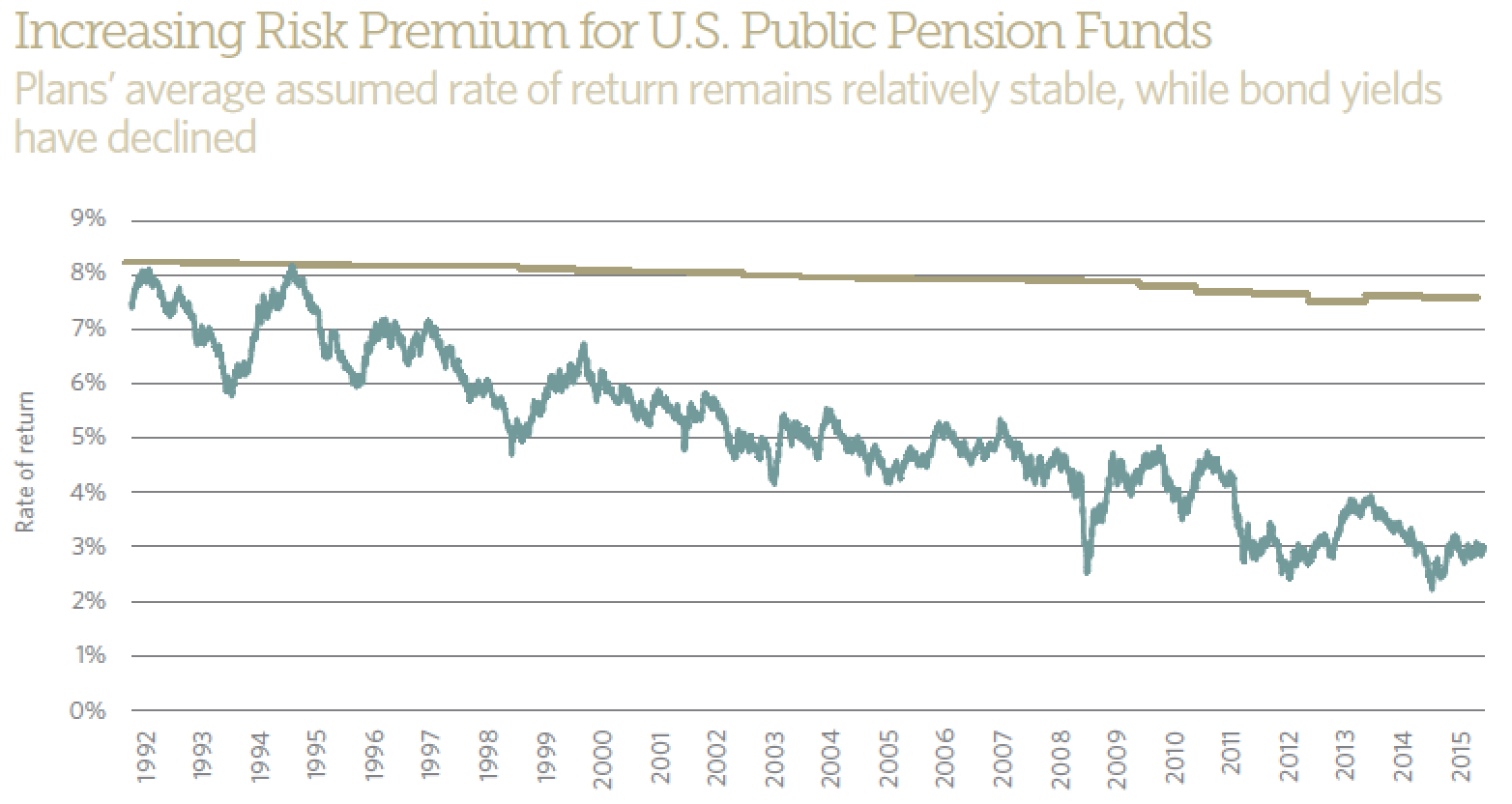

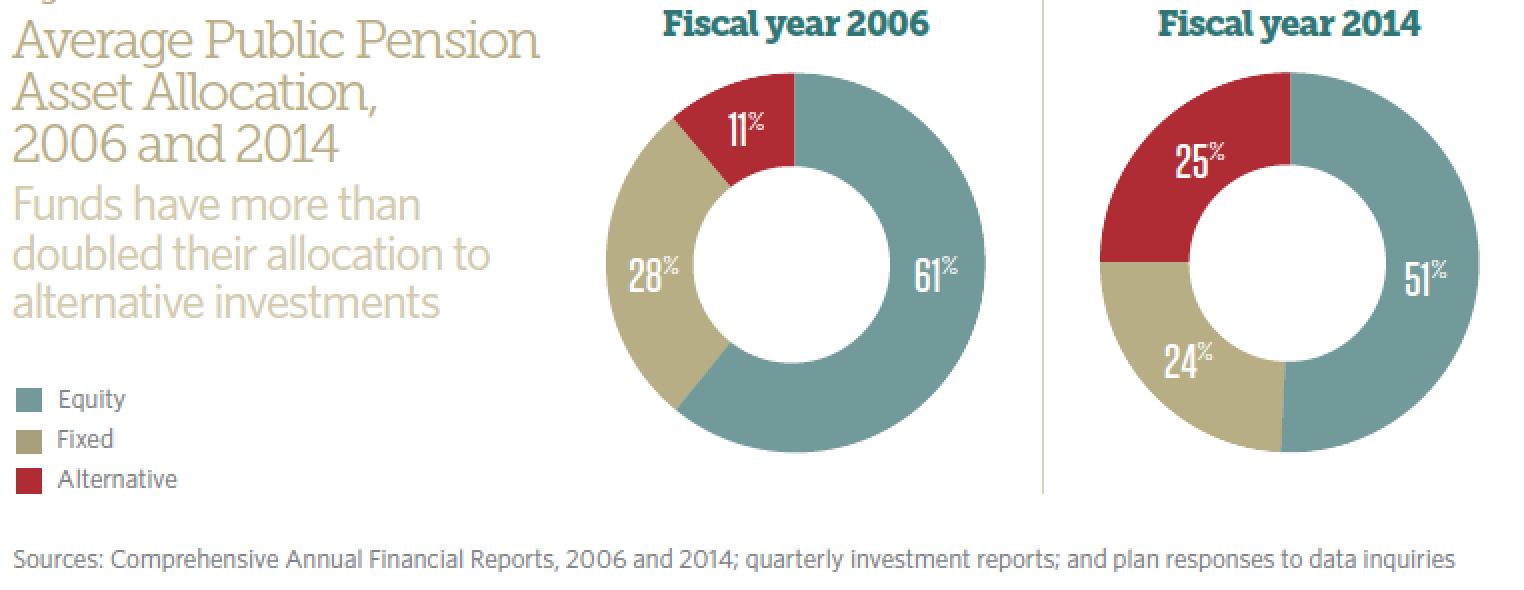

In a bid to boost investment returns and diversify investment portfolios, public pension plans in recent decades have shifted funds away from low-risk, xed- income investments such as government and high-grade corporate bonds. During the 1980s and 1990s, plans signi cantly increased their reliance on stocks, also known as equities. And over the past decade, funds have increasingly turned to alternative investments to achieve investment return targets.

We discussed how in 1978, the Department of Labor issued an new interpretation of its rules that allowed pension fund investors to assess risk on a portfolio basis rather than an investment-by-investmetn basis (public pension funds are not required to follow ERISA but virtually all do). That change came about in no small measure as a result of lobbying by the then-in-its-infancy venture capital industry. But it was also seen as being desirable to allow pensions to manage themselves in accordance to modern investment thinking. However, as we detailed in ECONNED, orthodox methods in financial economic understate risk in several significant ways. So following the advice of the experts leads investors to take on more risk than they bargained for. In addition, it is key to remember that public and private pension funds take actions that have been blessed by experts for liability reasons. But complex investments justify higher consultant fees, so it would be against their economic interest to recommend against alternative investments or call for more limited use if their clients wanted to load up.

2 It’s perplexing that the study is based on 2014 data (yes, they say this is the most recent they could get, so I wonder if this is a function of difficulty of extracting information from some of the funds included in their data analysis). I also can’t tell if the report addressed the fact that public pension funds are are June 30 fiscal years but the ones that report detailed private equity fees and costs like CalPERS do so on a calendar basis because that’s how the private equity fund managers report them.

3 A source for our account said he hadn’t spoken to the Journal and thought sources at CalPERS could be relying on our account. But our write up could also have led someone at CalPERS to dig up old board meeting transcripts.

4 It may be that the unexpected departure of the head of private equity, Real Desrochers, led the Journal reporters to go sniffing around for a story and this was the best they could come up with. There seems to be two schools of thought which are not mutually exclusive as to why he left. One is that, as will be presented formally at CalPERS’ board meeting later today, chief investment officer Eliopoulos is proposing to restructure the investment organization and put private equity under global equity investing. That would be tantamount to a demotion for the private equity chief. Desrochers is going to the private equity investing area of the Chinese state bank CIC, which would be risky for anyone but particularly for so a non-Chinese speaker (which I presume is Desrochers’ status). Desrochers is rumored to be particularly money-oriented and this post presumably has the required hazard comp.

5 67% FTSE U.S. Total Market + 33% FTSE All World ex U.S. + 300 basis points.

I love the corruption cycle at the heart of Yale’s defense of PE investments. Future donations must never be imperiled! Universities truly are becoming nothing more than advanced finishing school to establish social connections.

> Our 2016 post discussed at length how the giant public pension fund had considered setting up its own private equity arm in 1999, as some Canadian pension funds have done in recent years.

From this last Saturday’s Globe and Mail in an article titled “Ottawa’s courtship of pension plans is on the rocks”.

Basically, the story goes, Trudeau had a meeting at a Toronto hotel where the boots of Canada’s big pension managers had the leather licked off, to no avail. The pension managers are unmoved and unless the proposed infrastructure bank was run according to their wishes, not one penny would be put in by them.

What do Canada’s big pension funds “invest” in?

The real message to Mr. Trudeau was buried deeper in the release, when Teacher’s CEO Ron Mock spelled out the terms of engagement on the planned bank. He said: “We recommend the government appoint a strong, professional and independent board to ensure it is run like a business, as is the case for Canadian pension plans, which have validated the soundness of this model on the global investment stage”.

Teachers’ and the countries other major pension plans own roads, water systems, airports and other essential infrastructure around the world. The funds enjoy tax exempt status. Their reluctance to invest in domestic projects must drive the Liberals a little nuts. However as Mr Mock said, the ability to invest independent of political interference has created a Canadian pension system that’s the envy of the industrialized world.

Pension plan CEOs are comfortable saying no to requests for capital, even if the caller is as charming as our Prime Minister. Mr Mock, for example, gets endless investment advice from well meaning teachers who want to make the world a better place: No nukes, no smokes, no trans fats. Mr Mock smiles politely, points out that the fund’s only goal is to earn superior risk adjusted returns, and quietly invests in uranium, tobacco and junk food companies, if that’s where he sees value.

None of Canada’s biggest investors – pension plans, banks and insurers – have ruled out backing the Liberal’s infrastructure bank. But it’s clear these institutions are only going to make a commitment on their own terms.

At a news conference in early April when Teacher’s announced it’s financial results, Mr Mock took time to point out that jurisdictions with track records for successfully attracting private capital to infrastructure, such as Britain and Australia, started with an overarching philosophy that these assets should be in private hands, and got sign off on that approach from every level of government – provinces and cities control the bulk of infrastructure assets in this country.

The Liberals can still get their infrastructure off the ground, but to win the hearts and wallets of Canada’s biggest fund managers, Mr. Trudeau is going to let them run this relationship.

Frankly, having pension funds dictate terms isn’t even the tail wagging the dog. It’s the flea on the tail wagging the dog.

The same person, a bankster, that advised the economically ignorant Premier of Ontario, Kathleen Wynn to “privatize” Hydro One is now an adviser to Trudeau, and he is the one pushing this bank as the only way to get infrastructure done. It’s as if how infrastructure was funded in the past has been expunged from our collective memory.

All the big “private” pension funds in Canada are run for the benefit of government employees. People that work in the “private” sector in Canada, that pay the taxes that fund the government employees have no pensions, which is ironic since teachers themselves would fight tooth and nail to avoid becoming privatized themselves.

When Mr Mock has his way with us, his toll booths will be at the end of our driveways. Need to go anywhere? Pay Teachers first. Want to drink a glass of water? Pay Teachers first. Need to go to the bathroom? Pay Teachers first.

The fees that private equity firms charge portfolio companies are uncontainable. The model that PE has setup, and pension funds have endorsed, lead to an enormous amount of asset stripping. This in turn leads to jobs being slashed, company pension obligations disregarded, labor unions dismantled, countless bankruptcies, and the crappyfication of products and services. This is the true cost of PE that often gets ignored and no report can accurately quantify. In principal PE seems like a good idea, investing resources to improve companies, but that almost never happens. The reason it never happens is because to do that a PE firm would need to replicate a Bain consulting or McKinsey, and that would mean hiring thousands of people; this in turn would cause PE owners to share the riches, and that would be crazy.

And here’s a crazy idea for CalPERS and other pension funds. How about you buy companies and hire BCG, McKinsey, Deloitte, or E&Y to perform your operation improvements? Including, change management, group purchasing to reduce costs, find “top shelf” senior advisors, etc etc blah blah blah. In the end, nearly all PE firms hire these same consultants, why not eliminate the middle man? I’ll take my consulting fee at the door :)

And to turn a nice profit, how about if CalPERS sells the companies to CalSTRS for a nice little profit, then CalSTRS sells the same company to OhioSERS for a bit more profit, and then OhioSERS to Florida Investmebt Board for a nice little profits and so on and so on. That is basically what PE firms do. In this way the pension funds can each make a profit at every transaction. Also, pension funds can just add debt to the whole scheme until the economy explodes and Uncle Sam bails everyone out. And occasionally, you can take some companies IPO and really make a killing. With low interests rates the poor saps trying to make return will have no choice but to buy the crappyfied companies and hope they are not the last ones holding the back. I take my consulting fee at the door ;)

an aside:

NC reporting on CalPERS and PE has warned for some time of the growing dangers of public disaffection for the large pensions and Wall St.’s desire to carve them up into fat management-fees-fiefdoms for Wall St companies. The attacks are increasing and coming from different and unrelated entities (who make rather strange bedfellows).

I’m glad the real returns v risk of PE are reaching a wider audience. Here’s hoping pension boards realize the dangers of remaining in a bubble of conventional thinking.

Thanks to NC for continued reporting.

“Among the options being considered are: buying a private-equity firm or creating a separate company outside Calpers that would make private-equity wagers. Calpers could also choose to act as the sole investor in more customized accounts with outside managers, these people said….

In perhaps the biggest shift being reviewed, Calpers also may ask its staff members to make private-equity investments directly.”

Been there, done that, failed spectacularly

How are those Silver Lake and Apollo equity stakes working out for them? I’m sure investing directly would meet the same fate considering their co-investment experience has been radio silent since that became a big push a few years ago.

Finally, “creating a separate company outside Calpers…” ah yes I am sure the SEIU and political hacks would have no qualms about that!

Really poor reporting by thr WSJ

I’ve been off the grid for a couple of days and just saw this post.

It’s very concerning to read in the footnote that the Arnold Family Foundation was a funder of the Pew study, even if they weren’t able to skew it in their habitual anti-pension way. However, it is also of concern that Eliolopoulos has defenestrated Des Rochers and taken over PE at CalPERS, now trumpeting in the WSJ the possibility of hiring an outside firm to manage CalPERS’s PE investing.

This is just the sort of Trojan Horse that John Arnold loves — to hand over the savings of California public servants to unscrupulous and corruptible outsiders. Arnold made his fortune after leaving Enron on a sucker bet with a Canadian teachers pension fund. They lost billions to him, and this is part of why the Canadian pensions started to re-think their investment strategies.

The CalPERS Board should beware of Greeks bearing gifts…