For much of the post-WWII era, the United States maintained a set of institutional boundaries designed to govern the use of military force. War was understood to be exceptional, geographically bounded, legally regulated, and publicly accountable. Intelligence agencies gathered and assessed information. Military forces fought wars under declared authority, subject to the laws of armed conflict. Covert action existed, but as a marginal and politically risky exception rather than a governing mode.

Over the past two decades, those boundaries have steadily eroded in the U.S. The result is not simply a more assertive national security posture, but a transformation in how force itself is authorized, exercised, and justified. War has become increasingly untethered from formal declarations, legal clarity, and public accountability. U.S. recourse to military action has become routinized as a permanent, flexible instrument of policy rather than an exceptional act requiring Congressional approval and legal restraint. This transformation reflects a convergence of growing secrecy, elastic legal authority, and institutional incentives that favor action over restraint.

Venezuela as example

The recent U.S. attack on Venezuela provides a useful illustration of this transformation. Public reporting and official statements have been marked by ambiguity: unclear operational roles, uncertain legal authorities, and a heavy reliance on deniability. Whether any particular operation ultimately proves lawful or unlawful is less important here than the fact that its legal basis, chain of authority, and evaluative framework are unclear by design.

When it is difficult to determine whether an operation falls under military authority, intelligence activity, law enforcement, proxy action, or some hybrid, the distinction between war and non-war has already begun to dissolve. The question is no longer simply what happened, but under which framework it would even be evaluated. The Venezuela attack shows U.S. force projection increasingly operating in gray zones, where secrecy substitutes for accountability and legal boundaries are treated as adjustable.

Armed Reaper drone – CIA asset?

Vanishing norms

Before the attacks of September 11, 2001, U.S. national security institutions operated, at least formally, within more clearly defined roles and constraints. Intelligence agencies focused primarily on collection, analysis, and influence. The military conducted overt operations under Title 10 of the U.S. Code, embedded in chains of command governed by the laws of war. Covert action existed, but it was episodic, politically sensitive, and treated as an exceptional departure from normal practice rather than a standing mode of force.

The post-9/11 environment altered that balance in a more subtle but more consequential way. The 2001 Authorization for Use of Military Force did not openly declare a global or permanent war. Instead, it delegated to the Executive the authority to determine who constituted the enemy, without specifying geographic limits, temporal boundaries, or a mechanism for revisiting those determinations. That delegation, combined with the global framing of counterterrorism, created a durable framework for executive discretion untethered from defined enemies or clearly delimited conflicts.

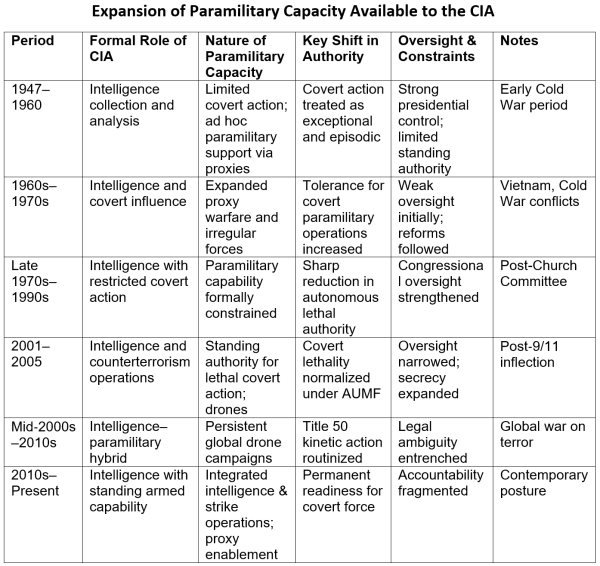

Over time, what began as an emergency response to a specific attack hardened into a standing framework for discretionary force. The Central Intelligence Agency, historically an intelligence and influence organization, acquired persistent access to paramilitary and kinetic capabilities through covert action authorities. Lethal operations that once required extraordinary justification became routinized. Geographic limits faded as the concept of a global battlefield took hold. Temporal limits disappeared as the conflict was treated as ongoing by definition rather than by circumstance.

This transformation was not the product of a single decision or an explicit repudiation of prior norms. It emerged through an accretion of precedents—each legally defensible in isolation, each justified as necessary adaptation, but corrosive in aggregate. As enemy designation, operational scope, and conflict duration migrated from legislative definition to executive determination, the boundary between exceptional wartime authority and ordinary governance steadily eroded.

Title 10 and Title 50 legal authorities

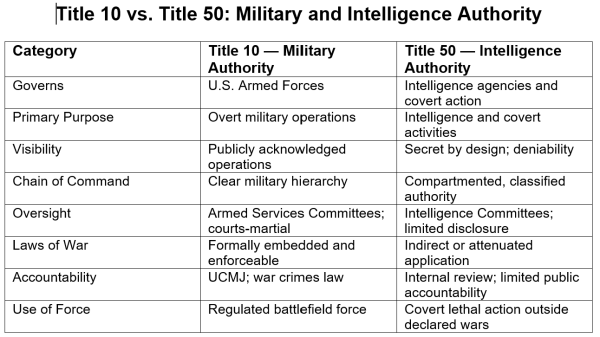

At the heart of this transformation lies in an important distinction between two sections of U.S. statutory law. Title 10 governs the armed forces. It presumes overt military operations, clear chains of command, enforceable rules of engagement, and formal adherence to the laws of armed conflict. Title 50 governs intelligence activities, including covert action, where secrecy and deniability are central by design and oversight is limited to select congressional committees.

The CIA’s founding statute did not envision the agency as an armed or war-fighting institution. Created by the National Security Act of 1947, the CIA was designed as a civilian intelligence organization focused on collection, analysis, and coordination. While the Act allowed the President to direct “other intelligence-related functions,” it assumed a clear separation between intelligence activity and the use of armed force, which remained the province of the military. The later expansion of CIA-directed lethal operations represents not the fulfillment of this design, but a departure from it—one that occurred without including the legal and ethical frameworks that govern warfare.

Both authorities are lawful. The problem arises when lethal force migrates from the Title 10 framework to Title 50 without carrying its normative constraints along with it. Under Title 10, the laws of war are not optional guidelines; they are structurally embedded through training, doctrine, and enforceable accountability. Under Title 50, those same norms are difficult to enforce in practice, even when formally acknowledged. From an operational standpoint, the shift can be subtle. The same personnel may operate in the same regions, using the same weapons, against the same targets. What changes is the legal wrapper—and with it, the mechanisms that make restraint meaningful rather than aspirational.

Converging Institutions

This authority migration has been reinforced by the growing convergence between intelligence agencies, elite special operations forces, and conventional military units. Over the past two decades, operational distinctions have blurred. Intelligence-led missions increasingly resemble military operations. Military units increasingly operate under intelligence authorities.

Elite military formations, such as units operating under Joint Special Operations Command, operate at the intersection of these frameworks. While their personnel are members of the armed forces and trained in the laws of war, their missions may be conducted under covert authorities designed for secrecy rather than battlefield accountability. Oversight fragments as operations shift between Title 10 and Title 50 regimes. The result is a gray zone in which responsibility is diffuse, attribution is contested, and restraint depends less on enforceable rules than on internal discretion.

This institutional convergence produces a greater hazard. When intelligence organizations possess standing kinetic authority, analysis itself is reshaped. Intelligence no longer functions solely to inform decision-makers; it becomes oriented toward enabling action. Evidence is evaluated through the lens of feasibility rather than restraint. Uncertainty becomes a justification for force rather than a reason for caution. Secrecy compounds this distortion. When decisions are insulated from external scrutiny, there is little corrective pressure to distinguish between intelligence assessment and operational advocacy. Even successful operations can degrade decision quality by reinforcing a system in which action validates analysis after the fact.

Erosion of the Laws of War

The laws of armed conflict function only when they are institutionally enforced. They rely on clear combatant status, transparent command responsibility, acceptance of surrender, and after-action accountability. Under Title 10, these requirements are explicit. For example, an order to “take no prisoners” would be unlawful, and U.S. service members are obligated to refuse it.

Covert lethal action undermines this structure not by openly violating the laws of war, but by sidestepping the conditions that make them operative. Intelligence agencies are not organized around battlefield transparency or public accountability. Their governing imperatives—secrecy, deniability, mission success—are fundamentally misaligned with the norms of military conflict. As covert lethality becomes normalized, legal exceptions accumulate. Over time, the exception becomes the rule, and restraint becomes discretionary rather than structural. The danger is not that war crimes are ordered, but that the bright lines preventing them fade from operational relevance.

Erosion of law at home

The implications extend beyond foreign policy. Institutional habits travel. Once normalized abroad, elastic authority, secrecy, and exceptionalism find analogues domestically in government surveillance, policing, and protest control. The boundary between external defense and internal governance weakens, not through conspiracy but through organizational drift. Militarism does not “come home” as a deliberate plan. It arrives as a consequence of government practices allowed to operate without oversight or legal limits.

Conclusion

Venezuela is not an isolated military operation. It is a symptom. The deeper danger lies in a national security system that conducts war outside the rules of war; exercises force without democratic constraint; and treats legal boundaries as adjustable rather than constitutive. Restoring restraint does not require abandoning security; it requires reasserting the institutional distinctions and safeguards that once made restraint enforceable. Without restoring clear distinctions between intelligence activity and war fighting; secrecy and accountability; and authority and legitimacy, the United States risks sliding into a condition of permanent war without boundaries.

Blame it on Truman I say. He was easy prey to that era’s version of the Neocons. Later he said he regretted the CIA but as he was a big Cold warrior in so many other ways we are entitled to doubt his regrets.

Carolinian

Don’t you mean congress at that time?

90 minutes and still no replies. Is everyone speechless?

Like so many essays, this ends with a statement about how things might be in the future. Yet it seems to me this is a state that we are already enduring.

Thank you for this great summary, concise and informative.

I have to be a bit of a pedant and note the US CIA was effectively another branch of the Armed Forces before “9/11”: the CIA bombed the Chinese Embassy (Serbia/Yugoslavia) in 1999 … 25 years before Israel bombed the Iranian Consulate in Syria LOL

= MilitaryWatchMag

= WarOnTheRocks

interesting discussion – ABAbrams – Korea analyst

I would go further as to where things are at operationally today. I would be a bit less generous about past history as well. Much of what happens is now covert. This goes pretty far back, on an occasional basis.

In the early 60s, I recall President Truman had second thoughts about the natl security bill he signed into law, which established a national intelligence agency.

More recently the Pike (house) and Church (senate) committees in the mid 1970s unearthed some of the goings on. The Pike report was published in the UK. It was suppressed domestically though I believe some was leaked to the village voice. My takeaway (as of mid 70s) was that about half the cia budget was for “dark ops” such as assassinations, kidnapping, proxy wars, and the other half was for the analysts and paying informants, and mostly paying for placement of stories in newspapers globally. Most significant periodicals in most if not all countries aligned with the usa would have a cia minder on the payroll helping editors and writers see the correct point of view. The cia probably is still funding communication of the Empires narrative around the world. Thus the importance of blogs such as this.

Deniability became really big after Watergate and especially after Reagan’s Contras were funded – after specifically defunded by Congress – through covert drug running into the usa. Apparently our friend Epstein was in on this op. Drugs and covert ops seems to have been ongoing from the golden triangle of Vietnam era days up to Afghanistan. No doubt still ongoing somewhere.

Over the years there has been virtually no congressional oversight. Many of those members on oversight committees are funded by the MIC. The MIC gets what they pay for!

It is clear to me it is just a matter of time now (that might be optimistic, perhaps time is already up) that the dark ops methods are used domestically. No longer occasionally but constantly.

Thanks. The intro is spot on. As I waded into the meat of it, I couldn’t help but chuckle at all the times the Patriot Act was re-ratified (or whatever you call it). A couple of observations. Abu Ghraib provides an exception to the “each legally defensible” line of thought, which I generally agree with. And, I would consider 9/11 the starting point.

Let’s see, the US Military has murdered more than 100 civilians, committed piracy on the high seas and committed an act of War against Venezuela without even the fig leaf of a Congressional AUMF.

It strikes me that “King” is an inadequate title for Trump, ” Emperor” is more apt.

“Emperor Norton the Second” seems fitting.

I respectfully disagree. I think King and Emperor have way too many grand connotations.

I prefer Dictator and the Trump dictatorship. It pays homage to Trump’s verbal diarrhea, his basing his grab on emergencies and conveys the appropriate connotation of small time nastiness.

Going with the temper of the times I’ll throw in the suggestion that Trump is our Moderne Day “Ubu Roi.”

It is inescapable that today’s American politics have entered the realm of the absurd.

His Effulgent Excellency Ubu Roi: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ubu_Roi

Bow down and make praise, or else!

Merde!

How about Prostetnic Vogon?

I would contend that Trump is just doing what the deep states wants to do. If he went and was replaced with a “nice guy” like Obama was supposed to be, the policies would still be identical no matter who replaced him. Also, if Trump took Greenland and in 2028 the Democrats got back in, does anybody believe that the Democrats would pull the US out of Greenland? (crickets)

I’m not sure the immediate post-WWII era should be viewed as a norm or a deviation from the norm. The law of armed conflict evolved in response to a specific character of war-fighting that perhaps can be seen as a subset of the Clauswitzian construct. As the Supreme Court decided in the Prize Cases, “war” is determined by the facts on the ground. That implies input from the “finder of fact” as to the relevance of evidence.

But it’s probably correct that grey areas create room to exploit nuances in ways that might not be generally intended. I don’t know how you get around that. The NSC/DNI constructs are supposed to bypass the “silo” information/action structures that can enhance grey area maneuvering.

“The CIA’s founding statute (1947) did not envision the agency as an armed or war-fighting institution.”

This is not completely accurate. See, for example, the State Department Policy Planning Memorandum written by George Kennan on May 4,1948. Kennan was then head of this Policy Planning staff. (This Kennan memorandum remained secret until 2005).

It clearly indicates that the CIA was largely created because the State Department wanted dirty deeds done without it being attributed to them.

“Understanding the concept of political warfare, we should also recognize that there are two major types of political warfare-one overt and the other covert. Both, from their basic nature, should be directed and coordinated by the Department of State. Overt operations are, of course, the traditional policy activities of any foreign office enjoying positive leadership, whether or not they are recognized as political warfare. Covert operations are traditional in many European chancelleries but are relatively unfamiliar to this government…It was with all of the foregoing in mind that the Policy Planning Staff began some three months ago a consideration of specific projects in the field of covert operations where they should fit into the structure of this Government, and how the Dept. of State could exercise direction and coordination.”

The article is good but it forgets to mention one thing that I think is worthy of mentioning. That is the USA does have developed over the years a supreme military force especially if we exclude out of consideration China’s recent development and Russia’s nuclear arsenal. With a very very powerful tool at hand the attitude of everyone certainly would change. That is just human nature. When two hundred years ago USA was but one nation among all the other western powers, when half a century ago USA can fail terribly in their special operations in west Asia and later in Somalia, everyone obviously would think again before doing daring things.

The US military is not supreme. It is a shadow of the one that invaded Iraq in 2003. We with our NATO allies have been unable to beat Russia in Ukraine. We could only hit Iran and pretend it was a one and done. The attack on Venezuela was a raid, not a conquest. In the meantime, not only did one of three oil tankers we tried to board get away, but Reuters reports that 11 tankers taking oil to China and other supposedly verboten destinations left Venezuela between January 1 and January 6. So our blockade is a fiction too.

While we’re on it, the Houthis beat the USN.

It would be arrogant to assume that the public cannot distinguish reality from fiction. However, I believe that Hollywood films have influenced the idea that America is above the law, and that the military, intelligence agencies, and law enforcement should be tolerated no matter how extreme their actions are, as long as they’re done in the name of justice.

and there it is…us entertainment business defining justice…. post orwellian perhaps…but nonetheless….here we are

In a fascinating essay on Fred Gao’s Inside China Substack, Professor Zheng Ge of the KoGuan Law School of Shanghai Jiao Tong University sets out how the U.S. has remade the boundary between war and law enforcement through legal interpretation techniques. The whole system of state sovereignty and the equality of states in international law has effectively been subverted through the way that the U.S. has altered and expanded the concept of insurgency. This legal interpretation, Zheng says, “is not a branch of law, but rather a theoretical description of U.S. ‘foreign-related rule of law.’ U.S. domestic law contains many laws targeting other sovereign states and their regions. According to these laws, the legitimate governments of other sovereign states are sometimes labeled as ‘insurgents,’ while at other times rebels in other countries may be designated as ‘insurgents,’ thus revealing that the order disrupted by ‘insurgents’ is not the domestic order of a specific sovereign state, but rather the U.S.-led global order.

“The cunning of this legal logic lies in its creation of a ‘hybrid legal status’: it invokes certain rules of the law of armed conflict to justify the use of lethal force, while applying more flexible law enforcement standards in matters of jurisdiction, detention procedures, and target review,” he continues. “The 2012 revised edition of the U.S. Government Counterinsurgency Guide first blurred the line between ‘counterinsurgency’ and ‘overseas stability operations,’ redefining U.S. military support for foreign governments suppressing ‘insurgencies’ as ‘law enforcement assistance.’ Within this framework, the U.S. does not need to declare war on Venezuela or treat the Maduro government as a belligerent opponent; it only needs to temporarily designate specific individuals as ‘members of international criminal networks’ through the ‘threat assessment’ process in the President’s Daily Brief. Once this legal characterization is completed, the entire operation slips from the framework of international law into the jurisdiction of U.S. domestic criminal law. Maduro is no longer the head of a sovereign state, but a ‘fugitive felon,’ a criminal suspect who can be globally pursued, extradited, and tried in U.S. courts.”

The charges against Maduro relate purely to domestic U.S. criminal law which effectively means that U.S. courts are claiming that “as long as U.S. domestic law defines certain conduct as criminal and determines that such conduct threatens U.S. interests, the U.S. can exercise criminal jurisdiction over anyone anywhere in the world—including sovereign heads of state.” That international law dies in such a legal interpretation is fully explored in the essay which is worth reading in its entirety. At the back of my mind when reading it, however, was the quote attributed to Karl Rove that the U.S. is now an empire which creates reality through its acts and that all that remains for the rest of us is to study that reality – judiciously or otherwise – and await the next act that reconfigures that reality anew. Zheng Ge’s essay might be just another judicious commentary while we await the next reality-making act, whether that’s in Cuba, Iran (again) or Greenland.

Although I have watched the tempurature turned up on that proverbial frog for most of my life, felt the impact of Reagan congressional acts where secrecy was increased resulting in immediate dumbing down of the Scientific American magazine (and many other sources) followed by, numerous hammer strikes and chiseling at the foundations of the constitutional guidlines by the many legislative sessions, further eroded by calls from the “aristocracy of our moneyed corporations” whose only voice is money where our congress has only ear for money.

I had thought that our constitution was to operate upon the consent of the governed and, those so elected were to govern by the will of the governed. I had thought that the saying ‘the means to justify the ends’ that those ‘means’ are deliniated and defined by The Constitution of The USA in order to achieve a clearly stated ‘ends’. I also thought that, the ‘ends’ for which to strive are deliniated within both The Constitution and in the Declaration of Independance. But now, I see an abandonment of any definition or deliniation as to constraining the means. This is to say that no limit is placed upon the means and that any stated ends will justify for example – Human rights violations, suspention of habus corpus, torture….

Of course, I look the naive for the words above.

Also, it seams to me, that the corrupting influence of big money ought to be discussed and debated, that the use of military force or foreign entanglement ought to be brought back more in line with the constitution. Things like the patriot act and DHS ought to operate closer to the origional concept of notice and oversight and be limited in operational (means) drift to outside constitutional limits.

Without well balaced branches the tree of liberty may become so imbalaced as to topple.

…or Canada.

Thanks for the link to Zheng Ge’s enlightening essay – obviously not intended as a prescription for how to respond.

And thanks to Haig Hovaness for a tight expose of the ongoing slide into legal perversion, where the actual thugs (whatever clever name attached to them or Trump) control so much.

Hopefully the rogue state that is now the US can be constrained by those of its people who disagree profoundly with the current perversion of law. If not, given the other extant “thugs” – and the temptation for any country to imitate them – the world is truly racing towards the end of the Anthropocaene.

How to counter the forces most NC readers would fault for the current headlong rush into catastrophe on so many fronts – climatic to political, social to economic. No longer even sure how the outrage could be productively channelled.

And, from Heather Cox Richardson’s Tuesday evening discussion of that day’s events: (I know, but her letter on FB has 72,000 ‘likes’/ ‘angry faces,’ 4.9K comments, and 27,000 ‘shares.’ An immense audience. And many of my friends read her every word.)

“In Venezuela, the U.S. took Maduro and Flores but rather than supporting the actual winner of the 2024 presidential election, Edmundo González, or opposition leader María Corina Machado, the administration left the Maduro government in place, led by former vice president Delcy Rodríguez.

María Luisa Paúl reported in the Washington Post today that in the hours since Maduro’s removal, the Venezuelan government has cracked down on those showing support for the U.S. operation. It detained at least 14 journalists, sent armed gangs into the capital, restricted protests, and arrested citizens who appeared to be “involved in promoting or supporting the armed attack by the United States of America.”

Machado said the government’s actions are “really alarming.”

The ‘government’s actions’ are to crack down on those of its citizens who are showing support for the armed kidnapping of the President, and essential takeover of their nations’ oil resources, by a foreign government. And, apparently, the US should have put Gonzalez or Machado in charge. Which would have negated the ‘evil’ of the kidnapping?

So, as ‘liberal Dems,’ we have to believe:

1) Trump is a bad guy. A given.

2) His actions of kidnapping (or removing, or whatever the NYT allows us to call it) Venezuela’s President and his wife, transporting them to a New York jail where they will stand trial (can you say, “show trial?”), is an action that goes against the sacred ‘rules based order.’ And, so is ‘bad.’

3) But, since Maduro, and by extension, his vice President, Rodriguez, was ‘illegally’ elected, then the Venezuelan government’s crackdowns on people who support the US’ ‘illegal’ actions, are illegal.

I am believing three impossible things before breakfast. Can’t wait for lunch.

It is mildly amusing watching the NY Times trying to reconcile hatred of Trump with slavish support for the imperial war machine.

US becoming Israel then?!