I’ve been quite taken with Thomas Palley’s few but very high quality posts, particularly since they have often made bold, persuasive arguments. Today, however, he does himself a disservice by giving a well written but conventional (among US academic economists) defense of the central bank’s conduct. Note that he deals only with monetary policy (he treats the various new facilities as an extension of that responsibility, rather than as a quasi-nationalization of the banking system) and (save a brief comment at the end) does not address the Fed’s role as banking regulator.

Note that he also presents the two most common lines of attack on Bernanke & Co. Below, we’ll give a third line of criticism of the Fed which we find compelling, namely, that the central bank has mistakenly looked at the US as an economy in isolation as far as monetary policy and macroeconomic performance are concerned. Failure to consider the impact of trade and financial flows has led the central bank to repeatedly adopt overly loose monetary policy.

First, from Palley. Note that the position he calls “American conservative” has also been advocated by senior Japanese officials trying to prevent the US from repeating its mistakes:

Federal Reserve Chairman Ben Bernanke has recently been on the receiving end of significant criticism for recent monetary policy. One critique can be labeled the American conservative critique, and is associated with the Wall Street Journal. The other can be termed the European critique, and is associated with prominent European Economist and Financial Times contributor, Willem Buiter.

Both argue the Fed has engaged in excessive monetary easing, cutting interest rates too much and ignoring the perils of inflation. Their criticisms raise core questions about the conduct of policy that warrant a response.

Brought up on the intellectual ideas of Milton Friedman, American conservatives view inflation as the greatest economic threat and believe control of inflation should be the Fed’s primary job. In their eyes the Bernanke Fed has dangerously ignored emerging inflation dangers, and that policy failure risks a return to the disruptive stagflation of the 1970s.

Rather than cutting interest rates as steeply as the Fed has, American conservatives maintain the proper way to address the financial crisis triggered by the deflating house price bubble is to re-capitalize the financial system….The logic is that foreign investors are sitting on mountains of liquidity, and they can therefore re-capitalize the system without recourse to lower interest rates that supposedly risk a return of ‘70’s style inflation.

The European critique of the Fed is slightly different, and is that the Fed has gone about responding to the financial crisis in the wrong way. The European view is that the crisis constitutes a massive liquidity crisis, and as such the Fed should have responded by making liquidity available without lowering rates. That is the course European Central Bank has taken, holding the line on its policy interest rate but making massive quantities of liquidity available to Euro zone banks.

According to the European critique the Fed should have done the same. Thus, the Fed’s new Term Securities Lending Facility that makes liquidity available to investment banks was the right move. However, there was no need for the accompanying sharp interest rate reductions given the inflation outlook. By lowering rates, the European view asserts the Fed has raised the risks of a return of significantly higher persistent inflation. Additionally, lowering rates in the current setting has damaged the Fed’s anti-inflation credibility and aggravated moral hazard in investing practices.

The problem with the American conservative critique is that inflation today is not what it used to be. 1970s inflation was rooted in a price – wage spiral in which price increases were matched by nominal wage increases. However, that spiral mechanism no longer exists because workers lack the power to protect themselves. The combination of globalization, the erosion of job security, and the evisceration of unions means that workers are unable to force matching wage increases.

The problem with the European critique is it over-looks the scale of the demand shock the U.S. economy has received. Moreover, that demand shock is on-going. Falling house prices and the souring of hundreds of billions of dollars of mortgages has caused the financial crisis. However, in addition, falling house prices have wiped out hundreds of billions of household wealth. That in turn is weakening demand as consumer spending slows in response to lower household wealth.

Countering this negative demand shock is the principal rationale for the Fed’s decision to lower interest rates. Whereas Europe has been impacted by the financial crisis, it has not experienced an equivalent demand shock. That explains the difference in policy responses between the Fed and the European Central Bank, and it explains why the European critique is off mark.

The bottom line is that current criticism of the Bernanke Fed is unjustified. Whereas the Fed was slow to respond to the crisis as it began unfolding in the summer of 2007, it has now caught up and the stance of policy seems right. Liquidity has been made available to the financial system. Low interest rates are countering the demand shock. And the Fed has signaled its awareness of inflationary dangers by speaking to the problem of exchange rates and indicating it may hold off from further rate cuts. The only failing is that is that the Fed has not been imaginative or daring enough in its engagement with financial regulatory reform.

The hope that merely holding off from further rate cuts would be sufficient to defend the dollar (if that can even be done) was dashed today by the sharp fall in the dollar and the $11 per barrel spike in the price of oil. The 0.4% rise in unemployment means the Fed is not raising rates anytime soon, when the belief the Fed would tighten was the basis of recent dollar strength.

More broadly, what bothers me about Palley’s argument is that combating what he calls a demand shock is neither realistic nor desirable. First, labeling it a demand shock is overly dramatic; until today, a large number of economists felt this downturn could be short and shallow because jobs and consumer spending appeared to be holding up well.

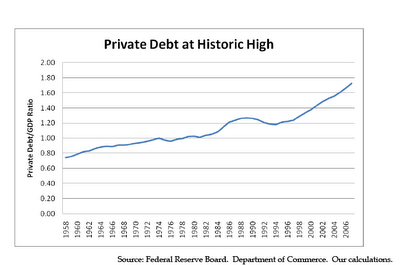

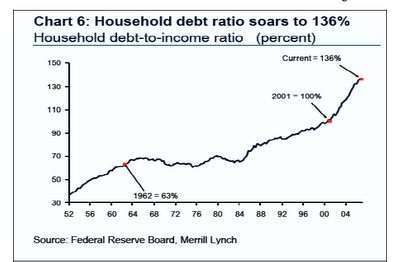

I’ve been in the pessimistic camp because the current level of consumption to GDP (71-72%) is high and unsustainable. It has been achieved only via increasing debt to GDP to unprecedented levels (hence our credit crisis). Charts courtesy Frank Veneroso:

Thus “preventing demand shock” is tantamount to “keeping current levels of demand going” which per above, was accomplished via rising debt levels. We simply cannot keep doing that. The longer we go on, the worse the day of reckoning.

Similarly, the flip side of “consumption is too high” is “savings are too low”, and insufficient savings result in capital influxes which are accompanied by current account deficits. You can debate how the causality runs, but that’s how the math works.

Even with the fall in the dollar, our current account deficit to GDP ratio is over 5%, down from over 6%. That’s all well and good, except a level over 4% leads to a depreciating currency. So again, if you want to defend the dollar, that means more savings (and reducing debt is a form of savings) and less consumption. Thus, lower demand NEEDS to happen; the question isn’t preventing a demand decline (i.e. a recession or prolonged low growth period) but whether and how much the powers that be should intervene to alleviate the pain.

But that sort of reasoning doesn’t go over very well in an America where everyone likes to have their cake and eats it too.

A more respectable, academically rigorous argument comes from Richard Alford, Tim Duy, and Axel Leijonhufvud, who independently have come to broadly similar views. Alford gives a good synopsis:

One of the interesting aspects of economic policy in the US is a belief that we exist independent of the rest of the world. In the minds of many policy makers, the US is the focus and the rest of world economy is just a stable background. To open the model up to external factors, market imperfections, and quasi-floating exchange rates would increase the complexity of the model and limit the number of policy prescriptions that could be made, so most US economists pretend that the rest of the world does not exist, is stable, or that the dollar will quickly adjust so as to maintain US external balances. It has only been in the past few years that the trade deficit has moved to a level that is clearly unsustainable….

If you look at the difference between gross domestic purchases and potential output, by US consumers, businesses, and government — all are above potential output. The only time in recent memory when the difference between these two measures started to narrow was in 2001 when we were in a recession. One of the things we need to consider is that that US may need to see consumption drop significantly before we can achieve a sustainable position, for example vis a vis the dollar…

[T]he demand side is fine. Remember, US domestic purchases are still running around 105-106% of potential domestic output. The problem is not the level of demand but rather the composition of demand. Americans are buying too many imported goods and the world is not buying enough of our exports. So we have a growing wedge growing between gross domestic purchases, which is what the Fed really controls, and net aggregate demand, which is defined as gross domestic purchases less the trade deficit. Given the inability or unwillingness of the US to correct the trade imbalance, the Fed has run expansionary monetary policy almost continuously, generating higher levels of domestic purchases so as to keep net aggregate demand near potential output. The Fed did this using low interest rates, which generated asset bubbles, large increases in consumer debt and sharp declines in savings, and also a larger trade deficit. What has been totally missing is any policy aimed correcting the external imbalance. We are relying on the tools of counter-cyclical domestic demand management to address problems caused by a structural external supply shift..

Tim Duy echoes some of Alford’s themes:

Years of academic research led Bernanke to conclude that the Fed’s best response to the financial crisis is that which should have been deployed during the Great Depression. Fine on paper, but in practice he is using 1930’s monetary policy in the economy of 2008. And that 70+ year gap is exceedingly important in many respects, but perhaps none is more important than the current status of the US Dollar as a reserve currency, a status that allows the US to run a gaping current account deficit. The concern is that the Fed treats the external sector with something of a benign neglect when setting policy, effectively ignoring the reserve currency function of the Dollar. Hence, in a bow to Wall Street, policymakers unwittingly created an overly stimulative environment that feeds back to the US in the form of higher inflation.

Axel Leijonhufvud, in more formal policy paper, makes arguments similar to those of Alford and Duy and makes other pointed observations, such as:

The other lesson to draw from the Japanese experience is that once the credit system had crashed, a central bank policy of low interest rates could not counteract this intertemporal effective demand failure. Year after year after year, the Bank of Japan kept its rate so close to zero as to make no difference, and even so the economy was under steady deflationary pressure and healthy growth did not resume. The low interest policy served as a subsidy that enabled the banks eventually to earn their way back into the black, but this took a very long time.

Contrast this experience with that of Sweden or Finland in the wake of their real estate bubbles (and in Finland’s case the loss of its Soviet Union export markets) in the early 1990s. Both Nordic countries fell into depressions deeper than what they had experienced in the 1930s. Both had to devalue and Sweden in particular had to climb far down from its lofty perch in the world ranking of per capita real income. But, in contrast to the Japanese case, the governments intervened quickly and drastically to clean up the messes in their banking systems (Jonung 2008). Both Sweden and Finland took some three years to overcome the crisis but have shown what is, by European standards, strong growth since. The devaluations that aided their export industries were no doubt of great importance for this growth record but it is extremely unlikely that anything like it could have been achieved without the policy of quarantining and then settling the credit problems resulting from the crash.

We had commented earlier on the experience of the United Kingdom, Sweden. Norway and Finland in the wake of their early 1990s housing crashes. All experienced peak to trough price falls in excess of 25%. All had bad recessions (recessions, mind you, not depressions) and then had strong recoveries once the mess was behind them. Yet for some reason their experience gets short shrift.

I agree with you.

I am surprised by Palley’s defense of Bernanke because Palley has written persuasively about the ill consequences following the Fed’ shift away from concerning itself with wages and jobs toward Greenspan’s passion for equity markets.

Is this simply yet one more example of circle the wagons for one’s colleagues?

The more Benny and the boneheads along with 536 clowns in DC do the worse this will get.

Excellent post. How, pray, does the 3.25 % drop in rates counter the supposed “demand shock”, when credit card rates remain unchanged and elevated, banks lending standards are tightened, re-financing

activity is neutered by falling house prices and larger

down payment percentages, and costs of essentials

continue to rise? Is it the drop in the minimum on my

HELOC from the 1 yr T note? Not much bang for buck.

Yves — I agree with the argument that US demand needs to fall relative to us production, which both means less demand growth and a shift in the composition of demand toward US goods, e.g. a reduction in the trade deficit. However, the argument that any current account deficit above 4% is problematic for a currency seems a bit too strong —

High “carry” currencies (Australia, Turkey) have seen their currencies appreciate even with larger current account deficits.

The US dollar generally has come under pressure if the current account was above 4% of GDP — but there also was a period in the late 90s when the dollar was strengthening in the face of a growing deficit.

Thus, while I would concur that a small current account deficit can be sustained – and the US deficit right now is much larger than the deficit market flows would finance — the argument that 4% is the key level seems a bit too strong.

bsetser

Yves,

A recent speech by John Taylor also supports some of your concerns (pages 9-15). I was surprised that the speech did not get more press as Taylor is a prominent economist and the speech disagrees with the Fed’s mantra. Basically, Taylor is saying the Fed ignored the impact of inflation on other countries with less-than-flexible exchange rates. He also blames commodity prices on Fed policy.

http://www.stanford.edu/~johntayl/Mayekawa%20Lecture%20-%20Taylor.pdf

This is interesting but what’s the policy prescription for shifting demand away from imports?

Higher rather than lower rates? What’s the “unintended consequence” in terms of reduced demand for domestic production?

How do you achieve a sensible shift without creating further havoc when the world operates under such a distorted currency regime? And who’s responsible for that currency regime? Not the US. Not Bernanke.

This is interesting but what’s the policy prescription for shifting demand away from imports?

Some possibilities:

Having a recession.

Putting in a VAT on all goods except necessities like food and simple clothing.

Taxing oil a lot.

Eliminate policies that discourage saving.

The Fed is not bernakes. It is ours:

http://www.TakeBackTheFed.com

Mark

http://www.siv0.com

It’s hard to call Finland’s experience anything but a bona fide depression. GDP dropped by over 10% and unemployment hit nearly 20%. A recession turned into a depression because of stupid exchange rate policies. A floating currency turned out to be the very thing the doctor ordered but two years of wasted opportunity because of politicians worrying about appearances rather than reality.

Finland’s results do not reflect just the housing bust. If you had read the link to the pot I wrote earlier, it said:

According to NATO, Finland had a steeper fall because its contraction was caused by economic overheating, depressed foreign markets, and the dismantling of the barter system between Finland and the former Soviet Union under which Soviet oil and gas had been exchanged for Finnish manufactured goods. Thus its fall in housing prices was more a consequence than a cause of its recession. Sweden similarly suffered from disruption of its trade relationship with the former USSR

Polemics and Inquiries grounded in various points made in the post:

1) As to “re-capitalizing” America’s financial sector: I thought part of the problem had been the “over-capitalization” of the finance sector to begin with; that with $72 trillion of capital planet wide looking for investment opportunties, too much of it had come to America, and so Americans on Wall Street concocted what became, eventually, the NINO mortgage industry to find a place to park all that capital. So maybe getting capital per se isn’t the problem; it’s the line of people standing in line claiming future material benefits in exchange for paper that entitles one to claim material benefits in the now for use to make more of those material benefits in the future….

2. I get the point re: cutting consumption. What I don’t get is the abstraction of it. The matter does become, I fear, somewhat personal, as the fact is: a minority of us have lived much much much better than the majority of us, and that standard of living often is correlated to being rightly connected to the very class of people who helped put us in the predicament we’re in. I very much appreciate the truth that as a general rule, the typical American lives better than billions, literally billions, of people on Planet Earth. It is also true that the typical American has little to say about how or why that is. So when I am told that we need to cut our consumption, I have to consider what, in particular that means: I already have no intention of replacing either vehicle, both American made, the newest of which is already six years old; the last major electronic appliance purchase is the computer I am using right now, and it is going on 5 years old. (It goes without saying, but I’ll say it, that we didn’t chose to move industrial production overseas, we don’t control capital like that.) The temperature is in the 90’s, the humidity is high, but we still haven’t kicked on the central air (we sometimes make it till the end of June.) We’ve even been serious gardeners long before Michael Pollard started to make it fashionable. One of us has been on an airplane in the last 20 years… and I could go on. So whose consumption, exactly, is to be cut, and what are they going to have to give up? (I wanted increases in CAFE standards a decade ago, but what do I care for a “free market”? Personally, I won’t believe that the price of gas is too high for a majority of us until I see the majority of drivers around me adhering to the speed limit. Most people here in the middle of flyover country seem to treat the posted limit as a suggestion…)

3. No, we are not isolated. The capitalist class is an international class, and the capitalist does what it can for its benefit without regard to national boundaries.

1970s inflation was a ‘price-wage spiral’ even as, from 1972-73, wages for production and nonsupervisory personel were held down relative to rate of inflation?

Yes, at least initially, wage rigidity may have contributed, but implying this to have been primary is, I believe, a misunderstanding of that decade’s conjuncture which was also one of crises induced pressure on working class and wages. Capitalism’s postwar golden age could not be perpetuated through the use of political Keynesianism anymore than neo-liberal ‘free market’ policies have brought that age’s restoration.

A month or two ago, Andrew Samwick posted what I believe he called the saddest chart he had ever seen, real weekly and hourly wages, 1964-2008 in 2008 dollars:

http://picasaweb.google.com/lh/viewPhoto?uname=asamwick&aid=5195760215722236945&iid=5200404157632314674

Dave Raithel,

In its 1974 annual report, the Minneapolis Fed noted:

…we are going to have to accept as fact that we cannot continue to expand consumption (i.e., living standards) as rapidly in the next few years as we have during the past decade. It is important to understand that this conclusion rests basically on the argument that credit-financed expansion, beyond a certain point, leads to instability rather than further expansion. The conclusion does not rest on the dubious premise that the world is running out of resources. …

In the past, widespread increases in standards of living in developed countries eased social tensions that otherwise might have been associated with disparities of income and wealth, both within and between countries. If long-nourished expectations of “a better life” (i.e., more goods, services, leisure, etc.) are now going to be frustrated, or at least postponed, as seems inevitable, then there is going to have to be an equitable sharing of the burden of this adjustment.

(1974 Annual Report Essay, The Limping Giant..)

‘equitable sharing’ and reality-for-most; what a divergence.

“One critique can be labeled the American conservative critique, and is associated with the Wall Street Journal. The other can be termed the European critique, and is associated with prominent European Economist and Financial Times contributor, Willem Buiter.

The argument against Paullrey’s assertion has nothing to do with the wall street journal. He is a quack and that is all.The argument against his philosophy is that he is clueless.

What if the gobal warming argument was subjectted to the same scrutiny.

The winter of economic thougt continues.