Charles Wyplosz has a post up at VoxEU that is both clever and informative. He looks at the wisdom of having taxpayers shore up faltering banking systems, using the largely opposed viewpoints of two well-known economists as a point of departure: Larry Summers, former Treasury Secretary, who has argued that intervention is necessary to prevent a slowdown, versus Willem Buiter, a professor at the London School of Economics who has formerly held a number of policy positions, who takes moral hazard seriously and has been very critical of the Fed.

From VoxEU:

Should taxpayers bail out the banking system? One of the world’s leading international macroeconomists contrasts the Larry Summers “don’t-scare-off-the-investors” pro-bailout view with the Willem Buiter “they-ran-into-a wall-with-eyes-wide-open” anti-bailout view. He concludes that either way, taxpayers are always the losers. The best policy makers can do is to be merciless with shareholders and gentle with bank customers.

An old and familiar debate is back. Should taxpayers bail out the US banking system, quite possibly the British and European ones as well?

There are two standard views on the multi-trillion dollar question of who pays for getting us out of the financial crisis.

· One view is that the situation has become so desperate that ordinary citizens will in any case be paying a high price for the crisis; throwing money at banks right now might lower the overall burden by preventing a deep, protracted recession.

· The other view is that banks ought to be left hanging to pay for their sins. Governments ought to be worried about their taxpayers, not bank shareholders.

In fact, we don’t have that much choice.

Too big to fail: the Bagehot rule

It has long been a poorly hidden secret that large banks cannot be left to go bankrupt. Walter Bagehot, a 19th century economist and editor of The Economist, designed the solution that remains as relevant today as it was then. The Bagehot rule is that the central bank ought to lend freely to a failing bank, against high-quality collateral and at a punitive rate (see Xavier Vives’ Vox column).

The modern version of the rule adds that shareholders ought to bear serious costs and the managers ought to be promptly replaced. This is exactly what happened with Bear Stearns last March, where another bank, JP Morgan, was used as the conduit for the operation. The cost to the taxpayers was a $1 billion guarantee and a $29 billion loan to JP Morgan guaranteed by Bear Stearns assets. We don’t yet know if this was a taxpayer-financed bailout. If JP Morgan redresses the situation within ten years, the taxpayers will make a profit. If not, US taxpayers will have borne the burden. Bear Stearns shareholders were almost completely expropriated.

As the US economy keeps limping and the housing market deteriorates, most observers believe that there will be many more bank failures. Indeed, in early July, a large Californian mortgage lender, IndyMac, went belly up and was also subjected to Bagehot’s recipe. The possibility that some very large financial institutions, and many smaller ones, will follow provides urgency for the current debate.

The Larry Summers school of thought: Don’t scare off the investors

One school of thought – let’s call it, fairly I think, the Larry Summers School – is that the Fed has been far too tough with Bear Stearns. It has scared investors and managers alike. The result is that investors are now unwilling to provide much needed cash to banks that must rebuild their badly depleted balance sheets while bank managers strenuously resist acknowledging their losses and continue selling their toxic assets. As a result, the whole banking system is in a state of virtual paralysis, which means that borrowing is both difficult and costly.

Lowering the interest rate, as the Fed vigorously did, does not even begin to redress the situation. This all leads to a vicious circle where insufficient credit drags the economy down, which leads to more loan delinquencies, which further impair banks ability to lend. Memories of 1929 immediately come to mind, when the Fed made matters considerably worse by clinging to financial orthodoxy.

This school of thought fears that the same fascination with high-minded principles turns a bad crisis into another nightmare of historical proportions. The Larry Summers School wants the Fed to lend freely and more generously with the goal being to reassure potential investors. If that is done, so goes the argument, banks will be able to rebuild their balance sheets and resume their normal activities. This would signal the end of the now 1one-year old financial crisis as a virtuous circle unfolds – more loans, a resumption of growth and the end of the housing market decline, healthier banks, and more loans.

The Willem Buiter school of thought: They ran into a wall with eyes wide- open

The other school of thought – let’s call it, a bit unfairly, the Willem Buiter School – sees things in the exact opposite way.

The crisis is the result of financial follies by financial institutions that bought huge amounts of products that they did not understand – the infamous mortgage-backed securities and their derivatives – parked them off-balance-sheet to avoid regulation, and made huge profits in doing so. In short, they ran into a wall with wide-open eyes.Once the all-too-well foreseen crisis erupted, these institutions kept hiding the extent of their losses as long as they could – they are still playing that game – and started to lobby for a bailout from their governments.

The classic credit cycle: Look who’s crying now

This school notes that the crisis is part of a classic credit cycle that involves excessive risk-taking in good times and ends up in tears. The question is: whose tears?

The challenge is ensure that these are not the taxpayers’ tears. Indeed banks are in a unique position. They used to call for a bailout to protect their depositors, but deposits are now insured in all developed countries. Still, because bank credit is the bloodline of the economy, we cannot let our banking system sink. But once banks know that they can play the high-risk, high-return game, pocket the profits, and let taxpayers face the risks, bailouts provide a temporary relief but set the ground for the next crisis.

Wilder and wilder parties

Bank of England Governor Mervyn King nicely sums up the situation: “’If banks feel they must keep on dancing while the music is playing and that at the end of the party the central bank will make sure everyone gets home safely, then over time, the parties will become wilder and wilder.” Bagehot principles can be applied when one or two banks fail, but when the whole system is under threat, this is no longer an option.

Which school is winning with policy makers?

Both schools have developed consistent views. The dismaying part of the story is that they lead to radically different policy implications.

So far, the monetary authorities have been closer to the Willem Buiter School view, but things may be changing. The most recent bailout of Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac is clearly a soft rescue operation, with no set limits and, so far at least, no penalty on shareholders and managers. Even though Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac are very special institutions with a federal mandate, the Larry Summers School is right to see some glimmers of hope and therefore must be taken seriously.

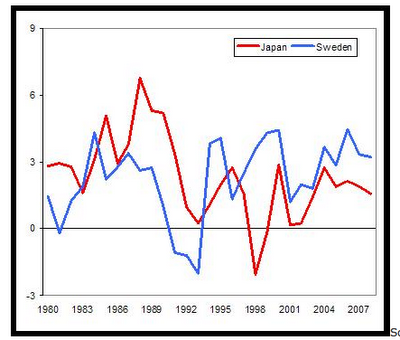

In most respects, we have gone through a very classic credit boom- and bust cycle. Two cases from the 1990s are worth pondering.

· Following years of fast bank credit growth accompanied, as should be, by housing price bubbles, bank crises started in 1990 in both Japan and Sweden. The Swedish authorities reacted swiftly, bailing out most banks at a cost to taxpayers estimated at some 4% of GDP, but shareholders were essentially expropriated.

· The Japanese authorities protected their banks with generous loans, even as some banks were serving dividend payments to their shareholders.

Sweden recovered in three years and, nowadays, Swedish banks are not found among those that indulged in mortgage-backed securities. Japan has still not recovered from a nearly twenty-year long “lost decade” and, nowadays, several Japanese banks have already failed under the weight of the toxic assets that they acquired, once again.

Figure 1: GDP Growth in Japan and Sweden

Source: Economic Outlook, OECDConclusions

Of course, there is more to it than this simple comparison, including the accompanying macroeconomic policies. But three unmistakable messages emerge.1) Be merciless with shareholders and gentle to bank customers.

2) Either way, taxpayers are always the losers.

3) Bagehot had it all right.

I’d go one step further perhaps. Be merciless with stakeholders, and not just shareholders. That includes employees earning large bonuses and bondholders.

We don’t yet know if this was a taxpayer-financed bailout.

We don’t? Why was a guarantee necessary for some BSC assets then? As I recall, at the time it was reported that this was crucial — meaning absolutely necessary from JPM’s point of view — to the deal.

Also, if it isn’t a “taxpayer-financed bailout”, and since the risk nominally resides on the Fed’s balance sheet, I’d be interested in the average person’s reaction to the news — and to most of them it will be news — that the Federal Reserve Bank (funny name), which is so talked about and seems to have a HUGE influence on the economic health of the US — is in reality a private institution. Which it is of course.

“We don’t yet know if this was a taxpayer-financed bailout.”

Absolutely we don’t yet know. The same holds for Fannie and Freddie.

The notion that losses are certain at this point is the big lie in all of this. It’s an agenda driven lie.

[The Fed] is in reality a private institution.

And we know this because, like all private institutions, its governing body is appointed by the President of the United States.

Yves:

You said, “Even though Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac are very special institutions with a federal mandate, the Larry Summers School is right to see some glimmers of hope and therefore must be taken seriously.”

Sorry…I’m confused by your article. In one breath you seem to argue for the Bagehot rule (e.g., shareholders ought to bear serious costs and the managers ought to be promptly replaced) but this appears to me to be the exact opposite of the Freddie/Fannie rescue operation. Indeed the proposal seems to favor privatizing the profits and socializing the losses. So where is the discussion on replacing the execs, freezing bonuses, higher rates, etc? What am I missing here?

“So far, the monetary authorities have been closer to the Willem Buiter School view, but things may be changing.”

You’re kidding, right? The Bear Stearns rescue would have stunned Walter Bagehot. Bear Stearns was not a banking institution; not a member of the Federal Reserve; not statutorily entitled to any protection.

Indeed, it’s always been understood that investment bankers are on their own, earning outsized profits in return for taking outsized risks. The British government, for instance, didn’t step in to protect Barings when Nick Leeson blew it out.

The Bernanke/Paulson government-sponsored bailout of Bear Stearns represents a horrendous precedent, particularly since Bear Stearns was very active in issuing the toxic mortgage securities which destabilized banks worldwide. Not merely closing down Bear Stearns, but hanging its principals in Battery Park would have been a salutary move ‘pour decourager les autres.’

One interesting point to make. Few care about rapid valuation changes on the upside. But people are extremely agitated by rapid value changes on the downside. Now it is obvious why that is. But what is often not addressed is what are the economic costs of failing to allow a collapse to proceed. And much more interesting. What is the economic significance of the fact that collapses can occur with stunning rapidity? What does that tell us about the nature of the allocation of resources? What are the costs of failing to allow a collapse to proceed with the furious, volcanic, rapidity of which it is capable?

FYI, the quotes attributed in comments to me actually came from Wyplosz.

I agree with “a”, above; the costs should be borne primarily by the stakeholders, including management and bondholders. Management should have salaries reduced, bonuses stripped, and unvested compensation emptied out. Bondholders should take a haircut. If leaving the bank in business is the best option, fine, but everyone who benefited from the risk-taking should be paying a price, primarily shareholders and management, but also bondholders.

While Wyplosz’s article seems to imply that this is a balanced argument between two equally rational and reasonabe approaches, the reality is that it isn’t even close. Summers is off the wall, and quite frankly, would fail any Econ 101 class in a junior college much less the august halls of Harvard for his recommendations.

1) I’m annoyed by the phrase “expropriation” of the shareholders. Expropriation is the implication that someone takes something of value from you by force. The govt. isn’t taking anything from shareholders. They’re merely letting shareholders lose their money in a venture that they themselves invested in. Last I checked, BSC’s shareholders didn’t have to write a check for the value of their shares to the Federal govt. The use of the term expropriation automatically implies that the govt. has some sort of obligation to preserve shareholder valuation that it clearly does not. Indeed, if anyone will be expropriated, it will be taxpayers, who will be forced to write a check to the govt to clean up this mess.

2) Both schools have developed consistent views. Consistency doesn’t imply accuracy in modelling reality. Lunatic paranoids can build surprisingly consistent models of their world using selective emphasis of different facts / theories. It doesn’t mean their worldviews should be accepted.

3) The Fed has been of the Buiter school??? Please tell that to Mr. Buiter who’s been excoriating the Fed on a near weekly basis. The sum total effect of the Fed’s actions for the past 18 months has been to delay the inevitable bankruptcy of the U.S. financial sector at the expense of the dollar, inflation, government debt, and its own balance sheet, while creating vast new moral hazards and federal obligations / guarantees without any appropriate regulation that would prevent an even “wilder” party in a decade or so (if recent past cycles replay). I wish my parents punished me as “strictly” as the Fed has punished the financial sector.

4) Still, because bank credit is the bloodline of the economy, we cannot let our banking system sink. Yes, our economy needs credit. But we’re talking about all the CDOs, MBS, etc, etc, that are tanking. Do we really need all of them? And while we need a banking system, do we need the companies and banks that we have now? Or would we be better served by new players / industries? If Citibank is allowed to fail, then whatever services they provided that had value would surely be provided by other firms who’d rise to supply a need. Why bail out Citi?

Similarly, those people who argue that the GSEs should be allowed to fail don’t argue that we don’t need mortgages. Just that the GSEs are not the best way to serve that market.

This is a strawman argument, as no one, not even Buiter, is arguing that we don’t need a banking system. Just that the current banks don’t need to survive in order for the system to serve its vital functions.

5) Either way, taxpayers are always the losers. This line is always trotted out by supporters of the Summers school, who like to imply that if the taxpayers are going to lose regardless, then why don’t we just spend $1 trillion bailing out Wall St.? That money is good as gone anyway, so what does it matter?

But this is an intellectually dishonest way of phrasing it. Of course taxpayers lose. The real point however, is how much do taxpayers lose, and what do they get for it? Wyplosz’ analysis of Sweden vs Japan shows why. Sweden spent 4% of its GDP and was back on track in 3 years. Furthermore, as a result of the shareholders losing their investments, their banks were much more cautious, and the taxpayers won’t have to spend a dime bailing out their banks this turn around.

Japan has lost 20 years with no end in sight as their banking sector takes their lumps from the current downturn as well.

Which country’s actions have caused their respective taxpayers to lose more? That is the real question.

At any rate, it’s a real testament to the weakness of the Summers’ school of thought that despite all the pro-Summers biases inherent in this article, Wyplosz is still forced to conclude that the Buiter school is the better course of action.

Or, more fundamentally, ask the obvious question: Why have privately-owned banks at all?

Fractional-reserve banking is a criminal sham that meets the legal definition of embezzlement.

They should be outlawed and the government should issue debt-free fiat currency (as the Social Credit movement advocated years ago).

This ridiculous fraud kills people and whole economies. We are seeing it right now. Tinkering around the edges will solve nothing.

OUTLAW FRB.

To a: Aye-aye.