By Rob Parenteau, CFA, sole proprietor of MacroStrategy Edge, editor of The Richebacher Letter, and a research associate of The Levy Economics Institute

Reader note: please see yesterday’s post for a discussion of the fiscal balances map.

As evident from the financial balances map, there are a whole range of possible combinations of current account and domestic private sector financial balances which could be consistent with the 7% of GDP reduction in Spain’s fiscal deficit. But the simple yet still widely unrecognized reality is as follows: both the public sector and the domestic private sector cannot deleverage at the same time unless Spain produces a nearly unimaginable trade surplus – unimaginable especially since Spain will not be the only country in Europe trying to pull this transition off.

As an admittedly rough exercise, we can assume each of the peripheral nations will be constrained to achieving a fiscal deficit that does not exceed 3% of GDP in three years time. In addition, we will assume each nation finds some way to improve its current account imbalances by 2% of GDP over the same interval. What, then, are the upper limits implied for domestic private sector financial balances as a share of GDP for each nation?

Greece and Portugal appear most at risk of facing deeper private sector deficit spending under the above scenario, while Spain comes very close to joining them. But that obscures another point which is worth emphasizing. With the exception of Italy, this scenario implies declines in private sector balances as a share of GDP ranging from 3% in Portugal to nearly 9% in Ireland.

Private sectors agents only tend to voluntarily target lower financial balances in the midst of asset bubbles, when, for example home prices boom and gross personal saving rates fall. Alternatively, during profit booms, firms issue debt and reinvest well in excess of their retained earnings in order take advantage of an unusually large gap between the cost of capital and the expected return on capital. We have no compelling reasons to believe either of these conditions is immediately on the horizon.

The above conclusion regarding the need for a substantial trade balance swing flows in a straightforward fashion from the financial balance approach, and yet it is obviously being widely ignored, because the issue of fiscal retrenchment is being discussed as if it had no influence on the other sector financial balances. This is unmitigated nonsense. It is even more retrograde than primitive tales of “twin deficits” (fiscal deficits are nearly guaranteed to produce offsetting current account deficits) or Ricardian Equivalence stories (fiscal deficits are nearly guaranteed to produce offsetting domestic private sector surpluses) mainstream economists have been force feeing us for the past three decades. Both of these stories reveal an incomplete understanding of the financial balance framework – or at best, one requiring highly restrictive (and therefore highly unrealistic) assumptions.

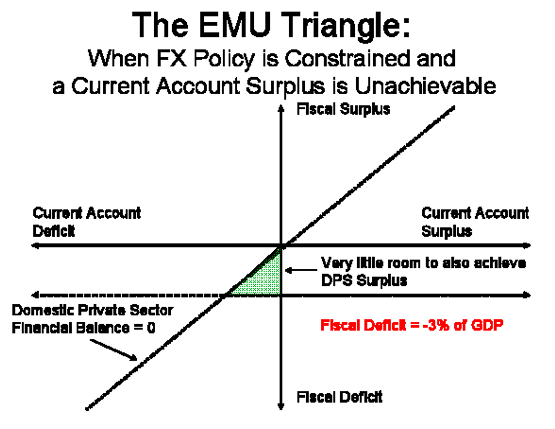

The EMU Triangle

This observation is especially relevant in the Eurozone, as the combination of the policy constraints that were designed into the EMU, plus the weak trade positions many peripheral nations have managed to achieve, have literally backed these countries into a corner. To illustrate the nature of their conundrum, consider the following application of the financial balances map.

First, a constraint on fiscal deficits to 3% of GDP can be represented as a line running parallel to and below the horizontal axis. Under Stability and Growth Pact rules, we must define all combinations of sector financial balance in the region below this line as inadmissible. Second, since current account deficits as a share of GDP in the peripheral nations are running anywhere from near 2% in Ireland to over 10% in Portugal, and changes in nominal exchange rates are ruled out by virtue of the currency union, we can provisionally assume a return to current account surpluses in these nations is at best a bit of a stretch. This eliminates the financial balance combinations available in the right hand half of the map.

If peripheral European nations wish to avoid higher private sector deficit spending – and realistically, for most of the peripheral countries, the question is whether private sectors can be induced to take on more debt anytime soon, and whether banks and other creditors will be willing to lend more to the private sector following a rash of burst housing bubbles, and a severe recession that is not quite over – then there is a very small triangle that captures the range of feasible solutions for these nations on the financial balance map.

It is the height of folly to expect peripheral Eurozone nations to sail their way into the EMU triangle under even the most masterful of policy efforts or price signals. More likely, since reducing trade deficits is likely to prove very challenging (Asia is still reliant on export led growth, while US consumer spending growth is still tentative), the peripheral nations in the Eurozone will find themselves floating somewhere out to the northwest of the EMU triangle. The sharper their fiscal retrenchments, the faster their private sectors will run up their debt to income ratios.

Alternatively, if households and businesses in the peripheral nations stubbornly defend their current net saving positions, the attempt at fiscal retrenchment will be thwarted by a deflationary drop in nominal GDP. Demands to redouble the tax hikes and public expenditure cuts to achieve a 3% of GDP fiscal deficit target will then arise. Private debt distress will also escalate as tax hikes and government expenditure cuts the net flow of income to the private sector. Call it the paradox of public thrift.

As it turns out, pursuing fiscal sustainability as it is currently defined will in all likelihood just lead many nations to further private sector debt destabilization. European economic growth will prove extremely difficult to achieve if the current fiscal “sustainability” plans are carried out. Realistically, policy makers are courting a situation in the region that will beget higher private debt defaults in the quest to reduce the risk of public debt defaults through fiscal retrenchment. European banks, which remain some of the most leveraged banks, will experience higher loan losses, and rating downgrades for banks will substitute for (or more likely accompany) rating downgrades for government debt. A fairly myopic version of fiscal sustainability will be bought at the price of a larger financial instability.

Summary and Conclusions

These types of tradeoffs are opaque now because the fiscal balance is being treated in isolation. Implicit choices have to be forced out into the open and coolly considered by both investors and policy makers. It is not out of the question that fiscal rectitude at this juncture could place the private sectors of a number of nations on a debt deflation path – the very outcome policy makers were frantically attempting to prevent but a year ago.

There may be ways to thread the needle – Domingo Cavallo’s recent proposal to pursue a “fiscal devaluation” by switching the tax burden in Greece away from labor related costs like social security taxes to a higher VAT could be one way to effectively increase competitiveness without enforcing wage deflation. But these more comprehensive solutions, where financial stability, not just fiscal sustainability, is the primary objective, will not even be brought to light unless policy makers and investors begin to think coherently about how financial balances interact.

Or to put it more bluntly, if European countries try to return to 3% fiscal deficits by 2012, as many of them are now pledging, unless the euro devalues enough, then either a) the domestic private sector will have to adopt a deficit spending trajectory, or b) nominal private income will deflate, and Irving Fisher’s paradox will apply (as in the very attempt to pay down debt leads to more indebtedness), thwarting the ability of policy makers to achieve fiscal targets. In the case of Spain, with large private debt/income ratios, this is an especially critical issue.

The underlying principle flows from the financial balance approach: the domestic private sector and the government sector cannot both deleverage at the same time unless a trade surplus can be achieved and sustained. We remain hard pressed to identify which nations or regions of the remainder of the world are prepared to become consistently larger net importers of Europe’s tradable products. Pray there is life on Mars that consumes olives, red wine, and Guinness beer.

Thanks for these two posts that help bring focus on the essentials.

Sweden’s decision to not adopt the euro was preceded by discussions along the lines you raise. The recommendation from the academics in Sweden at the time not not a firm NO but wait and see how it would work out (“will the thing fly despite the design flaws?”)

We are about to find out.

I think you’re missing the fact that Spain has a very specific pattern when it comes to international money flows. Spain receives waves of affluent immigrants from northern Europe (like Florida does in the USA). These new residents will buy stuff from their old countries, on paper generating a spanish trade deficit.

As house prices drop in Spain, another wave of affluent new residents will arrive (and the current very harsh winter in northern Europe will also help). These people will buy vacant properties from developers with stretched balance sheets without replacing the developer’s mortage with a new mortgage of the same size. In this way, private sector deleverating will happen in Spain, even if the public sector deleverages at the same time, and nothing is happening to the trade balance.

I partly agree. Immigration is a huge phenomenon in Spain, with population going up from 39m to 47m in just a decade. Those 8m people mainly came from poor countries (Ecuador, Romania, Marocco) and need to get in debt as soon as they get here (e.g. they buy a small apartment, let’s oversimplify, with German finance and German imports).

But those immigrants are “productive resources”, so that housing, that German finance and those German imports end up being productive investment, increase GDP, improve demographic trends and increase labour-market mobility and flexibility. A saying among Spanish economists, sometimes mistaken as a joke by foreigners, goes: “Immigration equals labour-market reform”.

I cannot see the author has taken into consideration any of the reasoning failures that were pointed out yesterday.

First

During the bubble, Spanish unit labour costs exploded while Germany entered an internal devaluation. This restored German competitivity and rendered some Spanish products uncompetitive.

Krugman illustrated it here: http://krugman.blogs.nytimes.com/2010/02/06/spains-problem-illustrated/

However, Krugman’s graph didn’t consider the different development in the non-tradable sector (e.g. housing-related manufacturing), where salaries exploded, and the tradable sector (e.g. cars), where salaries didn’t explode at all.

Moreover, Krugman compared Spain to Germany only; but it’s Germany the “defective” nation. Any other eurozone nation had a similar unit labour costs (ULC) development vs. Germany.

If you compared Spain to the eurozone, we “only” had a 10% excess increase in ULC over the last decade. However, this increase was mainly related to non-tradable activities; last year, Spanish ULC went down 2% while eurozone ULC went up 3%.

Hence, the original sin, Spanish excess increase in ULC, was reduce by half in just a single year!!!!

http://blogs.cincodias.com/el_economista_observador/2010/02/el-mito-de-la-competitividad.html

Second

The author still fails to acknowledge a very, very simple way to improve the balance account: increase VAT, decrease taxation on local producers (income taxes, company taxes, social-security charges, etc.). This means exporting the problem not only to other eurozone countries, but also to Asia, North America, etc.

Third

Imports from other countries will naturally fall since Greece, Portugal, etc. don’t buy food and clothes from Germany, but premium cars, “factories” (machinery), etc. related to “wealth effects” and long-term investment. Those imports’ fall will be several times higher than the fall in aggregate consumption and investment.

The combined effect of these three unmentioned, important issues renders the analysis as flawed, biased, ignorant and void.

Diego Méndez,

You exhibit an abiding faith in some deus ex machina, e.g. Jesus Christ dying on the cross to win the great struggle between good and evil and save us all from our sins.

You’re not really questioning Parenteau’s underlying analysis. Instead, what you are asserting is that the tradeoffs he says will be necessary can be achieved painlessly. Let’s examine your arguments one by one:

• First: You claim the Unit Labor Cost as reported for Spain is distorted, and making it competitive will be a snap. Competitive labor cost translates to more exports, thus improvements to the current account will be easily and painlessly (that is, requiring no wage deflation) achieved.

• Second: You recommend an increase in VAT and a decrease in taxation on local producers (income taxes, company taxes, social-security charges, etc.), which will export the problem not only to other eurozone countries, but also to Asia, North America, etc.. My understanding of a VAT is that it is a tax placed on manufactured goods. Wouldn’t this make manufactured goods more expensive? And if you make manufactured goods more expensive, doesn’t that make them less competitive in the international marketplace? It seems to me the end result of this would be to diminish exports, thus aggravating the current account balance.

• Third: You assert that the Club Med countries don’t import staples (food and clothes), but luxury goods (premium cars) and machinery. Foregoing these will be easy and painless. Again, this implies that improvements to the current account will be easy and painless.

Again, this all strikes me as a deus ex machina:

A deus ex machina is a plot device whereby a previously intractable problem is suddenly and abruptly solved with a contrived introduction of a new character, ability, or object. It is generally considered to be a poor storytelling technique because it undermines the story’s internal logic.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Deus_ex_machina

In many ways you remind me of Ronald Reagan:

Opinion polls showed that once one got beyond the first superficial questions, people realized it was not possible to lower taxes, vastly increase defense expenditures, and balance the budget all at the same time. But Ronald Reagan was president. He accepted the responsibility. He said what people desperately wanted to hear… When in the 1980 campaign candidate Walter Mondale spoiled the fun by stating that, as president, he would raise taxes because it was the only realistic thing to do, he violated the national mood and threw away whatever chances he had of being elected.

–Daniel Yankelovich, Coming to Public Judgment: Making Democracy Work in a Complex World

Reagan’s deus ex machina was a huge increase in the current account deficit along with massive debt. As the US is painfully learning, Reagan’s demagoguery and wishful thinking may have postponed the day of reckoning, but it didn’t eliminate it.

DownSouth,

my point is the analysis is flawed, since it’s based on the absurd assumption that current account imbalances will improve by 2% in 3 years.

To put things in context, Spain improved its current-account imbalances by over 4% in a single year (2009) with no specific measures taken to improve it. It’s not a dream of mine, it’s not a Deus Ex Machina, it’s what’s been happening last year!!!

But measures can and should be taken to improve even more current-account imbalances. VAT is not a tax on manufactured goods. VAT is a tax on consumption, which taxes locally provided goods and imports (but not exports) at the same rate; all other taxes are applied to locally provided goods only.

I mean, Spanish income taxes mean higher wages need to be paid to Spanish workers; it has no negative effect for Chinese competitivity. The same happens to any other taxes, but for VAT. VAT is applied to Chinese, German, etc. imports as well as to local production, hence it makes Spain more competitive vs. foreign countries. Since exports are not taxed, it encourages exporting.

In other words: if you hike VAT from 16% to 20% in 3 years and reduce other taxes accordingly, the effect is the same as a 4% “peseta” devaluation. Spanish exports get 4% cheaper abroad, foreign exports get 4% more expensive than Spanish products in Spain.

So, according to the author, we could reduce 4% our current-account deficit in a single year without this “fiscal devaluation”, and, somehow, we wouldn’t be able to completely close the gap (another 4%) and get superavit in 3 years with a fiscal devaluation?

Why would we improve it only by 2%? It’s a made-up number.

Diego Méndez,

You say “my point is the analysis is flawed.”

Well to reiterate something I said the other day, does that even matter?

Once you accept the market as the potentia absoluta, the underlying truth ceases to become relevant. The only thing that matters is what the market says. The essence of your assertion is that the market is operating contrary to the underlying truth. If that is so then the market is no longer the invisible hand but the hidden puppeteer. The market says the Club Med nations are to be the sacrificial lamb. All bow down to the omnipotent and all-knowing market!

And your VAT analysis seems flawed. If the VAT is a consumption tax on both imported and domestic goods, then it seems like this would have the effect of diminishing the consumption and production of domestically produced goods by making them more expensive. Wouldn’t this be deflationary? If you raise wages to compensate as you say doesn’t this make Spanish labor less competitive in the international marketplace?

DownSouth, 1) on VAT: you are wrong, I am right. Total taxation is not increased; taxation is decreased for Spanish exports and increased for imports to Spain. It’s the same as a tariff. It’s the same as a devaluation. And it’s perfectly legal.

2) on the market: the market can say my company won’t increase sales this year and will fail; it can even refuse financing; but if we at my company work hard (and we do), we have great products (and we do) and we’ve been prudent and don’t need the financing (and we don’t), our company will increase sales this year (and it will). As simple as that.

Every Spanish entrepreneur knows this above all, and that’s why I have great faith in this country. (Look how we’re trying to cheer ourselves up and compare to Mexico: “We will get over this together”, http://estosololoarreglamosentretodos.org/).

Diego Méndez,

1) What you advocate is a decrease in income taxes, which can be designed progressively so that they fall disproportionately on the rich, and an increase in a consumption tax which will be borne disproportionately by the lower classes. Then with a flurry of hocus pocus, you try to make it sound like this tax upon the poor will be painless. Of course it will be painless—-for the rich!

And you still haven’t explained how the VAT tax makes Spanish-produced goods cheaper in relationship to foreign-produced goods. If it doesn’t do this, then how does it motivate the substitution of domestically-produced goods for foreign-produced goods?

2) In the absence of any bailout package, it is the market that will determine a) whether any new credit will be made available to Club Med nations and b) at what interest rates. Does Spain not have need of any additional borrowing? Does Spain not have any debt that needs to be rolled over? Maybe not. But I’m quite sure that Greece has additional borrowing needs (In the immediate future, to the tune of $30 or $40 billion, no?) and that this credit may or may not be made available. If it’s not made available, Greece faces default. If it is made available, it will be at significantly higher interest rates, further squeezing a fiscal budget and current account that are already squeezed.

To argue that markets cannot inflict pain upon an indebted nation, if that nation is passive enough to accept it, is nonsensical.

There’s another assumption inherent in your prediction, and that is that if the tax burden is shifted from the ownership class to the working class, that the ownership class will pass on these savings in the form of lower prices for its goods to the international market. If indeed this were true, this would make domestically-produced goods more competitive in the international market, increase exports and spur domestic investment and production.

In Mexico they have a name for this. It’s called trickle-down economics. And as Carlos Fuentes has written, it doesn’t work. It has never worked.

“And your VAT analysis seems flawed. If the VAT is a consumption tax on both imported and domestic goods, then it seems like this would have the effect of diminishing the consumption and production of domestically produced goods by making them more expensive. Wouldn’t this be deflationary?”

You are correct, the costs of the tax are either passed to consumers, foreign or domestic. Wikipedia has a nice example of the VAT’s operation on its VAT article.

Note that the manufacturer has to pay the VAT on the raw materials it buys; it is repaid by passing on the extra cost to the foreign retailer to which it sells its goods. This defeats the purpose of encouraging export competitiveness, as the foreign retailer is likely to seek a cheaper alternative.

If the government tries to help out the manufacturer by reducing the manufacturer’s other taxes (which allows it to reduce the prices of its goods and still maintain the same profit), then the cost is passed on to the government in the form of less tax revenue, which is ameliorated by either more government debt or higher taxes on Spanish households.

DownSouth and anonynomous 12:52,

I advocate an increase in VAT and a decrease in taxes paid by local producers, possibly including corporate tax, income tax and social-security charges. DownSouth, I didn’t propose to lower income taxes for the rich; you are accusing me of something I didn’t say… please examine your behaviour. In fact, I think (as I’ve repeatedly said in NK) income taxes should be increased for the rich.

But on average (and with all wealth-redistributing mechanisms you may want), VAT must be increased and other taxes must be decreased.

Once VAT is increased, German imports get more expensive in Spain. Once social-security charges, etc. are decreased, Spanish products get cheaper in foreign markets. On average, the combined effect of a VAT increase and other tax cuts mean Spanish products get no more expensive in local markets.

I think this is very easily understandable. I can’t see what’s your problem. Moreover, it’s been done over and over again in Europe; it’s nothing new.

Anonymous said: “the costs of the tax are either passed to consumers, foreign or domestic”. Yes, that’s true if you don’t decrease any other taxes; if you decrease taxes on local production, the costs of the tax are mainly passed to Germany and China! (Some of it does indeed fall on local consumers, as in the case of a tariff or a devaluation, which I explicitly compared my proposal to).

“Note that the manufacturer has to pay the VAT on the raw materials it buys; it is repaid by passing on the extra cost to the foreign retailer to which it sells its goods.” Not at all. Raw materials’ VAT is canceled against VAT in sales to local retailers, even if they only make a fraction of total sales.

So for exporters, a VAT increase does not mean higher taxes nor higher export prices; but a decrease in any other taxes, means a decrease in the final export price and, hence, an improved competitiveness.

“I think this is very easily understandable.”

Was that a joke?

Yes, I get the discussion because I spent too much of my life around tax policy, but does it not occur to you (in all the many arguments you constantly get into with the knowledgeable contributors to this site) that maybe this topic is complex? What percentage of the general population do you think would understand your argument? How are you going to convince them if you’re having a difficult time with DownSouth (who is obviously an outlier in thoughtfulness)? Do you not realize that we don’t necessarily have a “better” equilibrium to select, but that we have tradeoffs that are going to affect different people differently? You don’t think there will be unintended consequences of your VAT proposal? You don’t think it will be worse for some and better for others? Who are you to choose and start pontificating on what choices are best for everyone else? Even if you’re “right” about overall utility of the society, again, how do you expect to convince the masses, who have neither the intelligence nor the education to follow your arguments?

I don’t want to be an asshole, but even though you’re clearly intelligent and you clearly know your way around much of this analysis, I’m going to bet that your constant overconfidence in your own ideas is eventually going to undermine you. I could be wrong.

Diego Méndez,

You say “I can’t see what’s your problem.”

The problem is that the only thing your nifty little tax “solution” would achieve is to shift the brunt of the tax burden from the rich to the poor. That’s the net effect of increasing consumption taxes and decreasing income taxes.

Here’s a report that explores the phenomenon in great detail. Looking across all states in the US (each state has a different tax regime), we find that the lowest earning quintile antes up 7% of their income for sales and excise taxes, and almost nothing for income taxes. The top 1% of earners, on the other hand, forks over less than 1% of its income for sales and excise taxes, but over 4% for income taxes.

–Institute on Taxation & Economic Policy, “Who Pays? Distributional Analysis of the Tax Systems of All 50 States”

http://www.itepnet.org/whopays3.pdf

Consumption taxes, such as the VAT as you propose it, take a much greater toll on the poor than they do the rich.

If your desire is to murder the poor, while at the same time letting the rich pay very little, your proposal fits the bill perfectly.

Diego,

This also from the linked study:

The Kind of Tax Matters

State and local governments seeking to fund public services have historically relied on three broad types of taxes — personal income, property, and consumption (sales and excise) taxes. As can be seen by our analysis of the most and least regressive tax states, the fairness of state tax systems depends primarily on which of these three taxes a state relies on most heavily. Each of these taxes has a distinct distributional impact, as the table on this

page illustrates:

• State income taxes are typically progressive — that is, as incomes go up, effective tax rates go up. On average, poor families pay only a tenth of the effective income tax rate that the richest families pay, and middle-income families pay about half of the effective rate on the well-to-do. Of the three major taxes used by states, the personal income tax is the only one for which the effective tax rates typically rise with income levels.

• Property taxes, including both taxes on individuals and business taxes, are usually somewhat regressive. On average, poor homeowners and renters pay more of their incomes in property taxes than do any other income group — and the wealthiest taxpayers pay the least.

• Sales and excise taxes are very regressive. Poor families pay almost eight times more of their incomes in these taxes than the best-off families, and middle-income families pay more than four times the rate of the wealthy.

Sales taxes such as the VAT are regressive. But that’s more than compensated by the fact that income tax cuts may be applied only to the poor, hence making my proposal progressive (let me repeat my proposal: increase VAT “with all wealth-redistributing mechanisms you may want”).

Unless you think that a poor paying 1.000$ more in VAT and 2.000$ less in income tax is being murdered (while taxation for the rich is increased, and total taxation staying the same), I can’t see any murder.

Diego, foreign consumers are under no obligation to buy more expensive Spanish imports. You are being obtuse in ignoring this.

““Note that the manufacturer has to pay the VAT on the raw materials it buys; it is repaid by passing on the extra cost to the foreign retailer to which it sells its goods.” Not at all. Raw materials’ VAT is canceled against VAT in sales to local retailers, even if they only make a fraction of total sales.”

And the local retailers must pass on this cost to the Spanish consumer or face lower profits (which they will probably face anyway as Spanish consumers will respond negatively to higher prices on the goods they purchase).

“Once VAT is increased, German imports get more expensive in Spain. Once social-security charges, etc. are decreased, Spanish products get cheaper in foreign markets. On average, the combined effect of a VAT increase and other tax cuts mean Spanish products get no more expensive in local markets.”

You forget that to accomplish this, you are reducing net revenue for social-security programs, which hurts Spanish households. One hand gives what the other hand takes.

“Diego, foreign consumers are under no obligation to buy more expensive Spanish imports. You are being obtuse in ignoring this.”

The idea is to make exports cheaper to increase market share.

“And the local retailers must pass on this cost to the Spanish consumer or face lower profits.” Yes, but that is compensated through tax cuts in other areas (e.g. retailers may pay lower social-security charges to workers; consumers may get higher take-home salaries through cuts in income tax: consumption would be marginally lower, and job creation would be marginally higher).

“You forget that to accomplish this, you are reducing net revenue for social-security programs, which hurts Spanish households.” Why? Taxation is not decreased. You just have to fund social security via taxation (e.g. through VAT, funds allocated by the government, etc.).

And to take the Jesus Christ metaphor a little further, consider this comment by Parenteau:

It is not out of the question that fiscal rectitude at this juncture could place the private sectors of a number of nations on a debt deflation path – the very outcome policy makers were frantically attempting to prevent but a year ago.

Christ is the rank and file of a “number of nations” who will be sacrificed on the cross so that humanity (elites in all nations plus the rank and file in nations outside of “a number of nations”) can be absolved of their sins.

Diego:

Let me be clear: I sincerely wish Spain and all the citizens facing these challenging tradeoffs the best. All I wish to do here is provide a coherent, consistent framework for making some tough choices.

Perhaps Spain can continue to reduce its current account deficit at a rapid pace without deflating domestic private incomes. Perhaps through innovation, higher labor productivity, a better tax mix, Spain can steal market share from other eurozone nations – even Germany.

You seem to recognize that just displaces the problem to other nations in the currency union – which is why it is called a “beggar they neighbor” approach, and so at best is a solution for the first mover, until the second mover shows up.

Perhaps all the peripheral eurozone nations facing tough trade offs can follow Spain’s example, and through inspired entrepreneurship and risk taking and sheer hard work and perseverance, they can grow the global markets for their tradable goods.

My only point is unless a trade revival occurs, attempts at achieving fiscal sustainability are likely to put the private sectors of these economies on a precarious path which may involve a debt deflation dynamic taking root.

That possible outcome, which usually involves a lot of human suffering, wasted productive resources, and financial disruption, does not appear to be clear to many people. Indeed, those advocating for an “internal devaluation” approach are for the most part, unwittingly or not, opting to risk a debt deflation outcome for their private sectors.

The financial balance approach makes these trade offs clear. You cannot execute a fiscal retrenchment from here without risking putting the domestic private sectors back (or deeper, in some cases like Portugal) on a deficit spending path, or worse yet, a falling nominal income path that will beget more private debt distress, unless you can pull off an offsetting swing in the trade balance at the same time. That much we should all be able to agree upon – or else we need to toss aside 500+ years of double entry booking.

It really is that simple…and yet, somehow it eludes many policy makers, investors, economists, commentators, citizens, etc. The time has come for us to wake up, face reality, make informed choices, and take bold, creative action. Those who can see the financial balance framework may find they have an edge.

best,

Rob

Sorry if I was too blunt, but I sincerely think your analysis is flawed.

You know perfectly well your numbers and conclusions would have been much different if you have used other assumptions, e.g. Southern Europe improving 6% their current-account deficit over the next 3 years, while maintaining large (but admissible given the circumstances) fiscal deficits in the 4-5% range.

This is a much more realistic scenario, and you’d have to conclude that Southern Europe would be exporting their problems away to Germany and China. This may be called a beggar-thy-neighbour policy, indeed; but it can also be defended as a balanced-growth strategy.

Southern Europe can’t grow balancedly any more via increased, debt-fueled consumption and investment. Germany and China can’t grow balancedly any more via net exports. So by exporting our problem, we’re forcing Germany and China to adopt policies that increase consumption.

For Germany, that may mean more tolerant immigration policies, service-sector liberalization (hairdressers should not need 3 years in education) and economic/fiscal policies leading to higher debt and housing ownership.

For China, social services (healthcare) and a higher exchange rate.

I agree, ideally, there is a global rebalancing that must go on. The countries running trade surpluses now must become sources of global demand for the products of those nations trying to swing their trade deficits around, otherwise it is just beggar thy neighbor (stealing market share from each other in a recurring fashion, often with a race to the bottom) especially in a currency union like EMU, where most of the trade is intra-eurozone (and this is a point you do want to take in). You may have read Martin Wolf’s Feb. 23rd FT article on this issue – if not, it is worth the read, and it is another illustration of using the finanicial balance approach.

However, my experience is outside attempts at forcing German or Chinese policy makers to do anything they did not think of first are, well, somewhat futile…if not likely to boomerang on you. Remember, they are running export led growth strategies. The structure of their productive capital stock is locked into that path. They will not be likely to take loss of market share in tradable products lightly, which is the precise forcing mechanism you allude to, I believe. And as evident from the map, countries running current account surpluses have much better odds of avoiding persistent private domestic sector debt build ups, which is a quality they may not wish to give up without a fight.

So yes, you can use the financial balance framework and disagree with my assumptions. I offer one possible scenario that strikes me, for reasons I have reiterated several times now, as plausible. Perhaps I am not optimistic enough about the prospect for chronic trade deficit nations in a fixed currency zone to avoid simply poaching market share from each other as they try to swing their trade balances around faster than they cut their fiscal deficits.

Or perhaps I am too optimistic, and the only way Germany, China, and other chronic current account surplus nations will be “forced” to change their economic growth strategies is by finding the foreign debt they hold has defaulted, the foreign bank loans they provided are producing unexpected losses, and their export growth is declining again, as internal or fiscal devaluation efforts simply yield domestic private income deflations in the chronic trade deficit nations.

So please drop me an e-mail in 6 months and let’s compare notes. My fingers are crossed that we can be smart enough to avoid any more Latvia like implosions, which is part of the reason I wanted to put the financial balance framework in front of more people now. We have to understand the nature of the choices available and their possible outcomes, or we are likely to keep doing stupid things to ourselves.

best,

Rob

“Pray there is life on Mars that consumes olives, red wine, and Guinness beer.”

That one line brought it all into focus for me. Well done!

He could have said as well: “Pray there is life on Mars that consumes information technology (Ireland), ships (Greece) and cars and green-energy equipment (Portugal and Spain).”

But somehow an accurate description doesn’t fit into the narrative.

Does Spain build solar equipment competitively? I realize that there were many solar factories in Spain a few years ago, but I thought that was due to government subsidies. Without the subsidies, is it more competitive than China?

Spain’s edge is not on PV solar, but on thermal solar and especially wind-energy equipment. Of course subsidies are a huge part of the story, as are in Japan, Germany or Denmark (or as were chips in California in the 80s).

But we’re very competitive at windmills. We’ve got Gamesa, one of the world’s leading windmill manufacturers; Iberdrola Renovables, the world’s largest green-energy utility (building lots of energy parks in the US now); or Abengoa, which has been experimenting with “rare” energy sources, such as bioenergy, large solar thermal centers, etc.

This was illuminating.

Would you apply this sort of analysis to Japan for us and what it means for the US going forward? Was their trade surplus too small compared to their private sector deleveraging, forcing the govt to run large deficits for a very long time? But overall debt didn’t go away–so eventually the govt sector will need to deleverage. What do you see as the endgame for Japan?

SP –

Yes, you get it. I may follow up with a later piece on the US, UK, and Japan. For now, you can find my earlier assessments of the US scattered on various websites or in issues of the Richebacher Letter.

In Japan, as elsewhere, the bursting of the asset bubble in 1989-90 led the private sector to seek a high net saving (financial surplus) position. This is the typical response of household and businesses, for what should be obvious reasons. Investment in tangible capital is put on hold once an asset/credit bubble bursts, and saving out of income flows is increased.

If nothing else changes, you get a collapse in private income. If there are high private debt to income ratios, which often are a residual of asset bubbles, widespread bankruptcy, and a debt deflation dynamic can result, leading to political and social disruption, to put it nicely.

If you are really lucky, your exports become so cheap along the way, and your import demand collapses enough, that the current account (trade) balance improves dramatically, and a collapse in nominal private income is short lived and quickly reversed by an increasing trade surplus.

But even Japan, which at the time was considered way out on the technological frontier with best practices and whiz-bang technology, could not pull that one off. Much of the rest of the developed world went into recessions or very slow recoveries from 1990-3, so the demand for tradable goods simply was not strong enough.

As a consequence, nominal income for Japan has been roughly flat for two decades as fiscal deficits have filled in that part of the gap that the current account surplus did not. I would urge interested parties to read Richard Koo’s recent books if you would like a more detailed understanding of this process.

Koo does not lay out the financial balance approach as explicitly as I have for you, but he clearly thinks in these terms (as do Martin Wolf, Andrew Smithers, and a small handful of others who have been willing to apply Wynne Godley’s pioneering and yeoman efforts in this direction).

My only quarrel with Koo’s version – and this is a common mistake, as you can see in one of my responses to Diego yesterday – is he often writes as if the private sector net saving is mobilized and put to work by the fiscal deficit. In fact, if you understand the financial balance approach, you must realize the private sector cannot net save during any accounting period you chose to analyze unless the remaining two sectors – foreigners and government – are willing and able to net deficit spend. Or to put it more generally, as I spell out in the article, the current account balance must exceed the fiscal balance in order for the domestic private sector to run a financial surplus.

Hope that helps. Once you get the financial balance framework, it can become a very powerful lens. I have been working with it for close to 15 years now, and I can tell you it has proven extremely illuminating, in no small part because it forces you to think coherently and consistently about macrofinancial issues – something that is all too rare, even amongst the most sophisticated policy makers and institutional investors I encounter in my work. And it really is quite straightforward – just double entry bookkeeping applied to macro. You’d think it would be self evident, but there has been so much thinly veiled ideological claptrap pedalled as macroeconomic and financial market theory in recent decades that we are all too smart to see it.

best,

Rob

“there has been so much thinly veiled ideological claptrap pedalled as macroeconomic and financial market theory”. Very well put. And thanks for your reply–I’m finally learning something.

But I’m still trying to wrap my head around the ideas that follow from the financial balance framework. Meaning I fully accept the principles, but I’m not comfortable yet with the conclusions.

In your description you seem to treat debt and deficits as the same (i.e. deficits = change in debt). If so, that would imply that accumulating all the debt in this bubble was only possible by either fiscal surplus (not) or trade deficits in the US. That doesn’t seem to add up–debt is created out of thin air after all, and low lending standards allow debt to be created much faster than trade deficits can. So if we can accumulate debt much faster, then by symmetry we should be able to eliminate it just as fast (and independent of the trade deficit). Default is one way, the equivalent “thin air” counterpart of just creating debt. So we don’t necessarily have to have the private sector run a surplus to pay down debt–they can just default that amount every year. It would seem to me that a proper prescription for a bubble aftermath would be to ensure some minimum amount of default to help deleverage (and avoid some of this financial balance conundrum). If this can’t be done, then this asymmetry should serve as a strong reason to not allow debt to accumulate to such a degree.

The other main thing is what I alluded to earlier–what is the endgame? Sure, fiscal spending can buffer a fall in demand as the private sector deleverages post-bubble. But when do you (can you) stop? If you freely use fiscal spending to fully counter private adjustments, don’t you mostly transfer debt from one sector to another? So you avoided a depression for a few years, but then what? Default/inflation/devalue? Again, what do you see happening in Japan going forward? This all is what I’m most truly concerned about. It is not at all clear to me that this path is the best one in the long term even if looks best in the short term.

I’d appreciate your thoughts. Or give me links to posts you’ve made that cover these topics.

SP:

If a sector is running a financial deficit (saving less than investment, expenditure greater than income) it can issue liabilities to other sectors, run down existing cash balances, or sell assets to other sectors, (or default).

2 & 3 are limited by existing holdings (and their valuation in 3).

1 is less limited.

Liabilities issued can be debt, equity, or hybrid forms (although household sector does not generally issue equity).

Since 1 is the typical choice, sectors running financial deficits tend to build up debt on their balance sheet.

Have to run, but hope that straightens out some of it out for you.

Rob, when you have a moment, I’d love to see a more fully developed response to SP’s points about the creation and destruction of credit (and its relationship to your financial balances approach) as well as potential endgames (ideally perhaps taking Japan as your example).

Ingolf and SP:

Perhaps I will do a follow up piece on how credit and money creation feeds in to the financial balance approach. Suffice to say if banks can create money by issuing loans or buying assets, and credit standards decay under competitive pressures or a run of good times with low losses on loans, lots of individual households and businesses can end up spending in excess of their income flows.

So, for example, I find the true twin of the current account balance is not the fiscal deficit, but the household sector financial balance, which is a subset of the DPSFB. And that makes sense, as home equity loans were used to buy flat screen tv’s from abroad, to put it too simplistically, but not that far from the mark.

Regarding the endgame, there will be no one endgame. There will be a whole spectrum of endgames depending upon private debt to GDP ratios, currency systems, whether external debt is denominated in another currency, social unrest, and much more.

In some cases, the result will be akin to Japan’s, where Koo argues fiscal stimulus was never sustained enough and large enough to get the economy to escape velocity from deflation. You can get higher budget deficits actively by pursuing stimulus plans or passively as automatic stabilizers kick in with slow growth or recession. Japan, Koo documents, mostly did it the latter way, which was not smart, but that is all policymakers dared to do. I think there is also an argument to be made that bridges to nowhere did not help, and public investment aimed at speeding the transition to new industries/technologies could have offered more favorable results.

Some will unfortunately be like Estonia and Latvia who are going through their version of the Great Depression as I type (http://www.scribd.com/doc/26281591/Latvia%E2%80%99s-Recession-The-Cost-of-Adjustment-With-An-%E2%80%9CInternal-Devaluation%E2%80%9D)

Others may get away with an Argentina 2001-3 (http://www.scribd.com/doc/417958/Argentinas-Economic-Recovery-Policy-Choices-and-Implications).

Beyond that, you’ll have to troll the net for other pieces I have written along the way, or check out the Richebacher Letter.

I have more to say, but for now, your discussion implies Japan’s stagnation is their endgame–I see it as a long midgame. What do you see for them going forward from now? Would yet more fiscal spending have really helped them achieve “escape velocity” or just add more to anchor them down from future growth?

I see the help in understanding that the financial balance approach provides. When one goes from there to prescribing policy, my intuitive alarms go off: 1. Could just pumping fiscal spending only serve to address the symptoms of the underlying problems and not the causes (e.g. excess inequality, debt, etc, that isn’t accounted for in this framework)? 2. In the limit wouldn’t just looking at the GDP balance equation (in a vacuum) tell us to do away with the private sector so the gov’t has full ability to maximize employment at all times? Seriously.

Fundamentally, I think additional unspoken assumptions are being introduced when you jump from the “understanding” part to “policy prescription”, and those need to be exposed and evaluated. I do fully see the value of pointing out that mindlessly balancing budgets may cause that downward tax spiral that isn’t obvious. But for Koo to imply Japan needed even more stimulus? I fear Japan’s (and the US’s) true endgame.

SP –

Read Richard Koo on Japan. As you read his analysis, think about the nature of the anchor on future growth you describe. What precisely is the nature of the anchor?

Higher interest rates? Not for the last two decades. Higher interest expense? That transfers income from one set of Japanese households (taxpayers) to another (households)…so the net loss is? Turns out the real per capita GDP growth for Japan has been equal to that of the US over the last decade. So think hard about the nature of the anchor you see.

On policy implications, I want to be clear the financial balance approach is not the only consideration. Of course there are other aspects to the problem at hand than flows of cash and finance. There are issues of technological innovation, demographics, entrepreneurial culture, etc. which cannot be ignored. And as a general rule, I would suggest anyone telling you they have the one true analytical technique and solution to current macrofinancial dilemmas is either selling you snake oil or waltzing off into a pit of unintended consequences. Our models of the complexities found in the world of macrofinancial dynamics are all simplifications and so by definition flawed representations of the world we actually inhabit. A dose of humility, which is rarely found amongst economists and central bankers and investors these days, is wise in all these matters.

As for the government ending up taking over the economy, I do not see how that follows from anything I have presented above. What the financial balance approach does show however – and Greenspan corroborated in 2000 testimony – the surest route to the government taking over the economy is for the government to run a fiscal surplus for ever. They then pay down public debt and begin accumulating private assets. Think about that.

I think this is all leading up to, perhaps unknown to those pursing these options, a global currency which I expect to be in place by 2015.

Jerry –

More likely, if I am right that fiscal retrenchment, or the attempt at it, will not be met with a sufficient and offsetting increase in peripheral eurozone nation current account balances, the results may prove sufficiently distressing that the idea of a currency union, or any likeness thereof, may be a hard sell for some time (at least one without a sufficient political union or some other feasible adjustment mechanism).

Of course, I could be wrong. There are enough “smart money” hedge fund types accumulating gold these days to suggest someone is questioning the longevity of current fiat/credit monetary arrangements beyond the usual merry band of gold bugs and LibertAustrian true believers.

best,

Rob

@Diego Mendez 1:32 pm………………

“Once VAT is increased, German imports get more expensive in Spain.”

Yes, but on the other hand doesn’t this mean that Germany sells less product in Spain and therefore has less money to buy Spain’s exports? Spain’s VAT products may indeed get cheaper in foreign markets but the buyer of those products must also be willing and able to increase those purchases to benefit Spain all other things considered.

And one other thing, whenever I hear VAT I equate it to non-essentials. To my mind in what appears to be a deflationary global environment (actually stagflationary to be more precise) an increase in VAT these days is the same as increasing the price of luxuries. I find that to be analagous to at best treading water under the dubious expectation that this will somehow get one to the other side of the pool.

Bottomline: I see no ‘growth’ prospect with your approach but perhaps hopefully maintaining one’s head barely above water in the long run.

F

To all:

Some feedback below from a colleague on Cavallo’s fiscal devaluation proposal which sheds more light on the effectiveness of this approach in the case of Argentina:

“Cavallo was making no headway at all…every time he cut government expenditures tax yields fell by more and the deficit increased, as you would expect– that’s why the economy eventually collapsed: growth kept falling and the deficit kept rising.

Added to that was the refinancing of maturing debt at much higher interest rates with grace periods to reduce current funding costs (same technique as in Greece) which markets eventually figured out could never be repaid at the new repayment schedule. It had nothing to do with the failure of IMF funding.”

So this points out what we might call the paradox of public thrift. Cut the fiscal deficit, and domestic private income flows slow (or even fall), tax revenues come up short, and the original fiscal target is mixed, unless of course the current account balance increases soon enough and fast enough, which is not guaranteed.

Then compound the dilemma by tightening fiscal policy even further to get back on track for the original target (surely a condition that will be built into any assistance packages that develop for Greece and elsewhere)…and, well, Argentina knows the drill from a decade ago. Probably a few Eastern European nations that could recite the drill as well from more recent experience.

How many times do we really want to replay this movie?

Rob,

My compliments on a pair of very illuminating articles.

CB

So, as per your 9:03 p.m. comment on your post yesterday, Cavallo is urging the same treatment for Greece now that he tried in Argentina, and that failed so miserably.

What is that saying about doing the same thing over and over and expecting to get a different result?

DownSouth, Cavallo must know about this more than anyone else.

Quoting Niels Bohr: “An expert is a person who has made all the mistakes that can be made in a very narrow field.” :-)

The solution is for Germany to leave the Eurozone.

Isn’t Cavallo generally estimed a rat-ass bastard? The finance minister who implemented the neo-liberal currency board/peso-dollar peg policy, which eventually resulted in Argentina’s economic collapse and default and the popular revolt that virtually overthrew the government and him with it?

Yes, the very same…bitter, much?

Always! It’s the authentic taste of life.

Know it well…although I also find there is something to this “take the lemons you find and make lemonade” platitude.

“I like pigs. Dogs look up to us. Cats look down on us. Pigs treat us as equals.” Sir Winston Churchill

I like PIGS too and I am rather optimistic about their future.

In my view, the UK is looking much like Greece these days, except without the constriction of the Euro.

http://whatisthatwhistlingsound.blogspot.com/2010/03/ticking-sound-in-uk.html

Yes, the specs are getting bored with Greece, especially with rumors of fiscal assistance packages being formed. So the erstwhile locusts move on to the next ripe field…US, Japan, to follow before they make their 2010 bonuses. God’s work to do, don’t you know…

Concerning Portugal, the author is wright.

Portugal rose the VAT (IVA) from 17% in 2002 to 19%. Later in 2005, from 19% til 21%. In 2009 the level of that tax changed again, but to 20% after the error of two governments. Governments who believed in the “new” theory: rise VAT, to stop imports and help the local producers.

What are the results? Nothing changed except more pain to poors.

Please, check source: Banco de Portugal.

http://www.bportugal.pt/pt-PT/Estatisticas/PublicacoesEstatisticas/BolEstatistico/Publicacoes/C.pdf

The level of external debt didnt changed at all. Only in crisis, when the private consume falls the debt falls also.

Today we must to realize a simple truth: high level of interests inst bad for some countries.

For Portugal, isnt the level of interest rates that counts. Is the level of productivity and internal savings.

So, portuguese must save more, consume less, work better (addding value to their production) and export more (or import less).

The main problem to Portugal (Portugal isnt the only that must attend that fact) isnt China or Turkey. Is Germany. Because Germany is doing a good job to control unit labour costs to improve their competitiveness. Portugal didnt did the same and is trying to do that.

In 2009 the salaries fell 2,5% for young workers. In 2009 we had deflation of 0,8%. Thats the way the market is trying to control his costs to export more and better.

So the benchmark to Europe isnt China or other devevlopment cowntry. Is Germany. Is Germany that we must follow. So we, portugueses, must follow Germany.

The author is wright. Someone has to pay to balance the equation. Or someone has to be better at producing goods and services. We are doing the mix trying to not aggravate the current global crisis internally.

Best regards.

“Is Germany that we must follow. So we, portugueses, must follow Germany.”

You mean the same Germany that increased VAT and reduced social-security charges in January 2007, which spurred hiring, lowered unemployment rapidly and increased competitiveness?

I personally don’t know about tax reform in Portugal. From abroad, it seems obvious Portugal’s problems had a name: China. It’s Chinese clothes and other low-tech product which sweeped large parts of Portuguese industry away. But that effect will probably subdue soon.

Dear Diego,

Its Germany who is leading the way. Is german industrial policy that is changing their economic scope. Today 1 in 5 german worker depends of their exports. Today, even with €uro strong, Germanys still exports to everyhere.

The new theory, rise VAT to fight imports, doesnt work. Portugal learned that lesson. You can check the payments balance and see what is the true lesson.

What is my main attention isnt jobs losses to China. That jobs dont pay more that 300 or 400 euros by month. I couldnt live with that salary per month. Do you? But I have friends and family members that earn something like that by month.

What we want is selling a pair of shoes by 100 euros and not one, with lower value added, by 20 euros. We want to sell a machine with high value addedd and not small pieces to some automative competitors, with low margins and low wages. We want to sell good wines by 100 euros a bottle and not some “cabernet sauvignon” by 2 euros a bottle.

What I mean is. We portuguese must do things that is valuable by the costumers and they pay well for that. That is our aim and, for first time in years, portuguese shoe makers sells their producion at high prices than italians. Because we have good production with high quality, good design and high environmental proteccion standards. This is an example how old portuguese low value added producion is changing. And our competitors arent cheap and low quality production like chinese or others. Our competiores are italians, for example. Our competitors must be the leaders in the markest that were compteting. The portuguese shoe sector are growing in average prices to the market and is a lesson to all of us. Compete with the best and not with worst. And now this old sector is adding better jobs with high wages to his emplyees.

Another example. A long time ago it was scandinavian pulp and paper producers that made the benchmark for the rest of the world. Today, the portuguese has the best producer of the world and were the benchmark. The best paper for offices or specialized printers are made in Portugal and that industry is adding jobs. That jobs are better qualified with high wages. And were using our natural resources, the forests. The producers of the paper and pulp are managing betters our forests, accomplishing the high standards concerning environmental proteccion and even producing energy with forest residues.

So arent chinese that is treating our living standards. Are the others competitors who are doing a good job producing goods and services with high value addedd. Like Germany, Japan or even France.

Who is living in south Europe and is thinking in chinese competitors have a destiny: loosing their standards of living. Thats is the lesson here. And to fight against the best we must focus in industrial policys like germans do. They do in regional perspective and even in large industrial clusters across all Germany.

So in macroeconomy perspective we should to help the producion. Producion of goods and services. And not to parasite that producion to help some parasites, like some reent seeking sectors. That is the lesson to Portugal that were learning. We do a lot of mistakes and we do them early than others. Portuguese tend to be an earliers adopters of new ideas and trends. Politically, social and economi trends. So we make mistakes before others. I dont to want to talk about othes mistakes but we are seeing the same mistakes that we did in the last 30 years.

You are absolutely right and I agree completely with you. Southern Europe must make a historical bet on high-value-added products, R&D, innovation, a better educated workforce and world-class infrastruture. There is no point in competing with China on salaries.

However, sectorial (micro) analysis has a point. If you want to know why Spain did better than Italy or Portugal over the last decade, it’s for a micro reason, not a macro one: Italy and Portugal made excellent clothes, home clothing and furniture for medium-range prices. But demand for medium-quality, medium-priced products disappeared as soon as Chinese dumping practices (yuan peg) made low-quality, low-priced products the obvious choice for the buyer.

Spain just happened to be lucky since those industries were not so important to the Spanish economy.

Let’s put my case differently. Portugal’s structural change needed money; without China, that money would have been there. Since it wasn’t, Portugal lost a decade. It’s not that medium-priced home clothing had any future anyway; but that home clothing could have financed nanotechnology research centers all over Portugal 10 years earlier.

On Germany and VAT. Of course you can’t compete via tariffs, currency devaluations or fiscal devaluations (as proposed by me) in the long run. However, in times where financing is scarce, a fiscal devaluation means a one-off financing shot in order to finance an economic-model transformation in the medium term, i.e. in order to finance an easier transition to the future, innovative economy both of us want for Southern Europe.

Diego –

You are still not acknowledging an underlying point: there is no fixed pool of savings from which finance can be drawn. Your last paragraph demonstrates you have not escaped this fallacy. I should also add, in a world where bank loans (and asset purchases) create deposits, finance is never dependent upon prior savings flows.

If there is anything holding financing of new private investment back now (and bank credit growth has screeched to a halt in the eurozone), it is banks perceiving a lack of credit worthy private borrowers (as well as, in the eurozone, concern that the banks themselves are too leveraged).

Pursuing a rapid path of fiscal retrenchment against the current economic situation, which is at best a tentative and heavily policy fueled recovery from one of the deepest recessions and largest financial meltdowns the world has seen since the 1930s, will tend to produce even fewer creditworthy borrowers in the domestic private sector.

That means the CFO’s of the new industries and technologies, which I entirely agree are part of the solution, are likely to find it is even harder to get funding for their projects under such conditions.

Do consider that possibility.

Dear Diego,

First of all I want to sorry on my bad english. Im not good in foreign languages as before. I could wright in sapnish but with the same mistakes as in english. Im so sorry about that.

We agree in the basic principles. But not in the short term. if we all will do the same, trade wars, we will get another great depression, as in the thirties. My view, as others in Portugal (the mainstream) is this: work for the long run not the short term. We did before and we didnt change wnat we wanted and the costs are high.

Is true that we needed to have acess to international markets. But with low interests rates we got a flu, like the ladrillo in real estate. The problem is the anglosaxon point of view: debt, debt and more debt. Do you understand the industrial policy in USA? Or UK? Or at least: have they industrial policy? No. Bump and ride. Or similar: create financial bubbles for financial sector and everyone will be happy. But that isnt my business point fingers tn others. We watch others mistakes and we try to learn with them.

In Portugal we have two kind of problemas. Internal, like lack of compettiveness and the others imported. But were trying changing things and profiting with the opportunities. It take time. A lot of time. The old shoe sector show us that we need, more or less, 20 years to be competitive. So, insted of pushing things we must to work and to be patiente. Not mamboo jamboo economics but old adage: work, work and more work.

Soon or later we will get what we want.

Saludos. ;)

Rob,

money (credit) can be created easily; resources cannot. Financing our future means better universities, more investment in R&D programs, more seed capital, etc.

In the US, where critical mass was reached half a century ago through public (military) programs, it’s easy to point to private financing. But in countries with (alas!) a very short scientific/start-up tradition, we’re talking about public programs.

If the next Google is to be Spanish, it will have to receive public seed capital (I know all this sounds very strange to your American ears).

It’s much easier to increase an additional 10% of state budgets to R&D, education, public venture capital, etc. when you can tax traditional export industries, such as home clothing, than when they have disappeared because of Chinese dumping salaries and you have to pay more unemployment benefits.

That’s what I meant by financing your future. Of course (private) credit can be easily created; but in the very long term, as PJM acknowledges, what matters is public intervention creating critical-mass investment in new areas.

I don’t expect you to agree, since all this sounds so socialistic and foreign to the US, but let me ask you a question. As you know, most productivity growth in the 50s, 60s and 70s was due to mass car ownership. What would the US have become if Eisenhower hadn’t decided to create the largest public investment program in History, namely the US interstate highways?

Diego –

I agree with the concept. I am quite aware of the importance of public investment, not just in standard infrastructure, but also in pushing into new industries and technologies. Asia certainly knows the value of such measures. The US once knew it, but forgot, even though it is a critical part of its history.

both the public sector and the domestic private sector cannot deleverage at the same time unless Spain produces a nearly unimaginable trade surplus

This statement is only true in the aggregate.

What needs to be done is to deleverage failure in the private sector and failure in the publice sector.

Once you deleverage these ttw failings you move on.

So. All you have to do is give vouchers to private citizens that has to be spent with in 3 months, 6 months, 12 months time. Use it or lose it. Staggered, so the private sector has time to actually meet production.

Pay for it by firing government employees and cutting their ill got gains of pension benefits.

As a general rule, it is not such a good idea to divorce income from production.

Wall Street tried that in the US – look where it got us.

Gesell money (google Silvio Gesell) experiments were tried in Japan in the past decade. Their private sector has managed to deleverage, as Richard Koo details. Go look at what they found with their stamped money efforts. I presume since they did not ramp these up, they were not content with the results.

The post has managed to trigger a very interesting debate indeed. Congratulations.

Apart from the disquisition on the true workings of VAT tax (which probably stems from the fact that the US does not use VAT tax and some US economists -wrongly- assume it works as the US sales tax), have you stopped to think about the importance of economic knowledge and competence that PIGS’ policy makers truly enjoy? My experience of Bering based in Spain for 20 years (and the experience I had working a few of those years abroad I interviewing CEOs and economic Cabinet Minsters as a business journalist writing economic country reports for such magazines as US News or Wirschafts Woche) drives me to evaluate the current Political class in Spain as totally incompetent in matters of economy management.

That is the biggest problem on Spain’s road to recovery. Try asking President Zapatero to explain how would a VAT tax I crews effect he current account balance, if you need any further proof.

As for your analisis, I find it intriguing but excessivelly elaborated and presented as a mathematical truth. It isn’t.

To put it plainly: over the past 70 years the world’s governments, corporations and households have accumulated a huge debt and there is not enough revenue generating economic activity to service it’s interest and principal repayment. That is because most of that debt is “bad”: the non-self-liquidating type.

Last year, the banks risked default. With the unusual quantitative easing performed by central banks and the reckless government deficit spending “stimulus package”, that risk of default has been flatly transferred to govrnements. As a government default is catastrophic, the policy makers will eventually to pass the hot Patagonia on to households.

As simple as that.

Note that the resulting effect is persistent deflation and that the US economy runs the same risk as the PIGS economy, although it has more competent policy makers, a flexible exchange Rate and the printing press of the world’s currency.

I have written some thoughtfull analysis on the subject, although it is only in Spanish (google translator may help).

http://leonardmazza.wordpress.com

@leonardmazza

Politicians usually know about one thing only: politics.

Spanish PM Zapatero does not need to know anything about VAT. He just needs to be humble enough to do what his best economists tell him, and sell it politically.

Which is why VAT will be increased from 16% to 18% in Spain from July on.

Today, in Greece, austerity measures were announced in over-dramatic, even by Greek standards, tones. The cuts in the public sector are mild amounting to taking back the raises of the last two years, leaving actual salaries in the public sector quite higher than they were in 2003. Taxes were also raised but the issue remains whether these taxes will be collected. Public sector workers, including the legendarily incompetent internal revenue office, threaten massive strikes. Nevertheless, these measures, if implemented, should be sufficient to reduce the deficit by 4.8 bil euros that is roughly the planned 4% GDP. It is promising that the government is attempting reforms that may improve productivity and also a war on graft. The “war” has started, albeit with a minor advance of the troops of modernization.

correction: by an ADDITIONAL 4.8 billion euros thus roughly meeting the planned 4% GDP.

Yes, modernization indeed advances…and what a coincidence…it then recedes as financial stability erodes in the private sector… because the article below says, of an economic slowdown…how odd…probably doesn’t have much to do with fiscal retrenchment…nah, cuz the trade balance is taking up all the slack, right?

March 3 (Bloomberg) — Five Greek banks, including National Bank of Greece SA and EFG Eurobank Ergasias SA, had their credit ratings put on review for a possible cut by Moody’s Investors Service, which said the country’s economic slump may hurt asset quality and profitability.

Moody’s also put Alpha Bank AE, Piraeus Bank SA and Emporiki Bank of Greece SA under review for a possible reduction, the ratings firm said in a statement today.

“These banks have been facing growing pressures on their financial performance and fundamental creditworthiness as a result of the economic slowdown in Greece,” Moody’s said. “Volatility in the financial markets has also given rise to funding challenges and has led to an increased dependence on short-term market funding.”

Macro, you are making a point. It is important, however, to distinguish between the short term and the long term. In the short term, the recession in Greece will get deeper and everyone, particularly the banks, will feel the effects. Keep in mind that this is really the first recession in 18 years, so a lot of dry wood is available to feed the fire of recession. We will find out how much the Greek households will retrench and for how long. The more important point is that the situation was completely unsustainable and thus, whatever the discomfort, some adjustments had to be made. How unsustainable? You have to go there to appreciate what I mean.

I understand the idea of taking short term pain for long term gain. The problem is, if my analysis is anywhere near right, the transition path may not be sustainable given current private debt loads. I would of course be happy to be proven wrong by events to come.

We shall see. Argentina did rise phoenix like from the ashes of 2001, while Latvia may not be so lucky. I am constantly amazed at the capacity for people to adapt and innovate. although it is true the veneer of civilization can be awfully thin. The hangman’s noose can certainly concentrate the mind, if it does not paralyze it with fear first.

If you have the time, do share some of the unsustainable aspects in Greece that you witnessed. I have heard my share of anecdotes, by I tend not to believe them until they are corroborated by others on the ground.

best to you and I hope you and Diego prove right,

Rob