By Richard Smith

Readers of ECONned will be very familiar with the name of Gary Gorton, author of ‘Slapped in The Face by the Invisible Hand’, which explores the relation of the so-called shadow banking system to the financial crisis. His work is pretty fundamental to understanding some of the mechanisms which made the crisis so acute. Now he’s done an interview, which I would like to have a growl at; but first, he has some basic points about shadow banking, useful later in this rather long post. Gorton explains repo thus:

You take your $200 million to the bank, to Lehman Brothers, say. You deposit it, so to speak, overnight so you can have access to it the next morning if you want to. They pay you 3 percent. And you want it to be safe, so they give you a bond as collateral. But Lehman earns the interest on the bond, say, 6 percent.

..and then “haircuts” (an extra margin of security in case that bond isn’t so safe after all):

There may be a haircut. If you deposit $100 million and they give you bonds worth $100 million, there’s no haircut. If you deposit $90 million and they give you bonds worth $100 million, then there’s a 10 percent haircut.

…and then “rehypothecation”:

If you put a dollar in your checking account and the bank has to keep 10 percent of it on reserve, they lend out 90 cents. Somebody deposits that 90 cents, the bank can lend out 81 cents (because of the 10 percent reserve requirement) and so on. So you end up creating $10 of checking accounts for $1 of demand deposits, assuming there’s a demand for loans…And that can happen in repo as well because if you’re Lehman and I’m the depositor, and you give me a bond as collateral, I can use that bond somewhere else. So there is a similar money multiplier process.

…and finally the link to regulated banking:

And shadow banking very importantly is not a separate system from traditional banking. These are all one banking system.

So much for the preamble. The other point you need to know: we are talking about an unregulated banking system that at its height was just as big as the regulated banking system, yet coupled to it, and apparently more profitable, though, as we now know, much riskier. Now we get to the part of Gorton’s interview that I’m not so happy with:

In summary, I would describe shadow banking as the rise to a significant extent of a very old form of bank money called repo, which largely uses securitized product as collateral and meets the needs of institutional investors, states and municipalities, nonfinancial firms for a short-term, safe banking product.…It’s a valuable innovation.

The bit in bold is where I raised my eyebrows. The truth of the bolded claims depends on the yet-to-be-discovered solutions to repo’s core problem, formulated thus by Gorton:

Of course, the problem with repo and shadow banking is that they have the same vulnerability that other forms of bank money have. We can talk at great length about what that vulnerability is, but loosely speaking, it’s prone to panic. Looking back at history, think about how long it took to devise a solution to the first banking panic, related mostly to demand deposits. That was in 1857. It wasn’t until 1934 that deposit insurance was enacted. That’s 77 years where we’re trying to understand demand deposits and figure out what to do.

The situation that we’re in now, seriously, is one where we are back in about 1860: We’ve just had a big crisis, and we’re trying to figure out what to do. We can only hope that it doesn’t take 77 years to figure it out this time.

That doesn’t sound like a safe banking product to me. Next comes some irritating pussyfooting:

Nobody wants to be given collateral that they have to worry about. And the mechanics of how repo works is exactly consistent with this. Firms that trade repo work in the following way: The repo traders come in in the morning, they have some coffee, they go to their desks, they start making calls, and in a large firm they’ve rolled $40 to $50 billion of repo in an hour and a half. Now, you can only do that if the depositors believe that the collateral has the feature that nobody has any private information about it. We can all just believe that it’s all AAA.

Gorton is polite, and that can mislead. Impolitely: for “private information”, read “knowledge that the collateral is wildly overvalued”, or ”aware that the collateral is backed by assets with massive gearing to fraudulent loans”. The system’s gatekeepers (originators, ratings agencies and credit insurers) had an “agency problem”, (impolitely: issued cows, or rated cows, or insured cows, for money), so the fraud-backed collateral got past them.

Gorton is vague about how this “information insensitive” collateral is to be created. Presumably the options are to have reliable ratings agencies, or some other gatekeeper on the collateral, or a very deep-pocketed credit guarantor (that’s you, dear reader), or all three. But he doesn’t quite spell it out; perhaps that’s just the interview format. What we get instead is this:

We want all securitized product to be sold through this new category of banks: narrow-funding banks. The NFBs can only do one thing: just buy securitized products and issue liabilities. The goal is to bring that part of the banking system under the regulatory umbrella and to have these guys be collateral creators.

Well, I don’t immediately see why a narrow funding bank, thus described, is a more reliable generator of quality collateral than a narrow rating agency, or a narrow monoline insurer, or for that matter, Gorton’s old client, AIG. Why would an NFB be any better than any of those organizations in filtering out low quality collateral, given the demand for collateral? The NFB has exactly the same agency problem.

And are we really sure we know what ‘good collateral’ is? Gorton’s formulation of the problem isn’t quite accurate: it’s the stability of the haircuts that matters, not the reliability of the ratings. In truth, the ’08 crisis in repo was ended by explicit and implicit government backstops. By that time: haircuts on pristine US treasuries had gone from ¼% pre crisis to 3% mid crisis; on investment grade bonds, from 1.5% or so to 10% plus. As we will see later, when there is lots of rehypothecation, those moves would matter just as much as the annihilation of triple-A CDOs. More on this later: identifying a different problem with repo is the meat of this post.

Also missing from Gorton’s picture: how much of the need for repo collateral is simply driven by the increase in OTC derivatives. According to another of Gorton’s papers, there was $2Trillion of derivatives collateral in 2007; $4Trillion in 2008. So is that why Gorton simply assumes that repo “has” to grow: to provide collateral for the OTC derivatives market? So why, then, does the OTC derivatives market have to grow? One would like to see the connection between ETFs and repo worked out by someone, somewhere, too.

Despite my whining, do have a read of the interview: here it is again. There’s plenty more, and plenty of it is good – why Dodd-Frank is a big miss, how few data are available on the enormous shadow banking system. That’s what happens when you don’t supervise financial innovations: you don’t know what they do, you don’t know how they work, and you don’t know what went wrong. If you are in full geek mode, you can download the papers that underlie the interview here and here (I must get round to that). Metrick and Gorton write about haircuts here. That lot should keep you going…

Now I’m going to double back to something that Gorton skirts: the interaction of repo haircuts, rehypothecation and the credit multiplier. Recall his interview:

If you put a dollar in your checking account and the bank has to keep 10 percent of it on reserve, they lend out 90 cents. Somebody deposits that 90 cents, the bank can lend out 81 cents (because of the 10 percent reserve requirement) and so on. So you end up creating $10 of checking accounts for $1 of demand deposits, assuming there’s a demand for loans. Now, that money multiplier process is very important because it means that the amount of endogenously created private bank money in checking accounts is 10 times the size of the collateral, so to speak, of $1 of government money. So, in a traditional banking panic, if everybody wants their $10 back, there’s only $1. And that’s the problem.

What you have here, in the equivalent language of repo, is a 10 per cent haircut, with unlimited rehypothecation (so that you can just keep reusing the collateral to raise more and more liquidity, haircutting away until the amount you can still pledge isn’t worth bothering with), and a credit multiplier of 10. To get a general picture of how the credit multiplier, haircuts and rehypothecations tie together, we now need a tiny spot of mathematics.

An aside: one of the peculiarities of mathematical economics, as opposed to mathematics, is the relative frequency of “theorems”. In mathematics, theorems are as rare as unicorn droppings, things of near-holy awesomeness; in mathematical economics, by contrast, they occur horribly frequently, like depictions of unappealing sexual acts in the oeuvre of the Marquis de Sade.

So I should probably try to get people to give this shoddily presented and deeply unoriginal formula,

![]()

some kind of grand title: Smith’s Unrestricted Rehypothecation Theorem, perhaps. What does it mean? It describes the relation between the credit multiplier under unrestricted rehypothecation, Cm¥, and h, the haircut, which is a value between 0% and 100%; k keeps count of the number of rehypothecations. Any charges levied for the rehypothecation are assumed to be negligible (I won’t keep saying this, but bear it in mind – it means that the credit multiplier is never quite as big as I say it is, though pretty close, because the charge for a rehypothecation is not huge). As you see, with unrestricted rehypothecation, you just invert the haircut to get the credit multiplier. That is the big picture.

So, as with Gorton’s deposit example above, if the repo haircut is 10%, the ultimate credit multiplier is 10. Which is to say: if you could rehypothecate for ever, liquidity amounting to 10 times the amount of underlying collateral would be created, if the haircut was 10%. Once again his polite example might be a bit misleading. Consider instead the effect of a haircut of just 1% – then the ultimate credit multiplier is 100. With zero haircuts and no rehypothecation charge, the credit multiplier would be infinite…

For anticlimactic comparison, Singh and Aitken estimate that the credit multiplier in force at the height of the bubble was about 4: there were $1Trillion of rehypothecable hedge fund assets, transmuted by the magic of rehypothecation into $4Trillion of pledgable collateral at banks. No cause for concern then? Well, that depends how much you enjoyed the ’08 liquidity crisis; and unfortunately, much higher levels of rehypothecation may be just around the corner, which is a worry.

To show why, we need another theorem, Smith’s Restricted Rehypothecation Theorem this time, I suppose. It’s just as banal as the other one:

![]()

This gives you the total credit multiplier Cmr, when you have a finite number of rehypothecations. The number of rehypothecations is given by r; h is the haircut again. As r tends to infinity, the first term on the right hand side of the equation tends to zero, giving you, in the limit, the Unrestricted Rehypothecation Theorem.

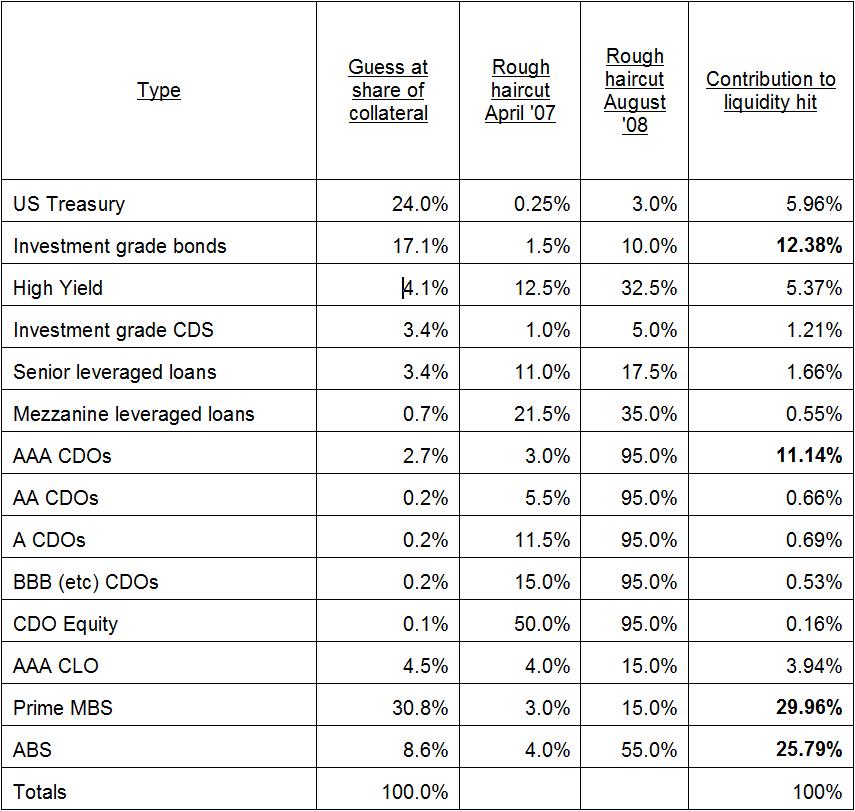

Now we can work out, for a range of haircuts, what number of rehypothecations it takes to give a credit multiplier. I’ll use the example of the IMF haircut table that Yves exhibits in ECONned (figure 9.4 there), assume an initial credit multiplier around 4 per Singh and Aitken, and use the rehypothecation formula to show the impact of the increased haircuts. The table is a bit rough and ready, but it gives an idea. The collateral has been rehypo’d on average just over three times, giving a credit multiplier of 4. Given the assumed proportion of each collateral type, the loss of liquidity amounts to $750 Billion for every $1Trillion of collateral (this is August ’08, is before the crisis got really acute).

The estimate of the amount of each collateral type involved is pretty much a guess. If only we knew! But I hope it doesn’t matter much: the table does illustrate the point that haircuts increasing from a single digit number to 10 or more, on widely held collateral (in this example, investment grade bonds, or Prime MBS), can have just as big an effect on liquidity as total wipeouts on CDOs, or big haircuts on ABS (rightmost column, in bold).

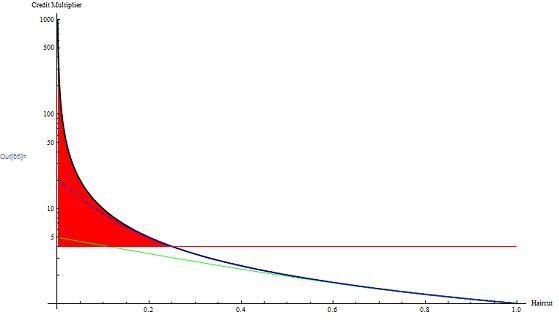

With lots of rehypothecation, it gets worse. To get a better idea of how haircuts, rehypothecation and the credit multiplier work together, it’s time for a picture of Dragon Country.

This is my two equations, graphed. Some more explanation:

- Haircut: the 1.0 (bottom right hand corner) is of course 100% , in other words, there is no repo, and the credit multiplier is 1, so there is no effect on credit. I’ve assumed the charge for rehypothecation is negligible.

- The thick black curving line shows the theoretical maximum credit multiplier when there is an infinite number of rehypothecations. On the basis that a 1000x credit multiplier is absurd enough, I stopped at 0.1% haircuts, though 0% haircuts have supposedly been used in repo.

- The unimaginable top left hand corner won’t fit on the graph: a haircut of zero and an infinite credit multiplier.

- The thin green line shows the credit multiplier for various haircuts when there are just 4 rehypothecations. You can see from the graph that this gives to a credit multiplier of around 4, for a range of haircuts from 0-20% or so.

- The just about detectable blue curve, above the green one, shows the credit multiplier when there are 20 rehypothecations: already enough to move the credit multiplier to worrying levels when the haircut is less than 20%, and when there is only a 0.25% haircut, to an absurd 17x.

- I’ve assumed that Q4 ‘08 is nasty enough for all of us, and that therefore an overall credit multiplier of 4 is as much as we want; so that’s where I’ve put the horizontal red line.

- The red area is Dragon Country, where low haircuts and lots of rehypothecation result in huge credit multipliers, and very great (exponential-like) sensitivity to increases in haircuts.

- I’ve used a logarithmic scale on the y-axis to cram the whole thing in. Dragon country would be impressively vast on a linear scale.

- The graph shows you something else Gorton doesn’t really emphasize: the only reason to like a small haircut is to maximize the amount of liquidity you create via repeated rehypothecation.

Have I just put forward one of those daft theoretical constructs beloved of economists and technocrats? I think not, for a couple of reasons.

First, “infinite” rehypothecation just sets out a limiting case that exhibits some unfortunate but representative dynamics. It doesn’t have to be that bad to be bad. In particular, the graph highlights the critical relevance to banking stability of very small repo haircuts (and by extension, collateral ratings) and the concomitant large credit multipliers. If those ratings are volatile, haircuts are volatile, and your banking system is unstable. That combination of small haircuts and large credit multipliers may be exactly what we saw in the run-up to the crisis of Q4 ’08. It did seem to be the sudden doubts about the value of “AAA” rated CDOs that caused the initial spasm of funding difficulties before March ’08 and the Bear implosion. But even unimpeachable collateral was tainted somehow. How did that happen? What’s to stop it happening again? Now add some counterparty doubts, courtesy of Lehman, with hedge funds deleveraging and then pulling their assets from Prime Brokers, which stops rehypothecation in its tracks, and by Q4 ’08 you are in a proper crisis. Even if the UK has better bankruptcy processes next time, they will get their first proper test live, in a crisis. There is no particular reason to expect a hedge fund to feel more confident about its UK Prime Broker next time we get a Q4 ’08.

Second, the doubts that have inhibited rehypothecation have been more about rights in bankruptcy than about the very idea of rehypothecation; but it’s rehypothecation that is the bogey. That’s not necessarily how the US lawmakers saw it back in 1934, when they capped rehypothecation in the US, as described by John Hempton, but the 1934 law helped a lot, anyway. Banks operated in London to get around the US restriction; then rehypothecation was a massive factor in the complexity of the Lehman bankruptcy, which dragged lots ($15-$45Bn, depending on how the bankruptcy plays out) of hedge funds’ rehypothecated assets into the mess; surviving hedge funds toned down their agreements to London rehypo, in a rush. But I suspect John is jumping the gun when he announces the end of the City of London; the availability of unrestricted rehypothecation is just too darned convenient, if you can get someone to do it. One notes that two years on, there is no UK reform of rehypo; yet there is consultation on reform of UK bankruptcy processes for investment banks, which might encourage hedge funds to agree again to unrestricted rehypothecation.

It also happens that JP Morgan, originators of those not unmixed blessings, Value-At-Risk and Credit Default Swaps, are thinking hard about how to get rehypothecation going in the grand style. They know a volume business with a cheap government backstop when they see one; they are on a marketing push, and presumably they have the systems and processes that go with it.

JPM is very keen to assure us and potential clients that the right business model (they think they have it) will be bankruptcy proof. So – unrestricted rehypo might breathe again, if enough London hedge funds can be reassured by the UK treasury and by JP Morgan.

The JPM technologists are still at work, too. Rehypothecation is getting slicker, at least for banks whose custody and treasury systems aren’t a hopeless Augean mess of underinvestment, rubbish outsourcing deals, and unmaintainability. Again, see this JP Morgan offering, for an example of what they think they can do. Presumably they think that with an implicit Government backstop, it’s OK to rehypo to the max; they have a derivatives business to support, too.

That would be a Doomsday Machine: iterated rehypothecation, huge credit multiples multiples, low haircuts, and then – sudden increases in haircuts, due to some credit shock or other. Then add some derivatives margin calls arising from the same shock…

If JPM pull it off, there will be a big credit multiplier and a big area of Dragon Country for us all to visit. Replaying the ’08 repo crash with 20 rehypothecations rather than 4 gives a system that has $17 trillion of liquidity in it, pre-crash, for every $1 trillion of collateral. Apply the crisis haircuts and $8 trillion of liquidity vanishes. That is Doomsday. All it takes is some solvency doubts; the quality of the collateral makes no difference. Indeed, because of the small starting haircuts, the US Treasuries make a larger contribution to the liquidity loss, if the number of rehypothecations is larger.

Still, the rehypo graph above, and the availability of new rehypothecation systems, and JPM’s business model, charging some fraction of a bp for each rehypothecation, do suggest ways to make sure the Doomsday Machine doesn’t blow us all up, as long as regulators get a grip.

So how does one wall off Dragon Country? The ultimate objective must be a UK version of the 1934 Securities Law, which capped rehypothecation quite effectively in the US. Pending that, or as well as, some or all of the following:

- The number of times a given piece of collateral can be rehypothecated is critical. Regulators might consider restricting it.

- Haircuts also matter, especially when they are very small. Regulators might consider increasing the minimum haircut on rehypo’d assets. If haircuts of less than 10% were not permitted, then the credit multiplier could not exceed 10 for any repo collateral, no matter how much rehypothecation there was. If it was 20%, the credit multiplier could not exceed 5.

- Regulators might consider eating some of, or a lot of, JPM’s lunch, by taxing each rehypothecation. The proceeds would build up a fund that provides the liquid assets needed in a crisis…something like an FDIC for repo liquidity.

But I wouldn’t hold your breath; the UK authorities’ response so far suggests that they, like JP Morgan, think unrestricted rehypothecation is a thoroughly good thing. I disagree.

UPDATE 7-Jan: Oops. I think this post overcomplicates things and has a big red herring (“rehypothecation steps”). From a leverage point of view, it’s the haircuts that matter. The ‘run on repo’ comes in two stages a) widening haircuts b) hedge funds pulling their assets from the PB. The effect of the run is magnified if the (London-style) Prime Brokerage agreement allows the PB to rehypothecate all the hedge fund’s assets.

If you look in my book in the section about the introduction of greenbacks during the Civil War, when national banks were also allowed to “double leverage” investments in US Treasury debt, the early modern beginnings of repo are visible. So nothing has changed, only grown larger. I suspect a lot of this could be dealt with via disclosure. I am going to write a “take apart the Fed” comment to elaborate.

WASS!

now comes another with great imaginings and rhetorical flourish

this theory need hie itself straight to the Dean’s office at every B school extant

throw out the rest, rely on the good character and verisimilitude of your associates, fellow man, and just keep on keeping on

All mumbo jumbo aside, rehypothecation is nothing but a con. It amounts to a private Wall Street money machine creating asset bubbles and periodic crashes in which no investment is safe. The bubbles permit rent extraction and the crashes demand bailouts. Leaving money in private hands under technocratic supervision is an idea whose time has come and gone. When will people wise up? Probably never.

Does anyone know how to cash in on this with relative safety? Otherwise, there is little point in discussing it.

Your Q: “Does anyone know how to cash in on this with relative safety?”

My A: Any investment banker. And they’ll tell you they’ve already cashed in with absolute safety. Not relative safety — ABSOLUTE safety.

I put Neil Young’s “After the Gold Rush” on the stereo.

FROM THE KINKS, “ARTHUR(OR THE RISE AND FALL OF THE BRITISH EMPIRE)”.

BRAIN WASHED

You look like a real human being

But you don’t have a mind of your own

Yeah, you can talk, you can breathe

You can work, you can stitch, you can sew

But you’re brainwashed

Yes you are, yes you are

Get down on your knees

You’ve got a job and a house

And a wife, and your kids and a car

Yeah, you’re content just to be

What they want you to be

And be happy to be where you are

Yes you are

Get down on your knees

Get down on your knees

The aristocrats and bureaucrats

Are dirty rats

For making you what you are

They’re up there and you re down here

You’re on the ground and they’re up with the stars

All your life they’ve kicked you around and pushed you around

Till you can’t take any more

To them you’re just a speck of dirt

But you don’t want to get up off the floor

Mister you’re just brainwashed

They give you social security

Tax saving benefits that grow at maturity

Yeah, you’re content just to be

What they want you to be

And to do what they want you to

Yes you are, yes you are

Get down on your knees

I LOVE NEIL WITH ALL OF MY HEART AND SOUL, BUT THIS ALBUM SHOULD BE THE THEME MUSIC OF NAKED CAPITALISM.

The courts may yet pour sand in the Doomsday Bubble Machine. This from Bloomberg:

Foreclosures May Be Undone by State Ruling on Mortgage Transfer

http://www.bloomberg.com/news/2011-01-06/foreclosures-may-be-undone-by-massachusetts-ruling-on-mortgage-transfers.html

Massachusetts’s highest court is poised to rule on whether foreclosures in the state should be undone because securitization-industry practices violate real- estate law governing how mortgages may be transferred.

The fight between homeowners and banks before the Supreme Judicial Court in Boston turns on whether a mortgage can be transferred without naming the recipient, a common securitization practice. Also at issue is whether the right to a mortgage follows the promissory note it secures when the note is sold, as the industry argues.

[…]

“This is the first time the securitization paradigm is squarely before a high court,” said Marie McDonnell, a mortgage-fraud analyst in Orleans, Massachusetts, who wrote a friend-of-the-court brief in favor of borrowers. The state court, under its practices, is likely to rule by next month.

Paul Revere lives!

Most of your analysis applies to a slightly different case as well, one in which there is an essentially unlimited supply of suitable collateral on the market but zero rehypothecation.

A simplified version: Suppose the brand new WeWannaRePo Bank begins life with a balance sheet comprising $C cash on the left and $C capital on the right. With repo haircuts at rate h, a corporate depositor approaches the bank wishing to take $P of collateral in exchange for $P(1-h) of cash. The bank rushes out and purchases $P worth of bonds using the $P(1-h) being repo-ed (scheduling of settlement is critical in this oversimplified version) and $Ph of its own cash. The bank can do this again and again with new clients until its entire cash stash $C is used up in this way, now replaced on the bank’s balance sheet by $C/h = $Ptotal worth of collateral on the left side and $Ptotal of repo liabilities and $C capital on the right side. The balance sheet has increased in size by a factor 1/h, and exactly the same vulnerability to a sudden change in the haircut rate is present as in your analysis, with no rehypothecation involved.

So… Once Gorton’s problem of finding a way to create vast amounts of suitable repo collateral in the system has been solved, the problem of haircut sensitivity is present no matter whether the allowed rehypothecation is a lot, a little, or none at all.

JeffC: Your insight is indeed correct, and that is the sole reason for why repo creates a money multiplier. It has nothing to do with Jeff’s bullshit argument about the # of times an asset can be rehyped.

Rehyping the collateral N times does not inflate the money supply N times. The ability to rehype simply keeps the repo market liquid, and hence lets repo deposits function like bank deposits (i.e., money).

Consider this:

A — B — C

\ |

D

Initially: A holds nothing, B holds $100 in cash and each of C and D hold $90 of cash. Total “money” = $100 + $90 + $90 = $280.

Next: A needs to raise capital, so he issues a $100 bond which gets purchased by B. B funds this purchase with $10 of his own cash, and the other $90 via repo with C: C deposits $90 with B, and B hypothecates the $100 bond to C as collateral.

Now: A holds $100 cash, B holds $90 cash, and D still holds his $90 in cash. Total “money” = $100 + $90 + $90 = $280? Wrong. C holds $100 in bonds, securing his $90 deposit at B, which C thinks of as his money (just like you think of the deposit in your bank account as your money). Total “money” = $100 + $90 + $90 + $90 = $370. It has been inflated by $90.

So what happens if C now repos the bonds to D? Well, D deposits $90 cash with C, and C transfers the $100 in bonds to D. Money supply? Lets tally. A still holds $100 cash, B still holds $90 in cash, C hold now holds $90 in cash from D, and D holds $100 in bonds securing his $90 deposit with C. Total “money” = $100 + $90 + $90 + $90 = $370. But what about C’s repo deposit with B? Well, C pledged away the $100 in bonds securing that deposit, and so cannot access those funds without first repossessing those bonds for delivery back to B. So this is longer really part of the money supply. C cashed this out when he pledged the bonds to D for cash. So the money supply has not changed.

Now what if D repos the bonds back to B? And B repos them back to C? And C back to D? And D back to B again? This can continue ad nauseum, but it is not inflating the money supply by a single cent. In order to actually access their cash, the repo lender must deliver the collateral back to the repo borrower. And you need possession of something before you can deliver it.

It is only the initial transactions between A — B, and B — C that inflate the money supply from $280 to $370. The remaining transactions are simply sloshing funds from one account to the next.

My little diagram did not render well. My graph edges meant to connect nodes A–B, B–C, C–D, and D–B. Hopefully the explanation is clearer.

And by “Jeff’s bullshit argument’ I meant “Richard’s bullshit argument’ aka “Smith’s Restricted Rehypothecation Theorem”, which was presented without any justification. And yes, I realize it is a sum of a geometric series…but so what? The terms of the series that converge to the money multiplier come from the number of times that new leverage is created in the system (i.e., the initial transactions in my toy example), not the number of times that collateral is rehypothecated.

Thank you for that fine elaboration! Viewing the time of death of the rehypothecation argment as a stopping time with respect to this comment stream, I think we can say that the process is now stopped!

Nice dissection chaps. Partway through my head scratching I think I agree; from the point of view of leverage, it’s the haircuts that matter, pure and simple; then London style rehypothecation gives access to a big pool of assets to borrow against, that the PB doesn’t even have to own in the first place, so you get huge leverage on capital that isn’t yours and can suddenly get pulled away. My stuff about rehypothecation steps isn’t to the point.

My overall conclusion will stand but I haven’t argued for it terribly well. I’ll have to get round sometime to a mark two post on this, with the fluff removed.

“how come B is allowed to use the funds borrowed on repo, but A isn’t?” should read: “how come B is allowed to use the funds borrowed on repo, but C isn’t?”

Notice that B was allowed to transfer borrowed funds to A without taking the collateral back from C. That is this sentence: “In order to actually access their cash, the repo lender must deliver the collateral back to the repo borrower” clearly did not hold in the first transaction between C and B.

Arrgh. This comment should follow my comment below.

I don’t get your logic here. What prevents C from using the funds borrowed from D to purchase a new $90 bond from A, just like B did in the previous transaction. How come B is allowed to use the funds borrowed on repo, but A isn’t? Is there a legal or accounting norm that you’re talking about here?

Taking these questions one at a time…

“What prevents C from using the funds borrowed from D to purchase a new $90 bond from A, just like B did in the previous transaction.”

Nothing prevents C from doing that. That is the point. Repoing the bond to D has freed up cash for C, so that (if C desires) he can purchase a freshly issued bond from A. C would only need to fund 10% of this, and could finance the rest by repoing the newly originated collateral. This would be just like the A–B, B–C transaction pair in my example, and would add leverage to the system and thus inflate the money supply in the same way. This is the point I am making. It is transactions like this (originate & then repo) that create the money multiplier, not the # of times that that law allows you to rehyp a single piece of collateral.

“how come B is allowed to use the funds borrowed on repo, but C isn’t?”

Please read the example a bit more carefully. B was a repo borrower, he pledged a bond and received $90 cash secured by that bond. He is free to do whatever he wants with that cash. C was both a repo lender AND a repo borrower. First C LENT $90 to B, and received a bond as collateral. C now has no cash in his pocket, but C has $90 on deposit with B. If C wants to spend that $90, C simply needs to return the bond that was pledged to him back to B, and B will return his $90 cash. But C doesn’t do that. Instead, C took that bond and rehyped it to D, who gave C $90 cash in return. The question is, how much “money” does C own? $90 or $180? The answer is $90. He has $90 cash in his pocket, and technically $90 on deposit with B. But C cannot withdraw that $90 from B unless he returns the bond, which is currently in D’s possession. If C wants that bond back, C can choose not to roll his repo arrangement with D. So D will return the bond to C, but C will then have to return to D the $90 cash that he borrowed (plus interest, but am ignoring that in my example). So now C has the bond, which he can return to B and get back his $90 on deposit. But he no longer has the $90 that he previously borrowed from D, so C can never control the full $180 at any given time. So he doesn’t “have” $180 worth of money. No money is created by rehyping collateral. That is the point I was making.

Okay. I see what you mean now — and that it addresses the post above, but I don’t think the distinction between “originate and repo” and “repo” is particularly meaningful in and of itself, since the availability of funds via repo may affect (in fact looking at the IB balance sheets, probably did affect) the amount borrowed/origination of loans.

Your claims about the money supply also confused me, since it seemed to me that you were claiming that there is no repo multiplier. In your example repo doesn’t affect base money (M0), calling repo borrowings “deposits” to create an estimate of M1 seems a bit of a stretch to me, and the channel by which repo creates an M3 multiplier seems to me to be precisely because it induces a proliferation of “originate and repo” (in the same way that a money injection into a deposit banking system induces a proliferation of deposits. And which you acknowledge is possible in answer to my first question).

‘in mathematical economics, by contrast, [theorems] occur horribly frequently, like depictions of unappealing sexual acts in the oeuvre of the Marquis de Sade.’

A telling turn of phrase, redolent of boarding schools and birch whips …

Richard,

A little help please. Hypothecation is the pledge to deliver specific collateral usually in consideration of the receipt of cash. If I’m the banker and I receive your letter of hypothecation who do I tender the the hypothecation letter to so that I can get some cash? Or, who would be foolish enough to give me money for something that is a pledge to deliver something which I don’t possess?

Now as the hypothecation letter specifies specific assets, and the initial contract is a specifically collateralized loan, who would give me money for that contract?

My point is that what is merchantable is the loan itself, not the hypothecation letter. ‘Re-hypothecation’ is perilously close to being a fraud.

In financial markets, it’s not just a letter – the PB actually takes control of the stock – which makes it very easy to use it as collateral for another loan raised by the PB…and so on.

I’ve just noticed that the Wikipedia article on hypithecation and rehypothecation has grown a bit since the last time I looked – some of my refs above are in it – so I’m going to skive off and point you there for more detail! http://tinyurl.com/2wll4ye

When I was a young teenager, my cousins and I would play a little game.

We would find some victim, draw two circles in the dirt, and explain that one was his butt and the other was a hole in the ground.

Then we would ask where was his butt. When the victim pointed at one of the circles, we would laugh and tell each other that “this guy didn’t know his butt from a whole in the ground”!

Later in life, when someone came up with something that defied common sense, we would look knowingly at each other and declare “this guy didn’t know his butt from a whole in the ground”! The poor third party with no common sense could never quite figure out how we had come to that conclusion. So the fun continued for decades.

That experience has taught me a simple lesson. If you don’t understand the deal, it is because you were never meant to understand the deal!

Let me restate the lesson for all you college educated financial types. COMPLEXITY BREEDS FRAUD!

Hey. I’m college exhausted, and I knew that. It also works the other way, fraud breeds complexity. It’s an act of defense.

Or, actually, the fraudsters. Remember, subatomic particles act randomly, humans act intentionally.

Richard-

thanks for this article. So helpful in explaining these issues! This is the result of TBTF – the inverse of moral hazard.

Gorton’s interview was informative, but one thing I don’t understand is why he regards the demand for repo in neutral terms. It’s simply taken as a given that the demand for repo exists and was provided for by the shadow banking sector, without judging whether it serves a socially useful purpose. Firms can demand “safe” assets just like they can demand commodities, but why do the seem to want so much of it?

One use for repo is for derivatives margin.

The increased demand for repoable assets mirrors larger derivatives positions.

I smell the sulpherous odor of Blythe Masters.

“The other point you need to know: we are talking about an unregulated banking system that at its height was just as big as the regulated banking system, yet coupled to it, and apparently more profitable, though, as we now know, much riskier.”

And the regulated banking system is regulated by bankers who cede themselves advantage through the press and the governing structure of their regulatory banking tyranny: aka fascist corporate state.

Of course bankers work for SOMEBODY; guess that is where ‘god’ enters the schematic. Right?

You’ve got believers and skeptics. I’m sure they’re wired different. So we’re back to religious wars. Thirty years ago I saw on overpass graffiti; “Damaged Goods Rule” progress is slow.

What we have are clay feet.

In the end will we all be converts to the universal, er catholic, liquidity: like Jeb Bush? No risks there, right?

I have to give Gorton and Richard good marks for reidentifying the uncontrolled money supply that the repo and derivative markets gave us.

A basic problem is that any ratings at all were given to derivatives. Derivatives violate the fiduciary duty of the investor on their face. This should be made a legislated point of law while case by case this goes through the court system. The ECONned ratings of derivatives is key to the whole fiasco.

We have the 600 Billion dollar stable value fund industry, who invest across a spread of ratings. This was just another CON co conspirator of using bad ratings.

We have the 3 Trillion dollar securities borrowing industry, which can not borrow shares to deliver to short sellers, but just “borrows” securities so the industry can get a CON vigorish investing in misrated securities.

We have Jefferson County Alabama, and countless other goverment and non profit hospitals and universities buying interest rate swaps, another CON you might save a few pennies, but owe millions trading opportunity.

We have local city management trading derivatives with reporting requirements such as “once a year report to the city council”.

Finally we have the government pension plans trading derivatives trying to keep up with the high frequency traders and opaque CONned ratings of securities.

There oughta be a law.

I think you quote the key point from Gorton on repo: “meets the needs of institutional investors, states and

municipalities, nonfinancial firms for a short-term, safe banking product.…It’s a valuable innovation”

The underlying question I have is: What was wrong with bank deposits that these investors “needed” repo? The answer is, I think, simple: bank deposits were regulated and well understood products, so the costs of crises were built into their price structure — in other words, the principal “advantage” of repo is that it is a bank deposit alternative with a cost structure that does not incorporate the cost of crisis.

If your proposal were to succeed, the bankers would just look for another “innovation” that is designed to circumvent financial regulation. What we need are regulators who spend some time analyzing and understanding financial “innovations” before approving their use by regulated institutions.

The term is inquisitors.

csissoko: You could not be more wrong. Repo is a collateralized loan. Bank deposits are unsecured claims. The only thing that makes a bank deposit safe is the $250k of FDIC insurance, which is not applicable to an institution that needs a safe place to put hundreds of millions of dollars of cash overnight. Repo is a safer alternative to bank deposit because the depositor is given hard collateral, more than just a bank’s word that he will have the cash available on demand.

Martingale:

No I’m not wrong. I understand that perfectly specious argument very well, but I don’t understand how after the Lehman failure anyone has the bravado to continue to make it. You are assuming liquid markets that mean that collateral has value — when everyone who’s ever read Keynes knows that liquidity has a habit of disappearing just when you need it most. (Sept 2008 is just an illustration.)

That mass of collateral held by lenders didn’t work to protect them — what protected them was the unlimited handouts from the Fed and Treasury, including vast efforts to support repo prices (TSLF, PDCF, permission for banks to use deposits to support repo, etc.).

The fact that large market participants have the obligation to monitor their banks has been fundamental to the stability of Anglo-American banking systems for centuries. (And don’t give me tripe about how unstable they were — most British banks can trace their origins to the 18th century — that’s what I call stability — the good survive along with the system and a whole bunch of bad apples are allowed to go bankrupt.)

So what you call “safety” I call a cost to the system, because by creating the illusion of “safety” for the individual lender, collateralized lending induces these lenders to accept sorry, mismanaged excuses for financial institutions as counterparties and thereby weakens the entire system.

Please replace the phrase “most British banks” above with “the largest British banks”.

You’re right, because it is regulated it must be safe. Basel II says I need only hold 0.6% equity capital against AAA-rated structured bonds, so as a regulated bank I can lever myself up the wazu with your $100MM deposit, buying all AAA-rated super-senior tranches of subprime securitizations, while my regulators give me a nice little golf clap.

The phrase I used was “regulated and well understood products, so the costs of crisis were built into the cost structure.” Your response creates a straw man by ignoring 75% of the original argument — and yes you did successfully beat your straw man down.

No, the exact phrase you used was “bank deposits were regulated and well understood products, so the costs of crises were built into their price structure”.

A depositor at a commercial bank has no control and little visibility into what the bank does with his funds. The only 2 thing he takes comfort in is 1) FDIC insurance and 2) regulatory requirements & capital adequacy standards imposed on the bank

#1 is not applicable to large institutions who have more cash on deposit than is insurable. So that leaves only #2.

I am not saying that a repo trade is riskless. I am simply saying that it is a safer alternative to a massive uninsured & unsecured deposit at a commercial bank.

If I lend via repo, I have collateral in my possession. I am not assuming anything about liquidity or value. At worst, the piece of collateral can not be sold and has zero value. That is not an assumption, that is fact. And so it puts me in no worse of a position than if I had no collateral at all. The real benefit is that I have clear visibility into the exact asset that is backing my loan. So I can monitor it, make margin calls, and risk-manage my position accordingly.

With a deposit at a commercial bank, I am trusting the bank’s regulator to be the watchdog. With $100MM of my hard-earned money? No thank you, I’ll drop the hammer on my repo counterparty well before any sleepy governmental agency even begins to wake up to the stench of insolvency.

What you call my “straw man” is exactly what has been blowing up commercial banks on a weekly basis over the last 3 years. I believe the official tall is 325 taken under FDIC receivership from 2007-2010.

Call it what you want, but my point is rather simple.

It is also my belief that repo borrowers are much more at risk than repo lenders. A repo lender that isn’t vigilant may get slightly burned in a crisis, but for the most part these guys will make it out fine. But what about repo borrowers? Institutions that rely heavily on repo to fund their operations (e.g., Bear, Lehman)….they will get knocked the f*ck down, as their lenders all simultaneously drop the hammer, making margin calls and pulling their lines.

The fundamental problem here is one of asset/liability mismatch: firms funding the purchases of long duration assets with overnight loans that could get pulled at any time.

So csissoko, when you ask the question: “What was wrong with bank deposits that these investors “needed” repo?”….I say that you are asking the _wrong_ question. I believe I’ve made the benefit of repo vs. bank deposits abundantly clear, from the investors standpoint. What you should really be asking is: what is wrong with _term funding_, that these investment banks needed to fund such a huge chunk of their balance sheet via repo? The answer to that is plain and simple: cost. You don’t make a spread by buying a 30y mortgage bond and funding it with long-term debt….”And getting killed? Maybe, maybe not! It’s

one chance in a thousand, ‘but nobody blitzes like the Shark,’ right, Tony?”

I don’t buy that there are “only two things” a depositor can “take comfort in”. The whole point of having limited deposit insurance is to force large depositors to select their banks by monitoring their balance sheets themselves. When the large depositors are worried about a bank, they can move their funds to another one. This is a very important function of large depositors in our financial system, because it ensures that banks with sound balance sheets (and remember that there’s an abundance of public information about depository institutions) will get far more money than those with weak balance sheets. You are assuming that this dynamic (which was deliberately built into the FDIC system) does not exist, and I’m not sure why.

Re your “straw man”, I agree with you entirely that the banks are not well regulated — but I think that one of the signs of the failure of regulation is the proliferation of repo.

“It is also my belief that repo borrowers are much more at risk than repo lenders.” But this is precisely my point. With repos the regulators are just creating another type of asset (not dissimilar to your superseniors) that requires them to regulate banks’ behavior in ways they don’t understand — and I expect it to take them at least a century of crises to figure it out.

If you’re arguing that we need repo to make the finance of 30 year mortgages viable, well, I think it remains to be demonstrated that 30 year mortgages are a viable product for any financial system. It seems that most such long-term obligations work well for a generation or two only to blow up at great cost on the next one.

Yes, depositors can certainly monitor their institution’s balance sheet to the best of their ability. But there is only so much comfort you can get, when the majority of the assets are banking book / held-to-maturity. The question of solvency is not an easy one to answer.

My simple point is that having a specific asset held against your loan that is marked-to-market daily leads to tighter risk management on the part of the lender. I have never heard a lender complain that a borrower has burdened them with unwanted collateral and are masochistically subjecting themselves to haircuts & margining agreements.

I am not arguing whether or not repo transactions contribute net value, stability, or instability to our financial system as a whole. I am simply saying that from the perspective of a large depositor, I understand why it makes sense over a bank deposit, which was your original question.

Perhaps my original question was not clearly phrased to begin with, but for me the question is: Why did regulators buy into the claim that investors “needed” repo? I was taking issue with Gorton’s original claim that repo was a valuable innovation because it met the needs of investors for a short-term, safe banking product.

My simple point was that it remains to be demonstrated that it’s a good idea go give institutions with more than a $0.25 million to invest anything safer than an uninsured bank deposit. We have central banks that have the tools to deal with the liquidity crises created by deposit bank failures.

Creating a new, supposedly safer, asset just creates a new kind of liquidity crisis that central banks aren’t well equipped to deal with — and more importantly haven’t developed means of charging investors in those assets for the services the central bank will provide when a liquidity crisis involving that asset takes place. Therefore, we can be sure of one thing: these “safer” assets are underpriced.

If the Fed plans to provide repo markets with liquidity in the future, then surely it should levy some kind of charge like a penny per $100 of repo to cover the costs of that insurance and its administration.

“We have central banks that have the tools to deal with the liquidity crises created by deposit bank failures.”

The fed conducts most of its OMOs through repurchase agreements with the PD banks. Repo is the primary tool used by the fed to deal with liquidity crises. It is a secured loan, I don’t understand what you find so distasteful about that. The fed refuses to lend to PDs on an unsecured basis, and for good reason.

“Creating a new, supposedly safer, asset just creates a new kind of liquidity crisis that central banks aren’t well equipped to deal with”

Repo is not new! It’s been around for nearly 100 years, since the inception of the federal reserve system. In fact, the fed was the first to trade in the repo market. Being that it invented it, I’d say yes, it is very well equipped to deal with panics associated with it. I don’t understand why you think repo “created” the crisis. Institutions need to lend to eachother, if not by repo then by some other means. Do you think the events of September 2008 would have unfolded differently if repo lending were replaced by unsecured deposits? If anything, depositors would have pulled their money faster and harder, owing to the greater opacity & uncertainty around what toxic junk could be backing their deposits.

“If the Fed plans to provide repo markets with liquidity in the future, then surely it should levy some kind of charge like a penny per $100 of repo to cover the costs of that insurance and its administration.”

If your suggestion is to put a tax on lending to keep leverage in the system down, fine. But to just beat down on repo like a redheaded stepchild, I’m sorry but I respectfully disagree.

There’s a big difference between repo for the use of the Fed and repo for the use of the private sector. Basically there has been increasing use of repo by the private sector since the 70s. The reason that it is used to such a large degree is because it is product that, since the 80s, has been permitted to do an end run around the bankruptcy law dealing with secured loans.

I’m not about to say that the Fed shouldn’t use repo — but I consider the Fed an exception, because the Fed literally can’t go bankrupt, so the questionable aspects of repo don’t really apply to the Fed.

“Do you think the events of September 2008 would have unfolded differently if repo lending were replaced by unsecured deposits?”

Absolutely, especially if you include other forms of collateralized lending (i.e. OTC derivatives) in your hypo. I don’t think that the financial institutions would have been willing to lend to each other nearly as much as they did, if it hadn’t been for their ability to pretend that they were not exposed to their counterparties because they held collateral.

In the absence of repo and collateralized derivatives, I don’t think Bear Stearns would have failed — much less Lehman — because there wouldn’t have been anyone willing to give them the rope to hang themselves with.

Dodd-Frank establishes an Office of Financial Research that is explicitly empowered to collect this kind of leverage data from the major financial players.

I can’t understand any of this, but it seems obvious that if JPM wants unrestricted rehypothecation, or anything else for that matter, it will be deadly to the rest of us.

A simple rule: If the banks want it= Bad.

No MBA needed.

Great article, thanks a lot. I enjoyed Gorton’s interview and thought he made a good point about finding better measurments.

I don’t know how far anyone (including JPM) can get with ‘rehypothecation 2.0’ except to say that finance is going to conjure some or another kind of liquidity machine out of thin air given the time to suspend the collective disbelief of its ‘clients’.

Isn’t Gary Gorton just looking for his next consulting client? I find it hard to take him seriously after his AIG experience. Does he have any sense of shame?

Repos with rehypothecation resemble fractional reserve banking in many ways. Collateral is somewhat analogous to reserves. A haircut is similar to raising a reserve requirement. When Gorton talks about needing NFBs to provide adequate collateral, he’s in effect stating that we need the equivalent of a central bank to create (or allow for the creation) of bank reserves.

I think he’s failing to see the forest for the trees though. It’s as if there were a rash of gas station fires caused by people smoking while filling up their cars, and his solution is a tighter fitting rubber boot on the gas nozzle to keep the vapors from escaping and reaching the cigarette. Yes, that solves the immediate problem, but it isn’t going to prevent gas station fires. You need to stop people from smoking at gas stations.

Having NFBs generate an unlimited amount of good collateral to support repos fixes just one problem, not all problems, and is actually certain to create new problems. Obviously.

“You need to stop people from smoking at gas stations.”

that’s communism!

my quibble:

Where are the Super Senior CDO tranches? They were never rated were they? If I call Moody’s and ask for a grade on a super senior, they will politely tell me to get fucked, am I right?

quibble with myself:

i have no idea what a ‘credit multiplier’ is, nor do i know what ‘rehypothecation’ is. i dont even really understand what a ‘haircut’ is.

my gut instinct that it’s a precise mathematical description of why leverage on leverage on leverage can bite you in the ass.

So Richard, that’s a refreshingly clear and cogent post on a complex matter. Graphs can pull central facts tightly together—but rarely do: here it’s well done. And what I find particularly useful in your presentation is this: thinly reserved repos are create severe systemic instabilities EVEN IN THE ABSENCE OF FRAUD. Even if every piece of collateral was golden, a normal level of claims could send and instability cascade through such a force-multiplier web. And as we now, much of the collateral was radioactive . . . .

Point of info: ” . . . The initial spasm of funding difficulties” was in July 07, but initially it was largely _between hedge funds_ and between them and the iBanks, although some/many of those hedgies were simply nominally off-the-books vehicles of the iBanks. It was only in Marcy 08 that funding problems swamped transactions between the iBanks themselves. This small difference in timing in no way conflicts with your larger points though, that thinly reserved repos were on a lit fuse from the get-go. And as you suppose, I’m of the view, too, we’ll get to relive the fireworks before any too long . . . .

The problem is that with high value accounts, the banks put that money [opm] to work on their own behalf [rehypothecation of the worst kind] and the projects that were meant to come from that money never manifest because the banks would crumble if it were actually put to use in the real world… so they don’t allow it to be.

Check in… fine.

Check out… never.

Ah but we do have a measure of money supply that helps follow the growth of shadow banking and tracks repo: M3! Oh wait — what’s that? The Fed decided to stop tracking M3 in 2006? To save $1.5 million dollars a year? Really? Hmmm, now why would they do something that stupid …