By Philip Pilkington, a journalist and anti-economist writing from amidst the devastated ruins of Dublin, Ireland

All successful revolutions are the kicking in of a rotten door – JK Galbraith

What’s the easiest way to embarrass an economist? Okay, that’s a bit of a trick question. After all, economics is a pretty embarrassing profession and there are a million questions you could put to an economist that would likely turn his or her cheeks red. You could, for example, approach your typical ‘academic of ill-repute’ and ask them if they saw the bursting of the US housing bubble coming or the unsustainable debt-overload that accompanied it – yep, that would probably do the trick.

One topic that does cause your average economist a lot of brain-bother, though, is the environment. After all, everyone and their cat cares about the environment these days, but such concern seems irreconcilable with the ‘infinite growth’ assumptions of most economists. It has long been pointed out by environmentalists, concerned citizens and the sane how, if we are to prevent global warming from melting the planet, we have to put some sort of a ceiling on economic growth and industrial development. This is a truly pressing concern – yet it appears that economists and policymakers simply cannot integrate it into their worldview.

But here’s an uplifting thought: what if History is doing our work for us? What if we are already entering a sort of ‘post-growth’ world?

A few days ago Professor Bill Mitchell – a man who I predict will turn out to be one of the most important economists of his generation – ran a piece on his blog entitled ‘When a nation stops growing’. The piece deals with the sluggish growth of the Japanese economy over the past two decades.

While most economists have been cooking up madcap schemes to reignite growth without end, Professor Mitchell took a far more interesting tack. Instead of concocting fantasies of what the world should be like, he took a glance at reality and asked a very important question: what if the Japanese economy has entered a stage of ‘post-growth’?

In his post Professor Mitchell points out that although the Japanese economy has been growing at a very sluggish rate, employment has been plentiful, incomes have been kept secure and prices have been reasonably stable. I’d also point to the fact that the manufacturing sector continues to be as dynamic as ever – Japan still produces extremely high-quality, up-to-date cars and electronics.

The key to this, Mitchell claims, is simple: public spending. Public spending has maintained Japanese living standards – and without smothering the economy in a web of bureaucratic stasis.

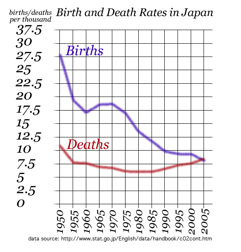

Before diving into the particulars, it should be noted that Japan went into its crisis with a significant and important demographic disadvantage. The Japanese population has been getting older for years – as this chart graphing birth and death rates make clear:

And with Japan’s draconian immigration laws, this fall-off in population has not been supplemented by a significant influx of immigrants. What can you say? Japan is an island – and there’s limited space. Just one more case for a sustainable ‘post-growth’ model.

So, keeping this in mind, let’s run through the key indicators and compare them to some of the Western economies we’ll be considering later.

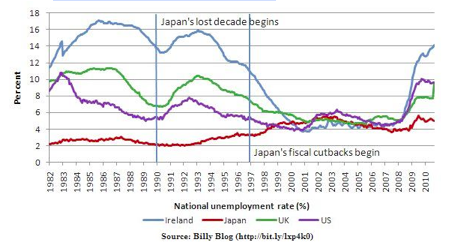

First up, unemployment. A picture says a thousand words, so here’s an interesting graph pulled from Professor Mitchell’s blog:

The first blue bar indicates the point at which the Japanese economy started experiencing serious difficulties. As can clearly be seen, the Japanese managed to keep unemployment in check rather well – even in comparison to their contemporaries who were not experiencing a bust.

The second blue bar indicates when neo-liberal fiscal cutbacks began. As we can see, this is correlated with a significant rise in unemployment. But even then, the previous spending policies managed to keep unemployment surprisingly stable.

On that graph Ireland tells the story of the so-called PIIGS rather well – a story of fierce attempts at austerity that led to massive unemployment within only a few months. The US and the UK, on the other hand, show what happens when austerity measures were less severe – as we can see the rise in unemployment is still sharp, but not quite as severe as in the case of Ireland.

Of course, all this is very rough-and-ready and there are plenty of points that would complicate this simple narrative – however, for our purposes it serves to highlight our key point rather well: namely, that the Japanese economy, while somewhat stagnant, actually held up rather well for the average person living in Japan after a major financial crisis.

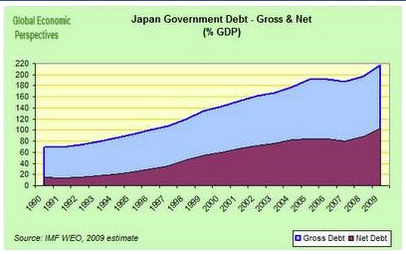

We’ve mentioned that this was due in large part to public spending measures – which are an extremely important part of the Japanese economic model. And sure enough, as the crisis worked its way through the Japanese economy and government deficits yawned open, the public debt-to-GDP ratio skyrocketed:

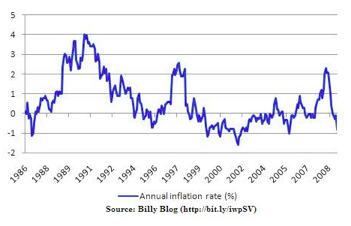

But, despite perpetual claims by the ratings agencies to the contrary, this has had few negative effects. The Yen has not become a worthless piece of paper – not by a long-shot. And hyperinflation has most certainly not taken off – indeed deflation has been Japan’s main cause for concern:

So much for internal macroeconomic meltdown. But what about social indicators? A short but precise OECD paper on social indicators published in 2009 has a few things to say on this account.

On life expectancy?

Japanese men and women have the longest life expectancy in the OECD.

On crime?

Crime levels in Japan are low. Japan has the second lowest rate (after Spain) of crime in internationally comparable data on vehicle, theft and contact crimes.

On child mortality?

Japan… [has]the… lowest rate of infant mortality [in the OECD].

The report also indicates that the Japanese work harder, sleep less and are in better shape. These, in my opinion, are more so culturally determined than anything else. But, in saying that, it would be a lot more difficult to work hard and stay in shape if you were forced to sit around all day on the dole munching breakfast cereal in your underpants

.

Overall, Japan may have had sluggish growth over the past two decades – but I, for one, wouldn’t mind living there. It’s a hell of a lot better than Ireland, I’ll tell you that. It’s probably a better place to live than the contemporary US too – unless, of course, you’re a rich financier who hates taxes and regulation.

Economists and ideologues counter these points by cribbing and moaning about inefficiency in the Japanese service sector. But, as Mitchell points out, is there really inefficiency? The service in Japanese shops and restaurants is famously pleasant and the sector as a whole seems to be keeping people employed. So, where’s the inefficiency? Another ghost summoned up by the deranged mind of the academic economist? Probably.

The economists and ideologues then claim that service sector workers need to have their pay cut – which would probably kill their smiles (economists hate smiles). And those that don’t accept these cuts should be laid off – which would create unemployment (economists hate employment). Austerity all over again.

From a common sense point-of-view – hell, even from an economic point-of-view – this appears crazy, sadistic and stupid. But of course, these hacks – who have been wrong about every important economic event over the past ten, fifteen perhaps twenty years – will then back their kooky assertions with their abstract ideas and models. In short: more ghosts. I propose that we treat these poor senile codgers as we’d treat a weird uncle at Christmas dinner; just ignore them – and if they start flicking food in your direction, ask them to leave.

Japan then should be seen as entering – slowly, gradually and with great difficulty – a new type of economic maturity, where growth as an end in itself has been buried and living standards are becoming the main concern of public policymakers.

This has very wide implications for all of us. After all, what country are all the commentators comparing the US and Western Europe to at the moment? No, I’m not talking about the crazies who point to Zimbabwe, Weimar Germany, hyperinflation and apocalypse. That’s just a rude distraction from oddball hysterics and cranks with ‘end-of-the-world’ fantasies and an inflated sense of self-importance (note that apocalyptic nihilism is almost always accompanied by grandiose messianism). All the serious commentators are pointing to the similarities between the West today and Japan after their housing market collapsed in 1991.

Professor Mitchell, for example, puts it as such:

Everyone is lining up to be the next Japan – the lost decade or two version that is.

If this is true – and I think it is – then the West too might be beginning this new phase of economic maturity. As the infinite growth model collapses in upon itself like a house of cards, Japan provides the example of what might happen next. What’s more we now have their example so that we don’t have to grasp at straws if we are truly entering into this brave new world.

For one, we now know exactly what doesn’t work: austerity. We also know that public debt – which is over 200% in Japan – is a non-issue. Ditto for demand-pull inflation.

What we need in the West is something similar to what the Japanese have implemented: policies focusing on high employment, stable prices (no, the two are not mutually exclusive) and maintaining high-living standards.

As Japan has shown, this public spending won’t cause Soviet-style economic stasis. Nor is it an act of class-war waged upon the rich (although finance needs to be better regulated – and this will require a war waged upon the non-productive and parasitic segments of the upper-class). Public debt might rise, but as we see clearly in the case of Japan, this should not be a concern – and it will probably fall again once the proper spending and taxation policies are implemented.

In saying all this, there are many obstacles. Europe, on the one hand, either needs to sort out an expansionary fiscal policy for its periphery or scrap the monetary union altogether and allow member-states to reissue their national currencies. Americans, on the other, need to overcome the strange, quasi-religious modes of ‘economic’ thought that the media and politicians spew out daily.

Then there is that scourge commonly known as the economics profession. The decrepit priests who, from their pulpits high up in academia, preach mass-suffering, resource destruction and general societal devastation as the sacrifices necessary to please their dark gods. These folks are a sort of societal brain disease – one that necessitates nothing short of a collective lobotomy. Hell, most of these folks are already drooling idiots, lopping off a slice or two of their frontal lobes will simply ensure they don’t scare anyone with their incoherent ramblings.

The challenges are considerable – although, unlike Japan circa 1991, we have an historical model to work off. But still, right now the clowns are running the circus and the tent looks set to collapse. But with History on your side anything is possible.

“a man who I predict will turn out to be one of the most important economists of his generation”

Is this an economic prediction?

“most important econonomist of his generation”

Smartest kid on the short bus.

Good post, but two points:

– Isn’t Japan’s stagnation largely the result of Zombie banks? Isn’t that what we’re seeing in the West, too? Surely that isn’t desirable?

– I’m pretty sure Japan’s debt levels are only sustainable because they only borrow from the extremely wealthy elite of their own country.

Zombie banks- so we are told by the economists.

Borrowing internally- sounds like a good idea.

Borrowing internally is not so cool because not all the Japanese lend the same quantity of money to the government.

So the government, which represents all the Japanese, owes a lot of money to just some wealthy Japaneses; in other words the poor owe money to the rich through the government.

This might be still better than outhright depression, where the poor simply starve, but still ins’t very good.

It’s a bit different in Japan because the wealthy are ‘nice’. That may sound vacuous but it is a far cry from our government borrowing from, say, the financial wealthy elite over here.

The only reason why sovereign governments, with it’s own sovereign currency’, needs to issue debt to cover part of it’s fiscal deficit is to:

a) create the facade of limited monetary funds to limit the demands of it’s population for fiscal spending

b) purchase legitamacy in the eyes of the bond market, to appear less inflationary

The effect of issuing debt to cover part if the fiscal deficit is to provide income to the creditors ( in the US, this is mostly the upper class)

From MMT theory, we should realize the need to borrow is a facade, that money us issued by the government, and that governments should not engage in the false conversation of ‘fiscal constraints’. The real issue of inflation should be controlled via taxation and sound commercial and consummers credit limiting policies.

Better than borrowing it externally and giving it to the rich, no?

I have to premise that I have a very marxist view of economics, so from my perspective wealth always flows to the rich to became aggregated capital.

From this point of view, the difference is that:

– In USA, for example, the people borrow from (say) the Chinese, and the money ultimately flow in the pockets of the american richs, but “the people” have still to pay back the Chinese.

– in Japan people borrow from Japanese richs (or upper middle class), then the money ultimately flow to the same Japanese richs, so the richs have the money and the people still owe them that same money.

In my opinion, only a very strong and fast inflation can solve the situation (inflation has to be fast because, if it comes in gradually, creditors could switch their wealth to “anti-inflation” goods such as gold, thus creating big problems).

The Japanese have an very flat income distribution compared to the US. The savings are in the hands of regular middle class types.

I stand corrected.

“they only borrow from the wealthy elite of their own country.” But here’s the point: the Japanese HAVE a country. It’s their country. In the U.S. of A., all we have is a bunch of major corporations held together by Wall Street and the international banking cartel. They’re offshoring jobs and hauling in profits as fast as they can, the country be damned.

If Americans get wise and kick in the rotten door, maybe we can build a country again, but not until.

I strongly disagree with this article.

Why does a capitalist system need growth? The reason is quite simple: in a capitalist system, most of the economic activity is controlled by a few guys with a lot of money, the “capitalists”, who invest their money in order to have some returns (more money).

If those capitalist are not convinced that they can have returns, they will not invest or employ people, thus causing a recession, unemployment etc. and possibly causing a downward spiral (since recessions lower the returns for other capitalists).

But, since capitalists will usually reinvest most of their profits, for all or most of the capitalist to have positive returns the economy needs to grow indefinitely. Note that “growth” in this sense only means growth in profits, not neceassariously in life standars or tech or stuff produced.

Hence the problem for a “post growth” economy is not that it doesn’t grow, it is that the economy is always on the verge of a recession and/or a downward spiral.

The japanese government counteracts this problem with constant stimulus, thus keeping unemployment low, but the stimulus has to be continuous; as a consequence the problem is not that Japan has an high public debt, but that the debt has to grow indefinitely, which seems impossible whatever the low rates.

Also, the low birth rate to me seems a sign that, while unemployment is low, jobs are sucky: here in Italy, whre we have had also almost a decade of no growth (but unemployment is much worse), the birth rate is also negative. The most obvious reason is that young people become often economically independent only very late, in their 30′, so that when they marry and “create a family” they are too old to have many kids (in other words low birth rate is a consequence, not a cause, of “no growth” capitalism). I believe this is the case also in Japan, where maybe young people have jobs but that jobs are temporary or very low wage so they can’t start a family and stay with theyr parents.

Hmmm… I think the author is saying that if we’re looking at handling a lower growth future (which planetary constraints may be forcing upon us), which countries might we learn from? He’s looking at Japan. What might we learn from Italy?

a) “What can we learn from Italy?” Nothing, just that low growth sucks. (also don’t elect media moghuls as premiers).

b) I think the “planetary constraints” to growth do not exists. The problem is that the author, and most economist, take for granted that for “growth” we mean real growth, with more stuff, better lifestyle etc., whereas in pratical terms what a capitalist sistems need is just a continuous growth in “capital aggregation”, or it falls on an overproduction/lack-of-effective-demand-crisis. Such crisis might well happen alsowith tons of unused resources, in fect in the 19th century plenty of crises happened, and they had obviously still lot of resources.

So you are arguing that we need to accept that the share of income flowing to the capital holders has to increase constantly, even if broad income is stagnant ? That is exactly what we had for the last decade. People don’t seem to like it much (except for a few).

No, I’m more for a “short worldwide period of hyperinflation whipes out most debt and thus most financial capital” approach.

Where “short” means 2-3 years.

I want to say something positive about this but keep getting hung up in the lack of global perspective about population, consumption and long term demand for skilled and unskilled worldwide labor. Let alone how this fits with the ongoing outsourcing by American based corporations. I don’t believe that there are enough jobs for the world going forward and racing to the bottom to put lipstick on the faces of the rich is stupid, IMO. This is where REAL economists stand up and talk about the effects of American Imperialism….oh wait, we are in polite company.

I have a real problem looking at the nationalistic fervor stirring world wide and fear it is playing into the hands of the rich oligarchy that wants to keep the focus off their ability to move finances internationally to prop up or bring down countries and otherwise keep the fear pot boiling.

I’m not convinced Japan is on a sustainable path as it is. How will it cope in few years ahead with ever so growing older population given the quoted birth/deaths chart?

With ever growing debt level % of budget to service debt will grow as well. Even mathematically it is not possible to raise debt forever.

::Public debt might rise, but as we see clearly in the case of Japan, this should not be a concern – and it will probably fall again once the proper spending and taxation policies are implemented.::

Lotsa questions rise for me here. What are those proper spending and taxation policies? What is the level of debt that will mean they have to be implemented?

All economic parameters seem to have their limits. It’s nice and even helpful to print money and run deficits but there is a limit. China and Japan won’t sell US treasuries because it will increase the value of their currency. That is until the USD declines to a certain point. Commodities can be run up to a certain point until most people can’t eat or afford transportation. Solutions that call on simply increasing debt in an unlimited amount can’t be sustainable.

Various means of debt destruction can be very useful..

http://www.nakedcapitalism.com/2011/03/satyajit-das-the-economic-calculus-of-japan’s-tragedy.html

“””Japan three problem ‘Ds’ – depression, deflation and demography – have now been joined by two new ‘Ds” – disaster and destruction. The toxic combination is exposing another ‘D’ problem for Japan – debt.”””

The hard work is trying to produce a political consensus on sustainable measures of re-balancing..

http://seekingalpha.com/article/230030-xin-faan-a-modest-proposal-to-resolve-the-coming-trade-war

“””So can we get China to fund the Xin Fa’an in America? Probably not. Muddled Chinese public opinion will be furious that desperately poor China is investing in rich America, even though the overall returns will be better and the cost of China’s adjustment will be much lower. Muddled American opinion will be furious that America is “selling out” to China. Bumptious politicians in both countries will completely fail to get the underlying economics of the trade, and they will never allow it to happen. But it is still a pretty good idea.”””

I like these little ditties from Steven Hill in the Huffington Post (via Philip Pilkington, via Billy Mitchell):

“Throughout the 1990s the Japanese unemployment rate was — ready for this? — about three percent. Not 30, that’s 3. About half the US unemployment rate at the time. During that allegedly “lost decade,” the Japanese also had universal healthcare, less inequality, the highest life expectancy, and low rates of infant mortality, crime and incarceration. Americans should be so lucky as to experience a Japanese-style lost decade.”

“This country also scores high on life expectancy, low on infant mortality, is at the top in literacy, and is low on crime, incarceration, homicides, mental illness and drug abuse. It also has a low rate of carbon emissions, doing its part to reduce global warming. In all these categories, this particular country beats both the U.S. and China by a country mile.”

THE LOST DECADE!!! … (!!!)

Too funny.

Americans consume what, more than half the world’s antidepressants? And Americans manufacture what, tacos and toxic CDS’s? And what is our leading export, I ask? Why it’s waste, of course!

I’d say the US is heading for a Lost Century, if we get lucky (no tsunamis, please).

Great post but please don’t badmouth tacos. They are excellent.

The decade was definitely lost. It was lost to all of the bubble inflating, rent extorting finance sharks. “Lost decade” certainly wasn’t as good for them as the previous one. Note who coined the term “Japan’s lost decade”. Just follow the money…

A post-growth world is not good for the environment if it has reached the limits of its ability to squeeze the environment for growth, but it’s still trying. A post-growth world is only good for the environment if it has voluntarily stopped short of the limit in order to give the environment a break.

You’re right; growth or no growth, we need to give the environment a break.

But, if nation-states continue to listen to the poison-peddlers (neo-liberal economists), and by so doing, they stubbornly adhere to the exponential growth model, then it is a mathematical certainly our environment will become — in short order, and from sea to shining sea — a toxic wasteland; fit for mutants only.

Note: Obviously, the last real hope for our species is managed contraction, but I don’t see any world leaders (bankers, corporate CEOs, neo-liberal economists, generals and marshals, etc.) calling for anything even remotely like this.

Except, perhaps, for Angela Merkel. But she is lowly politician (very lowly), and she can and will be replaced (by assassination, if necessary).

Usury (private sector finance) + steady state growth + govt. debt-based money creation = ever expanding govt. deficits. Whether or not these national debts are ‘sustainable,’ and as a corollary of that, whether or not a sovereign can ‘default,’ are discussions that fail to ask why debt-based money is necessary in the first place, just as they fail to address the systemic effects of interest-bearing debt-money on society and environment.

Because the interest owed on debt does not exist in the money supply, the economy has to grow to raise new debts to repay the interest. That is a mathematical property of interest-bearing debt-money. If the economy (effectively the Borrower in this debt-money system) cannot pay back its debts, governments choose between two options. Allowing cascading defaults to exacerbate into Depression as money supply collapses, or ‘printing’ money to sustain a financial sector which depends on economic growth as its life-blood is profit from usury. So, steady state growth plus usury means sustaining the financial sector with growing government deficit.

Why bother? Why keep this system as is? For the financiers perhaps?

At its core this system is about making money from money. By coincidence this process can be fueled by economic growth, but when that slows, stops or reverses, sustaining the system requires debt growth somewhere. “On the government’s books” is the answer MMT offers. But this is merely expanding the money supply to keep a process going for its own sake. Such a condition is mere money-growth as a mathematical consequence of usury while the economic world stands still. To me this seems at least silly, and, in that it freezes things—somewhat in an End of History manner—as they happen to be right now, is also anti-freedom, anti-change and anti-life.

So, unless discussion of mature (steady state) growth includes an impartial and scientific analysis of the function and systemic effects of debt, it is incomplete, and far, very far, from ‘anti-economic.’ For actual alternatives and open-minded analysis of these things, see Bernd Senf and Franz Hoermann. Here is a short section on banking, from a paper on the banking crisis (“Banken(-überwachung) am Pranger: Inkompetenz, Betrug oder systemische Krise?”), written by Prof. Dr. Haeseler and Prof. Dr. Hoermann, I’ve translated as best I can:

“Generally speaking, banks are run as private companies in the “free market,” that is, they are operated to make a profit. On one side of this equation, the expansion of money as loans (the compound interest business) presupposes that the money owed on the loaned and borrowed monies (both incur interest) already exists in the available money supply. On the other side, this business model can only work when the economy (the Borrower) earns, “in the market place,” a profit at least large enough to service its debt obligations (i.e. both interest and repayment of the loan!). This inflexible dynamic requires that the economy grow at a rate considerably higher than the nominal interest rate, since the credit has to be amortized too.

On top of this, banks are required to earn their shareholders as much money as possible. These monies, it should now be obvious, can only be won at the expense of their customers (savers and borrowers). Therefore, banks function as redistribution institutions systematically transferring the medium of exchange from private savers and borrowers to bank shareholders (private individuals holding bank shares, or shares of corporations which own banks).”

While money-flow from the financial sector to the real economy, via banking, takes place solely on a short term basis (after all, credit must be amortized and earn interest), what takes place is a bank-induced money-flow from the real economy to the financial sector (via these institutions’ profit earning mechanisms) at a maximally expansive rate and prolonged period (only while a bank earns sustained profits is it economically viable). With the help of the so-called Bank Bailout, however, this persistent money-flow from the real to the financial world (from the owners of real-economy businesses to owners of banks) has been, regardless of achieving formal profit objectives, continued uninterruptedly. This enforced liquidity drain from the real economy to the financial sector will likely bring about collapse in the foreseeable future. The related and grave problems we already see today (mass unemployment and shrinking pensions) will, as one might expect, drag serious democratic and political consequences in their wake.”

The high employment in Japan is, I suspect, ‘sustainable’ only in a broader context, namely, Japan as exporter to other countries as importers. How much longer can this go on, seeing as economic growth is necessary to sustain this system globally? And when it stops, what will happen to employment in Japan?

Isn’t it time we discuss seriously an alternative value system? Measuring value with a medium of exchange via the price system is no longer a pragmatic mechanism for distributing society’s produce. The endless global crises of recent decades are ample proof of this. And peak oil (and peak everything else for that matter) makes such a discussion, and action on that discussion, urgent. What we cannot afford to do, is wait until we’ve passed the tipping point.

Whether usury is a problem or not (I believe it is) certainly all government privilege for it should be removed. That would include repealing legal tender laws for private debts, repealing the capital gains tax and repealing any other legal impediment to genuine private currencies. Also, all government borrowing should be abolished. Let governments simply create, spend and tax their own fiat. However, that fiat should only be legal tender for that government’s debt not private debt.

Me likes!

Um…new definition[s of employment and ergo Jobs[?]. new reward[s?

Skippy…we can[!], although haters gonna hate, that’s the rub…eh.

Hoermann gave an interview a couple of weeks back to an internet-based Viennese TV-show, in which he lays out some of the basic ideas of an alternative system. I’ll be translating some of it in due course (it’s a long interview and he talks fast in an Austrian accent), so watch this space…

Yep, them haters will do as they do. However, Hoermann is pressing for his suggestions to be implemented first in the German-speaking world, and claims some political support from people who have yet to step forward. He also says he is but one part of a large scientific consortium which has been developing these suggestions for about 6 or 7 years now. They have only recently begun to go public.

Should their ideas gain purchase there (Germany/Austria) the world would have a model to study, inspire, fail and succeed as circumstances demand, and build upon. Right now the hard part is getting beyond the talking stage. There we, that is, humanity, needs some luck.

As outlined in the above German analysis, The critical political fact of capitalism is the the relationship between profits and accumulated capital lent back into the economy at a profit. Money is extracted from the economy as profits, and replaced, at the cost of interest back into the economy. It seems the lie of capitalism is that it is the wisest pricing mechanism when it seeks to price everything at more than it cost in the first place. Profits only exist after the transaction, and only in the form of money. The buyer gets something for more than the seller paid for all of the inputs.

People who have been systematically repopulated from a self sufficient mode of living to participate in the capitalist mode and become dependent on paying more than than an item costs, will run out of money. The capitalist thus has political power without resorting to nonsense, the divine right of kings, the will of god, the natural order of things, etc. He simply resorts to having the food, shelter, clothing, medicines that keep us alive, if we work to be paid to get what we need. Everyone understands that we need to work to get what we need. I believe that everyone but economists understand that we only work for a paycheck, because it gets us what we need, and money in a large scale complex society has utility that makes sense.

I believe that an alternative model is to learn new behavior through cultural socialization, much like language is learned and is indispensable for social organization. I believe money should be treated like language. We need language and we need money, but we need them both in the same way or we will fall into a biblical state of chaos as seen in story of the Tower of Babel. The use of money as social control is like the use of language for social control. When the printing press came to Europe and the bible was translated there was a transformation. NOW, The electronic banking we are witnessing is the most democratic and free form of money yet to be devised. However, it is being controlled by antiquated social institutions, the banks.

The radical political change over money and “the profit social control system” or capitalism, is clearly a social fiction. By clearly debunking capitalism, showing it for what it is, political control of the populace using intellectual superiority and mystification of the social order as the legitimizing process for capitalist authority, a new social fiction can be written. One that can successfully operate with civility and minimal pernicious disruptions to our everyday lives over our entire life span can be transitioned to. It can be down through the mechanism of the nation state bureaucracy, which is already in place, as Japan does. The need for political activity to gain control of that mechanism, with policies that permit for a better quality of like, as opposed for more stuff in house, that is thrown out at regular intervals, hauled to dumps and replaced with new stuff is the urgent struggle we are seeing in the world today.

This was cute at first, and then it got stupid. Japan’s stagnant growth is the result of zombie banks, but mostly due to deleveraging from the asset and housing bubbles. Richard Koo has done some good work on this.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HaNxAzLKegU&playnext=1&list=PL8957CDF74EBE6251

Growth can only stop when productivity increases stop. Productivity increases are driven by increasing the capital stock and technological advances that allow the generation of new capital. Until technology stops progressing, growth will continue.

Perhaps there are limits to growth in that we’ll use up our natural resources, but what a neoclassical economist would tell you is that when the price becomes too high people will look to alternatives. Now, there might be an argument that the transition will be to swift to be left solely to market forces, so there might be an argument for government intervention here. And then obviously in the case of global warming, but new alternative energy technologies combined with geoengineering practices could significantly reduce if not reverse this process.

Don’t forget to factor in the toxic negatives attached to all production. dust to dust.

Skippy…naw that would wreck pretty economic formulas, look over here>>>>>>beautiful profit, today[!] tomorrow will take care of its self. sun comes up, sun goes down, tide in, tide out….beautifullllll….

You wrote:

‘Growth can only stop when productivity increases stop. Productivity increases are driven by increasing the capital stock and technological advances that allow the generation of new capital. Until technology stops progressing, growth will continue.’

You need to clearly define what ‘growth’ you mean by. Increases in technological capabilty and production facilities do not necessarily result in

economic growth. In fact you could have economic contraction, inspire of technological growth…. I. E raising interest rates in the US could cause a deflationary debt spiral among consummer and commercial borrowers causing effective demand to collapse and major econmic contraction( much less real goods produced and sold),, but government agencies and private research groups might still make great progress in developing technology for alternative energy, space travel, and pollution control.

Well, let me clarify. The piece was referring to “limits to growth,” and that’s what I was referring to. Yes, “short-term” fluctuations and other factors might reverse or slow growth for a while, but by and large…

I think the main point here is that we shouldn’t confuse long-run growth with short-run growth. Japan had two lost decades because that’s how long it took to pay down all of it’s private debt and because fiscal policy was timid.

There’s a very simple macroeconomic model to deal with environmental degradation: have the government step in and make them pay!

Pilkington misreads the Japanese condition.

At best, Pilkington’s rendering is a race…and instead of “racing to the bottom”, he suggests “racing to post-growth”.

But there is no “post-growth” paradigm; it’s way too late for that. And it’s hopelessly naive to suggest that there is such a thing.

Instead, we have a “post-tragedy-of-the-commons” paradigm.

The “common parcel” has been over-grazed. Maybe…just maybe…one herder could convert from tending sheep to gathering manure. But once others join the fray, all we get are a bunch of Shit Shepards.

Japan’s pursuit of “post-growth” will only work so long as it gets to enjoy first-and-only-defector status.

At worst, instead of a “post-tragedy-of-the-commons”, it’s a “post-we’re-too-tired-to-climb-this-mountain-anymore”…

In this rendering, Japan is merely the first alpine climber tethered on a common rope to lose its footing. Sure, it’s fine for a while. It’s even quite relaxing…so long as the dangling climber is certain others won’t join him.

But, once the others do lose their footing (and they will), the situation becomes more dire.

Who’s going to hold them all up? China? Yeah, right…

they’ll just reboot with fewer people and solar panels and organic gardens.

They’ve got a lot of people for little island anyway.

When they’re half the size the are now, life will be great. Think I’ll go skiing over there and hit the saki bar, myself.

even if GDP falls by 33%, if they have half as many people, everyone will be 33% wealthier. at least. probably more than that if you include the new elbow room.

Interesting point.

Philip Pilkington said: “Then there is that scourge commonly known as the economics profession. The decrepit priests who, from their pulpits high up in academia, preach mass-suffering, resource destruction and general societal devastation as the sacrifices necessary to please their dark gods.”

This for me is the most intriguing part of economics. How did a religion, such as economics, that started out by worshiping at the altar of materialism and the maximization of aggregate utility (measured as GNP ), become just the opposite of that? Nirvana, according to this religion, was material progress, and progress was interpreted as ever expanding GNP.

In “Optimism, Pessimism and Religious Faith” Reinhold Niebuhr asserts that “human vitality has two primary sources, animal impulse and confidence in the meaningfulness of human existence.” In primitive man, meaningfulness of existence is achieved through totemistic religion which gives absolute meaning to the social group to which one is a member, giving mythical and symbolic expression to that group. Niebuhr cites Nazi Germany as a contemporary example of this, where “national loyalty is reconstructed into an all-absorbing religion.”

In spite of the fact that some men are satisfied with this “little cosmos,” it is inevitable that some men “should seek to relate their group to a larger source of meaning.” Animism is thus as primordial as totemism in the history of religion as men sought to expand their cosmos from the tribe to the far more expansive world of nature. “The gradual identification of nature gods with the gods of tribes and cities in the religions of early civilization shows how quickly the social cosmos was related to the larger universe revealed in the world of nature, and a common center and source of meaning was attributed to both of them,” Niebuhr explains. But this world of nature proved to be capricious. In addition to its glorious side there was a cruel and chaotic side, at times unrelenting in its brutality. As Niebuhr continues:

But the simple faith and optimism of primitive man did not exist long without being challenged. The world is not only a cosmos but a chaos. Every universe of meaning is constantly threatened by meaninglessness. Its harmonies are disturbed by discords. Its self-sufficiency is challenged by larger and more inclusive worlds. The more men think the more they are tempted to pessimism because their thought surveys the world which lie beyond their little cosmos, and analyzes the chaos, death, destruction and misery which seem to deny their faith in the harmony and meaningfulness of their existence in it.

So in order to escape from this chaotic world of nature, which seemed to have no rhyme or reason, men invented a supernatural world, and in this other world goodness and harmony would prevail. “All profound religion is an effort to answer the challenge of pessimism,” says Niebuhr. “It seeks a center of meaning in life which is able to include the totality of existence, and which is able to interpret the chaos as something which only provisionally threatens its cosmos and can ultimately be brought under its dominion.” In the Jewish-Christian tradition, there is an optimistic faith in a transcendent God who rules over both the natural world and the supernatural world. It is thus a turning away from the naturalistic monism of more primordial societies to theism.

During the course of the 18th century, however, we killed off this transcendent God. Man came to believe that he no longer needed a supernatural world, because he could exercise control over this world. We see this, for instance, in the Spinozistic pantheism of Jefferson’s correspondent, Joseph Priestly:

Nature, including both its materials and its laws, will be more at our command; men will make their situation in this world abundantly more easy and comfortable, they will prolong their existence in its and grow daily more happy…. Thus whatever the beginning of the world the end will be glorious and paradisiacal beyond that our imaginations can now conceive.

This superficial optimism, with its abiding faith in “progress” and with progress being measured strictly in terms of material goods and creature comforts, became the gospel of modernism. “The great wars of religion of the twentieth century were now fought among socialist, Marxist, fascist, American progressive, capitalist and other branches of an overarching religion of progress,” is how Robert H. Nelson puts it. Capitalists thus believed heaven on earth could be achieved through the market mechanism. The progressives, the “apostles of scientific management,” believed that socialist planning by a ruling scientific elite was the ticket to nirvana. For Marx, the path to the secular salvation of the world was to be achieved not through a dictatorship of the intelligentsia, but a dictatorship of the proletariat. The Russian nihilists followed this path but replaced the proletariat, which was almost nonexistent in Russia anyway, with the peasantry. And thus we see the unbridled optimism that Priestly expressed in the 18th century reemerge in a Bolshevik pamphlet of 1906 which argued that man is destined to “take possession of the universe and extend his species into distant cosmic regions, taking over the whole solar system. Human beings will become immortal.”

But of course it’s all a utopian dream, the only difference between the old religion and the new one being that, instead of utopia being other-worldly as in the old, in the new Enlightenment religion it is this-worldly. The earthly Promised Land is as much a creation of the human imagination as was the supernatural Promised Land.

Nietzsche will always be hailed as one of the greatest philosophers of our era, if for no other reason than he was one of the few to see and herald where this was all leading. Near the end of the nineteenth century he proclaimed, “Nihilism stands at the door,” and asked, “Whence comes this uncanniest of all guests? He believed that he had discovered the answer to this question in the fact that “God is dead.” And in this I think Niebuhr would agree.

And this brings us full circle back to the Austerians. How could a religion that started out with such optimism now, as Pilkington observes, “preach mass-suffering, resource destruction and general societal devastation as the sacrifices necessary to please their dark gods?” And here I think Niebuhr provides the answer:

Purely rationalistic interpretations of life and existence easily make one of two mistakes. They either result in idealistic or pantheistic sanctifications of historic reality, in which the given is appreciated too uncritically to allow for a protest against its imperfections, or they degenerate into dualism, in which the world of concrete reality is relegated to the realm of the unredeemed and unredeemable.

The best of Hebraic thought never degenerated into the dualism inherent in ancient Platonic or modern neoclassical economic thought. There exists no need to judge a world as evil, and thus deserving of punishment, which doesn’t live up to our utopian expectations. This is so because in the best of Jewish-Christian thought there exists no perfect this-world. This does not mean, however, that this world is not intensely meaningful, even though its meaning transcends human comprehension. The ethical vigor of Jewish-Christian religion comes from the fact that we are to constantly strive to come as close as we can to the moral perfection which exists in the transcendent world, even though we acknowledge can never achieve it. “In the best Jewish-Christian thought,” Niebuhr explains, “evil must be overcome even while it is recognized that evil is part of the inevitable mystery of existence. There is no disposition to declare that all ‘partial evil is universal good.’ “

Here’s the argument that population density encourages a nation to be an “exporting” nation rather than an “importing” one :-

http://petemurphy.wordpress.com/2009/03/18/population-density-vs-balance-of-trade/

So in the case of Japan not enough space for consuming big houses or space to park your two or more cars per household, RV’s or boats. Population density, however, is not the only argument playing beggar-your-neighbour export games by substantially reducing taxes like corporation tax (Ireland), rigging your currency by pegging it to your main import target (China) or providing subsidies on sales tax reimbursal (Eurozone) also affects global trade balances.

Wonderful article, loved the humorous attacks on economists. I could never understand why growth was so important. Lets see, the world is over populated, over industrialized, choking on it’s own soot. The race to the top is mostly over, the haves have and the rest suffer. Water is disappearing, soil is disappearing, and you yokels still want to argue economic theory. Spare me, Japan has developed a sustainable model, let us examine it, and take from it what we need to sustain an equally elite life style. The first point is that the 10% of GDP dept we have is not only okay, we need to spend double or triple. That would get our economy roaring. And bring down our debt. Let’s exam why this works better for us than Japan. Our farming, our manufacturing, our resource for invention and innovation. The world doesn’t look to Japan for new technology, it looks to us. Sustaining and even growing internally would be a breeze if America concentrated on that. Wake up, dummies!

This article dramatically overstates the situation in Japan. Not everything is as rosy as the author thinks.

If you look around the Japanese youths, you’ll see many disturbing sociological trends. Increasingly, young people are bouncing between part-time jobs and moving back in with their parents. There’s no longer any corporate pension or the promise of lifetime employment, which funnels labour to part time positions that are easily culled. Women are delaying marriage or foregoing it completely due to uncertain economic prospects. Men are barricading themselves (see hikikomori and herbivore men). That’s not to mention that in most material ways, Japanese are worse off than Americans. See: smaller houses, more expensive products.

Granted, Japan scores very highly on *some* quality of life measures such as health care and crime. I would argue though that it’s sustained by an isolationist immigration policy. Eliminating racial tensions goes a long way to reducing crime. Furthermore, it props up labour by creating artificial shortages where there would otherwise be unemployment.

As for health care, Japanese physicians, for cultural or language reasons, don’t make the move overseas for higher pay (as opposed to say German physicians -> US or South African physicians -> Australia). Also, the population has low obesity and smoking rates, which would go a long way to explaining morbidity+mortality vs the US.

This post-growth model can only work as long as the government can finance its spending cheaply. When/if the masses stop lending, there will be a catastrophic default or sky high inflation. Since Japan isn’t accepting immigrants, the debt per capita in real terms will only increase. There’s no hope of growing out of the debt.

about 8 years ago I briefly knew a Japanese woman in New York who worked for a securities firm.

I asked her: “If Japan’s in a big recession why is everybody out shopping and having lattes. Where’s the recession? Every time I see Japan on TV it looks like a big party.”

She stiffened up and looked down at the floor and she said “There is a rising suicide rate because men can’t find jobs. And college graduates live with their parents.”

That’s all I remember. Nothing is ever really what it seems.

The funny thing about debt is this: If I say I’ll paint your house and I die, you’re out of luck, and if you die, I get the day off. But If you sell my promise to someone else, as an abstraction, it lives after I die and after you die. It can even grow to two houses. And some sucker somewhere has to grab the roller and the paint and do them both to survive.

It’s kind of weird to think about that until it begins to make sense in the weird way it should, which it doesn’t at first.

With Japan, the people who owe will die and the people with the bonds will die, but the bonds themselves won’t die. No wonder they call them zombie banks. LOL. I never saw a tree do that.

I would think that two aspects of a post-growth economy are that it is stable and sustainable. Japan is neither. It needs to import virtually all of its hydrocarbons, and on top of this, its nuclear sector has just taken a big hit at Fukushima placing the Japanese commitment to nuclear energy in doubt. At the same time, Japan remains an export based economy which means it must compete not only with other big exporters, like China, but is particularly dependent upon world economic conditions, especially downturns in them.

Because it has so little ultimate control over its inflows (energy) and outflows (exports), I am not sure Japan is a model for post-growth.

Well, this is interesting, and I welcome the ideas. At the same time, let’s not forget that Japan is an exporter and that its stability and economic performance are not based solely on public expenditure, but also on an export-driven economy to the US and the West. The latter will need their own customers to make the Japanese model work for them, it seems to me.

”

economic maturity?

By Philip Pilkington, a journalist

”

Our greatest economic discovery is the efficiency of labour division? Does division of labour allow complexity to be negotiated by specialists within a narrow field? Does further labour division allow labourers to handle increasing levels of complexity? Complexity approaching chaos? Chaos itself? Sin embargo, can you see that economic advancement is an increase in complexity? Has our constantly increasing economic maturity reached the door of chaos? Do you hear complexity knocking on the door of chaos? Has a small measure of chaos collapsed bits and pieces of our complex efficiency? Have implosion cover-ups jammed the self-regulatory mechanisms of efficiency. Do some of the cover-ups also need to be covered? Have we reached the asymptote of efficiency benefits? Has the sound barrier exploded our hopes for higher quantum energy level?

We got trouble in River City

We got trouble with a capital T.

Just to make a quick point. I’m not saying Japan is perfect — it’s not. But the fact is that many Western countries have had a Japan-style meltdown. The point of this article is that, in human terms (i.e. employment and income), the Japanese have dealt with this better than the West have… so far. This is key: I’m NOT pointing to Japan as a utopia — I’m saying that working people have been able to keep their living-standards post-meltdown. This has definitively NOT been the case in the US, the UK and the PIIGS.

The other point is not that a Japanese ‘post-growth’ style economy is idyllic. And no broad macroeconomic model can deal directly with ‘micrological’ phenomena that cause environmental destruction. But that this is where we might be headed — and if this is dealt with properly, there might be some saving graces.

Apart from that, I’m glad people were able to read so much into the article — negative as it might have been. Thanks for your comments.

Philip,

I thought the article was brilliant. It is certainly true that Japan can be plumbed for ideas for a post-growth economy, and I believe that’s all you were saying.

What others point out, and I agree, is that culturally we are miles away from Japan here in the west — for better and for worse.

1. Japanese saving rate. Japanese don’t invest, but save in savings accounts or directly in JGBs. The US in particular is consumption-oriented. I think that has potential to change, but I’m not holding my breath. We’re conditioned to expect returns on investments, if we do invest. What the US has going for it is world reserve currency status, so should we decide to turn Japanese in this respect, we can count on some stability there.

2. Japanese suicide rate. It is the highest in the world. I’m no sociologist, but I would chalk it up to defeat and continuing occupation post WWII, as well as the “lost decade” tearing-up the social order of lifetime employment with strict vertical, age-based hierarchies. The chaos seems to spread from laid-off salarymen to their children, who see no point in imitating their parents/role models. They drift from part-time job to part-time job (“free timers”). With crushing unemployment in the US, especially among the young and recently-graduated, I’m afraid this is one trait we may pick up sooner rather than later.

3. Dearth of efficiency. In Japan, efficiency means space-conserving, and has nothing to do with business models. Here is the Japanese idea of efficiency: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=k6VUOMVKkEs

Whereas what the US (and West) does best is optimize business relationships, Japan tends to embrace long, complicated supply chains with lots of personal relationships. Official unemployment is near zero because a lot of, strictly-speaking, unnecessary people are employed. What’s different is that the US actively streamlines “human resources” and given the poor state of health care, it can only exacerbate the problem.

4. Timing. Japan could count on the rest of the world consistently consuming their exports. As all 180+ countries try to grow their way out of trouble, no one can count on exports to support the accounting.

5. As Yves pointed out, equal distribution of wealth. You’re simply expected to work hard for the sake of the team. You don’t get bonuses for valuable contributions. It’s always a team effort. Getting educated, getting old, getting married and having children are the only ways to increase your salary.

As the man said, if you’re going there (Japan), I wouldn’t leave from here (US). But here we are. As Yves and now Philip have said, we could do a lot worse than “going Japanese.”

I think the term is “freeter.” NYtimes has several articles on them.

Indeed. The freeters are supported by these phonebook-looking part time classifieds that list jobs paying almost nothing, require no skills, and have no strings attached (arubaito). While I was an intern in Japan, another intern would find furniture moving jobs in them and pick up some money that way.

Now I see “Working World” job classifieds everywhere in LA. I think Philip is on to something.

FYI on the savings rate:

http://topforeignstocks.com/wp/wp-content/uploads/2009/03/us-uk-savings-rate.JPG

http://www.tradingeconomics.com/japan/gross-national-savings-in-percent-of-gdp-imf-data.html

I often come across the ‘Japan saves a lot’ argument — and to be honest, I find it confusing.

Here’s my theory on why I think that other people think that the Japanese save a lot:

(1) They used to save a lot — pre-financial meltdown.

(2) Many might still be paying down debt — which people confuse with saving.

(3) The way the Japanese government are currently doing their spending — as I understand it — is using classic MMT means. So they issue Yen reserves and then they issue government bonds that are then bought by using the newly issued money. The large amount of bonds being issued and sold makes it appear that lots of people are saving, even though the central banks are really just issuing reserves.

Apart from that I simply cannot understand the Japanese saving myth. Perhaps I’m too young to remember when this may have been true and since I just look at government stats. Or maybe I’m missing something?

Here’s some info on the Japanese savings rate — note that I completely disagree that the low savings rate will lead to fiscal problems as the government can just issue reserves:

http://biz.thestar.com.my/news/story.asp?file=/2010/9/27/business/7107692&sec=business

“First, some background. Japan was long famous for having the highest saving rate among the industrial countries. In the early 1980’s, Japanese households were saving about 15% of their after-tax incomes. Those were the days of sharply rising incomes, when Japanese households could increase their consumption rapidly while adding significant amounts to their savings. Although the saving rate came down gradually in the 1980’s, it was still 10% in 1990.

But the 1990’s was a decade of slow growth, and households devoted a rising share of their incomes to maintaining their level of consumer spending. Although they had experienced large declines in share prices and house values, they had such large amounts of liquid savings in postal savings accounts and in banks that they did not feel the need to increase saving in order to rebuild assets.”

Of course the overall savings rate is a lot higher than, say, the US (as the 2nd chart above shows). But this appears to be mainly due to corporate savings that are amassed by taking in money from exports.

But this is not the same as the ‘careful’ Japanese saver myth.

japanese suicide rate.

How is pepetual govt spending possible? The line of credit

and/or goodwill can’t be forever? If we accept this is “forever” this public spending and it’s low unemployment,

price stability.

Income and wealth differentials still exist.

So is it a system with no mobility, a acceptance of slavery

where the master produces nothing but via our “sweat token”

“invests” continuously so the people keep working?

Is that good?

Bah and humbug.

Growth is only limited by the resources of this planet. We haven’t begun to fully tap them yet (what about all the minerals below the ocean waters? What about the gobs of power to be had from alternative energy sources?), and even when we’re well along, what about the resources of the rest of the solar system?

Insofar as growth leads us to ruin, it should of course be stopped. Whatever course leads to the maximum of human liberty, prosperity, and intellectual development must be pursued. But if there is a better way to continue economic growth, why not continue it apace?

But if there is a better way to continue economic growth, why not continue it apace? Jumpjet

Agreed!

And once the government enforced usury and counterfeiting cartel is abolished then we can move on to money forms that share wealth while allowing needed capital consolidation (for economies of scale) such as common stock.

Why people keep finding reasons to blame anything but the bankers is beyond me.

Sorry you two…but…PLEASE go study chemistry, physics, geology, something[!!!] that might give you an insight, in which you opine with such casualness. Yves links…

The scale of the effect we have on the planet is yet to sink in Sydney Morning Herald (hat tip reader Crocodile Chuck)

http://www.smh.com.au/opinion/society-and-culture/the-scale-of-the-effect-we-have-on-the-planet-is-yet-to-sink-in-20110522-1eyqk.html#ixzz1NFLy5EQB

Indeed, our impact is already so profound that my colleagues are seriously debating whether to christen this period ”the Anthropocene” – a geological epoch dominated by the global effects of our own species.

Indeed, our impact is already so profound that my colleagues are seriously debating whether to christen this period ”the Anthropocene” – a geological epoch dominated by the global effects of our own species.

To put those figures in a more sober context, we now consume energy at a rate equivalent to detonating one Hiroshima bomb (60,000 billion joules) about every four seconds and are on a trajectory towards one Hiroshima bomb every second before the end of the century.

The ocean has already soaked up so much carbon dioxide that its acidity has increased by 25 per cent since pre-industrial times and, according to recent measurements, is now absorbing heat at a rate of about 300,000 billion watts. When my students measure the temperature in boreholes across Australia, they invariably see that as much heat is now going into the upper 30 to 50 metres of the earth’s crust as is trying to get out – a result entirely consistent with the surface temperature rises measured by climate scientists.

The world’s human population has grown so much and so fast – trebling in one century and still soaring by more than 70 million a year – that it is perhaps not surprising that the vast scale of our combined environmental impacts is yet to sink in.

———-

I have lived / worked my entire life in mining, Ag, livestock, processing, distribution facility’s, CRE/RE building, civil transportation projects, sprinkled with a respite in retail. The kids that worked underneath me are now running MM$ projects globally for T1 internationally accredited company’s. Now let me use this informed position to opine.

—All human activity’s have a negative cumulative affect on the environment, full stop, irrefutable—

Discovery is NOW moving, not unlike, the financial fraud…at an exponential pace. Whilst you worry about profit and metaphysics a world is dieing, our greatness is a weapon…killing indiscriminately. And by the time these forces are apparent to even the most uniformed / inexperienced person…it will be too late. Tipping points of such mass and speed will beyond our ability once achieved.

Skippy…Too argue other wise_is to show_blatant disregard for the facts…leaving…one to wonder why, god gifted rights, individualism for the sake of self felt divinity (better than others, smarter, harder working, gifted with intellect suited to the system one operates in), endorphins brandy (fools courage). The wars of the future will not be profit based, but, too live…exist.

PS. Wife came back home after lecturing at Uni, loves trash TV. Whilst watching real House Wives of Beverly Hills, one ex-child star now married to wealthy husband, opines… *para phrasing* — I used to admire the middle class for their ability to accept their fate (mundane existence), where now I feel better about myself and my success, need to achieve life’s goals, accomplish something in life…Human greatness barf.

you ask people to believe in science, when all it has given them is dehumanizing jobs in cube farms or production lines, where they have to be mindless drones, their every movement and communication recorded and spied upon, the timing of their eating, shitting, and sleeping defined by a bureaucracy.

this is what science has wrought. science claims it is for good, when people challenge it to prove its utility. but when people try to argue that science has done bad things, like cooperate with hitler, stalin, tojo, etc, science claims that it is merely a neutral tool, and not responsible for its uses.

the greatest scientists (Einstein, Sakharov) all became raving hippies obsessed with civil liberties, the rule of law, and civil society. but go to any science education program, and try to bring up civil society, and they will beat you to death with their NDA national security contracts, rolled up in a rod like a newspaper.

science now screams the world is ending. and it wonders why nobody cares?

nobody cares because science brought us to this mess. bessemer, watt, carnegie, these are the people of the industrial revolution, which was aided and abetted by science. then let science bring us out of this dark age and prove its social utility. but do not lecture us for a moment that it is our fault.

I think this is a very important point, but perhaps more important is this question: what brought us to science?

Charles Eisenstein addresses this question very deeply in “The Ascent of Humanity” and concludes it is our ego-based sense of ourselves as separate from nature, as of nature as discrete objects bumping into each other but essentially unrelated. The “truth” is that reality is far more nuanced and interrelated, and we are beginning the painful process of incorporating this new wisdom into our culture and socioeconomics now.

In the end it is not science which is the problem but our wisdom in using it. Science is merely the striving after the next most likely explanation. It cannot explain everything in much the same way that falsificationism is not falsifiable, but, should we learn how to live sustainably and accept uncertainty, to accept that desire for total control is killing us and much else besides, science will still be a very important and potent methodology.

Science is a tool (it is old as we are, its called observation), how people use it is another thing. People brought this on, “don’t blame the tool” is an old tradie colloquialism. So ipso facto, the observations made, theory presented in itself, of the observable and measurable, is not_an act_ in its self!

Humans are *actors* not *information*, science is a means to and end, that we don’t have all the knowledge this cosmos contains but, that we wish to understand it, *if* we can.

Your diatribe is directed at humans that acted for their own reasons, in a system that rewards personal greatness over any other metric, and yet you lament a tools effect once wielded by your own species?

Look simply_put_the same effect could be achieved with stone tools / life style, it would only take longer and require more population, we live in a complex system that is ever changing but very old. Some things are the same although changes occur, this is a work in process.

Metaphysics is much older as a means to relate with our environment, humanity’s need to reconcile conflict aka fear. It affords us a seemingly resolute position by which we can move forward, unfortunately humanity for what ever reasons is predicated to leadership by force aka coercion, see scary nursery rhymes, why must I scare everyone into doing the right thing thingy?

Skippy…sorry for the wind but, I fear for us all and other things, understand your position[s. Personally I believe in *becoming* human, its just not defined by others opines that lacked better information, a task never completed…eh.

PS. action[s are not resolved in the now, its an observation on going, me hopes that we submit to the totality of it all, rather than fight for conquest it, for it will be our undoing. Be well.

I have to say that Max Plank, Jane Goodall, and David Hume would have to disagree with your theory of side effect-free observation.

For me the important question is which has the ultimate sway — science or religion? It seems we’ve replaced Christianity with Capitalism and are now dealing with the consequences. Can the bulk of humanity receive a crash course in science before we stampede off a cliff?

Ah Skippy,

Most of the damage to the environment and waste is funded with so-called “credit” from the crooked money system which btw requires exponential growth just to pay the interest.

So much (all?) of what you speak would be mute if we simply reformed the money system.

The only resource which is unlimited is information.

For human timescales, solar energy is “unlimited” in total (once the sun goes red giant, we’re toast whatever we do, so that’s not important to worry about) but not in quantity available per day (which is limited and constant).

Accordingly, the only arena in which we can enjoy anything approximating growth forever is information. We have to limit everything else: population, materials consumption, etc.; energy consumption has to be limited to what the sun provides.

I don’t think Pilkington was calling for an end to new learning and knowledge. The fact is that that kind of growth, growth in information, is simply not measured in GDP. Japan has had a lot of that kind of growth with no visible change in GDP.

Sigh. So much wrong in this article.

First and foremost, those commentators who pointed out that low growth is the result of the toxic banks in Japan and their inability to lend are correct.

Second, Japanese demographics are abysmal. Fewer workers and fewer consumers means that while average salaries may increase and consumption grows, aggregate demand is flat or dropping: duh.

Third, one of the reasons that the rating agencies haven’t trashed Japan’s rating is that the vast majority of debt in Japan in domestically financed via the Post Bank there, which is one of the largest retail banks out there. The Japanese have, historically, been great savers and their savings rate has been, over the last 20 years or so, twice to three times US savings rates. This is a healthy relationship as long as one criteria is met: that demographics plays along. Yves’ comment on the Japanese distribution of income is also correct: it is one of the flatter distribution curves around, supported by cultural constraints, a very homogeneous society and, above all, significant restraint of Japanese elites, who, largely, view earning vast amounts of money as something that is not an end in itself, but rather a means to an end.

The Japanese economy is chasing an illusion: as their citizens retire and as they start dis-saving – consuming – their savings in retirement, the significant domestic reserves that have financed Japanese government spending to date will – and are – declining, such that within the next 5 years or so, Japanese sovereign debt will not be able to be financed domestically.

At that point government spending will hit a brick wall: either it will have to finance its debt internationally or it will have to reduce its debt significantly (and I don’t mean 10%: it will have to be virtually eliminated). Given the already extremely high levels of Japanese debt-to-GDP ratio, the former will result in downgrading Japanese sovereign government debt risk ratings significantly; the latter would drive the economy into a long-term recession.

Boy, what great choices. They’re the same constraints that face virtually all “civilized” economies: at some point promises made by politicians can’t be financed. You do run out of other people’s money.

Japanese suicide rates are alarming; Japanese poverty rates among the elderly are not pretty to see (and are offset by the willingness for intergenerational living conditions by many Japanese families, something you rarely see in the West); health care, while affordable and wide-spread, is not the best (Japanese longevity has to do with genes and life-style, not superior health care, and their dentists are infamous for scheduling multiple appointments to milk the system (and you) for the maximum amount, rather than doing work in a single visit); and, finally, you cannot simply take the workings of an insular, homogenous society, with strict societal codes and regimentation, and apply it willy-nilly to other societies.

If you are living in Japan with an expat salary and company apartment, life is great (as long as you don’t expect to ever be accepted); if you are there working and living like your average Japanese, life is rather different. I’m not trashing Japan here, but rather trying to insert some reality into the discussion.

Oh, and by calling himself an anti-economist, Mr. Pilkington is showing that he is more than a little in love with economics. Too bad that he really doesn’t understand what his scenarios entail: no growth means no increases in salary, no investments to improve productivity, statism pure. No growth means no improvements in life style, no new gadgets to keep us amused, no new medications, no new technological developments to reduce energy usage.

Of course, if you say you want to allow those things, you end up with a command economy. If you don’t know how badly that ended, that won’t help you in avoiding the mistakes made that killed millions (of course, if that is your goal to begin with…).

“…such that within the next 5 years or so, Japanese sovereign debt will not be able to be financed domestically.”

Seriously doubt that. The debt seems to be financed through reserve issuance — i.e. the banks seem to be creating the money being used to purchase the debt. As the MMT folks point out, this can probably continue indefinitely.

You’re probably not going to believe me, but consider this. The ratings agencies and their chums have been giving an ultimatum on Japanese debt for years. Every two years or so they seem to push it forward. Its a bit like a fundamentalist Christian claiming that the day of reckoning is upon us and then when it doesn’t come on the prescribed date they claim that they got it slightly wrong but that their ‘theory’ is still valid and the day is now two years down the road.

The question for people who believe that the Japanese debt is unsustainable is this: how long are you willing to believe this? If it is still sustainable at, say, 350% of GDP in ten years will you reevaluate your stance? If not, then when?

I’m not going to try to convince people who believe that Japanese debt is going to melt the currency any day now, but I’d ask them to be reasonable enough to choose a date or a debt-level, write it down and stick with it. If by that time/debt-level the whole thing hasn’t fallen apart then it might be time to rethink.

“No growth means no improvements in life style, no new gadgets to keep us amused, no new medications, no new technological developments to reduce energy usage.”

I suggest that you reread the article — carefully. That goes for most of your other points as well.

From Bill Mitchell’s blog (linked in article) — which I assume you didn’t read:

“Prior to the crisis, the IMF released a paper (January 2, 2007) – Strategies for Fiscal Consolidation in Japan – which said:

Japan’s key fiscal challenge is to put public finances on a more sustainable footing. Large government budget deficits have boosted Japan’s net public debt to over 85 percent of GDP, one of the highest in the OECD … In the years ahead … the government’s net debt could rise to over

150 percent of GDP.

I could trawl back through my archives and find similar warnings when the debt ratio was less and they were claiming it would get to 80 per cent and 70 and 50 etc.

In fact, the OECD and the IMF have been going on about Japan – relentlessly – for years now and each time they proffer some dire forecast – the situation gets “worse” (by their measurements) and nothing particularly bad happens. In particular, unemployment remains relatively low and their is still a commitment to income security in Japan.”

John F. Opie missed the obvious — if retirees draw down their savings (even forced savings), then that benefits the economy enormously through tax receipts from increase in demand/consumption.

This is apropos to the US as people fret about Social Security. As retirees draw down their savings, it will boost consumption without adding anything to private debt. Hopefully a sustained increase in consumption will soften unemployment.

But in the US we’ve seen plenty of consumption in the last ten years with no improvement in employment. So the time to do something is now.

“nothing particularly bad happens”

Not so. ‘bad credit rating’ is bankster jargon meaning ‘no opportunity for looting’. The leaches on Wall St are starving.. er.. not as bloated as they would prefer.

What do you have against Japanese demographics?

A stable population with shrinking numbers is *excellent*. It’s more environmentally sound, and it means more resources for each person.

As long as the population doesn’t fall below critical threshholds where certain aspects of civilization become impossible (and it’s far from that low), *what’s your problem with it*?

Um. Also, you’re crazily wrong in your attacks on Japanese quality of life. While it’s far from perfect, their suicide rate is not notably high compared to (say) Finland or the US, the poverty rate for the elderly is not notably high compared to the US, and their health care is outrageously better than the US, with US dentists having every bad feature you attribute to Japanese dentists plus several dozen more.

Well, hey, you’re right, we could have an economic future like Japan.

Or the government could continue to choose maddeningly insane “austerity” policies combined with spending on a larger and larger police state, favoritism and scapegoating, and we really could end up like Nazi Germany (forget Weimar).