Philip Pilkington is a journalist currently sinking, together with the rest of his fellow countrymen, down into the hole in the Irish banking system

Will all your money

Keep you from madness

Keep you from sadness

When you’re down in the hole

Cause you’ll be down in the gutter

You’ll be bumming for cigarettes

Bumming for nylons

In the American Zone

–‘Down in the Hole’, The Rolling Stones

Everyone who is anyone is saying it: the US looks set to become the next Japan. Yet the particulars of the argument are never really trashed out. Certainly both countries suffer from the same malady – namely, a bursting asset bubble punching gigantic holes in private sector balance sheets. This leads to similar policy approaches – not to mention similar policy failures. But beyond this overarching comparison people tend not to tread.

Let’s start from the beginning; the asset bubbles that set off the crises.

Toil and Trouble

The housing bubble that inflated in the US prior to the economic collapse is too well-known for me to dwell on it at any length. Anyone who is not keenly and constantly aware of this phenomenon and its relation to our present difficulties should either get their head checked out or apply to The Washington Post for a job – needless to say that both options will likely land you in a madhouse.

The Japanese asset bubbles are less well-known. Note that I say asset ‘bubbles’, as there were two major bubbles inflating at the same time. There was not only a major bubble inflating in the real estate market, there was also a one being blown in the NIKKEI stock market.

The overall economic situation of Japan when the bubble was inflating in the late-80s – known as the Heisei era which, rather ironically, means something like the ‘peace everywhere’ era – was very similar in many respects to the US when it experienced its bubble-era. As this Bank of Japan report makes clear, economic growth was strong and inflation remained low.

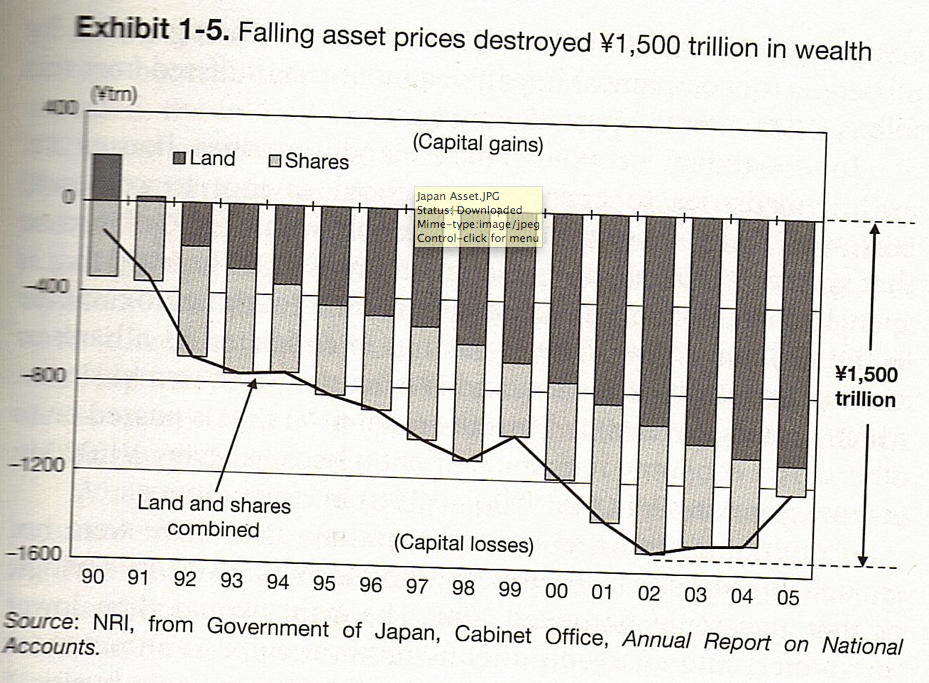

The bursting of the Japanese bubbles was devastating. In his book ‘The Holy Grail of Macroeconomics: Lessons from Japan’s Great Recession’ the economist Richard Koo estimates that some ¥1,500tn was wiped out. That, according to Koo, is about equal to the entire nation’s stock of personal financial assets at the time. It was also roughly equivalent to about three years of Japanese GDP. Ouch!

Economist Dean Baker, in his book ‘False Profits: Recovering from the Bubble Economy’, notes that the total losses from the bursting of the housing bubble will probably be around $8tn when the whole thing has finally wound down. Considering that this is just over half of one year’s GDP for the US, this seems like a far less substantial bubble than the one that inflated in Japan. This, I think, is where we see the first divergence between the US meltdown and the Japanese.

Who is saving and why?

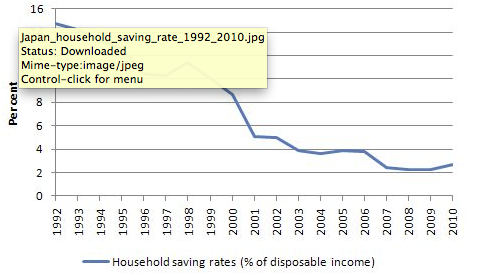

The Japanese were long known – together with the Germans – as the cautious and reliable saver-types. But after the bubble popped at the beginning of the 90s the household savings rate took a dive

The fall in the Japanese household savings-rate clearly did not lead to an aggregate rise in consumer expenditure – indeed, the country has been experiencing price deflation intermittently throughout the last two decades. Bill Mitchell – from whom I stole the above graph – indicates that the fall in saving has a lot to do with demographic issues. As the Japanese population get older, more people have begun to tap their savings.

In keeping with demographic shifts, others have pointed out that the younger Japanese generation have thrown off their parents’ ‘Protestant ethic’ and become rabid consumers. Well, that would certainly explain the shift that has taken place from a strongly ethical culture that glorifies Samurai-like principles of honour and dignity as depicted in films such as ‘Seven Samurai’ by Akira Kurosawa to… well… erm… this.

Despite this, erm, heroic drive by the young Japanese to embrace, erm, penguins and toilet-seats, aggregate demand remains sluggish and unable to pull the economy out of stagnation. There’s also the issue of stagnating real wages which is always going to put a dent in household savings rates.

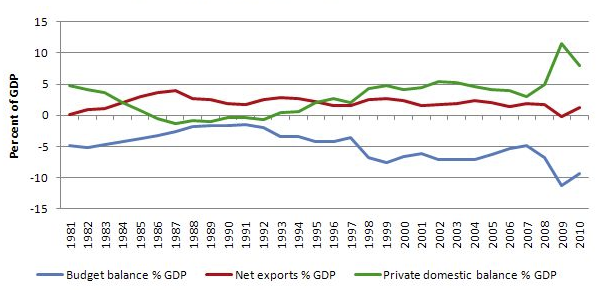

Yet despite this fall in household saving, there is no doubt that the Japanese economy is experiencing a far too high rate of overall private sector saving. Mitchell points this out using the much loved sectoral balances model.

So, what on earth is going on? Well, as Mitchell points out, while the household sector is tightening its belts, the corporate sector is retaining more of its earnings.

This is perfectly in keeping with Richard Koo’s idea that the Japanese have experienced what he calls a ‘balance sheet recession’ – that is, a recession that is caused by companies retaining their earnings in order to pay down debt. This leads to a drain on reinvestment.

The expansion of government debt (see: sectoral balances graph above), then, was the only thing keeping the Japanese economy from falling into a protracted depression.

Okay, so that’s what happened in Japan – but what happened in the US?

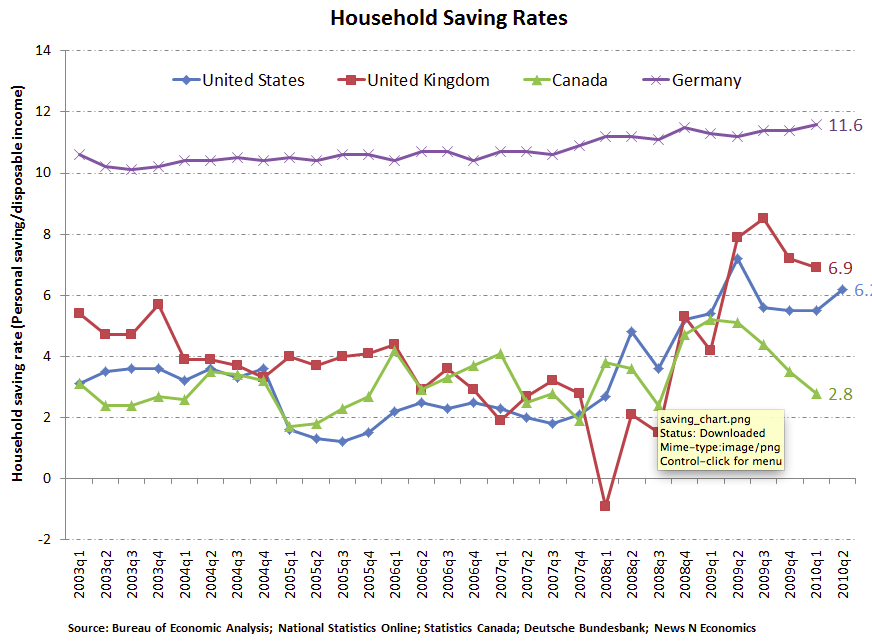

Well, after the housing bubble burst in the US the household savings rate climbed up from the quagmire it had been in for years beforehand. (Apologies for the cluttered graph – I’m completely inept when it comes to making my own; a typical symptom of Blogitis).

This is the exact opposite of what happened in Japan. Prior to the crisis Japan had an extremely high-rate of household savings. The US, on the other hand, went from a desperately low level of household savings to a higher one.

Unemployment also rose significantly in the US – which did not occur in Japan.

However, similar to Japan the government deficit opened up in the US to offset the higher level of net private sector saving.

So, we do have many similarities between the US and Japan – both experienced crisis after a significant asset bubble crashed out and both have high-levels of net private sector saving which require government deficits to offset. But there are also differences.

If I were to sum up this difference – giving myself room for the sort of crass generalisations that ‘summing up’ always entails – I would say that the US’s current slump is more so driven by demand-side factors, while Japan’s is more so driven by a ‘balance sheet recession’ on the part of companies. The US has seen a pretty straightforward collapse in private sector demand – with unemployment rising and the household sector net saving. Japan, on the other hand, was not hit with a wave of unemployment and household saving actually fell significantly; indeed, their problem was tied to the companies desperately paying down the debt they had incurred after the asset bubbles collapsed.

What is to be done?

Richard Koo claims that the Japanese ‘got it right’ when they allowed the government deficits to open up. This allowed indebted companies time to get their balance sheets in order. Bill Mitchell largely agrees. While Martin Wolf, in an article written in the Financial Times last year, agrees for the most part but claims that Japan has other underlying problems related to opportunities for investment (I’m not going into this here – although, and I’m rather surprised to say it, I think you can derive broadly similar conclusions from Wolf’s argument as yours truly did from Mitchell’s regarding Japan’s future trajectory).

So, there’s quite a bit of consensus among serious, non-hysterical types about the approach needed to fix the Japanese problem: high-levels of government spending to facilitate the private sectors net saving desires (in this case: private-sector deleveraging).

That means that when Mr. Jagger asks “will all your money/keep you from madness/keep you from sadness/ when you’re down in the hole”? We can answer pretty definitively: yes, yes it will. The government certainly does need to create new money to keep the US from falling any further down the hole.

There is one other argument that is worth considering. One able representative is occasional NC writer Ed Harrison. I like to refer to this as the ‘smash the technostructure’ argument. The idea is that there is too much overcapacity in Japan and bankrupt or ‘zombie’ companies need to be allowed to fail.

I think this argument – which I think is more so moral than economic – is both naïve and destructive. Modern industrial economies like Japan and the US are not made up of small businesses with minor capital outlays that can easily be replaced by others that spring up when the ostensibly rotten ones fail. Instead these economies are, to a significant extent, dominated by huge corporations that are structured entirely differently to the small business of neoclassical and Austrian lore.

These are the entities that have incurred huge debt-loads and find it difficult to function while Japanese consumers have inadequate resources to purchase their wares. If the Japanese were to ‘smash the technostructure’ – which would be politically impossible anyway – the result would probably be mass unemployment and a serious economic depression.

To drive this point home because, conflicting as it does with market-mythology, I fear it will be lost on many: Corporations with mass capital outlays aren’t formed by heroic entrepreneur-types overnight. They are highly evolved social institutions that take much time and collective effort to build. If these are destroyed you would likely end up with a sort of ‘cowboy capitalism’ filling the void; a system geared toward short-term profit – perhaps even criminality – rather than long-term growth and stability. (Something broadly similar happened in Russia after the fall of Communism but for different reasons – which ‘shock therapy’ then exacerbated).

But as we have highlighted, the crisis in the US, while similar to that in Japan in many respects, is not quite the same. In the US the problem is more so to do with unemployment and stagnant aggregate demand. So, even if the ‘smash the technostructure’ argument wasn’t completely poisonous, it would still be inapplicable (unless of course, you substitute ‘zombie’ companies with ‘zombie’ banks – but that’s another argument and another story).

This probably means that the fiscal solution is even more applicable to the US than it was to Japan. While the Japanese economy needed to be kept on life-support for a few years while they got their collective house in order, the US citizenry just need more bucks.

As Martin Wolf points out in another piece back in 2009:

“The big US debt accumulations were not by non-financial corporations but by households and the financial sector.”

Wolf goes on to highlight the skyrocketing debt incurred by the financial sector throughout the period. What he should be highlighting is that, more often than not, fastened to the end of the financial sector’s debt-chain is a low to medium-income human being. And that is where most of these debts ultimately land. That, in turn, is why this is, when we strip away the complexities, a fairly straightforward crisis of aggregate demand.

Households have been pushed into debt because their wages haven’t been allowed to keep pace with productivity growth for decades. Add to this the maniacal desire that possessed certain Democratic administrations to run budget surpluses in relatively good economic times and you’ve got a pretty explosive mixture.

So, it’s clear that the US citizenry need more bucks; but where should they get them? Why, from the government of course. After all, they’re the only realistic source right now. They can do this either through tax-breaks – for the working man, NOT for the rich – or some sort of employment program (I favour the latter, but I recognise that the former is probably more politically realistic).

“Yippee!” cries the Yankee Doodle Naked Capitalism reader. “We’re not nearly as badly off as the Japanese were a few years ago; this’ll be easy.” Not so fast. The US is probably in a much worse position than the Japanese were back at the beginning of the 90s. Why? Eh… because crazy people run the country… duh.

Pete Peterson and his cronies stalk the halls of government spreading lies and nonsense. Fox News runs a ‘debt clock’ (even though half their presenters probably don’t understand what the word ‘economy’ means). US populism consists of standing on a soapbox calling half the population baby-murderers and then expecting people to take your gold-under-the-mattress economic ‘analysis’ seriously (which they then do, because who on earth would trust a ‘baby-murderer’?).

The US government isn’t going to undertake active fiscal stimulus without a major shift in the terms of debate. But that is perhaps one of the most difficult things to accomplish. I’d suggest you start by closing down loony-bins like The Washington Post while retaining their facilities to ensure that your current policymakers receive adequate care and treatment. That should also make for a couple of new public sector jobs in the process.

Until the vampire squid is ripped from our faces, and repeatedly ripped off as it cannot be removed and killed in one fell swoop, than any attempt at increase in production or efficiency is simply a method to work harder to provide more to the squid.

Our problems are systemic, built over decades. Stimulus without MAJOR reform is just wasting time, money, and killing the savings of those who have worked hard and innovated. That will kill the incentive to work hard and innovate. Fairly simple actually. Remove the Squid. Stop every type of lobbying and campaign contribution. Limit election spending to dollar amounts, set it for each type of election. Remove the Squid.

That is the beauty of the Mediterranean Mêlée at the moment. Vigilantes are learning how to remove the sucker. Some of people are fighting for their very lives. They are learning to fight. They are learning to die a noble death with the fire in their veins. They are leaving something for their families, something that will not be forgotten. Have we forgotten George Washington? Can we be resourceful? Can we fight for our lives? For our Country? I think we can do it.

No offense philip, but you a. don’t prove what you promise to do given your title, and b. you ignore rather a lot of the relevant considerations (differences in culture, gini, total savings going into the crisis, how savings and debt are distributed across the sectors and why this matters, what difference the fact that the US is an import economy while Japan is/was an export economy makes, employment rate).

You sort of mention aggregate demand and cultural issues at the end, but you don’t really do anything with them other than to note that the median income probably needs to rise. But especially the ‘cultural’ factor is huge, while the impact is hard to discuss precisely because of that. Economists (and economic analysts) sometimes like to pretend that culture is the fluff that determines which color of Levis you buy, but that is missing the point entirely. For instance, the fact that Japan had had the same party ruling it since WWII — heavily intertwined with the corporate sector, and with a strongly felt duty to keep the standard of living for everyone up — is part of that, and is hugely important to explain the differences in approach. Yet all you say about it is that “crazy people run the US”.

And as to the fact that what I hint at above wouldn’t have fitted in an article this size: yes, but that is my point.

And a last point: the problems in Japan did not start with asset bubbles. The problems started when there was too much money floating around to be profitably invested. No sane investor is going to invest in RE or land when there is still a large amount of profit to be made by investing in growth (this is a double problem: the amount of money available for reinvestment compounds yoy, while the amount of growth possible decreases the more developed an economy becomes). This led to asset speculation, and thus the bubble(s).

I briefly mention that Martin Wolf raises that point but say that it would be too much to go into — I also point out that such a point would broadly tie into a previous post I made about Japan.

Yes, but as you yourself note in your response to TJ, there are quite a few relevant differences between the US and Japanese bubbles; as such, it is not a necessary starting point. And it is my suspicion that you would’ve been in a much better position to discuss the other relevant differences (the ‘cultural’ and political ones I refer to above) had you done so.

Foppe: these criticisms are understandable, but I was a little surprised that you didn’t take Philip to task for an idea that he actually did spend a little more time describing – the supposed naivete of Harrison’s creative destruction alternative, or “smash the technostructure”.

I actually went and read Ed’s piece, and as written, it was a little simplistic and not nuanced enough. However, in reading Philip’s attack, it is easy to see that line of argumentation devolve into a soft defense of big corporate fascism. I couldn’t help but be reminded of the various TBTF bank pleas and the similarities here. And that’s what we need to call out, because I sense that many readers (and voters) alike are getting very tired of this meme.

So what to do? I emphasize that the thinking needs to evolve beyond a simple ‘let em fail’ or ‘prop them up for the protection of the many’. As an example, my criticism of Ed’s piece is that he should be describing specific, post big corporate failure actions that would quickly restart new viable companies and/or mitigate the economic loss of the newly unemployed – and acknowledge that there will be *some* pain yes, but that over the long haul, this will be worth the cost of preventing a fascist structure that has potentially worse outcomes.

Philip, be careful throwing out things such as “there will be cowboy captilism” or “increased criminality” so loosely. It’s obvious you are concerned with many of same things that readers are here, but you will wear your credibility thin if you let yourself knee-jerk protect the real threat – which are the big, poorly run, and sometimes unethical/criminal large businesses…

I have no love for big corporations. But they are central institutions in modern economies. If you just trash them, it’ll create an enormous vacuum.

In Russia people thought that they were tearing down the old institutions of power — the corporations created by the Communists. In reality all that was happening was that a bunch of corrupt asset-strippers were wrecking the economy and putting people out of work.

People need to be very, very careful about those who speak the words of revolution but really just want to turn a profit. Sometimes people that appear to be your allies are no such thing.

Sorry, but that isn’t true at all. Naomi Klein:

I don’t understand how that contradicts what I’m saying. Maybe the Russian people were less happy with the shock therapy… is that what you’re saying?

Okay, maybe that’s true. I’ll be more specific:

A lot of people — in power and in the media — assumed that what was happening in Russia was a tearing down of the old Communist power-structures. But what was really happening was that a bunch of asset-strippers — soon to be called ‘oligarchs’ — were tearing the economy apart.

I have no love for big corporations. But they are central institutions in modern economies. If you just trash them, it’ll create an enormous vacuum. PP

There is nothing inherently wrong with corporations as there is with banks which are a government enforced and backed counterfeiting cartel.

And once the banking cartel is abolished then corporations will be forced by economic necessity to share wealth with their workers rather than loot them.

Philip,

I think you statement

is one of the best short explanations of what has had happened with Russia.

This was a modern variant of Nanking rape (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nanking_Massacre), only the rape was economic and the invading force has help of fifth column within the country. It was cruel beyond any imagination.

It’s a tragic fact that the West looked at Russia which get rid of communist rule as a bounty in Cold War and behaved accordingly. And now those jerks complain about Russia being non-cooperative. Clinton’s behavior was especially criminal and that damage will last for a long time. But colonization of this economic space has it’s benefits and it helped to lift the USA economy from the recession and ensured the boom that lasted till 2000.

See Testimony of Anne Williamson

before the Committee on Banking and Financial Services of the United States House of Representatives

September 21, 1999 htttp://www.thebirdman.org/Index/Others/Others-Doc-Economics&Finance/+Doc-Economics&Finance-GovernmentInfluence&Meddling/BankstersInRussiaAndGlobalEconomy.htm

@ kievite

I agree. I think that post-Soviet Russia was one of the single biggest tragedies of our time. That it was pursued in the name of ‘freedom’ was so disgraceful it barely bears thinking about.

I think that Naomi Klein got it wrong in one part of her story. Gorbachev was not a part of the solution, he was part of the problem. He was kind of mixture of Obama (blatant betrayal) with Bush (never mastered his native language; Gorbachevisms were the running joke in the USSR, much more so then Bushisms).

Despite the image of Gorbachev at Western media he was a weak deeply provincial politician who came to power as a result of compromise not due his real or perceive qualities. The key driver was the desire of certain members of Politburo to avoid electing Romanov — the first secretary of Leningrad (now Sanct-Petersburg) regional party office.

In a way Gorbachev is deeply Latin American figure: he simbolize sucessful attemt by the West to move Russia into the comprador model, in the strict Latin American sense, the state whose elite would be subservernt to America in foreign policy and would exist (and prosper) on exporting raw materials to the West and transfer money to the Western accounts, ordinary people be damned.

It was pretty symbolic that in the summer of 1994 when Gorbachev appeared a Russian Count to testify about his role in the aborted “putch” he was met by a gauntlet of protestors shouting, “Judas”.

Is it hopelessly naive to think that we can simply break up large banks (and the large companies with banking aspirations (GM, GE — I’m looking at you)) through a legislative process?

I think big banks should be broken up. And regulations should be put in place to prevent non-financials from engaging in excessive financial activity (which, by my measure, would be almost any).

I don’t understand why people around here think that I think otherwise. I’ve certainly never said otherwise. Personally, I think you have to pretty much denounce bankers in every post you do to get a good reaction from some people that read this site.

I think big banks should be broken up. PP

So theft of purchasing power is OK if practised in “moderation”?

But what if another country such as China decides to spur so-called “growth” by allowing its banks and borrowers to steal more purchasing power than the US? Wouldn’t that amount to a “counterfeiting gap”? Wouldn’t the US have to do the same to keep up?

IA: there is a difference between keeping the banks alive on government support, and leaving them to do their worst, by not punishing bankers for taking excessive risks. I do not know enough about the Japanese situation, but I suspect that Japanese bankers have been forced to behave within strictly defined parameters — at least when it comes to domestic lending and the like.

The reason I dislike Harrison’s argument is because he still thinks growth is a requirement for having a healthy economy. However, this all depends on what you define as healthy: corporate (profit) growth or mass employment and a low gini. I prefer the latter, whereas Ed seems to believe the former road must be taken. Therefore, I mostly agree with Philip’s assessment of Harrison’s argument there.

Hmpf. I must be an alien. If I had a bunch of excess cash laying around, why, I’d be rich (by any measure). I clearly and objectively would have more than I actually needed (a surplus) and would be perfectly happy for it to simply lay around. Sure, I’d use some of it to buy a few baubles for myself, but I would also be handing some to family members in the form of gifts or, if necessary, a load (with no big pressure to pay back…a gifty-loan, if you will).

If I have excess money laying around, why the hell do I need to generate even more by investing it in something with a high return? MUST I be a greedy f*cking piece of crap? MUST I be a pillager? A destroyer? A despoiler? MUST I be scum? Why isn’t enough simply OK to be, you know, enough?

Just some thoughts from the non-greedy, non-money-grubbing side of the H. sapiens family tree.

Just some thoughts from the non-greedy, non-money-grubbing side of the H. sapiens family tree. Praedor

You should read the Old Testament; it forbids usury from fellow countrymen and warns about profit taking (but not profit making) too.

You most certainly must not. However, the twin forces of inflation and (in some countries) a wealth tax to some degree encourage such behavior, as people have a horrendously difficult time accepting that their possessions can depreciate in value — or ‘rot’, if you will. Because whereas in pre-monetary societies could only have as much savings as the weather and their storage facilities would let them save, the money system (and stable commodities like gold) allows you to, in principle, keep your savings forever.

Some good ideas here, but I’m afraid you don’t understand the American political system. Politicians won’t vote for lower taxes only for low-earners (which in fact is the best way to stimulate demand), because they are bought off by corporations, esp the financial sector. Nor will politicians support government-created job programs for the unemployed. Stiglitz, Krugman et al have argued for New Deal style jobs programs and they are completely ignored. Politicians only support tax breaks for corporations and infrastructure things like high-speed rail, which are the most ineffective ways to create employment and/or stimulate demand. Actually, nobody in the political class really cares about poor and/or unemployed people, because they don’t vote. And in fact they like to have high unemployment, because it drives down wages.

Systemic change is next to impossible because American society is so fragmented and self-centered (some might say narcissistic). Americans don’t care about a problem unless it directly affects them. So, for instance, unemployment is not a problem unless it affects you, and that is only 20% of the population. Unpayable housing debt only affects 30-40 million at most – the rest of the country doesn’t care much. Health care prices don’t excite the public too much, because most people get health care as part of their jobs. Rising gasoline prices, on the other hand, that’s something that worries most people. And Social Security and Medicare too, because most people get it now or will get it in the future.

Hi Philip,

What does it tell us that you are sucked down the Irish black hole, but spend time trying to get the US out of its own black hole?

I would just like to repeat what Andrew Kaplan wrote nearly two years ago here on NC: the savings rate of households has not recovered at all (unless you ignore 99% of the population).(http://www.nakedcapitalism.com/2009/08/guest-post-the-savings-rate-has-recoveredif-you-ignore-the-bottom-99.html)

Good luck to all.

I did a post on Ireland last time I wrote something for here.

The savings-rate argument I’m making indicates that people are sucking aggregate demand out of the economy. I think the post you cite basically agrees with the low-aggregate demand argument.

This is perfectly in keeping with Richard Koo’s idea that the Japanese have experienced what he calls a ‘balance sheet recession’ – that is, a recession that is caused by companies retaining their earnings in order to pay down debt. This leads to a drain on reinvestment. Philip Pilkington

What if corporations did not have the government backed counterfeiting cartel, the banking system, to borrow from? What could they do to finance themselves? They could:

1) Use their own savings.

2) Borrow other people’s savings at honest interest rates which would typically be much higher than the counterfeiting cartel can offer.

3) Issue more common stock.

Neither 1) nor 3) requires debt and 2) would discourage debt.

So is debt needed for investment? No, it isn’t. Then why do corporations get into debt? Because they have to. If they don’t borrow from the counterfeiting cartel then the risk is that their competition will and leave them behind.

Solution?

1) Abolish government backing for banking.

2) Bailout the entire population equally, including savers, with new, debt-free fiat.

The government has no need for so-called “credit” since it has the right to create money itself and the private sector should not have it. So who needs banks? Ans: Nobody.

What has not been quantified on anyone’s charts is: the investor confidence factor!

Just as Japanese government chose to save its banking system over its citizens, US government is following this exact example.

Definition of stupidity, is repeating the same action and expecting a different result.

Japan, at bubble burst had surplus, US-DEFICIT!!!

Homeownership rates in Japan at bubble burst, were some of the lowest… US-THE HIGHEST!!!

Japan in 1990 barely had any consumer debt, it is mostly a cash society, US-ABOUT $40K PER PERSON!!!

US will not become like Japan… US will be so much worse, its unimaginable!

I welcome all comments at: providencegroup@ymail.com

The US is not Japan.

(sorry – couldn’t resist it)

So, it’s clear that the US citizenry need more bucks; but where should they get them? Why, from the government of course. After all, they’re the only realistic source right now. PP

So far, so good.

They can do this either through tax-breaks – for the working man, NOT for the rich PP

Also good.

– or some sort of employment program (I favour the latter, but I recognise that the former is probably more politically realistic). PP

What about a bailout of the entire population, including savers, with new, debt-free fiat? That would be the just thing to do. Why should people have work their way out of debt to counterfeiters?

Mr P, let me preface this with I am not being sarcastic towards you or your line of argumentation. Although you, erm need to go easy on the Japanese toilet fetish, it’s erm, eh a cultural thing, similar to the need for the Royal Wedding in Brit culture, although you do seem partial to the Stones, dude, that was a compliment. Enough pleasantries onto the analysis.

Yes, I need more pay in my check. The 1990’s saw the rise to what I used to refer to as the food stamps of the middle class, credit card debt. But, Obama has beat you to the punch on one issue, taxes. At least for the approx 1/2 of the nation that makes less than the mean income of approx $50k, we already are enjoying a tax holiday. Our tax refunds were a pleasure to behold. Of course, a job would be an even greater pleasure. And that seems to be part of the US is like Japan scenario. Capital is on strike, piling up to over $2Trillion and waiting for certainty on the sidelines, like they are waiting for Godot. In the mean time, those retaining employment are waged suppressed, overworked and politically oppressed by the baby murdering defense league of god’s vengeance and bible study college. Mr P, you have apparently missed a very strong contingent of anti fornication, anti masturbation and anti sex messaging leagues, councils and mothers against adolescent behavior. It is no wonder that many readers here at NC are fed up with the republicrats. The level of political sophistication has apparently caught up with Presidential 3rd party candidate from 1968, George Wallace. He could not find a dimes worth of difference between the parties. This of course led to the Southern Strategy which finally broke up the New Deal coalition along class lines. Apparently, not much has changed, wages are being suppressed and people are being emotionally depressed to suppress the urge to vote. Or at least find a 3rd party that will bring about as much change as Obama has. Think about it.

Mr Tioxon;

“Or find a 3rd party that will bring about as much change as Obama has.” As the Tech savy say; LOL! Talk about setting the bar too low. (Limbo economy anyone?)

On another note; how about rebranding the Roosevelt Institute to “promote and express the fearless reforming spirit of President Theodore Roosevelt!” Then the revived Bull Moose Party could be seen as a sort of Greens phenomenon.

Another immensely deflationary factor that is tossed about in the media but not fully appreciated is the education indebtedness of Gen. X Y Z et al.

Hey baby boomers, wanna unload your McMansion? All of you won’t be able to because collectively my generation already owes with a mortgage worth of debt to fund our education. So less money left over for everything else.

I should know, I’m one of them, lol.

Sincerely, I earn six figures :) but I owe six figures in edu debt :(

And the solution to the Great Financial Crisis ailing the US is…drumroll, please…

“The US citizenry need more bucks”, by Philip Pilkington.

And the government will accomplish this through…get ready, here it comes…The government will accomplish this through… An Employment Program!?

Yes! And the solution for cancer patients is…”They need to get more healthy.” And how will this happen? Through a Wellness Program, of course.

Problems Solved.

C’mon, man.

What are you talking about?

I’m not advocating a ‘wellness program’ — I’m advocating either tax-cuts or an employment program funded by the federal government — similar to the WPA during the Great Depression.

This would require running larger government deficits.

Cancer patient gets chemo — depressed economy gets fiscal stimulus. No wellness programs here.

Dan is a bitter old troll. Ignore him and he’ll go away.

Philip, are you kidding me? I really have to explain this to you?

I know you’re not “advocating a wellness program”. I was being sarcastic.

You make the statement—“[the solution] is that the US citizenry needs more bucks”…and it’s about as stupid (and effective) as simply prescribing good health to a cancer patient.

Sorry I ever made fun of you, Dan. Anyone taking a shot at this Pilkington jerk can’t be all bad. The enemy of my enemy is my friend.

Just like Japan, the US had both a real estate bubble and a stock market bubble. The S&P 500 had a lot of companies that were flying high because of the real estate bubble. The two bubbles were highly correlated, as my investment advisor pointed out at the time, which prompted me to get out of the stock market at it’s peak.

Do you ever have anybody review your stuff before you publish? You seem stuck in your own head, and a second set of eyes would help to purge the confirmation bias that permeates your work and make you look less like a hack advocate. I don’t mind if you continue down the path of being an advocate, but at least raise your game beyond hack status. You lose all credibility when you claim that there are facts that don’t exist. In this case, there was no reason to even make the bubble v. bubbles distinction you flubbed.

The stock market lost most of its value when the dot-com bubble crashed out. That was the real era of the US stock bubble. As Dean Baker points out in his book, this fall in stock prices was quickly counteracted by the rise of the housing bubble. The economy, in a sense, ‘switched bubbles’.

In Japan the major stock bubble and the housing bubble directly overlapped — so it was a different dynamic.

Look at the first chart I give (the one from Koo’s book). Note that share losses continued for over a decade. This didn’t happen in the US, as the stock market basically stabalised after the housing crash (due in part to QE?).

Will the stock market continue to remain stable? Actually I emailed Yves about this shortly after submitting the article. I think there’s an argument to be made that it’s stability is an illusion.

But back to the main point. Japan had their major stock bubble and crash correlated with the housing bubble. The US definitely did not.

We had an internet stock bubble, followed by a housing stock bubble. A lot of the damage caused by the collapse of the housing stock bubble was masked by swapping out the components of the S&P 500 and Dow Jones 30 to purge them of the most housing-centric stocks, which took major hits and have never recovered (assuming they’re still around).

Okay. But the fact still remains: the US’s major stock bubble deflated nearly a decade before the US’s housing bubble. The

Japanese major stock bubble directly overlapped with the housing bubble.

What’s that saying: you’re entitled to your own opinions, but you’re not entitled to your own facts. Get your facts right before you start trying to trash my articles.

“Get your facts right before you start trying to trash my articles.”

Please keep it civil even if the other party doesn’t. While TJ was obviously not trying to quality for an etiquette award himself, it is hardly helpful to the atmosphere here if you respond in kind. He makes substantive claims, so refute those and leave it at that.

What are you? A moderator?

If people are going to start talking smack and calling me a ‘hack’ I’m hardly going to invite them over for dinner and wash their feet. If you want a polite response, don’t call me names.

I’ve been told that this is where I should come for the abuse clinic. Ask for a Mr. Pilkingon.

Is this the right place? And in order to be insulted, do I need to get in line, or just stand here with a stupid look on my face?

The fundamental problem is this: Our leaders do not understand the differences between Monetary Sovereignty and monetary non-sovereignty. So they are conflicted between curing the recession (which requires massive deficit spending) and curing the deficit.

Sadly, “curing” the deficit serves no purpose whatsoever, and in fact, is counterproductive. A growing economy requires a growing supply of money, and the unfortunately-named “deficit” merely is the federal government’s method for adding money to the economy. Rather than calling it a federal “deficit,” it more correctly should be called an economic surplus.

That one little semantic change would help us get back to prosperity.

Rodger Malcolm Mitchell

I agree that the word “deficit” needs to be replaced because it implies that a balanced budget or surplus is good when they are not.

Thanks for the interesting article! Just some stray impressions based on my having lived in Japan during the 90s. First, I think you’re right about the community or communal ethic in Japanese society playing a role in employment practices. In addition to the feudal hierarchical ethic that still remains in effect to a certain extent, there is also a strong horizontal everyone-is-equal ethic (coming from former intra-village social relations?) which is equally strong. I think you could see it in action in the shelters where homeless people gathered after the recent great earthquake. The active cooperation and cheerful work-sharing were remarkable to me as an American. Though this sense of community and sharing with others is breaking down slowly, especially in urban areas, there is still a strong work ethic in Japan. Work is still generally thought to be the source of value, and financial speculation is not quite as glamorous as in the US.

At least partly because of these value-orientations, companies generally prefer to cut down on working time for workers rather than fire them, though many people were fired, especially in small companies; and as in Germany the government helps by reimbursing companies to a certain extent for keeping workers partially employed. Also, public workers are more respected in Japan than in the US, as are teachers, so there were no mass layoffs in these areas. Another reason for the resiliance of aggregate demand was that the generation which grew up during the war and suffered great hardships began to retire during the late 80s and 90s. They grew up and lived very thrifty, savings-oriented lives, and after retirement they wanted to share at last in the consumption-oriented society that grew up in postwar Japan. There was a lot of consumption of imported high-fashion and luxury goods going on then that would have been unthinkable during the time the postwar austerity ethic was dominant. And among older farmers, who had suffered a lot and had saved earlier in their lives, a threshold was apparently reached, and in the late 80s and the 90s it was common for older farmers to drive a Mercedes Benz.

I doubt that the toilet in the ad you put up was bought by many young people. I may be wrong, but I would guess that the ad was probably aimed at older people. Remember, Japan (except for northern areas) doesn’t have central heating (which saves a lot of energy…), so it’s quite cold when you go to the can in winter. Apparently a lot of strokes and other medical “events” take place there, so toilets with heated seats became quite popular with older people for health reasons. I believe they still are. I think you need to research that point better. It wasn’t only young people who continued to consume during the recession, and there was also the matter of timing: during the recession there was an unconnected and parallel basic surge toward cash consumption, though not so much toward credit cards.

One other possible reason for the lower saving rate in Japan. As you know, Japan has an excellent national health insurance system which almost everyone belongs to. Though the conservatives have chipped away at it, it’s still pretty good and makes the US look like a third-world nation in terms of healthcare insurance and healthcare cost control. That means Japanese don’t need to be nearly as worried about going bankrupt because of a serious illness or operation, so saving for a medical emergency probably isn’t as strong a motive in Japan as in the US. National health insurance may well make Japanese more optimistic about many aspects of life and perhaps makes them more confident about spending some of their savings during a recession, but you’d better research that point, since it’s just an impression.

Yes, I think the political-economic elite in the US is even crazier than the elite in Japan. A human-made tragedy is playing out in the US now that uses ideological terms most Japanese, I’m pretty sure, would find downright weird.

Regards

What he should be highlighting is that, more often than not, fastened to the end of the financial sector’s debt-chain is a low to medium-income human being. And that is where most of these debts ultimately land. That, in turn, is why this is, when we strip away the complexities, a fairly straightforward crisis of aggregate demand.

Hmmm… is this true?

Yes, a lot of the debt is eventually “held” by the average joe.

But an AWFUL lot of that debt is also held in the corporate sector as well. Last I checked, there is a huge overhang of debt from the LBO market and Commercial RE as well. Not to mention the debt from the derivatives market. Or are we pretending that is held by the average joe because the govt is backstopping it.

I would like to see data on how much debt is held by the common guy and how much debt is held based on LBOs and CDS and margin and leverage etc.

I think that a lot of the debt was tied to mortgages that went bad. These mortgages were probably held by average Joes.

Think about it: the US’s main problem is a housing bubble that crashed — people lose sight of this all too often, but this was the key problem. Now who buys houses? Certainly not financial institutions — they lend the money for houses to people, but do not buy them.

Follow a debt-chain in the US for long enough and I think you’ll usually find some small time chap at the end of it. In Japan, this was not so much the case as the corporate sector seemed to load up on debt directly.

I think that a lot of the debt was tied to mortgages that went bad. These mortgages were probably held by average Joes.

I really do not mean this as an insult (I’m very impressed that you are replying to us and appreciate it), but I believe you are seeing things in the same myopic way that the Fed/Bankers saw things back in the early phase of the downturn.

I’m guessing that we simply see things differently here…

to me, there is a HUGE difference between debt being TIED to a mortgage, and who HOLDS the debt.

using mortgage data:

I agree with you that the average American owes/owed a lot of mortgage debt.

HOWEVER: that was not the big problem with the downturn.

The big problem was all the debt TIED to that mortgage.

There were MBS and CDOs and CDS and CDS squared all TIED to the mortgage. This debt was not held by the average American, it was held by banks and other institutions, and this debt DWARFED the actual underlying mortgage market.

therefore: average joe held a lot of debt

Banks and Institutions owed A LOT MORE debt that they used to lever up and derivaterize (made up word!) Joe’s debt.

“this is only subprime” and “it is contained” were believed because people only looked at the nominal amount of aggregate housing debt, and ignored the leverage upon leverage allowed through the shadow and traditional banking sectors that was tied to (but significantly amplified from) that original mortgage debt.

===

in the end, your and my perspectives may boil down to the same prescription

regardless if you look at this as the Average Joe having the debt (as you do), or as the Financial institutions having the debt (as I do) the prescription is to get money into the hands of Joe.

he can thus pay his mortgage and the layer upon layer of debt can be “serviced”.

however; I think my point is important because your point ignores the layer upon layer of leverage, that requires NOT ONLY Joe to pay off his debt, but it requires many other Joes to go into new debt to feed the Ponzi.

This is why we saw the bankers abandon all sense and extend credit to EVERYBODY, and then we saw wobblings of the credit market BEFORE defaults even got going in the mortgage market… it is NOT enough to make debt and pay off… for our system to “work” we must create ever larger amounts of debt at an accelerated rate.

hope this makes sense, if not my apologies.

again, thank you for responding to us.

“therefore: average joe held a lot of debt

Banks and Institutions owed A LOT MORE debt that they used to lever up and derivaterize (made up word!) Joe’s debt.”

Oh, you’re absolutely right. However, Joe’s debt would have been impossible without the derivitisation — and the derivitisation wouldn’t have been necessary without financial corporations lending subprime and the like.

Ultimately, then, it is Joe’s debt that is at the root of the problem.

In this sense I think it is important to say that Joe really is the ‘holder’ of the debt — at the bottom of the chain, if you like. All the other debt depends on Joe’s defaulting or paying back the debt. If the debt is paid back there is no problem. But of course, the problem with this derivitised debt is that, by its very nature, it’ll never be paid back.

“it is NOT enough to make debt and pay off… for our system to “work” we must create ever larger amounts of debt at an accelerated rate.”

That’s only true if the private sector is forced to go into debt. If the government were to consistently run substantial deficits the system would not need dodgy private sector debt-layering. That was the theme of the article I ran on here a while back.

http://bit.ly/ihLV3s

“Ultimately, then, it is Joe’s debt that is at the root of the problem.”

No, ultimately it is the bonaz seeking behavior that drove the market for bad loans in order to have an excuse to build that alphabet soup ponzi scheme that is the root of the problem.

Unless “Joe” works at Goldman Sachs. In which case, how many times over does “Joe” have to pay off his student loan and mortgage before “Joe” has enough is satisfied with the annual salary of your typical mortal being?

I think that’s oversimplifying things quite a bit. Ireland currently has a loan crisis and Goldman Sachs are nowhere to be seen. Plenty of people holding unaffordable mortgages though. Hmmm…

Philip, I’m curious as to your thoughts on how to incentivise individuals against bubbles. Granted, irrationality of the “dumb money” late investors has been around forever, but are their ways to mitigate it?

My thoughts are that the housing bubble caused more devastation than the .com bubble because wealth loss this time around is more widespread and among individuals who could less afford to lose a big chunk of their wealth. Thus the great drop in aggregate demand this time around. There are also externalities associated with one’s residence tying one to a community and the illiquidity of selling and moving.

Certain individuals, Monevator quite presciently, and my family in part by luck, avoided buying into the market during the height of the boom because they saw it as overvalued. Many others it seems piled into the market at a greater frenzy in its final exponential phase. Is there a way of infusing that caution in the broader market either by policy or by incentives or am I too optimistic in thinking that everyone can learn valuations at a good enough level to avoid such mistakes in the future?

“I’m curious as to your thoughts on how to incentivise individuals against bubbles.”

First of all, stop necessitating private debt. This is done by running larger government deficits and increasing real wages.

Secondly, regulate the shit out of these institutions. Make sure they don’t allow a loan that is dodgy. Do this, as Yves has pointed out, by forcing them to put down some of their own cash as collateral.

The first is more important though. We need to tackle the demand for these loans. Make sure people have enough money and that they don’t need debt. That’s 80% of the battle.

“My thoughts are that the housing bubble caused more devastation than the .com bubble because wealth loss this time around is more widespread and among individuals who could less afford to lose a big chunk of their wealth.”

Absolutely right. This was a bubble inflated on the common citizen. Financiers were essentially gambling on people’s livelihoods. It’s disgusting.

“Thus the great drop in aggregate demand this time around.”

Yep. I think so.

“Is there a way of infusing that caution in the broader market either by policy or by incentives or am I too optimistic in thinking that everyone can learn valuations at a good enough level to avoid such mistakes in the future?”

No, I don’t think there’s a way of ‘regulating’ people’s aspirations.

Think of this as gambling. Why do people gamble? Generally because they aren’t happy with their lot and want to improve it. So, the key is to make sure people are happier with their lot. This needs to be done through increases in real wages and a reduction in household debt.

To drive this point home because, conflicting as it does with market-mythology, I fear it will be lost on many: Corporations with mass capital outlays aren’t formed by heroic entrepreneur-types overnight. They are highly evolved social institutions that take much time and collective effort to build. If these are destroyed you would likely end up with a sort of ‘cowboy capitalism’ filling the void; a system geared toward short-term profit – perhaps even criminality – rather than long-term growth and stability.

Ahh… but it’s a catch 22 isn’t it?

the longer we prop up zombie banks (and corporations) with Governmental guarantees and subsidies the more uncompetitive our market becomes squeezing out new players.

thus: if we don’t bail out: cowboy capitalism (I like that phrase).

if we do bail out: starving new entrepreneurs and allowing TBTF to get worse. (which is what was done… look at the monster that as become of BofA, Wells, Goldman, et al).

there is a third option you don’t mention however… it’s a dirty little word. Nationalization. Sorry… “pre privatisation”.

we need to nationalize to kill the zombie banks. then we can slowly open up the market again to allow new entrepreneurs to take their place without the Shock Doctrine that Naomi so eloquently discussed in her book.

It’s only a catch-22 if you look at it in the terms you look at it in.

Government bailouts don’t have to lead to inefficient structures. I don’t see much evidence that the Japanese corporations that were bailed-out became lumbering Soviet-style inefficiency engines.

People need to drop the ‘market = efficiency’ mythologies — it’s just not true. Government funded institutions can be just as efficient. The military in the US, for example, develops stunning technology that is then used by the private sector (the internet is just one example).

This is a very interesting topic that I only touched on in the above article. I’d recommend JK Galbraith’s ‘New Industrial State’ if you want to pursue it further. Some of it is a little dated, but I think his description of how the ‘technostructure’ works in a modern economy is spot on. Hint: it has almost nothing to do with ‘markets’.

He summarised his argument in one of the episodes of a TV series he made in the 1970s called ‘The Age of Uncertainty’. You can watch the episode here:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Aq5UmgdI57I

It’s only a catch-22 if you look at it in the terms you look at it in.

perhaps, but I think I”m looking at the issue correctly.

more below.

People need to drop the ‘market = efficiency’ mythologies — it’s just not true. Government funded institutions can be just as efficient.

I agree. That’s why in my response I specifically said we need to NATIONALIZE the financial sector, and then sell it off later.

as I see it we have 3 choices

1) remove TBTF support/guarantees and then deal with the consequences. There is no question that a huge number of them are insolvent (not illiquid). thus this could very well result in “cowboy” capitalism or perhaps the “utopians” have it right and we’d see rebirth of new companies (I actually agree with you, we’d see cowboy capitalism).

2) continue the TBTF support/guarantees as you seem to be advocating. We have 2-3 years of experience with this. The results are clear. The big guys are starving out any hope for new entrants. The TBTF problem has WORSENED. The major problem is that we are wasting our money. The TBTFers are simply using the money to pay bonuses, fill acute holes in their balance sheet, or to gamble with in their proprietary trading regimen (since they have a GOVERNMENT guarantee).

Research on HORDES of downturns has shown this to be the case, and we CLEARLY see it currently.

or

3) nationalize. politically difficult in these times but should have been done before and should still be done. Obama’s biggest failure.

if you nationalize then you take CONTROL of the banks and you can open up lending (IF you believe it is worthwhile) and you can stave off cowboy capitalism until the financial sector is trimmed and “healthier”

How am I looking at this wrong?

are you arguing that we are doing our economy GOOD by propping up BofA, Wells, JPMorgan, Citi, et al?

what more support can we possibly give them?

I’m not talking about banks, I’m talking about non-financial corporations in Japan.

You are as slippery as an eel. Either you are a satirist or you have never heard of the “Zombie Banks” in Japan, which our own criminal “cowboy capitalists” like Summers and Rubin

urged them to shut down. “JOE” had nothing to do with the creation of 600 trillion in off-exchange derivatives. The counterparties are the interlocking banks. Many of us here are ready to weather the New Great Depression, (which began in about 1999, mooting your “housing vs stock bubble” timing issue)as long as some of those “highly evolved” systemically critical criminal syndicates are torn down.

What you do not see is that we are going to have a massive Crash and Greater Depression no matter what we do. So, the real question is: do you wish to see justice or do you sell out?

““JOE” had nothing to do with the creation of 600 trillion in off-exchange derivatives.”

Yeah, actually, he did. And until you come to grips with that, you won’t come to grips with much.

stockdude is right. “Kill The Squid” is the only commonsense attitude since it will continue to blow its venomous bubbles in real estate, commodities, government debt, etc. Simply providing economic stimulus to low income citizens will not remove the ever present danger of The Squid continuing to blow up and burst bubbles i.e. generate economic instability. Since neither market or government provides much restraint on The Squid manufacturing money to blow bubbles (bubble losses are socialized to the tax payer)it is time to cut the public charter umbilical cord feeding the capacity of The Squid to manufacture its money. The capacity should be placed in the hands of a democratically elected trust representing the sectors of the real economy including the unemployed and avoiding as far as possible the clutches of politicians and bankers.

Just a link to this trash with some commentary describing it as such would have sufficed. Hope this blog hasn’t gone over to the dark side. We get enough of this worthless crap in mainstream media. We come here for the truth. Don’t let us down.

I agree. Or just a link without commentary would have sufficed.

Philip’s reply to me just above re: 600 trillion in derivatives shows he wasted too much NC time. I’m done with him.

By the time this Pilkington Blietzkrieg is over, the only ones left standing at NC will be the Wall Street types.

Pat you are right that hardly anybody cares right now in the US but shrinking aggregate demand will change that situation at some point. But old adages immediately spring to mind like a stitch in time…..etc. or Churchill’s that you can always rely on Americans to eventually do the right thing.

The Vapors – Turning Japanese

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gEmJ-VWPDM4

Hehe… comparing the US and Japan? This song comes to mind:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Mui4CM2SKWM

Rodger Malcolm Mitchell is so right. If you regard one of the main qualities of money as commanding resources then money is a “command catalyst” and if the private sector won’t invest because its either too scared or too busy paying down debt then its government you have to turn to to deploy some “command catalyst” to revive your economy after The Squid has tried to demolish it. Government afterall is a creator of money who owes nobody anything for doing it other than endeavoring to maintain the real value of that money.

Despite liking the article I take issue with this section:

[i]These are the entities that have incurred huge debt-loads and find it difficult to function while Japanese consumers have inadequate resources to purchase their wares. If the Japanese were to ‘smash the technostructure’ – which would be politically impossible anyway – the result would probably be mass unemployment and a serious economic depression.

To drive this point home because, conflicting as it does with market-mythology, I fear it will be lost on many: Corporations with mass capital outlays aren’t formed by heroic entrepreneur-types overnight. They are highly evolved social institutions that take much time and collective effort to build.[/i]

You describe what would happen in absence of a sound bankruptcy regime. Generally if a company fails the functioning parts are kept as intact as possible and continue running under new ownership, see Jaguar, Land Rover and the Mini, whilst the non-functioning bits are shut down, see Rover itself.

Generally if a company could turn a profit without their current debt load then someone will acquire these parts during bankruptcy proceedings. Bondholders lose their shirts but that is a risk they chose to take.

The issue you outline above is only a serious concern when the company in question has no competitors or if all companies in a sector fail at the same time. If an entire sector fails due to a shock then I can fully understand why short term support might be neccesary, if there are chronic issues then you’re generally better off letting the weakest companies fail.

I think having a single company file for bankruptcy due to low-profitability — as in the case of, say, Rover — and having an entire corporate sector leveraged up to the eyes due to a speculative bubble are different things.

Perhaps there’s a few moochers in the Japanese corporate sector that are using the government to support entirely unprofitable companies. But my understanding is that most are in fact profitable, but have serious balance-sheet problems due to the crash.

Also, take into account the fact that many companies might be unprofitable due to low aggregate demand and deflation. If these are allowed to fail it would push unemployment up which would further exacerbate the aggregate demand problem — this in turn will hurt more companies that would then fail and so on ad infinitum.

That seems to me like a recipe for a depression.

If the issue is with aggregate demand I would still argue that something putting cash directly into the hands of consumers, like a tax rebate, is preferable to subsidising a failing industry.

If the company is unprofitable it leads to a wasteful use of resources, supplying it with raw materials, ebergy etc costs money and has an environmental impact. If it produces things which people ultimately don’t want to buy a large part of these inputs are wasted.

In addition a large slice of these subsidies will be going towards servicing the existing onerous debt rather than feeding aggregate demand.

A tax-cut won’t do much for an unemployed person.

My preference is that the government do both. If it let the companies fail any fiscal policy it focused on raising aggregate demand would be eclipsed by rising unemployment.

The alternative is to let the companies fail and initiate a government works program. Because of certain conditions in Japan, I don’t think this is applicable. I think the people are better off employed servicing each other in low-profitability businesses than they are building roads that they don’t need.

If Japan were as underdeveloped in their public provisions as, say, the US, I would have a different view altogether. But my impression is that it isn’t.

I broadly agree, however in that case an orderly bankruptcy in which the debts are discharged and the owners/bondholders take their losses are probably still preferable.

I used Rover but I could be talking about Greece, or US Homeowners. Ultimately the scenario is that for various reasons it is impossible that they will repay their debts in full or that certain investments will match the returns they achieved in the boom years. At some point this has to be recognised and accounted for.

If there is a profitable business there it will ultimately not vanish.

But what about my second point — which is really the key one?

If a business is struggling due to low aggregate demand, closing the doors will only lead to higher unemployment and even lower aggregate demand. This, in turn, will lead to more companies experiencing difficulties and so on.

Bill Mitchell points out that a lot of people complain about the ‘stagnant’ service sector in Japan — and yet, anyone who goes there is surprised by how pleasant it is. Mitchell points out that the service sector is only ‘stagnant’ from the point-of-view of profitability — from the point-of-view of employment and service it’s absolutely top notch.

“Mitchell points out that the service sector is only ‘stagnant’ from the point-of-view of profitability— from the point-of-view of employment and service it’s absolutely top notch.”

That certainly is a single minded focus. And yet you continue to insist that the root problem was Joe’s unpaid mortgage and not rent seeking and bonus seeking behavior. The truth is that you can pay down all of Joe’s millions of mortgages, get every single one of him an eight buck an hour job with the MMT-ers (and the necessary spot in public housing that goes with an $8/hr job), and the root problem driving global economic instability will remain.

“The truth is that you can pay down all of Joe’s millions of mortgages, get every single one of him an eight buck an hour job with the MMT-ers (and the necessary spot in public housing that goes with an $8/hr job), and the root problem driving global economic instability will remain.”

Considering that MMT grew out of Hyman Minsky’s work, I think that most of us are more than a little aware of the causes of financial instability…

No MMTer, I think, would eschew the need for serious financial sector reform — broadly, I think, along the lines laid down by Minsky — but that doesn’t discount the fact that financial instability is not the only economic reform needed.

I’m trying to address problems other than the rotten banking sector. I think Yves does a perfectly good job on the banking sector and I only hope to supplement that with pieces on macroeconomic reform. And for this everyone thinks I’m in bed with the bankers or, at least, consider the banking sector irrelevant. It’s absurd.

And for this everyone thinks I’m in bed with the bankers Philip Pilkington

Because you are. You think central banking is a necessity when it isn’t.

Forgot how much I adore him (JKG). So brave for his time (and ours). The shareholders are ossified. Buy them out and socialize the corporation and use it to promote the social good. I would just say do not socialize it temporarily and sell it back asap. That would not change the system. It is either socialize a sufficient part of the economy, or socialize the losses (or suffer massive unemployment). Wonder how fine a point Galbraith would put on the “banking” crisis. I’m sure he wouldn’t be mincing his words or holding fake press conferences. His “Board of Public Auditors,” “the Trend created Ralph Nader,” the CEOs always go on to become Secretary of War. I wish someone would keep his thinking front and center. Philip, your suggestion that we are vilifying corporations stopped me in my reactionary tracks. I just had an epiphany down memory lane. Thanks.

@ Susan

I absolutely agree. No other economist has influenced me as much as JK Galbraith. He had a wonderful vision and it saddens me that is largely forgotten today.

Everybody now just shut up and listen to Professor Phil.

He’ll straighten you miserable lot out.

Pupil Mahood, you’re not *listening*! Now, repeat after me, for the twenty-five thousandth time, what is MMT?

What is a vertical transaction? What is a horizontal transaction? What is (G-T) = (S-I) – NX

I *can’t* hear you!!

And while you suckers figure it all out, me and my friends will just keep on looting the f**k out of you until there isn’t a pot left to p*ss in, you pathetic retards.

For a moment there, you almost had me worried. For moment it looked like a gathering band of anti-bankster, anti-capitalists right here at NC, and I was getting a little nervous. My A-team (Alex and AJ) just wasn’t up to the job. But then, from out of nowhere, and working for free, along came Professor Phil and happy days are here again!

Can you say Bankster Paradise! It doesn’t get any better than this.

ha ha ha ha ha

Sayanora, Suckers!

Chow, you pathetic bunch of losers!

It’s been interesting to observe the contrast between the articles at NC and the comments. Compare that to places such as Marginal Revolution or Outside the Beltway, for example.

The ultimate difference, I think, is that the audience (I hope not the writers) here at NC is virulently anti anything that they think lets others make more money than themselves (regardless of work ethic or productivity).

Most people (including myself) elsewhere draw a distinction between wealth that they think is fairly earned (e.g. Gates, Buffett, Page/Brin, Woods, P. Manning, Lady Gaga) and wealth that is due to extraction of rent (e.g. financiers taking a cut of transactions, bankers getting easy money directly from gov’t printing presses, executives at unprofitable companies getting golden parachutes and generous stock options, union workers making multiples more than their counterparts in the private sector and definitely more than comparable workers overseas). The difference, I think, can be summed up as whether you contribute something that is truly irreplaceable in the market (be it athletic prowess, musical skill, or entrepreneurial excellence) as opposed to through corrupt bargains and gaming the system.

It seems that some/most people at NC do not hold even this distinction and want to punish the first group as well as the second. This is why, for example, I am more in favour of systemic reforms and stronger banking oversight/consumer protection versus simply adopting F. Beard’s idea of printing loads and giving it to everyone (evening out the playing field, so to speak) or writing off all private debt as illegitimate.

Yes, let us withdraw nakedcapitalisms petition to clawback Lady Gaga’s wages. You must not have read much commentary here.

This is why, for example, I am more in favour of systemic reforms and stronger banking oversight/consumer protection versus simply adopting F. Beard’s idea of printing loads and giving it to everyone (evening out the playing field, so to speak) or writing off all private debt as illegitimate. Richard

Actually, I call for fundamental reform too; much more fundamental than say Phil’s. I advocate that money creation be totally ethical with separate government and private money supplies per Matthew 22:16-22.

It’s always fascinating to contrast the views about central banking on NC versus on marketwatch. They’re both negative, but for totally different reasons. Marketwatch commentators believe that the Fed’s existence has helped debtors much more than creditors because of its bias towards inflationary levels of money creation.

I can’t say I’m a fan of relying on millenia-old texts to instruct modern society on morality or economic systems. There’s no way for me to debate that issue with you though, as our belief systems are different on that basis alone. You might call me a “godless capitalist”, heh.

Still, I’m intrigued as to alternate money creation mechanisms (perhaps a blind policy targeted at increasing money supply by a fixed % of GDP). Central banking has shown to be easy for political influences and corrupt bargains to be struck.

Still, I’m intrigued as to alternate money creation mechanisms (perhaps a blind policy targeted at increasing money supply by a fixed % of GDP). Richard

Why limit the amount of money government can create? Let government create all the money it wants to but with the proviso that only the government and its payees suffer any price inflation should the government overspend wrt taxation. The way to do that is to allow genuine private currencies for private debts.

Please explain in more detail. How would you constrain the inflation from affecting all individuals? How would you channel the newly created money? Would you distribute it to all individuals as a lump sum? Proportional to their amt. of tax paid? Would it go to finance gov’t deficit spending?

The existence of a private currency system and a public system won’t fly because economic entities won’t consent to being paid in one of those currencies.

Please explain in more detail. How would you constrain the inflation from affecting all individuals? Richard

Currently, government money is legal tender for private debts. That is absurd. Government money should only be legal tender for government debts in fact as well as law.

How would you channel the newly created money? Richard

Government would simply spend its money into existence and tax some of it back out of existence.

Would you distribute it to all individuals as a lump sum? Richard

No, not normally. But I do propose a one-time bailout of the entire population.

Proportional to their amt. of tax paid? Richard

No

Would it go to finance gov’t deficit spending? Richard

Yes.

The existence of a private currency system and a public system won’t fly because economic entities won’t consent to being paid in one of those currencies. Richard

People could always use the government’s money for all debts if they chose too. But the existence of private currency alternatives would tend to make government spend wisely since people could escape its currency if necessary.

Come on guys! The government doesn’t ‘create’ money. If the crisis has taught us anything it should be that.

Money is created by… the demand for money. There’s no constraints — no government constraints. Most governments have scrapped reserves because of this.

Money is demand driven. It’s as simple as.

Money is created by… the demand for money. PP

No Phil. One can demand money all he wants but unless a bank lends it or the Treasury spends it into circulation then there will be no new money.

Philip–the reason some people intuitively think you are in bed with the bankers is that during the past few years acutal U.S. citizen have not benefitted much from many types of fiscal transfer–while the aggregate balance sheet did benefit–along with AIG, Maiden Lane bond holders and agency debt holders.

We do not enjoy seeing the amazing power of the Federal Reserve and the Treasury being used to purchase risky debt and then overpay these same bondholders for their idiot decisions.

Eventually people will curtail the governament stablization role if the government is not seen as acting in their interests.

Is it the case that without structural reform MMT may be doomed?

And with structual reform MMT may be irrelevant?

“Is it the case that without structural reform MMT may be doomed?”

I don’t think so. If public sector debt really does ‘cancel out’ the need for private sector debt — and I think that this is true beyond a shadow of a doubt — even without structural reform, implemented MMT would help faze-out much of the private financial sector.

This is not to say that structural reform should not be undertaken, it should. But even if it wasn’t I think sustained deficits would help get rid of the need for private credit and hence for financial institutions.

“And with structual reform MMT may be irrelevant?”

Certainly not. Unemployment will outlast any structural financial sector reform. Also, trying to run public surpluses will force the private sector to figure out some way of going into debt. This, if I were to guess, would probably lead to new circumventions of the regulatory process.

The US citizen has benefited somewhat, though in hard to visualize ways. Yes, it was a mistake to allow non-financial firms to become as leveraged and speculative as financials. Yes, financial firms had far too low reserve requirements.

However, the time for complete restructuring of the system is after the crisis (as in now). During the depths of the crisis, with the situation as it was, it was bailout or a complete collapse of the banking system.

I would like to see you argue how a complete collapse of major banks (then spreading to most smaller regional banks through a web of entanglement) is beneficial to an average US citizen. Loans would surely be impossible to come by. Aggregate demand would fall even more through the floor.

It’s only because the benefits of fiscal transfer have been aimed at averting a worse disaster rather than improving upon the good times that public opinion is directed against good policy. It’s the ultimate dilemma for policy makers. If *bad situation* happens, you get blamed. If worst *bad situation* is avoided but times are somewhat bad, you still get blamed equally as hard because people never experienced the worst *bad situation* and don’t have the ability to comprehend what a hellhole they have just avoided.

It seems that no matter what happens, people will always be complainers. Even at the height of the boom years (1999), people were still complaining that wage increases were below their expectations (leading to now incredibly luxurious wages for e.g. unionized west coast longshoremen).

Just curious. Are you for or against the government intervention at GM, now that the results are visible?

Is that directed at me? If not then sorry for responding.

First off, reserve requirements don’t constrain lending. So, that’s a bit of a non-issue.

Secondly, yes, I think that GM probably should have been bailed out. But I think they should have been more stringent on the conditions. Perhaps they should have even extended more capital to GM with the provision that it had to be invested in green technology and the like.

With over-mature corporations like GM it is becoming increasingly clear that government needs to play a bigger role in their management decisions and their balance sheets.

The alternative is to let them die out. I really don’t think that would help anyone.

Perhaps they should have even extended more capital to GM with the provision that it had to be invested in green technology and the like. Philip Pilkington

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Definitions_of_fascism

Sorry, Philip. I wrote it directed at Jim but it posted after your post.