By Satyajit Das, the author of Extreme Money: The Masters of the Universe and the Cult of Risk (Forthcoming September 2011) and Traders, Guns & Money: Knowns and Unknowns in the Dazzling World of Derivatives – Revised Edition (2006 and 2010)

The proposal to extend the maturity of Greek bonds emanating from the Élysée Palace reflects French strengths first identified by Napoleon III: “We do not make reforms in France; we make revolution.” Structured to meet a German requirement that private creditors contribute to the Greek bailout, the proposal falls short of what is actually required.

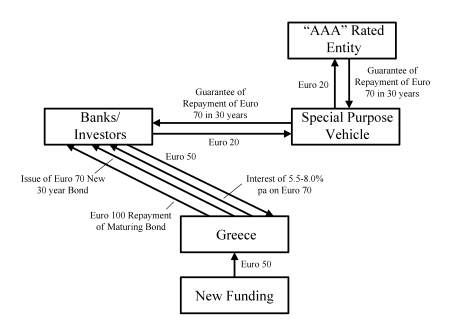

Under the sketchy proposal, for every Euro 100 of maturing bonds, the banks will subscribe to new 30 year securities, but only equal to Euro 70 (70%). Of the Euro 70, the banks, in turn, will only give Greece Euro 50 (50%) and invest the other Euro 20 (20%) in 30 year high quality zero coupon bonds (via a special purpose vehicle) to secure repayment of the new bonds. The new 30 year Greek debt will carry an interest rate of 5.5% per annum with a bonus element linked to Greek growth of up to an additional 2.5% per annum.

Of the Euro 340 billion in outstanding Greek bonds, banks hold 27%, institutional and retail investors hold 43% and the International Monetary Fund (“IMF”) and the European Central Bank (“ECB”) hold 30%. It is not clear whether non-bank investors are willing to participate in the arrangements. The ECB has previously resisted any debt restructuring, including maturity extension.

The French plan assumes holders of bonds would agree to roll over 50% of their holdings to provide Greece net funding of Euro 30 billion. But under the French banking federation’s own figures, this would if impossible unless all the Euro 60.5 billion (excluding central bank holdings) maturing by mid-2014 is rolled over. This is inconsistent with the proposal’s assumption of investor acceptance of 80%.

As not all Greek debt trades at the same price in the secondary market, if all bonds maturing are not rolled over, then banks could arbitrage the offer exchanging bonds trading at a deep discount, holding on to those trading at better prices.

The plan assumes that the “voluntary” exchange will not be treated as a “selective or restrictive” default by rating agencies or trigger credit insurance contracts on Greece. Fitch Ratings and S&P have indicated that the French plan will “very likely” be deemed a default, albetit for an unspecified “temporary” period, as it constitutes a distressed debt restructuring.

The Euro 20 invested in high quality collateral will need to earn around 4.26% per annum to accrete in value to Euro 70 to cover the principal of the new 30 year bonds. German 30 year bunds currently yield around 3.75% per annum, less than the required rate. Other AAA rated bonds, such as the European Financial Stability Fund (“EFSF”) bonds, might be used to provide the extra return. Given that the EFSF is backed by guarantees from countries with questionable long-term credit quality, the security afforded by such a guarantee is unproven.

Greece must find Euro 50 for every Euro 100 debt exchanged under the proposal. Given it has no access to commercial funding, this would have to come from the EU, IMF, EFSF or ECB.

Greece’s cost would be between 7.7% and 11.20% per annum, as it only receives Euro 50 of the Euro 70 face value of the new bonds. Assuming the remaining funding is at 6%, then Greece’s blended rate for every Euro 100 of finance would 6.85-8.60% per annum, compared to the 7-8% per annum considered sustainable by markets.

Most importantly, the overall level of debt, considered unsustainable, of Greece would remain unchanged.

The exchange scheme seems designed primarily to allow banks to avoid recognising losses on holdings of Greek bond. Even if the principal of the 30 year bonds is “risk free”, the interest on the bonds remains dependent on Greece’s ability to pay. Valued at a rate of 12 % per annum for 30 year Greek risk (a not unreasonable estimate), this would mean that the new bonds are only worth around 64% of face value, equivalent to a mark-to-market loss of around 36%. It is not clear if the authorities will require this loss to be recognised.

One alternative under consideration, an exchange of maturing bonds for new 5 year (French proposal) or 7 year (German) bonds is even worse as it defers the problem for an even shorter period of time.

A more logical solution would be that suggested reluctantly by the Institute of International Finance. Under this proposal, Greece would repurchase some its outstanding debt at current market prices, well below the face value of the bonds. This would reduce Greece’s debt level. It would also result in the bank’s sustaining losses.

According to the Bank for International Settlements, French banks have exposures to Greece, including of around Euros 50-60 billion. German banks have exposures of around Euro 30-35 billion. These banks might result require new capital to absorb the writedowns. If necessary, then the French and German governments would need to provide this capital. In effect, rather than lending to Greece, it would have to use the funds to recapitalise its own institutions. This would, in the final analysis, be more sensible than continuing with the farce that Greece is solvent and the bank’s holding of Greek debt are worth the face value of the securities. It would be the first logical step in addressing the problem of over indebted European nations.

History records that in August 2001, the IMF oversaw a debt exchange for Argentina in an unsuccessful, last ditch effort to avoid default. Indecisive and confused action by European authorities seems doomed to ensure that this restructuring, if it eventuates, will be followed by others and an eventual messy, disorderly and expensive default.

The French proposal perpetuates the lack of acknowledgment that Greece has a “solvency” rather than a “liquidity” problem. Like the EFSF whose structure has been criticised as nothing more than a collateralised debt obligation (“CDO”), it uses financial engineering techniques to defer or disguise losses in an unending game of “extend and pretend”.

How much is this bailout, through our funding of IMF, going to cost the US taxpayers? With all the talk of budget cuts and debt ceilings, how can we afford to bail out Europe?

My friend, I’m afraid you have been misinformed about the goals and purposes of organizations such as the IMF, World Bank, USAid, etc. The IMF was not established in order to “bail out” anybody. It’s only goal has always been to divert public funds (from the US and many other nations) toward the noble goals of looting, raping, and pillaging of other nations for the benefit of the elites in the developed nations (primarily the US and Western Europe). Such activities are sometimes double-spoken in terms such as “privatization”, “austerity”, “loans”, “development”, however the favorite term has been “aid”. Of course, the term “double speak” comes from George Orwell’s classic book 1984 and it refers to language that deliberately disguises, distorts, or reverses the true meaning of words.

For example, the IMF may offer Greece $20 billion in “aid” or “loans” with the understanding that in exchange Greece allows for the “privatization” of major real public assets (ports, airports, freeways, beaches, natural resources), where “privatization” basically means to allow foreign “investors” (i.e., crooked rich people from the US or Western Europe) to practically steal those assets. Such a deal may also demand that Greece grants major contracts to gangster US or European corporations such as Bechtel or Halliburton, typically for infrastructure projects that usually never get finished. As far as the initial $20 billion ‘aid”, it is either transferred into the bank accounts of corporate criminals such as the aforementioned Bechtel or Halliburton, or if any of it does arrive in Greece at all, it is promptly stolen by corrupt Greek elites and politicians and quickly disappears in their secret offshore personal bank accounts.

The same principles are at work when you hear on our corporate-controlled mass media about things like, the United States has given X number of billions of dollars in military aid to nations like Egypt, Pakistan, or Israel. Translated from double-speak into plain English, that simply means that the American taxpayer has paid for tanks, cluster bombs, and other nasty weapons to be shipped to those nations in order to be used to oppress peoples that would become destabilizing to US interests (a.k.a. US elite’s interests) should they become too free or, God forbid, seek democracy.

So, my friend, to summarize: first, the US taxpayer is ripped off when the US government contributes to the IMF. Second, that money is used to rip off taxpayers in other nations by robbing their nations of valuable assets. And, most amazingly, all this time uninformed and brainwashed American and Western European chumps (a.k.a. “taxpayers”) are convinced that they are “aiding” poor nations everywhere.

Quite a scam, huh?

Psychoanalystus

To add to my post above, I highly recommend these best seller books, which discuss this topic extensively:

“The Shock Doctrine” by Naomi Klein,

“Confessions of an Economic Hit Man” by John Perkins.

There are also many Naomi Klein speeches you can view on YouTube or on CSPAN’s Book TV.

thank you, satyajit das, for posting this clear, concise, edifying piece here at nc.

Thank you I’m such a sucker for good diagrams.

By the way no one forget that government debt of US and Greece are not remotely analogous. The US is a currency issuer and Greece is a currency user. Government debt of a currency issuer is the currency user’s savings as a matter of double entry accounting. It’s just a digital account corresponding to all currency users’ savings in banknotes, deposits, and treasuries. See DollarMonopoly.com Think of it as a friendly reminder so you economists stop all the destructive policies. Peace – I’m out

Molly Ivins: “It’s hard to convince people that you are killing them for their own good.

Hudson: “Socrates said that ignorance must be the root of all evil, because no one deliberately sets out to be bad. But the economic “medicine” of driving debtors into poverty and forcing the selloff of their public domain has become socially accepted wisdom taught in today’s business schools. One would think that after fifty years of austerity programs and privatization selloffs to pay bad debts, the world had learned enough about causes and consequences. The banking profession chooses deliberately to be ignorant.”

The exchange scheme seems designed primarily to allow banks to avoid recognising losses on holdings of Greek bond. Satyajit Das

It’s odd to me that a business would not wish to honestly know the value of its assets. Is that willfull blindness limited to banking? And if so, what is it about banks that make them different from other businesses? Is it not that by refusing to admit a loss that banks maintain their ability to keep creating and loaning money (credit)?

And why are banks forced to adhere to accounting standards in the first place aside from tax purposes? Shouldn’t it be the bank’s business what accounting standards it uses?

What a refreshingly naive perspective you have. My faith in human nature has been partially restored at least.

However I am sorry to say that the reasons banks don’t want to recognize accounting losses is because their managers would then have to admit to their failure to properly do their job for the last few decades and hence stop paying themselves generous salaries and bonuses. Governments would also have to use public money to recapitalize the institutions, admitting to firstly their regulatory failures and secondly they may also be forced to admit that they always put banker interests over public interest.

I love the complexity of the proposal — guaranteed never to be understood fully, nor followed entirely.

Simple alternative: Greece becomes Monetarily Sovereign. Problem solved.

Rodger Malcolm Mitchell

spooz,

IMF and World Bank loans are usually made only if the recipient agrees to accept and implement a structural adjustment program, the main elements of which are [and here I’ll borrow from Waldon Bello]:

– Removing restrictions on foreign investments in local industry, banks and other financial services. No longer could local industry or banks be favored or protected against giant foreign intervention.

– Reorienting the economy towards exports so as to earn the foreign exchange required for servicing the debt and so as to become correspondingly more dependent on the global economy. The effect was to reduce self-sufficiency and diverse local production, in favour of single product manufacture or agriculture, for example, coffee.

– Reducing wages or cutting down on wage increases to make exports more “competitive” and radically reducing government spending including spending on health, education and welfare. This would control inflation and assure that all available money be channelled into increasing production for export. But the few social services that remained were gutted.

– Cutting tariffs, quotas and other restrictions on imports, to grease the way for global integration.

– Devaluing the local currency against hard currencies like the dollar in order to make exports still more competitive.

– Privatising state enterprises, thereby providing further access for foreign capital.

– Undertaking a program of deregulation so as to free corporations that were involved in the export business from government controls that protect labor, the environment and natural resources, thereby cutting costs and further increasing export competitivity. This also had the secondary effect of forcing down wages and standards in other countries – including industrialized countries – to maintain their competitiveness.

This package may have benefitted transnational firms and a comprador elite within the host countries but in general made them poorer and locked into a borrowing cycle. Not for nothing did most in Latin America come to blame the IMF

for ‘the lost decade’ of the 1980s, weak growth during the 90’s, and side by side increased poverty and debt sucking up export earnings.

Psychoanalystus is right to recommend Naomi Klein but Joe Stiglitz [World Bank Chief Economist, 1997-2000] woke up and has written some strong critiques, or you might find some of U Mass [Amherst]econ professor James Crotty’s work worthwhile. Here is one of his from 2000 – Structural Contradictions of the Global Neoliberal Regime – http://people.umass.edu/crotty/assa-final-jan00.pdf

Let me note that ‘neoliberal’ corresponds with the IMF/WB programs though usually refers to the ideology.

I will finish by stating that neoliberalism has killed millions of people….it has been very far from neutral.

Nice article — thanks.

Personally, I’m not convinced that neoliberalism has much of rational theoretical support except the idea to “steal all you can while you can because you can”.

I see these new bonds as rather attractive, with security of principal plus a potential kicker if there is an inflationary boom. Do watch the early repayment clauses, though!

I think that the right analogy is the GSEs of the US. Every prospectus apparently said in red letter “This is NOT guaranteed by the US Treasury. Similarly in Europe, we are told that are NO cross-guarantees between government issues. But what we have here is the Community (if I’ve understood correctly) stumping up 50% of the maturing amounts and offering a darn good deal for the institutions to say they have rolled over 70%. That 70% breaks down to 50% the present value of the coupons and 20% the present value of the securitised maturity payment, which is ‘safe’.

The take-away for US credit-rating agencies is that they are naive to take the ‘No guarantees’ too literally. For if some Euro-government debt is risky then all is ultimately risky (inluding Bunds, because they are too big to save); and part of the point of the Single Currency is lower funding costs, which would be forfeit if Euro government bonds lose their ‘risk-free’ status and become virtual municipals.

Christ! Why don’t they just adopt Mosler’s plan (i.e. taxation-backed Greek issued bonds). It’s politically viable; it’s economically viable and it’s just plain sensible.

I’ve been spending the past week trying to plug it in the Irish media. The response: tepid. People are so locked into the dominant memes that they can barely even consider an alternative proposal.

The Eurozone will be be shipwrecked on the rocks of ignorance, stupidity and vapid thinking.

The Eurozone will be be shipwrecked on the rocks of ignorance, stupidity and vapid thinking. Philip Pilkington

Good! Individual countries should have their own money supplies. And if those countries were wise they would insure that their government money supplies were not de facto monopoly money supplies for private debts too.

Perhaps this is true. Personally, I don’t care either way as long as they’re allowed run structural deficits.

But the effects facing countries like Ireland of a Eurozone pullout are terrifying no matter what way you look at it. If the Eurozone project does indeed crash the pain will be felt disproportionately…

Personally, I don’t care either way as long as they’re allowed run structural deficits. Philip Pilkington

Agreed. Particularly if the private sector could escape any “stealth inflation tax” from too large a deficit.

But the effects facing countries like Ireland of a Eurozone pullout are terrifying no matter what way you look at it. If the Eurozone project does indeed crash the pain will be felt disproportionately… Philip Pilkington

Well, any debt to foreigners should be defaulted on and as for internal debt to banks, that could be revalued into the national currency (the Punt?) and equal bailout checks sent to every Irish citizen, including savers, till all the debt was paid off (The banks would have to be forbidden from leveraging the new money to preclude an inflationary spiral).

Ireland would end up with no external debt, no internal debt, happy savers, no inflation, no deflation and 100% reserve banking to make it much more difficult to drive the population into debt slavery.

I think the Punt would collapse and there might be an inflationary spiral. We’d also have to drastically change consumption habits as imports become expensive. I’d prefer not to go there.

I prefer Mosler’s plan, which is genius in its simplicity. It also reintroduces currency sovereignty through the backdoor and, I think, would be politically viable:

http://moslereconomics.com/2011/06/29/the-mosler-plan-for-greece/

Here’s my summary of the plan that I’ve been heckling newspaper editors with. It’s more accessible and it highlights the political aspects of it:

“So, here’s a basic run through of what the plan involves — I won’t go into too much detail, but if you have any questions about it I’ll be more than happy to answer them.

As you know, the Irish government is currently relying on the international markets for funding. The markets see Irish government bonds as extremely risky investments and this is driving up interest rates. Investors are worried that the Irish government might default on its debt which would wipe out an enormous amount of the bonds’ value (one of my friends gave a rough estimate of 80%). So, the markets are thus demanding very high rates of interest in order for them to hold the bonds (11-12% last time I checked). This, of course, is pushing the government ever closer to default as the interest payments compound upon the original payment.

So, what we need to do is convince the markets that Irish government bonds are a safe investment. Now, here’s the plan:

The Irish government issues new bonds. These bonds include a guarantee that if the Irish government defaults they will be usable in the payment of taxes to the Irish government. This guarantees that the bond will always retain its value — even in the worst case scenario of default. If the government did default investors could sell the bonds on to Irish banks and companies who could then use them to pay taxes. (They would also be an attractive holding for companies and banks who would have a safe investment that could be used for the payment in taxes in the event of a government default).

Of course, if the plan works the bonds are never used as tax payments because such a safe investment would not require high yields to attract investors. The Irish government would then be able to fund its debt at reasonable rates of interest. It would also have access to its own funds — so no external authority could demand austerity programs. And all this could be done without defaulting OR exiting the EMU.

Finally, I believe that this plan would be politically as well as economically viable. EU politicians would be relieved of their burden; their constituents would see this as Ireland ‘paying its own way’ which would massively ease tensions in the EU. Irish politicians would find it attractive because they’d regain full fiscal sovereignty. The Irish people would find it attractive because… well… protestors in Greece tried to set fire to the finance ministry the other day — need I say more?”

Mosler’s plan sounds reasonable. After all, it is taxation that backs up a government’s money. So those tax-bonds would essentially become an interest paying government money supply.

But Ireland really needs to allow genuine capitalism too by abolishing the banks’ monopoly on private money creation. That would be a win-win for the private sector and the government since it should eliminate the destructive boom-bust cycle.

Well, you know my feelings on that: namely, that central bank destruction would greatly exacerbate the boom-bust cycle. In my mind that isn’t even open to question. The land of banking is ‘Wild West’ enough as it is; more cowboy capitalism is the last thing that’s needed.

Well, you know my feelings on that: namely, that central bank destruction would greatly exacerbate the boom-bust cycle. Philip P

Actually, it is usury itself that is responsible for the boom-bust cycle since the debt normally compounds faster than the real economy. A lender of last resort makes it much worse however since it allows much greater leverage before the inevitable crash.

One way to abolish usury would be to require that bank money be the common stock of each bank. Rather than collect interest on their deposits, depositors would receive capital gains (or losses).

… and there might be an inflationary spiral. Philip P

I don’t see how. Banks are the source of temporary money (credit) and national governments are the source of base money. If the Irish banks were forbidden to create any more credit and the Irish government reverted to the Punt then the Irish government would be the sole source of new money into the Irish economy.

Useful article, I think I understood the basic idea behind the French plan except for one detail. What I got is that, since the “new bonds” will have a zero-coupon part that covers the principal, Greece will be paying interest for thirty years but will not have to pay any principal at the end of the thirty years. Is that correct? (If it is not, they the deal is too good for the banks and I do not see how this constitutes participation of the private sector in carrying the load.)

Ya, ok. So we’ve got our alternate plans involving somethin’ to do with Kings, Crowns and Punts (terrible name for money – peso would be better) and the ultimate plan to pay gov employees and contractors in defaulted bonds (F. Beard’s secret plan). I assume Phil will be employed in the private sector and putting all his savings in US Treasuries.

So I got all that. But I’m still wondering if anyone has firmed up the rules and definition of a “credit event” so we know yet if the current plan triggers one, and if anyone knows yet who is the International Official in charge of declaring one and will anyone listen to this person when it comes time to pay on all that CDS? (30% of Greek Debt)